1 Introduction

Amprino 〚1〛 was the first to see the diverse bone typologies as the expression of differential growth rates. Since then, some preliminary studies 〚2–4〛 have given the first quantitative values for this relationship, called ‘Amprino’s rule’ 〚2〛. Our study, conducted on comprehensive growth series and based for the first time on statistical methods, aims at (1) measuring and testing the validity of the rule (i.e. the differential growth rates of the diverse bone tissue types) and (2) clarifying the rule by testing its relevance to various typological characters.

Background: primary periosteal bone tissues

The bone tissues classification used here is the one established by Ricqlès 〚5, 6〛, internationally accepted and used. Among primary periosteal bone tissues (our study’s interest), Ricqlès describes four major types possibly deposited during post-natal growth (Fig. 1):

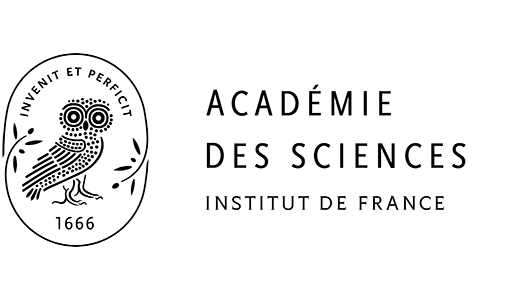

The four periosteal compact bone types of Ricqlès' classification, as seen in the mallard's long bones. Undecalcified cross-sections of diaphyseal level, polarised light (a to d) or natural light (e). a. ‘Lamellar (or parallel-fibered, as seen here) non vascular bone’ (LNV). Humerus of a 407 days old mallard. b. ‘Lamellar (or parallel-fibered) bone with simple vascular canals’ (LSV). Same bone as a. c. ‘Lamellar (or parallel-fibered) bone with primary osteons’ (LPO). Tibiotarsus, 407 days old. Primary osteons are separated by parallel-fibered matrix, which is prevalent over osteonal matrix. On this view, one can also see the external and internal ‘fundamental systems’ (both constituted of anosteonal bone), typical of mature diaphysis. d. ‘Fibro-lamellar complex’ (FLC). Tibiotarsus, 37 days old. Primary osteons, bigger than in LPO type, are almost contiguous. Thus, osteonal matrix is prevalent over the woven matrix present between osteons. e. Growing FLC in a 37 days old mallard's radius, showing peripheral woven network, progressively filled with osteonal deposit. Scalebar is 200 μm for a and b, 400 μm for c, d and e.

- • (1) lamellar (or parallel-fibered) non vascular bone (LNV);

- • (2) lamellar (or parallel-fibered) bone with simple vascular canals (LSV);

- • (3) lamellar (or parallel-fibered) bone with primary osteons (LPO);

- • (4) woven bone with primary osteons, also called ‘fibro-lamellar complex’ (FLC).

Among tissues with primary osteons (LPO and FLC types), several osteonal orientations can be distinguished, as for example (Fig. 2):

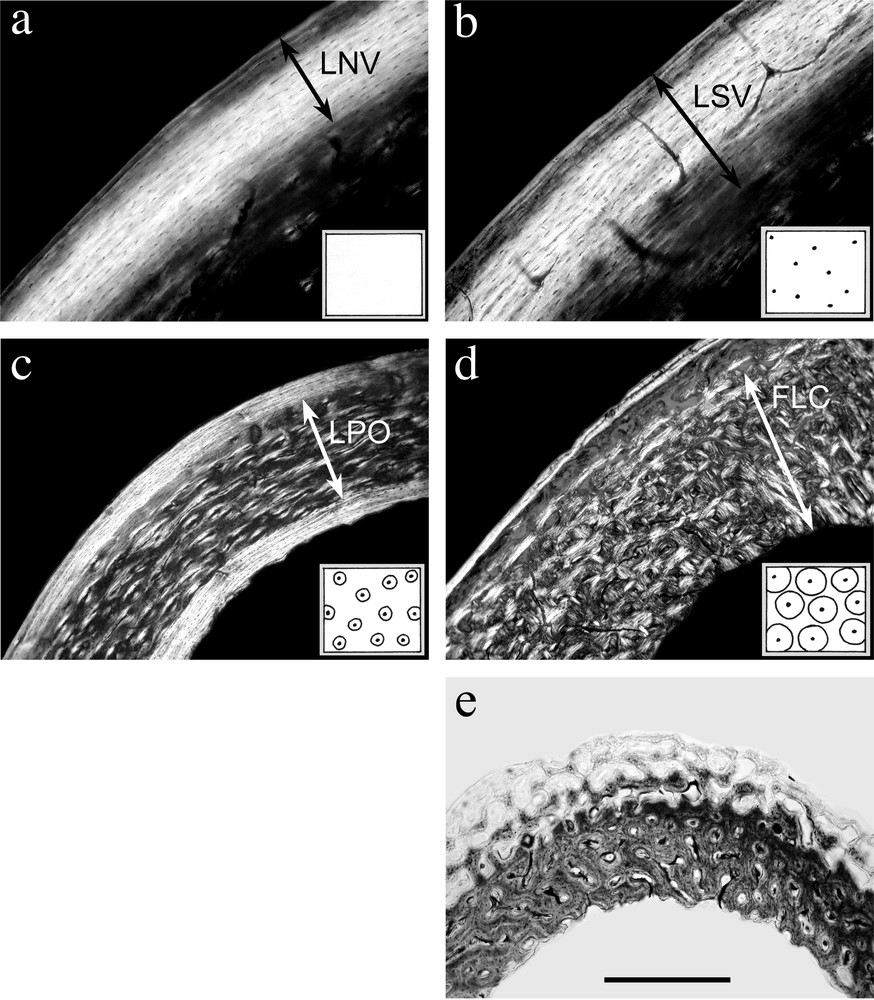

The three osteonal orientations frequently seen in the mallard's long bones. Undecalcified cross-sections of diaphyseal level, natural light. a. Majority of longitudinal osteons (L). Radius, 407 days old. b. Majority of longitudinal and circular osteons (LC): ‘laminar bone’. Ulna, 175 days old. c. Oblique and curved osteons, organised in an irregular network (I): ‘reticular bone’. Femur, 30 days old. Scalebar is 400 μm.

- • (1) longitudinal (L) primary osteons;

- • (2) longitudinal and circular (LC) primary osteons (fibro-lamellar complex (FLC) showing this orientation is called ‘laminar bone’; lamellar bone with primary osteons (LPO) showing this orientation is called ‘pseudo-laminar bone’);

- • (3) oblique primary osteons, organised in an irregular (I) network (fibro-lamellar complex (FLC) showing this orientation is called ‘reticular bone’).

Other osteonal orientations, rarely observed in the mallard, are not described here.

All of these categories, of first (LNV/LSV/LPO/FLC) or second (L/LC/I) level, correspond to artificial fractions of a typological continuum: all possible intermediaries are observable 〚5, 6〛. Nevertheless, this classification appeared quite operational for testing Amprino’s rule.

2 Materials and methods

Periosteal growth rates were measured in humeri, radii, ulnae, femora, tibiotarsi and tarsometatarsi of 17 mallards aged from 16 to 175 days after hatchling, reared in boxes (individuals aged from 16 to 51 days) or in a 250 m2 aviary (other individuals). Each mallard received two, three or four intraperitoneal injections of fluorochromes (fluorescein, alizarin, tetracyclin or xylenol-orange), at time intervals of one to four weeks.

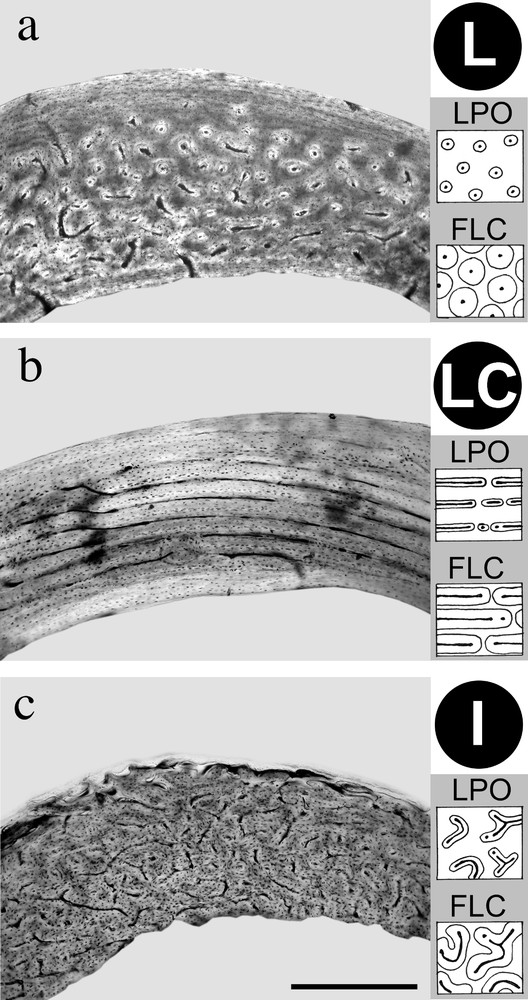

For each analysed diaphysis, measures were done for each time interval delimited by isochronous lines (fluorescent labels and periosteal surface), in four orthogonal directions, in order to consider rate discrepancies linked to osseous drift. For each growth rate measure (under ultraviolet light), associated bone typology was determined (under natural and polarised light), on an 800-μm width (Fig. 3). Major bone type identification criterions were as follows:

Fluorescent labels and growth rate measures. Undecalcified cross-sections of diaphyseal level, ultraviolet light. a. Typical labels in anosteonal bone (LSV or LNV types). Ulna of a 103 days old mallard, labelled with fluorescein at 89 days. Though peripheral label affects periosteal bone, medullar label concerns endosteal bone deposited at the same time but centripetally. b. Multiple labels in a 97 days old radius. First fluorescein injection at 40 days, alizarin injection at 47 days, xylenol-orange injection at 68 days and second fluorescein injection at 83 days. The last two labels in periosteal bone (most peripheral ones) are typical of LPO type: primary osteons are clearly isolated in prevalent extra-osteonal matrix. c. Typical labels in FLC, seen in a 30 days old tibiotarsus. Fluorescein injection at 9 days, xylenol-orange injection at 16 days. Primary osteons are bigger than in LPO (comparison should be made between the most peripheral closed labels) and almost contiguous. Osteonal matrix is prevalent over extra-osteonal woven matrix. d. Measures of growth rates. Example of a double-labelled cortex, without endosteal bone. Each double-ended arrow represents a measure of distance between isochronous lines, converted into periosteal growth rate when divided by the time elapsed between the two boundaries. For each growth rate measure, associated typology was determined on an approximately 800 μm width (greyed out area). PS: periosteal surface. PMS: perimedullar surface (diachronous, resulting from centrifugal bone resorption). L1: first fluorescent label. L2: second fluorescent label. Scalebar is 400 μm for a, b and c.

- • (1) more than one vascular canal in the studied area: vascularised tissue, belonging to LSV, LPO or FLC type;

- • (2) vascular canals encircled by concentric matrix deposit: osteonal tissue, belonging to LPO or FLC type;

- • (3) osteons radially separated by an interval inferior to osteonal diameter: tissue composed of consequential (or even prevalent) osteonal matrix, belonging to FLC type.

These three simple criterions succeed in distributing all observed bone tissues among the four major types described by Ricqlès. Other criterions can be used, especially based on matrix types 〚5, 6〛, but appeared to be less operational than these.

Moreover, prevalent osteonal orientations were noted for each observation (when they were explicit enough).

Finally, in the case of FLC or LPO tissue types, osteon diameter was measured, in the direction of the diaphyseal radius.

Some measures were not feasible, for several possible reasons:

- • more than one bone type present in the studied area, preventing from any unique associated typology determination;

- • discontinuity of deposit, disabling growth rate measure;

- • massive osseous drift, causing arrested growth or even resorption on one side of the diaphysis;

- • unexpected extra-diaphyseal section level; diametral growth modalities in metaphysis being quite complex 〚7〛, measures at those levels were irrelevant for our study.

Despite these restrictions, a total of 288 measures of the local periosteal growth rate could be made, distributed in the growth series. An associated bone typology corresponds to each one of these measures.

Moreover, 57 extra measures were made in endosteal bone (centripetally deposited on the perimedullar surface, from the third post-natal month), in order to compare its growth rate with periosteal bone.

According to normality tests (Lilliefors’ and Shapiro-Wilk’s), growth rate variable does not show normal distribution for the various typological categories. This is expected when one knows that those categories are artificial fractions of a typological continuum. Hence, analysis used non-parametric statistics, possibly less powerful than classical parametric statistics, but distribution-free. Categories were first compared globally by Kruskal-Wallis’ ANOVA. When this test returned significant heterogeneity, categories were compared by the Mann-Whitney 2 sample test (completed by distribution-sensible tests for the study of endosteal bone: see chapter 3.4). Relationship between osteon diameter and tissue growth rate was evaluated by Spearman’s correlation test.

3 Results

3.1 Major periosteal bone types and growth rate

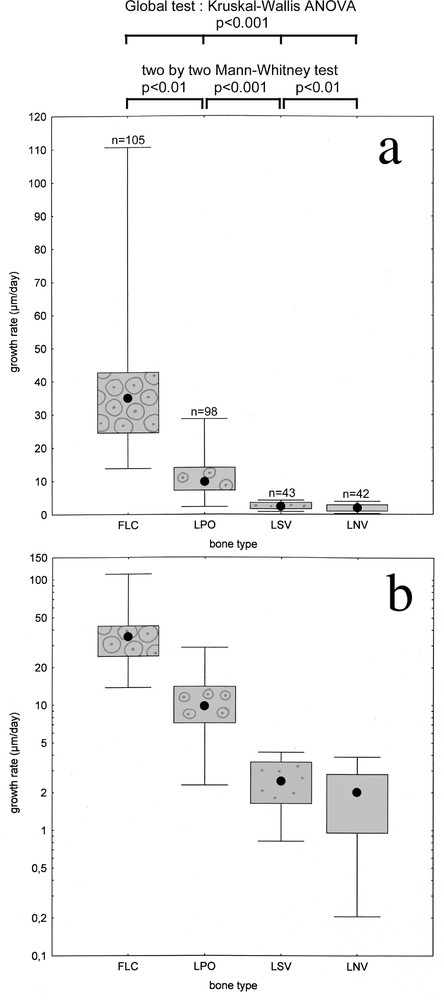

Statistical analyses (top of Fig. 4) show significant discrepancies between the four major bone types (FLC, LPO, LSV and LNV). Error probability associated with dissimilar growth rate assertion is less than 1:100 when one compares FLC and LPO, less than 1:1000 between LPO and LSV and less than 1:100 between LSV and LNV. Note that these significant discrepancies concern first level of typological classification, without any allusion to primary osteons orientation.

Major periosteal bone types and growth rate. a. Growth rate median value (black dot), quartile (box) and total range (whiskers) for each of the four types. b. Same graph, with logarithmic vertical scale.

According to graphs, transition from FLC to LPO happens for approximately 20 μm/day growth rate, and transition from LPO to LSV is seen around 5 μm/day. Distinction between LSV and LNV is less obvious: overlapping of the two growth rate ranges is important, affecting the quartiles (i.e. the ‘middle’ half of measures, symbolised by greyed-out boxes).

3.2 Primary osteons diameter and periosteal growth rate

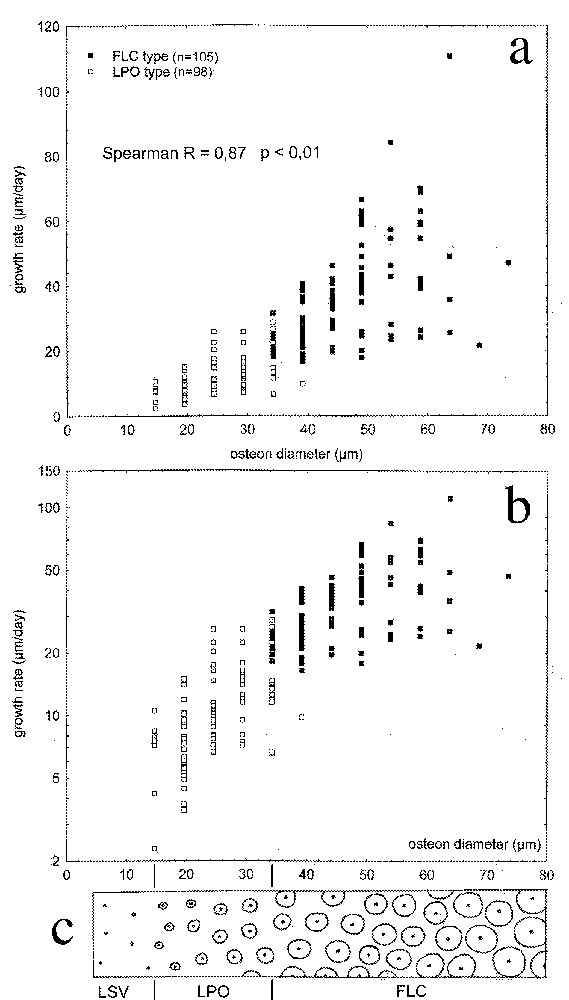

Correlation between primary osteons diameter and tissue growth rate is presented in Fig. 5. Vertical dispersal can be partially attributed to the imprecision of osteon diameter measurement (primary osteons boundaries are often hard to locate precisely). However, correlation is significant, according to statistical test. The bigger the incorporated cavities by the deposited tissue, the faster its growth.

Primary osteon diameter and periosteal bone growth rate. a. Scatterplot. The pattern of horizontal repartition corresponds to discrete measure with the optical micrometer. The non-parametric correlation coefficient is high, the correlation is significant. b. Scatterplot with logarithmic vertical scale. c. Outlined associated typology. Osteon become prevalent for a diameter of approximately 35 μm, corresponding to a periosteal growth rate around 20 μm/day. Smallest primary osteons were 15 μm in diameter. Beneath this value, only simple vascular canals were present, approximately 10 μm in diameter. Constant vascular density presented here is only an approximate starting point (see text).

Again, this correlation is obtained without allusion to osteonal orientation.

Osteon diameter is an indirect estimation of the osteonal fraction of the tissue, bigger osteons being closer to each other. In the studied bones, transition from prevalent extra-osteonal matrix (LPO type) to prevalent osteons (FLC type) happens for osteons approximately 35 μm in diameter.

Note that if this correlation holds for osteonal fraction (indicated by osteonal diameter), it does not necessarily apply to vascular density. The relationship between osteonal fraction of the tissue and the density of vascular canals (number of canals per unit surface), still to be studied, is perhaps not monotonal. Thus, vascular density alone, as easily seen in natural light, might not be the best indicator of tissue growth rate, inside osteonal tissues. Further investigations shall be concerned with this issue.

3.3 Osteonal orientation and periosteal bone growth rate

Three remarkable orientations of primary osteons were frequently observed in our material:

- • ‘longitudinal’ orientation: primary osteons mainly longitudinal (L);

- • ‘laminar’ orientation: primary osteons mainly longitudinal and circular (LC) (as it can be seen on a cross-section, bidimensionally; real tridimensional organisation of ‘laminar bone’ is more complex: see for example blueprints in 〚8〛);

- • ‘reticular’ orientation: primary osteons mainly oblique, curved and anastomosed, forming an irregular network (I).

Those three orientations were equally observed in tissues with osteonal prevalence (FLC) and in tissues with prevalent extra-osteonal matrix (LPO).

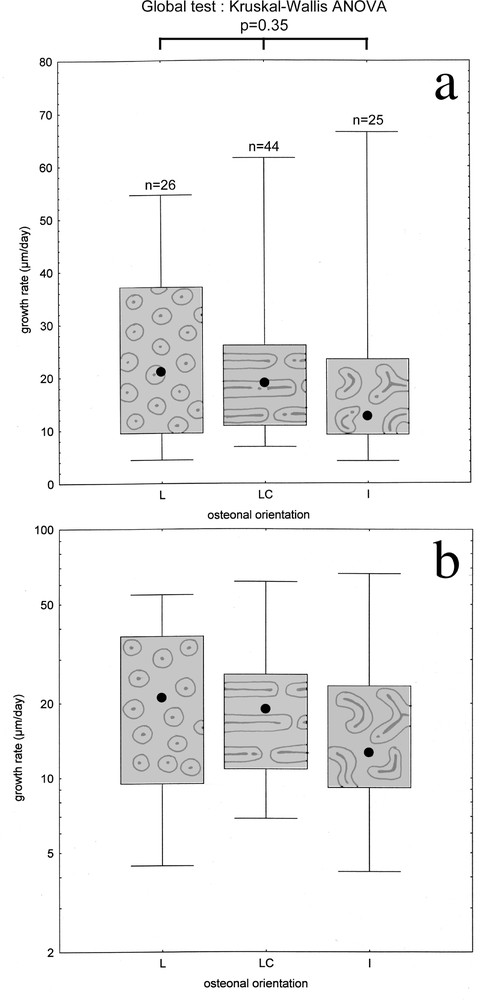

As Fig. 6 shows, no significant growth rate heterogeneity could be detected between the three orientations: Kruskal-Wallis’ ANOVA returns error probability of 35% when performed inside the FLC + LPO group. Even larger error probabilities are obtained when testing inside each one of the two typologies.

Osteonal orientation and periosteal bone growth rate. a. Growth rate median value (black dot), quartile (box) and total range (whiskers) for each of the three remarkable orientations frequently encountered in the mallard's long bones. b. Same graph, with logarithmic vertical scale.

3.4 Endosteal bone

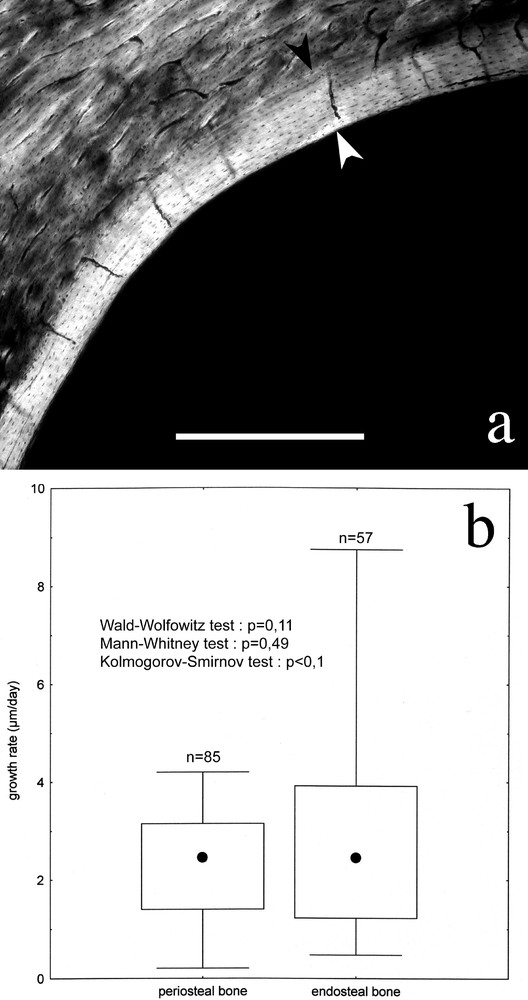

Concerning typology, endosteal bone is generally osteon-free, as could be seen in our 57 punctual observations. It is lamellar with simple vascular canals (usually radial, or sometimes irregular), or avascular. This bone, forming the ‘internal fundamental system’, is typologically similar (at the histological level) to periosteal bone of the LSV and LNV types, constituting the ‘external fundamental system’ (for a typical view of adult cortex with its two ‘fundamental systems’, see Fig. 1c).

Concerning growth rate, when the 57 endosteal measures are compared to the 85 periosteal anosteonal bone measures (LSV and LNV types), some discrepancies appear. Fig. 7 shows that endosteal bone can be deposited at rates of almost 9 μm/day, twofold maximal rates found in periosteal anosteonal bone. Despite this fact, medians of rate values are similar, preventing statistical tests from detecting significant discrepancies between the two categories (however, Wald–Wolfowitz and Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests, sensitive to differences in the rates distributions, return a p value close to 1/10, almost significant).

Endosteal bone. a. Typical endosteal bone (between arrows), as seen in a mallard diaphysis. Bone is of the LSV type, with radial simple vascular canals. Irregular vascular canals and non vascular (LNV) bone were observed, too. b. Growth rate median value (black dot), quartile (box) and total range (whiskers) for endosteal bone, compared to anosteonal periosteal bone (LSV and LNV).

4 Discussion

Our results show clearly that some typological characters of periosteal compact bone tissue are narrowly linked to its growth rate, while others are not, or weakly and probably more indirectly.

On the one hand, it appears that the incorporation of cavities (upcoming primary osteons) in the tissue at the time of its deposit, and the proportion of theses cavities, are determinant parameters of the tissue’s growth rate. This agrees with previous observations 〚1, 3, 4, 6, 9〛, which described fibro-lamellar complex as the major bone type with the fastest deposit rate, while non vascular lamellar bone was shown to be the most slowly deposited type. Concerning this point, our study gives a quantitative and statistical confirmation of Amprino’s rule, as it was already understood. Further investigations may focus on the functional link between osteonal fraction and growth rate: does bone initial porosity have only volumetric consequences on bone growth?

On the other hand, the orientation of incorporated cavities and of consecutive primary osteons seem to be characters with relative independence regarding growth rate, at least for the three vascular orientations observed in this study. This result was already suggested by discrepancies in the findings of previous studies 〚3, 4, 9〛, which failed in differentiating laminar and reticular bone growth rates, and emphasised the overlap of growth rates between them. Our findings suggest that Amprino’s rule does not concern osteonal orientation in a narrow sense. However, it remains that the highest rates at which diverse FLC tissues can be laid down are still unknown and that they may not overlap at these rates, as suggested by extreme values in Fig. 6 and by general comparative data 〚6〛. On the other hand, osteonal orientations might rather be linked to biomechanical or other factors. Further investigations shall be concerned with such issues.

Last, discrepancies found in the same bone between maximal growth rates of endosteal and periosteal anosteonal tissues suggest that absolute deposition rates might also be affected by some unexpected topological factors, still to be explained. This points to the multiple sources of variation affecting absolute bone growth rates, which should be kept in mind when attempting transposition of those rates, notably to fossil species 〚4, 10, 11〛.

5 Conclusion

According to our results, Amprino’s rule applies closely to the presence and the proportion of primary osteons in periosteal compact bone tissues, characters depending on the first level of Ricqlès’ typological classification 〚5, 6〛. Tissues deposited with cavities for primary osteons grow faster. The bigger the cavities, the faster the growth.

On the other hand, for our 288 observations in the mallard, the same rule does not apply to the second level of the classification, concerning osteonal orientation. Hence, osteonal orientations would be good candidates for biomechanical functions, rather than solely ontogenetic ones (i.e. directly related to growth rates).

Version abrégée

Amprino a montré en 1947, pour la première fois, que les variations structurales du tissu osseux périostique primaire (constituant notamment le tube diaphysaire des os longs) sont l’expression de vitesses différentielles de croissance. Cette relation structuro-fonctionnelle fondamentale, appelée « règle d’Amprino », a été depuis observée chez diverses espèces de tétrapodes. La présente étude, réalisée chez le canard colvert (Anas platyrhynchos), a pour objectif d’apporter des preuves quantitatives, testées statistiquement, à l’appui de la règle d’Amprino et de préciser sa valeur pour divers caractères microstructuraux.

Nous avons observé l’histologie diaphysaire des principaux os longs (humérus, radius, ulna, fémur, tibiotarse et tarsométatarse) de 17 individus, âgés de 16 à 175 jours après éclosion, élevés en cage et en volière. La classification typologique de Ricqlès nous a permis de regrouper les différents tissus osseux observés en quatre catégories majeures : (1) tissus lamellaires (ou à fibres parallèles) avasculaires, (2) tissus lamellaires (ou à fibres parallèles) vasculaires (canaux vasculaires simples), (3) tissus lamellaires (ou à fibres parallèles) à ostéones primaires, et enfin (4) complexes fibro-lamellaires (ostéones primaires situés dans une matrice à fibres enchevêtrées). Lorsque des ostéones primaires étaient présents (cas 3 et 4), leur orientation a été notée, ce qui a permis de caractériser des tissus laminaires, réticulaires et à ostéones longitudinaux. Le diamètre des ostéones a été mesuré.

À l’aide de marquages fluorescents multiples réalisés au cours de la croissance des mêmes individus (injections intrapéritonéales de fluorescéine, alizarine, tétracycline et xylénol–orange, à des intervalles de une à quatre semaines), nous avons d’autre part pu mesurer les vitesses d’ostéogenèse périostique des différents os longs en croissance.

En associant à chaque mesure de vitesse d’ostéogenèse (288 au total) la typologie osseuse observée et ses caractères microstructuraux associés, nous avons pu tester la règle d’Amprino par des méthodes statistiques (tests non paramétriques). Les résultats sont les suivants.

- • (1) Les quatre grandes catégories de tissus ont des vitesses d’ostéogenèse significativement différentes ; les complexes fibro-lamellaires se déposent à des vitesses élevées, de 20 à 100 μm par jour. Les tissus lamellaires à ostéones primaires se déposent à des vitesses intermédiaires, de 5 à 20 μm par jour. Les tissus lamellaires sans ostéones primaires (i.e. à canaux vasculaires simples ou avasculaires) se déposent à des vitesses inférieures à 5 μm par jour. À l’intérieur de ce type « anostéonal », il apparaît que les tissus avasculaires ont les vitesses de dépôt les plus faibles.

- • (2) Lorsque les ostéones primaires sont présents (tissus lamellaires à ostéones primaires et complexes fibro-lamellaires), c’est-à-dire lorsque la vitesse d’ostéogenèse est comprise entre 5 et 100 μm par jour, la vitesse d’ostéogenèse du tissu est positivement et significativement corrélée au diamètre des ostéones primaires qu’il contient. Cela indique que plus les ostéones primaires occupent une part importante du tissu osseux (c’est-à-dire plus le tissu a été initialement déposé sous forme lacunaire), plus la vitesse de dépôt est élevée.

- • (3) L’orientation des ostéones primaires et les typologies qui s’y rattachent ne semblent pas être concernées par la règle d’Amprino : aucune différence significative de vitesse d’ostéogenèse n’a pu être détectée entre les tissus laminaires, réticulaires et à ostéones longitudinaux.

- • (4) Enfin, 57 mesures complémentaires des vitesses d’ostéogenèse de l’os endostéal permettent de mettre en évidence une hétérogénéité intéressante : les tissus endostéaux, malgré leur structure lamellaire sans ostéones primaires, sont capables de se déposer à des vitesses supérieures à 5 μm par jour (jusqu’à environ 9 μm par jour dans notre échantillon). Cette différence entre tissus périostiques et endostéaux montre que la règle d’Amprino est probablement sous la dépendance de facteurs topologiques encore méconnus à ce jour. Ainsi, toute transposition des vitesses absolues d’ostéogenèse (notamment aux espèces fossiles) doit être faite avec prudence.

En conclusion, cette étude a permis de vérifier quantitativement et de préciser la règle d’Amprino chez une espèce présentant une importante histodiversité osseuse. Plus concrètement, on peut désormais affirmer, en accord avec les résultats de précédentes études, que la présence et la proportion des ostéones primaires dans l’os périostique sont des caractères histologiques clairement liés à la vitesse d’ostéogenèse. En revanche, il apparaît que la règle d’Amprino ne peut expliquer l’ensemble de l’histodiversité osseuse observée. En effet, l’orientation des ostéones primaires dans les tissus à dépôts rapides ne semble pas liée aux variations de vitesse d’ostéogenèse. Nous formulons l’hypothèse que les contraintes biomécaniques jouent un rôle important dans le déterminisme de l’orientation des ostéones primaires.