1 Introduction

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) was first diagnosed in England in late 1986 〚1〛, though in retrospect it has been recognized that a clinically affected animal examined in 1985 was suffering from BSE 〚2〛. In Great Britain the disease was made notifiable and the ban on the use of ruminant protein in the production of ruminant feed came into force in 1988 〚3〛.

Although this ban dramatically reduced the incidence of infections, it was not completely effective 〚4〛. Due to the long incubation period of BSE (five years on average 〚4, 5〛), the impact of such interventions on disease incidence does not become evident for some years. Thus, the annual incidence of clinical cases in Great Britain peaked in 1992, with more than 178 000 confirmed clinical cases identified through passive surveillance to date.

Smaller epidemics have occurred elsewhere in Europe, with Northern Ireland, Switzerland, the Republic of Ireland, Portugal and France reporting hundreds of clinical cases. Other countries both within the European Union (EU) and more widely (Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain) have reported small numbers of clinical cases.

In addition to clinical cases, active surveillance (all EU cattle over 30 months of age slaughtered for consumption must be tested for BSE) has identified positives among apparently healthy animals (subject to normal slaughter) in many European countries (Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, the Republic of Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain and Portugal) 〚6〛.

Although the tests are not yet sufficiently sensitive to detect all infected animals 〚7, 8〛, there are no age restrictions placed on the consumption of animals tested negative due to the relatively low incidence of BSE infection outside the United Kingdom. Within the United Kingdom the risk of human exposure to potentially infectious beef and beef products has been considerably reduced by the restriction that only cattle under 30 months of age are slaughtered for consumption. These younger cattle are both least likely to have been infected, and for the few that may have been infected, they are most likely not in the late stage of the pre-clinical disease.

Epidemiological analyses of the BSE epidemics in the United Kingdom and other affected countries have produced estimates of the past exposure of consumers to potentially infectious beef and beef products from cattle infected with the aetiological agent of BSE, believed to be an abnormal form of the prion protein, and slaughtered prior to clinical onset. Backcalculation analyses of BSE clinical incidence data have revealed that, due to the long average incubation period of BSE compared to the average lifetime of cattle, the majority of infected cattle were slaughtered for consumption before they experience the onset of clinical signs of disease 〚4, 5, 9–10〛. For example, it has been estimated that some 900 000 cattle were infected over the course of the epidemic in Great Britain 〚4, 5〛, with an additional 10 000 infected in Northern Ireland 〚11〛. The backcalculation models have also provided predictions of future BSE clinical incidence shown to be highly accurate when compared with subsequently observed data 〚12〛.

In 1989 scientists anticipated the possibility of BSE in French cattle 〚13〛 suggesting that such cases could result from infections due the consumption of imported British meat and bonemeal between June 1988 (when it was banned from use in British ruminant feed) and August 1989. Due to the long incubation period of the disease, it was predicted that such cases would arise from 1991 〚13〛. The French epidemiological surveillance network on BSE was established in December 1990 (for details see 〚14〛) and soon thereafter (February 1991) the first case of French BSE was identified 〚15〛.

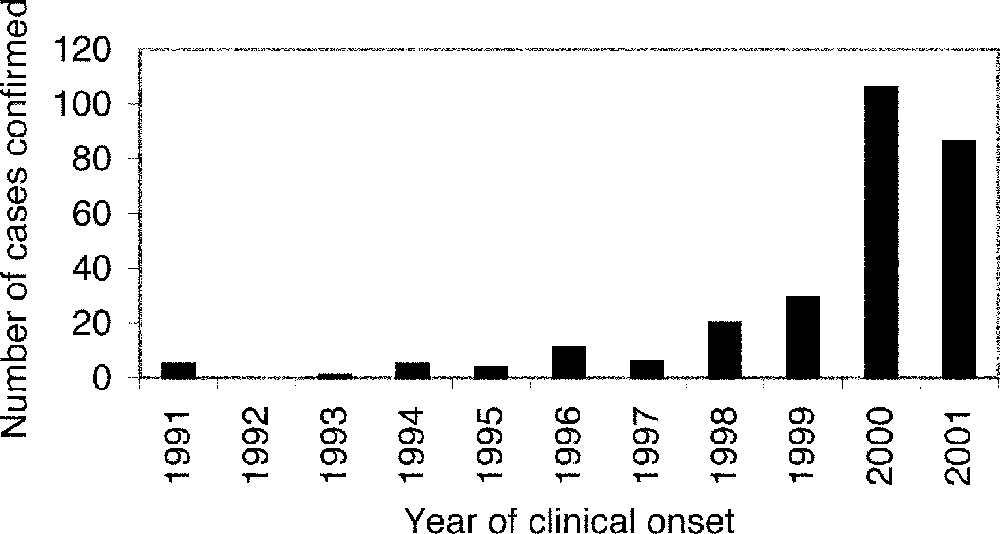

It was not until 2000 that widespread public attention became focussed on BSE in France, when the incidence of confirmed clinical cases was observed to be increasing (Fig. 1) 〚16–18〛. At the same time, clinical incidence in the British, Irish, Swiss and Portuguese epidemics was declining. Epidemiological analysis of the BSE epidemic in France (based on clinical cases confirmed and reported by 17 November 2000) indicated that at least 1200 French cattle had been infected since mid-1987 〚19〛.

Observed annual incidence of reported clinical cases in native-born French cattle by year of clinical onset (determined by the recorded date of suspicion).

This extended epidemiological analysis reassesses the French BSE epidemic based the additional year of clinical case data now available, providing predictions of future cases and assessing the sensitivity of the results to assumptions regarding underreporting and the survival distribution of French cattle. Results of the pilot study in northwestern France (Brittany, Normandy and Pays de la Loire) from 15 000 cattle are also analysed. Implications of the results for the future incidence of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (vCJD) in France are discussed.

2 Methods

Time-varying trends in infection incidence and underreporting cannot be disentangled by analysis of the cohort incidence rates alone, but requires careful analysis of the observed age- and cohort-specific incidence 〚4, 5, 9–10〛. Due to the relatively low number of clinical cases of BSE in France, a simplified backcalculation analysis is performed incorporating age-dependent susceptibility/exposure to infection and the incubation period distribution in an age-at-onset distribution 〚20〛. The time-varying risk of feed-borne infection is estimated as a cohort-specific infection incidence, where the annual birth cohort defined, as in earlier work, such that the 1989 cohort consists of cattle born between 1 July 1988 and 30 June 1989. Between-cohort differences in the underlying age-at-onset distributions arise are assumed to arise due to underreporting.

Thus, the expected age- and cohort-specific incidence of reported BSE cases, denoted μ(c,a) for age at clinical onset a years and birth cohort c, is given by:

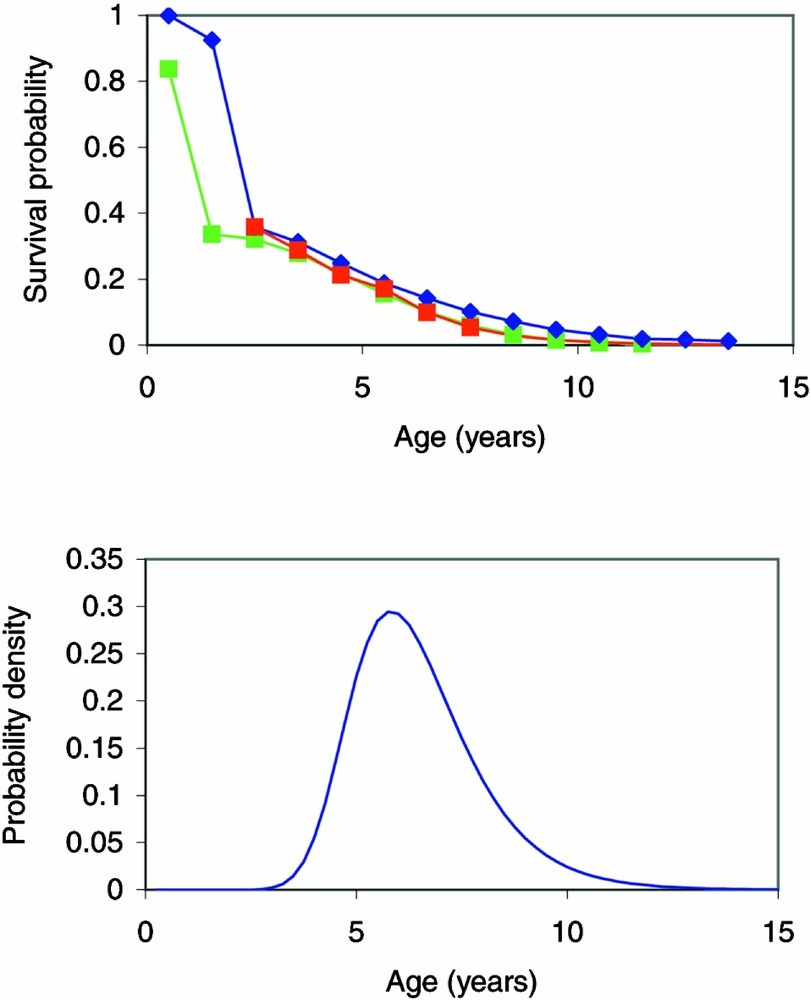

The survival distribution for Great Britain (Fig. 2a) was estimated from data on the lactation distribution of a subset of British dairy herds in 1982, 1988, 1989, 1991 and 1994 〚4, 9, 21〛. The lactations were transformed into ages using data on calving intervals and average age at first lactation. Alternative survival distributions, estimated independently from data on Portuguese and French cattle 〚20, 22〛, suggest that mainland European cattle have shorter average lifetimes (Fig. 2a). The data on French cattle were obtained from a study on the longevity (over the first six lactations) of French Friesian and Montbéliarde dairy cows 〚22〛. Survival to 2.5 years was assumed to equal that in British cattle, and survival beyond the sixth lactation was assumed to be exponential. Reduced survival probabilities increase the estimated number of infected animals required to give rise to the observed number of cases.

(a) Survival distributions estimated from British 〚4, 9, 21〛 (blue), French 〚22〛 (red) and Portuguese 〚20〛 (green) cattle. (b) The age-at-onset distribution estimated from the convolution of the age-dependent exposure/susceptibility function and the incubation period distribution, using validated parameter estimates obtained from the best-fit backcalculation model of the BSE epidemic in Great Britain 〚5〛.

The age-at-onset distribution, f(a), is approximated by the convolution of the age-dependent exposure/susceptibility function and the incubation period distribution, using validated parameter estimates obtained from the best-fit backcalculation model of the BSE epidemic in Great Britain, Model C7 in 〚5〛 (Fig. 2b).

A number of parametric forms were examined for the time-dependent underreporting function, where is the probability that a clinical case onset in year t is reported. We report results from a constant underreporting model (where for t < T and for t ≥ T) and a logistic model (where

As noted in the discussion of earlier backcalculation analyses 〚5〛, it is impossible to fit a time-dependent probability of reporting across the whole epidemic in the absence of independent data on reporting rates. Thus, the earlier analysis 〚19〛 assumed complete reporting in 2000. Utilising an additional year’s data the current analysis is able to examine the validity of this assumption by allowing for underreporting in 2000, but assumes complete reporting in 2001.

A transformation of the time-dependent reporting probabilities into cohort-age-dependent reporting probabilities is required since animals in birth cohort c may experience clinical onset at age a in years c + a – 1, c + a, and c + a + 1. Thus,

Annual incidence fitted values and predictions were obtained converting from cohort-age cross-classification to year of onset such that

Parameters reflecting cohort incidence, φ(c), and underreporting were estimated by maximising the data likelihood, assuming that clinical incidence data arose from a Poisson distribution 〚19〛. Hypothesis tests were performed comparing twice the difference in the data likelihood values under different models with the appropriate chi-squared distribution.

The analysis of data from testing of pre-clinical animals requires adjustment for the proportion of infected animals still alive by the age at which the animal was tested and the sensitivity of the test as a function of the animal’s incubation period. Thus, if the detected preclinical prevalence in a group of animals in cohort c tested at age a is pD(c,a), then the best estimate of the overall prevalence of infection, pI(c), in that cohort is given by:

3 Data

Details on individual BSE cases are available on the Internet from the ‘Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des aliments’ (AFSSA, the French agency for food safety) and the ‘Ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche’ (the French ministry of agriculture and fishing). (Details of the first 24 confirmed cases were published in 1996 〚23〛.) Linking these sources of information, it is possible to obtain the date of suspicion, date of declaration, month and year of birth, and administrative district (‘département’), for each animal confirmed with BSE. The year and age at clinical onset are both determined on the basis of the recorded date of suspicion (rather than the date of confirmation which includes non-disease-related delays).

By 8 January 2002, 274 confirmed cases had been reported (including one case in an animal imported from Switzerland). The annual incidence of reported clinical cases in native-born French cattle (Fig. 1) tripled between 1999 and 2000 but appears to have been similar in 2000 and 2001. The 2001 annual incidence was not complete at the time of analysis because cases are classified by the date of suspicion but are not included in the database until the case is confirmed/declared. This reporting delay is variable, but a typical delay is a few weeks.

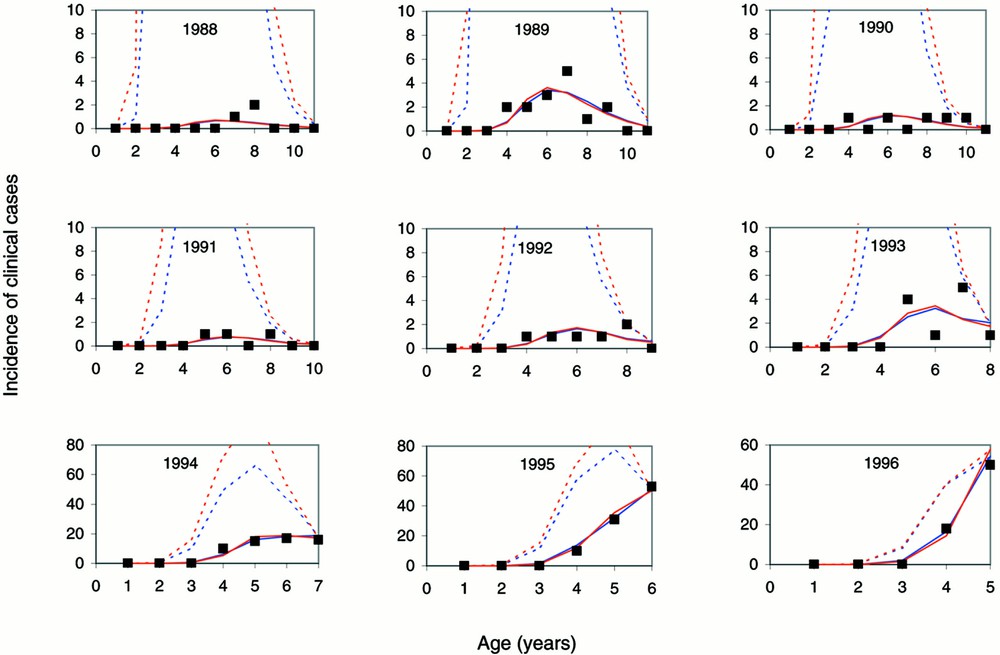

The data were cross-classified by birth cohort and age at the clinical onset of BSE (Fig. 3). A correction (6% increase) was made to the incompletely observed incidence cells, μ(c, a), where c + a = 2001 (for example, the incidence at age 5 in birth cohort 1996), to adjust for reporting delay and any remaining incidence which might occur up to 29 June 2002 (for example, an animal born on 20 June 1996 might experience clinical signs and be identified as a BSE suspect on 15 June 2002 while still 5 years of age). Incidence in the oldest possible incidence cells, including for example the seven cases in age 6 animals in birth cohort 1996 confirmed by 8 January 2002, were not analysed because these data are as yet too incomplete. Furthermore, the analysis is restricted to cattle born since mid-1987 (the ten birth cohorts 1988 to 1997); only six clinical cases arose from French animals born prior to this date.

Observed (■) and fitted age-specific reported clinical case incidence in French-born cattle by birth cohort, using the survival distributions estimated from British (blue) and French (red) data assuming a logistic underreporting model. The dotted lines represent the expected age-specific incidence, had cases been fully reported throughout the epidemic. There was only a single confirmed case (at age 4) in the 1997 birth cohort (not presented graphically).

Regional analyses are also conducted dividing France into four regions: Brittany (districts: 22 Côtes-d’Armor; 29 Finistère; 35 Ille-et-Vilaine; 56 Morbihan); Normandy (districts: 14 Calvados ; 50 Manche; 61 Orne); Pays de la Loire (districts: 44 Loire-Atlantique; 49 Maine-et-Loire; 53 Mayenne; 72 Sarthe; 85 Vendée); and the remainder of France considered as one region. Of the 273 French BSE cases, 84 were from Brittany, 32 from Normandy, 50 from Pays de la Loire and 107 from elsewhere in France. Relative risks were calculated from per-head incidence rates, obtained for each region based on the French government’s annual statistics on the number of calves in each district.

The main analysis is restricted to the clinical cases detected through passive surveillance. A key uncertainty affecting the interpretation of the results of active surveillance programmes is the sensitivity of the test employed to detect infection 〚7, 8〛 as a function of the animal’s incubation period. Preliminary results from a study of cattle believed to be at higher risk of BSE (cattle found dead on farm, cattle subjected to euthanasia and cattle slaughtered as emergencies after an accident) gave a measured prevalence of 0.21%, 32 positive among 15 000 tested cattle, with significant variation between the risk groups 〚29〛. These results are analysed to obtain estimates of the infection prevalence in these high-risk groups of animals. More information would be required for a fully integrated analysis of clinical cases and positive animals detected through active surveillance testing programmes.

4 Results

Multiple analyses were conducted, varying assumptions regarding the survival distribution and the pattern of time-dependent underreporting. Comparisons are made between current model results and those published in 2000 〚19〛.

Earlier analyses were performed using the survival distribution estimated from British cattle 〚19〛. On the basis of the 138 cases confirmed at that time, it was estimated that roughly 1200 animals had been infected in France since mid-1987 (assuming complete reporting). Allowing for underreporting using a logistic function yielded a significantly better fit to the data (p < 0.001) and an estimated 6600 animals infected in that period. These estimates increased to 1400 and 8100, respectively, if the appropriate correction was made to the incompletely observed incidence cells, μ(c, a) where c + a = 2000, to adjust for reporting delay and any remaining incidence which might occur up to 29 June 2001 〚19〛.

Using the British estimated survival distribution, the corresponding updated estimates (Table 1, models 1 and 5) are increased to 2000 infections assuming complete reporting and 11 000 infections allowing for a logistic underreporting function with complete reporting from 2000 onwards. The model fit was significantly improved with the allowance for underreporting of clinical cases in 2000 (X2 = 65.5 – 47.5 = 20.0, p < 0.001), corresponding to an estimated 17 000 infections in French cattle since mid-1987. As in the previous analyses, logistic underreporting fits the data significantly better than assuming constant underreporting (p < 0.001 in each case). The estimates have increased and underreporting in 2000 was significant, because the combined incidence in the cells μ(c,a) where c + a = 2001 was substantially greater than predicted by the earlier model fits: 128 observed to date, expected to be 136 correcting for reporting delay and incomplete observation, compared to model predictions of between 30 and 80 (unpublished results of the published maximum likelihood fitted models 〚19〛).

Results of model fits (likelihood ratio statistic and estimated number of infections in French cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1997) assuming survival distributions estimated from British (B) and French (F) cattle and assuming underreporting is either logistic (L) or constant (C) in form with T = 2000 or 2001. The data are also analysed assuming reporting is complete (CR).

| Model number | Survival | Under-reporting | Likelihood ratio statistic | Estimated number of infections (95% CI) |

| 1 | B | L; T = 2000 | 65.5 | 11 000 |

| (4800–29 000) | ||||

| 2 | B | L; T = 2001 | 47.5 | 17 000 |

| (6900–47 000) | ||||

| 3 | B | C; T = 2000 | 98.9 | 3800 |

| (2900–5100) | ||||

| 4 | B | C; T = 2001 | 109.5 | 4500 |

| (3300–6000) | ||||

| 5 | B | CR | 173.7 | 2000 |

| (1800–2300) | ||||

| 6 | F | L; T = 2000 | 77.7 | 39 000 |

| (11 000–130 000) | ||||

| 7 | F | L; T = 2001 | 49.3 | 70 000 |

| (19 000–230 000) | ||||

| 8 | F | C; T = 2000 | 130.4 | 5500 |

| (4000–7500) | ||||

| 9 | F | C; T = 2001 | 142.4 | 6500 |

| (4700–8800) | ||||

| 10 | F | CR | 228.0 | 2400 |

| (2100–2700) |

Because the French estimated survival distribution predicted shorter lifetimes, the corresponding estimated numbers of infected animals were substantially greater (Table 1, models 6–10). As when using the British survival distribution, the best fitting model allowed for underreporting of clinical cases in 2000 (X2 = 77.7 – 49.3 = 28.4, p < 0.001) and a logistic underreporting function (model 7). This corresponded to a much larger estimated 70 000 animals infected since mid-1987.

The estimates of the total number of infections in cattle born between mid-1990 and mid-1997 show much less variability than estimates for the late 1980s (Table 2), with the best fitting models with British and French estimated survival distributions giving estimates of 4900 and 8400 infections, respectively, in these more recently born cattle. If reporting is assumed to be complete, the estimates are even more similar (1900 and 2200). In all cases, the analyses performed ignoring the data on cattle born prior to mid-1990 produced very similar estimates and confidence intervals for these cattle (Table 2) demonstrating the robustness of fits to the incidence data for these more recently born cattle.

Estimated numbers of infections in French cattle assuming survival distributions estimated from British and French cattle and assuming underreporting is either logistic or constant in form with T = 2000 or 2001. The data are also analysed assuming reporting is complete. The infections in cattle born between mid-1980 and mid-1997 varied little depending on whether they were fitted simultaneously with cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1990 (A) or fitted separately (B).

| Model number | Estimated number of infections | ||

| in cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1990 (95% CI) (A) | in cattle born between mid-1990 and mid-1997 (95% CI) | ||

| (A) | (B) | ||

| 1 | 7600 | 3400 | 3400 |

| (1700–25 000) | (2500–4600) | (2500–4500) | |

| 2 | 12 000 | 4900 | 4900 |

| (2700–42 000) | (3300–7000) | (3300–7200) | |

| 3 | 680 | 3200 | 3100 |

| (280–1400) | (2500–3900) | (2500–3900) | |

| 4 | 460 | 4100 | 4100 |

| (210–870) | (3000–5300) | (3000–5300) | |

| 5 | 140 | 1900 | 1900* |

| (86–200) | (1700–2100) | (1700–2100) | |

| 6 | 34 000 | 5300 | 5000 |

| (6500–120 000) | (3600–7900) | (3500–7900) | |

| 7 | 61 000 | 8400 | 8400 |

| (12 000–220 000) | (5200–13 000) | (5200–14 000) | |

| 8 | 1100 | 4300 | 4300 |

| (460–2400) | (3300–5600) | (3300–5500) | |

| 9 | 750 | 5800 | 5800 |

| (330–1400) | (4200–7700) | (4200–7700) | |

| 10 | 180 | 2200 | 2200* |

| (110–260) | (2000–2500) | (2000–2500) |

* When complete reporting is assumed, the estimates are by definition equivalent, because the infection incidence in each cohort is estimated independently.

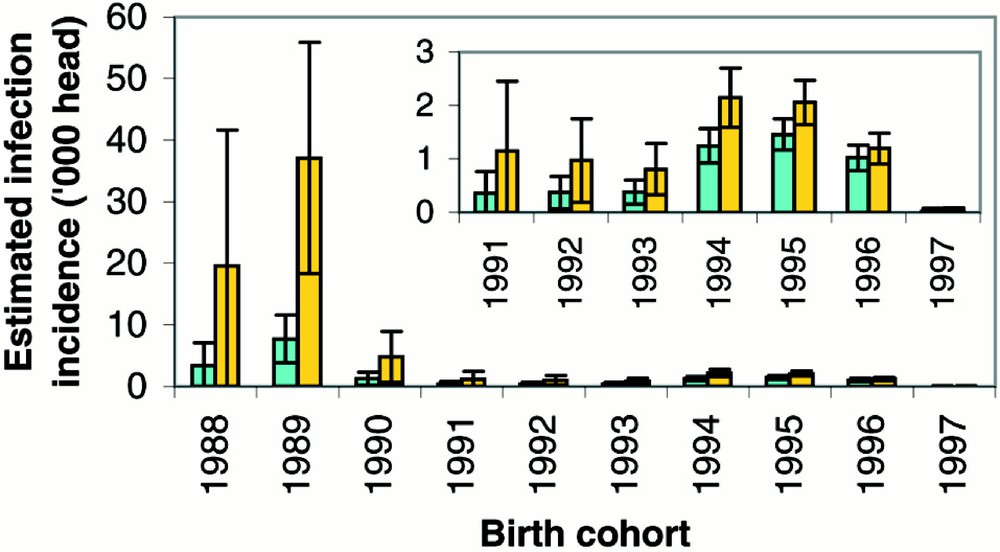

Cohort- and age-specific incidence rates (observed and fitted) demonstrate the good fit of the models allowing for underreporting (Fig. 3). The results, as in the previous analysis 〚19〛, for the best fitting models (2 and 7, both allowing for underreporting until 2001) indicate that the risk of infection was greatest in 1988 and 1989 (Fig. 4).

Estimated BSE infection incidence in French-born cattle by birth cohort (with 95% prediction intervals) using the survival distributions estimated from British (green) and French (gold) data assuming a logistic underreporting model.

Region-specific estimates were also obtained (Table 3), showing as in the national analyses substantially more uncertainty in the incidence of infections in cattle born prior to mid-1990. The relative risk of infection was considerably higher in Brittany in cattle born prior to mid-1990, subsequently the per-head incidence in Brittany was still elevated though similar to Normandy if the survival distribution estimated from French cattle was assumed. Combining Brittany, Normandy and Pays de la Loire into a single northwest region gave relative risks (compared to the rest of France) of between 13 and 29 for cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1990 and between 1.8 and 2.4 for cattle born between mid-1990 and mid-1997, depending on the model assumed.

Estimated numbers of infections in French cattle by region: Brittany (B), Normandy (N), Pays de la Loire (P) and the rest of France (R). Underreporting, when allowed for using a logistic model, was found to vary significantly (p < 0.01) when the survival distribution estimated from British cattle was assumed. However, it was not significant (p > 0.1) when the survival distribution estimated from French cattle was assumed. Relative risks of infection were obtained by taking the ratio of the per-head infection incidence in a region divided by that in the rest of France (region R). 〚Models assuming constant underreporting were omitted from the table due to their poor fit to the observed data.〛

| Model number | Regional differences in underreporting | Region | Estimated number of infections | Relative risk | ||

| in cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1990 (% of total) | in cattle born between mid-1990 and mid-1997 (% of total) | in cattle born between mid-1987 and mid-1990 | in cattle born between mid-1990 and mid-1997 | |||

| 1 | X2 = 17.1 p = 0.009 | B | 7300 (85%) | 940 (27%) | 47 | 2.5 |

| N | 290 (3%) | 290 (8%) | 3.3 | 1.4 | ||

| P | 280 (3%) | 540 (16%) | 1.6 | 1.3 | ||

| R | 730 (8%) | 1700 (49%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2 | X2 = 17.5 p = 0.008 | B | 34 000 (88%) | 1400 (26%) | 55.3 | 2.3 |

| N | 950 (2%) | 430 (8%) | 2.7 | 1.2 | ||

| P | 1000 (3%) | 740 (14%) | 1.4 | 1.1 | ||

| R | 2900 (7%) | 2800 (52%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 5 | — | B | 100 (70%) | 490 (25%) | 37 | 2.7 |

| N | 20 (13%) | 220 (11%) | 12 | 2.1 | ||

| P | 10 (9%) | 380 (20%) | 4 | 1.9 | ||

| R | 10 (9%) | 830 (43%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 6 | X2 = 9.9 p = 0.128 | B | 9700 (80%) | 1200 (25%) | 60 | 2.7 |

| N | 720 (6%) | 670 (14%) | 7.8 | 2.7 | ||

| P | 1000 (8%) | 950 (19%) | 5.6 | 1.9 | ||

| R | 750 (6%) | 2100 (42%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 7 | X2 = 10.6 p = 0.103 | B | 50 000 (82%) | 2000 (24%) | 68 | 2.6 |

| N | 2900 (5%) | 1300 (16%) | 6.8 | 3.0 | ||

| P | 4900 (8%) | 1600 (18%) | 5.9 | 1.8 | ||

| R | 3400 (6%) | 3600 (42%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| 10 | — | B | 130 (70%) | 580 (56%) | 37 | 2.7 |

| N | 20 (13%) | 260 (11%) | 12 | 2.1 | ||

| P | 20 (9%) | 460 (20%) | 4 | 1.9 | ||

| R | 20 (9%) | 980 (43%) | 1 | 1 |

Each model can be used to make projections of future clinical case incidence, stratified by age at onset, birth cohort, and year of onset as desired. Predicted incidence of confirmed clinical cases are presented (Table 4) by year of onset for each model. These do not include clinically unaffected positives identified through active surveillance screening of risk animals (such as fallen stock) or apparently healthy animals. Furthermore, because this analysis only estimates infections in animals born before mid-1997, no cases from animals born after this date are included in the projections.

Predicted incidence of confirmed clinical cases (with 95% prediction intervals) by year of onset for each model fitted to the national data as a whole. Clinical case predictions are presented for 2001 as well as 2002 and 2003, because not all BSE cases with clinical onset in 2001 will have been confirmed and recorded in the database by 8 January 2002.

| Model number | Clinical cases (95% prediction interval) | ||

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | |

| 1 | 84 | 43 | 17 |

| (60–110) | (28–58) | (8–26) | |

| 2 | 118 | 60 | 23 |

| (92–145) | (43–78) | (13–34) | |

| 3 | 85 | 44 | 17 |

| (63–110) | (29–59) | (8–26) | |

| 4 | 119 | 62 | 24 |

| (84–157) | (40–85) | (12–37) | |

| 5 | 62 | 34 | 14 |

| (38–90) | (17–53) | (4–25) | |

| 6 | 76 | 31 | 10 |

| (55–98) | (18–44) | (3–16) | |

| 7 | 116 | 46 | 14 |

| (79–157) | (27–67) | (5–24) | |

| 8 | 78 | 32 | 10 |

| (57–98) | (19–44) | (3–16) | |

| 9 | 118 | 48 | 15 |

| (83–155) | (29–68) | (6–24) | |

| 10 | 56 | 24 | 8 |

| (33–82) | (10–41) | (1–17) |

Table 5 gives the estimated prevalence rates assuming the diagnostic test was completely sensitive and assuming that the diagnostic test could only detect animals within 12, 24 and 36 months of clinical onset of disease, demonstrating the importance of test sensitivity and adjustment for age at testing in interpreting test-positive prevalence data 〚29〛. The tested high-risk cattle were found to be at substantially greater risk of infection (p < 0.001, odds ratio of 13 or greater, depending on assumptions) than cattle born at the same time.

Detected sample prevalence and corresponding infection prevalence estimates in cattle at higher risk of BSE (cattle found dead on farm, cattle subjected to euthanasia and cattle slaughtered as emergencies after an accident) for different assumptions regarding test sensitivity. The detected prevalence estimates and corresponding exact 95% confidence intervals are as previously reported by year of birth 〚29〛.

| Year of birth | Typical age (years) | Detected prevalence per 1000 cattle (95% CI) | Estimated prevalence per 1000 cattle assuming 100% sensitivity | |||

| Over the entire incubation period (95% CI) | For last 36 months (95% CI) | For last 24 months (95% CI) | For last 12 months (95% CI) | |||

| 1998 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 2.6 | 18 | 658 |

| (0–2.7) | (0–2.7) | (0.1–15) | (0.5–100) | (17–1000) | ||

| 1997 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–1.1) | (0–1.1) | (0–2.5) | (0–6.2) | (0–44) | ||

| 1996 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–1.6) | (0–1.7) | (0–2.3) | (0–3.6) | (0–10) | ||

| 1995 | 5 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 6.1 | 11 |

| (1.2–7.0) | (1.5–8.6) | (1.7–10) | (2.2–13) | (4.2–25) | ||

| 1994 | 6 | 8.9 | 17 | 19 | 22 | 35 |

| (5.0–15) | (9.3–27) | (10–30) | (12–36) | (20–57) | ||

| 1993 | 7 | 6.5 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 42 |

| (2.8–13) | (9.8–43) | (11–47) | (12–54) | (18–80) | ||

| 1992 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–4.3) | (0–31.1) | (0–34) | (0–38) | (0–55) | ||

| 1991 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–6.2) | (0–94) | (0–102) | (0–113) | (0–155) | ||

| 1990 | 10 | 2.6 | 91 | 98 | 109 | 149 |

| (0.1–14) | (2.5–361) | (2.7–379) | (3.1–408) | (4.4–498) | ||

| 1989 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–14) | (0–567) | (0–586) | (0–615) | (0–696) | ||

| 1988 | 12 | 5.3 | 537 | 556 | 585 | 668 |

| (0.1–29) | (0.1–867) | (31–876) | (34–889) | (50–920) | ||

| 1987 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (0–27) | (0–934) | (0–939) | (0–945) | (0–962) |

5 Discussion

The data clearly indicate that underreporting has been substantial in the early years of the epidemic and was significant even in 2000 (p < 0.001). Furthermore, comparison of the annual incidence predictions for 2001 (Table 4) with the 86 already recorded by 8 January 2002 reveals that the models assuming complete reporting underestimate the incidence in 2001, reinforcing the conclusion that models allowing for underreporting are more realistic. The previously published analysis 〚19〛 similarly found substantial underreporting improved the model fit to the data, but was unable to test underreporting in 2000. Similarly, this analysis is unable to test for underreporting in 2001.

The likelihood of clinical BSE cases being incompletely ascertained has not gone unrecognised by French officials. In 1995 managers of the epidemiological surveillance network reported that there was likely to be underreporting of suspected BSE cases due to decreasing motivation of veterinarians over time and a lack of acceptance of the programme by farmers 〚24, 25〛.

It should be noted that underreporting may have fluctuated over time, rather than being logistic or constant in form. However, it is not possible to reliably estimate underreporting non-parametrically. The results presented in this paper demonstrate the dependence of the results on underreporting assumptions (constant, logistic or complete). Clearly, more confidence can be placed on the results from models that provided a statistical good fit to the observed data.

French use of British meat and bonemeal greatly increased after mid-1988 when the British ban led to lower prices 〚25〛. A French ban on the use of any meat and bonemeal in cattle feed (regardless of country of origin) was implemented in 1990. Although not effectively enforced 〚26〛, this ban was estimated to have reduced infections by between 83% and 87%, comparing the estimated infection incidence in the 1990 birth cohort to that in the 1989 birth cohort. One explanation for the continuing risk after 1990 was cross-contamination from pig and poultry feed containing meat and bonemeal 〚27〛. The feed ban has been extended since this time and became much more rigorously enforced in 1996 〚28〛. The earlier analysis 〚19〛 was not able to estimate the effectiveness of these additional measures because no cases had yet been confirmed in animals born after mid-1996. Every model fitted to the incidence data currently available estimated a 97% reduction in infection incidence comparing estimated infection incidence in the 1996 and 1997 birth cohorts.

Although by 8 January 2002 only one clinical case of BSE (born in November 1996) had been confirmed in cattle born after June 1996, ten such BSE-infected animals have been detected through active surveillance (the most recently born was born in October 1997). Backcalculation analyses should be updated regularly to assess any divergence of the incidence of clinical cases from that predicted from previously confirmed cases. It should be recognised, however, that the accumulation of additional years of data even with perfect reporting of complete cases would not substantially reduce the uncertainty about the early trends in infection incidence. The confidence intervals reflect the uncertainty in both the estimated underreporting parameters and cohort-specific incidence rates, and new cases provide little information on the early reporting patterns.

Particular care is required in incorporating data on positives detected in active surveillance, whether in risk animals or in apparently healthy cattle slaughtered for consumption. While these tests detect infections in animals slaughtered prior to clinical onset, they are not completely sensitive and in particular may miss cases not in the late stages of the incubation period 〚7, 8〛. For this reason, the pattern of birth-cohort-specific infection prevalence estimated in studies comparing animals of different ages, such as the pilot study in northwestern France (Brittany, Normandy and Pays de la Loire) involving animals born from before 1983 to 1998 〚29〛, cannot be assumed to reflect the relative number of infections in the cohorts.

Worldwide attention has remained focussed on BSE with its association with vCJD in humans 〚30–32〛. To date, among French nationals there have been three confirmed cases of vCJD 〚33–36〛, with a fourth death recently reported and a fifth person believed to be living with the symptoms of the disease 〚37〛. Although considerable effort has been focussed on analysis of the vCJD epidemic in Great Britain where just over 100 cases of vCJD have been identified to date 〚38–44〛, such detailed analysis has not yet been applied to the French epidemiological setting. To do so rigorously would require key extensions to the methods developed and applied in the British context.

Firstly, due to the vast majority of clinical cases of BSE arising in Great Britain, the exposure of the British population via meat and meat products has arisen from domestic cattle slaughtered for consumption prior to clinical onset of the disease. Full consideration of the exposure of the French population to potentially infectious meat and meat products requires careful consideration of the origin and timing of meat importation from the United Kingdom but also other BSE-affected countries, taking account of the country-specific pattern of clinical case reporting through time.

Secondly, unlike the United Kingdom, France has operated a whole herd slaughter policy, compulsory from 1994, but typically implemented for earlier cases as well 〚25〛. The specified bovine offal (SBO) of these cattle was incinerated, but the non-SBO tissues were not removed from the food supply 〚25〛. Thus, although the subsequent incidence of BSE cases was reduced by this policy if infections were clustered in herds, predictive models of vCJD incidence will need to allow for the consumption of potentially infected (and thus potentially infectious) animals slaughtered in this policy.

Indeed a topic of ongoing research is to examine whether estimates of infection incidence can be improved by allowance for the whole herd slaughter policy. Current consideration is being given to France operating a more limited culling policy, perhaps cohort-based within the herd. Given such a policy, information gained from monitoring such herds after the confirmation of the first BSE case could provide important information on the nature of infection clustering within French cattle herds.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to David Barnes, Agriculture Attaché at the British Embassy in Paris for obtaining French annual agricultural statistics and to Peter Hambly for translation. The research funding provided by the Wellcome Trust made this work possible.

Version abrégée

1 Introduction

L’encéphalopathie spongiforme bovine (ESB) fut diagnostiquée pour la première fois en Angleterre vers la fin de l’année 1986. En Grande-Bretagne, on décréta que la déclaration de la maladie serait obligatoire, et l’interdiction de l’emploi de protéines d’origine ruminante dans la production de la nourriture pour ruminants entra en vigueur en 1988. Quoique cette interdiction abaissât de façon dramatique l’incidence des infections, elle ne fut pas totalement efficace. En raison de la longue période d’incubation, l’impact de telles interventions ne sera sensible que dans quelques années. Ainsi, l’incidence annuelle de cas cliniques en Grande-Bretagne atteignit un pic en 1992, avec plus de 178 000 cas cliniques confirmés jusqu’ici.

Des épidémies de moindre ampleur se sont produites ailleurs en Europe, l’Irlande du Nord, la Suisse, la république d’Irlande, le Portugal et la France enregistrant des centaines de cas cliniques. D’autres pays, tant dans l’Union européenne (UE) qu’à l’extérieur de l’Union, ont enregistré des cas cliniques en petit nombre.

Outre les cas cliniques, la surveillance active (tout le bétail de plus de 30 mois abattu pour la consommation doit subir le test de l’ESB) donna lieu à des tests positifs parmi des bêtes en apparence saines (c’est-à-dire celles abattues normalement) dans nombre de pays européens. Quoique les tests ne soient pas suffisamment sensibles pour détecter toutes les bêtes infectées, on n’appliqua pas de limites d’âge à la consommation d’animaux testés négatifs, en raison de l’incidence relativement basse de l’infection ESB en dehors du Royaume-Uni. À l’intérieur du Royaume-Uni, le risque d’exposition d’êtres humains au bœuf potentiellement infectieux a été réduit dans des proportions considérables, grâce à la disposition ordonnant que seuls les bovins de moins de 30 mois seraient abattus pour la consommation.

Les analyses, basées sur des calculs rétrospectifs, des données relatives à l’incidence clinique de l’ESB ont révélé que, en raison de la période moyenne d’incubation, longue en comparaison de la vie moyenne du bétail, la plupart des bovins infectés ont été abattus pour la consommation avant qu’ils ne connaissent l’attaque des signes cliniques de la maladie. On a estimé que quelque 900 000 bovins ont été infectés au cours de l’épidémie en Grande-Bretagne. Les modèles de calculs rétrospectifs ont aussi fourni des prévisions d’une haute exactitude en ce qui concerne l’incidence clinique future de l’ESB.

En 1989, des scientifiques envisagèrent l’éventualité de l’existence de l’ESB dans le cheptel français, en suggérant que de possibles infections dues à la consommation de farines de viande et d’os importées de Grande Bretagne, entre juin 1988 (année qui vit l’interdiction de l’employer dans la nourriture pour ruminants en Grande-Bretagne) et août 1989, pourraient donner lieu à des cas de déclaration de la maladie à partir de 1991 (le retard étant dû à la longue période d’incubation de celle-ci). Le réseau français de surveillance épidémiologique de l’ESB, établi en décembre 1990, identifia le premier cas d’ESB en février 1991.

Ce ne fut qu’en 2000 que l’attention du grand public se focalisa en France sur l’ESB, au moment où l’on constata l’augmentation de l’incidence de cas cliniques confirmés. Dans le même temps, l’incidence clinique dans les épidémies britannique, irlandaise, suisse et portugaise allait en diminuant. L’analyse épidémiologique réalisée en France (basée sur des cas cliniques confirmés et enregistrés avant le 17 novembre 2000) indiqua qu’au moins 1200 bovins français avaient été infectés depuis la mi-1987.

La présente analyse épidémiologique étendue révise l’importance de l’épidémie, grâce à l’année supplémentaire de données relatives aux cas cliniques dont on dispose actuellement, fournissant des prévisions de cas futurs et des analyses de sensibilité. Elle analyse aussi les résultats de l’étude pilote concernant la France du Nord-Ouest (la Bretagne, la Normandie et les pays de la Loire) et portant sur 15 000 bovins.

2 Méthodes

Les tendances en ce qui concerne l’incidence de l’infection et la sous-déclaration, compte tenu de la variation selon la durée, ne peuvent être démêlées que par une analyse patiente de l’incidence observée selon l’âge et la cohorte. L’incidence prédite des cas d’ESB est donnée par le produit des facteurs suivants : le nombre d’infections dans la cohorte de naissances c ; la probabilité qu’un animal infecté connaisse l’attaque clinique à l’âge a ; la probabilité qu’un animal survive jusqu’à l’âge a ; la probabilité qu’un animal, qui fait partie de la cohorte c, dont l’attaque de la maladie se produit à l’âge a, ait été déclaré aux pouvoirs publics.

La distribution pour l’âge de l’attaque est estimée par la convolution de la fonction d’exposition/susceptibilité selon l’âge et de la distribution de la période d’incubation, en utilisant les estimations de paramètres validées obtenues par le modèle le plus adéquat, basé sur les calculs rétrospectifs relatifs à l’épidémie en Grande-Bretagne.

Les distributions pour la survie, qui ont fait l’objet d’estimations indépendantes pour les bovins britanniques, portugais et français, suggèrent que les bovins européens continentaux ont une durée de vie moyenne plus courte. Les probabilités de survie réduites augmentent le nombre estimé d’animaux infectés nécessaire pour donner lieu au nombre de cas enregistrés.

Un certain nombre de formes paramétriques fut examiné pour la fonction de sous-déclaration, qui varie selon la durée. Comme on l’a vu plus haut, il est impossible d’imposer une probabilité de sous-déclaration à l’épidémie dans son entier, en l’absence de données indépendantes en ce qui concerne les taux de déclaration. L’analyse en cours est capable de tester la signification de la sous-déclaration en 2000, mais présuppose une déclaration totale en 2001.

Les paramètres qui reflètent l’incidence suivant la cohorte et la sous-déclaration furent estimés par le recours aux méthodes de vraisemblance maximale, en supposant que les données sur l’incidence clinique sont le résultat d’une distribution de Poisson.

L’analyse des données fournies par les tests faits sur les bêtes pré-cliniques exige un ajustement, qui tient compte de la proportion de bêtes infectées toujours en vie à l’âge ou l'animal a été testé et la sensibilité du test en fonction de la durée d’incubation.

3 Données

Cette analyse se borne surtout aux cas cliniques détectés dans le cadre de la surveillance passive. Des détails concernant des cas individuels d’ESB sont disponibles à l’Agence française de sécurité sanitaire des aliments et au ministère de l’Agriculture et de la Pêche. En réunissant ces sources de renseignements, il est possible d’obtenir la date de soupçon, le mois et l’année de naissance ainsi que le département, pour chaque cas confirmé d’ESB. L’année et l’âge au moment de l’attaque clinique sont tous deux déterminés sur la base de la date de soupçon enregistrée. Les résultats préliminaires fournis par une étude des bovins qu’on jugeait exposés à un degré de risque plus élevé (bovins qu’on trouva morts sur une ferme, bovins enthanasiés et bovins abattus d’urgence après un accident) donnèrent une fréquence évaluée à 0,2%, soit 32 cas positifs parmi les 15 000 bovins testés, avec une variation significative selon les groupes à risque.

4 Résultats

Des analyses antérieures avaient été réalisées en utilisant la distribution pour la survie estimée d’après celle des bovins britanniques. Sur la base de 138 cas confirmés à cette époque, et en faisant les modifications nécessitées par le caractère incomplet de l’enregistrement, on estima que 8100 animaux avaient été infectés en France depuis la mi-1987, si l’on tient compte d’une sous-déclaration significative ; cette estimation tombe à 1400 ; si l’on en croit la déclaration complète.

Si l’on emploie la distribution pour la survie estimée par les Britanniques, les estimations correspondantes mises à jour (Tableau 1, modèles 1 et 5) montent à 2000 infections, si l’on en croit la déclaration complète, et à 11 000 infections, si l’on tient compte d’une fonction logistique de la sous-déclaration et qu’on suppose une déclaration totale à partir de 2000. L’adéquation du modèle fut améliorée en tenant compte de la sous-déclaration de cas cliniques en 2000 (p < 0,001), ce qui correspond à une estimation de 17 000 infections dans le bétail français depuis la mi-1987. Comme dans les analyses antérieures, la sous-déclaration logistique donne une bien meilleure adéquation que la présupposition d’une sous-déclaration constante (p < 0,001 dans chaque cas).

Parce que l’estimation de la distribution pour la survie faite en France prédisait des durées de vie plus courtes, l’estimation du nombre d’animaux infectés était notablement plus grande (Tableau 1, modèles 6–10). De même, quand on utilisait la distribution pour la survie réalisée par les Britanniques, le modèle le plus adéquat tenait compte de la sous-déclaration des cas cliniques en 2000 (p < 0,001) et d’une fonction de sous-déclaration logistique (modèle 7). Cela correspondait à l’estimation d’un plus grand nombre de bêtes infectées, à savoir 70 000, depuis la mi-1987.

Les taux d’incidence suivant l’âge et la cohorte (constatés et ajustés) démontrent la bonne adéquation des modèles, compte tenu de la sous-déclaration et, comme dans l’analyse précédente, indiquent que le risque d’infection fut à son plus haut point en 1988 et 1989.

Les incidences de cas cliniques confirmés prédites sont présentées (Tableau 4), selon l’année de l’attaque, pour chaque modèle. Ces incidences ne tiennent pas compte des tests positifs portant sur des sujets cliniques sans infection, identifiés par une surveillance active d’animaux à risque (tels que le bétail tombé) ou sur des animaux apparemment sains. En outre, parce que cette analyse n’estime que les infections chez des animaux nés avant la mi-1997, aucun cas chez des animaux nés après cette date ne figure dans les projections.

Dans le Tableau 5, le taux estimé de fréquence présuppose que le test diagnostique a été parfaitement sensible et que le test a détecté les seules bêtes infectées dans une période de 12, 24 ou 36 mois depuis l’attaque clinique de la maladie. On voit que les bovins à hauts risques testés furent bien plus susceptibles d’être infectés (p < 0,0001) que les bovins nés à la même époque.

5 Discussion

Les données indiquent clairement que la sous-déclaration était considérable dans les premières années de l’épidémie et restait encore significative en 2000 (p < 0,001). De manière semblable, l’analyse précédemment publiée a montré qu’une sous-déclaration considérable a amélioré l’adéquation du modèle aux données, mais qu’elle n’était pas apte à déterminer la sous-déclaration en 2000. De même, cette analyse n’est pas apte à déterminer la sous-déclaration en 2001.

Les pouvoirs publics reconnaissent en France qu’il est vraisemblable que tous les cas cliniques n’ont pas été enregistrés. En 1995, les responsables du réseau de surveillance épidémiologique rapportèrent qu’il était probable que les cas d’ESB soupçonnés étaient sous-déclarés, en raison de la démotivation croissante des vétérinaires et du refus de la part des agriculteurs d’accepter le programme.

Il faut manifester une prudence toute particulière en incorporant des données sur des tests positifs détectés dans la surveillance active, que ce soit pour les animaux à risque ou pour les bovins apparemment sains abattus pour la consommation. Tandis que ces tests détectent des infections chez des animaux abattus avant l’attaque clinique, ils ne sont pas complètement sensibles et, en particulier, ils peuvent laisser inaperçus des cas intervenus hors de la dernière période d’incubation. Pour cette raison, l’image de la fréquence d’infections selon la cohorte, estimée dans une étude qui compare des animaux d’âges différents, telle que l’étude pilote réalisée dans le Nord-Ouest de la France, ne peut refléter avec certitude le nombre relatif d’infections intervenues dans les cohortes.

L’attention se focalise dans le monde entier sur l’ESB, qui s’associe à la maladie de Creutzfeldt–Jakob (v-MCJ) chez les êtres humains. Jusqu’à présent, on a observé trois cas confirmés de v-MCJ en France, auxquels il faut ajouter un quatrième décès, annoncé récemment, et une cinquième personne, qui semble présenter les symptômes de la maladie. Si des efforts considérables ont été déployés pour l’analyse de la v-MCJ en Grande-Bretagne, où l’on a identifié jusqu’ici un peu plus de 100 cas de v-MCJ, on n’a pas fait une analyse aussi détaillée de l’épidémie du côté français. Pour entreprendre ce travail, il faudrait étendre les méthodes pointues qu’on a développées et appliquées au contexte britannique.

Premièrement, si l’on veut faire un examen détaillé de l’exposition de la population française à la viande et aux produits carnés potentiellement infectieux, il faudra examiner avec soin, non seulement l’origine et la date de l’importation de la viande du Royaume-Uni, mais aussi dans les autres pays où se sont déclarés des cas d’ESB, tout en tenant compte du profil de chaque pays au niveau de la déclaration de cas cliniques pour une période donnée. En second lieu, à la différence du Royaume-Uni, la France a mis en œuvre une politique d’abattage de troupeaux entiers. On a procédé à l’incinération des abats spécifiés bovins (ASB) de ces bêtes, mais les autres parties (non-ASB) n’ont pas été retirées de la chaîne alimentaire. Ainsi, s’il est vrai que l’incidence ultérieure de cas d’ESB a été réduite par cette politique, à condition que les infections aient été regroupées en troupeaux, des modèles à valeur prédictive de v-MCJ devront tenir compte de la consommation d’animaux infectés (et par conséquent potentiellement infectieux) abattus conformément à cette politique. Un sujet de recherche qui s’impose donc est de déterminer si les estimations de l’incidence de l’infection peuvent être améliorées en tenant compte de la politique d’abattage de troupeaux entiers.