1 Introduction

Population genetics and phylogenetic relationships among hare species are poorly known and confused [1,2]. Four species are present in Italy: L. timidus (mountain hare) is distributed in the Alps, with relatively undisturbed populations. L. capensis mediterraneus (mediterranean hare) was introduced by humans in Sardinia during historical times, from populations of L. capensis (Cape hare), probably located in north Africa or the Middle East. Taxonomy of the Cape hare is still unresolved, thus it is not clear whether the mediterranean hare should be considered a subspecies (L. capensis mediterraneus; [3]) or a true species (L. mediterraneus; [4]). L. corsicanus (Italian hare) is an endemic form, present in central-southern Italy and Sicily, it was first described and classified as a true species in 1898 [5], but later its status was changed and reconsidered as subspecies of L. europaeus [6], only recently morphological and molecular data reevaluated the italian hare to the status of true species [7–9]. L. europaeus (brown hare) was originally widespread in northern and central Italy with the autochtonous form L.e. meridiei, which might have been replaced by introduced brown hares belonging to different subspecies. Molecular data suggest that continental populations of brown hare are poorly differentiated [9]; however, ancestral and divergent mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) haplotypes were found in individuals sampled in refugial areas in Italy [9] and in Greece [10].

Human activities strongly affected presence, distribution and densities of hares in Italy. L. corsicanus was the only species present in central and southern Italy, where overhunting and massive restockings with brown hares of admixed genetic composition likely caused a marked reduction of its population size and distribution areas. Where such practices are legal, both species are present and in competition for resources. Thus the brown hare is considered a major threat to the integrity of native populations of the Italian hare. Gene flow between introduced brown hares and indigenous mountain hares has already been observed in Sweden; moreover hybrid individuals are likely to have a selective disadvantage in the wild [11]. Hybridization between Italian and introduced brown hares is thus thought as a potential concern for the integrity of the gene pool of L. corsicanus.

2 Results

62 samples of L. corsicanus, 72 of L. europaeus, 21 of L. capensis mediterraneus and 4 of L. timidus were collected in different localities in Italy (Fig. 1). Moreover samples of L. granatensis from Spain, L. capensis from central and South Africa, and one sample each of L. habessinicus and L. starki were collected in order to define the phylogenetic relationships of hares present in Italy. Samples were “a priori” classified on the basis of their morphology and geographic origin.

Sampling localities of hares in Italy. Circles: L. europaeus, triangles: L. corsicanus, squares: L. capensis mediterraneus, stars: L. timidus.

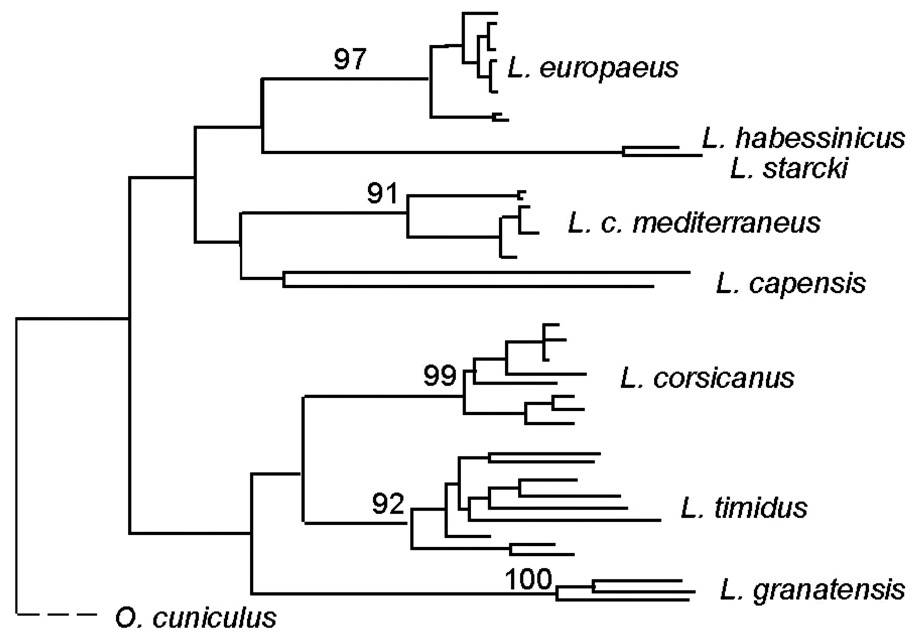

The hypervariable domain I of the control region (CR-I) of mtDNA was amplified by PCR and 293–295 nucleotides were sequenced. Phylogenetic analyses showed that: (1) haplotypes of the Italian hare cluster together in a single monophyletic group and (2) the Italian and the brown hare do not share haplotypes (Fig. 2). Thus molecular and morphological data warranted the status of true species for the Italian hare L. corsicanus.

NJ tree representing phylogenetic relationships among taxa. Numbers represent bootstrap percentage after 1000 resamplings.

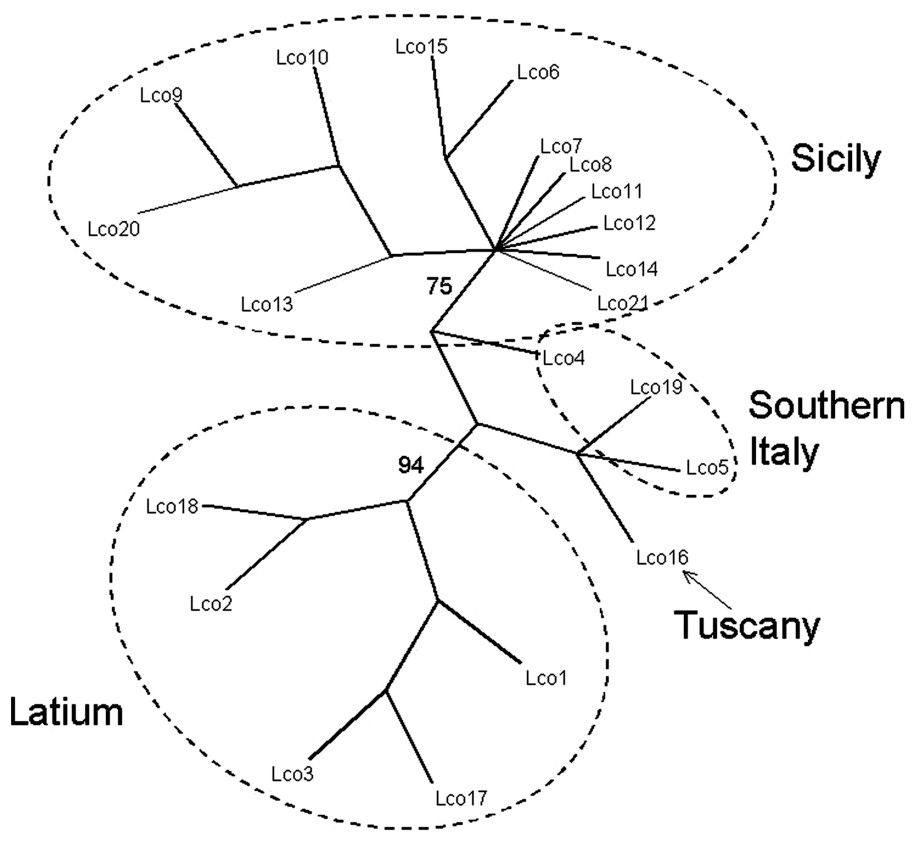

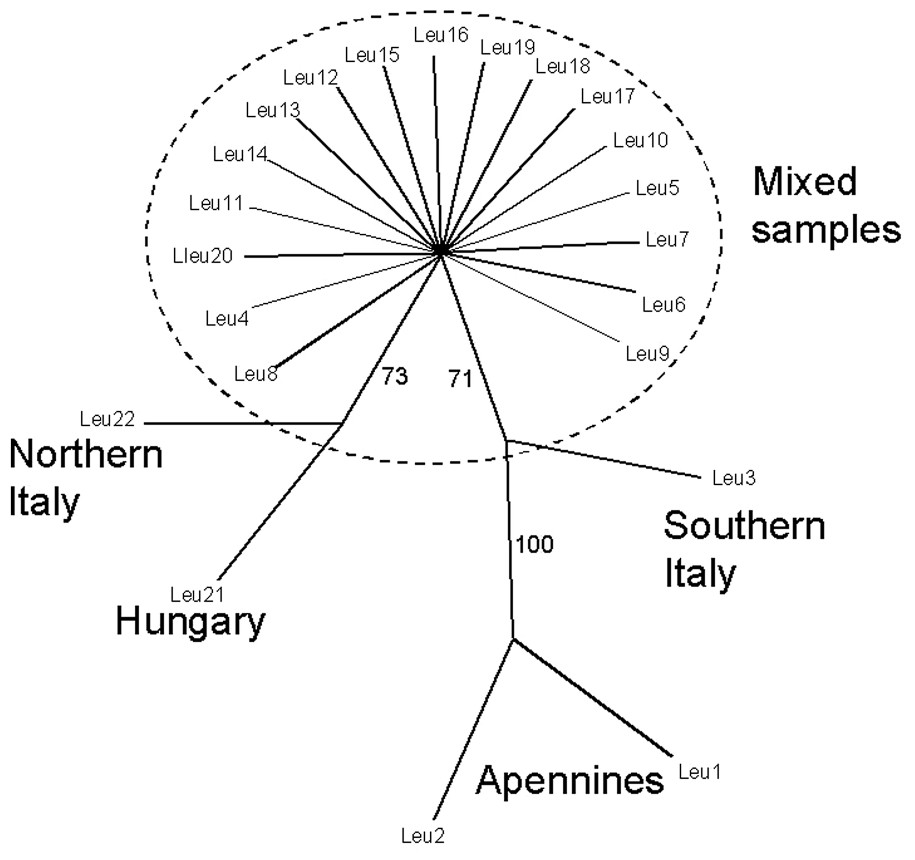

Estimated levels of intraspecific variation showed that L. corsicanus and L. europaeus have similar levels of variability, while variability within L. timidus was three times higher, suggesting a higher historical effective population size (Table 1). Inferences on past demographic histories were made by mismatch distribution analysis [12], results showed that L. corsicanus had a stable population size over historical times, while L. europaeus and L. timidus showed a clear population expansion during recent ( years ago) and past ( years ago) historical times, respectively. Pattern of genetic variation within L. corsicanus was found significantly correlated with the geographic origin of samples: a neighbor-joining (NJ) clustering procedure produced a tree where haplotypes sampled in central Italy grouped together and apart from haplotypes sampled in southern Italy and Sicily (Fig. 3). Analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA, [13]) indicated high and significant Fst values (Fst=0.74, P<0.001). No evidence of genetic structure could be detected within L. europaeus, most of the haplotypes clustered together in a star-like structure in a NJ tree (Fig. 4). However some ancestral and divergent haplotypes were found in individuals sampled in remote localities in the Apennines, suggesting the hypothesis that some populations of the subspecies L.e. meridiei could still persist in those areas. Phylogenetic relationships and estimated divergence times suggest that hares in Europe can be divided in two clades (Fig. 2): clade A (L. corsicanus, L. timidus and L. granatensis) and clade B (L. europaeus, L. habessinicus, L. starki and L. capensis). Species belonging to clade A are now confined in areas indicated as glacial refugia, where repeated cycles of population contraction and isolation mediated allopatric speciation, while clade B is formed by species of African distribution with the exception of L. europaeus. It is therefore tempting to speculate a scenario in which species belonging to clade A originated from a common ancestor during an early phase of dispersal through Europe, followed by events of isolation in restricted areas, caused by habitat changes and/or competition with another species (L. europaeus) that dispersed through central Europe in relatively recent times.

Values of interpopulation genetic diversity in Italian, brown, mountain and mediterranean hares

| Species | Haplotypes/ | Polymorphic | Mutations | Haplotype | Nucleotide | Pairwise |

| samples | sites/total | (Ts/Tv) | diversity | diversity | differences | |

| L. corsicanus | 21/62 | 30/295 | 24/5 | 0.856±0.038 | 0.018±0.009 | 5.35±2.61 |

| L. europaeus | 22/72 | 29/294 | 26/4 | 0.891±0.020 | 0.019±0.010 | 5.49±2.67 |

| L. timidus | 16/19 | 59/295 | 56/9 | 0.977±0.027 | 0.057±0.029 | 16.92±7.70 |

| L.c. mediterraneus | 9/22 | 15/295 | 11/2 | 0.870±0.042 | 0.014±0.008 | 4.15±2.15 |

Unrooted NJ tree representing relationships among L. corsicanus haplotypes. Numbers represent bootstrap percentage after 1000 resamplings.

Unrooted NJ tree representing relationships among L. europaeus haplotypes. Numbers represent bootstrap percentage after 1000 resamplings.

3 Discussion

MtDNA and morphologic data indicate that the Italian hare is an endemic species, originated through events of isolation in glacial refugia in Southern Italy. Intraspecific genetic diversity indices and AMOVA analysis indicated that genetic variation in L. corsicanus is high and significantly partitioned among geographic populations, haplotypes sampled in central Italy are significantly differentiated from those sampled in southern Italy and Sicily. Mismatch distribution of pair wise differences in the mtDNA control region showed that population size has been historically stable. Finally, no signs of introgression with L. europaeus could be detected. Overhunting and releasing of stocked brown hares caused the erosion and fragmentation of the distribution of the Italian hare, which now survives at low densities and in competition with the brown hare in central and southern Italy. Despite massive releasing during past decades, no vital populations of brown hares have been detected in Sicily, where the Italian hare is the only species present; it is therefore possible that the brown hare is not fitted for the Mediterranean-type of environment typical of the island. At present, releasing of stocked brown hares is not allowed in Sicily. The uniqueness of L. corsicanus and the concern about its conservation prompted the Italian Ministry of Environment to the creation of a multidisciplinary working group in order to set up the guidelines for the conservation of the Italian hare. These guidelines were resumed in the national action plan for the Italian hare [14].

4 The national action plan for the Italian hare

An interdisciplinary working group was established in order to coordinate the different actions at national and local scale. People involved belong to different public research and management institutions, to non-government environmental associations and to hunting associations. The action plan is subdivided into seven key actions, within each action different aspects of research and management of the Italian hare, information to scientific and public communities, and the implementation of the plan are discussed.

Action 1: Establishment of the working group with the aim to coordinate national an local institutions in the implementation of the plan.

Action 2: Assignment of the Italian hare to the correct national and international legal framework.

Action 3: Definition of the distribution of the Italian hare, conservation and management of local populations in order to increase densities, identification of particularly endangered populations. Creation of ecological “corridors” through which individuals can disperse, thus re-establishing gene flow among isolated populations. Creation of areas where hunting is banned around reserves and national parks where the density of the Italian hare is still high, in order to favour natural recolonization from “healthy” populations.

Action 4: Identification and reduction of harmful factors. Releasing of stocked brown hares in central and southern Italy is a dangerous practice for the Italian hare because of interspecific competition for food resources; moreover the brown hare represents a source of diseases which can potentially affect the Italian hare. L. corsicanus was in fact found susceptible to the European Brown Hare Disease. Hybridisation between the two species is considered a possible event, and should be continuously monitored through genetic analysis. Poaching is believed to be one of the major causes of death of the Italian hare. Actions to prevent it, especially in low densities areas, should be implemented.

Action 5: Improvement of the basic knowledge in the fields of biology, genetics, ecology and veterinary.

Action 6: Application of the principle of a “sustainable hunting activity” to hare species. The practices of restocking and translocations, which are common for the brown hare, should be abandoned in central and southern Italy, and a maximum number of individuals that can be harvested each year in each area should be defined.

Action 7: Communication of the results of the plan in order to awaken the public opinion to the problem of conservation of the Italian hare. Particular care should be paid to hunting associations, to actively involve them in the actions where a knowledge of the territory is needed and to increase the sensibility and responsibility of hunters to the sustainable management of the territory.