1 Introduction

The lion (Panthera leo, L. 1758) once roamed large parts of Africa, Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The species disappeared from Europe during the first century AD and from North Africa, the Middle East and Asia between 1800 and 1950, except one population in India, containing approximately 250 lions of the sub-species P. l. persica. The sub-species P. l. africana now lives in savanna habitats across sub-Sahara Africa [1].

The African lion is classified as vulnerable on the Red List of Threatened Species of the World Conservation Union (IUCN); agriculture, human settlement and poisoning are mentioned as main threats. The lion is a member of the family Felidae which is listed in appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Institutions involved in nature conservation do not generally focus on lions.

Lion numbers were estimated at between 30 000 and 100 000 in 1996 [1]. Populations in West and Central Africa were then described as largely unknown but probably declining. A recent unpublished inventory by the IUCN African Lion Working Group, the African Lion Database, shows that the number of lions in Africa is more likely between 18 000 and 27 000 (http://www.african-lion.org/ald_2002.pdf). Here, we focus on the West and Central African part of that inventory and describe numbers, trends, threats and opportunities with regard to lion conservation in West and Central Africa.

2 Material and methods

The study is based on extensive inquiries, the fact that almost every single country was covered indicates that there are few gaps. More research on currently known lion populations will improve precision but is not expected to change the estimate substantially. Figures are presented as unrounded figures, except sub-totals and totals which are presented as rounded to the nearest 100. Only a few figures were found in literature, very few census data have been published, most are therefore based on guesstimates by informants with knowledge of the area.

3 Results and discussion

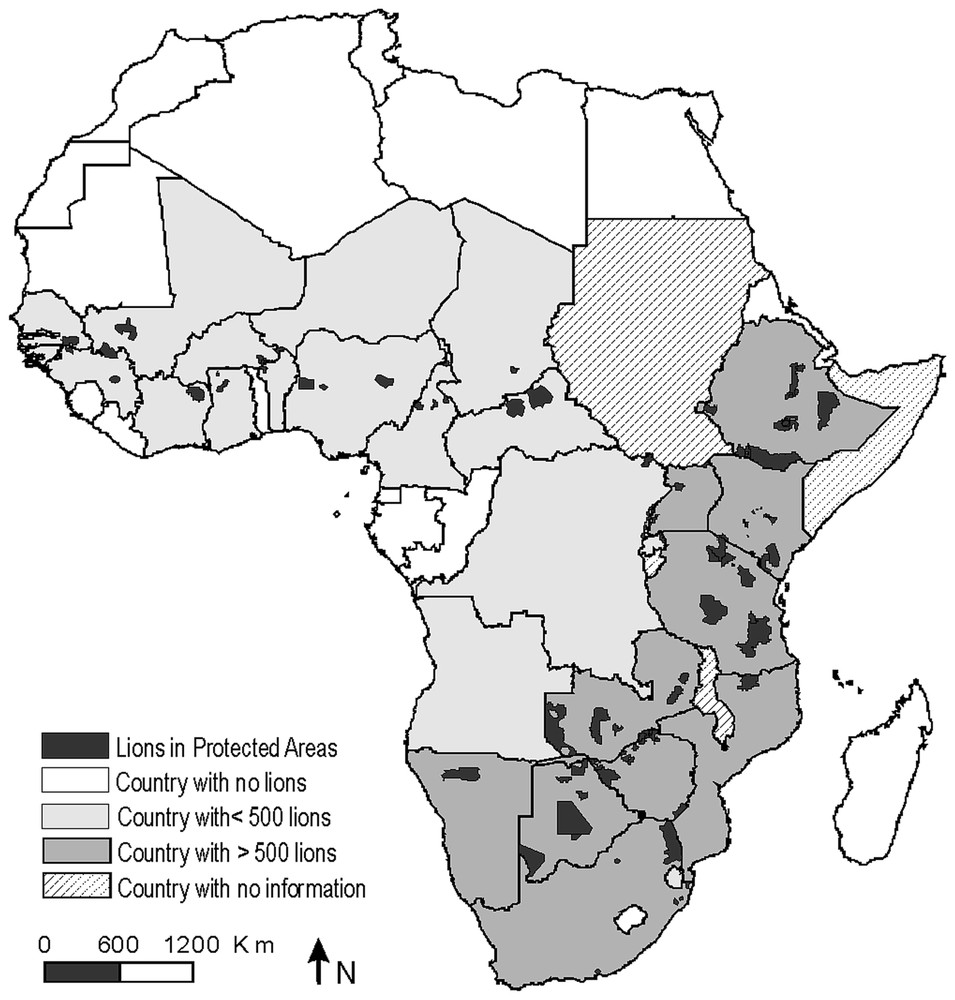

The African Lion Database estimates the number of free ranging lions in West and Central Africa at 1700 (lowest and highest conceivable estimate or “min-max”: 1200–2700; Table 1). Fig. 1 highlights that all populations are small and fragmented, scattered over the region.

Lion population estimates in West and Central Africa. Figures are educated guesses of likely, minimum and maximum population size, respectively

| Region | Country | Ecosystem | Estimate | Min | Max | Source |

| North Africa | All countries | All ecosystems | 0 | 0 | 0 | [1] |

| West Africa | Benin | Pendjari ecosystem | 50 | 38 | 63 | Tehou, Di Silvestre (pers. com.) |

| Benin | Remainder | 20 | 15 | 25 | Tehou (pers. com.) | |

| Burkina Faso | Arly ecosystem | 75 | 49 | 101 | Bouche (pers. com.) | |

| Cote d'Ivoire | Comoe NP | 30 | 20 | 40 | Fischer (pers. com.) | |

| Gambia | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | Pers. obs. | |

| Ghana | Gbele Reserve | 10 | 8 | 13 | Ghana Wildlife Society (pers. com.) | |

| Ghana | Mole NP | 20 | 15 | 25 | Ghana Wildlife Society (pers. com.) | |

| Guinea | National | 200 | 150 | 250 | Oulare (pers. com.) | |

| Guinea-Bissau | Doulombi/Boe NP | 30 | 23 | 38 | Fai (pers. com.) | |

| Liberia | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | [17] | |

| Mali | National | 50 | 33 | 68 | Moriba (pers. com.) | |

| Mauritania | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | [1] | |

| Niger | “W” NP | 70 | 60 | 81 | Moussa, Gay (pers. com.) | |

| Nigeria | National | 200 | 130 | 270 | Jenkins (pers. com.) | |

| Senegal | Niokola Koba ecosystem∗ | 60 | 20 | 150 | Burnham, Diop, Di Silvestre (pers. com.) | |

| Sierra Leone | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | [17] | |

| Togo | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | [1] | |

| Sub-total | 800 | 600 | 1100 | |||

| Central Africa | Cameroon | Benoue ecosystem | 200 | 100 | 400 | Aarhaug (pers. com.), pers. obs. |

| Cameroon | Waza NP | 50 | 30 | 70 | Pers. obs. | |

| Central African Republic | National | 300 | 200 | 500 | Scholte (pers. com.) | |

| Chad | Zakouma ecosystem | 50 | 38 | 63 | Scholte (pers. com.) | |

| Chad | Remainder | 100 | 50 | 150 | Scholte (pers. com.) | |

| Congo | Odzilla NP∗ | 0 | 0 | 25 | Anderson, Aveling (pers. com.) | |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | Virunga NP | 90 | 60 | 125 | Languy (pers. com.) | |

| Dem. Rep. Congo | Garamba NP | 150 | 100 | 200 | Smith, Languy (pers. com.) | |

| Equatorial Guinea | National | 0 | 0 | 0 | [1] | |

| Gabon | National∗ | 0 | 0 | 50 | [1], Henschl (pers. com.) | |

| Sub-total | 900 | 600 | 1600 | |||

| Total | 1700 | 1200 | 2700 |

∗ Disputed.

Lion distribution in Africa.

Wildlife densities in any central and west African ecosystem have always naturally been much lower than in eastern Africa, generally speaking, in the order of magnitude of 500–2500 kg/km2. This means that lion densities have probably always been much lower than in other parts of the continent. Following the correlation between lean season biomass and lion density [2], it probably varied between 1 and 20 lions per 100 km2. With the increase in human pressure, lions have virtually disappeared from non-protected areas, and lion densities in most protected areas are now below 5 lions per 100 km2.

In West and Central Africa, lion populations appear to be small and isolated; they have virtually disappeared from non-protected areas. Scarce information suggests a decline over the last three decades in protected areas, illustrated by changes in four reputed National Parks (NP): Niokolo Koba NP in Senegal from 120 to 70 [3], Comoé NP in Ivory Coast from 100 to 30 (estimate based on a 70% reduction in prey availability [4]), Pedjari conservation area in Benin from 80 to 50 [5] and Waza NP in Cameroon from 100 to 50 lions [6] (Fig. 2).

Lion population trends in four National Parks.

3.1 Causes of decline

Biodiversity loss is believed to be a general and ongoing regional trend, associated with human expansion because of demographic growth. In fact, most Protected Areas were originally created in areas with abundant wildlife due to the absence of man caused by river blindness and sleeping sickness, but pressure on those areas only started when the epidemics were controlled and humans expanded [7].

The main economic activity in the Sahel and Sudan vegetation belts, the largest part of the regional extent of occurrence, is extensive animal husbandry. This is mainly practised in a (semi-)nomadic way, over large ranges [8]. Human lion conflict is therefore a widespread problem with a long history. Herdsmen generally accept livestock depredation up to a varying threshold, lion poaching or poisoning is not immediately practised (pers. obs.). Gradually, however, lions have progressively been restricted to protected areas and their surroundings only. Poaching and poisoning has probably been the main direct cause, but in a context indirect human impact (on prey and on habitat).

Lion populations inside protected areas also appear to be declining. One important cause could be the regional economic crisis. The number of civil servants and their salaries decreased substantially as a result of the Structural Adjustment Program that was adopted for economic recovery. The effects on the management of National Parks have been negative, the presence of guards has considerably reduced, especially in the remote areas. The number of guards in Waza NP, for example, dropped from 19 in 1997 to 8 in 2001 (Saleh, pers. comm.). Road maintenance, surveillance, infrastructure maintenance and tourist accommodations have all suffered from budget reductions. In many areas, authorities faced with a lack of capacity for ‘repressive’ management shifted towards ‘participatory’ management in various forms [9,10]. Since the lion is a species with high propensity for conflict with local people, its conservation in protected areas in West and Central Africa under participatory management is not easy.

3.2 Current threats

The main direct threats mentioned during a regional workshop were [11]:

- • poaching/poisoning for livestock protection,

- • poaching/poisoning for commercial/traditional use of lion organs,

- • habitat destruction,

- • livestock encroachment,

- • risks inherent to small populations (inbreeding, stochasticity, etc.).

In addition, most countries allow safari hunting. This paper is not intended to contribute to any of the current debates on lion hunting. We observe, however, that the low figures presented suggest that sustainable offtake is hardly possible. It could therefore be mentioned as a threat.

Risks associated with small populations are probably an important theme for research and management in the near future. However, no systematic inventory of genetic diversity or veterinary survey has been published so far. Therefore, we cannot give any details, and the next section will focus on the other main threat.

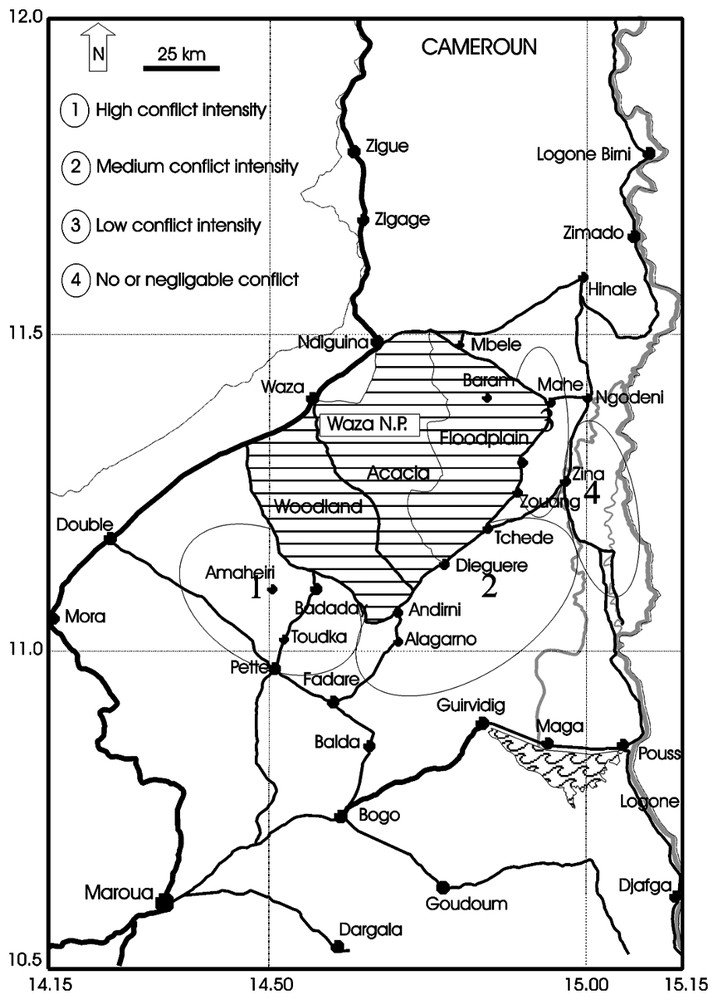

3.3 Human lion conflict

Human lion conflict is generally recognised as a regional management problem, some information is available on the Guinea, Senegal and Benin [11], but the most detailed study was undertaken in Waza NP, Cameroon. Here, predation on livestock is a serious phenomenon, especially to the south of the park. The situation was first assessed with the aid of Participatory Rural Appraisal techniques in 1995 [12] (Fig. 3). More quantitative information was gathered with structured interviews in 1998. These showed that lions are responsible for more damage than any other carnivore, it is estimated that 700 cattle and over 1000 small stock are attacked annually (not necessarily killed and consumed), valued at approximately US$ 140 000. The number of domestic animals killed by all carnivores together equals the mortality due to animal disease, it is estimated that livestock is the main prey for between 20 and 30 lions [13]. These figures obviously suffer from bias (people may exaggerate), but whatever the ‘real’ figures are, they are impressive.

Human lion conflict assessment in Waza NP, Cameroon (from Bauer, 2001).

People in all settlements gave similar information about the locations and moments at which predation occurred. Lions attack all species of domestic animals on the pastures at daytime. People know that lions also hunt at night, but livestock is then kept in enclosures inside the villages where lions hardly ever venture. Hyenas are exclusively nocturnal, they attack small stock in or near the settlements at night. They enter enclosures and even houses, but are easily chased away if the owner is awake. All forms of predation were said to occur more often in the rainy season, because the grass is tall and the rain makes noise which makes stalking easier. This is contrary to experiences in east Africa [14].

Some management options for human lion conflict mitigation were described by Stander [15]. An instrument which has not been described in literature is to chase lions away with the use of repellents. To our knowledge, this technique is generally considered effective in elephant damage mitigation but not used on lions, except in Guinea. The Guinean experience has not been described in any publication (Oulare, pers. com.). The Haut Niger NP park (central Guinea) consists of a core area for strict conservation and a buffer zone which is managed jointly by the state and the local population. Lions were extinct, but an estimated seven individuals re-invaded the area in 1997 and attacked 168 cattle in 1997 and 1998 according to local authorities. The well organised traditional hunters' fraternity decided to apply an ancient technique, in collaboration with the authorities, aimed at chasing the lions into the park's core area. This is done by at least 40 traditional hunters who walk in parallel lines towards the park over approximately 30 km during three or four days, about 100 m between them. While marching, they blow whistles and they each fire one or two blank shots a day, using a muzzle loader with a mixture of three powders: phosphorous nitrate and dried fibre of Trema guineensis and Authonata crassifolia. This produces a lot of noise and an irritating and pervasive smoke. This is repeated on several sides of the core area, whenever necessary. It has led to a reduction in cattle attacks to 6 cases between 1998 and 2000, according to local authorities. This experience is based on traditional knowledge and has not been verified, but it could inspire the development of new conflict mitigation techniques.

4 Conclusion

It is surprising that so much effort has been invested in lion research in Southern and Eastern Africa, while so little is known about lions in West and Central Africa. This is not justified by conservation priority: lions are certainly more threatened in West and Central Africa. At this moment, there are hardly any special research, training or conservation programs for lions, and large conservation organisations still do not give priority to carnivore conservation.

The African Lion Working Group was aware of this situation and defined information gathering on West and Central African populations as a priority [16]. So far, this has led to a process that gives a promising prospect. The publication of the workshop proceedings [11] was given much media attention, awareness is now much higher in conservation circles. In addition, a West and Central Lion Network was created, with the following vision: to promote the long term conservation of lion populations across West and Central Africa and to promote management aimed at maintaining long term viability while reducing human-lion conflict and in a way that contributes to the sustainable development of the region.

Based on the current threats as cited above, research needs and priorities can be defined as:

- • systematic regional inventories of lion numbers, trends, genetic variability, health, prey base and human lion conflicts,

- • biological research on small population viability,

- • animal production research on systems to minimize predator damage to livestock,

- • socio-economic research on the actors involved in poaching and the trade in lion organs,

- • interdisciplinary research on Protected Area effectiveness.

This research agenda is somewhat different from the current East and Southern African agenda, currently focussing on two themes. These are epidemiological research into Tuberculosis, Canine Distemper and Feline Immunodeficiency Virus (FIV or ‘cat-aids’) and ecological research into the demographic and behavioural effects of selective off-take for safari hunting. Human lion conflict is also being investigated, but it does not appear to be the main theme, which is exactly what we propose for the West and Central African lion research agenda.

Acknowledgements

The inventory is based on the kind cooperation of our sources as listed in the table. We acknowledge the assistance of (alphabetically) J. Blanc, G.H. Boakye, G. Chapron, W.T. de Groot, P. Jackson, S. van der Merwe, J. Naude, E.M. de Roos, H.A. Udo de Haes, U.S. Seal, and M. van t'Zelfde. The following institutions contributed in various ways to the process of information gathering: Cameroon Ministry for Environment and Forests, African Lion Working Group, Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, Leiden University, Foundation Dutch Zoos Help, Dutch branch of WWF, Garoua Wildlife School and IUCN regional office for Central Africa.