Version française abrégée

Les mécanismes de l'isolement reproducteur et de la spéciation restent peu documentés chez les organismes marins. L'étude génétique d'espèces sympatriques morphologiquement et écologiquement très proches permet d'aborder cette question fondamentale. Un modèle intéressant est l'anchois européen (Engraulis encrasicolus), chez lequel deux formes distinctes ont été récemment reconnues en Méditerranée, ceci à partir de données morphologiques et génétiques. Une de ces formes occupe l'habitat côtier dans le golfe du Lion et le Nord de l'Adriatique, tandis que l'autre forme, océanique, est présente au large des côtes de l'Atlantique nord-est, de la Méditerranée occidentale, de la mer Adriatique centrale et méridionale, ainsi que de la mer Ionienne. Des différences significatives de fréquences des allozymes et des haplotypes mitochondriaux ont été observées entre les deux formes, suggérant un fort degré d'isolement reproducteur entre celles-ci. Ainsi, l'hypothèse de deux espèces biologiques distinctes chez l'anchois de Méditerranée a-t-elle été émise. Des données indépendantes à des locus nucléaires non codants permettent de tester cette hypothèse. Ici sont présentées les données de fréquences alléliques de deux de ces marqueurs, deux introns, présentant un polymorphisme de longueur. Nos résultats apportent une distinction génétique supplémentaire entre les deux formes d'anchois méditerranéen, confirmant ainsi que le flux génique entre ces dernières est restreint.

Des échantillons d'anchois côtiers ont été capturés dans la baie du Cul-de-Beauduc en Camargue (janvier 2001 ; 43°24′N, 03°35′E) et dans la lagune de Mauguio dans le Gard (mai 2001 ; 43°36′N, 04°04′E). Des anchois océaniques ont été capturés sur l'upwelling de Benguela au large de l'Afrique du Sud (septembre 2000 ; ∼32°10′S, ∼17°30′E) et dans le golfe du Lion au large de Sète (décembre 2000 ; 43°20′N, 04°00′E). Un échantillon supplémentaire provenait du marché aux poissons de Rabat, au Maroc (février 2001). Pour l'analyse génétique des individus de chaque échantillon, des paires d'amorces oligonucléotidiques ont été choisies dans les exons de gènes après alignements de séquences homologues de poissons de familles différentes, de façon à amplifier, par la réaction de polymérisation cyclique (PCR) des introns en position homologue chez l'anchois. Nous avons ainsi dessiné les amorces de trois introns du gène de l'hormone de croissance (locus GH1, GH2, GH3 ci-après), un intron du gène de la somatolactine (SomLac2) et a priori le sixième intron du gène de la créatine-kinase (CK6). Après amplification par PCR, les allèles de longueur ont été séparés par électrophorèse sur gel de polyacrylamide vertical. Lors de tests préliminaires portant sur 5 à 10 individus de chacun des échantillons de Sète et du Cul-de-Beauduc, un polymorphisme de longueur a été observé à deux locus CK6 (CK6-1, CK6-2). Les autres locus testés étaient, soit monomorphes (l'un de deux locus GH1, GH2, SomLac2), soit insuffisamment polymorphes (l'un de deux locus GH3), soit de lecture difficile sur les gels (second locus GH3). Afin de caractériser morphologiquement les deux formes, côtière et océanique, de l'anchois de Méditerranée occidentale, nous avons mesuré les six caractères suivants : rapport de la longueur de la tête sur la hauteur de la tête, nombre d'épines et de rayons branchus sur les nageoires dorsale et anale, et nombre de branchiospines. Ces caractères sont utilisés pour distinguer entre elles différentes espèces du au sein de la famille des Engraulididae. Les mesures ont été faites sur un échantillon de référence du golfe du Lion, comprenant 42 individus d'anchois « blanc » ou côtier et 44 individus d'anchois « bleu » ou océanique.

Des différences très significatives dans les fréquences alléliques aux locus CK6-1 et CK6-2 ont été observées entre échantillons d'anchois côtiers et océaniques ( de Weir et Cockerham compris entre 0,397 et 0,586), alors que les différences géographiques entre populations de la forme océanique étaient faibles à l'échelle de l'Atlantique oriental et de la Méditerranée ( à 0,042). L'absence de différences génétiques significatives entre populations d'anchois océaniques éloignées de plusieurs milliers de kilomètres l'une de l'autre implique des flux géniques très élevés. À l'inverse, une restriction importante du flux génique est déduite des différences de fréquences alléliques entre échantillons d'anchois côtiers et océaniques prélevés à seulement quelques dizaines de kilomètres les uns des autres. Ceci confirme l'hypothèse, émise antérieurement à partir des données allozymiques, de l'isolement reproducteur entre les anchois océaniques et côtiers. Si les différences de fréquences alléliques au locus CK6-1 sont du même ordre que celles aux locus enzymatiques (c'est-à-dire faibles, mais significatives), celles au locus CK6-2 sont quant à elles très nettes, ce qui était déjà le cas des ADN mitochondriaux en Adriatique. Aucun des locus analysés pour l'instant chez l'anchois européen, qu'il s'agisse des locus enzymatiques, des locus introniques, ou de l'ADN mitochondrial, n'est diagnostique entre E. albidus et E. encrasicolus. Ceci laisse ouverte la possibilité que l'isolement reproducteur entre les deux espèces ne soit que partiel, ce qui ne met nullement en cause l'hypothèse de deux espèces biologiques. Une analyse en composantes principales réalisée sur six caractères morphométriques sépare sans ambiguïté les deux espèces. Les échantillons de spécimens des deux espèces diffèrent de façon significative par la morphologie de la tête, le nombre d'épines des nageoires dorsale et anale, ainsi que le nombre de branchiospines.

Que deux espèces puissent ainsi être distinguées chez l'anchois européen, poisson dont la biologie et l'écologie avaient pourtant fait l'objet de nombreux travaux du fait de son intérêt halieutique, appelle à un approfondissement de nos connaissances quant à la systématique, l'écologie et l'évolution des Engraulididae en général. La mise en évidence d'espèces cryptiques a aussi des implications sur la gestion future des pêcheries, non seulement en Méditerranée, mais aussi partout dans le monde où l'on a détecté la présence sympatrique de deux formes, côtière et océanique, de l'anchois. Nous proposons le maintien du nom scientifique Engraulis encrasicolus Linné, 1758 pour la forme océanique de l'anchois européen et proposons le nom Engraulis albidus sp. nov. ( « anchois blanc ») pour l'anchois côtier de Méditerranée (golfe du Lion, Adriatique nord).

1 Introduction

Animals inhabiting the marine pelagic environment generally have broad distribution ranges, very large population sizes, and high potential for dispersal, which provide little opportunity for allopatric speciation. The mechanisms of their genetic differentiation, reproductive isolation, and speciation are poorly documented [1]. A way of approaching the fundamental question of speciation in marine organisms is to investigate the population genetics of morphologically and ecologically similar species that share a part of their range [1,2]. There are few known examples of cryptic diversity among species in the pelagic environment [2], but molecular studies have provided one such possible example in an oceanic mesopelagic fish [3] and hinted at some form of reproductive segregation between populations of European eel [4]. The hypothesis of cryptic species has also been recently proposed for European anchovy Engraulis encrasicolus [5].

Anchovies certainly are among the most common coastal pelagic fishes. They support the largest fisheries in the world with millions of tons harvested annually [6]. The geographic range of European anchovy, once thought to be confined to the coastal northeastern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean–Black Sea, is now believed to probably extend all along the coast of western to southern Africa and a portion of the Indian Ocean [7,8]. Mitochondrial (mt)-DNA sequences effectively confirmed this by showing that South African anchovy (formerly E. capensis, which is also present in the western Indian Ocean) very recently derived from an E. encrasicolus population from northeastern Atlantic or Mediterranean [8]. Two forms have nowadays been identified within E. encrasicolus in Europe, on the basis of morphology [9] and genetics (review in [5]). Anchovies of the first form, coined Group I, occupy the inshore habitat of the ‘Golfe du Lion’ (northwestern Mediterranean Sea) and the northern Adriatic Sea, while Group-II anchovies are found offshore in the oceanic waters of the Biscay Gulf in the northeastern Atlantic, the western Mediterranean, and the central/southern Adriatic Sea and the Ionian Sea in the eastern Mediterranean [5]. The distinction between the two Groups originally derived from the observation of small but consistent allozyme frequency differences between populations from different habitats, without relationship to geographic distance. Stronger mtDNA haplotype-frequency differences were observed when comparing the respective frequencies of mtDNA clades A and B [10] in the two groups. However, mtDNA data for Group I are still scarce and neither A or B haplotypes were fixed in any of the Group-I or Group-II populations surveyed so far [5,8,10]. While the allozymic, morphometric, and mitochondrial DNA data altogether strongly suggest that Group-I and Group-II anchovies are two biological species, independent non-coding nuclear-DNA data were needed to confirm this hypothesis. Here we report on two intronic nuclear-DNA loci that further distinguish from one the other the populations from inshore and oceanic habitats and provide compelling evidence of a barrier to neutral nuclear gene flow between them, thus confirming their status as distinct, biological species. In addition, morphometric data that discriminate between reference samples of the two species are provided.

2 Materials and methods

Inshore anchovies were sampled by pelagic trawling on 3 January 2001 in Cul-de-Beauduc, a shallow cove located in Camargue, southern France (43°24′N, 04°35′E). Other inshore anchovies were captured using networks of nets and traps set on the bottom of the Mauguio lagoon, southern France (43°36′N, 04°04′E) in May 2001. Anchovy from oceanic (‘offshore’) habitats included samples caught by pelagic trawling 18 nautical miles off Sète, in the ‘Golfe du Lion’, northwestern Mediterranean Sea (43°10′N, 04°00′E) in December 2000, and from experimental fishing operations by the South African government's agency for marine and coastal management (M&CM) on the Benguela upwelling off South Africa (∼32°10′S, ∼17°30′E) in September 2000. An additional sample, of unknown precise origin, consisted of 15 anchovies purchased from the fish market in Rabat, Atlantic coast of Morocco, in February 2001. The inshore and offshore sampling localities in the northwestern Mediterranean were distant from one the other by ca. 30 to 40 nautical miles (= ca. 50–70 km).

To characterize the two forms (that is, coastal and oceanic, respectively) of anchovy in the northwestern Mediterranean, two morphometric and five meristic characters were measured and counted on reference samples of individuals: head depth, head length, apparent number of dorsal-fin spines, number of dorsal-fin rays, apparent number of anal-fin spines, number of anal-fin rays, and number of gillrakers on first lower-gill arch. The foregoing morphometric characters and meristic counts have been used for the distinction of species within the family Engraulididae [6]. Counts of fin spines and rays and of gillrakers were done under a stereo zoom microscope. We are aware that the first dorsal- and anal-fin spines may be difficult to detect from simple examination under a zoom microscope, because these may be hidden to the observer when they are too tiny and embedded in the flesh (R. Rodríguez-Sánchez, personal communication). Differences in counts of fin spines reported in the present study (see results) nevertheless reflect differences in their size and/or morphology. Measurements of head depth, head length, and standard length were made to the nearest 0.1 mm using a Vernier caliper. Head depth was measured perpendicular to the main axis of the body at the rear extremity of the opercle; head length was measured from tip of snout to rear extremity of opercle. The ratio of head depth to head length was normalised using an arcsine-transformation. The reference samples included 42 randomly chosen individuals of coastal anchovy (including paratypes MNHN 2002-1718 to 1726), all from Cul-de-Beauduc in the ‘Golfe du Lion’, and 44 randomly chosen individuals of oceanic anchovy (including voucher specimens MNHN 2002-1776 to 1805), all from Sète in the ‘Golfe du Lion’. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done on the matrix of individuals x characters using the Ade-4 software [11]. The statistical significance of the output of PCA was tested by permutations using Procedure Discriminant analysis/Test implemented in Ade-4. Discriminant analysis [11] was also run on the same dataset.

Anchovy samples from five localities (details on sampling locations and sample sizes in Table 1) were genetically analysed at six intron loci. Exonic primer pairs were designed to specifically amplify introns 1, 2, and 3 of the growth hormone gene (hereafter designated as GH1, GH2 and GH3) and intron 2 of the somatolactin gene (SomLac2), using polymerase chain reaction (PCR), from the alignment of homologous nucleotide sequences in fishes (GenBank: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The complete sequence of Lates calcarifer growth hormon gene (GenBank U16816) was aligned with cDNA sequences of Lates calcarifer (GenBank X59378), Thunnus sp. (GenBank X06735), Sciaenops ocellatus (GenBank AF065165) and Lateolabrax japonicus (GenBank L43629) to locate introns and select conserved exon regions for PCR-priming. The three primer pairs we designed for loci GH1, GH2 and GH3 respectively were: GH1-F (5′-GAAYCCAGACCAGCCATGGAC-3′) and GH1-R (5′-GCGAGCAGGTGGAGGTGTTG-3′), GH2-F (5′-CAACACCTCCACCTGCTCGC-3′) and GH2-R (5′-CCTGCAGGAAGATTTTGTTG-3′), and GH3-F (5′-CCCSATYGACAAGCAYGAGAC-3′) and GH3-R (5′-GAYTCKACCAATCGATASGAG-3′). For the somatolactin gene, primers SomLac2-F (5′-ARGARAAACTTCTRGACCGRG-3′) and SomLac2-R (5′-ACCCACTTGGTYTTGTTGAG-3′) were designed from the alignment of partial genomic sequence of Oncorhynchus keta (GenBank D10638) with cDNA sequences of Siganus guttatus (GenBank AB026186), Dicentrarchus labrax (GenBank AJ277390), Paralichthys olivaceus (GenBank M33695, M33696), Sparus aurata (GenBank L49205), Hippoglossus hippoglossus (GenBank L02117), Cyclopterus lumpus (GenBank L02118), Tetraodon miurus (GenBank AF253066) and Gadus morhua (GenBank D10639). Primers CK6F (5′-GACCACCTCCGAGTCATCTC-3′) and CK7R (5′-CAGGTGCTCGTTCCACATGA-3′) [13], which are derived from, respectively, primers CK6-5′ and CK7-3′ [14], were used to specifically amplify Intron 6 of creatine kinase genes (CK6), actually a multigenic family.

Engraulis spp. Allele frequencies at two nuclear-DNA loci in five samples from the eastern Atlantic and the northwestern Mediterranean. Benguela, Benguela upwelling off Cape Peninsula, South Africa, September 2000; Rabat, Rabat fish market, Morocco, February 2001; Sète, 18 miles offshore, ‘Golfe du Lion’, northern western Mediterranean, December 2000; Cul-de-Beauduc, inshore, shallow bay in the Camargue region, northern Western Mediterranean, January 2001; Mauguio, Mauguio lagoon, northern Western Mediterranean, May 2001. N, sample size; , Weir and Cockerham's estimate of the correlation of alleles within individuals relative to the population [12]

| Locus, allele | Sample | ||||

| Benguela | Rabat | Sète | Cul-de-Beauduc | Mauguio | |

| CK6-1 | |||||

| 095 | – | 0.03 | 0.03 | – | – |

| 098 | – | – | – | 0.02 | – |

| 100 | 0.70 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.97 | 1.00 |

| 102 | – | – | 0.03 | – | – |

| 103 | – | – | 0.08 | – | – |

| 113 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.02 | – |

| 115 | 0.05 | – | – | – | – |

| (N) | (10) | (15) | (20) | (32) | (9) |

| −0.301 | −0.050 | −0.086 | −0.008 | – | |

| CK6-2 | |||||

| 096 | – | 0.03 | – | – | – |

| 098 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.06 |

| 099 | – | – | – | 0.03 | – |

| 100 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.74 | 0.89 |

| F | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.06 |

| (N) | (10) | (15) | (20) | (31) | (9) |

| 0.265 | 0.314 | −0.128 | −0.211 | −0.032 |

For each individual, a piece of macerated muscle was DNA-extracted using a classical phenol-chloroform protocol, and the DNA used as template for PCR. Just before the PCR, the forward primer was radioactively labelled by incubating for 30 min at 37 °C a mixture of 2 μM primer, 1 U T4 polynucleotide-kinase (Eurogentec, Liège, Belgium), and 1.7 μM (0.05 mCi) [γ-33P]ATP (Isotopchim, Ganagobie, France). Ten microlitres of reaction mixture comprising 4 μl DNA solution, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 74 μM each dNTP, 0.4 μM reverse primer, 0.1 μM radioactively labelled forward primer, and 0.4 U Taq polymerase (Promega, Madison WI, USA) in its buffer, was subjected to 35 cycles of DNA denaturing (12 s at 94 °C), annealing (12 s at 52 °C) and elongating (30 s at 72 °C), followed by a final elongation step of 5 min at 72 °C. The PCR product was mixed with an equal volume of 95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA, 10 mM NaOH, 0.05% xylene cyanol and 0.05% bromophenol blue, and heat (95 °C)-denatured. Size-polymorphism was assessed by subjecting the denatured PCR product to electrophoresis in 0.4-mm-thick polyacrylamide gel with 5% acrylamide and 42% urea. After migration, at 50 W for 5 h, the gel was dried at 80 °C for 1 h in a vacuum drier and exposed against X-Omat autoradiographic film (Eastman-Kodak, Rochester NY, USA) for 12 h or more, depending on the level of radiation. Preliminary tests of polymorphism were conducted on 5–10 randomly chosen individuals from both Cul-de-Beauduc and Sète samples. PCR products from heterozygous individuals at both CK6 loci were excised from polyacrylamide gel. The excised piece of gel was put in 10 μl water in a microtube and subjected to two cycles of freezing/melting/vortex and centrifugation. The supernatant was used as template for non-radioactive PCR. The reamplified products were then purified using the PCR Product Pre-Sequencing kit of USB Corporation (Cleveland OH, USA) and sequenced.

Correlations of alleles within individuals relative to the population, and those within populations relative to the total population, were estimated using estimators and [12], respectively. To give the expected distributions of and under the null hypotheses and , respectively, 1000 pseudo-matrices of individuals x genotypes were generated from the original matrix by random permutations of alleles at a locus (for testing -values) and of individuals (for testing -values). The probability of occurrence of a parameter value larger or equal to the estimate was evaluated at , where n is the number of pseudo-values larger than or equal to the estimate and N is the number of random permutations [15]. The null hypothesis was rejected when (using a two-tailed test). The null hypothesis was rejected when (using a one-tailed test). The estimations of f and θ and permutation tests were made using Procedure Fstats in the computer package Genetix [16].

3 Results

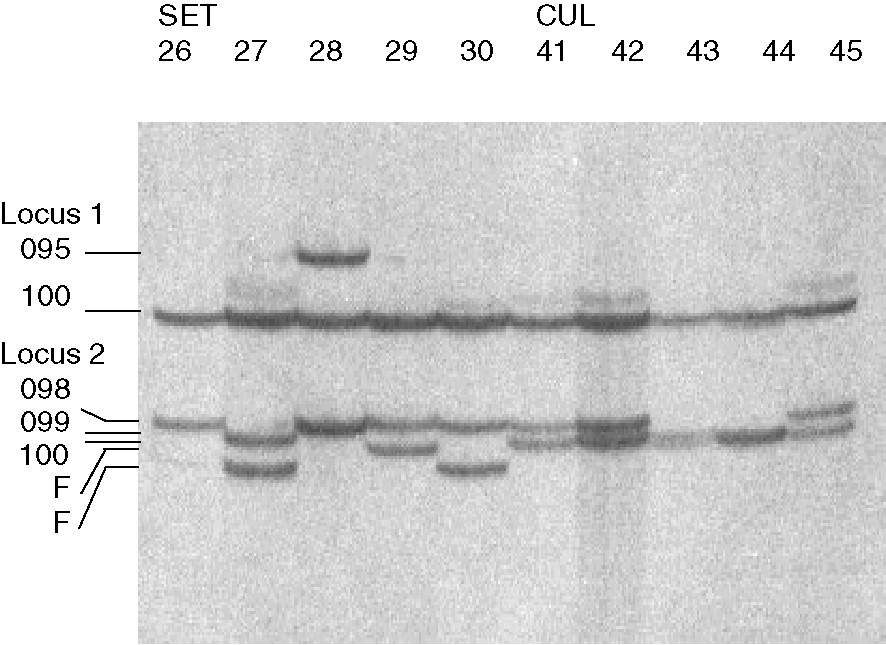

Two loci, hereafter designated CK6-1 and -2, were scored using the CK6F/CK7R primer pair, supposed to amplify Intron 6 of creatine-kinase genes. These exhibited size polymorphism on 5% polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 1). The other loci tested exhibited either sample monomorphism (one of two GH1 loci, GH2, SomLac2), insufficient polymorphism (one of two GH3 loci), or were difficult to score (the other GH3 locus). Five anchovy samples ( individuals in total) were then screened at loci CK6-1 and -2. Because of insufficient resolution, shorter alleles at locus CK6-2 were pooled into compound allele F. Inferred genotype frequencies were compatible with Mendelian genetic determination [test of Hardy–Weinberg genotypic proportions: average fixation index over loci and samples, , not significant (see also Table 1)]. Two size-alleles at locus CK6-1 (102, 113) and three size-alleles at locus CK6-2 (098 twice, 100, F) were sequenced in both forward and reverse directions. All 6 sequences (GenBank accession Nos. AY486342 to AY486347) were aligned using BioEdit [17]. The difference in size between size-alleles 102 and 113 at locus CK6-1 was mainly due to a short transposon-like insertion/deletion (indel). The indel was 116 bp long and possessed at its 3′ end a 8-bp short sequence (5′-TACAATGA-3′) that flanks its 5′ end in allele 102. Differences in size between alleles at locus CK6-2 were caused by shorter (1–21 bp) indels. Two locus-specific primer pairs were designed from the sequences. Specific to locus CK6-1 are forward CK6-1F (5′-CGACATTGTAATGATGTTACAATGA-3′) and reverse CK6-1R (5′-ATTTCCTTTGGGTTGGCTCTTCTCT-3′) primers (annealing temperature = 54 °C); specific to locus CK6-2 are forward CK6-2F (5′-CTCAGAACTACATACCAAACCAATG-3′) and reverse CK6-2R (5′-ACTCACTGTAATTCTGAATAGAGCT-3′) primers (annealing temperature = 52 °C). In PCR amplifications of a subsample of individuals, using these novel primer pairs, allele-size polymorphism at each locus was consistent with a Mendelian model of inheritance (data not shown). This confirmed the interpretations of gels loaded with the multiplex products from CK6-F/CK7-R-primed PCRs. Significant -values were observed in all comparisons between oceanic anchovies and inshore anchovies; no significant -value was found for the other pairwise comparisons (Table 2).

Engraulis spp. PCR amplification using primers CK6F and CK7R [13]. Autoradiography of PCR products after electrophoretic migration in vertical denaturing polyacrylamide gel of reference individuals SET 26–30 from sample Sète and CUL 41–45 from sample Cul-de-Beauduc, and designation of alleles at loci CK6-1 (Locus 1) and CK6-2 (Locus 2).

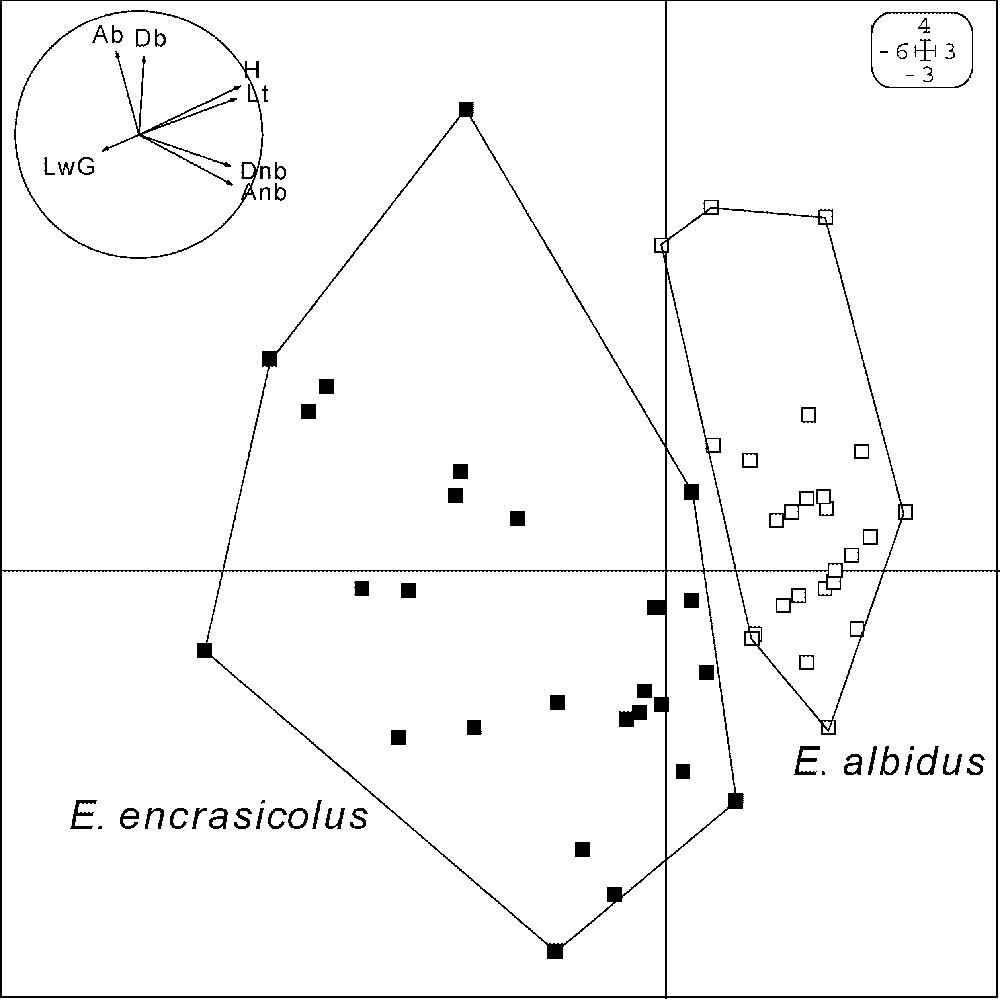

No significant effect of body size (standard length) on the ratio of head depth to head length was noted in sample Cul-de-Beauduc (; 40 d.f.), but such a trend was apparent in the Sète sample (; 42 d.f.; ). The samples of specimens of the two species significantly differed by head morphology, numbers of anal- and dorsal-fin spines, and number of gillrakers on first lower-gill arch (Table 3). Principal component analysis, performed on the matrix of individuals defined by two morphometric measurements and five meristic counts, unambiguously separated the two samples as defined by their origin, i.e. coastal anchovy from Cul-de-Beauduc vs. oceanic anchovy from off Sète (Fig. 2). Permutation tests confirmed the statistical significance of this grouping (procedure Discriminant analysis/Test of Ade-4 [11]: 10,000 permutations of individuals in the original data matrix; ). Discriminant analysis [11] also produced the linear function of morphometric and meristic variables that most differentiates the two groups shown by PCA (see legend to Fig. 2).

Engraulis albidus sp. nov. and E. encrasicolus: mean ± SD for six morphometric and meristic characters in two reference samples (Cul-de-Beauduc for E. albidus, Sète for E. encrasicolus). H/Lt, ratio of depth of head to length of head; Dnb, number of dorsal-fin spines; Db, number of dorsal-fin rays; Anb, number of anal-fin spines; Ab, number of anal-fin rays; LwG, number of gillrakers on first lower-gill arch. P, probability of value greater than or equal to the observed difference under the null hypothesis of equality of means (Student's t-test [5])

| Character | E. albidus | E. encrasicolus | t-test | ||

| mean ± SD | (N) | mean ± SD | (N) | ||

| 0.85±0.03 | (42) | 0.82±0.03 | (44) | P<0.001 | |

| Dnb | 3.00±0.00 | (29) | 2.70±0.46 | (27) | P=0.001 |

| Db | 12.28±0.83 | (29) | 12.19±0.82 | (27) | P=0.687 |

| Anb | 2.90±0.30 | (29) | 2.57±0.50 | (30) | P=0.004 |

| Ab | 15.21±0.96 | (29) | 15.27±1.39 | (30) | P=0.851 |

| LwG | 34.52±1.59 | (29) | 35.67±1.90 | (30) | P=0.016 |

Engraulis albidus sp. nov. and E. encrasicolus. Principal component analysis (output from Ade-4 [11]): annotated scores for components 1 (horizontal; 36.0% of total inertia) and 2 (vertical; 19.0% of total inertia) of individuals of two reference samples (respectively, Cul-de-Beauduc and Sète), characterised by two morphometric measurements and five meristic counts. Ab, number of anal-fin rays; Anb, number of anal-fin spines; Db, number of dorsal-fin rays; Dnb, number of dorsal-fin spines; H, ratio of depth of head to standard length (-transformed); Lt, ratio of length of head to standard length (-transformed); LwG, number of gillrakers on first lower-gill arch. The first discriminant equation [11] derived from the same dataset was , where SL is standard length.

4 Discussion

Highly significant -values were observed in all comparisons between oceanic anchovies and inshore anchovies, while no significant differences were detected among samples within either oceanic or inshore anchovies. The lack of detectable genetic differences across vast distances (several thousand kilometres) within a Group implies high levels of intragroup gene flow. By contrast, considerable restriction in nuclear gene flow was demonstrated between Group-I and Group-II anchovies at very short distance (a few tens of kilometres). This is a confirmation of the hypothesis, raised previously from allozymes [5], that Group-I (coastal) and Group-II (oceanic) anchovies are reproductively isolated. In short, these should be considered as distinct, biological species. Allele-frequency differences between the two species at locus CK6-1 were of the same order as those at allozyme loci [5]. Those at locus CK6-2 were much stronger, of the same order as haplotype-frequency differences between the two species in the Adriatic Sea [5]. Persistent genetic differences, at neutral genetic markers, between coastal and oceanic forms of European anchovy imply that hybrids, if any, are likely at disadvantage. This effectively demonstrates the ecological specialisation of each form. However, the fact that no diagnostic locus has so far been found between the two species leaves open the possibility that reproductive isolation may only be partial. This does not mean that the hypothesis of two biological species in European anchovies should be questioned: in the case of partial reproductive isolation such as that observed in hybrid zones, introgression rates at neutral markers are expected to vary according to their physical linkage with speciation genes [18,19].

That cryptic species were found in European anchovy, a fish whose biology and ecology have received much attention because of its interest to fisheries [9,10,20,21], hints that species richness in the family Engraulididae may be higher than currently thought [7]. This in turn calls to further studies on the systematics, ecology and evolution of anchovies. For instance, two distinct reproductive strategies have been recognized in Japanese anchovy (Engraulis japonicus) in relation with their habitat, distinguishing an inshore population from an offshore population [22]. Likewise, both coastal and oceanic spawning areas have been reported for Engraulis encrasicolus in the Gulf of Biscay [23]. If this is a stable feature of anchovy populations in this region, then distinct, perhaps reproductively isolated, spawning populations could have thus been detected. At the other extreme of the geographical range of the European anchovy, the spawning grounds of Azov Sea anchovy are geographically separate and ecologically distinct from those of Black Sea anchovy (both currently E. encrasicolus), whereas both populations winter in the Black Sea [24]. Investigating population genetic structure in these model systems may further reveal some degree of reproductive isolation between oceanic and coastal populations. The present results for Atlantic/Mediterranean E. encrasicolus warrant further genetic studies of Japanese, Gulf of Biscay, and Black Sea anchovy populations and of other similar systems in the marine pelagic environment.

5 Systematics and distribution

5.1 Engraulis encrasicolus Linnaeus, 1758

No type is known for this species [25] and Linnaeus' original description [26] is too vague to allow the distinction between the two species referred to here (which are also Groups I and II of [5]). For the sake of stability, we propose to arbitrarily maintain the specific name encrasicolus to the apparently most common and widespread anchovy species in the seas of Europe, that is Group-II anchovy [5], also referred to as “oceanic” or “open-sea” anchovy [5, present work], and “blue anchovy” by fishermen in the ‘Golfe du Lion’ and in the Adriatic Sea [9]. In the following, the term E. encrasicolus sensu lato (s.l.) will be used to designate all European anchovies without distinction, while the binomen E. encrasicolus will be kept exclusively in accordance with the present revision.

Type and voucher specimens. – Neotype, collected on 14 December 2000, deposited by P. Borsa at the ‘Muséum national d'histoire naturelle’, Paris, on 6 August 2002 (registered as MNHN 2002-1775). Voucher specimens (registered as MNHN 2002-1776 to MNHN 2002-1844) include specimens SET 26–30 of Fig. 1.

Neotype locality. – Eighteen nautical miles (33 km) off Sète in the ‘Golfe du Lion’, northern part of the western Mediterranean.

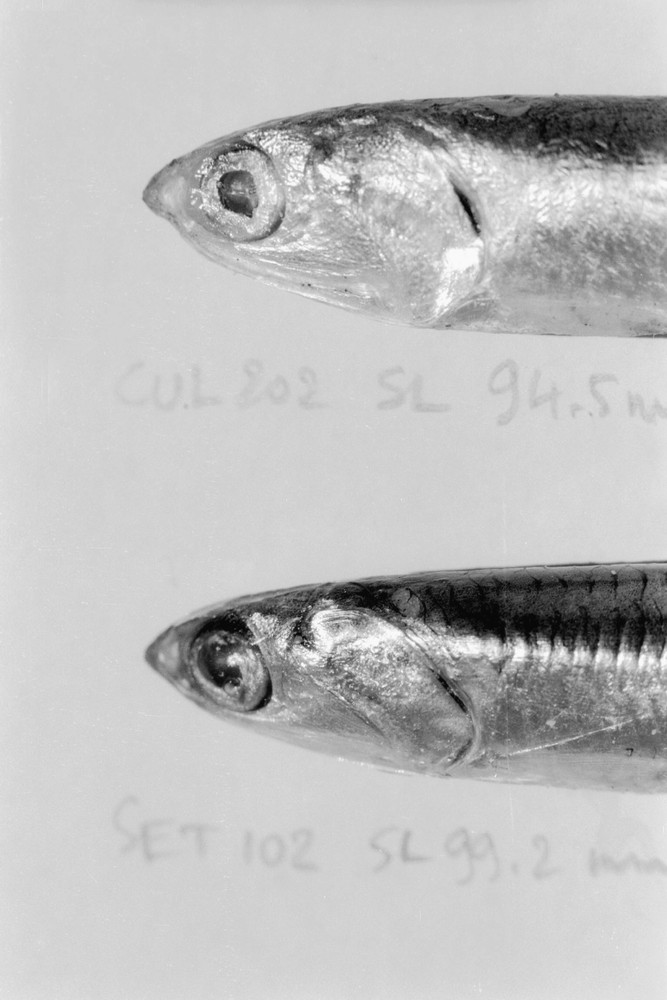

Diagnostic features. – Flanks silvery, belly white, and back blue to dark blue with tones of brown, depending on light conditions (Fig. 3). In the ‘Golfe du Lion’, mean ratio ± standard deviation of head depth (measured perpendicular to the main axis of the body at the extremity of opercle, using a Vernier caliper) to head length (measured from tip of snout to rear extremity of opercle) was (measures from 44 individuals ranging in size from 88.5 to 133.9 mm standard length). The average values for five other characters are given in Table 3. In the northwestern Mediterranean, individuals smaller than 120 mm standard length are sexually immature (Y. Guennegan, B. Liorzou, J.-P. Quignard, personal communication). So far, positively identified from allozyme-frequency data [5,9,20,27,28], mitochondrial-DNA haplogroup-frequency data [5,10], and size-allele frequencies at two creatine-kinase gene intron loci (namely, CK6-1 and CK6-2; present work). In the Golfe du Lion, CK6-1 polymorphic, the most common allele at CK6-2 (098) yields DNA fragment of larger size than the most common allele in E. albidus sp. nov. (Fig. 1; Table 1). The frequency of mitochondrial DNA type A is comprised between 0.40 and 0.50 in the Gulf of Biscay, the northern Western Mediterranean, the Tyrrhenian Sea, and the Ionian Sea, all other haplotypes being of type B [5,10,29]. Frequency of most common electromorph at enzyme locus IDHP-2 <0.65 [5,9].

Above: Engraulis albidus sp. nov. specimen No. CUL 202 (MNHN 2002-1774: paratype) from Cul-de-Beauduc, January 2001, standard length (SL) 94.5 mm; below: E. encrasicolus specimen No. SET 102 from Sète, December 2000, SL 99.2 mm.

Habitat. – Pelagic, oceanic. At salinity > 38 psu and depth > 75 m in the Adriatic Sea [5,9].

Distribution. – Northern part of the western Mediterranean, central and southern Adriatic Sea, Gulf of Biscay, Benguela upwelling. Further genetic studies are necessary to ascertain its presence in other regions in the eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean.

5.2 Engraulis albidus sp. nov.

This name applies to Group I anchovy of [5], also referred to as “inshore” anchovy [5, present work] and “white anchovy” by fishermen in the Golfe du Lion, northwestern Mediterranean (hence the specific name albidus) and “silver anchovy” in the northern Adriatic Sea [9].

Type specimens. – Holotype, collected on 3 January 2001, deposited by P. Borsa at the ‘Muséum national d'histoire naturelle’, Paris, on 6 August 2002 (registered as MNHN 2002-1716). Paratypes (registered as MNHN 2002-1717 to MNHN 2002-1774) include specimens CUL 41–45 of the present work and CUL 202 of Fig. 3.

Type locality. – Cul-de-Beauduc in Camargue, southern France, northwestern Mediterranean.

Diagnostic features. – Large silver stripe along the flank, delineated on the dorsal side by a thin longitudinal dark stripe. Back fleshy to light brown. General aspect paler than that of E. encrasicolus (Fig. 3). In the Golfe du Lion, mean ratio of head depth to head length was (measures from 42 individuals ranging in size from 61.6 to 98.8 mm standard length). The average values for five other characters are given in Table 3. It is morphologically distinct from E. encrasicolus in the Adriatic but no simple diagnostic character has been proposed to date, except raw multivariate scores from canonical analysis on morphomometric measurements collected using a ‘truss network’ [5,9]. Statistically significant morphological differences were found between northern/inshore Adriatic (E. albidus) and central/southern Adriatic (E. encrasicolus) anchovy samples in more than half the univariate tests performed ([9]: parameters and data not explicit). It reaches 8- to 9-cm standard length at sexual maturity. It does not grow larger than 12 cm in the ‘Golfe du Lion’. Its growth is slower than that of E. encrasicolus in the Adriatic Sea [30]. In the northern Adriatic, the frequency of mitochondrial DNA type A is comprised between 0.14 and 0.20, all other haplotypes being of type B [5,10]. In the ‘Golfe du Lion’, allele 100 at locus CK6-1 nearly fixed; most common allele at locus CK6-2 (100) yields DNA fragment of smaller size than most common allele in E. encrasicolus. In both Adriatic Sea and ‘Golfe du Lion’, the frequency of most common electromorph at enzyme locus IDHP-2 is over 0.70 [5].

Habitat. – Pelagic from inshore waters, brackish lagoons, and estuaries in the northwestern Mediterranean. Observed in brackish lagoons from the beginning of spring to the end of summer. Leaves the lagoons in autumn to the nearby coastal marine waters. Presumably spawn in lagoons in the summer (a presumption based on the observation of concentrations of small-sized anchovies together with large densities of eggs in the Thau lagoon, southern France, in July [31] and on the presence of sexually mature individuals of standard length comprised between 8 and 9 cm in the Mauguio and Prevost lagoons, southern France, as early as May (J.-P. Quignard, personal communication)). Living at salinities <38 psu and depths in the northern Adriatic Sea [5,9].

Distribution. – So far, positively identified using allozyme frequency data [5,9,20,27], or size-allele frequencies at two creatine-kinase gene intron loci (namely, locus CK6-1 and locus CK6-2; present work). Shoreline of Camargue in the northwestern Mediterranean Sea; Mauguio, Prevost, and Thau lagoons in southern France; northern Adriatic Sea. These indications on the distribution should be considered as preliminary. The use of genetic markers to search for the presence of E. albidus in other regions where E. encrasicolus s.l. or related species have been reported is warranted.

Acknowledgments

We thank Touryia Atarhouch, Pierre Fréon, Yvon Guennegan, Michel Houny, Jean-Pierre Quignard, and Carl van der Lingen for kindly providing samples; Joseph Baly, Yanis Bouchenak, Isabel Calderón, Jacques Dietrich, and Marie Pascal for participating in the laboratory work, Patrice Pruvost for assistance at MNHN, Stewart Grant, Dominique Ponton, and Rubén Rodríguez-Sánchez for insightful discussions and comments, and François Bonhomme for continued encouragement. This research was funded in part by the following institutions: French Government's CNRS (UMR 5000), IFREMER (URM16) and IRD (UR 081), for laboratory expenses; Republic of South Africa's M&CM for sampling on the Benguela upwelling.