1 Introduction

The interface between the earth and the sea constitutes a region of great diversity at a physical level and at a biological level [1]. Since a long time, the French Atlantic sand-dunes have been used and exploited. Traditionally, land uses consisted in pasture and sand extraction. They have led to important dune degradations. The fixation of the mobile dune by reprofiling, placing fences, planting marram grass and then afforesting was achieved and has permitted to manage sand movements and to reduce dangers [2,3]. Forestry has then became a way to protect but also the only way to manage sand dunes.

Agriculture and afforestation have modified dune landscapes but at the end of the 20th century tourism is the most destructive human activity affecting coastal areas [4–6]. From resources, dunes have became recreational areas. Many sites have been irreversibly transformed with the construction of seaside resorts, including hotels and apartments on the seafront, campsites and golf courses [7,8].

The Atlantic French dunes are in part the reflect of human activities and can't be considered as a completely natural system. Nevertheless they do have a very high ecological and conservative value as they are very original and rare systems. Fixed dunes which present an important biodiversity at the species and the species community levels are considered as a priority habitat by the European habitat directive [9]. Non forested fixed dunes, now reduced to small fragmented areas, must be conserved.

The conservation of fixed dunes vegetation is a complex aim. It first implies to preserve the vegetation from destructive activities and eventually to restore degraded systems. But fixed dunes are also a dynamic stage and must be manage so as to prevent the development of thickets and the establishment of an older stage in the succession.

The Office National des Forêts (O.N.F.) which manages a great surface of French dunes, have been interested in a better knowledge in dunes ecology and has led European programs (LIFE) located on few dunes. The state-owned sand-dune at Quiberon situated in southern Brittany (France) has been chosen to investigate experimentation in conservatory management and restoration ecology. This article describes the main results of the different experiences concerning some disturbances effects and restoration processes.

2 Material and methods

2.1 The study site

The state-owned sand-dune at Quiberon (southern Brittany, France 47°30′N, 3°10′W) consists of a long dune extending on 25 km [10]. Recognised for its great floristic diversity [11] it possesses one of the largest non-forested fixed dune in France which is inhabited by an association of small geographic range: the Roso-Ephedretum (Kühnholtz Lordat 1923) Vanden Berghen 1958 [12]. This site has been the subject of a European program (LIFE) since 1995 and forms part of the Natura 2000 network [9].

2.2 Experimental device

2.2.1 Monitoring

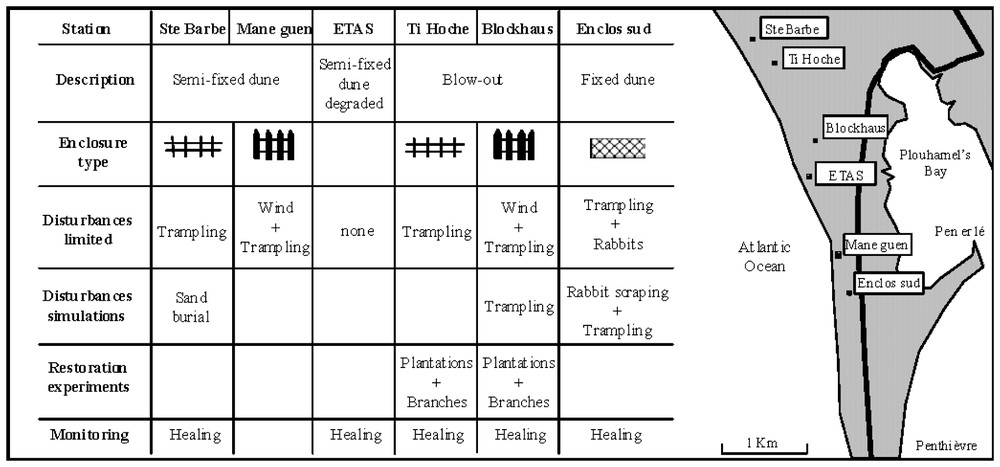

In order to study restoration mechanisms, effects of disturbances and management experiences, six stations have been chosen in the Quiberon sand-dune for their degradation degree, and enclosed in 1996. The Fig. 1 presents the description of the experimental protocol and the monitoring realised on each station.

Description and location of the 6 stations in the sand-dune of Quiberon.

The evolution of the vegetation in homogeneous places has been monitored using permanent lines of 100 points [13]. Transects [14] has been used to study restoration processes in heterogeneous places. Transects consist in contiguous 1 m2 quadrats in which vegetation is recorded using Braun-Blanquet coefficients [15].

2.2.2 Experimentation

Rabbit and wind action were simulated in 9 m2 squares, in which 10 quadrats of 30×30 cm were chosen for monitoring using Latin square method. In order to simulate rabbit scraping vegetation was removed and kept in place or exported. A dressing of sand (6.6 kg/m2) was used to evaluate one of the wind effects.

An experimental trampling was applied on two vegetation communities, a semi-fixed dune and a fixed dune, in May, June and September. The protocol consisted in 4 simulated foot paths 10 m long and 1 m wide, delimitated in an homogeneous area. Four trampling treatments were assigned to each of the four foot paths: a control (no trampling) 75, 150 and 300 passages. The vegetation was monitored using permanent lines located in the centre of each path.

Four methods of blow-out restoration were tested and monitored by the phytosociological method. Carex arenaria and Ammophila arenaria individuals were planted in 5×5 m squares every 50 cm. Cypress or gorse branches were used so as to cover the sand in 9 m2 squares.

3 Results

3.1 Effects of disturbances

The exclosures use, to isolate areas from one of the disturbances, didn't provide important results, since the monitoring period was too short. Artificially made disturbances studies were more informative.

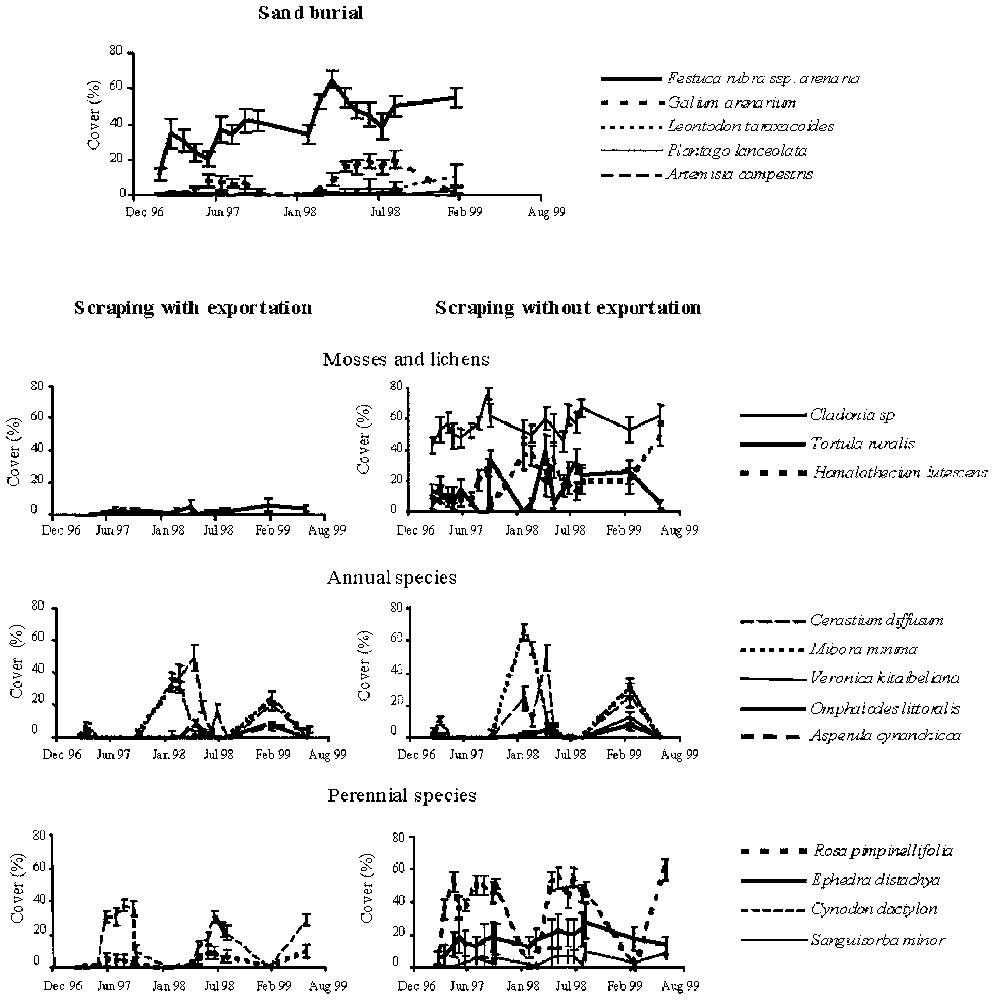

Wind appears to be a factor which limits a lot the floristic composition in the semi-fixed dune. After sand burial, no plant can really resist, but Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria and Galium arenarium possess a good regeneration power (Fig. 2). They permit then other species to develop by stabilizing the substrate.

Evolution of the cover of the principal species after sand burial and in the scraping quadrats with or without exportation of the vegetal material. Means and standard errors.

The analysis of the exclosure effect revealed an important appetite of rabbits for lichens. The opening of the milieu, after scraping, allows a good annuals development and favour Omphalodes littoralis, an endemic species of the French Atlantic shoreline (Fig. 2). The scraping has a positive effect at low level, but it can be detrimental to the specific richness and the cover at a higher intensity (Fig. 2).

Trampling is a complex disturbance as the vegetation response depends on the season (Fig. 3). In particular conditions of intensity and season, this disturbance can benefit to the vegetation cover (Fig. 3).

Evolution of the relative frequency (RF) of the all vegetation one month and one year after a May, July, or September trampling in a semi-fixed and a fixed dune.

3.2 Restoration processes

Restoration mechanisms depends on the state of degradation. An opening of the vegetation regenerates quickly after disturbances (Fig. 4). When the substrate is naked, restoration appears to be very difficult (Fig. 4). This low process is composed of two successional mechanisms. A colonization with seeds at the centre is realized by Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria in wind-exposed situation or by Erodium cicutarium or Leontodon taraxacoides in more protected conditions. Carex arenaria or Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria spreading abroad the hole margins constitute a second type of colonization.

Restoration of the vegetation following the stations protection: comparison of two degrees of degradation. Examples of a transect crossing the station “Enclos sud” and a transect crossing the station “Blockhaus”.

Some techniques of restoration have been tested in fixed dune degradations, branches deposition or plantations (Fig. 5). Ammophila arenaria and Carex arenaria plantations permit a good cover, but marram grass limits the specific richness. Branches use, particularly gorse branches were more efficient as it led to a good cover as well as a good floristic diversity.

Comparison of the efficiency of different techniques of blow-out restoration after two years of experimentation.

4 Discussion

Sand burial is considered as the main factor of the species distribution in a dune system [16]. Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria [17,18] and Galium arenarium are known to be plants well adapted to sand burial and characterize the semi-fixed dune association [12]. The experimental study has shown that this ability come from a good resilience, more than a real resistance. Disturbances are necessary to conserve the semi-fixed dune which is a transitory dynamic stage. Only the sand burial can keep the species Festuca rubra ssp. arenaria and Galium arenarium dominant. An heavy protection of the mobile dune will encourage the closure of the milieu and would reduce the diversity at the community level.

In the dune communities, disturbances such as trampling or rabbit scrapping can benefit to the vegetation in certain conditions of intensity or season. Many authors noticed a positive impact of a moderate grazing or trampling in dry grasslands [7,13,19–24]. They described a limitation of the dominant species allowing less competitive species to develop.

Short dune grasslands morphology is usually attributed to rabbit pressure [25,26]. Boorman and Van der Maarel [27] stressed on the interest of rabbit burrows as an ecological niche for annual species regeneration. It is the case here, notably for the high conservative value species, Omphalodes littoralis which takes advantage of vegetation opening [28].

Trampling can have a positive effect on the vegetation [19]. One year after trampling, the vegetation cover, particularly of the semi-fixed dune, can take advantage of the disturbance. Trampling effects are complex and may result of a two factors balance [13]. The vegetation and soil conditions of humidity seem to be the major factors of the season effect. Trampling damages the vegetation and induce sand movements. At the opposite, soil compaction provides a better stability and also a better humidity for the vegetation [4,29–31].

The disturbance intensity is of great importance [32] while at the higher intensities, trampling or scrapping lead to important degradations, lost of cover and specific richness which are difficult to restore.

The degree of a degradation must be taken into account for the management. Fixed dunes are dynamic systems which response to a degradation can be fast. For example, an opening of the vegetation can completely heal in three or four years since it is protected. But when the vegetation disappear, the soil is eroded and doesn't keep nor organic matter neither seed bank. Healing implies then the beginning of a new succession.

Plantations or branches deposition can be used to accelerate restoration. Marram grass isn't a good tool as it limit the diversity inhibiting the succession and preventing the other species development. Its plantation do not lead to a restoration sensu stricto [33] but to a rehabilitation meaning a stable alternative for the ecosystem. Harvested shoots are known to be a good tool for heathlands restoration [34]. In the fixed dunes gorse branches are particularly efficient as it both permits the best specific richness and the best cover perhaps because of a nitrogen provided of this Fabaceae. This technique can be easily and cheaply realised while material can be collected as part of routine neighbour heathlands management.

Muller [35] proposed three parameters to evaluate biodiversity: richness, equitability and originality. These all components make the fixed dune a vegetation of high biodiversity. Those communities result from a multi-factors action (Fig. 6). Fixed dune is a semi-natural habitat since it is linked to human population for a long time. It implies that disturbances, human activities, wind effects as well as rabbit populations are the sources of the dune biodiversity and must included as tools in management plans.

Scheme of the dynamics of fixed dunes.

Conservation imply the management of the public pressure and not its exclusion. A too heavy protection would enhance the closure of the milieu, a lost of the diversity and the disappearance of many annual species such as Omphalodes littoralis or Linaria arenaria. Restoration can be actively practiced, but a more efficient conservative management would consist of a survey avoiding heavy degradation and a temporary protection of degraded areas.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the O.N.F. (Office National des Forêts), plus the C.E.L.R.L. (Conservatoire de l'Espace Littoral and des Rivages Lacustres) and the Fondation d'Entreprise Procter & Gamble France for financial support.