1 Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is a complex disease, characterised by the successive accumulation of multiple molecular alterations in both the cells undergoing neoplastic transformation and the host cells. These anomalies disturb the expression of genes controlling critical cell processes, causing the initiation of tumourogenesis and genetic instability, and leading to an increasingly invasive and resistant phenotype. That complex genetic basis and the combined heterogeneities of tumour and host cells create the potential for each tumour to be molecularly distinct from all others and consequently to display a unique clinical behaviour. Better characterisation of tumours and understanding of oncogenesis are major requirements to improve patients' survival.

Molecular studies of BC samples have so far successfully elucidated some mechanisms of mammary oncogenesis and identified BC susceptibility genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2) and other altered key genes such as CDH1, MYC or ERBB2. Yet, the clinical applications remain very limited for patients. The main reason is that conventional low-throughput analyses, using a gene-by-gene approach (often based upon specific and limited biological insight), cannot comprehend the molecular complexity of tumours and their clinical diversity.

The Genome Projects and various technological developments now make possible the simultaneous analysis of the activity of many genes in biological samples. The most advanced level of profiling is based on the large-scale measurement of mRNA expression. Among the rapidly emerging technologies, DNA arrays have become the method of choice. There are multiple potential applications in biomedical research, particularly in the cancer field. Four years ago, we launched a project of molecular typing of BC with Nylon DNA arrays combined with radioactive detection. Here, we briefly present the technology and its applications in BC research, including our results.

2 DNA array technology

DNA arrays provide quantitative and simultaneous measurements of the mRNA expression levels of thousands of genes in a biological sample (for a review, see [1,2]). This technology relies on the hybridisation of a labelled target derived from sample RNA to large sets of DNA fragments (the probes representing genes) arrayed on a solid support. The target is produced by reverse transcription of RNA and simultaneous labelling; it contains many different fragments of complementary DNA (cDNA) in various amounts in solution, corresponding to the numbers of copies of the original messenger RNA (mRNA) species. During the hybridisation, the amount of labelled cDNA that hybridises with its probe is proportional to its abundance in the original RNA sample. After washes and image acquisition, the signal present on each probe is automatically detected and quantified; it is proportional to the expression level of the concerned gene. Intensities are normalised and converted into expression levels that then are analysed.

Since hybridisation analysis produces an inordinate amount of data representing thousands of expression measurements, the validation, analysis, interpretation, display and storage of this raw information are not trivial steps. The quality of the data depends on well-controlled hybridisation conditions, such as a good quality RNA, the use of negative and positive controls, an adequate signal-to-noise ratio, and the widest possible dynamic range [2]. The analysis and interpretation of all of the validated data require the use of sophisticated analysis programs to extract the maximum meaningful information. In the past years, methods supervised such as neural networks and unsupervised such as the various clustering techniques have been applied [3].

Two different sorts of DNA arrays have been developed [2]. The first type uses arrays of cDNA clones robotically spotted on a support in the form of bacterial colonies or PCR products. The oldest versions are known as ‘macroarrays’, high-density filters that are made on large Nylon membranes (typically 100 cm2) with the target generally labelled radioactively. Macroarrays are flexible and compatible with the equipment present in most academic laboratories and can effectively assay sets of hundreds or a few thousands genes. We developed this approach in our laboratory few years ago [2,4,5]. ‘Microarrays’ are the miniaturised version: they can contain tens of thousands of PCR products on surfaces of a few square centimetres. The solid support is generally glass and targets are labelled with fluorescence, allowing simultaneous dual hybridisation of the test sample and of a reference RNA sample [6]. Microarrays can also be made on Nylon membranes: in this case targets are labelled with radioactivity [7] or colorimetry [8]. Hybridisation images of microarrays are obtained using high-resolution scanners or a sophisticated flat bed scanner.

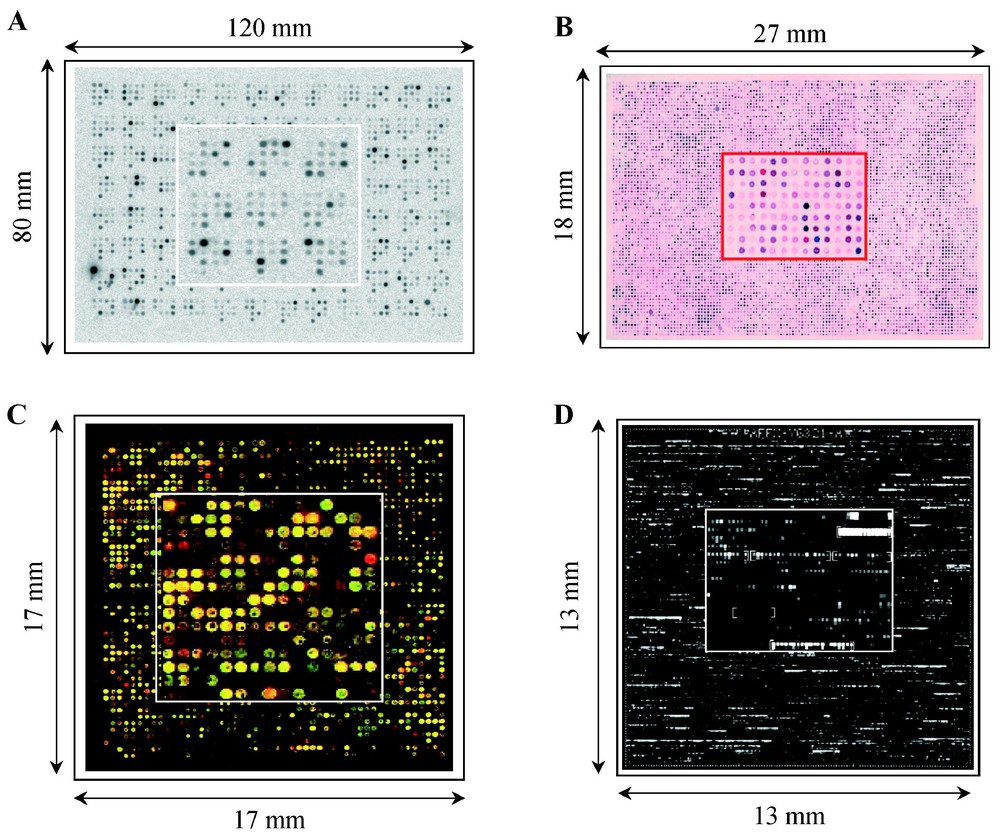

The second type of DNA array was initially developed by Affymetrix (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and is known as an ‘oligonucleotide chip’. Hundreds of thousands of oligonucleotides are directly synthesised in situ on glass slides (a few square centimetres) [9]. For mRNA expression measurements, each gene is represented by a set of oligonucleotides (20–25 bp-long) complemented by a series of mismatched control oligonucleotides used to evaluate background. More recent implementations use longer and more specific oligonucleotides (60–80 bp-long) allowing each gene to be represented by a single sequence [10]. The target is labelled with fluorescence and the detection scanner is similar to that used for glass microarrays. Fig. 1 shows hybridisation images provided by these platforms.

Gene expression measurements with DNA arrays: different approaches. Hybridisation images are shown with an enlargement at the centre of each array. DNA arrays contain robotically spotted cDNA clones (A, B, C) or oligonucleotide directly synthesised in situ (D). (A) Nylon macroarray (hundreds of probes per square centimetre) hybridised with a radioactivity-labelled target and image acquisition with a phosphor screen system. (B) Nylon microarray (thousands of probes per square centimetre) simultaneously hybridised with two colorimetry-labelled targets and image acquisition with a ‘flat-bed’ scanner. The dual hybridisation allows the direct visualisation of differential gene expression between the two samples: the cDNA spot appears red when overexpressed in the target labelled in red, blue when overexpressed in the target labelled in blue and purple when similarly expressed in the two targets (adapted from [8]). (C) Glass microarray (thousands of probes per square centimetre) hybridised with two targets labelled with different fluorescent dyes and image acquisition with confocal laser scanner. The genes differentially expressed between the two samples can be directly visualised on this pseudo-colour image due to dual labelling: the cDNA spot appears red when overexpressed in the target labelled with red dye, green when overexpressed in the target labelled with green dye and yellow when similarly expressed in the two targets. (D) Oligonucleotide chips on glass slide (thousands of probes per square centimetre) hybridised with a target labelled with fluorescent dye and image acquisition with confocal laser scanner. Each gene is represented by a set of oligonucleotides (20–25 bp-long) complemented by a series of control-mismatched sequences (adapted from [9]).

3 Applications in breast cancer research

By providing a global view of mRNA expression, DNA arrays provide a molecular biology tool capable of taking on the complexity and combinatorial nature of BC genetics. Their use is directed towards two major objectives [11]. The first, fundamental, objective is to better understand mammary oncogenesis; the identification of genes that drive disease progression will allow the development of new more specific therapeutics. The second, clinical, objective is to try to define a more accurate BC classification system. The clinical heterogeneity of disease is partially addressed by the current histoclinical parameters; in a number of cases, the treatment response and the clinical outcome vary widely between apparently similar tumours. The use of the comprehensive gene expression profiles of tumours may identify – based on the similarity in their expression profiles – new distinct molecular subgroups of tumours within histoclinically similar groups. Some recent publications suggest that these objectives may be reached within a few years.

3.1 DNA arrays and mammary oncogenesis

DNA arrays are useful to better characterise genes involved in oncogenesis. For the majority of them, the precise function, upstream regulation and downstream effects and their influence on the malignant phenotype remain unknown or unclear. Technology allows the analysis of the transcriptional consequences of activation or inactivation of genes. Examples include those reported following the activation of the MYC oncogene [12] and the inactivation of the p53 tumour suppressor gene [13]. These types of experiments may allow the identification of gene networks involved in cancer. The identification of clusters of co-expressed genes allows the association of these genes with potential new functions [14] and the discovery of common DNA regulatory motifs in their sequences [15].

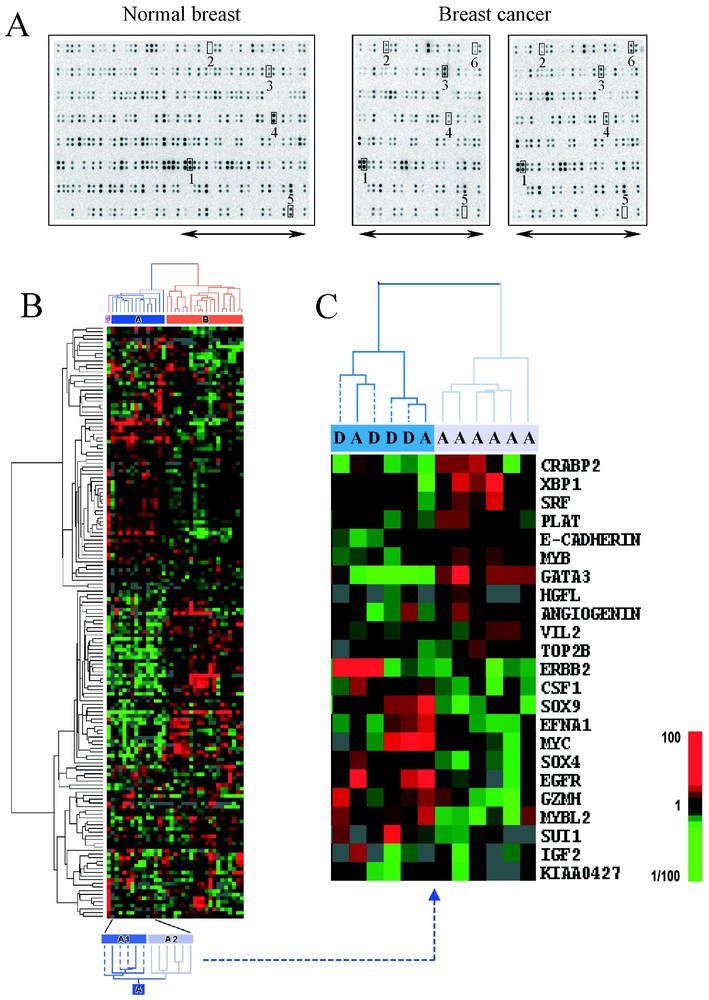

Key genes implicated in BC can be revealed by DNA array experiments comparing the molecular profiles of different stages of the diseases' development. Using Nylon arrays representing ∼200 candidate genes (Fig. 2A), we identified several genes differentially expressed between normal breast tissue and 34 primary breast tumours [16]. The genes ERBB2 and MUC1 were known to be involved in disease, whereas others, such as GATA3, had not yet been insinuated. We compared the expression profiles of node-negative tumours to tumours with massive axillary extension (10 or more positive nodes) and found a positive correlation between the expression level of ERBB2 and the number of tumour-involved nodes. Similar studies comparing primary tumours and metastases have been reported [17].

Large-scale gene expression measurement using DNA arrays in breast cancer. Nylon macroarrays containing PCR products of ∼200 genes spotted in duplicate were hybridised with complex targets made from 5 μg of total RNA (1 normal breast NB tissue and 34 breast cancer BC samples) and 33P-labelled. Data were analysed with hierarchical clustering software [33]. (A) Hybridisation images. The left image corresponds to the whole membrane hybridised with NB target and the right images represent the right part of the membranes hybridised with two BC targets. Some genes are numbered: 1, GAPDH, 2 and 3, STMY3 and ERBB2 overexpressed in NB, 4 and 5, FOS and desmin underexpressed in BC and 6, GATA3 overexpressed in a ER-positive tumour. (B) Coloured representation of expression levels of ∼200 genes in 35 breast samples. Each row represents a gene and each column represents a sample. Expression levels relative to the median across all samples are displayed using a colour scale ranging from green for underexpressed genes to red for overexpressed genes. Hierarchical clustering applied to genes and to samples ordered them according to the similarity of their expression patterns. The respective gene and sample dendrograms represent the relatedness between genes and between samples. Two groups of tumours (A in blue and B in orange) were separated. Group A was further subdivided in two subgroups A1 and A2, with different outcome after chemotherapy. (C) Sub-classification of group A with gene expression profiles. Display of results of hierarchical clustering applied to 12 samples of group A and the top 23 differentially expressed genes between A1 (dark blue cluster) and A2 (light blue cluster) subgroups. Patients of these two subgroups have different metastasis-free and overall survivals (dotted branches, patients who relapsed and died). (Adapted from [16].)

Another application is in the development of new anticancer treatments. In addition to the identification of new therapeutic targets, DNA arrays may also be used to investigate the resistance of tumours to treatments. Knowledge of the relationships between the hormone sensitivity of BC and the presence of oestrogen receptor (ER) is not sufficient to understand the variable response of tumours to hormonal treatments. It is probable that other genes related to ER status are more useful in predicting treatment responsiveness. Their identification might influence therapeutic decisions and stimulate the development of new anticancer drugs. To search for genes whose expression is affiliated with the ER status, expression profiles of BC cell lines were first compared [5,18]. A strong correlation between the expression of ER and GATA3 transcription factors was evidenced and was further confirmed with tissue samples [16,19–21]. By comparing the expression profiles of ∼200 candidate genes in ER-positive versus ER-negative tumours, we identified several genes which mRNA level was associated with ER status, including GATA3, XBP1, MYB [16]. Several molecular mechanisms of chemoresistance have been identified, including increased drug efflux outside the cell, but many more mechanisms probably operate to determine responsiveness to chemotherapy. DNA arrays by monitoring large-scale changes in gene expression related to the acquisition of the chemoresistant phenotype in cancer cell lines [22] can help to identify new predictive factors.

3.2 DNA arrays and prognostic classification of breast cancer

Because of the great heterogeneity of disease, treatments need to be tailored to each tumour phenotype. This major challenge depends on the improvement of tumour classification.

The first demonstration of the utility of DNA arrays for cancer classification came from the profiling of cell lines [23] showing that lines derived from the same organ clustered together according to their gene expression patterns. This was further confirmed by Golub et al., who used expression profiles of bone marrow collections to distinguish acute myeloid leukaemia from acute lymphoid leukaemia [24]. Alizadeh et al. [25] then showed the prognostic value of such molecular classification. The authors identified two new sub-types of large B-cell diffuse lymphomas with biological and clinical relevance: the tumours with a pattern close to that of germinal centre B cells had a significantly better prognosis than the tumours with expression patterns corresponding to activated B cells.

Analyses of BC samples have revealed extensive heterogeneity of tumours at the transcriptional level and the ability of separating them, using clustering techniques, on the basis of differing ER status [16,19,20,26–29]. We also identified differences in survival between new molecularly distinct tumour subgroups [16,27]. Profiling of 34 localised breast tumours with Nylon macroarrays containing ∼200 candidate genes and hierarchical clustering analysis allowed to distinguish, among tumours with poor prognosis according to classical criteria, two subgroups with different survival after adjuvant chemotherapy [16]. This separation, which resulted from expression profiles of 23 discriminator genes, was not possible using the conventional prognostic features. Among these genes, some were already associated with the prognosis of disease (ERBB2, EGFR, MYC) as well as other genes not yet recognised as important (GATA3, CRABP2 and EFNA1). We validated and extended these results by measuring the mRNA expression of a thousand candidate genes (including the previous 200 genes) in a larger and independent series of 55 poor prognosis primary BC treated with adjuvant chemotherapy [27]. Using a refined 40-gene set derived from the previous one, we distinguished among the 55 tumours three classes with significantly different 5-year survival.

4 Discussion and perspectives

Such prognostic classifications were recently reported in localised BC [20,29], in locally advanced BC [26] and in multiple forms of disease [28]. In all these studies, including ours, no prognostic classification as accurate as expression profiles-based classification could be obtained using classical prognostic factors. In every case, the classification required expression measurements of some tens of genes that probably included potential molecular targets for new and more specific therapies. To further explore the validity of results we compared the lists of discriminator genes identified. Despite several different methodological aspects, 26 genes were found in at least two lists [30]. Reassuringly, some have a known prognostic value (e.g., ESR1, ERBB2) but most are not yet associated with prognosis but have functions that make them prime candidates for novel therapeutic targets.

All these studies thus revealed the great and promising potential of DNA arrays for capturing the true diversity of BC and refining the prognostic classification. But a number of issues need to be addressed before DNA arrays translate into clinical benefits [30]. We discuss here only the issue concerning the amount of starting RNA required that depends on the sensitivity of the chosen technique.

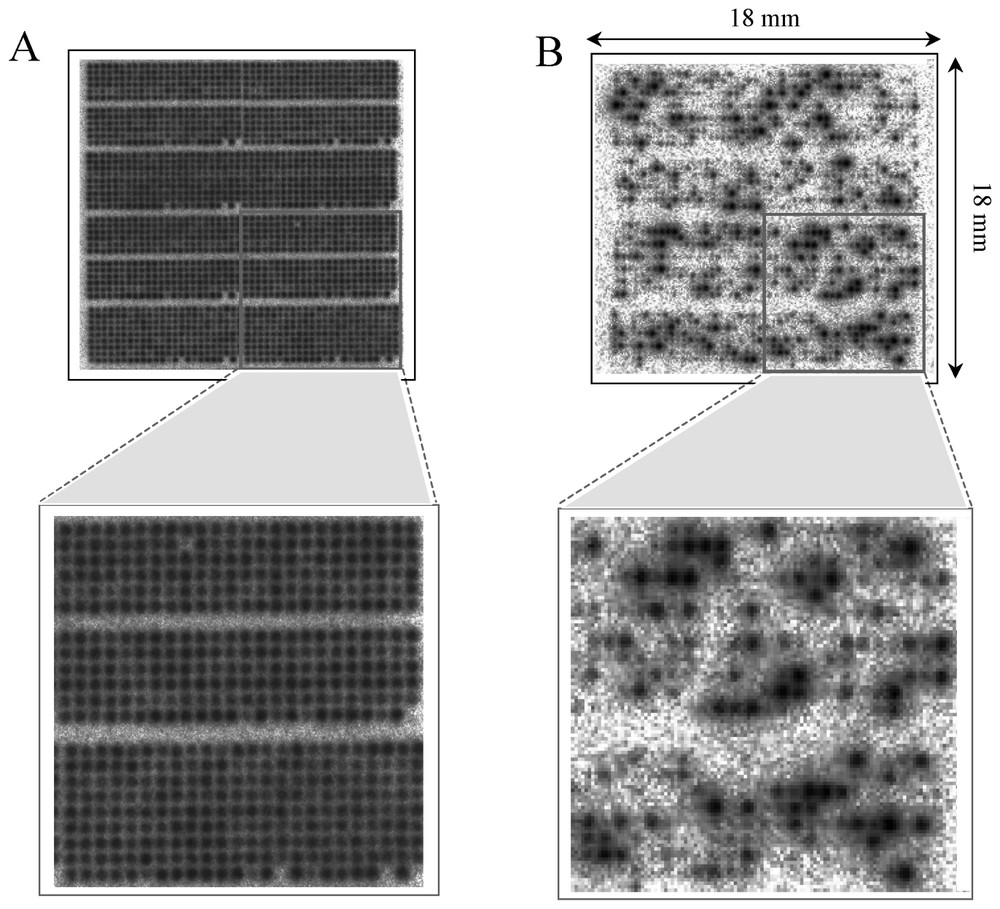

For less sensitive techniques, a greater quantity of starting material is required. One way to obtain a usable amount is to amplify the mRNA before labelling using linear amplification methods [31], but that remains coupled with a risk of modifying the relative abundances of individual sequence species in the target. However techniques are being improved, even though there is some bias in the amplification [32]. Another solution is to improve the intrinsic performances of current DNA arrays. Glass microarrays and oligonucleotide chips require a few micrograms of mRNA, while Nylon macroarray uses some micrograms of total RNA (5 μg in our studies). We compared the sensitivity of these three implementations without taking into account mRNA amplification methods [7]. Relating the minimal relative abundance, generally reported by authors as a sensitivity limit, to the target concentration, and ultimately to the size of the starting material, we showed that the sensitivity for Nylon macroarrays was in fact similar to other approaches: 20 to 30 million mRNA molecules are necessary in the sample to be detectable. We suggested that this sensitivity was mostly due to the high capacity of Nylon membranes (allowing large amounts of probe and correspondingly large signals) added to the excellent intrinsic sensitivity of radioactive detection. We then showed that Nylon microarrays combined with radioactive labelling provide sensitive expression measurements using submicrogram amounts of total RNA, i.e. 100 times less than the other methods. Fig. 3 shows images of Nylon microarray with 2000 cDNA clones hybridised with radioactive 33P-labelled targets. It was first hybridised with a vector target corresponding to a sequence common to all spotted PCR products (Fig. 3A): this allows the estimation of the amount of target DNA accessible to hybridisation. It was then stripped and hybridised with a complex target made from only 0.5 μg of total RNA extracted from a cancer cell line (Fig. 3B). These developments are important for the application of DNA arrays in clinical oncology, because they will allow profiling of small tumour samples including biopsies, minimal residual disease or homogeneous material provided by microdissection.

Nylon microarrays with radioactive detection. Nylon microarray (1.8×1.8 cm2) containing 2000 cDNA clones hybridised with radioactive 33P-labelled targets. Hybridisation with a vector oligonucleotide (A) and with a labelled target made from 0.5 μg of total RNA (B). Enlargements of a part are shown under microarrays.

5 Conclusion

DNA arrays provide a revolutionary tool to discover and analyse the complex molecular basis of cancer. Since their first appearance in the mid 1990s, many developments have allowed them to be accessed by more and more researchers. Many studies have confirmed their great potential interest in the scientific, biomedical and pharmaceutical fields of oncology. The clinical benefit for patients remains to be demonstrated. Combined with other emerging large-scale molecular analysis methods, they will provide great insights into our understanding of cancer. This would boost the development of new specific anticancer therapeutics and improve the current tumour taxonomy allowing the prediction with accuracy of the outcome of the disease, its sensitivity to a given treatment, and the delivery of treatments targeted to each individual tumour.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Inserm, CNRS, Institut Paoli-Calmettes, and the ‘Association pour la recherche sur le cancer’, the ‘Fédération nationale des centres de lutte contre le cancer’, and the ‘Ligue nationale contre le cancer’.