1 Introduction

Lignin is present in plant cell walls as a three-dimensional (3D) macromolecule associated with cellulose and hemicelluloses via both covalent bonds and non-covalent interactions [1]. Determining the 3D structure of macromolecular lignin is essential for a proper understanding of physical, chemical and biological properties of lignin in the cell walls. For this purpose, the following information with respect to lignin macromolecule in different morphological regions of the cell wall is necessary: (i) distribution and frequencies of different kind of monomer units, (ii) distribution and frequencies of inter-unit bonds; (iii) type and distribution of bonds between lignin and polysaccharides; (iv) higher-order structure and size of lignin macromolecule; (v) 3D assembly of lignin, hemicelluloses and cellulose. Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba Linn.) is a particularly suitable tree species for investigation of structure of softwood lignin. The anatomical features of the vascular tissue and xylem tissue of ginkgo are similar to those of conifers [2]. A major part of ginkgo lignin is composed of guaiacylpropanoid units [3], and the structure of ginkgo lignin is very close to that of conifer lignin. In applying an isotope tracer technique for structural analysis of lignin, selective labeling of hydrogen or carbon with radio- or stable isotopes in guaiacyl lignin can be conveniently achieved by feeding specifically labeled coniferin to the growing stem of ginkgo wood [4,5]. Non-destructive analysis of the labeled isotopes by microautoradiography or by differential 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy can afford the necessary information (i), (ii), (iii) and a part of (v) [3–5]. Direct observation of the lignin deposition process through a powerful electron microscope will be a promising approach to obtain information (iv) and (v) with respect to the different morphological regions of the cell wall.

This paper deals with observations of lignifying ginkgo cell walls by a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM).

2 Materials and methods

Small blocks containing differentiating xylem were cut out from a growing stem of a ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba Linn.), and fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.1). Radial and cross sections of 60–100-μm thickness were prepared using a freezing/sliding microtome. Sections were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h at room temperature. The sections were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series and isoamyl acetate, and dried using a critical point dryer (HCP-2, Hitachi) using liquid carbon dioxide. Some sections were subjected to delignification according to the procedure applied for pinewood by Hafrén et al. [6] with slight modification. Wood sections were heated in acetate buffer (pH 3.5, 4 ml) containing sodium chlorite (40 mg) and acetic acid (12 mg) at 75 °C with addition of the same amount of sodium chlorite and acetic acid seven times over 2 h. Removal of the hemicelluloses was carried out by extraction of the delignified section with 24% potassium hydroxide overnight followed by extraction with 18% sodium hydroxide containing 4% boric acid at room temperature [7]. These sections were washed with water, acetate buffer (pH 3.5), and phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), then stained with 0.1% ruthenium tetroxide in phosphate buffer in the dark under cooling with ice water for 10 min. After washing with buffer and water followed by drying with graded ethanol series, the sections were subjected to freeze-drying using t-butanol. The sections were coated with approximately 1-nm-thick platinum/carbon by rotary shadowing at an angle of 60°. Some sections were coated with approximately 1-nm-thick platinum and palladium using ion sputter (Hitachi E-1030). The sections were examined using a FESEM (S-4500, Hitachi) at an accelerating voltage of 1.5 kV and 3–5 mm of working distance.

3 Results and discussion

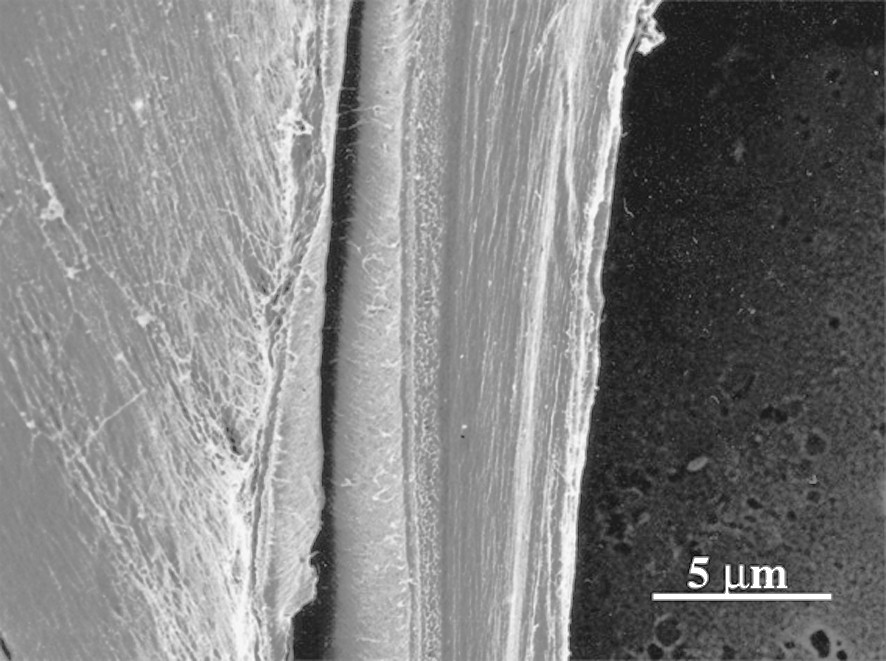

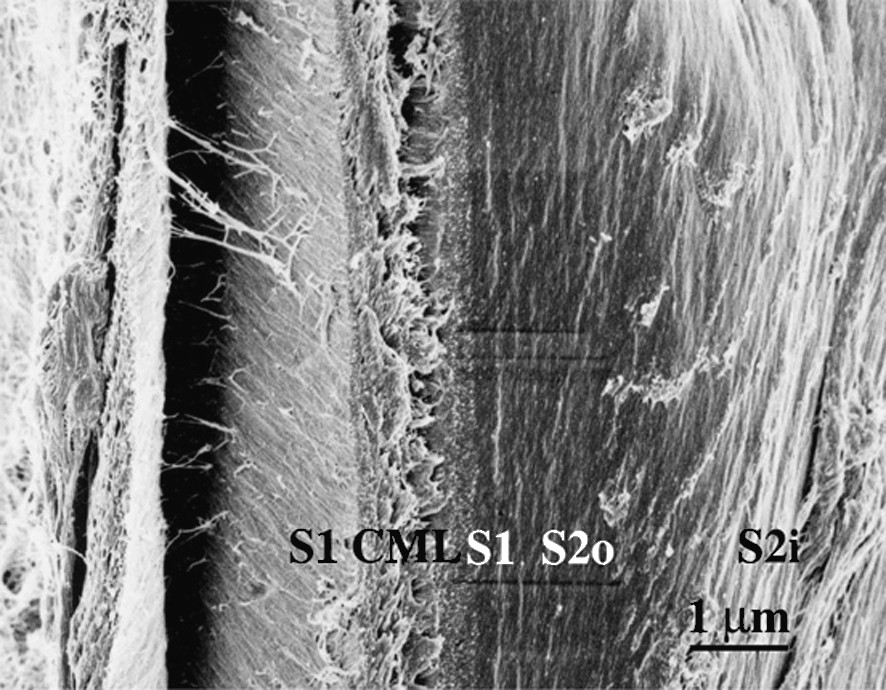

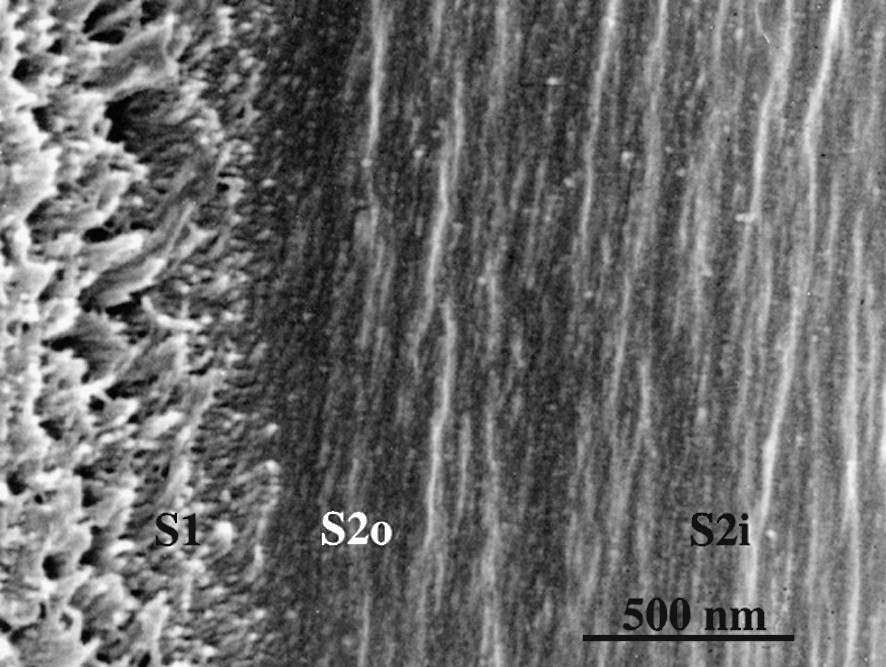

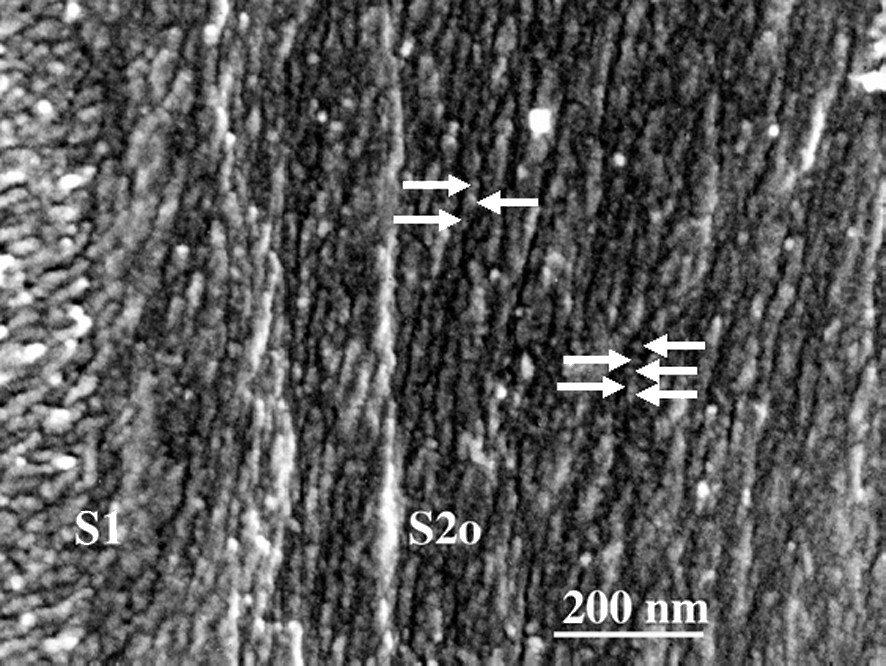

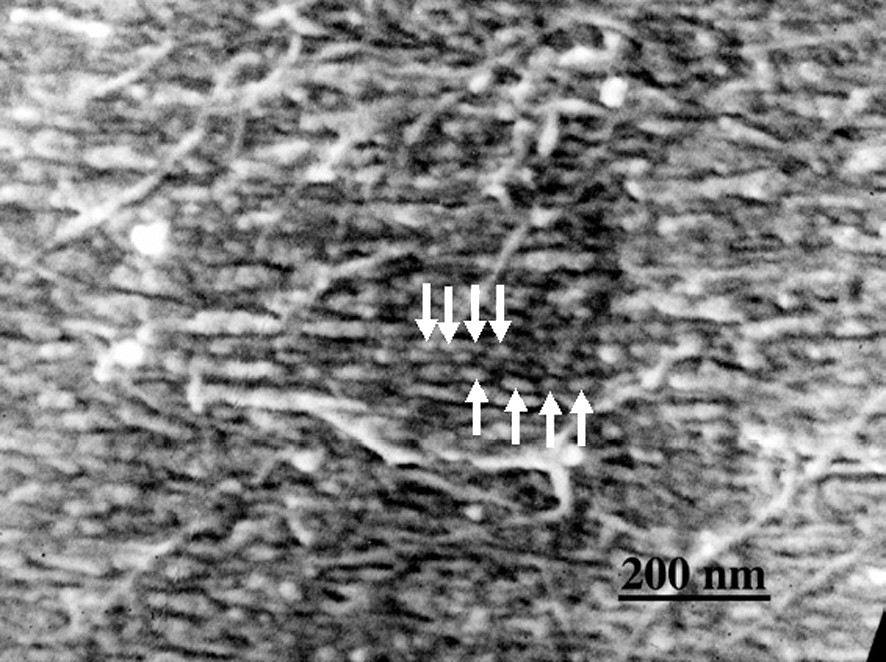

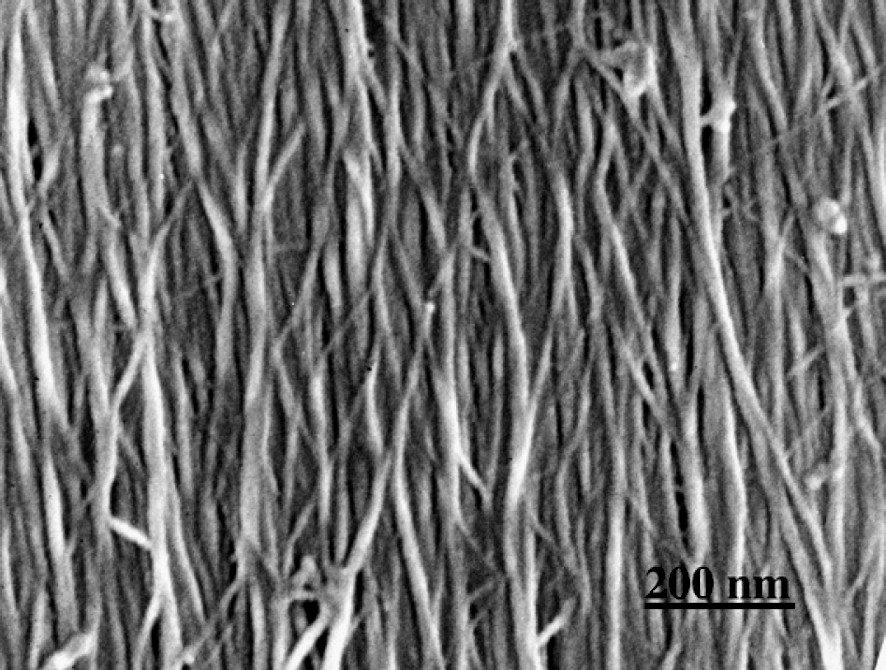

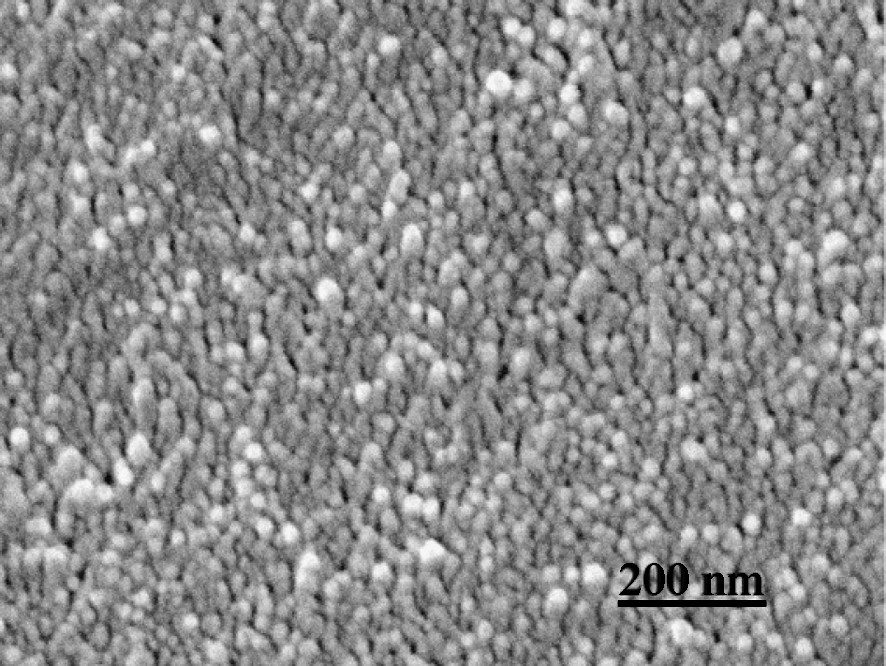

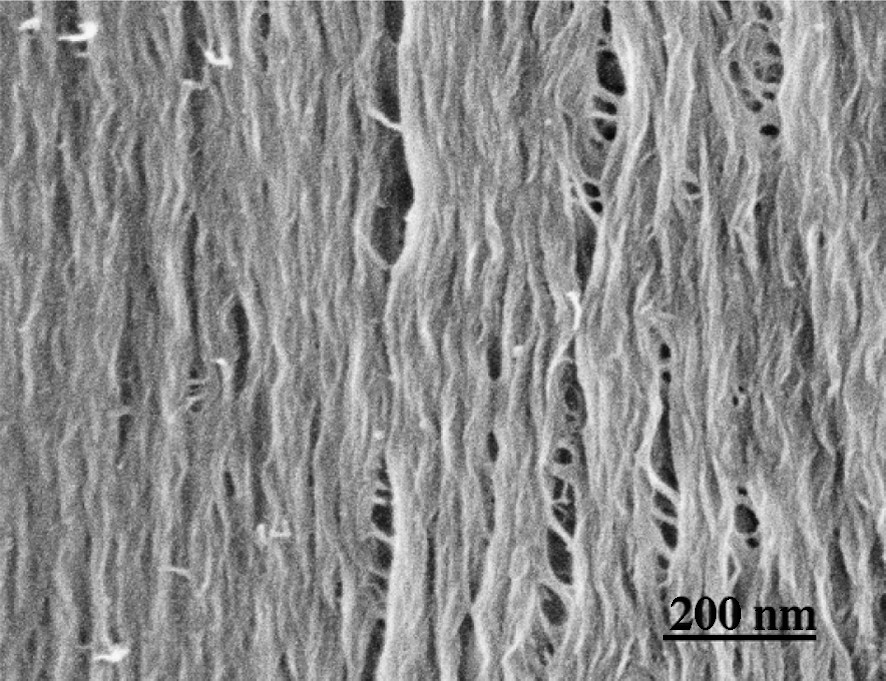

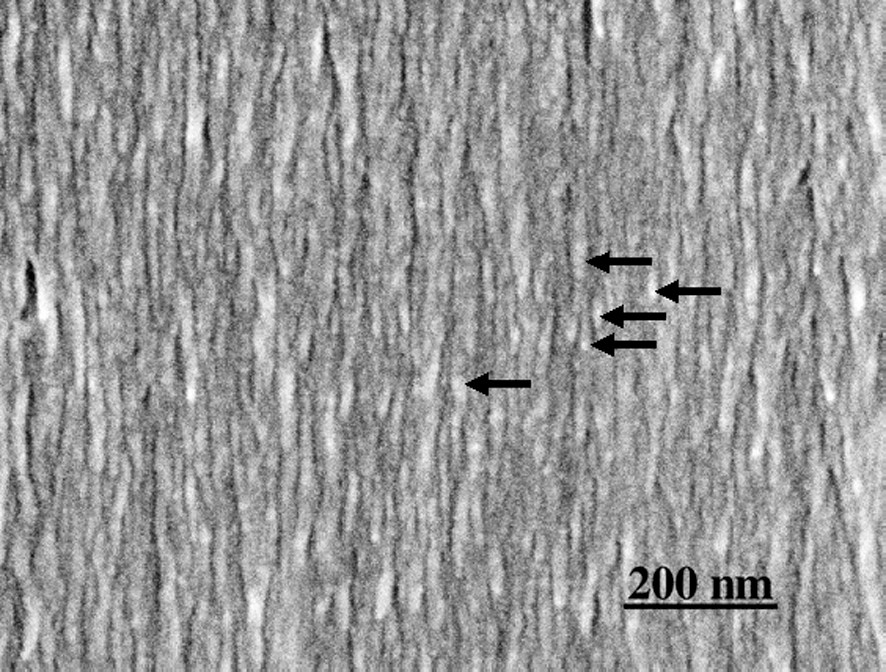

Fig. 1 shows the sectional view of a cell wall in the formation stage of the middle layer of the secondary wall (S2). A higher magnification view (Fig. 2) shows that in the outer part of S2 (S2o), lignin deposited on the CMFs, while in the inner part of S2 (S2i) lignin deposition is not completed yet and CMFs are clearly visible. In the micrograph taken at higher magnification (Fig. 3), deposited lignin covers cellulose microfibrils (CMF), making the image of CMFs obscure. Fig. 4 shows the higher magnification view of S2o. Macromolecular lignins of almost the same size are observed as bead-like modules on a CMF. For determination of the size of the module, careful consideration should be given on the shrinkage of the module during preparation of a dry wood section for observation by FESEM. The thickness of the coating (about 1 nm) should be also taken into consideration. However, because the shrinkage will be negligible in the direction along the crystalline CMF, the observed average distance

A view of developing cell wall cut parallel to CMFs in middle layer of secondary wall (S2) at a stage of lignin formation.

Higher magnification view of Fig. 1. Compound middle lamella (CML), outer layer of secondary wall (S1) and outer part of S2 (S2o) are lignified, while inner part of S2 (S2i) is not yet lignified.

Higher magnification view of Fig. 2. CMFs are covered with deposited lignin.

Higher magnification view of Fig. 3. Lignin modules (arrows) are growing along CMFs at an almost regular distance.

S1 layer at a stage of formation of lignin modules (arrows).

Innermost surface of a tracheid at a S2 formation stage.

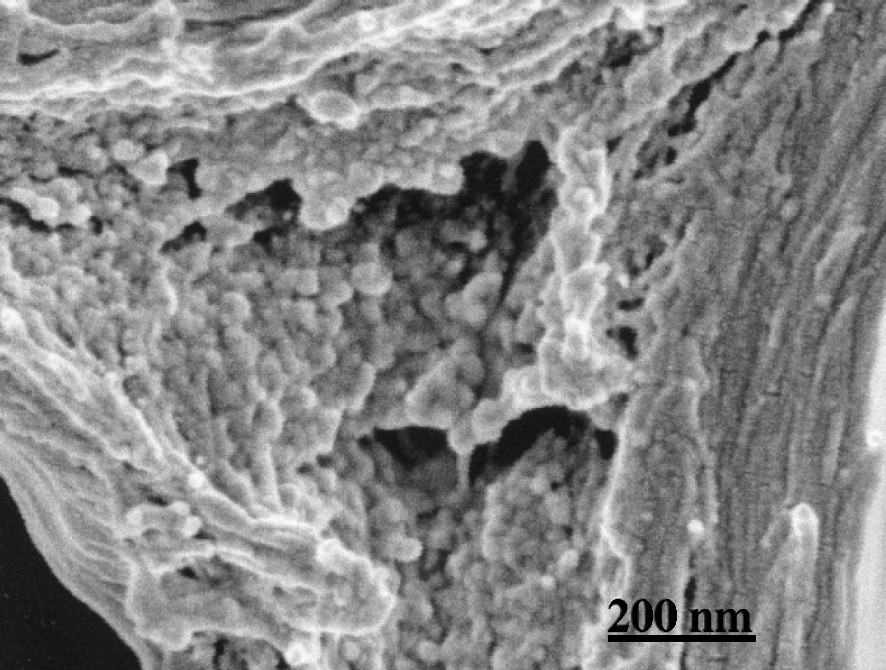

Cell corner region. Large globular modules form aggregates at random.

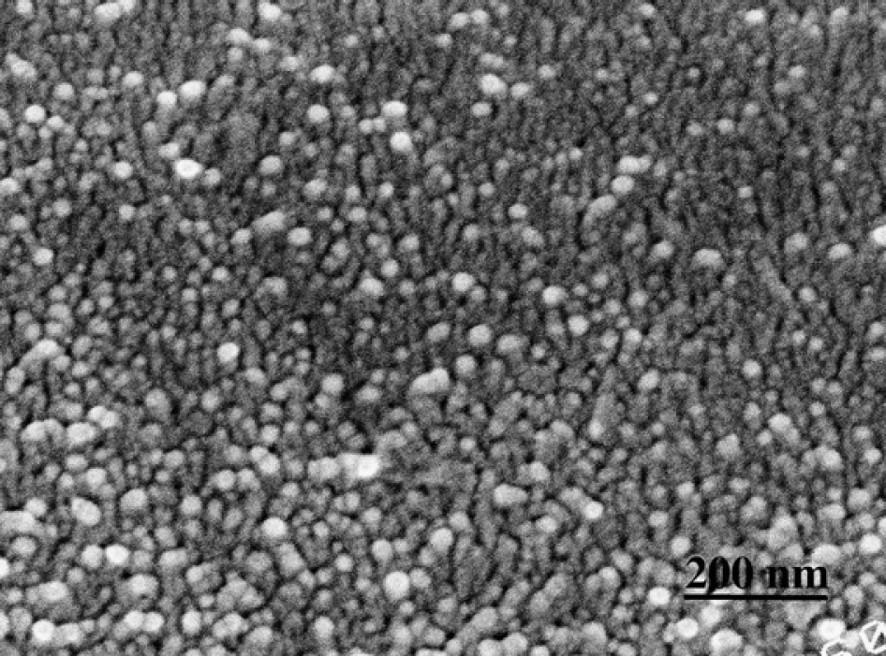

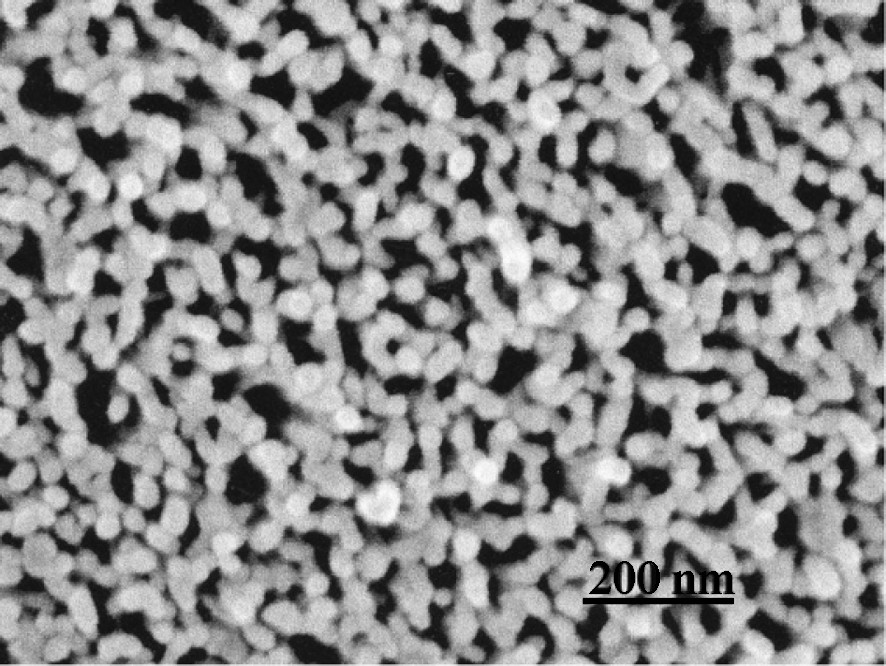

S2 layer cut perpendicular to CMFs. Lignifying wood section.

S2 layer cut perpendicular to CMFs. Delignified wood section.

S2 layer cut parallel to CMFs. A wood section from which lignin and hemicelluloses are removed.

S2 layer cut perpendicular to CMFs. A wood section from which lignin and hemicelluloses are removed.

Though the detailed mechanism of polylignol formation in wood cell walls is not yet fully elucidated, Ralph et al. showed that ferulate polysaccharide esters or diferulate polysaccharide esters appear to be acting as initiation or nucleation sites for lignification in grasses [12,13]. Carnachan and Harris reported that ferulic acid is bound to the primary cell walls of all gymnosperms including ginkgo [14]. If this kind of ferulate-carrying hemicellulose would associate at regular intervals along the CMF, lignin modules could be formed at regular intervals. Fig. 12 shows thin bead-like hemicelluloses strung with the CMFs in ginkgo S2 that remained after lignin is removed. The interval of the remaining hemicellulose is around

S2 layer cut parallel to CMFs. Delignified wood section. Thin modules composed mainly of hemicelluloses (arrows) remain along the CMFs.

The lignin modules start growing at a regulated distance surrounding the CMFs in the differentiating secondary walls, and the tubular bead-like modules physically and chemically bound to hemicelluloses grow finally to fill up the space between the CMFs. Well-defined modular structures are not observed in completely lignified cell walls. Because the growing end of the module will be mainly 4-O-β bonded guaiacylglycerol units, frequent formation of dibenzodioxocin structures [16] may occur at the boundaries of fusing modules as the final step of lignification. However, the frequency of the bonds formed at the fusion boundary may not be so high compared with the bond frequency inside of the module. A modular structure of lignin has been proposed based on molecular weight distribution of chemically degraded lignin [17].

The size of one tubular-bead of lignin-hemicellulose module in the S2 of dry ginkgo tracheids is tentatively estimated to be

4 Conclusion and future prospects

Observation of lignifying secondary cell walls of ginkgo tracheids by FESEM showed that lignin–hemicellulose complexes are formed as tubular bead-like modules surrounding the CMFs with regular spacing. The modules grew finally to fill up the spaces between CMFs. The size of one tubular module in S2 was tentatively estimated to be about

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Prof. M. Fujita and Dr T. Higasa (Kyoto University), and Prof. T. Okuyama, Prof. K. Fukushima, Mr Y. Hosoo (Nagoya University) for providing useful information and conveniences for experiments by FESEM. Thanks are due to Prof. J. Ralph (US Dairy Forage Research Center) for reading the manuscript and helpful discussions.