1 Introduction

Ligand-gated ion channels (LGICs) of the Cys-loop super-family mediate fast neurotransmission. These receptors are composed of three domains: an extracellular domain composing the ligand-binding pocket, a transmembrane ion channel domain, and an intracellular domain that carries phosphorylation sites [1,2]. Upon agonist application, these receptors undergo a rapid conformational transition from a resting basal state (B state) to an open-channel state (A state). Prolonged application of the agonist promotes the stabilization of the receptor in a refractory high-affinity desensitized state (D state). This kinetic scheme is accounted for by an extended concerted allosteric model [3]. Early studies with chimeras between members of the LGICs super-family revealed that functional chimeric constructs can be obtained between α7 nicotinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptor (nAChR) and serotonin type-3A (5HT3A) receptor, underlying the functional autonomy of the ligand-binding and channel domains [4].

In the absence of X-ray data for the whole receptor, structures of individual domains are now available to mean atomic resolution [5,6]. First, the structure of an acetylcholine-binding protein (AChBP) from the fresh water snail Lymnaea stagnalis, homologous to the extracellular domain of nicotinic receptors [7], has been reported at 2.7 Å by X-ray crystallography [5]. The structure revealed a β-sandwich core composed of two twisted β-sheets. This pentameric protein, which naturally lacks an ion channel, offers an exceptional template for the modelling of the ligand-binding domain for the nicotinic receptor and all members of the LGIC [8–10] and led to the resolution at the atomic level of the complex of nicotine with its specific binding site [11]. Second, electron-microscopy (EM) pictures of Torpedo marmorata receptor have resolved at 4 Å an all α-helix folds of the transmembrane domain [6]. Though the recent EM pictures still lack atomic resolution, the data offer the possibility to build a 3D model of the entire receptor: a synaptic β-sandwich ligand-binding module coupled to a four transmembrane α-helices ion channel (Taly et al., manuscript submitted).

Cross-linking studies with the GABA-A receptor pinpointed a set of loops that interact between the two domains [12]. Asp-149 residue of the highly conserved Cys-loop (or loop 7 in nomenclature from [5]) is at about 5 Å from Lys-279 located in C-terminal end of helix M2 in the α1-subunit in GABA-A receptor [12]. The homologous residue in β2-subunit Asp-146 was found to interact with Lys-215 in the pre-M1 segment [13]. Similarly, Asp-57 of loop 2 is also close to Lys-279 in the M2 helix in the β-subunit in GABA. These studies define at least loops 2 and 7 located at the bottom side of the extracellular domain that link the synaptic and ion channel domains. However, how the two domains interact in the course of allosteric transitions remains unclear.

In this paper, we fused AChBP either with the ion channel and intracellular domains of the cationic serotonin type-3A (5HT3A) receptor or with the anionic glycine receptor. First, AChBP was chosen because its atomic structure is known [5]; second AChBP forms an homopentameric assembly as do 5HT3A and glycine receptors; and finally AChBP has most likely evolved without the constraint of an ion channel, and may (or not) have lost the possibility to undergo allosteric transitions. Here, we show that AChBP linearly fused with an ion channel forms high-affinity sites similar to that of the water-soluble form of AChBP; however, the fused protein is not targeted to the cell surface. Yet, after substituting a ring of three loops located at the putative membrane side of the three-dimensional structure of AChBP (loop 2, 7 and 9) with the homologous residues of 5HT3A, the resulting chimera AChBP(ring)/5HT3A is successfully targeted to the cell surface, as seen by immunofluorescence and assembles as a pentamer, as observed on sucrose gradient sedimentation. However, this chimera displays a high proportion of low-affinity sites (micromolar range) for the resting state stabilizing competitive antagonist α-bungarotoxin (α-BgTx) and does not give significant ACh-gated currents in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments. Interestingly, in vitro binding assays with membrane fragments prepared from cells expressing AChBP(ring)/5HT3A chimera show a decrease in the apparent affinity for agonist concomitantly with an increase of the proportion of high-affinity sites (low nanomolar range) for α-BgTx. These results demonstrate that when fused into a ring chimera with the 5HT3A channel, AChBP is capable of making allosteric transitions when expressed in HEK-293 cells, but remains stabilized in the high-affinity state for epibatidine, which likely corresponds to a desensitized form in LGICs. We conclude that part of the AChBP structure has retained during evolution some structural elements that allow allosteric transitions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 cDNA constructs and site-directed mutagenesis

Synthetic genes for the Lymnaea stagnalis AChBP and Gallus gallus α7 extracellular domain were engineered by multiple PCR amplifications of synthetic oligonucleotides containing silent restriction sites at 50 base pair intervals respecting mammalian-codon frequency usage. cDNAs encoding AChBP and the α7 extracellular domain were subcloned into the plasmid pMT3 and both contained in

2.2 Cell cultures and transfection

Plasmids were transiently transfected into human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells by calcium phosphate precipitation. For electrophysiology and immunofluorescence, cells were plated on poly-l-lysine (100 μg/ml)-coated glass coverslips prior to transfection. Cells were maintained in minimum essential Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (Invitrogen), 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were washed with fresh medium and were used 24 h after for further experiments.

2.3 Binding experiments

[125I]α-Bungarotoxin and [3H]epibatidine binding assays were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), as described previously [14], except that GF/C filters (Whatman) were soaked in 0.5% polyethylenimine (PEI, Sigma). Membrane fragments were prepared from transfected cells as described [15] in PBS supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). Water-soluble AChBP expressed in the HEK-293 cells culture media was concentrated in a centrifuge filter device (YM-50, Amicon) followed by a dialysis against PBS for 3 h. [125I]α-Bungarotoxin and [3H]epibatidine binding was determined as described above. In all cases, the

2.4 Sucrose gradient

Membrane fragments were solubilized for 3–4 h in 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.4, 0.02% NaN3, and 1% Triton-X 100. Solubilized chimeric receptors were layered onto 5–30% linear sucrose gradient and centrifuged for 14 h at 37 000 rpm (

2.5 Electrophysiology

Electrophysiological recordings were performed as described previously [14]. Briefly macroscopic currents were recorded 2–3 days after transfection, using the whole-cell patch-clamp technique [16], with cells at a holding potential

2.6 Immunofluorescent localization of the chimeras

Transfected HEK-293 cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. To label the C-terminal domain, fixed cells were incubated for 2 h with rabbit polyclonal anti-HA antibody (Sigma) diluted 1:100. Fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (diluted 1:1000, Vector) was then applied for 1 h. Intracellular expression of the chimeras was determined by addition of 0.1% Trition X-100 for membrane permeabilization. Glass coverslips were mounted in vectashield mounting medium with a nucleus dye (Dapi, Vector) and immunofluorescence was observed using a Zeiss–Axiophot microscope.

3 Results and discussion

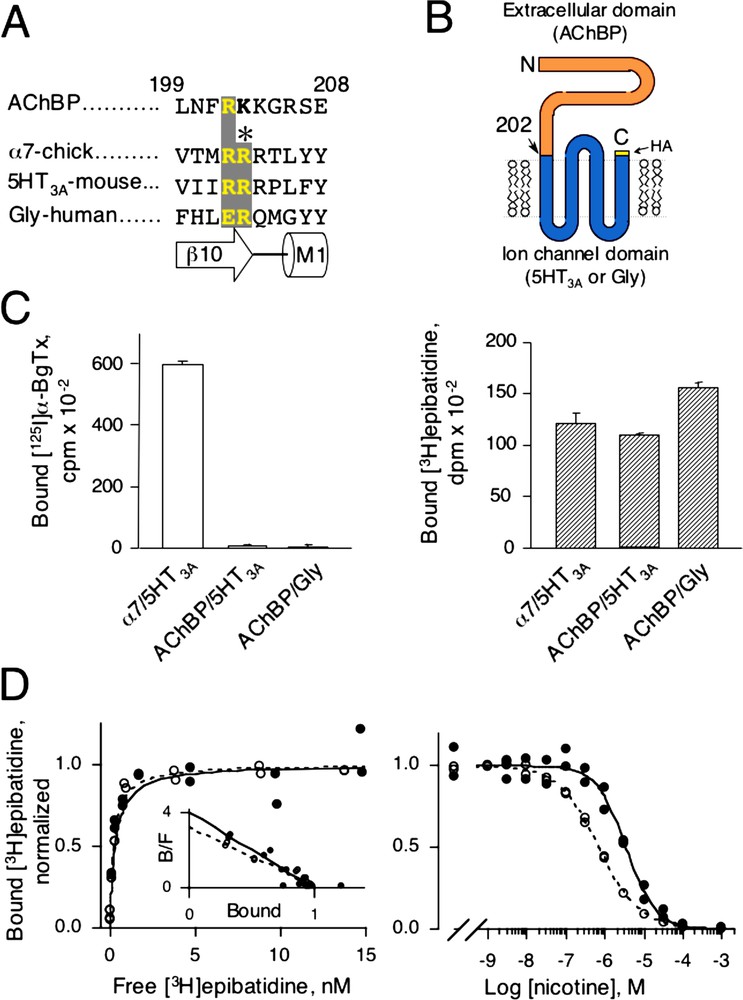

Lymnaea AChBP was fused linearly either with the mouse cationic serotonin type-3A (5HT3A) ion channel or with the human anionic glycine ion channel at the level of pre-M1 (Arg-202) thus yielding AChBP/5HT3A or AChBP/Gly chimeras (Fig. 1A and B). We chose this locus because of the presence of the highly canonical Arg-203 residue that is not conserved in AChBP, but may be crucial for the expression of a full-length receptor (Fig. 1A). Transient transfection of the different cDNAs into HEK-293 cells did not give surface binding sites for either AChBP chimeras as assayed in intact cells with 4.5 nM of the cell-impermeant competitive antagonist [125I]α-bungarotoxin ([125I]α-BgTx) in conditions where significant [125I]α-BgTx binding sites were observed with the α7/5HT3A chimera fused at the same residue Arg-202 (Fig. 1C, left). Similarly, no intracellular [125I]α-BgTx binding sites were detected when cells were made permeable with 0.5% (w/v) of saponin (data not shown). However, both chimeric receptors showed equivalent [3H]epibatidine binding, a cell-permeant agonist (Fig. 1C, right). Saturation experiments with [3H]epibatidine revealed that both AChBP chimeras displayed very high-affinity sites for epibatidine (

(A) Sequence alignment of Lymnaea AChBP, chick α7, mouse 5HT3A, and human Glycine receptors in the pre-M1 region. Numbering refers to the AChBP. Under the sequence alignment is shown the corresponding secondary structures with strand β10 of AChBP and α-helix M1 of the ion channel. (B) Cartoon of the predicted topology of a subunit belonging to the LGIC super-family. Here, AChBP (the extracellular domain) is linearly fused after Arg-202 with either 5HT3A or glycine ion channel. The human hemagglutinin (HA) epitope is fused to the C-terminal end of the chimera. (C) [125I]α-BgTx (left) and [3H]epibatidine (right) binding for the chimeras α7/5HT3A, AChBP/5HT3A and AChBP/Gly. 4.5 nM [125I]α-BgTx for 2 h or 5 nM [3H]epibatidine for 1 h were added on intact cells expressing chimeras. Samples were filtered and counted. Values ± SD are specific binding determined by the difference between total binding (without nicotine) and non-specific binding (with 1 mM l-nicotine). (D) Representative [3H]epibatidine saturation (left) and competition (right) experiments for AChBP/5HT3A chimera (●) and water-soluble AChBP (○). For saturation, non-specific binding was determined with 1 mM l-nicotine and indicated values are specific binding. For competition 2 or 5 nM [3H]epibatidine was used for water-soluble AChBP or AChBP/5HT3A chimera, respectively. For both plots, normalized duplicate values of bound [3H]epibatidine are shown. Inset: Scatchard representation. Masquer

(A) Sequence alignment of Lymnaea AChBP, chick α7, mouse 5HT3A, and human Glycine receptors in the pre-M1 region. Numbering refers to the AChBP. Under the sequence alignment is shown the corresponding secondary structures with strand β10 of ... Lire la suite

Binding parameters of the chimeras

| [3H]epibatidine binding | Nicotine binding | α-BgTx binding | ||||

| Constructs | nH | nH | K (nM) | nH | ||

| Soluble AChBP | 0.20±0.06 | 0.90±0.08 (3) | 58 ± 6 | 0.80±0.03 (2) | 4.6±2.91 | 1.6±0.01 (2) |

| Intact cells | ||||||

| AChBP/5HT3A | 0.52±0.27 | 0.86±0.16 (2) | 370 ± 45 | 1.00±0.16 (2) | ND | |

| AChBP/Gly | 0.25±0.02* | 0.94±0.17* (1) | 145 ± 29* | 0.94±0.16* (1) | ND | |

| AChBP(ring)/5HT3A | 2.13±0.32 | 1.06±0.03 (3) | 3680 ± 750 | 0.73±0.03 (2) | 3500±11302 | 0.46±0.07 (3) |

| 20±49 [23±13]3 | 0.78±0.27 (3) | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Membrane fragments | ||||||

| AChBP(ring)/5HT3A | 14.2±3.9 | 0.94±0.04 (2) | 14 800 ± 1100 | 1.66±0.84 (2) | 173±782 | 0.38±0.06 |

|

|

0.67±0.01 (3) | |||||

|

|

1 α-BgTx binding affinity was measured by competition against initial rate of [125I]α-BgTx as previously described [15].

2 α-BgTx binding was measured by competition against [3H]epibatidine binding, yielding apparent K as described in [14] from fitting a one-site inhibition model.

3

For AChBP(ring)/5HT3A chimera a two-site inhibition model is also given according to equation:

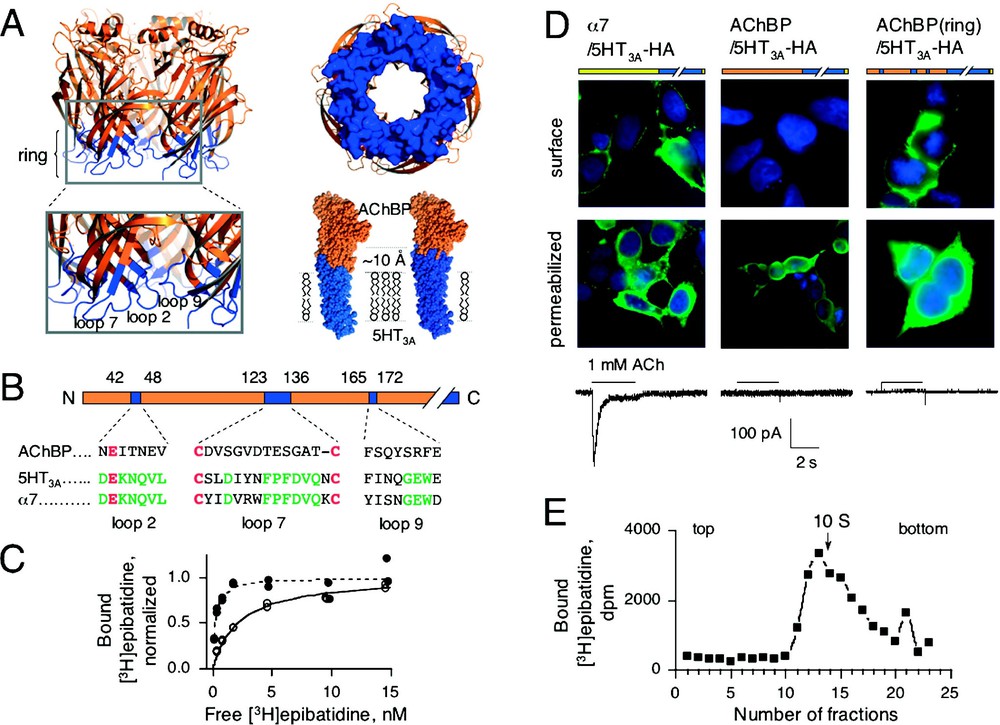

(A) Left, three-dimensional (3D) structure of AChBP (PBD code: 1I9B) [4] with loops 2, 7 and 9 coloured in blue. These loops form a ring of residues located at the membrane side of the 3D structure of AChBP. Right up, view from the channel of the ring. Right down, CPK representation of 3D comparative models of chimeras AChBP/5HT3A and AChBP(ring)5HT3A. AChBP and 5HT3A residues are coloured in orange and blue, respectively. The ring of 5HT3A residues extends 10 Å towards the extracellular domain. (B) Linear schematic representation of AChBP (same colour-code as in A). Aligned sequences of loops 2, 7 and 9 are indicated. Canonical residues are shown in red and conserved residues between α7 and 5HT3A are indicated in green. (C) Representative [3H]epibatidine saturation experiments for AChBP/5HT3A (●) and AChBP(ring)/5HT3A (○) chimeras. Specific normalized duplicate values are shown. (D) Immunofluorescence localization of α7/5HT3A (left), AChBP/5HT3A (middle), AChBP(ring)/5HT3A (right). Transfected cells were assayed for cell surface expression (surface) or for the intracellular expression (permeabilized in the presence of 0.1% Triton X-100) of HA-tagged chimeras. Corresponding ACh-evoked currents are indicated under each construct. (E) Sucrose gradient sedimentation of AChBP(ring)/5HT3A. Each fraction was assayed for [3H]epibatidine binding. Arrow indicates the sedimentation coefficient (10S) of the human α4β2 receptor [20]. Masquer

(A) Left, three-dimensional (3D) structure of AChBP (PBD code: 1I9B) [4] with loops 2, 7 and 9 coloured in blue. These loops form a ring of residues located at the membrane side of the 3D structure of AChBP. Right ... Lire la suite

To address whether AChBP chimeras are targeted to the cell surface, we tagged the human hemagglutinin HA epitope to the carboxy terminus of AChBP/ 5HT3A and AChBP/Gly known to preserve the functionality of the α7/5HT3A chimeric receptor [19]. Given the predicted membrane topology of the receptor, the HA epitope is expected to have an extracellular location that can be recognized by extracellular application of anti-HA antibodies when the receptor is inserted on the cell surface (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence was clearly visible on the cell surface of intact cells expressing α7/5HT3A-HA, but not on those expressing AChBP/5HT3A-HA (Fig. 2D ‘surface condition’) or AChBP/Gly-HA chimeras (not shown). However permeabilized cells showed fluorescence labelling inside the cells (Fig. 2D ‘permeabilized condition’). From these results, we concluded that the chimeras AChBP/5HT3A-HA and AChBP/Gly-HA did not reach the cell surface, in accordance with the lack of both α-BgTx binding sites and of ACh-evoked currents. We therefore reasoned that although high-affinity sites were detected inside the cells expressing the fused proteins, the interface between the binding and the channel domains was not properly formed, thus preventing cell surface expression and channel gating.

Examinations of the crystal structure of the AChBP [5] and of the recent EM structure of the transmembrane domain of the Torpedo nAChR [6] suggest that, in the chimeras, the putative membrane side of the AChBP interacts, through still undefined specific interactions, with elements of the transmembrane domain. The crystal structure of the AChBP shows that the putative membrane side of the protein, defined by the location of the C-terminus, is made of three loops (loops 2, 7 and 9, according to nomenclature of [5], Fig. 2A). Aligned sequences revealed that loops 2 (or β1-β2 loop: Asn-42 to Val-48, AChBP numbering), 7 (or Cys-loop: Cys-123 to Cys-136) and 9 (or β8-β9 loop: Phe-165 to Glu-172) are relatively conserved among the Cys-loop super-family but are not conserved between AChBP and all members of the LGIC (Fig. 2B). Therefore, we hypothesized that restoring homogenous coupling between the two domains would help both the targeting and gating of the chimeric receptor. In the AChBP/5HT3A-HA chimera, we substituted residues within these three loops of AChBP with their 5HT3A counterparts. This created a ‘ring’ of 5HT3A residues serving as an interface of ∼ 10 Å between the AChBP and 5HT3A portions of the chimera, as visualized in the atomic structure of AChBP and in our 3D model of the chimera (Fig. 2A). The AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA chimera showed a four-fold and a ten-fold lower apparent affinity for epibatidine and nicotine, respectively, than its ringless counterparts (

To determine if all loops are required for targeting, we generated chimeras in which only one or two loops in AChBP were changed to 5HT3A sequence. Chimeras with single loop substitutions of either loop 7 or 9 displayed no significant [3H]epibatidine binding (Table 2). Loop 2 substitution showed detectable [3H]epibatidine binding, despite a lack of surface expression, as assayed by immunofluorescence experiments. For all combinations of two loops no significant [3H]epibatidine binding was detected (Table 2). We verified that the lack of sites was due to impaired protein folding and not to lack of protein expression since metabolic labelling of the proteins with [35S]methionine immunoprecipitated with anti-HA mAb yielded bands with the expected molecular weight on reduced SDS-PAGE (data not shown). Hence, only the three-loop substitution displayed cell surface expression, thus suggesting that a synergistic interplay among all three loops is necessary for protein folding and targeting.

[3H]epibatidine binding results for chimeras displaying the different loops combination

| Constructs | loop 2 | loop 7 | loop 9 | dpm/mg1 | Cell surface2 |

| AChBP | AChBP | AChBP | AChBP | 15 100 ± 1600 (3) | no |

| (loop 2) | 5HT3A | AChBP | AChBP | 6000 ± 2000 (4) | no |

| (loop 7) | AChBP | 5HT3A | AChBP | 520 ± 270 (4) | no |

| (loop 9) | AChBP | AChBP | 5HT3A | 490 ± 90 (3) | no |

| (loops 2+7) | 5HT3A | 5HT3A | AChBP | 510 ± 200 (4) | no |

| (loops 7+9) | AChBP | 5HT3A | 5HT3A | 730 ± 120 (4) | no |

| (loops 2+9) | 5HT3A | AChBP | 5HT3A | 630 ± 60 (4) | no |

| ring | 5HT3A | 5HT3A | 5HT3A | 8800 ± 3600 (4) | yes |

| not transfected | 270 ± 230 (3) | – |

1 Specific dpm are indicated. Non-specific values were determined in the presence of 1 mM l-nicotine. For comparison between chimeras binding values were normalized to the concentration of proteins (expressed in mg). Values are means ± SD with the number of determination indicated in parentheses.

2 Cell surface was determined by immunofluorescence experiments on intact cells (see § Materials and methods).

We next checked the functionality of the chimera AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA. No reliable currents were detected either in transfected HEK-293 cells (Fig. 2D) or in injected Xenopus oocytes (not shown) in conditions where significant currents were observed with the α7/5HT3A-HA chimera (Fig. 2D). Removing the HA epitope did not yield functionality for AChBP(ring)/5HT3A (data not shown). To verify that the ring of 5HT3A residues did not prevent function, we generated the homologous ring in the α7/5HT3A-HA. Since loop 2 is fully conserved between α7 and 5HT3A, we substituted only loops 7 and 9 (Fig. 2B). Significant ACh-evoked currents were detected in α7(ring)/5HT3A-HA expressing HEK-293 cells (data not shown). These results thus demonstrate (1) that the AChBP(ring)/5HT3A is not functional, (2) that the ring of 5HT3A residues does not prevent function of the receptor in α7(ring)/5HT3A and (3), thus that some elements in the AChBP chimera prevent gating of the 5HT3A ion channel.

Since AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA is not functional, the possibility exists that unassembled subunits may reach the cell surface without forming functional pentameric receptors. To test this issue, we size fractioned AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA chimera by sucrose density gradient and showed a sedimentation coefficient of ∼ 9.5 S, as expected for a glycosylated pentameric structure [20] (Fig. 2E). Taken together, we conclude that AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA chimera expressed in HEK-293 cells forms a membrane bound pentameric structure with a central ion pore locked in a closed high-affinity state for epibatidine (in the nanomolar range).

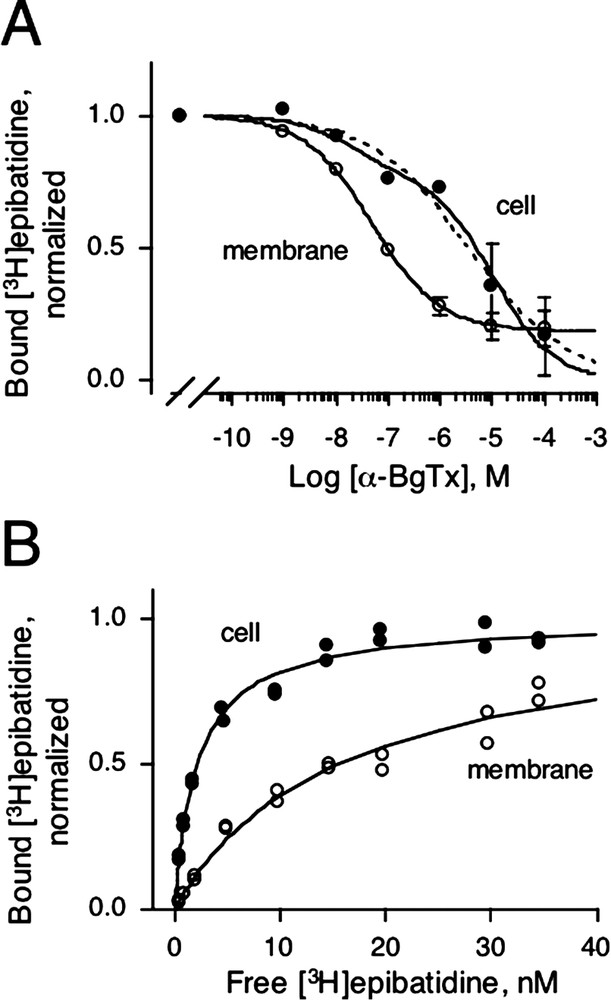

As mentioned above, we report a slight decrease (4- to 10-fold) in agonist affinity between AChBP/5HT3A and AChBP(ring)/5HT3A. This small decrease is probably due to the presence of 5HT3A residues that either directly or indirectly modify the ACh-binding sites located ∼ 30 Å above the interface. An alternative hypothesis would be a conformation change of the entire receptor that consequently changes allosterically the apparent agonist affinity from a high (D state) to a low (B state) affinity. However, the expected changes for a functional receptor in agonist affinities are comprised between 100- to 10 000-fold [21], not consistent with the 4- to 10-fold decrease we found for both epibatidine and nicotine (Table 1). We thus decided to discriminate between these hypotheses by using a compound known to exhibit higher affinity for the B than for the desensitized D state. Three-finger snake toxins block competitively nicotinic receptors [22] and AChBP [23] by targeting the ACh-binding sites preferentially to the B state of the receptor [24–26]. We therefore determined the affinity of α-BgTx for the chimera by measuring on intact cells the displacement of bound [3H]epibatidine by increasing concentrations of α-BgTx. Fitting the data to a one-site Hill equation showed very low affinity (

(A) Displacement of 5 nM bound [3H]epibatidine by increasing concentrations of α-BgTx on intact cells (●) or on membranes (○) for AChBP(ring)/5HT3A. Non-specific binding was determined with either 5 mM ACh or with 5mM carbamylcholine and indicated values are specific binding means ± SD. Dotted and solid lines are fitted curves for one site and two site inhibition models, respectively. (B) Representative [3H]epibatidine saturation experiment for AChBP(ring)/5HT3A on intact cells (●) or on membranes (○). Specific normalized duplicate values to

(A) Displacement of 5 nM bound [3H]epibatidine by increasing concentrations of α-BgTx on intact cells (●) or on membranes (○) for AChBP(ring)/5HT3A. Non-specific binding was determined with either 5 mM ACh or with 5mM carbamylcholine and indicated values are ... Lire la suite

We then tried to shift the equilibrium towards the B state by modifying the chimera itself or the environment.

First, we mutated Arg-11, Arg-148 and Asp-149 to the homologous α7 residue (R11V, R148W and E149S) in AChBP because, as viewed on the crystal structure [5], these residues form potential salt bridges within or between neighbouring subunits. Our hypothesis was that these salt bridges located at the subunit interfaces would stabilize the D state and the disruption of these strong interactions would favour the resting state. However, the triple mutant in AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA did not yield any detectable [3H]epibatidine binding (not shown). Furthermore, we confirmed by immunofluorescence that the triple mutant did not reach significantly the cell surface and likely impaired the folding of the protein.

Second, we prepared membrane fragments from AChBP(ring)/5HT3A-HA expressing cells and determined the apparent affinity for both epibatidine and α-BgTx. When binding assays were performed in membrane preparations the apparent affinity for epibatidine and nicotine decreased by ∼ 5-fold, whereas the proportion of α-BgTx high-affinity sites increased up to 80% (IC50 = 48 ± 1 nM, Fig. 3A and B, Table 1). These results suggest that, after in vitro preparation of the membrane bound receptor, the chimera undergoes discrete allosteric transitions. We conclude that when the receptor is expressed at the cell surface of HEK-293, it is stabilized mainly in a conformation close to the D state of LGICs, but that during membrane preparation the elements that stabilized the receptor are partially or totally lost, thus shifting a new equilibrium towards the B state. Further investigations are needed to identify such elements; one likely hypothesis would be the presence of regulatory proteins such as protein kinase A known to desensitize the 5HT3 receptor through phosphorylation most probably in the cytoplasmic loops [28]. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that water-soluble AChBP, which lacks an ion channel, binds toxins in the nanomolar range in a state different from the state that binds agonists [18].

During the preparation of the present manuscript, Bouzat et al. [29] reported the fusion of Lymnaea AChBP with the rat 5HT3A ion channel into a functional structure. The fusion site is located exactly at the same locus as the present report (at the level of Arg-202). They mutated also the three loops at the putative membrane side of AChBP to human 5HT3 residues; loop 2: (Asn-42 to Glu-47), loop 7: (Cys-123 to Cys-136) and loop 9: (Phe-165 to Glu-172). Their AChBP(ring)/5HT3A transfected in Bosc-23 cells (a highly transfectable modified version of HEK-293 cells) is targeted to the cell membrane, binds α-BgTx and is functional. This finding to some extent contrasts with our data, since we failed to record reliable currents with our chimera. Yet, two differences can explain the contrasted results. First, the so-called ‘ring’ differs by two point mutations, Val48Leu and Ile166Met. These differences while minor may explain the lack of functionality. Second, Bouzat et al. [29] used the rat 5HT3A ion channel, whereas we used the mouse one. Sequence alignment of the two species revealed major differences in the cytoplasmic M3-M4 loop. A six-amino acid deletion and point mutations are present in the rat sequence. Six Ser-phosphorylation sites are predicted in this region for the rat sequence, whereas only two are predicted for the mouse sequence. These differences in the phosphorylation pattern might modify the function of the receptor as observed for the mouse 5HT3 receptor [30]. If that is the case, the pattern of phosphorylations of our chimera probably prevents the receptor from converting substantially into the resting state in intact cells. However, we showed that discrete allosteric transition is possible after membrane preparation for AChBP(ring)/5HT3A and thus that part of AChBP has preserved the structural elements that are necessary for allosteric transitions in agreement with Bouzat et al. [29].

In conclusion, we show in this paper that linear fusion of AChBP with either the cationic 5HT3A ion channel or the anionic glycine ion channel forms high-affinity sites for epibatidine. These results suggest that the AChBP module recognizes any ion channel modules of the Cys-loop super-family, extending the previous observation [4] of autonomous folding of the two main receptor domains: the ligand-binding and channel domains. This finding is of interest since AChBP has probably evolved without the constraint of an ion channel and thus loops 2, 7 and 9 have diverged from their ancestral receptor. Replacement of the AChBP ring (loops 2, 7 and 9) by the 5HT3A counterparts restores a three-dimensional homogeneous coupling between the extracellular domain and the ion channel necessary for targeting to the cell surface. Finally, we showed that the chimeric ring receptor is able to mediate discrete allosteric transitions (i.e. shift the equilibrium in favour to B) that consequently decrease the apparent affinity for both epibatidine and nicotine. Hence, part of AChBP conserved during evolution the capacity to make allosteric isomerizations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the ‘Collège de France’, the ‘Association pour la recherche contre le cancer’, the ‘Commission of the European Communities’ (CEC contracts Nos. 2002-00258 and 2000-00318), and the ‘Association française contre les myopathies’. We thank Drs J. Neyton for experiments with oocytes, P.J. Corringer for discussion, B. Molles for critical reading of the manuscript and H. Betz for providing the human glycine receptor clone. A.T. is the recipient of a fellowship from the ‘Association française contre les myopathies’.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier