Version française abrégée

Le kouprey (Bos sauveli) est une espèce de bovin sauvage décrite en 1937 par le Pr. Achille Urbain. Sa distribution géographique est limitée aux forêts claires du Nord et de l'Est du Cambodge et s'étend légèrement au-delà de ses frontières avec les pays limitrophes que sont la Thaïlande, le Laos et le Vietnam. Il est malheureusement possible que cette espèce soit aujourd'hui éteinte, car aucun spécimen vivant n'a été observé depuis longtemps.

Dans cet article, nous décrivons un spécimen naturalisé qui présente d'étonnantes ressemblances morphologiques avec le kouprey. L'animal est arrivé à la ménagerie du Jardin des plantes de Paris en 1871. Après sa mort, il a été naturalisé au Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, où il a été référencé sous le no 1871-576. Depuis 1931, ce spécimen est conservé au Muséum d'histoire naturelle de Bourges.

Afin de clarifier le statut taxinomique du spécimen de Bourges, l'ADN a été extrait à partir d'un échantillon osseux prélevé sur la mandibule, et deux régions du gène mitochondrial du cytochrome b ont été indépendamment amplifiées et séquencées. Les analyses phylogénétiques indiquent que le spécimen de Bourges est associé à l'holotype du kouprey (MNHN, no 1940-51), et qu'ils sont tous deux proches des autres bovins sauvages d'Indochine, c'est-à-dire le banteng (Bos javanicus) et le gaur (Bos frontalis). Alors que la forme des cornes et la petite taille du spécimen laissent penser qu'il s'agit d'une femelle, l'animal présente une excroissance dans l'entrejambe qui pourrait correspondre à un scrotum. Afin de lever toute ambiguïté sur la détermination de son sexe, nous avons donc utilisé un test moléculaire reposant sur l'amplification par PCR d'un fragment spécifique du chromosome Y. Les résultats ont montré qu'il s'agissait d'un mâle. La comparaison avec les koupreys mâles précédemment décrits dans la littérature révèle d'importantes différences concernant la taille corporelle, la couleur du pelage, ainsi que l'insertion et l'orientation des cornes. Ces différences impliquant des traits phénotypiques fortement sélectionnés par l'Homme en cas de domestication, nous suggérons que le montage de Bourges était en fait un bovin domestique.

Comment expliquer alors que le génome mitochondrial du spécimen de Bourges soit de type kouprey ? Deux hypothèses peuvent être formulées : selon l'hypothèse d'introgression, l'animal proviendrait, soit d'un croisement entre un taureau domestique et une femelle kouprey, soit de la descendance de cette hybridation ; l'hypothèse alternative suggère que le spécimen de Bourges est issu de la domestication du kouprey par les Cambodgiens. Plusieurs éléments permettent de privilégier cette dernière hypothèse. (1) Le montage de Bourges ressemble à des bovins domestiques décrits par des vétérinaires français travaillant en Indochine au début du XXe siècle. Les races les plus proches sont le grand bœuf cambodgien et la race vietnamienne de Thanh-hóa. Ces races partagent de nombreux caractères morphologiques avec le spécimen de Bourges : la taille et les proportions corporelles sont très similaires ; le garrot est puissant, mais ne forme pas de bosse, comme chez les zébus indiens ; le fanon est développé ; la queue est longue et touffue à son extrémité ; lorsque des balzanes blanchâtres sont présentes, la partie avant des canons antérieurs est souvent foncée. En fait, les principales différences entre ces races domestiques et le spécimen de Bourges concernent la couleur du pelage ainsi que la forme et l'orientation des cornes. De telles différences peuvent néanmoins facilement s'expliquer par des variations locales liées à la sélection par des groupes ethniques différents. (2) La plupart des caractères communs aux races domestiques (Thanh-hóa et grand bœuf cambodgien) et au spécimen de Bourges sont aussi partagés avec le kouprey. (3) L'étymologie du mot kouprey est aussi en faveur de sa domestication. Les ethnies de la rive droite du Mékong utilisent le mot Kou-Prey, alors que celles de la rive gauche emploient le mot Kou-Proh. Kou est un mot générique qui désigne un bovin domestique du Cambodge. Prey ou Proh signifie « forêt ». Ainsi, la combinaison de ces deux mots décrit un bovin sauvage localement domestiqué. (4) Les espèces sauvages proches du kouprey ont toutes deux été domestiquées : le banteng en Indonésie, et peut-être aussi en Malaisie et en Thaïlande, et le gaur en Inde, au Myanmar et en Chine. Dans ce contexte, il est difficile de ne pas envisager la domestication du kouprey au Cambodge, notamment sous l'impulsion de la très grande civilisation khmère, sachant, par ailleurs, que l'élevage était pratiqué dans ce pays bien avant que ne soient importées les races européennes ou indiennes.

En conclusion, l'étude de l'animal naturalisé de Bourges révèle que le kouprey pourrait subsister, non pas uniquement à l'état sauvage, mais aussi sous une ou plusieurs formes domestiquées. Il est donc urgent d'échantillonner le cheptel bovin du Cambodge, car si notre hypothèse se vérifie, il conviendra de préserver la pureté de ces races qui, en l'absence de croisement avec des variétés européennes et indiennes, devraient être génétiquement et immunologiquement très intéressantes.

1 Introduction

The kouprey is a wild cattle species (Bos sauveli Urbain, 1937) mainly confined to the open forests of northern and eastern Cambodia. Its distribution follows extensions of these forests into the Dongrak Mountains of eastern Thailand, the southernmost provinces of Laos, and the western edge of Vietnam, along the Cambodian borders [1,2]. Prince Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia designated the kouprey as the country's national animal in 1960. The kouprey is listed by the IUCN as critically endangered [3]. However, no living specimen has been observed for a long time, suggesting that the species may be extinct.

Very few written documents are available on the kouprey, as very few scientists were likely to observe alive specimens. The first document mentioning the existence of the kouprey was written by Dufossé in 1930 [4]. Three years later, Dr Vittoz published a rather complete description of the animal [5]. In 1936, Dr Sauvel captured a one-year-old male calf near the village of Tchep in the northern region of Cambodia, and the animal was sent to the Vincennes zoo, near Paris. While the specimen was alive, it was designated as being the holotype of a new species called Bos (Bibos) sauveli by Prof. Urbain in 1937 [6,7]. The animal died at the age of five years old during World War II [8]. Its complete skeleton and its tanned skin are currently preserved at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris (Muséum national d'histoire naturelle: MNHN).

Many different hypotheses have been proposed in the literature for the taxonomic status of the kouprey. It was originally described as Bos (Bibos) sauveli by Urbain in 1937 [6], the subgenus Bibos indicating close affinities with other wild oxen of Indochina – banteng (Bos javanicus) and gaur (Bos frontalis) [6]. In 1940, Coolidge created a new genus for it, i.e., Novibos, on the grounds of primitive characters by comparison with the more advanced genera Bos (wild cattle and yak) and Bison (American and European bisons) [9]. In 1947, Edmond-Blanc was the first author to consider the kouprey as being an hybrid species produced by the crossing of banteng with one of the three following species inhabiting Indochina: gaur (Bos frontalis), zebu (Bos taurus indicus) and water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) [10]. In 1958, the hypothesis of crossbreeding was followed by Bohlken, who concluded that the kouprey was obtained by hybridisation of the banteng with zebu [11]. Three years later, Bohlken recognised however that the kouprey belongs to a distinct species closely related to the banteng [12]. But in 1963, he concluded that the three skulls of kouprey preserved in the MNHN collections of Paris are castrated domestic cattle [13]. In 1967, all the hypotheses of hybridisation were considered as unfounded by Pfeffer and Kim-San [14], who suggested strong affinities with banteng and gaur, as originally proposed by Urbain in 1937 [6]. More recent morphological investigations have led to different conclusions: in 1981, Groves proposed an association with the aurochs (Bos taurus primigenius) – the wild ancestor of domestic cattle [15], while the cladistic analyses performed by Geraads in 1992 suggested a sister-group relationship with the clade composed of banteng, gaur, and aurochs with its domesticates [16]. In 2004, Hassanin and Ropiquet carried out the first molecular study on B. sauveli [17]. By analysing three different markers (two mitochondrial genes, i.e., cytochrome b and sub-unit II of the cytochrome c oxidase, and one nuclear fragment, i.e., promotor of the lactoferrin), they showed that B. sauveli is closely related to B. frontalis (gaur) and B. javanicus (banteng), as previously proposed by Urbain in 1937 [6] and by Pfeffer and Kim-San in 1967 [14], but the relationships between these three Indochinese species were not resolved. In addition, they listed several nucleotide sites of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (Cyb) gene, which can be used for diagnosing other specimens of kouprey.

Here, we describe a complete taxidermy mount of Bovidae preserved in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Bourges. This specimen was regarded for a long time as being an ordinary domestic ox of Cambodia. During a visit of the Museum of Bourges in October 2003, Prof. Michel Tranier was however intrigued by its strong resemblance to the kouprey. Mr Philippe Candegabe, who was the curator of the mammal collection of Bourges, sent a series of photographs to Dr Pierre Pfeffer, who is one of the few mammalogists knowing the kouprey in the wild. His preliminary conclusions were not categorical because of doubts concerning the fur colour, as well as the shape and orientation of the horns.

In this study, the specimen of Bourges is analysed in details in order to clarify its taxonomic status: the phylogenetic analyses are performed using two fragments of the mitochondrial Cyb gene; the sex of the animal is determined by PCR amplification of a DNA fragment specific to the Y-chromosome; the shape and orientation of the horns are examined by including X-ray images; and the morphology and colour of the specimen are compared with those of wild and domestic cattle found in Indochina.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Material

In 1871, the French Ministry of Navy gave to the MNHN of Paris a living animal described as being a Cambodian ox (bœuf du Cambodge). This animal was apparently kept alive some time in the MNHN zoo named ménagerie du Jardin des plantes. The stuffed specimen was mounted at the MNHN by the team composed of Mrs. Liénard, Perrot, Quantin and Terrier, and referenced as No. 1871-576 in the collections of comparative anatomy (Anatomie Comparée). In 1931, it was given to the Natural History Museum of Bourges (Cher department, France), that is, six years before the scientific description of Bos sauveli by Prof. Urbain [6].

The taxidermy mount of Bourges was compared with the holotype of the kouprey (Bos sauveli), which is conserved at the MNHN (Anatomie Comparée, No. 1940-51 = complete skeleton, No. 1940-1222 = skin). Unfortunately, it was not possible to observe the horn sheaths of the holotype because they have been either lost or stolen.

2.2 Morphological analyses

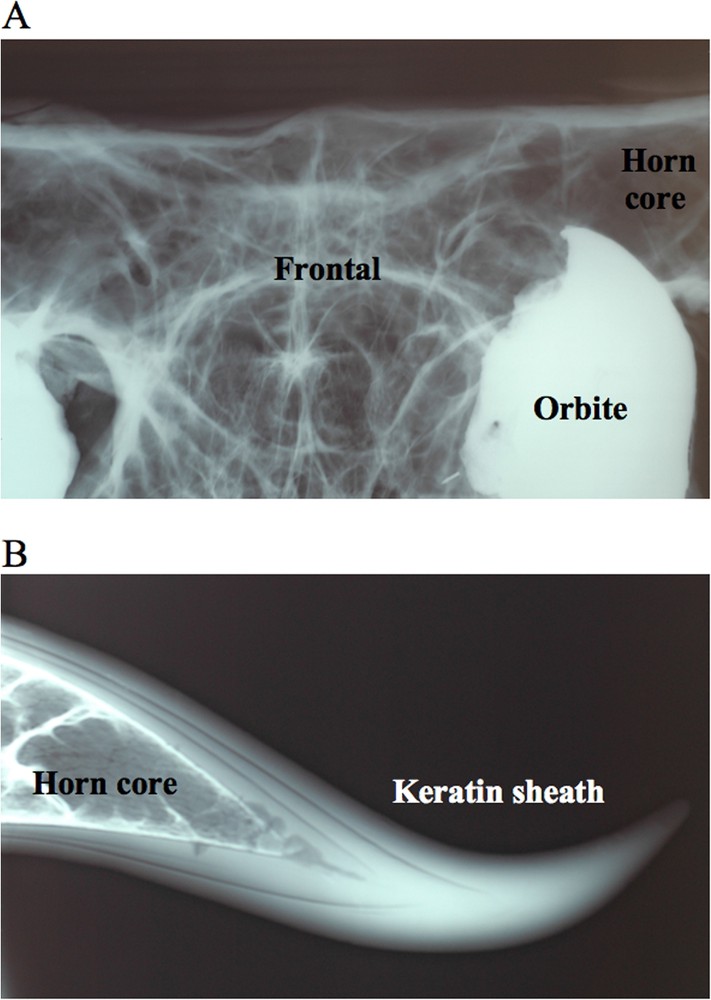

The skeletal elements of the stuffed animal of Bourges were revealed by radiography using a Philips X-ray equipment (model PAC 100), which was graciously lent by the Hospital of Chateauroux (Indre, France). The X-ray images were kindly provided by Mr. Henri-Oscar Ngono and Dr. Xavier Rousseau.

Because UV radiations can considerably fade colours with time, it is a common restoring process to dye the fur of taxidermised animals. For this reason, two tests were performed on two different parts of the animal – flank and leg – in order to determine their original coloration before an eventual restoration: (1) as water is a good solvent, especially for mineral pigments, a piece of wet cotton wool was put on a small surface of both areas; and (2) as alcohol is known to be a good solvent for organic pigments, a piece of cotton wool saturated this time with ethanol was applied on the same areas.

Several measurements were taken on the specimen of Bourges (shoulder height, horn size, tail length, etc.) in order to compare with the data available in the literature for the kouprey, banteng, gaur, and domestic cattle of Indochina. The horns of males were more specifically studied by performing a multivariate analysis on the six following measurements extracted from the study published by Bohlken in 1961 [12]: (1) horn length; (2) distance between the bases of the two horn-cores; (3) circumference at the base of the horn; (4) circumference of the processus cornalis; (5) maximum horn span; and (6) distance between the two horn tips.

2.3 Molecular analyses

2.3.1 DNA extraction

In March 2004, the taxidermist Yves Walter collected a piece of bone on the mandible of the specimen of Bourges. Total DNAs were then extracted at the MNHN (Service de systématique moléculaire) following the procedure developed by Hassanin et al. in 1998 [18]: 1 g of bone powder was incubated for 48 h at 40 °C with a decalcifying solution (EDTA 0.5 M pH 8.5, Tris HCl 10 mM, pH 8.5, SDS 0.5%, Proteinase K 200 μg ml−1); after dialysis, DNA was purified with phenol and chloroform, and then precipitated with ethanol.

2.3.2 Molecular sexing

In 2004, Kageyama et al. developed a simple and precise method for sexing bovine embryos, based on the PCR amplification of S4 – a repeated sequence found on the Y chromosome of Bos taurus [19]. Using a single set of primers, i.e., S4BF (5′–CAA–GTG–CTG–CAG–AGG–ATG–TGG–AG–3′) and S4BR (5′–GAG–TGA–GAT–TTC–TGG–ATC–ATA–TGG–CTA–CT–3′), two PCR products can be amplified simultaneously: (1) a male-specific PCR product, which is 178-bp long and corresponds to S4, and (2) a PCR product of 145-bp long, which is common to both males and females. Here, this procedure was applied for sexing the specimen of Bourges (MNHN, No 1871-576). This method is expected to be particularly useful for sexing old museum specimens, because it avoids incorrect diagnoses due to false-negative amplifications.

2.3.3 DNA amplification and sequencing of the cytochrome b gene

In order to determine the phylogenetic position of the specimen of Bourges, two different regions of the mitochondrial cytochrome b (Cyb) gene were independently amplified by PCR. They were chosen because several diagnostic nucleotides were detected for Bos sauveli in these two Cyb regions [17]. The first fragment is 243-nucleotide (nt) long, and corresponds to positions 163 to 405 in the complete Cyb gene of Bos taurus (accession number V00654). It was amplified with the following couple of primers: L14908: 5′–GCC–TAT–TCC–TAG–CAA–TAC–AC–3′ with H15152 (reverse): 5′–CCT–CAG–AAT–GAT–ATT–TGT–CC–3′. The second fragment is 274-nt long, and corresponds to positions 867 to 1140 in the Cyb of Bos taurus (V00654). It was amplified with the following couple of primers: L15612: 5′–CGA–TCA–ATY–CCY–AAY–AAA–CTA–GG–3′ with H15915 (reverse): 5′–TCT–CCA–TTT–CTG–GTT–TAC–AAG–AC–3′. The PCR conditions were as follows: 3 min at 94 °C; 30 cycles of denaturation/annealing/extension with 1 min at 94 °C for denaturation, 1 min at 52 °C for annealing, and 1 min at 72 °C for extension; and 10 min at 72 °C.

The PCR products were purified using the Montage™ PCR Centrifugal Filter Devices (Millipore). Both strands of all amplicons were directly sequenced using the CEQ2000 Dye terminator cycle Sequencing Quick start kit, and the sequencing reactions were run on a Beckman CEQ2000 automatic capillary sequencer. DNA extraction, amplification and sequencing were repeated twice to check the authenticity of the sequences. The sequences are available in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases under the accession numbers DQ275470 and DQ275471.

2.3.4 Phylogenetic analyses

The taxonomic sample used for this study contains 32 taxa (Table 1). The ingroup is composed of the tribe Bovini, and incorporates 13 different species: the saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), which is the unique member of the subtribe Pseudoryina [20]; five species of the subtribe Bubalina – Bubalus bubalis, B. depressicornis, B. mindorensis, B. quarlesi, and Syncerus caffer –; all the seven species of the subtribe Bovina – Bos taurus, B. frontalis, B. grunniens, B. javanicus, B. sauveli, Bison bison, and B. bonasus. All the sequences found in the nucleotide databases for banteng (B. javanicus; 9 sequences) and gaur (B. frontalis or its synonym B. gaurus; six sequences) were incorporated in the analyses for testing their relationships with B. sauveli. The out-group species include two members of the tribe Tragelaphini – Tragelaphus imberbis and T. strepsiceros – and the two monospecific genera of the tribe Boselaphini – Boselaphus tragocamelus and Tetracerus quadricornis.

Taxonomic sample used for phylogenetic analyses of the cytochrome b gene

| Taxon | Species – common name | Accession numbers |

| Tribe Boselaphini | Boselaphus tragocamelus – Nilgai | AJ222679 [36] |

| Tetracerus quadricornis – Four-horned antelope | AF036274 [36] | |

| Tribe Tragelaphini | Tragelaphus imberbis – Lesser kudu | AF036279 [36] |

| Tragelaphus strepsiceros – Greater kudu | AF036280 [36] | |

| Tribe Bovini | ||

| Subtribe Bovina | Bison bison – American bison | AF036273 [36] |

| Bison bonasus – European bison | AY689186 [17] | |

| Bos frontalis – Gaur | AB077316 [37] | |

| AF348593 [38] | ||

| AF348596 [38] | ||

| AY079128 [39] | ||

| AY689187 [17] | ||

| Y16057⁎ | ||

| Bos grunniens – Yak | AF091631 [20] | |

| Bos javanicus – Banteng | AB077313 [37] | |

| AB077314 [37] | ||

| AB077315 [37] | ||

| AY079131 [39] | ||

| AY689188 [17] | ||

| D34636⁎ | ||

| D82889 [40] | ||

| Y16058⁎ | ||

| Y16059⁎ | ||

| Bos sauveli – Kouprey Holotype No. 1940-51 | AY689189 [17] | |

| Bourges No. 1871-576 | DQ275470, DQ275471 | |

| Bos taurus taurus – Humpless domestic cattle | V00654 [41] | |

| Bos taurus indicus – Zebu | AY689190 [17] | |

| Subtribe Bubalina | Bubalus bubalis – Water buffalo | D88634 [42] |

| Bubalus depressicornis – Lowland anoa | AF091632 [20] | |

| Bubalus mindorensis – Tamaraw | D82895 [40] | |

| Bubalus quarlesi – Mountain anoa | D82891[40] | |

| Syncerus caffer – African buffalo | AF036275 [36] | |

| Subtribe Pseudoryina | Pseudoryx nghetinhensis – Saola | AF091635 [20] |

⁎ Unpublished sequence.

The Cyb gene sequences were analysed for tree reconstruction using Bayesian, Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Maximum Parsimony (MP) methods. MODELTEST 3.06 [21] was used for choosing the model of DNA substitution that best fits our data. The selected likelihood model was the General Time Reversible model [22] with among-site substitution rate heterogeneity described by a gamma distribution and a fraction of sites constrained to be invariable (GTR + I + Γ). Bayesian analyses were conducted under MrBayes v3.0b4 [23]. Different GTR + I + Γ models were applied for each of the three partitions corresponding to the three codon-positions of the Cyb gene. All Bayesian analyses were done with five independent Markov chains run for 2 000 000 Metropolis-coupled MCMC generations, with tree sampling every 100 generations and a burn-in of 2000 trees. The analyses were run twice using different random starting trees to evaluate the congruence of the likelihood values and posterior clade probabilities [24]. Bootstrap percentages (BP) were obtained after 1000 replicates under the fast ML method (BPML) by using the program PHYML 2.4.3 [25], and after 100 replicates under the MP method (BPMP) by applying the weighting procedure based on the products CIex S developed by Hassanin et al. in 1998, where CIex is the consistency index excluding uninformative sites and S is the slope of saturation [26].

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phylogenetic position of the specimen of Bourges

The Cyb gene sequences were analysed with MP, ML and Bayesian methods for tree reconstruction. The trees obtained with the three methods were very similar, and all the topological differences concern weakly supported nodes (Fig. 1). The phylogenetic analyses indicate that the three tribes of the subfamily Bovinae are monophyletic, confirming the results obtained in previous molecular studies [17,20,27]: the tribe Boselaphini includes two monospecific genera of India – Boselaphus (nilgai) and Tetracerus (four-horned antelope) (PPB = 1; BPML/MP = 100); the tribe Tragelaphini is endemic of Africa and is here represented by Tragelaphus imberbis (lesser kudu) and T. strepsiceros (greater kudu) (PPB = 1; BPML/MP = 96/100); and the tribe Bovini groups together all species ranged into the genera Bos, Bison, Bubalus, Syncerus and Pseudoryx (PPB = 0.66; BPML/MP = 49/33). As proposed by Hassanin and Douzery in 1999 [20], the tribe Bovini can be divided in three subtribes: the subtribe Pseudoryina consists in only Pseudoryx nghetinhensis (saola), a species of Indochina described by Dung et al. in 1993 [28]; the subtribe Bubalina associates the Asian buffaloes (species of the genus Bubalus) with the African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) (PPB = 1; BPML/MP = 98/99); and the subtribe Bovina incorporates all species of Bos and Bison found in Eurasia and America (PPB = 1; BPML/MP = 100). Interrelationships between these three subtribes remain unresolved, as indicated by the weak robustness of the nodes (PPB < 0.5; BPML/MP < 50). By contrast, the holotype of the kouprey is robustly enclosed into the subtribe Bovina. This position is in agreement with the recent molecular investigation of Hassanin and Ropiquet [17] and with all morphological studies [6,9,12,15,16].

Systematic Position of the Specimen of Bourges. The tree was obtained from the Bayesian analyses of the mitochondrial cytochrome b gene. All sequences of banteng (Bos javanicus) and gaur (Bos frontalis) found in the GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ databases were included in the analyses. The three values indicated on the branches correspond to Bayesian posterior probabilities greater than 0.5, and the Bootstrap percentages obtained with either Maximum Likelihood or Maximum Parsimony methods. Dash indicates that the node was not found in the Bootstrap analysis. Asterisk indicates that an alternative hypothesis was supported by a Bootstrap percentage greater than 50.

The specimen of Bourges, which is referenced as No. 1871-576 in the MNHN collections, is associated with the holotype of Bos sauveli (MNHN, No 1940-51): (Fig. 1: PPB = 1, BPML/MP = 100/99). Their sequences are very similar, with only 0.4% of divergence, corresponding to two transitions, i.e., A → G in position 876 of the Cyb gene and T → C in position 1043. In addition, they share four exclusive molecular signatures, including two transitions C → T in positions 919 and 1057, and two transversions in positions 360 (A → T) and 361 (C → A). These mitochondrial data suggest therefore that the specimen of Bourges belongs to the species Bos sauveli.

The specimen of Bourges and the holotype of kouprey are grouped with the two other species of wild cattle found in South East Asia, B. frontalis (gaur) and B. javanicus (banteng) (PPB = 0.99; BPML/MP = 78/83). One nucleotide signature is found in the Cyb gene for diagnosing this clade: C → T in position 975. This result is in perfect accord with the view of Pfeffer and Kim-San [14], and is consistent with Urbain, who defined the subgenus Bibos as including the three species of wild cattle found in Indochina [6]. On the one hand, all the six sequences of gaur fall together (PPB = 0.80; BPML/MP = 67/55), and the monophyly of Bos frontalis is diagnosed by one transition G → A in position 694, and one transversion A → T in position 717. On the other hand, all the nine sequences of banteng group together (PPB = 1; BPML/MP = 94/100), and the monophyly of Bos javanicus is supported by four exclusive transitions A → G in positions 84, 123, 531, and 720. In the Bayesian analyses, the kouprey holotype and the specimen of Bourges are the sister group of a clade uniting the banteng and gaur (PPB = 0.55; Fig. 1), but the BP analyses rather suggest an association with the gaur alone (BPML/MP = 35/37). As these nodes are supported by weak PPB and BP values, further analyses with additional molecular markers are needed to decipher interrelationships between kouprey, banteng and gaur.

3.2 What is the sex of the specimen of Bourges?

Most gregarious herbivores evolving in seasonal environments are characterised by an important sexual dimorphism [29]. In the kouprey, as in the banteng and gaur, adult females and males are easily distinguishable on the basis of important differences concerning the shape and size of the horns, body size (weight and shoulder height) and fur colour [2,8,14,30,31].

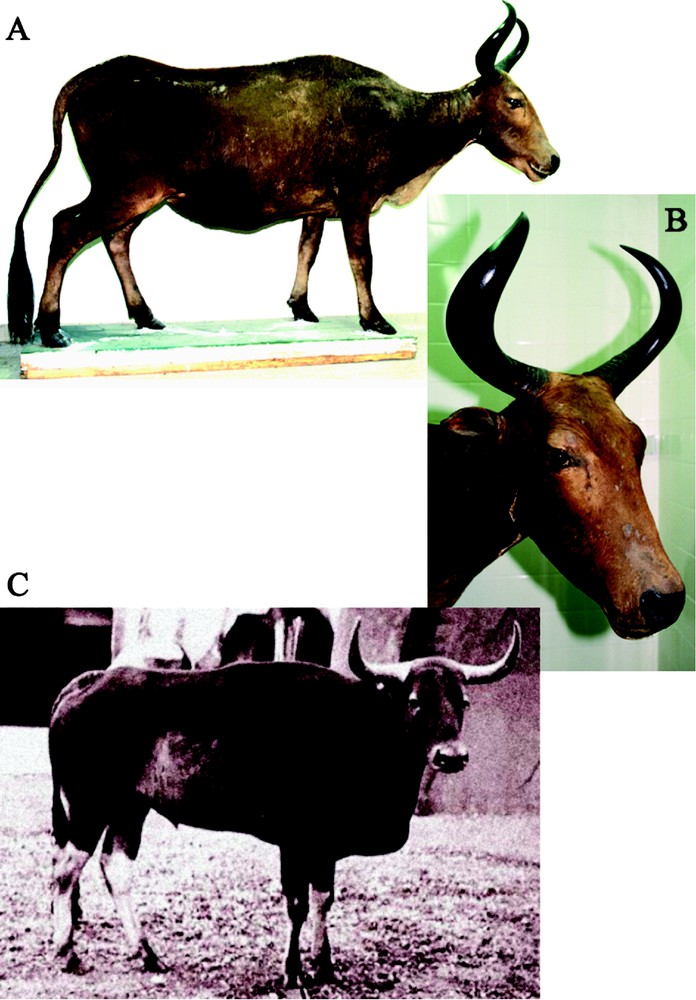

At first glance, the specimen of Bourges may be interpreted as being a female: its shoulder height is only 128 cm, which is very close to the size of adult kouprey females (130 cm) [32]; in addition, the horns are lyriform, and resemble those of kouprey females (Fig. 2). However, a growth in the crotch may be interpreted as a possible scrotum (data not shown). Because of these contradictions in the morphological characteristics, the specimen was sexed using the molecular test developed by Kageyama et al. in 2004 [19]. The results demonstrate that the specimen of Bourges is a male, as two PCR products were amplified simultaneously: (1) a 178-bp-long PCR, which corresponds to a specific fragment of the Y chromosome, and (2) a 145-bp-long PCR product, which is common to both males and females.

Morphology of the specimen conserved at the Natural History Museum of Bourges. A. Right lateral view of the animal. B. Head in three-quarter view. C. Holotype of Bos sauveli (from Urbain, 1937 [6]).

3.3 Morphological comparisons

When firstly described by Urbain in 1937 [6], the kouprey was defined as follows:

“Le boeuf gris est un animal qui diffère du Banteng par sa grande stature puisque certains sujets peuvent atteindre 1 m. 90. D'autre part, son pelage, entièrement gris chez les jeunes et les femelles, est d'un beau noir mat chez les vieux taureaux avec des neigeures aux épaules et sur la croupe. Ces animaux possèdent un fanon très accusé et quatre balzanes haut chaussées. Les cornes sont cylindriques largement écartées, recourbées en avant chez le taureau…Le garrot est puissant, sans déformation musculaire, prolongé en arrière sur la région dorsale. Les oreilles sont légères, fuselées, la queue longue. Les membres plus courts que chez le Banteng sont très fins.”

On the one hand, the specimen of Bourges shares several morphological characteristics with the holotype of B. sauveli: (1) the animal is lighter in build than banteng and gaur; in particular, limbs are shorter and thinner; (2) it possesses a pronounced dewlap, which appears less developed or absent in the banteng and gaur [14]; (3) the tail is 115-cm long, which is much more than for banteng (65–70 cm) and gaur (70–105 cm) [33]; (4) ears are small and tapering; (5) the shoulders are powerful, but without muscular deformation, as observed in the gaur; and (6) lower legs are marked by white stockings, as in banteng and gaur, but the anterior surface of the fore foot is striped by dark hair [6].

On the other hand, the specimen of Bourges exhibits three marked differences with kouprey males concerning the fur colour, orientation of horns and shoulder height. As these characters are differently expressed in young and adult kouprey, it was crucial to estimate the approximate age of the animal. The important development of horns (Fig. 2) and dentition (visible in X-ray images; data not shown) indicate that the animal is not a young calf, but an adult.

The colour of kouprey males evolves with the age of the animal: during the first year, young males are brown, subadult and adult males are grey, and old bulls are dark-brown or black [34]. The colour of the mount of Bourges is brown, and is clearly different from the chocolate colour of the tanned skin of the holotype conserved at the MNHN (No. 1940-1222). As the specimen of Bourges is 134 years old, its original colour may have been however strongly deteriorated, firstly, by important levels of UV radiations and secondly, by the possible addition of mineral and/or organic pigments used for restoring the skin. The left flank and left hind leg (at the metatarsal level) were both tested for the presence of pigments using cotton wool saturated with either water or ethanol. Although we did not find any trace of pigments on the flank, a brown dye, soluble in alcohol, was detected on the left hind leg at the metatarsal level. This indicates that the specimen was restored at least once, suggesting that the fur colour should be considered carefully.

The multivariate analyses performed on six horns measurements of males (Fig. 3) show that the four species of Bos found in Indochina – kouprey, banteng, gaur and domestic cattle – have distinct horns. The horns of Bourges have similar proportions to those of kouprey males analysed by Bohlken in 1961 [12] (Fig. 3A). However, their shape is clearly divergent from other kouprey males (Fig. 3B): the horns rise upward, and then go inside and backward (Fig. 2B), whereas those of kouprey males raise laterally, drop below the base, and then curve upward and backward (Fig. 2C) [9,10,14,34]. These differences did not result from a mistake during the mounting process, as X-ray images indicate a perfect continuity between the frontal bone and horn-cores (Fig. 4A), as well as a perfect interlocking between the horn-core and horn-sheath (Fig. 4B).

Multivariate analyses of six horns measurements. The analyses were performed on the males of four species: ■ Bos frontalis (gaur); ▴ Bos javanicus (banteng); ● Bos sauveli (kouprey); and × Bos taurus indicus (zebu). The six horns measurements were extracted from the study published by Bohlken in 1961 [12]: (1) horn length, (2) distance between the bases of the two horn-cores, (3) circumference at the base of the horn, (4) circumference of the processus cornalis, (5) maximum horn span, and (6) distance between the two horn tips. The multivariate analysis of Log data (A) indicates that the horns of Bourges and Bos sauveli have similar sizes. The multivariate analysis of Log shape ratios (B) shows that the horns of Bourges have a particular conformation, as they are found close to Bos sauveli on the first axis, but divergent and rather close to Bos taurus indicus and Bos frontalis on the second axis.

Radiography of the horns. A. Detail of the frontal bone, showing a perfect continuity with the horn core. B. Detail of the horn, indicating a perfect interlocking between the horn core and keratin sheath.

In adult kouprey males, the shoulder height varies between 170 and 190 cm [6,7,14], which is much higher than the shoulder height of 128 cm measured for the specimen of Bourges. By comparison, the body size of the holotype was 150 cm at the young age of three years and half [7].

Our analyses reveal therefore that the specimen of Bourges presents an original combination of morphological characteristics: on the one hand, it shares several morphological similarities with kouprey males, and in agreement with that, the analyses of Cyb sequences indicate that it is closely related to the holotype of B. sauveli; but, on the other hand, its horns, body size and general coloration are very different from those of wild kouprey males. Interestingly, all these differences concern phenotypic traits that are strongly selected in case of domestication. By its size and general morphology, the specimen of Bourges bears a close resemblance to two Indochinese domestic cattle described by French veterinaries at the beginning of the twentieth century: the Vietnamese race of Thanh-hóa described by Douarche in 1906 [35] and the Cambodian race, named Grand boeuf cambodgien by Vittoz in 1933 [5]. In males of these two races, the horns are however differently shaped and orientated: those of the Cambodian race describe a very unusual circular curve that goes forward, while those of the Thanh-hóa race show a great variety of shapes [5,35]. Horns of domestic cattle are known to be particularly variable in shape and length. We suggest therefore that the specimen of Bourges was not a wild animal, but a domestic ox, as the differences in horns morphology may be explained by local variations due to different selective pressures by ethnic tribes.

3.4 Domestication versus hybridisation

If the specimen of Bourges is a domestic ox, how can we explain that its mitochondrial genome is related to wild kouprey? Two different hypotheses can be formulated: according to the hypothesis of introgression, the specimen of Bourges resulted either directly from the crossing of a domestic bull with a female kouprey, or from the descent of such an hybridisation; according to the alternative hypothesis, the animal of Bourges is a direct descendant from the kouprey, and represents a domesticated form of this wild species. Actually, four elements argue in favour of the domestication of the kouprey in Cambodia:

- (1) several cattle races described in Cambodia and Vietnam are morphologically distinct from races recently imported from India (zebu) or Europe [5,35], suggesting that they have been domesticated locally;

- (2) the specimen of Bourges appears very close to the Vietnamese race of Thanh-hóa [35], and to the Cambodian race, named Grand boeuf cambodgien by Vittoz in 1933 [5]. In addition, they share several morphological features with wild kouprey: shoulders are powerful, but they do not possess the characteristic hump of zebu races; a pronounced dewlap is present; the tail is long with a bushy tip; and they have white stockings on the forefoot, which are marked with dark stripe on the anterior part;

- (3) the etymologic origin of the name kouprey argues also in favour of its domestication: the human populations living on the right bank of the Mekong River used the name Kou-Prey, whereas those on the left bank employed the name Kou-Proh. Kou is a generic name used to indicate the domestic oxen of Cambodia. Prey or Proh signifies ‘forest’, and these words are used to describe a wild animal. Thus, the combination Kou-Prey (or Kou-Proh) indicates a wild ox of Cambodia [8]. It can be however inferred that Prey is used for indicating a wild species that has been domesticated locally, as similarly, the wild elephants are called Damrey-Prey while domestic elephants are called Damrey [8]. By contrast, Cambodians apply a more specific name for other wild species of cattle that have never been domesticated in this country: the banteng is called ‘An song’, and the gaur is named ‘Khtinh’ [5];

- (4) the two other wild cattle of South-East Asia have been domesticated in regions close to Indochina, where the kouprey was not found: the banteng in Indonesia (Bali cattle), and perhaps in Malaysia and Thailand; and the gaur in India, Myanmar and China. Because the livestock farming was known in Cambodia well before the importation of European and Indian cattle breeds, it is likely that the kouprey has been domesticated in this country, notably under the impulsion of the great Khmer civilisation.

To conclude, our study of the stuffed animal of Bourges suggests that the kouprey could remain, not only in the wild, but also in one or more domesticated forms. It is therefore urgent to sample the beef or dairy herds of Cambodia to test our hypothesis. Indeed, if races of domesticated kouprey exist, it will be imperative to avoid any crossing with the European and Indian races, firstly, to preserve the gene pool of the kouprey and secondly, to make the most of their genetic, physiological and immunological characteristics for cattle breeding.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Dr Xavier Rousseau, Henri-Oscar N'Gono, and the Hospital of Chateauroux, for providing X-ray images, to Laurent Arthur and Sandra Delaunay for measurements and photographs. We acknowledge Jacques Cuisin, Christine Lefèvre, Alexis Martin, and Francis Renoult for allowing easy access to the MNHN collections, Patrick Allain, John Brandt, Évelyne Bremond-Hoslet, Jean-Marc Bremond, Sophie Hervet, and Catherine Hoare for bibliography, and the anonymous referee #3 for comments on the first version of the manuscript.