1 Introduction

Human trisomy 21, Down syndrome (DS), is essentially characterized by mental retardation. In addition, the risk of developing hematological and immunological disorders is drastically increased in these patients [1,2]. A mouse model of human trisomy 21, Ts65Dn, has been produced with partial trisomy of chromosome 16, since its distal third is syntenic to the distal end of chromosome 21 and comprises 104 trisomic genes. Ts65Dn mice survive to adulthood and exhibit phenotypic abnormalities that resemble those of DS individuals [3].

We have recently reported that bone marrow cells from adult mice cultured with IL3, IL6 and SCF can be grown in culture over 30 generations, so that over a 4 month period of culture

It has been recently reported that the bone marrow contains progenitors – either hematopoietic or stromal cells – that have the potential of generating a variety of non-hematopoietic tissues such as neural cells, cardiac cells or osteoblasts [5–7]. These data suggested that it might be of interest to explore the properties of bone marrow cells of Ts65Dn mice. Therefore, these cells were put into culture in conditions identical to those previously used for normal mice.

The main result is that the in vitro growth capacity of bone marrow CD34+ cells from Ts65Dn mice is drastically reduced, yet they express a phenotype comparable to that of diploid cells.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Mouse strains

The DS model mice – Ts(1716)65Dn (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) – were used in in vitro and ex vivo experiments. Diploid mice were the littermates of the Ts(1716)65Dn mice. These studies were conducted with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and the Institutional Animal Care Committee at University of Maryland (Baltimore, MD).

2.2 Preparation and experimental conditions of bone marrow cells

2.2.1 Preparation of ex vivo bone marrow cells

Bone marrow cells were obtained and prepared in the same way as reported previously [4]. Briefly, cells were collected aseptically from the femurs of Ts65Dn and diploid adult mice, fixed immediately in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed 2 times in 0.01M PBS (pH7.4) and deposited onto microscope slides by cytospin and stored at

2.2.2 Preparation of in vitro bone marrow cells

The sample of cells from one adult mouse femur was suspended in 10 ml of DMEM (GIBCO Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% FBS with the following supplements: 5 ng ml−1 interleukin-3 (IL3), mouse 10 ng ml−1 interleukin-6 (IL6), 10 ng ml−1 mouse stem-cell factor (SCF) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), and a 1:1000 dilution of 10 μl 2-mercaptoethanol in 2.9 ml of H2O. No matrix, substrate, or feeder cells were added to the liquid medium in the tissue-culture flasks. The medium was distributed into two T75 tissue-culture flasks to grow the cells at 37 °C in humidified 10% CO2 in air. Passaging and feeding the cells with addition of 5 ml of fresh medium to each flask were usually done two times a week. Only the floating cells were passaged, leaving behind all the attached cells such as bone marrow stromal cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages, etc. Floating cells were subcultured in 50% conditioned medium from the previous culture and 50% fresh medium at

2.3 Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemical studies were performed on ex vivo and in vitro bone marrow cells. Paraformaldehyde-fixed cells on microscope slides were treated with 0.25% Tween 20 for 3 min at 21°C, washed three times in PBS, and analyzed by standard immunocytochemistry methodology with the following antibodies: primary antibodies against CD34, Sca-1 (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), cKit (Cymbus Biotechnology, Chandlers Ford, UK), CD38 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), Ki67 (Novocastra Laboratories Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). Additionally, for cultured cells staining the following antibodies were used: AA4.1, CD45 (BD Pharmingen), B220 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), F4/80 (Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA). After 1-h incubation in blocking buffer (0.01 M PBS, pH7.4, 10% Normal Goat Serum, 0.3% TritonX-100) with primary antibody the cells were washed three times in 0.01 M PBS buffer and then treated with the secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature. The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa Fluor 546 F(ab′)2 goat anti rabbit IgG H + L (Molecular Probes Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), Fluorescein (FITC) AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rat IgG (H + L), Fluorescein (FITC)-labeled F(ab′)2 goat anti-rabbit, Rhodamine conjugated affinity Pure F(ab′)2 goat anti-rat IgG (H + L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). After three washes in 0.01 M PBS (pH7.4) the cells were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlington, CA). In each labeling, we used the secondary antibody alone as a control.

2.3.1 TUNEL assay

Fixed cells from diploid and Ts65Dn were processed with cleaved caspase 3 (c-caspase 3) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) and TUNEL by using an apoptosis detection kit (Roche Bioscience) following the manufacturer protocol. Cleaved caspase 3 antibody was used according to the immunocytochemical method described above.

2.3.2 BrdU labeling

To label mitotic bone marrow cells, 10-week-old cultures were incubated with one pulse of BrdU (final concentration 10 μM). After 5 h of incubation the cells were collected and prepared for immunolabeling as described above. Before labeling with the primary antibody the antigen retrieval was performed on the cultured cells using Retrievigen A (pH 6.0) (550524, BD Pharmingen) for 45 min. Then, a standard immunocytochemical protocol was carried out using anti-BrdU (1:100, 347580, Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) as a primary antibody and goat anti-mouse biotinylated IgG (1:300, BA-9200, Vector Laboratories) as a secondary antibody. The labeling was detected with DAB chromogen (Vector Laboratories).

2.3.3 Labeling of mast cells

Mast cells from various ages were labeled in two different ways. For histochemical analysis, cells were spun down, fixed in methanol, stained with 0.1% toluidine blue and then washed in PBS. For living cells we used FITC-conjugated anti-FcɛRIα antibody (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) diluted in 0.1 M PBS (pH7.4) with 1% BSA, in a final concentration 1:200. After 30 min of incubation, the cells were washed three times in PBS.

2.4 Western blot analysis

Proteins from cultured CD34+ cells were separated by 10, 12, and 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as reported [4], and analyzed using specific antibodies against: cKit (CBL1359, Cymbus Biotechnology, Chandlers Ford, England), IL3R, IL6R (SC 681 and SC 13947, respectively, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), c-caspase 3 and p53 (9661S and 2524, respectively, Cell Signaling Technology).

3 Results

We have previously reported that bone marrow CD34+ cells from various diploid strains of mice are highly proliferative in culture and can grow as a pure population over 30 generations [4]. In the present study we have investigated the growth capacity in culture of bone marrow cells from TS65Dn mice in parallel with that of diploid littermates. Starting with the same number of bone marrow cells in diploid and Ts65Dn (

(A) Growth curves of bone marrow cells of adult diploid (▵) and Ts65Dn (●) mice. In diploid cell cultures, the number of proliferating cells is 6–7 logs greater than in Ts65Dn cell cultures. (B, C) Cultures of bone marrow cells from diploid and Ts65Dn mice. All cells are CD34 positive and are labelled with DAPI (blue). (B) Mitosis detected by anti-BrdU and anti-Ki67 antibodies. The proportion of proliferating cells in Ts65Dn mice is significantly reduced. Graphs represent the percentage of BrdU+ (B1) and Ki67+ (B2) of CD34+ cells cultured for 6, 8 and 10 weeks. The values represent mean ± SEM. (C) Apoptosis of CD34+ cells detected by nuclear DAPI staining and anti-c-caspase 3 and anti-p53 antibodies. The number of apoptotic cells is significantly higher in Ts65Dn cultures than in diploid. White arrows point to apoptotic nuclei. (C1) Graph represents the percentage of cells expressing c-caspase 3 in CD34+ cultures from diploid and Ts65Dn mice at 6, 8 and 10 weeks. In Ts65Dn cultures, the number of apoptotic cells is much higher than in diploid cultures. The data represent mean ± SEM, c-caspase 3 stands for cleaved caspase 3. (C2) Western blot analysis shows the presence of p53 in CD34+ cells of Ts65Dn cultured for six weeks. TA, TC – individual trisomic mice, DA, DE – individual diploid mice. (D) Phenotypic markers in 10-week-old cultures of CD34+ cells from diploid and Ts65Dn mice. Masquer

(A) Growth curves of bone marrow cells of adult diploid (▵) and Ts65Dn (●) mice. In diploid cell cultures, the number of proliferating cells is 6–7 logs greater than in Ts65Dn cell cultures. (B, C) Cultures of bone marrow cells ... Lire la suite

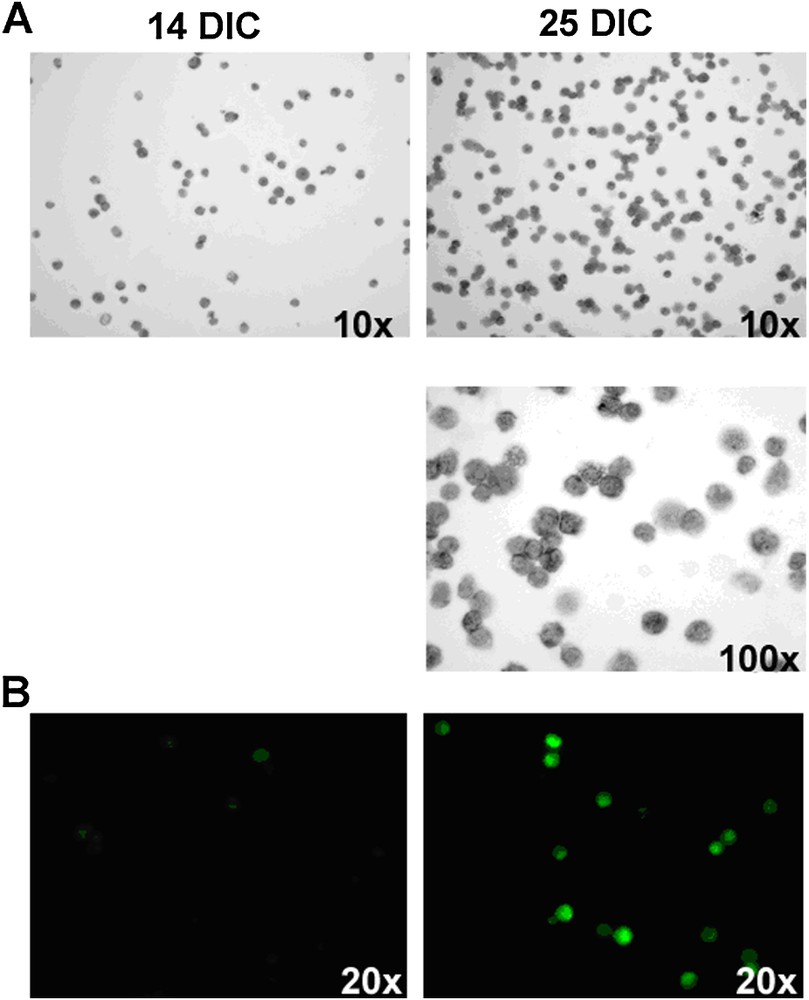

14 and 25 day-old cultures of bone marrow cells stained with (A) toluidine blue and (B) anti-FcɛRIα antibody. The number of cells containing grey granules or expressing FcɛRIα receptors, specific for mast cells, greatly increases between 14 and 25 DIC. DIC: Days In Culture.

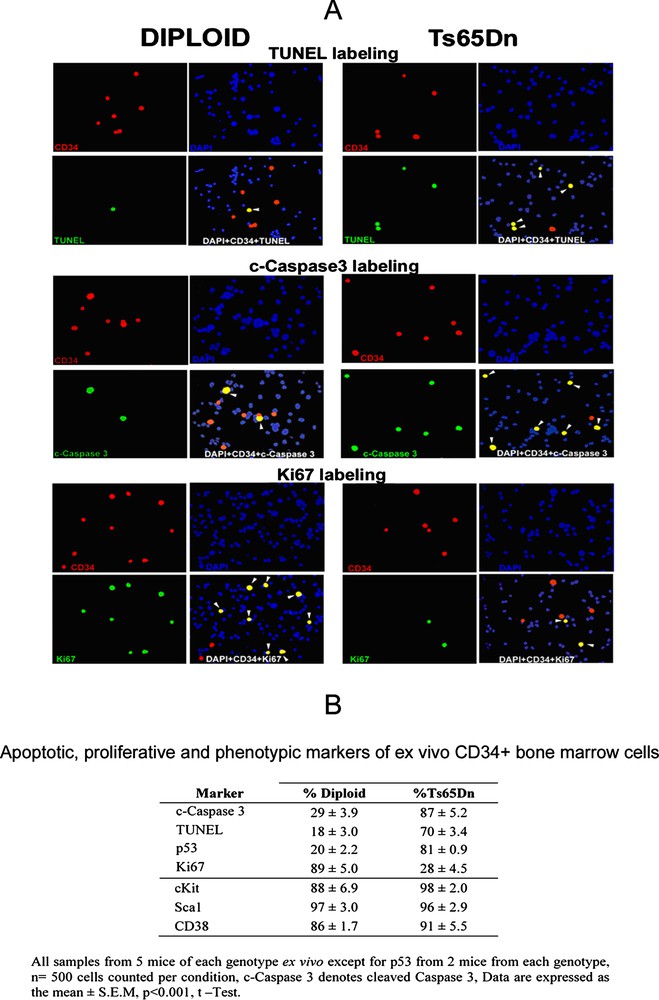

Taken together, these data indicate that the populations of the bone marrow CD34+ cells in culture from trisomic and diploid mice are comparable, except for their growth capacity, which is drastically reduced in cells from trisomic mice. Therefore we investigated which mechanisms could account for the low growth of CD34+ cells from Ts65Dn mice. One obvious possibility is that the cells lack receptors for the cytokines used in these experiments. However, as shown in Fig. 3, receptors for IL3 and IL6 were detected at comparable levels in CD34+ cultures from diploid and trisomic mice. We then asked the question whether CD34+ cells from ex vivo bone marrow of trisomic mice expressed markers which may account for the defective growth capacity of these cells. The percentage of ex vivo bone marrow CD34+ cells from diploid and Ts65Dn mice was comparable (

Western blot analysis of IL3 and IL6 receptors in Ts65Dn and diploid cultures. Equal amounts of total cell protein were added as shown by the level of c-kit expression DC: individual diploid mouse; TA TB, TC: individual trisomic mice.

(A) All cells are stained with DAPI (blue), CD34 positive cells are red, and cells stained for TUNEL, c-caspase 3 or Ki67 are green, yellow cells are triple stained with DAPI, CD34 and TUNEL, or c-caspase 3, or Ki67 (white arrowheads). (B) The percentage of cells double labeled by CD34 and c-caspase3, or TUNEL, or p53 is significantly higher in Ts65Dn mice. Conversely, the percentage of cells double labeled with CD34 and Ki67 is much higher in diploid mice. In contrast, the hematopoietic markers: c-Kit, Sca1 and CD38 label the vast majority of CD34+ cells both in diploid and trisomic mice. Masquer

(A) All cells are stained with DAPI (blue), CD34 positive cells are red, and cells stained for TUNEL, c-caspase 3 or Ki67 are green, yellow cells are triple stained with DAPI, CD34 and TUNEL, or c-caspase 3, or Ki67 (white ... Lire la suite

4 Discussion

The main finding of this report is that a distinct population of bone marrow cells characterized by expression of the CD34+ molecule exhibits a marked decrease in in vitro growth capacity in mice which have a triplication of the chromosome homologous to human chromosome 21, as compared to diploid mice. In this chromosome, the region syntenic to the human chromosome 21 contains 104 triplicated genes. Which product(s) of the trisomic genes [9] are expressed the apoptosis of bone marrow CD34-positive cells and leads to their drastically decreased growth capacity? Among them, some are known to be involved in cell cycle and apoptosis, such as Sod-1, an antioxidant enzyme, whose overexpression leads to a hypoplastic thymus and bone marrow abnormalities [10] or the transcription factor Runx1 [11] which codes for AML-1, involved in hematopoiesis regulation and also in DS leukemias [12]. We have also shown that the apoptotic p53 protein is increased in trisomic CD34+ cells, possibly as a result of overexpression of the transcription factor ets-2, which binds to the promoters of p53 gene as well as to that of p21, a regulator of cell proliferation [13–15]. The most surprising result of this study is that the presence of apoptotic markers is strictly restricted to CD34+ cells. We may speculate that the CD34 protein or associated proteins contribute to a transduction process involved in an apoptosis pathway. It will be therefore of interest to compare expression of above genes, among others, in the homogeneous population of cells expressing CD34+ versus CD34− cells and as well to measure the effect of trisomic gene expression on the pattern of non-trisomic gene expression in CD34+ cells. It has already been shown in Ts65Dn and in another model of Down syndrome-Ts16 mice, that there is increased apoptosis in the nervous system in the hippocampus [16] and cortical neurons [17], thymus [2,4,18] and germ cells [19]. Indeed, it has been reported that during the development of the neocortex of the Ts16 mouse, as compared to controls, a smaller proportion of progenitors that exit the cells cycle, a longer cell cycle, and a reduced growth fraction, as well as an increase in apoptosis [20]. The trisomy model of stem-cell proliferation may yield the genetic basis of a general mechanism for control of the balance of cell mitosis and apoptosis. Finally, it may be of interest that the slowly growing Ts65Dn CD34+ cells in the culture display a mast cell phenotype because of the role of these cells in inflammatory and immunoregulatory processes [21].

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. A. Costa from Eleanor Roosevelt Institute of University of Denver for providing Ts65Dn and diploid mice. We also would like to thank S. Clark for help with analyzing in vitro data and T. Wright for maintaining cultures, Dr. P. Yarowsky for discussion, and Dr. D. Ogden for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review (D.T.) and the ‘Fondation Jérôme-Lejeune’, France (B.P.).