1 Introduction

Trees of the genus Cecropia (Cecropiaceae) are common pioneer plants in disturbed Neotropical landscapes. Most species of Cecropia are myrmecophytes, or plant-ants, that shelter their resident ants in their hollow trunk and branches (domatia) and provide them with food resources in the form of food bodies or Müllerian bodies produced by specialized pads of tissue (trichilia) situated at the base of leaf petioles. The most common resident ants belong to the genus Azteca (Dolichoderinae) which exhibit a wide variety of arboreal nesting habits, including being obligate inhabitants of a variety of myrmecophytes. In exchange for the lodging and the food they receive, Azteca ants protect their host Cecropia against herbivores, remove encroaching vegetation, and provide minerals [1–3].

Myrmecophytic Cecropia have long been thought to form associations only with Azteca ants, but certain species are associated with ants of the genera Pachycondyla (Ponerinae) and Camponotus (Formicinae) [3]. For example, 64% of Cecropia purpurascens () were colonized by ants of four species, of which Azteca alfari (Dolichoderinae) and Camponotus balzani (Formicinae), were found at a higher frequency [4]. However, only one colony of any given species will inhabit the plant at any given time as these ants are highly territorial.

In most ants, including ground nesting, arboreal foraging species, territoriality contributes to the defence of spatiotemporally stable food resources and to the trails towards these sources. Their territory area is often correlated with colony size, a major determinant of competitive ability [5]. This is also true for plant-ants as in the Azteca-Cecropia associations, as larger trees can host larger colonies [4] that would be harder to dominate because they have more individuals available to patrol a plant and recruit defenders [1].

Camponotus blandus (Formicinae), like some other species of the genus [6], is a ground nesting-arboreal foraging species not known to colonize Cecropia obtusa (Cecropiaceae). Yet, C. blandus workers have been observed to patrol Cecropia trees during the day and triggering violent conflicts with the resident A. alfari. Other Camponotus species [7,8] have also been reported to regularly patrol trails and attack alien conspecifics and other ant species, but it is often difficult to distinguish territorial aggressiveness from predation, as the same behaviours can occur in both cases [9].

This study was conducted to determine if the C. blandus major workers frequently observed on Cecropia obtusa were (1) hunting A. alfari workers; (2) exploited Müllerian bodies; or (3) if their presence corresponded to a type of territoriality. We therefore determined the activity rhythms of these species, the frequency of their encounters and the behaviours in which they resulted.

2 Materials and methods

Fieldwork was done in Petit-Saut, French Guiana (5°03′N; 53°02′W), and data were collected in July 2006, at the end of the rainy season. Both species studied appear to be diurnal [10–12], as neither species was present when we sampled before daybreak, and therefore observations were restricted to daylight hours.

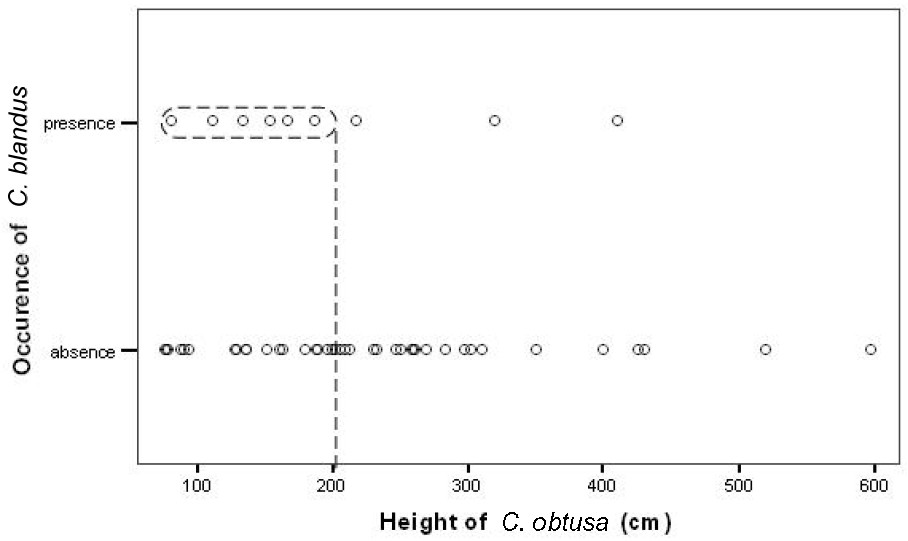

Because tree height is suspected to be correlated with Azteca colony size, it can be expected that fewer C. blandus would be successful in foraging on larger Cecropia trees sheltering large colonies [4]. Preliminary observations were therefore done on 51 trees ranging from 0.5 to 6 m in height and sheltering colonies of A. alfari to determine if their size was correlated with the presence or absence of C. blandus and to select for an intermediate tree height with increased probability of encounters between A. alfari and C. blandus for further observations. Binoculars were used to scan the trees and the trunks of taller trees were anchored in a bent fashion to enable easy scanning of single foraging ants.

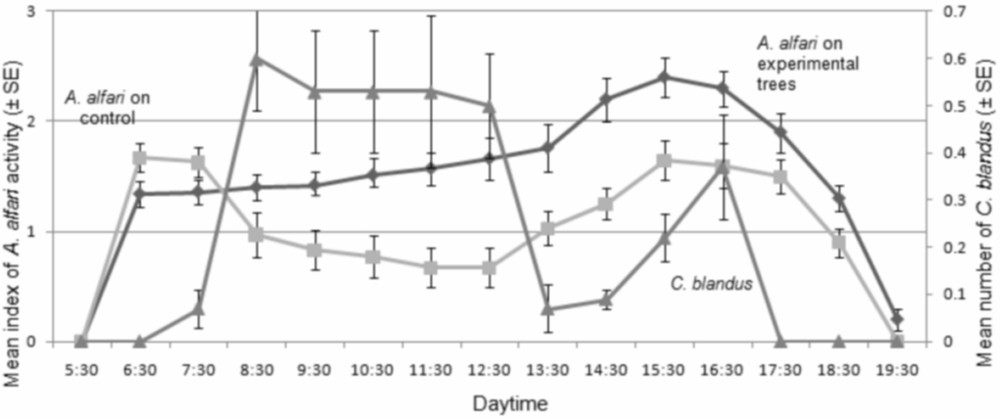

Isolated saplings (ranging from 1 to 1.75 m in height) of Cecropia housing colonies of A. alfari were tagged. Selected trees were separated by a distance of at least 10 m, ensuring that they were far enough apart to constitute independent samples. An experimental lot corresponded to 30 trees situated on the territory of C. blandus colonies, while 20 other trees were not and formed a control lot. For both the experimental and control lot, series of 2-min scans were conducted by the three authors on each tree over a 4-day-long period until every hour between 5h30 and 19h30 had been covered once for a total of 12 hours. During each shift, each individual stem was searched for ants. The activity level of A. alfari workers on trees was estimated on a scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0: total absence of workers; 1: up to ten workers; 2: 10 to 50 workers; 3: more than 50 workers). On experimental trees the number of C. blandus individuals was directly recorded in the same scans as with Azteca.

3 Results

Although we noted a trend of fewer C. blandus workers, none of which were observed walking in a file or marking trails, with increasing height of Cecropia trees inhabited by A. alfari, the difference was not significant (seven of the 24 sampled trees of less than two meters scored at least one C. blandus worker versus three of the 27 sampled trees of more than two meters; Statistica software; Fisher's exact-test; ; Fig. 1). Nevertheless, almost all C. blandus major workers were seen trekking up larger trees before turning back at mid-point, without having encountered any A. alfari individuals.

The presence or absence of Camponotus blandus on saplings of Cecropia obtusa (N=51) (ranging from 0.5 to 6 m in height) inhabited by Azteca alfari.

The activity pattern for A. alfari was initiated abruptly at dawn. It declined on the experimental trees while that of C. blandus increased (up to five workers on a tree) at mid-morning; this was not the case on the control trees (Fig. 2). The maximum activity level for A. alfari was noted during the afternoon when the production of Müllerian bodies is at its highest [13], but due to the residual activity of C. blandus workers, A. alfari workers were more active on control trees than on experimental trees.

Mean activity level (±SE) of Azteca alfari on control (absence of Camponotus blandus in the area (N=20)) and on experimental (N=30) Cecropia obtusa of the same size (1–1.75 m in height; 20 and 30 trees, respectively) likely to be on the territory of a Camponotus blandus colony, with the average number of C. blandus major workers per tree on experimental trees (mean activity level of C. blandus (±SE)) during observations (N=700).

Although C. blandus workers were absent from most trees at any given time, when present (up to five individuals), they appeared to patrol the focal trees and on several occasions one to three workers stood guard in front of the domatia entrances (near the base of the leaf petiole at the top of the tree) where the A. alfari workers had retreated, preventing them from exiting. However, colonies of A. alfari have a large number of small, aggressive workers which can occasionally bite the legs of the larger C. blandus and spray defensive compounds at them. When confrontations did occur (), C. blandus workers were sometimes rapidly overcome and were even chased off the tree on two occasions, but never killed. Even when killed, A. alfari workers, which outnumbered the C. blandus and whose corpses littered the trunks, were never retrieved by C. blandus (a total of 24 A. alfari workers were killed during the nine confrontations).

4 Discussion

Territoriality varies among ants, with some species protecting only their nests or their resources, while others, including plant-ants, establish absolute territories by excluding nearly all other ants ([7,14,15] and references therein). Also, most investigated ant species establish territories that secure access to food resources, and it was suggested that spatial and nychtemeral distributions of the feeding activities among different sympatric species limit competition for resources [16].

Because tall trees can host larger Azteca colonies ([4]; pers. obs.) more A. alfari workers were observed patrolling their host tree, eventually recruiting numerous nestmates when encountering alien ants [1]. However, although the number of observed C. blandus decreased with increasing tree size, the difference was not significant. In fact, the difference is qualitative as when exploring large trees, C. blandus workers frequently turned back at mid-point on the trunk without having encountered any A. alfari workers. They are likely deterred by the concentration of chemical signals situated at the territorial boundaries of the large A. alfari colonies (see also [2]).

The activity pattern described for A. alfari is consistent with previous observations, commencing abruptly at dawn with a mid-day plateau or depression and a maximum in the afternoon concomitant with the production of Müllerian bodies [13]. The number of C. blandus individuals on the trees increased gradually to a maximum during mid-day (see also [11]). Furthermore, because C. blandus is mostly active before A. alfari is at its maximum activity level, it is possible that there is a general trade-off between behavioural dominance and thermal preference in these ant species. Indeed, C. blandus has been shown to be most active at ambient temperatures of 32–34 °C [17], but it is unclear whether the maximum of activity of A. alfari is due to thermal preference, an internal clock related with the production of Müllerian bodies [10,13], or, less likely as the number of cases is reduced, interactions with sympatric ants.

The blocking of the domatia entrances was also noted for certain Neotropical social wasps; while one wasp blocks the domatia entrance of a Cecropia to prevent the Azteca from leaving, its nestmates gather Müllerian bodies [18]. However, C. blandus was never observed collecting Müllerian bodies on Cecropia as do other ground-nesting ants, such as Pheidole fallax and Solenopsis saevissima [18]. Because the blocking of the Cecropia domatia entrances by C. blandus workers was not related to a strategy permitting to gather Müllerian bodies, nor the predation of A. alfari workers, the observed agonistic interactions appear to correspond only to interspecific territoriality.

This territorial response is surprising and this apparent departure from optimal foraging might stem from a behavioural constraint of this species' territorial aggressiveness. Indeed, it seems that C. blandus workers are “trapped” by their territoriality because they are not rewarded while blocking Cecropia domatia entrances and because A. alfari workers never forage on the ground [3] and so never compete with them. It is probable that the perception of A. alfari landmarks is at the origin of this behaviour, with a threshold above which C. blandus workers do not try to stay on Cecropia, such as is the case for tall trees hosting large A. alfari colonies. Ants “trapped” by chemical signals were reported for workers of plant-ant species that, although not rewarded, patrol the young leaves of their host myrmecophyte. In this case the most vulnerable parts of the plants are well protected through a “sensory trap”, generally a brood odour-mimicking chemical at the origin of this attractiveness [19].

In fact, C. blandus are generalists and, when A. alfari is absent, may exploit resources (Hemipterans, invertebrate prey) other than Müllerian bodies. A general territorial behaviour may be maintained from benefits related to several other ant species not studied in the present work (i.e., species being important competitors and engaging in frequent encounters with C. blandus). That is, realized costs of hostility against A. alfari may very well be insignificant compared to benefits from keeping away other species, including Azteca species not associated with myrmecophytes. Therefore, aggressive behaviours observed during this study may be a maladaptive consequence of C. blandus territoriality on trees occupied by other ant species and warrants further investigation.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Philippe Cerdan and the staff from the Laboratoire environnent de Petit Saut (French Guiana) for providing the facilities and the equipment for this study. We are grateful to Andrea Dejean for assistance with local accommodations. This work was supported by the Programme Amazonie of the French CNRS and complies with the current laws of the country in which they were performed.