1 Triacylglycerols as widespread energy storage compounds

Triacylglycerols (TAGs) are esters of glycerol in which fatty acids are esterified to each of the three hydroxyl groups of the glycerol backbone. The carbons in fatty acids being highly reduced, the oxidation of TAGs releases twice as much energy as the oxidation of other energy storage compounds like carbohydrates or proteins [1]. This may explain why TAGs are synthesized in many animal and plant tissues where they act as an energy reserve.

In mammals, the liver is crucial for controlling energy homeostasis. In fasting conditions, the liver produces glucose through glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis to meet the energy requirements of other tissues ([2] and references therein). On the contrary, after absorption of a high-carbohydrate diet, it is a major site for glucose uptake and storage in the form of glycogen. When hepatic glycogen concentrations are restored, the glucose delivered into the portal vein is converted in the liver into TAGs through de novo lipogenesis (Fig. 1). Most of these lipids are packaged into very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) particles, exported, and ultimately stored as TAGs in adipose tissue. Yet, TAGs can also be stored as lipid droplets within the hepatocytes or even hydrolyzed and the fatty acids released channeled toward ß-oxidation. Excessive accumulation of TAGs within the hepatocytes is one of the main characteristics of hepatic steatosis, a pathological pattern that is now regarded as a component of the metabolic syndrome [3]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which is emerging as the most common chronic liver disease in the Western countries, describes a large spectrum of liver histopathological features including simple steatosis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma [4]. NAFLD being associated in the vast majority of the cases with obesity in the human population, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes, it has become a major public health issue. Although the molecular mechanism leading to hepatic steatosis is complex, the study of lipogenesis in the liver of animal models has brought significant insights into our understanding of this pathology. De novo lipogenesis is regulated by multiple hormonal and nutritional signals [5]. The absorption of carbohydrate in the diet is accompanied not only by changes in glucose concentrations but also by changes in the concentrations of pancreatic hormones like insulin. Two independent, although partially redundant, signaling pathways are triggered by glucose and insulin, respectively, and are critical for induction of lipogenic enzyme genes [6].

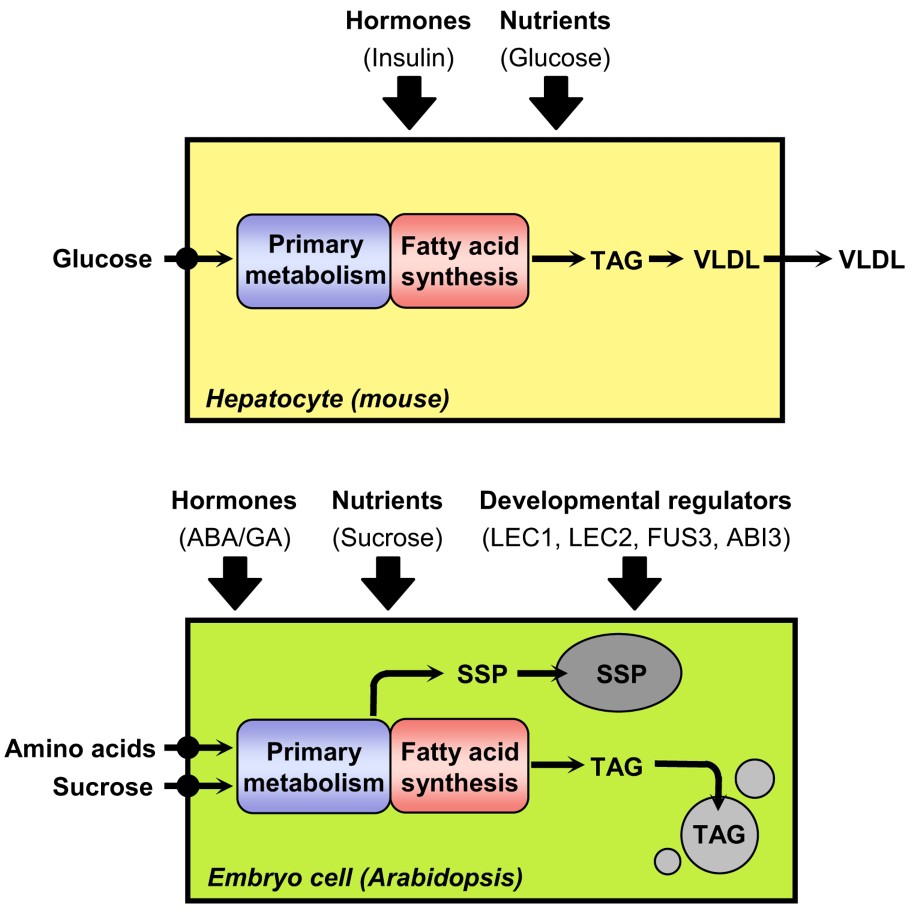

Triacylglycerol synthesis in hepatocytes of mice and in embryo cells of Arabidopsis. For each biological system considered, nutrients provided to the cell for the synthesis of fatty acids are indicated on the left side of the scheme. Factors known or suspected to induce lipogenesis are presented above the schematized cells. ABA, abscisic acid; GA, gibberellic acid; SSP, seed storage proteins; TAG, triacylglycerol; VLDL, very low density lipoproteins.

Many plant species accumulate TAGs in their developing seeds to fuel post-germinative seedling growth until seedling photosynthesis can be efficiently established. In the model plant Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), which is closely related to oleaginous species like rapeseed (Brassica napus), both seed storage proteins (SSPs) and oils are synthesized and accumulated in the zygotic tissues of the seed, namely the embryo and the endosperm [7,8] (Fig. 1). In Arabidopsis, seed development comprises two major phases: embryo morphogenesis (EM) and maturation. During EM, the embryo acquires the basic architecture of the plant through a series of programmed cell divisions [9]. During the maturation phase, which is characterized by a strong increase in seed dry weight (DW), the embryo accumulates high amounts of SSPs and oils, the biosynthesis of these compounds relying on the import of sucrose and amino acids from maternal tissues. In mature dry seeds, SSPs and TAGs account for 30–40% of seed DW each, these compounds being stored in specialized organelles called protein storage vacuoles and oil bodies, respectively. TAGs produced in seeds being structurally similar to long chain hydrocarbons derived from fossil carbon, plant oils represent potential alternatives to hydrocarbon-based products [10]. Oilseeds also provide a unique platform for the production of high-value fatty acids that can replace oceanic sources of specialty chemicals and aquaculture feed [11,12]. Yet, the economic viability of using plant oils as renewable resources being critically dependent on yield, an urgent need to decipher the regulation of lipogenesis in maturing oilseeds has been put forward. The regulation of seed maturation and storage compound accumulation requires the concerted action of several signaling pathways that integrate information from hormonal and metabolic signals and from genetic programs [13,14]. The molecular mechanisms involved in the control of maturation-associated processes by hormones (abscisic acid-to-gibberellic acid ratio) and/or metabolic signals (sucrose) remain to be fully elucidated. The genetic programs triggering seed maturation are better characterized. Four loci have been identified in Arabidopsis, namely FUSCA3 (FUS3), ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE3 (ABI3), and LEAFY COTYLEDON1 and 2 (LEC1 and LEC2), which control a wide range of seed-specific characters and act as master regulators of seed maturation. FUS3, ABI3, and LEC2 belong to the B3 family of plant transcription factors [15–18], whereas LEC1 encodes a NFY-B factor [19]. Functions of these genes are partially redundant. They act in an overlapping manner and define an intricate regulatory network that exhibits cross-talks with hormonal and metabolic signaling pathways [14].

2 Metabolic networks of triacylglycerol biosynthesis

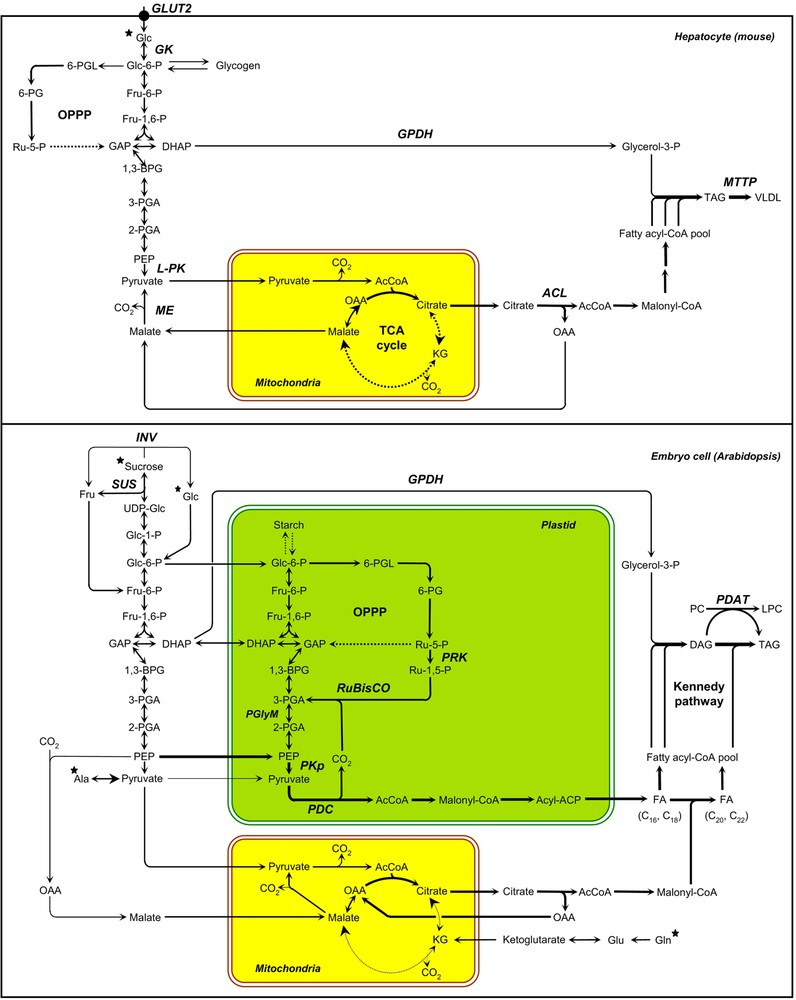

In the liver of mammalians, de novo lipogenesis is mostly dependent upon glucose delivery to the hepatocytes. Among the different hexose transporters responsible for the import of glucose in rats, GLUT2 was shown to be the predominant glucose transporter in the liver [20]. Glucokinase (GK) then converts glucose into glucose-6-phosphate (Glc-6-P) [21]. Glc-6-P can fuel distinct biochemical pathways: the glycogen biosynthetic pathway, the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway (OPPP), and the glycolysis (Fig. 2). The liver-type pyruvate kinase (L-PK) gene encodes a key glycolytic enzyme induced in vivo in hepatocytes during the fasting-to-fed transition [22]. Once transported into the mitochondria, the end-product of glycolysis, pyruvate, is oxidized to provide acetyl-CoA that feeds the TCA cycle. Mitochondrial citrate is exported toward the cytosol and converted into acetyl-CoA by ATP-citrate lyase (ACL), thus providing precursors for de novo fatty acid synthesis. The NADPH required for fatty acid synthesis is provided by the OPPP and malic enzyme (ME). The two dehydrogenases in the OPPP generate two moles of NADPH during the conversion of Glc-6-P to ribulose-5-phosphate (Ru-5-P); Ru-5-P is further converted to ribose-5-phosphate and intermediates of the glycolytic pathway in the non-oxidative phase of the OPPP. Alternatively, ME can participate in both the pyruvate/malate and pyruvate/citrate shuttles, thus transferring reducing equivalents from NADH to NADPH in the process known as pyruvate cycling [23]. TAG assembly ultimately requires acyl-CoAs and glycerol backbones provided by cytosolic glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH). The microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTTP) ultimately transfers lipids onto the apoB polypeptide in the ER to form VLDL (Very Low-Density Lipoprotein) [24].

Schemes of carbon metabolism leading to triacylglycerol synthesis in hepatocytes of mice and in maturing embryos of Arabidopsis. The arrow thicknesses are proportional to net fluxes of carbon. Black stars indicate metabolites that are provided to the oil biosynthetic cells by the vascular system (hepatocytes) or by phloem elements (embryo cells of oilseeds). Dashed arrows represent abbreviated metabolic pathways. AcCoA, acetyl-coenzyme A; ACP, acyl carrier protein; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; DAG, diacylglycerol; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone-3-phosphate; FA, fatty acid; Fru, fructose; Fru-1,6-P, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; Fru-6-P, fructose-6-phosphate; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; GK, glucokinase; Glc, glucose; Glc-1-P, glucose-1-phosphate; Glc-6-P, glucose-6-phosphate; INV, invertase; KG, alpha-ketoglutarate; LPC, lysophosphatidylcholine; OAA, oxaloacetate; OPPP, oxidative pentose phosphate pathway; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PDAT, phospholipids:diacylglycerol acyltransferase; PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvate; 6-PG, 6-phosphogluconate; 2-PGA, 2-phosphoglycerate; 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; 6-PGL, 6-phosphogluconolactone; PGlyM, phosphoglycerate/bisphosphoglycerate mutase; PKp, plastidial pyruvate kinase; PRK, phosphoribulokinase; Ru-1,5-P, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate; Ru-5-P, ribulose-5-phosphate; RuBisCO, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; SUS, sucrose synthase; TAG, triacylglycerol; UDP-Glc, uridine diphosphoglucose.

In oilseeds, the main organic compounds provided to the maturing embryo consist of sucrose and amino acids [25,26]. Incoming sucrose is cleaved by invertases (INV) or sucrose synthases (SUS; Fig. 2). The hexose phosphates released can fuel distinct biochemical pathways: the starch biosynthetic pathway, the OPPP, and the glycolysis. During the maturation phase, hexose phosphates are thought to be massively metabolized through the glycolytic pathway before utilization for de novo fatty acid synthesis in the plastid [27]. Glycolysis in plants can occur both in the cytosol and the plastid, both compartments being connected through plastid membrane transporters. In maturing embryos of rapeseed, enzymes of the full glycolytic sequence are detected in both compartments [28]. Yet, complementary studies suggest that glucose is predominantly broken down in the cytosol to phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), which is then imported into the plastid where it is further metabolized by the plastidial pyruvate kinase (PKp) and pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) [29–32]. During the formation of acetyl-CoA by the PDC, one third of the carbon of precursors for fatty acids is released as CO2, and without refixation, a substantial fraction of the carbon entering oilseeds would be lost [20]. In green maturing embryos, ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RuBisCO) is able to refix this CO2, thus increasing the efficiency of carbon use [33]. This metabolic route involves the conversion of hexose phosphates to ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate (Ru-1,5-P) by the non-oxidative reactions of the OPPP together with phosphoribulokinase (PRK), and the subsequent conversion of Ru-1,5-P and CO2 to 3-phosphoglycerate (3-PGA) by RuBisCO [33]. De novo fatty acid synthesis in the plastid (prokaryotic pathway) generates C16:0, C16:1 and C18:1 species, which are then exported to the ER for modification (elongation, desaturation) in the so-called eukaryotic pathway. In maturing embryos of rapeseed, mitochondrial metabolism is largely “unconventional”: flux around the TCA cycle is absent and mitochondrial substrate oxidation contributes little to ATP production [26]. All the citrate formed in the mitochondria is exported toward the cytosol and used for the production of precursors required to elongate very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA; C ⩾ 20). Most of the mitochondrial metabolic flux is thus devoted to cytosolic fatty acid elongation. Ultimately, TAG assembly can be considered as proceeding by two distinct routes [12]. One of these, the Kennedy pathway, involves a network of linear reactions and relies on the sequential acylation (by glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase, and diacylglycerol acyltransferase) of a glycerol-3-phosphate (Gly-3-P) backbone provided by GPDH. The second route relies on acyl-exchange between lipids and involves a phospholipids:diacylglycerol acyltransferase (PDAT). The study of carbon fluxes in developing embryos of rapeseed cultured in vitro has established that the reducing power produced by the OPPP was accounting for at most 44% of the NADPH and 22% of total reductant needed for fatty acid production [22]. The role of the OPPP in NADPH production being limited and the respiratory TCA flux being absent in embryonic tissues, an alternative source of reductant and ATP is used to face the high energetic demand of maturing embryos. Provided that enough light is available, photosynthesis takes place within plastids of green seeds that supplies NADPH and ATP for energetically expensive fatty acid syntheses [33]. Interestingly, increasing light intensity during seed maturation can even improve significantly the efficiency of oil synthesis in developing embryos [34].

3 Regulatory mechanisms controlling the oil biosynthetic machinery

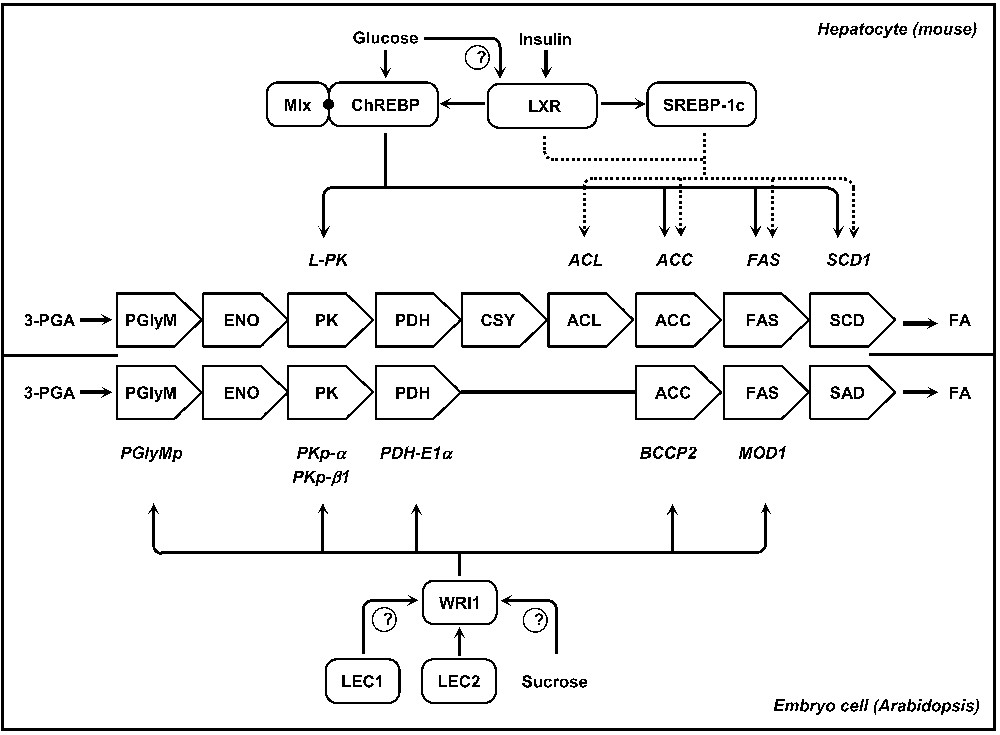

De novo lipogenesis in hepatocytes is nutritionally regulated and both glucose and insulin are elicited in response to dietary carbohydrates to synergistically induce glycolytic and lipogenic gene expression [6] (Fig. 3). The transcriptional effect of insulin is mediated by sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), a transcription factor of the basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper (bHLH/LZ) transcription factor family. Transcription of SREBP-1c is induced in vitro by insulin and inhibited by glucagon [35]. SREBP-1c induces lipogenic genes like ATP-CITRATE LYASE (ACL), ACETYL-COENZYME A CARBOXYLASE (ACC), FATTY ACID SYNTHASE (FAS), and STEAROYL-COA DESATURASE (SCD) by its capacity to bind to a sterol regulatory element (SRE) present in the promoters of its target genes [36,37]. Yet, SREBP-1c activity alone does not appear to fully account for the stimulation of glycolytic and lipogenic gene expression in response to carbohydrate diet and a distinct signaling pathway is also critical for this transcriptional activation. Glucose- or carbohydrate-response elements (ChoREs) have been identified in the promoters of most lipogenic genes. These ChoREs mediate the transcriptional response of glucose and consist of two E box-like sequences (CACGTG) separated by five base pairs. Each of these E boxes is recognized by a heterodimer of the bHLH/LZ transcription factors ChREBP (carbohydrate responsive element-binding protein) and Mlx (Max-like protein X) that bind cooperatively to the ChoRE [38]. Targets of the ChREBP/Mlx complex include L-PK, ACC, FAS, and SCD genes. Mlx is thought to target ChREBP to appropriate gene sequences by supporting its recognition of the ChoRE [39]. Of the two partners of the complex, ChREBP is most likely the direct target of glucose signaling. ChREBP is firstly regulated by glucose at the transcriptional level [40]. Then, glucose activates ChREBP by controlling its entry from the cytosol into the nucleus [41]. Interestingly, liver X receptors (LXRs) have also been shown to act as important regulators of the lipogenic pathway. LXRs are ligand-activated transcription factors that belong to the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily [42]. They are central for the insulin-mediated induction of SREBP-1c [43,44], and in addition to the transcriptional activation of SREBP-1c, LXRs are also able to trigger directly the transcription of lipogenic genes such as ACC, FAS or SCD-1. Known ligands of LXRs are oxysterols but glucose was also recently suggested to bind and activate LXRs leading to the activation of their target genes, including ChREBP [45]. These data have established LXRs as master lipogenic transcription factors, as they directly regulate both SREBP-1c and ChREBP to enhance hepatic fatty acid synthesis [46]. However, the relative contribution of LXR to ChREBP regulation and glucose signaling remains a matter of debate [47].

Models for the transcriptional regulation of fatty acid synthesis in hepatocytes of mice or in maturing embryos of Arabidopsis. In the central part of the figure, metabolic pathways converting 3-PGA into fatty acids are presented for each of the biological systems considered. The enzymatic activities involved are reported, side by side, in open arrows. Corresponding genes are indicated in italics and the regulatory networks controlling the transcriptional activation of these genes are schematized. ACC, acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ACL, ATP-citrate lyase; CSY, citrate synthase; ENO, enolase; FA, fatty acid; FAS, fatty acid synthase; PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglycerate; PglyM, phosphoglycerate mutase; PK, pyruvate kinase; SAD; stearoyl-ACP desaturase; SCD, stearoyl-CoA desaturase.

Among the regulators known to control seed maturation in Arabidopsis, LEC2 is of particular interest since its induction correlates with the onset of oil accumulation in the seed. What is more, ectopic expression of LEC2 can confer embryonic characteristics to transgenic seedlings, triggering TAG accumulation in developing leaves normally deprived of TAGs [18,48]. Recent reports have described a set of genes directly controlled by LEC2, providing original insights into the transcriptional control of embryo maturation [49]. Although several genes encoding lipid-body associated proteins have been identified, none of the genes involved in C primary metabolism or in fatty acid biosynthesis appear to be directly controlled by the master regulator. These observations have led to hypothesize that fatty acid synthesis may be indirectly regulated via secondary transcription factors able to trigger their own transcription program. WRINKLED1 (WRI1) is a target of LEC2 that encodes a transcription factor of the plant-specific APETALA2-ethylene responsive element-binding protein (AP2-EREBP) family [50,51]. In wri1 seeds, primary metabolism is compromised, rendering maturing embryos unable to efficiently convert sucrose into TAGs [52,53]. Putative targets of WRI1 include several genes encoding enzymes of late glycolysis and the plastidial fatty acid biosynthetic machinery: a phosphoglycerate mutase (At1g22170), pyruvate kinases PKp-α (At3g22960) and PKp-ß1 (At5g52920), pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) E1α subunit (At1g01090), acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase (ACCase) biotin carboxyl carrier protein (BCCP2) subunit (At5g15530), and the enoyl-ACP reductase MOD1 (At2g05990) [30,51]. WRI1 thus specifies the regulatory action of LEC2 toward the metabolic network involved in the production of fatty acids. These results exemplify how metabolic and developmental processes affecting the maturing embryo can be coordinated at the molecular level. Further analyses are now required to fully elucidate the regulatory network controlling fatty acid production. Considering the up-regulation of WRI1 in turnip mutants that ectopically express LEC1 but not LEC2, it could be hypothesized that LEC1 participates to the induction of WRI1 in maturing seeds [54]. Finally, several studies have suggested that WRI1 might constitute a mechanistic component of the sugar response in seedlings or leaves [55,56]. It would be interesting to test whether a similar regulation occurs in maturing embryos, and whether LEC1 participates in the mediation of this sucrose response.

4 Concluding remarks

TAGs act as an energy reserve both in the liver of mice, where lipogenesis is induced by a high carbohydrate diet, and in developing embryos of Arabidopsis, where a developmental program triggers oil accumulation at the onset of seed maturation. If similar sequences of enzymatic activities have been conserved that participate in lipogenesis in both systems, the metabolic network responsible for oil synthesis in embryos of Arabidopsis is more complex. It is composed of several intricate, partially redundant metabolic pathways, and relies on various sources of NADPH. In both systems, induction of lipogenesis relies on the transcriptional activation of a set of genes encoding enzymes of late glycolysis and fatty acid biosynthetic machinery. Yet, distinct transcriptional regulatory systems have evolved that trigger lipogenesis in response to specific signals (high carbohydrate diet in mice or seed maturation program in Arabidopsis). In both systems, the induction of lipogenic genes is controlled by transcription factors, the transcription of which is triggered (at least partially) by so-called “master regulators”. The regulatory network thus defined integrates hormonal and sugar signaling, but more studies are now required to fully elucidate the molecular bases of such crosstalk. Interestingly, some orthologs of the genes regulating lipogenesis in mammalians have been found to exhibit similar functions in invertebrates like Caenorhabditis elegans [57], whereas the fission yeast ortholog of SREBP regulates anaerobic gene expression [58]. At that stage, it would be interesting to further investigate the evolution of these genetic cascades in various organisms in relation with the metabolic networks they control.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Martine Miquel for critical reading of the manuscript. Our work on seed maturation is supported by grants from the Génoplante GOP-Q3, TRIL-033 (P-009 Arabido-seed), and Plant-TFcode programs.