1 Introduction

Four decennia after visiting Tierra del Fuego, Darwin wonders at end of The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) what his origins would have been if he could have made a choice concerning his biological descent. Musing in a way that is more philosophical and existential than scientific, Darwin writes that he would have preferred baboons to Fuegians as his ancestors:

“For my own part, I would as soon be descended (…) from that old baboon, who, descending from the mountains, carried away in triumph his young comrade from a crowd of astonished dogs – as from a savage who delights to torture his enemies, offers up bloody sacrifices, practices infanticide without remorse, treats his wives like slaves, knows no decency, and is haunted by the grossest superstitions.” [1] (emphasis added).

It is, of course, a provocative remark that comes from a man who has already shocked a conservative society by demonstrating in 1858 that humans are animals that evolve. However, beyond this provocation lies a genuine identification with the brave baboon who was hunted by the former German ornithologist and animal collector, Alfred Brehm. It also shows a great disgust for the behaviour and habits of Fuegians. So, in this article, almost a century and a half later, we want to contrast Darwin's observations and beliefs with today's knowledge about monkeys and apes – especially baboons –, and about the now extinct Fuegian cultures. We would also like to speculate on the reasons for Darwin's choice:

- • What do we really know about the Fuegians (actually four different cultures – with certainly many “tribes” –, which have all disappeared)?

- • What was Brehm's original account of the brave baboon that saves an infant?

- • Finally, what are the biological and moral meanings of Darwin's choice?

2 The mature Darwin discussing with the young one on humans and monkeys

Almost 150 years after the publication of On the Descent of Man, both primatology and anthropology have made great progress, acquiring a broad knowledge concerning the behavior of hundreds of non-human primate species and of different human cultures.

We know that the Beagle voyage was the most important experience of Darwin's life. It impacted not only his scientific views, but also his existential and philosophical tendencies.

What was the knowledge Europeans had from two living group of organisms from which they did not have precise facts: apes – since Europe did not possess endemic populations of non-human primates – and “savages”?

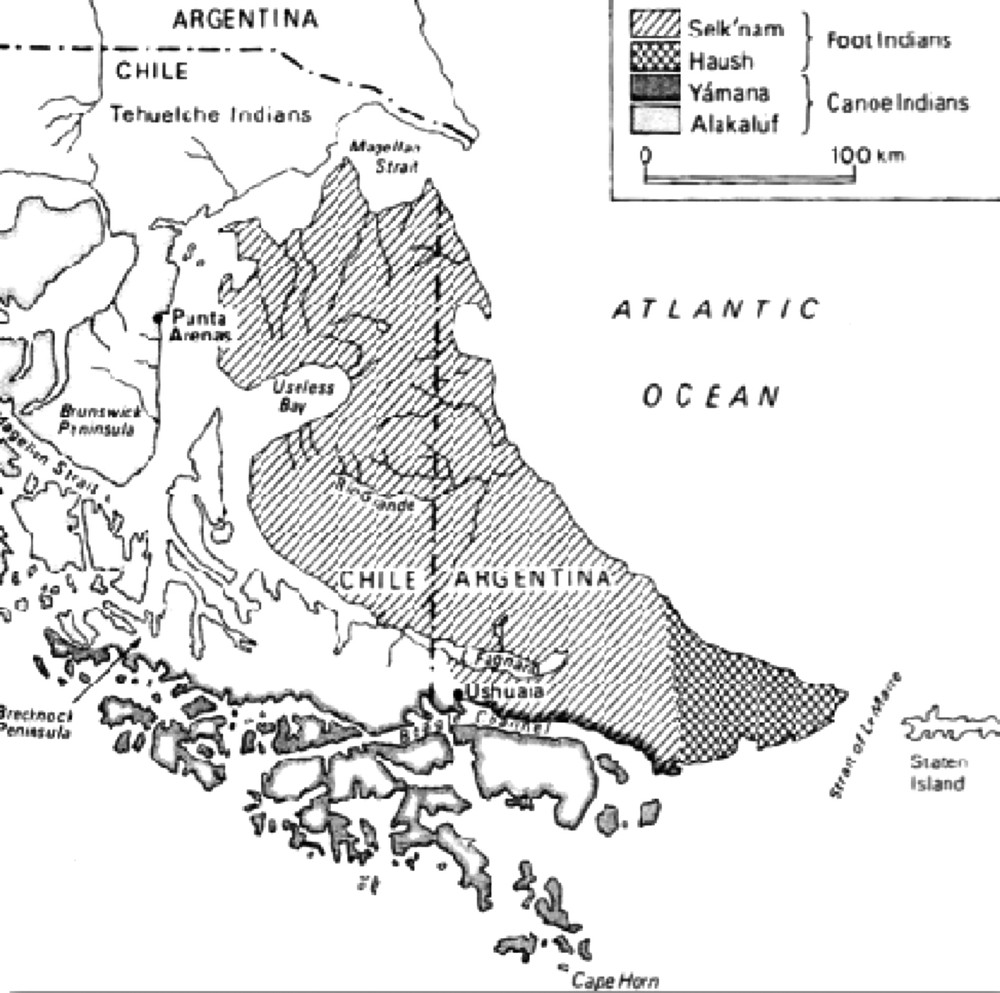

We think, in the first place, that Darwin's passage, quoted above, reflects a synthesis of his thoughts concerning the place of humans in the living world, and concerning their moral progress. This is clearly a desire, not a fact. Darwin never says we descended from extant primates. Rather, he says that we probably descended from similar ancestral forms. He compares two living groups. One, the Papio hamadryas baboon, is considered more instinctive in its behaviour. The other is a less instructed human culture than his, one that was comprised of at least four linguistically different hunter-gatherer societies: Alakalufs, Yaghans, Selk-nam and Haush [2].

With one of the subjects, the “savages”, Darwin had had a personal experience in the 1830s, thanks to the Beagle's second visit to Tierra del Fuego under Captain Fitzroy's command. Fitzroy had previously surveyed the same area between 1828 to 1830 and captured four Fuegians as punishment for stealing a whaleboat from him. The captives included members of at least two different societies, including “Fuegia Basket”, a nine-year-old child. Fitzroy wanted to “civilize” and Christianize them, and to turn them into agriculturists. Only three survived. Their reintroduction as civilized Christians into their societies was terrible and, unfortunately, Englishmen learned nothing from this terrible mistake [3], since they continued to try the same strategy for years.

However, for the purpose of this study, we want to highlight the fact that Darwin had had the extraordinary opportunity to interact with captive and free hunter-gatherers of one of the most astonishing groups of societies. For Darwin, the Fuegians represented important study subjects for two main reasons: they could have been the most primitive living human beings on Earth (we know now that this is not true); and they certainly managed to survive in one of the most inhospitable places of the world. He says on first seeing the Fuegians:

“The astonishment which I felt on first seeing a party of Fuegians on a wild and broken shore will never be forgotten by me, for the reflection at once rushed into my mind—such were our ancestors.”[1]

We may agree with Darwin on his remarks on the harsh ecological conditions in which these people lived, and also notice that he had the extraordinary opportunity to interact with a now extinct group of humans, something that few naturalists before him had. Darwin had seen a group of Haush, but he did not know they belonged to a different culture than that of “Jeremy Button”, one of the three Fuegians brought back from England, who was Yaghan. Button hated the Haush (and the Selk-nam, whom the Yaghans called Onas) and wanted the Beagle to shoot at them. Neither Darwin, nor Fitzroy, nor their colleagues understood much about the Fuegian cultures. We shall try, indeed, to show that Darwin was a poor anthropologist, probably as bad as all of his contemporary scholars were.

Concerning ape and monkey behavior, on the contrary, Darwin did not have the same existential experience as in Tierra del Fuego. His acquaintance with non-human primates was certainly very limited. It was restricted to captive animals in zoos – where he did remark the keen attention of an orangutan towards humans –, and perhaps also to pet animals seen in Brazil, since the South American arboreal monkeys are all difficult to observe in the wild. He might have had had the generalized European idea of monkeys being funny but useless beings [4], since he mentions observing the Fuegians when they seemingly were not engaged in directed activity “as monkeys” (this observation would have been made when the Fuegians were acting calmly, because otherwise the Englishmen were afraid of them). But many years after the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin read the English translation of Alfred Brehm's (1829–1884), famous book about wild animals, Thierleben [5]. Brehm was a German ornithologist, a collector of African species and, like Darwin, a hunter. In Thierleben, Darwin found the account of a brave baboon that risked his life in order to save an infant from a pack of dogs.

Concerning South American human cultures, we must remember that Tehuelche Patagons, probably of the Aónikenk culture, were first seen and described by Pigafetta (Magellan's around-the-world expedition chronicler), as gentle giants (capac). They were baptized by the Portuguese captain as “Patagones1” since their large guanaco winter shoes left a large footpath. The Tehuelche and Selk-nam (Onas) were indeed tall (1.80 m or more: see Figs. 1 and 2), as a 1882 French Cape Horn Expedition (EFCH) [6] later established; they were much taller than 16th Century Spaniards, but they were not strictly giants. They were also much taller and had stronger legs that the “boat” Fuegians, the Yaghans, as one can easily see from the famous drawing of a Yaghan and also by observing some of the EFCH photographs (cf. infra). Members of Magellan's expedition did not see any of the Fuegians, but saw their bonfires, which we know today to have been the Fuegians’ indication that something big, such as a stranded whale or an unknown vessel, was arriving. Because of the bonfires, Magellan baptized the area Tierra del Fuego.

A couple of Yaghans. Notice how slim their legs are (they lived most of the time on a boat). They are less tall than the Selk-nam, who had very strong legs. Photo 1882 (ESCH).

A couple of Selk’nams. Notice their long furs. Photo 1882 (ESCH).

We will not mention the subsequent European visits, some of which precipitated terrible events that, at the end of the xixth and beginning of the xxth Centuries, would bring the demise of those extraordinary cultures.

Concerning the incident with the “brave baboon”, we wonder:

- • Why had only one animal had come down to help the infant (they usually mob their enemies)?

- • What kind of dogs was accompanying Brehm and his hunting party?

Darwin seems to project onto the Fuegians the Europeans’ idea of “the savage,” which functioned to help provide moral justification for acts committed during four centuries of conquering the world. If we compare Fuegians to baboons as Darwin does at the end of The Descent, what do we find?

The Fuegians did not “delight in torturing their enemies”, but certainly there was not peace between the three southeastern groups, Selk-nam, Haush and Yaghan (see Fig. 3). The tall Selk-nam, probably of Tehuelche origin, were not the first to come to the Big Island on Tierra del Fuego. The Haush were, but the Selk-nam chased them to marshy areas further to the south, where they had to adapt in order to survive. The Selk-nam remained “land and guanaco people,” since they relied on the guanaco for most of their needs. The Haush remained on land, but they had to find food on the shores. They collected shells and used sea lions for most of their needs, but they did not have boats. Finally, the Yaghan were boat people, like the Alakalufs in the West. They spend most of their time on their canoes, although they built huts that they moved frequently within a certain territory, just as the Selk-nam and Haush did.

Probable distribution of the four Fuegian cultures in 1832–33 [2].

Answering another of Darwin's queries, neither the Fuegians nor the baboons tortured their enemies or offered blood sacrifices. The Fuegians were hunter-gatherer societies; they did not have human sacrifices.

Concerning infanticide, the baboons do perform it. Quite probably the Fuegians did too, because all human cultures do so, whatever their laws might be. We do not know whether the Fuegians felt remorse for acts of infanticide. And we cannot attribute remorse to baboons.

Did the Fuegians treat their wives as slaves? Hunter-gatherer societies are less “male chauvinist” than agricultural ones. In the case of Fuegians, the English sailors and Darwin – not precisely feminists – were astonished to see how much Yaghan women had to do in their daily routine. They collected shells on the shore or dived naked, fished, maintained the fires and cooked (they were able to start fires under the rain), while the men did not seem to do anything in the meantime.

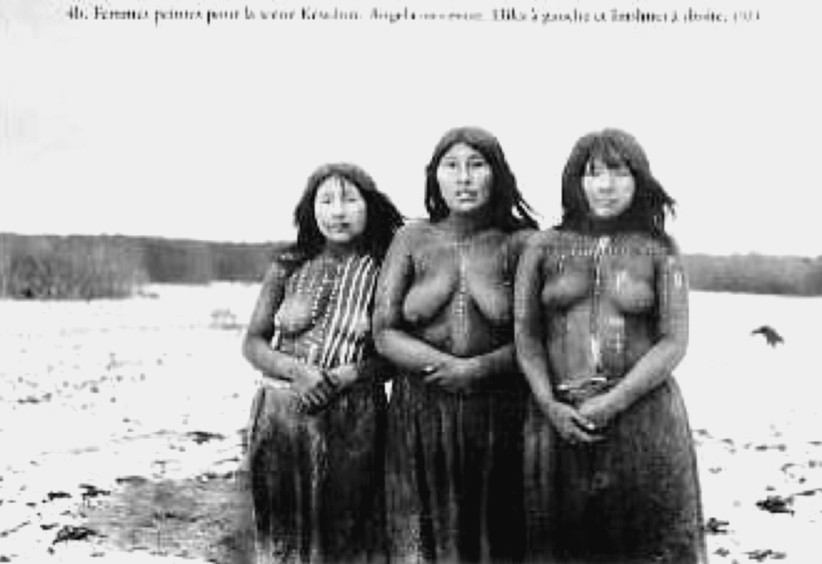

The Selk-nam, who used a much larger guanaco skin, went naked while doing many activities, such as hunting. Years later, it was shown that they could sleep a whole night with parts of their legs exposed to weather under 0 °C, something that not even Inuit do. They certainly had a physical (not only a cultural) adaptation to their ecosystem, but all information about it is lost for science. So, when Darwin says they “know no decency”, he probably refers to the way they so easily went naked (Figs. 4 and 5). But they had, as all human cultures possess, decency rules. The most obvious of these was to always wear a cache-sexe (Amazonian cultures, which go totally naked and use no cache-sexe, have some rules of how to sit “decently”, for instance). Among baboons and among most of other mammals, there are positions an animal can or cannot adopt, depending on who is in his vicinity. Yet we cannot call this “decent behavior”.

A young and beautiful Yaghan woman, ca. 1882 (ESCH). They went naked very often (specially when swimming), something that shocked Darwin and his English companions.

Selk’nam ladies: Ángela Loja, middle, painted according to her Constellation, the North or the whale, Ca. 1920 (From Anne Chapman) [3].

Finally, our naturalist affirms that the Fuegians were “haunted by the grossest superstitions”. But then, all human societies – including that of Darwin and his companions on the Beagle – have religious and mythical beliefs that are, after all, superstitions. So there is no difference in that either. And, since there is not anything closer to superstitions than instinctive behavior, we could say that baboons are indeed superstitious.

3 Physical aspect, behaviour and technology of Fuegians

In The Descent Darwin writes:

“These men were absolutely naked and bedaubed with paint, their long hair was tangled, their mouths frothed with excitement, and their expression was wild, startled, and distrustful. They hardly possessed any arts, and lived on what they could catch like wild animals; they had no government, and were merciless to everyone outside of their own small tribe. He who has seen a savage in his native land will not feel much shame, if forced to acknowledge that the blood of some more humble creature flows in his veins.” [1,p. 404]. (emphasis added).

But many years before, in his Beagle Diary, he gives us a wonderful description of a Yaghan, while Conrad Martens, the official painter, produces a magnificently precise watercolour of a Yaghan, his boat and hut (Fig. 6). Darwin, adding a dog to it, used this portrait afterwards; he had noticed how Fuegians greatly appreciated the domestic dogs that came to South America with the Spaniards.

“The skin is dirty copper colour (…) the only garment was a large guanaco skin, with the hair outside. — This was merely thrown over their shoulders, one arm & leg being bare; for any exercise they must be absolutely naked. — Their very attitudes were abject, & the expression distrustful, surprised & startled: — Having given them some red cloth, which they immediately placed round their necks, we became good friends” [8: 266].[8]

Unknown Yaghan painted by Conrad Martens in 1833.

Notice the furs this man wears (Fig. 6). Yaghans used the coats of both guanaco and fox (a different, larger species than those native to Europe), so this man's furs might have come from either animal. Unlike the Patagons, the Yaghans wore furs with the hair on the outside, because they dried better that way. And as Darwin noted, they did not use anything to attach the furs to their body.

In this wonderful painting, the watercolorist – who, unfortunately for Darwin did not accompany him to the Galapagos – shows in great detail many aspects of the material culture of the Yaghans, which did not change in almost a century. This man – quite similar in aspect to the couple captured in a 1882 photograph (Fig. 1) – is wearing a lace made from whale tendons to hold his hair; he has a beautiful necklace; he is also wearing the red piece of cloth the Englishmen gave to a group of Fuegians; he is smoking a pipe; he wears leather arm and leg bracelets; he uses the guanaco (or fox) skin, with the hair on the outside. It reaches only down to his waist, which is how the Yaghans wear furs. Selk-nam, or land Fuegians, wear a long skin that reaches down to their legs [7] (Fig. 2). In the background of the watercolor, we can see the man's boat, near a bush with white flowers (it was summer). Boats of this type were extraordinary vessels. Their hulls were made from special bark freshly cut during a certain time of the year, and their frames were made with exceptionally good wood. We know the craft were seaworthy because Chapman has shown that they were able to reach Staten Island and brave the terrible Le Maire strait. These boats carried a furnace, together with oars and a large quantity of baskets adapted for each type of fish. We can see the picture of a similar vessel taken in 1882 (Fig. 7).

A Yaghan boat in 1882 (ESCH). Notice the different basquets, harpoons, bows and rows it has. They also carried a furnace in the middle of the boat [6].

4 Brehm's brave baboon

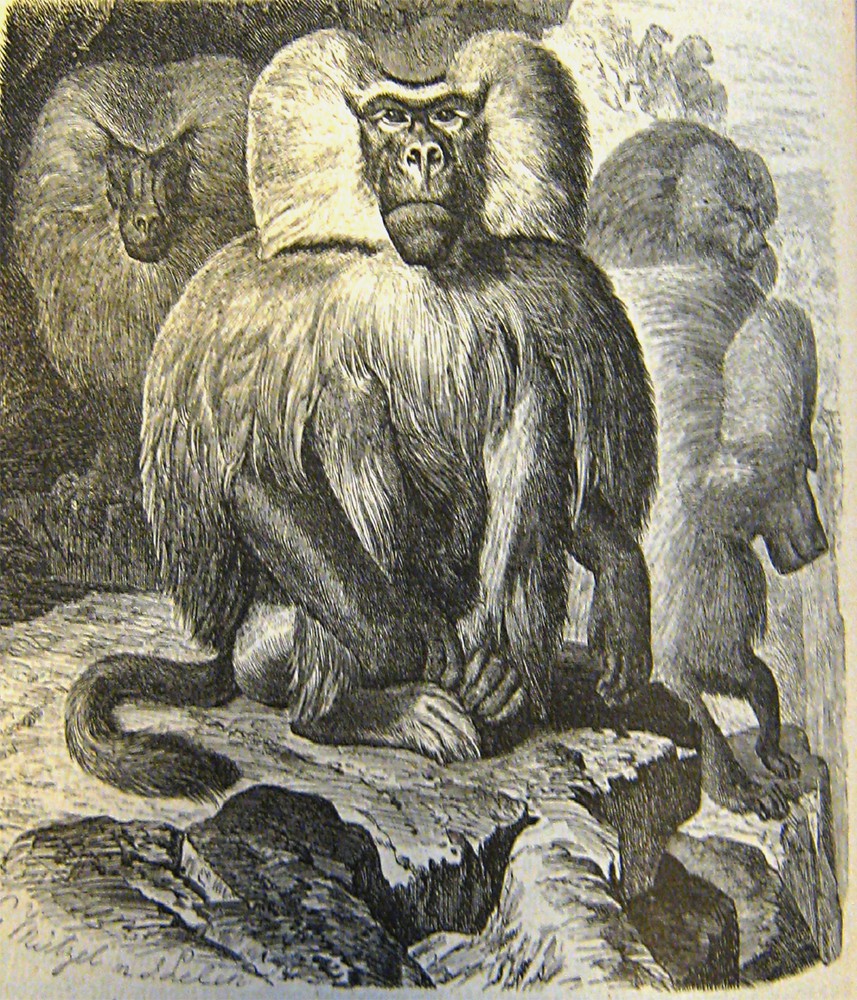

The brave baboon who saved an infant from the dogs (and the hunters) was a large male (Fig. 8). He was an old male who was probably, but not necessarily, the alpha male of the group. We can speculate that the infant was either his biological or adopted son. In either case, it was his “official” infant. This is because like male humans, male baboons cannot know for sure whether they are an infant's parent, and because they occasionally adopt other baboons’ infants, sometimes by force.

An alpha hamadryas male, similar to Darwin's “brave baboon” (Brehm's Thierleben, 1876).

Why compare savages with baboons and not with apes, such chimpanzees, which were described in 1699 as the closest to humans, or the recently (1847) discovered Gorillas? [9].

Hamadryas is the absurd name of a nymph that was given to these baboons by Linnaeus. Notice the leopard in the grass, the worst enemy in Ethiopia (in the rest of Africa it is the lion more than the leopard), not to mention humans.

What do we know today of hamadryas baboon group structure and behaviour? They possess an apparently loose structure that in fact is quite homogeneous, once their four level structure is put into light. They are subdivided in:

- • Harems, which are unimale groups. They have a single dominant male, and 2 to 11 females (Figs. 8 and 9);

- • Clans, comprised of groups of harems lead by males that are genetically related;

- • Bands, or groups of clans that forage together during the day (20 to 70 animals). The genetic closeness still exists in the bands, but on a lower degree than in clans;

- • Troops, which are groups of bands that sleep together on cliffs and which constitute groups of 700 individuals. [10]

A hamadryas’ harem on a cliff, according to Brehm. Notice the leopard on the grass, baboons’ worst enemy on the cliffs (while in the savanna, it is the lion) (1876).

The existence of such substructures had produced a lot of confusion at the beginning of the census on baboon studies – especially on the savannah baboon (Fig. 10) subspecies census –, and it was thought that hamadryas had a different structure. Actually, since they are cliff-sleeping creatures, they are observed more often in small bands, even clans, but not as frequently as other Papio subspecies in large groups.

Olive baboon (J. Martinez 2006 photo, Uganda).

With this knowledge in hand, we may conclude that Brehm and his party of hunters and dogs confronted a lonely clan headed by a single large male. Was he the father of the infant? We know that male baboons adopt infants whose parents have died and even, sometimes, kidnap infants from other animals. They also possess a structure of consort males, where a less dominant male acts as a kind of “uncle” (in anthropomorphic terms) of the dominant male's offspring. In the case that interests us, and impressed Darwin so much, we may conclude that the male in question was either the father or a consort of the alpha male of the clan, since according to the group size, it was indeed a clan. Because the animals were often hunted with dogs, they could associate the noise of firearms and the presence of Canis with harm. However, these animals do not always risk their lives to save an infant, since there is more survival fitness in saving reproductive adults than offspring. Furthermore, for this analysis, we consider the race of the hunting dogs: they were greyhounds. This kind of dog is one of the best for swift and long prey chases, but they are not good at fighting, unlike bulldogs, for instance. In a certain way, the large baboon may have rapidly evaluated all these factors and “decided” to try to save the infant. The dogs did not dare attack the 30 kg monkey who was armed with impressive canines, and the hunters, astonished by such bravery, did not shoot. Yet Brehm says they were close enough to hit the animal and, elsewhere in the same book, he declares that baboons deserve to be hunted since “they do not think”. This is contradictory thinking by a man who affirms to have admired the behaviour of this brave Cynocephalus. Darwin certainly did not isolate the human mind from that of animals in a Cartesian manner, as the Germans did.

5 Conclusion

Darwin was a good reader of animal behavior, as well as a fine ethologist, and he could decipher in the hamadryas baboon an altruistic intention (albeit one which was also egotistical, since the male was protecting his infant). This was something Brehm, the hunter, was unable to see.

Being a good interpreter of behavior, and believing in a total continuity between animals and humans, he opened the way for Koehler, the first experimental psychologist of apes (although the Prussian never mentions Darwin), to propose experimentally that chimpanzees possessed insight, reflection or reason.

For these reasons, Darwin was an evolutionary moral philosopher, and forerunner of the contemporary discussions about the natural basis of moral feelings in which we engage more than one century after his death.

He deserves the homage we are paying to him almost 200 years after the Beagle's second voyage.

1 The origin of the name is uncertain. The Tehuelches left huge marks on the ground when using their guanaco winter shoes. Patones, meaning “huge feet”. Magellan was also reading one of the chivalry books that inspired Cervantes, Primaleón.