1 Introduction

As discussed in a recent publication [1], scorpion diversity is particularly great in deserts and arid formations [2]. The scorpion fauna of North Africa, particularly that specifically adapted to the Sahara desert, has been the subject of intensive study. This was synthesised in the monographic work of Vachon [3]. Nevertheless, more detailed inventory work and the revision of classical groups have revealed an increasing number of new species and even new genera. A synthesis is available in Lourenço and Duhem [1]. From this, it is apparent that knowledge of this fauna is still far from complete. Many other species and probably genera too await discovery. A similar assumption can be made about the fauna of the peri-Saharian regions. These regions, located on the periphery of the Sahara ‘central compartment’ (see below) [3], are particularly diverse in elements that, in the past, occupied most of the present Sahara, whenever the general climate was more mesic. With the development of aridity, the scorpion lineages, incapable of readaptation, experienced an extensive regression in their geographical distribution. Consequently, these lineages are now represented by isolated relictual elements.

Here, we describe one new remarkable addition to the family Buthidae, C.L. Koch, 1837. A new genus and species, collected in the region of the Great Rift Valley in the North of Kenya. This new genus appears more of a ‘puzzle’ since it possesses characters seen in several buthid genera, especially, Uroplectes, Peters, 1861; Uroplectoides, Lourenço, 1998; Lissothus, Vachon, 1948; Pseudolissothus, Lourenço, 2001; Sabinebuthus, Lourenço, 2001 and also Buthus, Leach, 1815 and Leiurus, Ehrenberg, 1828.

2 Material and methods

Illustrations and measurements were made with the aid of a Wild M5 stereo-microscope with a drawing tube (camera lucida) and an ocular micrometer. Measurements follow Stahnke [4] and are given in millimeter. Trichobothrial notations follow Vachon [5] while morphological terminology mostly follows Vachon [3] and Hjelle [6].

3 Taxonomic treatment

Family Buthidae, C.L. Koch, 1837

Genus Riftobuthus gen. n.

Diagnosis. Small scorpions, 22.19 mm in total length (including telson). Coloration globally yellowish to pale yellow. Carapace acarinated and smooth. Tergites smooth with one vestigial median carina. Dentate margins on fixed and movable fingers of pedipalp chela composed of nine to 10 linear rows of small granules, almost forming a single row; outer and inner accessory granules absent from both fingers; two very small granules located proximally to the terminal granule on the movable finger. Sternum sub-triangular. Pectinal tooth count 36-36; fulcra present but weakly marked; basal middle lamellae strongly dilated. Spiracles linear but very short. Chelicerae with one single basal denticle on the movable finger. Metasomal segment V with the anal arc composed of nine to 10 strongly reduced ventral teeth and two uniform lateral lobes. Telson; vesicle pear-shaped with a long aculeus; subaculear tooth absent. Tarsi with two series of moderately long setae. Trichobothrial pattern A-α (alpha), orthobothriotaxy. Trichobothrium d1 of femur displaced over the external face of the segment.

Derivatio nominis: after the Great Rift Valley region where the scorpion was found.

Type species Riftobuthus inexpectatus sp. n.

4 Affinities of the new genus

Riftobuthus gen. n. shows affinities with several other buthid genera, in particular with Lissothus, Pseudolissothus, Sabinebuthus, Uroplectes and Uroplectoides. Common features with the genera cited are carapace and tergites acarinated and smooth. The strongly dilated basal middle lamellae would indicate that Riftobuthus gen. n. is more closely related to Uroplectes and Uroplectoides, whereas the dentate margins on fixed and movable fingers of pedipalp chela composed of linear rows of granules, forming almost a single row, is rather similar to what is found in Sabinebuthus.

The new genus can, however, be distinguished by a unique combination of characters:

- • carapace and tergites acarinated and smooth;

- • pectines extremely long with an unusually large number of teeth (36-36), dilated basal middle lamellae and weakly marked fulcra;

- • the dentate margins of pedipalp chela fingers composed of linear rows of granules, forming almost a single row;

- • trichobothrial pattern A-α (alpha), orthobothriotaxy, with trichobothrium d1 of femur displaced over the external face of the segment;

- • chelicerae with one single basal denticle on the movable finger;

- • metasomal segment V with the anal arc composed of nine to 10 strongly reduced ventral teeth and two uniform lateral lobes;

- • telson's vesicle pear-shaped with a long aculeus and the subaculear tooth absent.

The two last characters isolate the new genus from all the five previously cited and rather associate it to other genera such as Buthus and Leiurus.

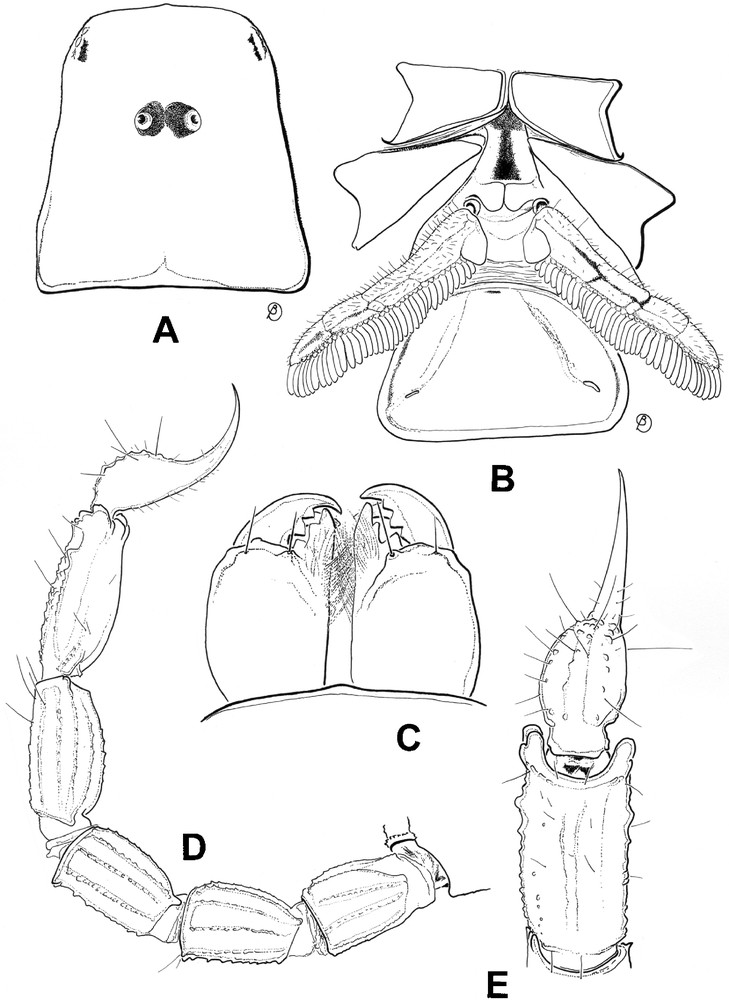

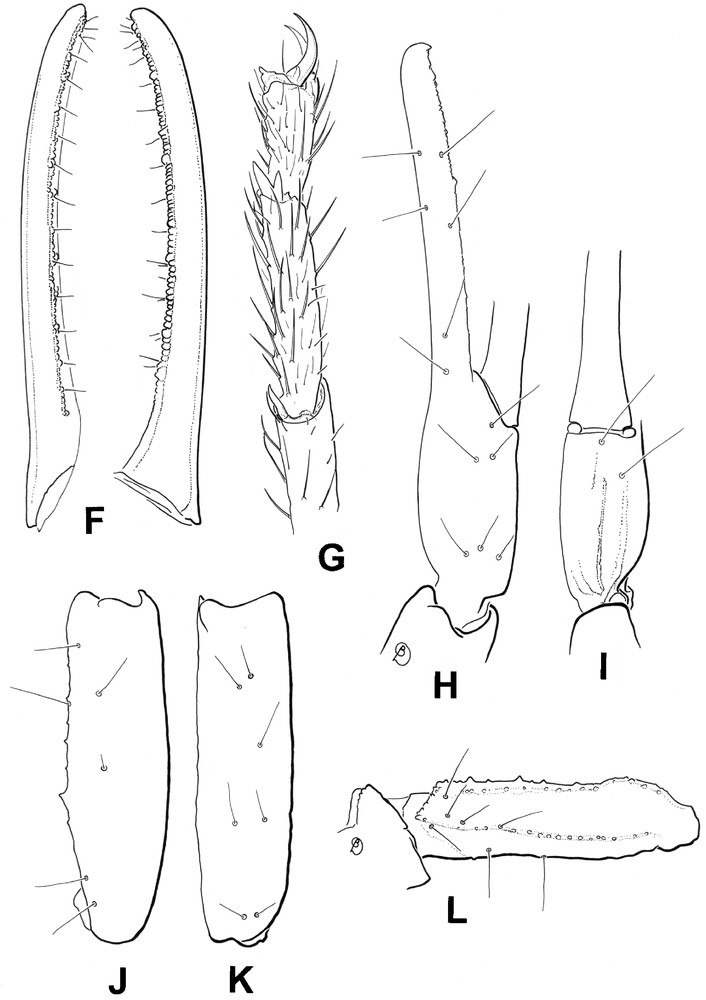

Riftobuthus inexpectatus sp. n. is presented in Figs. 1–3.

Riftobuthus inexpectatus sp. n., female holotype. A. Carapace. B. Ventral aspect showing coxapophysis, sternum, genital operculum, pectines and sternite III. C. Chelicerae, dorsal aspect. D. Metasoma and telson, lateral aspect. E. Metasomal segment V and telson, ventral aspect.

Riftobuthus inexpectatus sp. n., female holotype. F. Cutting edge of movable finger, showing rows of granules, dorsal and lateral aspects. G. Leg IV, showing setation, pedal and tibial spurs. H-L. Trichobothrial pattern. H-I. Chela, dorso-external and ventral aspects. J-K. Patella, dorsal and external aspects. L. Femur, dorsal aspect.

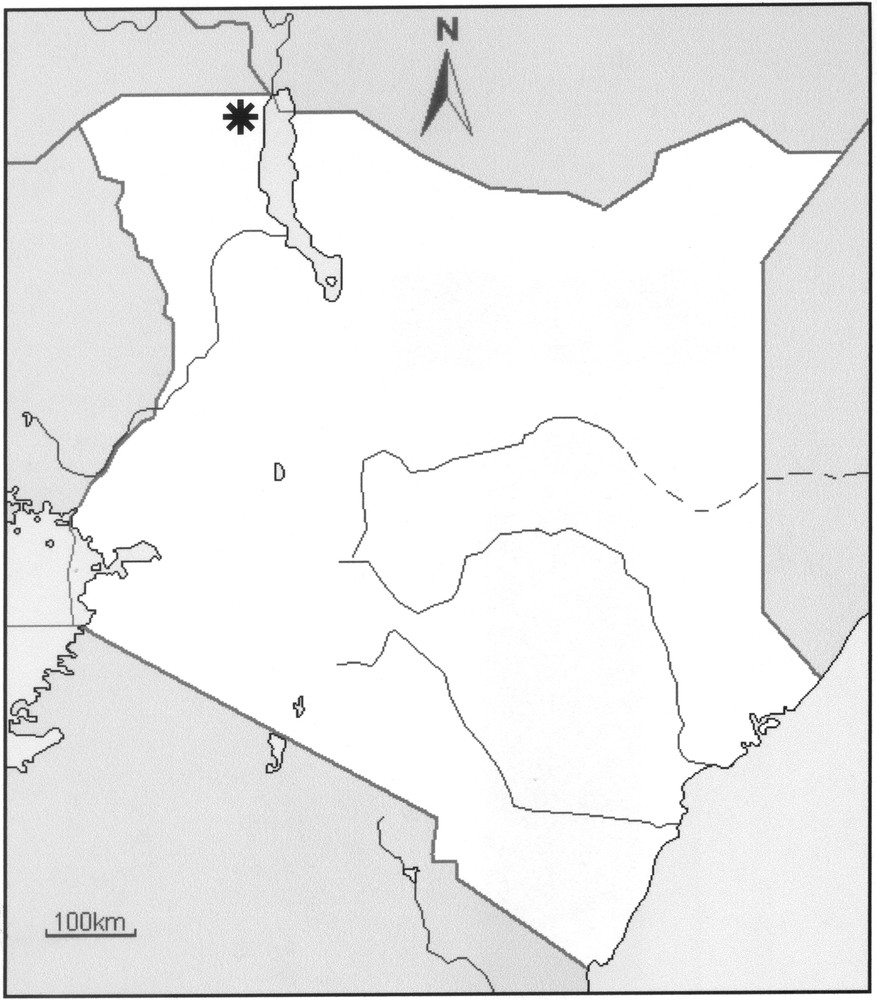

Map of Kenya showing the type locality of the new species (black asterisk).

Diagnosis: as for the new genus.

Type material: Kenya, region of Turkana, N. Lokitaung (near to the borders with Ethiopia and Sudan), 420 m alt., desert shrub and grass, under large rock (not a psammophilic element), XI/1970 (D. Rodhain), one female holotype. Deposited in the collection of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris.

Etymology: the specific name is a reference to the not expected finding of such a new taxa in Kenya.

Description based on the female holotype (measurements after the description).

Coloration: basically yellowish to pale yellow, with only median and lateral eyes surrounded by dark pigment.

Morphology. Prosoma: anterior margin of carapace not emarginated, but slightly convex. Carapace acarinated and smooth; median ocular tubercle anterior to the centre of the carapace; median eyes separated by more than two ocular diameters. Three pairs of lateral eyes, the third pair reduced. Mesosoma tergites smooth with one vestigial median carina. Tergite VII pentacarinate with all carinae vestigial. Sternites smooth, acarinated with short linear spiracles. Pectines long; pectinal tooth count 36-36; fulcra weakly marked; basal middle lamella strongly dilated. Metasoma: segments I to IV with 10 carinae, moderately crenulated; ventral carinae marked with spinoid granules on segments II and III. Segment V with five carinae; ventromedian carinae strongly marked, with lobate denticles; anal arc composed of nine to 10 strongly reduced ventral teeth and two uniform lateral lobes. Dorsal furrows of all segments shallow and smooth; intercarinal spaces weakly granular to smooth. Telson strongly granular; vesicle with a pear-like shape, and a long aculeus longer than vesicle; subaculear tooth absent. Chelicerae with a single denticle at the base of the movable finger [7]. Pedipalps: trichobothrial pattern orthobothriotaxic, type A; trichobothrium d1 of femur displaced over the external face of the segment [5]; dorsal trichobothria of femur in α (alpha) configuration [8]. Femur pentacarinate; carinae weakly crenulate. Dorsointernal carinae of patella with two to three spinoid granules; other carinae vestigial. Chela smooth and acarinate with moderately elongated fingers. Dentate margins on movable and fixed fingers composed of nine to 10 linear rows of small granules almost forming a single row; outer and inner accessory granules absent on both fingers; two very small granules located proximally to the terminal granule on the movable finger. Legs: ventral aspect of tarsi with two series of moderately long setae. Tibial spurs present on legs III and IV, moderately marked. Pedal spurs present on all legs, weakly to moderately marked.

Geographic distribution: only known from the type locality.

Morphometric values (in millimeter) of the female holotype. Total length: 22.19 (including telson). Carapace: length, 2.64; anterior width, 1.78; posterior width, 2.71. Mesosoma length, 7.42. Metasomal segments. I: length, 1.57; width, 1.43; II: length, 1.64; width, 1.36; III: length, 1.78; width, 1.28; IV: length, 2.07; width, 1.21; V: length, 2.43; width, 1.28; depth, 1.21. Telson: length, 2.64; width, 1.00; depth, 1.00. Pedipalp: femur length, 2.28, width, 0.64; patella length, 2.64, width, 0.92; chela length, 4.14, width, 0.71, depth, 0.86; movable finger length, 2.85.

5 Biogeographical considerations on the Saharan and peri-Saharan scorpion fauna

In their earlier discussion, Lourenço and Duhem [1] pointed out that the present composition of the Sahara and peri-Saharian faunas is, in fact, the heritage of ancient faunas present in North Africa since Early or, at least, Middle Cenozoic times [3]. North Africa has experienced numerous paleoclimatological vicissitudes during the last few million years, some even in more or less recent Quaternary periods. Sahara has undergone a series of wet periods, the most recent occurring 10 000–5000 years BP. It was not until about 3000 years BP that the Sahara assumed its present arid state [9]. Even though recent studies suggest that the Sahara desert may be much older than was previously thought [10], it seems reasonable to postulate that extremely arid areas have always existed as patchy desert enclaves, even when the general climate of North Africa enjoyed more mesic conditions.

In these arid and desert regions of the North African Sahara, a specialized scorpion fauna would have evolved in response to the aridity. The ‘ancient lineages’ become adapted to arid conditions and undoubtedly correspond with many extant groups some of which are typically psammophilic. It is important to emphasise the fact that these lineages must have been present in North Africa for at least 10 to 15 MY [11,12]. In contrast, other lineages less well adapted to aridity and, previously, only present in more mesic environments, have regressed markedly in their distribution with the expansion of the desert. These populations are, in several cases, now reduced to very limited and patchy zones of distribution, sometimes with remarkable disjunctions in their biogeographic patterns.

The present patterns of distribution observed among North African scorpions can be summarized in three more or less defined models. A core Saharian region [3], defined as the ‘central compartment’, in which only the groups best adapted to xeric conditions are distributed. The peri-Saharian region which surrounds most of the central compartment. A typical element present in this region is the genus Butheoloides, Hirst, 1925 [13,14]. In this zone, remarkable disjunctions can occur, such as the one presented by the genus Microbuthus, Kraepelin, 1898 (for details, refer to Lourenço and Duhem [15]). In other cases, relictual endemic lineages can also be detected. In the case of the third geographical model, several groups, more or less well adapted to aridity, have their populations limited to zones of refugia. In the Saharan regions, these refugia are represented by massifs, such as Hoggar, Aïr and Adrar. Examples of endemic genera in these zones are Cicileus, Vachon, 1948; Lissothus and Pseudolissothus [3,16,17].

The new genus and species described here corresponds better to the model of the endemic and relictual elements found in the peri-Saharan region. The new species was collected in a zone of desert shrub and grass and does not show the characteristics of a psammophilic element. Even if this area of the Great Rift Valley, distributed in North of Kenya and South Ethiopia, is very arid, it does not really correspond to a desert area (desert areas do exist east of Lake Turkana). Other endemic scorpions have already been described from the region of the Great Rift Valley, e.g. Butheoloides polisi, Lourenço, 1996; Uroplectoides abyssinicus, Lourenço, 1998 and Neobuthus cloudsleythompsoni, Lourenço, 2001, attesting therefore of the existence of an important local diversity [18,19].

Acknowledgements

We are most grateful to Elise-Anne Leguin, Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris for her contribution in the preparation of the plates.