1 Introduction

In the development field, homeosis certainly is one of the most spectacular effects that a mutation can cause: in homeotic mutants, at a given position, the identity of an entire organ is replaced by that of another organ. These phenotypes, which had been noticed by botanists since antiquity, were explained in animals by the misexpression of conserved transcription factors, called homeoproteins, exhibiting a common helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain, the homeodomain. Homologs in plants were identified [1–3]. While the role of the plant homeoproteins in homeosis turned out to be rather scarce, this family of ca. 105 members in Arabidopsis contains among the most crucial effectors of plant development. In this review, we will focus on a particular class of homeoproteins, the three-amino-acid-loop-extension (TALE) homeoproteins, which contain a three-amino acid extension in the loop connecting the first and second helices of their homeodomain [4–6].

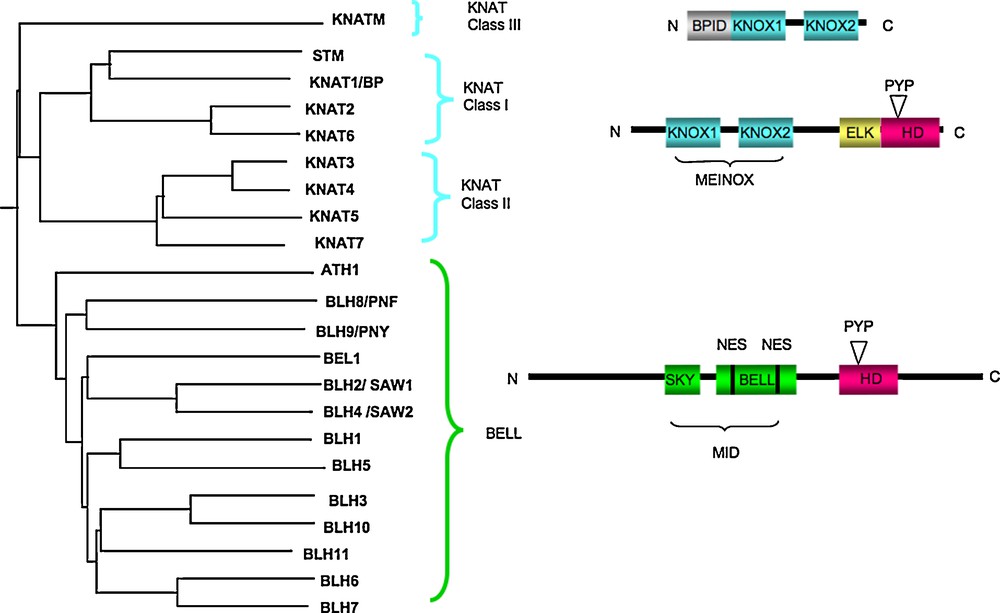

The plant TALE homeodomain superclass comprises the KNOTTED-like homeodomain (KNOX) and BEL1-like homeodomain (BELL) proteins that are structurally and functionally related (Fig. 1). As observed for the animal TALE homeoproteins MEIS (including vertebrate Meis and Prep, fly Homothorax (Hth) and worm Unc-62) and PBC families (vertebrate Pbx protein, fly Extradenticle Exd and worm Ceh-20), the KNOX and BELL proteins function as heterodimers and have evolved a complex regulatory mechanism controlling their subcellular localization (Box 1).

The TALE proteins: dissecting their sequences. A. Phylogeny of the TALE superfamily. B. Schematic structures of the KNAT and BELL proteins; KNAT proteins contain a MEINOX (from MEIS “Myeloid ecotropic viral integration site” and KNOX) domain composed of two subdomains, KNOX1 and KNOX2, separated by a flexible linker, an ELK domain and a TALE homedomain which has three-extra-amino-acids (Proline [P]-tyrosine [Y]-Proline [P]) between the first and the second helix. The MEINOX domain mediates interactions with other KNOX and TALE proteins. The KNATM protein has no homeodomain. KNATM interacts with BELL proteins through the MEINOX domain and interacts with BP via the BPID (BP interacting domain). BELL proteins contain a TALE homeodomain, a MID (MEINOX interacting domain) composed of the SKY and BELL regions. The BELL domain harbors two nuclear exclusion leucine-rich sequences (NES) involved in the interaction with KNOX proteins and with the nuclear export receptor atCRM1.

Genetic and molecular analyses have revealed overlapping and distinct functions for the TALE proteins during plant development. In this review we aim at precisely dissecting these functions during the main steps of the plant post-embryonic life. For this purpose, we will mostly focus our survey on data from Arabidopsis, and in some specific cases from other species.

2 TALE proteins control the establishment and maintenance of the shoot apical meristem

Shoot apical meristems (SAM) are populations of dividing undifferentiated cells that generate lateral organs at the apices of stems and branches throughout the life of a plant (for a detailed review on the SAM, see [7–10]). As it balances two opposing functions, organ production and self-maintenance, the SAM is one of the most dynamic structures in biology. In the past two decades, developmental biologists have turned to molecular genetics to determine the molecular basis of SAM functions and identified keys effectors involved in transcriptional regulation and hormonal signaling, the TALE proteins having a major position in this framework.

2.1 TALE proteins display various levels of contribution to meristem establishment and maintenance

In Arabidopsis, the KNOX family is divided in three classes (Fig. 1): class I KNOX genes are mainly expressed in the meristematic tissues, and include SHOOTMERISTEMLESS (STM), BREVIPEDICELLUS (BP)/KNAT1, KNAT2 and KNAT6. Class II KNOX genes are broadly expressed and comprise KNAT3, KNAT4, KNAT5 and KNAT7. Class III contains a unique member, KNATM, which produces three isoforms by alternative splicing [11]. KNATM is expressed in the organ primordia and at the boundary of mature organs and is excluded from the SAM. In contrast to other KNAT genes, KNATM is found only in dicots [11]. KNATM protein has no homeodomain, but interacts with BELL proteins through its MEINOX domain and dimerizes with BP through an acidic coiled-coil domain named BP-interacting domain (BPID) ([11] and Box 1). Thus, KNATM may regulate transcription independently of the homeodomain through the titration of other TALE proteins or as a transcriptional cofactor [11].

The BELL family comprises 13 members (Fig. 1, Table 1 and Box 1). So far a function has only been proposed for BELL1 (BEL1) the founder of the family, PENNYWISE (PNY), also known as BELLRINGER (BRL), REPLUMLESS (RPL), VAAMANA (VAN) or LARSON (LSN), POUND-FOOLISH (PNF) a close relative of PNY, SAWTOOTH1 (SAW1), SAW2 and ARABIDOPSIS HOMEOBOX 1 (ATH1) [12–22].

TALE genes expression.

| Gene name | Accession Number | Expression pattern | Refs. |

| STM | At1g62360 | Embryo, SAM, IM, axillary meristems, FM, carpel | [16,25,124] |

| BP/KNAT1 | At4g08150 | SAM, IM, stem (cortex), pedicel, style, base of lateral roots | [13,113,125,126] |

| KNAT2 | At1g70510 | Embryo, root, SAM, FM, and carpel | [30,36,61,93,127] |

| KNAT6 | At1g23380 | Embryo, root, SAM, FM, flower, and carpel | [30,93,128] |

| KNAT3 | At5g25220 | Expressed in most tissues. In elongated zone of the mature root (pericycle, endodermal and cortical cells) | [111,113] |

| KNAT4 | At5g11060 | Almost every organ. Root (phloem, pericycle cells and endodermis). | [111,113] |

| KNAT5 | At4g32040 | Almost every organ. Elongation and differenciation zones of the main root (epidermis) | [111,113] |

| KNAT7 | At1g62990 | Xylem | [110] |

| KNATM | At1g146760 | Organ primordia, leaves and FM | [11] |

| BEL1 | At5g41410 | Integument of ovule, IM and FM, leaves, sepals | [12,19,121] |

| ATH1 | At4g32980 | SAM, young leaves, flowers: stamens, carpels | [20,21,129] |

| BLH1 | At2g35940 | Transmitting track and funiculus, | [108] |

| BLH2/SAW1 | At4g36870 | Leaves, sepals, petals, anther filament, style, transmitting track, stem | [19] |

| BLH3 | At1g75410 | IM FM | [31] |

| BLH4/SAW2 | At2g23760 | Cotyledons, leaves, sepals, anther filament, style, transmitting track, stem | [19] |

| BLH5 | At2g27220 | Unknown | |

| BLH6 | At4g34610 | Embryo, IM, flowers: anthers, stigma | [130] |

| BLH7 | At2g16400 | Unknown | |

| BLH8/PNF | At2g27990 | SAM, IM, FM | [13,14] |

| BLH9/PNY/BLR/RPL/VAN/LSN | At5g02030 | SAM, IM, FM, stem, replum | [13–16] |

| BLH10 | At1g19700 | Unknown | |

| BLH11 | At1g75430 | Unknown |

Strong alleles of stm mutants fail to form a meristem and to produce lateral organs. Based on this phenotype, a role for STM in meristem initiation during zygotic embryogenesis, and maintenance during the post-germinative growth has been proposed [23–25]. Consistent with these genetic data, STM is expressed in the SAM, except in the initium, the site where a new organ is initiated. The ortholog of STM in maize, KNOTTED1 (KN1), is the founder of the KNOX subfamily and when disrupted also leads to defects in meristem maintenance [26–28].

The role of four other TALE genes, namely BP, PNY, KNAT6 and ATH1 in SAM initiation and maintenance has also been demonstrated by the observation that their inactivation aggravates the weak stm allele phenotypes [13,14,16,22,29,30]. The contribution of PNF to the SAM function is only found in the absence of PNY or both PNY and ATH1 and is likely due to the fact the STM protein requires these factors to become nuclear [22,31].

2.2 Dissecting the contributions of Class I KNOX genes in the different domains of the SAM

Due to its pattern, STM has become a marker of meristematic cell identity. Within the SAM, three subdomains, all expressing STM, can be distinguished based on histological, genetic and functional features (for a review, see [7,9,10]). First, the central zone, with CLAVATA 3 (CLV3) as a genetic landmark, contains the population of slowly dividing stem cells of the meristem. The peripheral zone surrounds the central zone and, thanks to a higher rate of proliferation, provides the cells required for lateral organ formation. In the tornado2 (trn2) mutant, the STM expression domain is increased but the markers of the central zone are not affected, suggesting that TRN2 specifically regulates the meristematic identity in the peripheral zone, thus uncoupling STM functions in both domains [32]. TRN2 encodes a tetraspanin-like membrane protein, a family of proteins that has been shown to contribute to signal transduction in animals. A similar function in plants is supported by the fact that TRN1, a Leucine-rich repeat protein, belongs to the TRN2 pathways as well [33].

Last, the third subdomain of the meristem is the boundary, a domain that separates the meristem sensu stricto from the growing primordium, and which can be spatially defined by the pattern of the CUP-SHAPED COTYLEDON (CUC) mRNA. There is accumulating evidence suggesting that this domain contains cells that promote meristematic identity, while undergoing major morphogenetic changes. In particular, the CUC proteins activate the expression of STM as well as other class I KNOX genes and repress growth in the boundary of organ primordia to allow organ separation [30,34]. Consistent with this, double mutants in two of the three CUC genes exhibit cotyledon fusions and stm strong alleles display a fusion of the cotyledon petioles, thus revealing defects in organ separation from the meristem [24]. A contribution of PNY, KNAT6, ATH1 and PNF in organ separation has also been shown [18,21,22,30]. Conversely, the ectopic expression of class I KNOX genes extends the undifferentiated state of the cells beyond the meristematic domain [35,36].

2.3 A mechanism: TALE proteins regulate hormonal pathways to maintain meristematic cells in an undifferentiated state

The redundant function of the KNOX proteins in meristematic cell maintenance has been correlated to their shared function in controlling the homeostasis of cytokinins (CKs) and gibberellins (GAs) (for a review, see [37]). CKs are plant hormones involved in cell proliferation while GAs notably control leaf morphogenesis [38–41]. The activation of KNOX proteins leads to an increase of CK biosynthesis by up-regulating the accumulation of AtIPT7 mRNA levels, and to the activation of a type-A ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR 5 (ARR5), a CK response factor. Conversely, plants overproducing CKs have higher levels of BP/KNAT1 and STM mRNAs and can rescue the stm mutant [42–45].

In addition to their impact on CKs, KNOX proteins have been shown to negatively regulate GA biosynthesis through direct transcriptional repression of the GA-biosynthesis gene GA 20-oxidase [46–48]. Consistent with these data, exogenous GA partially suppressed the phenotype induced by KN1 and KNAT1 overexpression ([47], see next sections). Conversely, the stm phenotype was enhanced in the constitutive GA signaling mutant spindly. Furthermore, both KNOX proteins and CKs activate a GA-2 oxidase gene triggering GA catabolism, thereby excluding GAs from the SAM [43]. Thus, the maintenance of the SAM by KNOX proteins involves the regulation of both CKs and GAs pathways.

In addition to the crosstalks between TALE and CKs or GAs, SAM maintenance relies on a complex network involving other regulators of stem cell and hormone signaling as well. For instance, the stem cell maintenance involves a network with several feedback loops where CK plays a central role. CKs simultaneously activate the homeodomaine protein WUSCHEL (WUS) and repress CLV1 [49] [50]. Besides, the disruption of a type A ARR, a negative response regulator of CKs, in the maize aberrant phyllotaxy 1 (abph1) mutant leads to an enlarged meristem, a phenotype which could be associated with increased KN1 expression levels, at least in the embryo [51,52]. Interestingly, ABPH1 has also been shown to act as a positive regulator of PINFORMED (PIN) expression and auxin levels [53]. This is consistent with the phyllotactic defects observed in the abph1 mutant (see next sections for a discussion on auxin and phyllotaxis). To summarize, while the crosstalks between the TALE and CKs and GAs play a crucial in SAM maintenance, further work is required to integrate other factors, like WUS and auxin, in this network.

3 Downregulating TALE expression at sites of organ initiation

KNOX proteins are crucial to maintain a population of undifferentiated cells in the SAM and thus to prevent cells from being recruited too early in the primordium. In the initium, the KNOX genes are repressed to allow the exit of organ founder cells from the SAM. Organ emergence is then associated with an increased growth rate and cell expansion. Several hormones, including GA, ethylene and auxin have been shown to control these responses [37,54].

Recent evidence suggests that auxin may play a major role in downregulating KNOX genes during organ emergence. The auxin transport inhibitor naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) induces KNOX ectopic accumulation in maize leaf primordia [55]. Disruption of auxin efflux in the pin1 pinoid double mutant also de-repressed STM expression [56]. Interestingly, the defects in leaf formation in mutant in auxin transport (pin-formed1 (pin1) or auxin signaling (axr1) were enhanced in pin as1 or axr1 as1 double mutants and were associated with the ectopic expression of BP. The reduction in leaf number of the pin1 mutant was partially rescued by BP inactivation, suggesting that the auxin dependent repression of KNOX genes is required for primordium formation [57]. It is not known whether the KNOX downregulation in the incipient primordium is maintained in these mutants. The finding of a correlation between auxin maxima and the initial downregulation of KNOX genes in the incipient leaf primordium suggests that this is the case [58,59], but further genetic analyses are required to demonstrate this conclusively. The JAGGED LATERAL ORGAN (JL0) protein, which is required to maintain the boundary domain, may play a central role as it coordinates KNOX and PIN activity [60].

Ethylene may be involved in regulating SAM activity since an antagonistic interaction between KNAT2 and ethylene has also been reported [61]. The domain of KNAT2 expression was restricted in the presence of ethylene and in the constitutive triple response 1 (ctr1) mutant, but enlarged in the ethylene insensitive mutant ethylene response 1 (etr1). The KNAT2 overexpressor phenotype was partially rescued by the application of an exogenous ethylene precursor and in the ctr1 mutant. Conversely, overexpression of KNAT2 increased the number of cells in the SAM of ctr1 [61].

To conclude, several clues point to a hormone-dependent downregulation of KNOX genes in the incipient primordium. The identity of the genetic factors responsible for this control is still unknown.

4 TALE expression shapes the leaf

4.1 KNOX expression is regulated during leaf growth

In Arabidopsis, the expression of class I KNOX genes is not detected in growing leaves and their ectopic expression leads to abnormal leaf morphologies, such as patterning defects and pronounced lobes [2,62]. Several regulators have been shown to maintain the repressed state of the class I KNOX genes in the Arabidopsis leaf. These regulators are presented below. Importantly, they are specifically involved in controlling KNOX expression after the leaf has emerged; none of them repress the KNOX genes in the incipient primordium.

Screens for mutants resembling KNOX overexpressors have led to the identification of ASYMMETRIC LEAVES 1 (AS1), a MYB transcription factor, and AS2, a member of the lateral organ boundaries-domain (LOB) protein family, which specifies adaxial fate. AS1 and AS2 down-regulate the class I KNOX genes but not STM in leaves and conversely, STM represses AS1 expression in the SAM [63,64]. Enhancers of as2 have been isolated and found to encode two key regulators of gene silencing: RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase 6 (RDR6) and ARGONAUTE 1 (AGO1). Rdr6 as1 and rdr6 as2 double mutants produce more lobed leaves, a phenotype, which is associated with the ectopic expression of BP and an increase of miRNA 165/166 levels [65]. These miRNAs regulate class III HD-Zip mRNAs that contribute to adaxial-abaxial leaf polarity. SERRATE, a zinc finger protein that regulates expression of the HD-Zip III gene PHABULOSA (PHB) via a microRNA (miRNA) gene-silencing pathway, and PICKLE, a chromatin-remodeling enzyme, seem to limit the ability to respond to KNOX activity in leaves [66,67]. Similarly, ago1 as2 double mutants display more lobed leaves and exhibit ectopic expression of all class I KNOX genes [68]. These results show that the AS1 AS2 pathway, together with RDR6 and AGO1, repress KNOX genes in leaves. Genes involved in abaxial organ identity, such as the YABBY genes, also repress KNOX class I genes, including STM, on the abaxial sides of leaves [69].

A genetic analysis identified two regulators that specifically repress the expression of the class I KNOX genes in the proximal region of the leaves: the BLADE ON PETIOLE1 (BOP1) and BOP2 genes encode proteins with ankyrin repeats and a BTB/POZ domain. They are expressed in the proximal domain of lateral organs, where they repress the BP/KNAT1 KNAT2 and KNAT6 genes [70–72].

Last, the SAWTOOTH1 (SAW1) and SAW2 proteins, two other BELL members act antagonistically to BP, KNAT6 and STM in the leaf to regulate leaf margin shape ([19], see next section).

The repression of the KNOX genes involves the chromatin state: a model suggests that AS1/AS2 complexes bind to two distinct sites of the BP promoter, create a DNA loop between the two binding sites and recruit the chromatin-remodeling protein HIRA to maintain the chromatin in a stable repressive state [65,73]. Furthermore, the Polycomb-Groups proteins CURLY LEAF (CLF) and FERTILISATION-INDEPENDENT ENDOSPERM (FIE) maintain the repressed state of KNOX genes in leaves by catalyzing the dispersed trimethylation of histone H3 at Lysine 27 (H3K27) and subsequently inducing chromatin compression and inhibition of transcription [74–76].

4.2 De-repression of KNOX genes in the leaf, or how to make leaflets

Leaf shape, and notably the formation of leaflets, is controlled by various pathways (see, for reviews, [77], Hasson et al. in this issue, and [78]). The presence of lobed leaves in KNOX overexpressor lines has suggested an important role of these genes in the formation of compound leaves [2,62]. A study of KNOX class I genes expression in various vascular plants revealed a correlation between KNOX expression and leaf shape [79]. As in species with simple leaves, KNOX class I genes are downregulated at the sites of leaf primordium initiation in the compound leaves, but are subsequently reactivated in the leaves to promote the formation of leaflets. The molecular control of leaflet formation in compound leaves seems very close to that of organ initiation at the periphery of the SAM. The molecular basis of leaflet initiation was investigated in more detail in Cardamine hirsuta (C. hirsuta), a wild relative of Arabidopsis with dissected leaves [80]. Similar to the leaf initiation at the SAM, the lateral formation of leaflets requires STM activity, which delays cellular differentiation, and the auxin efflux carrier PIN1, which generates local auxin maxima to promote leaflet formation [81]. Promoter-swap experiments indicated that the differences in BP and STM expression between Arabidopsis and C. hirsuta were associated with differences in promoter cis regulatory sequences [80]. More generally, the current model for the molecular basis of compound leaves is the presence of a cis regulatory polymorphism that would generate the diversity of the leaf morphology [73]. A cis regulatory sequence called the K-box, which is involved in the downregulation of STM in developing leaves but not in emerging primordia in Arabidopsis, has been identified in both monocots and dicots [82]. In this framework, however, the K-box most probably has a minor role in dissecting leaves in Cardamine, since it is present in both Arabidopsis and Cardamine [82].

The recent discovery of the new KNOTTED member, KNATM, in Arabidopsis and its homolog PETROSELINUM (PTS) in the tomato, has revealed an additional mechanism to regulate leaf margins [11,83]. In Arabidopsis, the two BELL members SAW1 and SAW2 redundantly repress BP, KNAT6 and STM in the leaf [19]. KNATM, which is also expressed in the hydathodes acts antagonistically to SAW1 and SAW2 as its overexpression mimics the saw1 saw2 increased leaf serration phenotype [11,19]. Because it interacts with SAW proteins, KNATM has been proposed to modulate SAW1 and SAW2 activity by titration [11]. Studies on different accessions of tomato from the Galapagos Islands, which exhibit variation in leaf shape, showed that the level of PTS correlates with leaflet formation [83]. The PTS protein binds to BIP (the SAW tomato ortholog) and thus inhibits both its nuclear localization and its interaction with leT6 (the STM ortholog of tomato). Thus high levels of PTS lead to an increase of the tomato KNOTTED1 TKN1 (the tomato BP ortholog) gene expression and renders LeT6 available to modulate leaf shape on its own or via the interaction with another partner.

To summarize, an intricate network of factors involved in transcriptional patterning, silencing and chromatin state regulates the expression of KNOX genes in the growing leaf. Together with other factors they control leaf morphogenesis and more specifically, leaflet formation.

5 TALE proteins control plant architecture

Organ emergence is a process that is integrated at the level of the whole plant. In particular, the emergence of an organ at a given position impacts the position of the following organs. This generates a pattern along the stem, which is called phyllotaxis. Several models involving a feedback loop between auxin and PIN1 localization are consistent with phyllotaxis emerging from a local cell-based response to auxin concentration or flux [58,59,84–86]. As shown earlier the link between auxin and the TALE proteins appears rather indirect. Because STM or KN1 are downregulated at the sites of incipient primordium, their expression pattern predicts the position of the organs in the SAM, and thus the phyllotaxis [87]. However, knowing the major impact of STM or KN1 disruption on the SAM itself, it remains difficult to infer a function in phyllotaxis from the mutant phenotypes only.

It must be noted that phyllotaxis not only results from the pattern initiated in the SAM, but also from the subsequent growth during stem development [88,89]. In this respect, while the SAM structure of the pny and bp mutants appears normal, major phyllotactic defects are observed in these mutants [13,14] (Peaucelle, personal communication). Notably, the pny mutants display internodes with irregular sizes and clusters of organs and bp mutants exhibit reduced internode lengths [13,14,90,91]. Mechanistically, BP regulates lignin deposition during internode development to prevent cambium-derived cells from differentiating into lignified xylem tissue. This further confirms the patterning role of this gene during the post-meristematic phase [13,90–92].

In addition, removal of KNAT6 activity suppresses the pny phenotype and partially rescues the bp phenotype. The suppression of the aberrant organ positions in knat6 pny double mutant is likely attributable to the misexpression of KNAT6 in pny pedicels as the downregulation of KNAT6 is maintained in pny inflorescence meristems. Removal of KNAT2 activity has an effect only in the absence of both BP and PNY [93]. Further studies involving other TALE heterodimers have indicated that PNY/PNF, PNF/BP, PNY/STM and PNF/STM heterodimers regulate internode patterning or phyllotaxis [18,94].

6 TALE proteins regulate the transition to flowering

The control of the transition from vegetative to reproductive growth integrates environmental (temperature, day-length) and endogenous signals. The so-called autonomous pathway involves an array of regulators that promote flowering independently of day-length, via the downregulation of the floral repressor FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC). In addition, the impact of day-length on flowering involves FT, a promoter of flowering under long days, which is repressed by FLC [95–97].

The BELL protein ATH1 has been shown to act as a floral repressor regulating FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) expression levels [20]. Antagonistic roles for two other BELL members in flower transition has been suggested, as plants overexpressing BELL-like HOMEODOMAIN 3 (BLH3) are flowering early and plants overexpressing BLH6 are delayed in flowering [31]. Double mutants in which both PNY and PNF activities are compromised do not flower and show reduced levels of LEAFY (LFY), APETALA1 (AP1) and CAULIFLOWER (CAL) transcripts [18,98]. Conversely, AG has been found to be a direct target of PNY [17]. Consistent with this, ectopic expression of LFY restores flower formation in pny pnf double mutant. In contrast, ectopic expression of FT in pny pnf could not activate the floral meristem identity genes and thus promote flower specification suggesting that FT may require the function of PNY and PNF to initiate flower formation [98]. In addition to this function, PNY and PNF function in parallel with LEAFY, UNUSUAL FLORAL ORGAN and WUSCHEL to regulate flower identity [99]. Interestingly, PNY acts as repressor of flowering when interacting with ATH1, whereas it acts as a positive regulator of flowering when interacting with PNF [18,22,98].

To conclude, several BELL members have been shown to control the transition from vegetative to the reproductive phase. How the network operates is not completely elucidated, but the identification of direct targets, like AG for PNY, should help integrate these members in the larger flower transition network.

7 TALE proteins control ovule and fruit development

In contrast to the shoot apical meristem, the flower meristem is a determinate structure (i.e. it produces a limited number of organs) [100]. Meristematic activity ceases after the initiation of the last floral organs, the carpels. Later, carpels differentiate in turn a specialized meristematic tissue, the placenta, which lies along the inner side of the replum and which produces ovules. Consistent with this, STM, BP and PNY are expressed in the replum and it was found that AS1 restricts BP expression to the replum to promote correct valve differentiation, further suggesting the presence of conserved regulatory mechanisms for TALE proteins between the shoot meristem and the carpel [101]. From their mutant phenotype, PNY and BP promote replum identity [15,101]. In contrast, KNAT6 is expressed in the boundaries between the replum and the valves and its inactivation suppresses the replum defect seen in pny and in bp pny [93]. This further illustrates distinct and antagonistic interactions between these members.

The BEL1 gene is expressed in ovule integument primordia and controls integument ovule identity [12]. The bel1 mutant exhibits bell-shaped ovules caused by the absence of a true integument [102,103]. Recently it has been shown that BEL1 interacts with several MADS-box factors to control cell fate in ovule primordia [104]. Interestingly, some of the abnormal integuments in bel1 are converted into carpeloid structures [102,103]. Overexpression of KNAT2 and STM also leads to the homeotic conversion of ovules into carpeloid structures and missexpression of BP/KNAT1 alters outer integument morphology [36,105,106]. As the class I KNOX genes are not expressed in ovules and knowing that BEL1 interacts with STM and KNAT2 in yeast two-hybrid assays, it is likely that when overexpressed they disrupt the interaction between BEL1 and the MADS factors. Similarly, a KNOX-BELL heterodimer has been involved in embryo sac development as well. In the blh1/eostre-1 mutant, two egg cells are formed instead of place of one, and one synergid cell is missing. Two-hybrid studies revealed that KNAT3 forms heterodimers with BLH1 [107,108]. Consistent with this, the inactivation of KNAT3 rescues the embryo sac defects of eostre 1 mutant [108]. The exact role of the BLH1-KNAT3 heterodimer in embryo sac development is, however, indirect since BLH1 is not expressed in the embryo sac.

8 Concluding remarks: further TALES for TALES!

In the past two decades, progress has been made towards elucidating the role of TALE proteins in plant development. These proteins regulate many aspects of plant development and have overlapping, distinct, and in some cases antagonistic activities (Fig. 2).

TALE proteins involvement throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle: (SAM: Shoot apical meristem; IM: Inflorescence meristem; FM: Floral meristem). This figure summarizes the different functions of 9 TALE proteins (out of 21) at each step of Arabidopsis life. For further detail, see text.

However, the functions for half of the TALE members remain unknown. In particular, our knowledge of the KNAT class II members is very limited except for KNAT7 for which a role in secondary wall biosynthesis has been proposed [109,110]. KNAT3, KNAT4 and KNAT5 are expressed in the root but their role remains unclear as loss-of-function mutants and overexpressors for KNAT3, KNAT4 and KNAT5 have wild-type phenotypes [111–113]. Their function may be obscured by redundancy with other factors within the TALE family.

Alternatively, investigation of the functions of the TALE proteins in specific cell types or species could reveal new and/or specific TALE dependent mechanisms. This was recently illustrated in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii where a KNOX ortholog present in the minus gamete and a BELL ortholog present in the plus gamete heterodimerize in the zygote to activate its developmental program [114]. From an evolutionary perspective, this also shows that, while the TALE proteins are associated with meristem activity in flowering plants, they have other roles in their ancestors. This is also true in multicellular organisms: TALE orthologs have been found to control sporophytic development in the moss Physcomistrella patens, despite the absence of a meristem during this phase [115,116].

While molecular genetics approaches have been successful in unraveling TALE functions, the exact cellular mechanism behind their morphogenetic function remains unclear. The regulation of TALE functions seems to involve an elaborate mechanism that controls TALE protein localization between cells. In particular, microinjection and graft experiments showed that the KN1 protein could move through the plasmodesmata and transport its own mRNA [117]. Furthermore, the microtubule-associated Movement Protein Binding Protein 2C binds to the homeodomain of KN1 and prevents KN1 from moving from cell to cell by restricting its accessibility to plasmodesmata [118]. Last, complementation experiments have shown that KNOX proteins differ in their trafficking ability. Movement was observed for STM and BP, although BP was less motile, but not for KNAT2 and KNAT6 [119,120]. The exact role of this intercellular motility and putative KNOX gradient remain to be elucidated. Inside the cell, OVATE proteins have been shown to interact with KNOX-BELL heterodimers and the cytoskeleton to move the TALE complex from the nucleus to the cytoplasm [107].

The mechanisms and implications behind the spatial control of the TALE proteins in tissues are still far from being completely elucidated. Since these proteins function as heterodimers, it will be essential to determine the exact localization of BELL-KNOX dimers and to identify their specific and overlapping targets to further understand their role. This network becomes even more complex considering that each protein can have distinct protein partners and the resulting heterodimers can exhibit contrasting activities.

More generally, the elucidation of the different layers of regulations and interactions of the TALE proteins has built one of the best documented gene networks in plant development. The flip side is that this network reaches such a level of complexity that it will become increasingly difficult to address its functions, dynamics and interactions using traditional approaches. Prospects for future research should thus involve the integration of the TALE functions in the larger gene regulatory network in virtual tissues using systems biology approaches.

Acknowledgements

We thank Patrick Laufs and Elisabeth Crowell for a critical reading of the review.