1 Introduction

Nitrogen fertilization is the most important management strategy to improve agricultural crops. Nitrate and nitrite are essential nutrients for plants protein synthesis and play a critical role in nitrogen cycle [1]. Thus, the form of N supply may exert a profound influence on plant growth and metabolism and play a key role in the cation-anion relationships in plants [2,3]. Nitrate is a vital nutrient for plants [4], however, nitrite (NO2−) in soils has been observed under a variety of field conditions. It is possibly originated during nitrification or denitrification depending on the soil conditions [5]. Furthermore, the uptake of nitrite into the plastids and its subsequent reduction are potentially important control points that may affect nitrate assimilation [6].

Some studies succeeded in measuring nitrate and nitrite contents in soils and in some leguminous vegetables and suggested that the studied area were possibly polluted due to excessive usage of fertilizers. Toxic concentrations of nitrogen fertilizers cause characteristic symptoms of nitrite toxicity in plants. Besides, the oxides of nitrogen emitted into the atmosphere in combustion from various industries come down as dry or wet deposition (acid rain) onto the soil and lower the soil pH. Thus, increased acidity of soil results in several effects in plants, nitrate and nitrite bacteria are reduced while ammonifying bacteria are increased in the soil disturbing the nitrogen cycle [7].

Recent work established a gradual increase of nitrite accumulation in soil layers. Such nitrite accumulations in the topsoil layer become a threat to the agro-ecosystem [7]. Thus, phytotoxicity of NO2− has been demonstrated in a wide range of species. Tomato is regarded as one of the most sensitive of glasshouse crops to nitrogen oxides [8]. It was demonstrated that increasing NO2 concentration suppressed plant biomass yield, with breakdown of vascular tissue restricting cations uptake [9,10]. Tight correlations between nutrient's concentrations, uptake, xylem and phloem flow and the resulting partitioning of elements were observed in Castor bean [11].

Other studies have suggested that plant cells, as animal cells, produce reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in addition to active oxygen species [12,13]. There have been a number of studies indicating that plant cells possess a nitrite – dependent NO production pathway which can be distinguished from the NOS – mediated reaction. In fact, nitrate reductase (NR) is capable of producing three types of toxic molecules (e.g. NO, O2−, ONOO−) when nitrite, the normal NR reaction product, is provided as substrate [14]. It has been shown that NO production was mainly located in both phloem and xylem regardless of the cell differentiation status. However, there was evidence for a spatial NO gradient inversely related to the degree of xylem differentiation [15]. These findings suggest that the phloem perceives and produces stress-related signals and that one mechanism of distal signaling involves the production and transport of NO in the Vascular tissue [16].

In previous work [17], we showed that increasing nitrite levels in the culture medium led to several disruptions in tomato organs, including growth inhibition, chlorosis, nitrite and ammonia accumulation associated with the appearance of oxidative stress symptoms. While, it is not yet clarified if nitrite effects on growth were related to disturbances in nutrient uptake and accumulation in tomato tissues. In this work, special attention was given to KNO2 effects on nitrate uptake, translocation and cations (K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) accumulations in relation to stem structural modifications.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and growth conditions

Seeds of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill. cv. Ibiza F1) were sterilized in 10% (v/v) H2O2 for 20 minutes. The seeds were then thoroughly washed with distilled water and germinated on moistened filter paper at 25 °C in the dark. Uniform seedlings were then transferred to continuously aerated standard nutrient solution (pH 6.0) [17] containing 0.5 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM KH2PO4, 0.25 mM CaCl2, 1 mM KNO3 100 μM Fe-K-EDTA, 30 μM H3BO3, 5 μM MnSO4, 1 μM CuSO4, 1 μM ZnSO4, and 1 μM (NH4)6Mo7O24. After an initial growth period of 10 days, nitrogen was added to the nutrient solution at various concentrations (0.25; 1; 2.5; 5; 10 mM). To keep constant the nutrient composition and pH, solutions were renewed every 3 days. Plants were grown and treated with NO2 in a growth chamber (26 °C/70% relative humidity during the day, 20 °C/90% during the night). The photoperiod was 16 hours daily with a light irradiance of 150 μmol/m2 S−1 at the canopy level. After 7 days of nitrite (KNO2) treatment, plants were separated into shoots and roots. Roots were rapidly washed in distilled water, and all samples were either dried to constant weight at 70 °C or stored in liquid nitrogen for later analysis. The data are averages of six biological replicates.

2.2 Analytical determinations

2.2.1 Measurements of NO3 and NO2 in the xylem exudates

For collection of xylem exudates, these plants were decapitated as the mesocotyl. The entire root system was fixed in a pressure bomb mechanism described by [18], contained 150 ml of hydroponic solution consisting of previous standard nutritive solution except that nitrogen (N) form was added with either (0.25, 1, 2.5, 5, 10 mM) KNO3 or KNO2. Exudates were collected over 70 minutes periods but that obtained during the first 10 minutes was discarded to avoid contamination by cut tissue. Nitrate, in exudates was colometrically determined on an automatic analyser following diazotation of the nitrite obtained by reduction on a Cd column [19]. The nitrite concentrations are determined in exudates by diazotizing with sulphanilamide and coupled with NED dihydrochloride to form a colored azo-dye that is measured colorimetrically [20]. The concentrations of K, Ca and Mg were determined directly in the different dried organs after ashing at 200 °C in nitroperchloric melange (HNO3/HClO4, 3/1, v/v). After cooling, 25 ml nitric acid solution (1%, v/v) were added to mineralise. Potassium was determined on nitric extract by flame photometry and Mg and Ca by atomic absorption spectrometry (PERKIN-ELMER, analyst 300). For all experiments, each treatment was repeated six times. The least significant differences (LSD) at 5% were used for mean comparison.

2.2.2 Measurements of NO3 and NO2 uptake rate

Intact seedlings were used in all experiments. Net uptake of NO3 and NO2 was measured by ambient depletion [21]. The seedlings were then placed in a controlled environment growth chamber. Uptake was started by placing two series of seedlings in glass recipients containing 250 ml of appropriate solution (the first series containing KNO3 doses ranging from 0.25 at 10 mM and second series containing KNO2 with similar doses than nitrate). The solutions were continuously bubbled with air. Rates of uptake were remained relatively constant during the uptake assay time (1 hour). Concentrations of NO3 and NO2 were periodically analysed in the nutritive solutions, and their levels were immediately recovered in term of every taking (1 hour) by adding appropriate volumes of the stock solutions. After that, the seedlings were pretreated with 0.1 mM NO3− and NO2− for 14 hours and then transferred to the solutions containing 1 mM of these two N-form solutions. Uptake data were expressed on the basis of one gram of fresh weight of roots.

2.3 Histological studies of stem sections

Histological study is based on the realisation and observation of transversal section made at the level of stem (second between-knot) at 10 mM KNO2 and KNO3 on photonic microscope. In the first place, organ fragments were taken to temperature ranging from –15 to –20 °C and cut out 5 μm thickness sections with the help of microtome congelator. Cellular content was obligatory eliminated by sodium hypochloric. Then, these sections were treated with acetic acid before their dip out into carmen iode green substance. The alun Carmen iode coloured cellulosic wall in pink and iode green was fixed on lignin walls.

3 Results

3.1 Changes in ions uptake and translocation

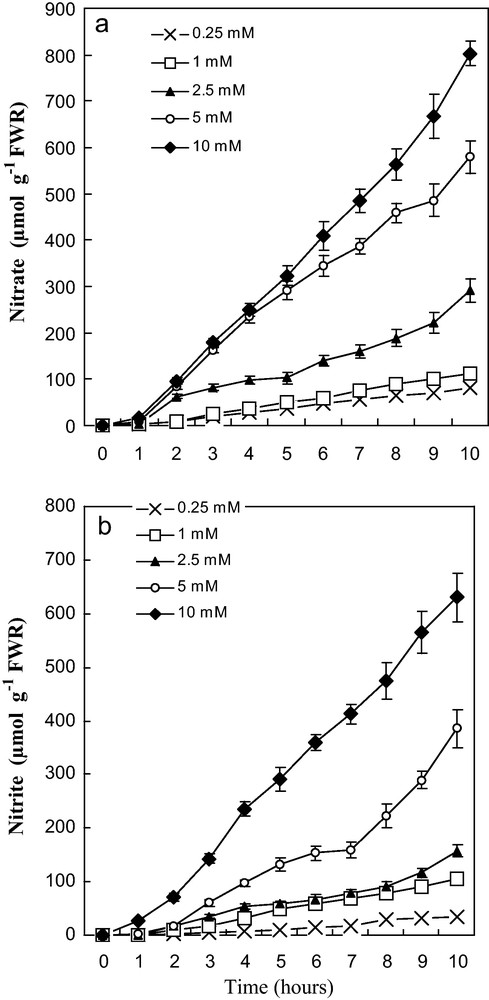

Intact seedlings were used in all experiments. Both NO3 and NO2 uptake systems were not induced by either ambient NO3− or NO2−. Our data showed that nitrogen-deprived plants could not initially take up NO3− when exposed to NO3− solution (Fig. 1a). After a brief lag period of 1 to 2 hours at elevated NO3− doses of nitrate, plants developed the ability to take up NO3−, indicating that NO3− uptake by tomato roots is a carrier-mediated process induced by this ion (Fig. 1a).

Effect of various concentrations of NO3− and NO2− onnitrate uptake (a) and nitrite uptake (b) of tomato seedlings (non-induced) placed in solutions containing different doses of KNO3 and KNO2 (0,25 at 10 mM). R: roots. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). SE is indicated by bars when larger than symbol.

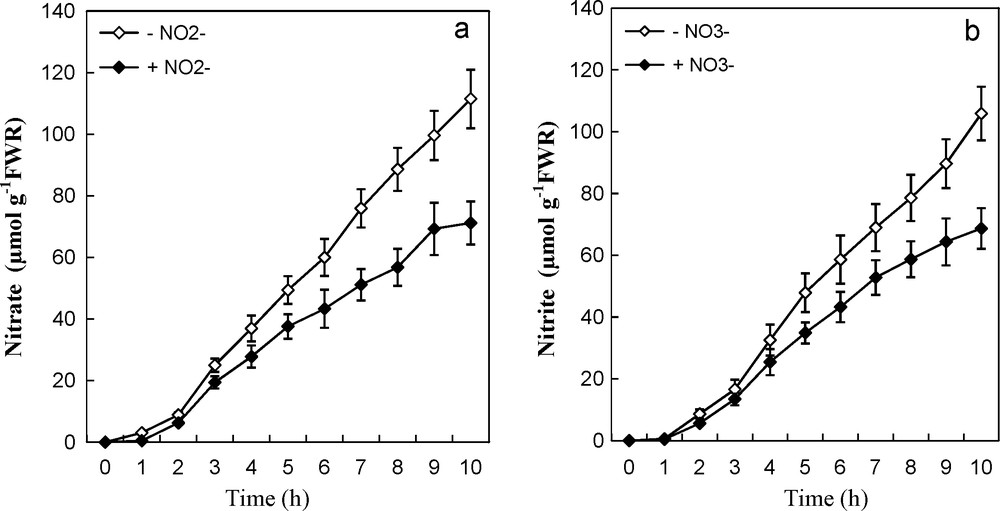

In a similar manner, intact plants were transferred to the same doses of NO2− during 10 hours. Uptake of NO2− also exhibited a brief lag period upon first exposure to external KNO2 solutions, suggesting that NO2− acted as inducer of its uptake systems. Besides, these systems are highly dependent on a continuous supply of this ion (Fig. 1b). This figure showed that uptake proceeded linearly from the beginning, with a typical progress curve of NO2− absorption in a solution containing doses ranging from 0.25 to 10 mM NO2−. Presumably, the uptake of NO3− and NO2− into roots was proportional to the concentration of external N supplied in the non-induction solution and continued at a near constant rate through 10 hours (Fig. 1a and b). Similar uptake rate of NO3− and NO2− occurred at each applied concentration. Addition of NO2− (1 mM) in the uptake medium of NO3−, resulted in an uptake reduction of this ion (Fig. 2a). This was observed especially from fourth hours of absorption and it became more obvious with time; inhibition was about 25 and 35% at 4 and 10 hours respectively. Likewise, the presence of equivalent dose of nitrate in the absorption solution of nitrite (1 mM KNO2) was associated with a decrease in the assimilation of the latter (Fig. 2b). This restriction in absorption of nitrite was about 22 and 36% at 4 and 10 hours, respectively.

Effect of NO3− and NO2− pretreatments on the uptake of NO3− (a) and NO2− (b) by intact tomato plants. Prior to uptake experiments, nitrogen-starved plants were pretreated for 14 hours with 0.1 mM NO3− or NO2−. R: roots. Values are means ± SE (n = 6). SE is indicated by bars when larger than symbol.

The vascular exudates of 7-day old plants treated with increasing doses of KNO3 and KNO2, were analysed in order to assess the effect of NO3− and NO2− on exportation process of NO2−, NO3− and its accompanied cation K+ (Table 1). Obtained data showed that the enriched NO3− medium led to more elevated xylem concentration in NO3− and K+. In fact, increasing external KNO3 concentrations was associated with increasing xylem exudates NO3− concentration from 1.40 to 6.70 and K+ concentration from 1.92 to 5.82. On the other hand, no trace of NO2 ions was detected in KNO3 exudates plant (Table 1). Moreover, our results indicated that accumulations in xylem exudates of these K+ and NO3− ions showed similar patterns under NO2− treatments (Table 1). Nitrate accumulation increased steadily until 5 mM KNO2. Beyond this dose, NO3− was no longer detected in xylem exudates. Just as, xylem concentration of K+ was affected approximately in same manner as NO3− (Table 1). This could be explained either by limitation of radial K+ and NO3− migration through cortical cell roots or by inhibition of their secretion in the xylem. On the other hand, NO2− concentrations showed a moderate elevation with increased KNO2 in the nutritive solution.

Composition of the xylem sap NO3−, NO2− and K+ in the exudate of decapitated plants at different doses and form of N nutrition. Data shown are means of six replicates ± S.E. The least significant differences (LSD) were applied at 0.05 confidence level.

| [NO3−] (mM) | [K+] (mM) | [NO2−] (mM) | ||||

| (mM) | KNO3 | KNO2 | KNO3 | KNO2 | KNO3 | KNO2 |

| 0.25 | 1.43 ± 0.44 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 1.92 ± 0.68 | 1.13 ± 0.21 | ND | 0.43 ± 0.08 |

| 1 | 1.59 ± 0.33 | 0.55 ± 0.05 | 2.54 ± 0.61 | 1.66 ± 0.41 | ND | 1.05 ± 0.25 |

| 2.5 | 2.30 ± 0.68 | 1.63 ± 0.57 | 2.87 ± 0.59 | 1.40 ± 0.30 | ND | 1.93 ± 0.72 |

| 5 | 4.64 ± 1.07 | 3.72 ± 0.42 | 4.91 ± 0.83 | 1.93 ± 0.67 | ND | 2.32 ± 0.42 |

| 10 | 6.66 ± 0.35 | ND | 5.82 ± 1.54 | ND | ND | ND |

The volume flux rate of the exudates was markedly lower in plants grown in NO2− than those grown in NO3− (Table 2). Furthermore, volume flux rates were decreased even at lower concentrations especially in NO2−-fed than in NO3−-fed plants. At 5 mM NO2−, we noticed a perceptible decrease of this parameter by about 60% less than values obtained with 5 mM NO3−. Moreover, plants root became unable to uptake nutrient from medium when treated with 10 mM NO2− (Table 2).

Volume flux and flux rates of NO3−, NO2− and K+ in the exudate of decapitated plants at different doses and form of N nutrition. FWR: fresh weight roots. Data shown are means of six replicates ± S.E. The least significant differences (LSD) were applied at 0.05 confidence level.

| Nitrogen (mM) | 0.25 | 1 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | |

| (ml/h/g/FW R) | ||||||

| KNO3 | 0.61 ±0.01 |

0.43 ±0.03 |

0.56 ±0.04 |

0.65 ±0.07 |

0.84 ±0.01 |

|

| KNO2 | 0.35 ±0.02 |

0.39 ±0.01 |

0.48 ±0.05 |

0.24 ±0.02 |

– | |

| (μmol/h/g/FW R) | ||||||

| KNO3 | NO3− | 2.04 ±0.04 |

4.79 ±0.08 |

7.94 ±0.13 |

11.73 ±0.22 |

29.34 ±0.33 |

| K+ | 3.14 ±0.10 |

1.95 ±0.08 |

3.61 ±0.11 |

7.45 ±0.13 |

13.86 ±0.31 |

|

| KNO2 | NO3− | 1.34 ±0.03 |

3.44 ±0.08 |

5.18 ±0.12 |

4.65 ±0.09 |

– |

| NO2− | 1.98 ±0.02 |

2.5 ±0.06 |

14.18 ±0.23 |

12.56 ±0.13 |

– | |

| K+ | 2.14 ±0.08 |

1.07 ±0.07 |

1.95 ±0.01 |

0.84 ±0.01 |

Likewise, reduction of xylem fluxes with higher doses of NO2− was associated with clear diminution of flux ionic rates. However, solution lacking in nitrite showed some NO3− sap fluxes (Table 2), suggesting a conversion of NO2− to NO3− in extra cellular liquid. The fluxes of NO3− and K+ in the xylem exudates were also significantly reduced by NO2− in comparison with NO3− nutrition (Table 2). However, NO2− flux rates were important especially at 2.5 and 5 mM of KNO2. At 10 mM, NO2− excess altered root structures leading to fluxes obstruction.

Thus, compared with ionic flux, the volumic one represented in Table 1 showed that evolution of these two fluxes was dependent on the nitrogen form of nitrogen introduced in nutritive solution. In fact, we observed an increase of the volume flux rate of the exudates in presence of KNO3 doses gradually accompanied with a marked ionic flux increase of NO3− and K+ (Table 2).

3.2 Changes in nutrients contents

In the second part of this study, we have determined mineral composition of different tomato organs especially K+, Ca2+ and Mg2+ according to the form and concentration of N nutrition. We obtained an increase of K+ content in all organs with N-concentration ranging between 0.25 and 1 mM, but this was more obvious with KNO3 than with KNO2 (Table 3). Under nitrate nutrition, K+ content was unchanged in roots and stems until 1 mM, it increased after that especially in leaves. In both roots and leaves of NO2−-fed plants, we noted a progressive decline in K+ contents from 1 mM treatment. Decreasing K+ contents in stems was recorded at 5 and 10 mM KNO2. At the highest NO2− treatment, this diminution reached 67, 91 and 64% in leaves, stems and roots, respectively (Table 3).

Content of K+, Ca++ and Mg++ (μmol/g FW) in leaves, stems and roots of tomato plants exposed during 10 days to 10 mM KNO3 or KNO2 in culture medium. Data shown are means of six replicates ± S.E. The least significant differences (LSD) were applied at 0.05 confidence level.

| Nitrogen (mM) | ||||||

| K+ | 0.25 | 1 | 2.5 | 5 | 10 | |

| KNO3− | Leaves | 214.30 ± 72.1 | 343.91 ± 85.5 | 374.56 ± 95.3 | 435.72 ± 105.6 | 461.45 ± 104.2 |

| Stems | 77.52 ± 15.9 | 83.41 ± 26.2 | 121.48 ± 42.1 | 123.6 ± 33.3 | 128.41 ± 44.2 | |

| Roots | 275.31 ± 72.2 | 394.21 ± 95.1 | 371.32 ± 74.4 | 433.74 ± 107.2 | 351.65 ± 85.5 | |

| KNO2− | Leaves | 221.35 ± 58.1 | 281.42 ± 58.7 | 233.09 ± 58.1 | 169.32 ± 48.7 | 149.18 ± 48.13 |

| Stems | 74.73 ± 26.8 | 82.89 ± 21.3 | 85.33 ± 18.2 | 72.65 ± 13.2 | 11.2 ± 2.4 | |

| Roots | 281.83 ± 87.3 | 335.15 ± 89.3 | 268.42 ± 72.8 | 243.45 ± 73.5 | 126.22 ± 93.4 | |

| Ca++ | ||||||

| KNO3− | Leaves | 85.40 ± 14.88 | 74.66 ± 10.42 | 75.6 ± 14.3 | 59.14 ± 10.88 | 51.55 ± 8.58 |

| Stems | 7.27 ± 2.2 | 10.63 ± 3.14 | 9.17 ± 1.2 | 11.72 ± 3.2 | 12.21 ± 3.12 | |

| Roots | 13.77 ± 3.9 | 12.99 ± 3.10 | 9.8 ± 2.1 | 26.8 ± 6.22 | 26.28 ± 4.94 | |

| KNO2− | Leaves | 64.45 ± 14.54 | 50.8 ± 11.2 | 50.17 ± 6.65 | 53.12 ± 9.66 | 41.45 ± 7.52 |

| Stems | 5.12 ± 2.47 | 6.88 ± 2.2 | 6.45 ± 1.97 | 4.28 ± 0.98 | 4.26 ± 1.04 | |

| Roots | 14.89 ± 3.52 | 14.51 ± 2.97 | 13.89 ± 4.51 | 21.92 ± 5.89 | 89.82 ± 5.11 | |

| Mg++ | ||||||

| KNO3− | Leaves | 171.52 ± 38.1 | 229.82 ± 42.1 | 230.45 ± 43.2 | 250.25 ± 55.2 | 275.88 ± 56.8 |

| Stems | 37.5 ± 7.9 | 48.75 ± 8.8 | 45.8 ± 8.6 | 49.1 ± 9.2 | 38.1 ± 9.8 | |

| Roots | 76.1 ± 14.1 | 67.69 ± 10.4 | 53.38 ± 11.8 | 114.4 ± 18.1 | 56.77 ± 10.9 | |

| KNO2− | Leaves | 95.22 ± 25.23 | 96.45 ± 22.1 | 111.42 ± 27.4 | 86.36 ± 19.4 | 53.17 ± 12.1 |

| Stems | 31.4 ± 8.84 | 39.37 ± 10.2 | 38.12 ± 9.8 | 27.73 ± 9.7 | 23.18 ± 8.4 | |

| Roots | 50.92 ± 10.2 | 43.21 ± 11.2 | 37.11 ± 8.9 | 68.18 ± 12.2 | 18.4 ± 5.2 |

Concerning calcium, results showed, especially at highest nitrite dose, a strong augmentation of about 70% of this element in roots, against a diminution which seems to affect especially stems (65%) and leaves (19%) (Table 3). Magnesium contents decreased in response to 10 mM NO2− exposure in roots and shoots. We noted a reduction of about 80, 40 and 65% respectively in leaves, stems and roots (Table 3).

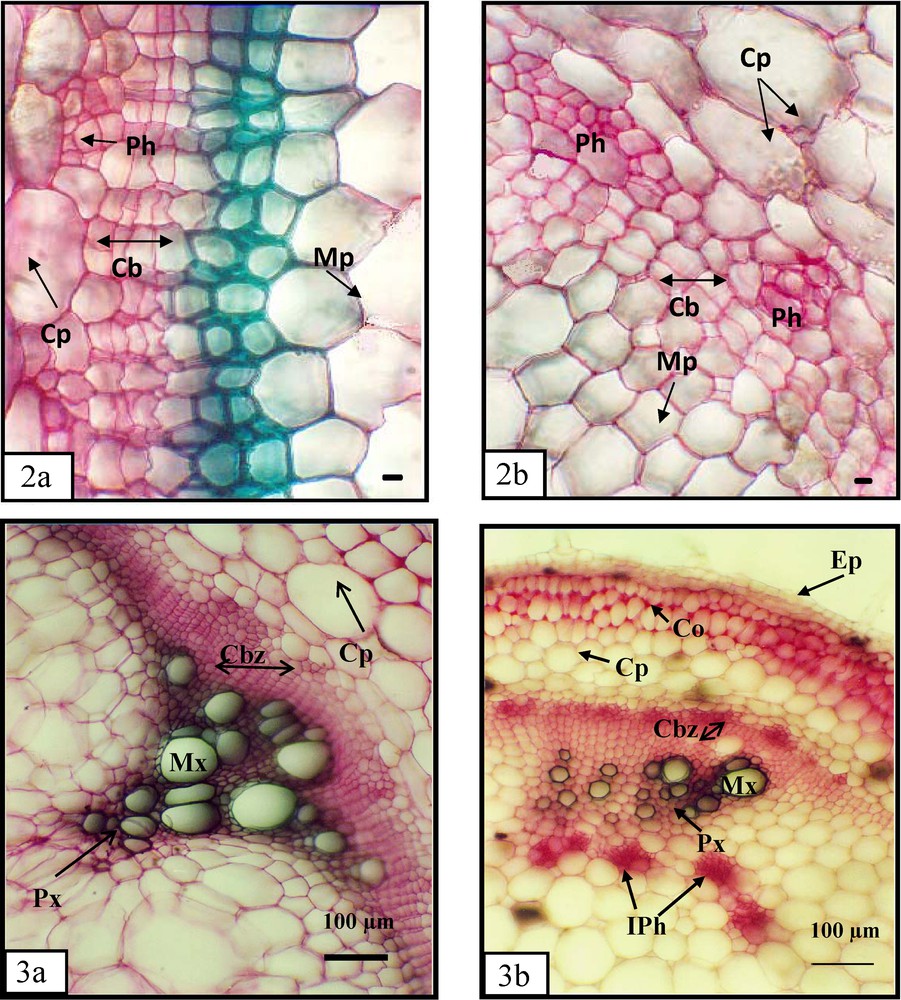

3.3 Structural modifications

Scant information is available concerning effects of N forms on organ anatomy modifications. Tomato stem size was greatly reduced by 10 mM KNO2 (data not shown). The changes of size may be related to the structural arrangements of tissue organs. The anatomy structure of this organ treated during 7 days with 10 mM KNO2 was analysed through transversal second node stalk sections. These plants cultivated for the same period with 10 mM KNO3 were used as control. Our assays showed that stem diameter size was significantly lower in 10 mM NO2−-fed than in 10 mM NO3−-fed plants (Fig. 3a, b), which could be suggested as histological marker of nitrite toxicity. This stem diameter reduction could be explained by diminution of different tissue extents, particularly the size and the number of cellular lines, which constituted these extents.

Cross-section of a transversal stems (second between-knot), of 17 days old Tomato. Areas enclosed in the numbered boxes are enlarged in the corresponding figure. Scale bar = 600 μm. a and b (G X 145). Epiderms (Ep), cortex (Cr), Marrow (Ma), Xylem (Xy), Phloem (Ph), Hair (Ha). a: plants cultivated in 10 mM nitrate (7 days); b: plants cultivated in 10 mM nitrite (7 days). a and b (G X 900). Details stem cortex: epidermis (Ep), cortical parenchyma (Cp), collenchyma (Co), Hypoderm (Hy), Phloem (Ph), and Cambium (Cb). a: plants treated (7 days) with 10 mM nitrite; b: plants treated (7 days) with 10 mM nitrite. a and b (Gr X 1800). Details of the cambial zone: cortical parenchyma (Cp), phloem (Ph), medullar Parenchyma (Mp) and Cambium (Cb). a: plants cultivated in 10 mM nitrate (7 days); b: plants treated (7 days) with 10 mM nitrite. a and b (Gr X 450). Detail of conductors tissues stems: intern Phloem (IPh), Meta-xylem (Mx) and cambial zone (Cbz). a: plants cultivated in 10 mM nitrate (7 days); b: plants treated (7 days) with 10 mM nitrite. Scale bar = 100 μm.

In fact, in the presence of 10 mM of two N-forms, the cortex (Cr) extension of control stem was more important compared with treated one (Fig. 3.1a, b). Moreover, we noted especially with the highest N doses some modifications of form and number lines of collenchymas (Co) tissue cellular. These cellular show cellulosic primary-wall enlargement with 10 mM KNO2 (Fig. 3.1b), indicating that the level of cell-wall synthesis was high. This is less clear in indicator stems cultivated with 10 mM KNO3 (Fig. 3.1a). Furthermore, in this same area of treated stems by highest NO2 concentration, the size of cortical parenchyma cells (Pc) was reduced in comparison to the control ones (Fig. 3.1a, b).

Cambium (Cb) functioning or generating zone libero-ligneous was also dependent in form and dose of nitrogen added in culture medium. These differentiated cambial cells of this second meristem undergo some rapid mitotic division as well from xylem (Xy) side as from the phloem (Ph) one. Cells coming from these divisions are differentiated, in liber from xylem side and in wood from phloem side, they constitute with cambial cells the cambium zone (Z. Cb). This zone situated between these two tissues, constitute more often than not a continuous pachyt (Fig. 3.2a), but it was less differentiated in treated 10 mM KNO2 stems than control (Fig. 3.2a, b). The cambial zone treated with the highest nitrite dose was less developed. In fact, we observed a development of secondary tissue with a second wall essentially formed with lignin substance coloured in green. This structure was lacking in NO2−-fed plant stems, which reflect noxious and inhibitor effect of NO2− dose on growth and maturity of stems (Fig. 3.2a, b).

Besides, our results show that the conductor tissues also emphasized some changes according to the form and dose of exogenous nitrogen (Fig. 3.3a, b). These tissues presented especially at 10 mM NO3− a lot of xylem vascular number (Fig. 3.3a). At the same concentration, these vascular conductors get together in beam emphasizing a remarkable increase of their diameter (Fig. 3.3a). Even though, with 10 mM of KNO2, they appeared less developed and more reduced (Fig. 3.3b).

4 Discussion

Generally, excess of nitrite nutrition alters the physiological mechanisms of the tomato root and shoots and disrupts its morphological organization. The comparative study of increasing KNO3 doses (control) and KNO2 one's (stressed), enable a whole plant assessment of physiological disorders and anatomy alterations.

Nitrite is thought to be a transient intermediate in the nitrate assimilation pathway, being produced from nitrate by NR and then being rapidly reduced to ammonium by nitrite reductase (NiR) [22,23]. Nevertheless nitrite, in contrast to nitrate, is considered a toxic metabolite whose accumulation can have deleterious effects on plant cells [24]. Nitrite does not accumulate in plant cell to nearly great extent due to the rate-limiting activity of nitrate reductase [25]. Nevertheless, nitrite is a particularly interesting regulator molecule since it appears to be taken up by the same transporters for nitrate [21] and able to induce the high affinity transporter's systems (iHATS) as is nitrate itself [26]. These were shown to be due to nitrate contamination in the nitrite solutions or to the inhibition of two of the nitrate-nitrite transport systems [27]. Fig. 1a and b illustrated the pattern of nitrate and nitrite uptake with their varying external concentration. The pattern and uptake reached are relatively similar for these two ions. The existence of an inducible NO2−-uptake system, scarcely studied in higher plants, has only been observed in wheat [28] and barley [29].

Tomato plants were also able to develop a NO2−-uptake system when exposed to NO2−. This indicates that NO3− and NO2− were equally effective in inducing the uptake systems of either ion. We further showed that the induction of both uptake systems occurred after a brief lag period upon first exposure. These resemblances described above could be retained to sustain that these two ions could share a similar carrier-mediated mechanism [30]. Furthermore, Fig. 2a shows the effect of NO2− (1 mM) on NO3− uptake by roots of seedlings in presence of 1 mM KNO3. A similar response has been found for NO2− uptake (Fig. 2b). [21] reported that double reciprocal plots indicated that NO3− and NO2− inhibited the uptake of each other's competitively in both uninduced and induced seedlings. Experiments measuring influx/efflux using nitrite to inhibit nitrate, suggested that distinct uptake systems exist for both ions [30]. Both anions may be transported by different carriers [31], because higher concentration of nitrite leads to ammonium toxicity [32], the increased symptoms may be induced by the accumulation of NH4+ accompanied with the disturbance ions uptake.

Reduction in NO3−-uptake was also closely related to another nitrite effect which alter exudates composition and reduces the mass flow of ions to the roots and their content in all organs. Thus, Tables 1 and 2 showed, in addition to the reduction of exudate volume flux in NO2−-fed plants, a reduction of the translocation and accumulation rates of K+ and NO3− in the xylem exudates. Furthermore, in the present study flux and accumulation rate of K+ and NO3− were increased even in plants supplied with NO3− compared to NO2− (Tables 1 and 2). The results also suggested that the NO3− and K+ concentration of xylem sap could be effectively used to estimate the N status of the soil solution [33]. It is not surprising that increased nitrate influx is associated with enhanced K+ transporter expression because it has been previously documented that stimulated nitrate provision and uptake is associated with increased K+ influx, which has an important and specific role in all living cells and functions as the major charge-balancing cation [34]. Besides, in the present experiments large amounts of NO3− were measured in the xylem exudates of plants supplied with NO2− (Table 1). [35] reported that nitrite in barley leaves is capable of being oxidized to nitrate. In fact, several studies have confirmed the dissolution phenomenon in the extra cellular water to form both HNO2 and HNO3 which then dissociate to form nitrate, nitrite, and protons [36].

In our study, increased doses of nitrite is accompanied with pH decrease in culture solution (data not shown). In fact, the majority of nitrogenous fertilizers used are physiologically acidic. Particulary, nitrite (KNO2) may also be a significant stress factor in acid environment [37] and it is necessary to emphasize that soil pH affects the uptake of various nutrients by the roots. Thus, a decrease of the pH of the external solution leads to increased inhibitory effects of nitrite on both ion uptake and growth of the seedlings. In fact, ionic composition analysis of plants treated with NO2− emphasized a severe K+ deficiency in all tomato organs (Table 3). Further studies showed the effect of K+ deficiency on the diurnal changes in stem diameters of tomato plants [38]. Thus, tomato stem size was greatly reduced by 10 mM NO2− (Fig. 3a, b); as a consequence, the translocation of nutrients to the shoots was also impaired. Moreover, nitrogen and K stress altered not only the xylem sap composition, but it also significantly reduced nitrate (NO3−), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg) contents [33]. To perform these varied and multiple roles, K uptake and utilization often interact with the availability and uptake of other nutrients. Fertilization using higher than necessary doses of potassium leads to the occurrence of the characteristic symptoms of magnesium deficiency on aerial organs [33]. Potassium is a strongly antagonistic element towards magnesium and, therefore, it blocks both magnesium uptake and its transport within the plant. Over-fertilization with potassium is very dangerous for plants because it stimulates the symptoms of magnesium and calcium deficiencies.

In our studies, the content of Ca2+ were greater in roots of NO2−-fed plants than in NO3−-fed ones. The little effect on roots could be associated with the superficial localisation of the bivalent cation in this organ [39]. But, stems and leaves Ca2+ contents showed a decrease with this stress (Table 3). It is possible that a decrease in endogenous concentrations of Ca2+ with 10 mM KNO2 increased cellulose incorporation in collenchyma stem cells (Fig. 3.1b). These results suggest that the earlier reported inhibition of cell wall extension, induced by high NO2− concentrations, could be due to a stiffening of the primary collenchyma cell wall, resulting from changes in the wall synthesis pattern (Fig. 3.1a, b).

Other studies have demonstrated that increasing N-availability (ground and air) causes a cambium disorganization, which leads to nutritional imbalance [40]. It was also noticed that treated plants exhibited a lack of secondary lignin wall cells structure which indicates a delay in maturity of this tomato stalk associated with a higher nitrite doses, comparable to a control organ (Fig. 3.2a, b). In fact, lignification was almost totally suppressed at low concentration of Ca2+ [41]. Besides, [42] found that concentration of NO2− and the degree of its toxicity were intimately related to the availability of magnesium at root medium in tomato plants. Our results showed that, in comparison to nitrate treatment, the higher doses of nitrite negatively affected magnesium content in all different organs of tomato plants (Table 3). In addition, we recorded a reduction of the number and size of vascular tissue (Xylem I and phloem I) (Fig. 3.3a, b). As well, [43] noted that disturbances first occurred in the cambium, then in the phloem, and finally in the xylem. Magnesium plays an important role in the phloem loading process [44]. Thus, a severe lack of local Mg might cause a large decrease in osmotic pressure in the sieve cells, which consequently collapse. In addition, in saplings grown on nitrogen-enriched soil the number of tracheids and the number of latewood tracheids decreased [45].

Finally, the overall results confirm that nitrite exhibits harmful effects on tomato plant. The growth characteristics of the reduced lignin plants were significantly impaired, resulting in smaller stems and reduced plant organs biomass when compared to control plants. The severe inhibition of cell wall lignification produced stems with a collapsed xylem, resulting in compromised vascular integrity, and displayed reduced cation contents and a greater susceptibility to wall failure and cavitation. This examination presents the complexity of nutrient use efficiency and supports the idea that the integration of the numerous data coming from structural studies, ion uptake and quantitative mineral contents into explanatory models of whole-plant behavior will be promising. As a conclusion, it should be noted that this toxic form of nitrogen that increases structural disorganization leads to nutritional discrepancy.

Disclosure of interest

The authors have not supplied their declaration of conflict of interest.