1 Introduction

The order Phasmatodea constitutes a morphologically distinctive group of winged insects [1,2]. More commonly known as stick and leaf insects, members of Phasmatodea are famous for their use of plant-specific crypsis as a defence mechanism aimed to reduce the risk of visual detection by predators [3,4]. In such an adaptive scenario, these insects display some of the most extreme cases of evolutionary convergences in morphology and behaviour documented among animals [5].

Molecular phylogenetic analyses of extant phasmatodeans revealed a basal split into two groups: one branch including the relictual genus Timema, the other comprising all remaining lineages of the order in the clade Euphasmatodea [6,7]. Lower limits for this divergence within the order are reported around the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary, between 95 and 150 million years ago [5,8]. Over this evolutionary time Timema and Euphasmatodea have acquired significant morphological differences [1]. Timema, with 21 Neartic species [9], has been morphologically characterized in various character systems [10–15]. In comparison the morphology of the diverse Euphasmatodea is less well documented, as accurate studies of key systematic characters are available for only a few taxa among the ∼3000 species known worldwide. Particular attention was paid to the genus Agathemera [12,16,17], that possibly represents the sister group to the rest of the Euphasmatodea grouped in the clade Neophasmatidae by Bradler [18]. Valuable information on euphasmatodean morphology have been provided for the head [17,19–22], the pterothorax [23,24], the locomotory attachment system [13,25–27], the muscle and nerve arrangement of mid-abdominal segments [12], the eggshell [28–34], and the male genitalia of the genus Oxyartes [35]. Recently, a noteworthy contribution in this field has been made by Bradler [18], who reviewed 92 morphological characters developing a matrix to analyze the phylogenetic relationships between 89 selected species.

Hermarchus leytensis Zompro, 1997 is a distinctive but poorly known species of the Philippine stick insect fauna. To date it has been documented from only a dozen female specimens found in the southeastern part of the archipelago, specifically in the two islands Leyte and Mindanao [36,37]. H. leytensis is believed to belong to the Stephanacridini sensu Hennemann and Conle [38], a rather small euphasmatodean subgroup for which only meagre morphological information is available. Nevertheless, Stephanacridini are particularly interesting in phasmatodean systematics because they are considered to form the plesiomorphic sister group to a large clade of Australasian stick insects referred to as Lanceocercata [39,40]. The present study investigates the external morphology of the newly discovered male of H. leytensis through direct gross morphological observations, coupled with ultrastructural imaging using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). It is the intent of this study to augment our knowledge about some major features of euphasmatodean exoskeletal morphology, particularly those relating to characters of the head, locomotory attachment devices, and terminalia. The results are discussed with respect to phasmatodean phylogeny, and the placement of H. leytensis within Stephanacridini. This article is also a contribution to a project aimed at studying the systematics of Philippine stick and leaf insects [41–44].

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Source and culture of specimens

Several eggs of H. leytensis were obtained for culture purposes form females found in the surroundings of Mount Apo, Mindanao, Philippines. Four males were reared to adulthood in ventilated cages at a temperature of 23–25 °C. Hypericum sp. was used as alternative food plant. The availability of laboratory-reared males allowed the description of chromatic characters and the unequivocal identification of additional dried preserved males. A total of seven adult males were studied: one male, Mindanao, Mt. Apo, 1300 m, 27.III–10.IV.2006, leg. R. Cabale; four males reared by M. Gottardo 2007; one male, Mindanao, Surigao del Sur, Tandag, 12–20.IV.2008, leg. R. Cabale (preserved in the personal collection of Marco Gottardo, Rovigo, Italy); one male, Mindanao, South Cotabato, Mt. Busa, III.2007, leg. R. Cabale (preserved in the personal collection of Frank H. Hennemann, Freinsheim, Germany).

2.2 Morphological and ultrastructural observations

The examination of the gross external morphology was carried out using a Zeiss Stemi DV4 stereo light microscope. Macro-photographs of the habitus and of various body parts were taken with a Nikon D50 digital camera. For SEM observations, the dried specimens were put in a humid chamber to restore flexibility through a slight rehydration, and then samples of mouthparts, tarsi, and of the terminalia were removed from the body. After rinsing several times in distilled water, the samples were dehydrated in a graded Ethanol series and critical-point dried in a Balzers CPD 030 apparatus. The material was mounted on aluminium stubs with the conducting carbon adhesives in between, gold-coated in a Balzers MED 010 sputtering device, and observed with a Philips XL20 scanning electron microscope operating at an accelerating voltage of 10 kV.

3 Results

The male of H. leytensis is characterized by a slender stick-like habitus and the presence of brachypterous wings (Fig. 1). The integument of the body appears smooth and slightly glossy. A full set of measurements is given in Table 1.

(Colour online). Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). Habitus of a live specimen.

Morphometric data for males of Hermarchus leytensis from Mindanao Island, Philippines.

| Length (mm) | Range | M ± SD | n |

| Body | 72.3–93.9 | 86.3 ± 7.70 | 6 |

| Antenna | 55.3–66.0 | 60.3 ± 3.97 | 5 |

| Head | 3.5–4.1 | 3.9 ± 0.21 | 6 |

| Pronotum | 2.6–3.1 | 2.9 ± 0.17 | 6 |

| Mesonotum | 17.8–24.0 | 21.6 ± 2.23 | 6 |

| Metanotum | 3.9–4.5 | 4.2 ± 0.23 | 5 |

| Median segment | 6.9–8.6 | 7.9 ± 0.75 | 5 |

| Tegmina | 4.4–5.1 | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 5 |

| Hind wing | 23.1–27.3 | 25.1 ± 1.35 | 6 |

| Cercus | 1.7–1.9 | 1.8 ± 0.08 | 4 |

| Fore femur | 27.8–32.8 | 30.9 ± 2.05 | 6 |

| Fore tibia | 32.0–39.5 | 36.1 ± 2.95 | 6 |

| Fore tarsus | 10.0–13.0 | 12.2 ± 1.56 | 5 |

| Mid femur | 20.4–26.7 | 24.3 ± 2.13 | 6 |

| Mid tibia | 19.8–28.1 | 24.6 ± 2.84 | 6 |

| Mid tarsus | 8.5–11.3 | 10.0 ± 1.03 | 5 |

| Hind femur | 24.0–31.9 | 28.8 ± 3.39 | 6 |

| Hind tibia | 28.4–35.5 | 32.7 ± 2.48 | 6 |

| Hind tarsus | 10.3–13.4 | 12.0 ± 1.20 | 5 |

3.1 Chromatic features

The head is whitish, with yellowish compound eyes and brown antennae (Fig. 2). The prothorax is pale green, while the meso- and metathorax appear more bright green (Figs. 2 and 4). The tegmina is mid-brown, with a pale brown venation and whitish costal region. The hind wing exhibits a longitudinally striped coloration pattern on the costal region: longitudinal veins are whitish; the areas behind them and cross-veins are dark brown (Figs. 1 and 4A–C). The anal region is uniformly translucent pale brown (Fig. 4A and C). The fore femur is reddish brown with a dark bluish green base (Fig. 1). Mid and hind femora are olive-green with dark brown or black distal ends (Fig. 1). Tibiae show alternate pale brown and dark brown or black bands (Fig. 1). The basic colour of the abdomen is bright green (Fig. 1). The posterior end of terga II–VIII is black (Figs. 1 and 6B). Ventrally, the boundary area between adjacent sterna II–VIII is black with a transversal yellowish brown stripe in the middle (Fig. 6C).

(Colour online). Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). Macrophotography of the head and prothorax. A. Dorsal view. B. Lateral view. C. Frontal view; note the swollen lateral region of the frons with a convexity ventrad the antennal base (asterisks), and the presence of a slightly sclerotized area in the anterolateral region of the antennal field (arrow). D. Ventral view. Apg: aperture of the pronotal gland; Af: antennal field; Bs1: prothoracic basisternum; Ce: compound eye; Cs: coronal suture; Cv: cervix; Cx: coxa; Fla: flagellomere 1; Fs: frontal suture; Ge: gena; Gl: glossa; Lb: labrum; Me: mentum; Md: mandible; MsTh: mesothorax; Pd: pedicellus; Pgl: paraglossa; Plb: labial palpus; Pmx: maxillary palpus; PrNo: pronotum; Sc: scapus; Sg: subgena; Sgr: subgenal ridge; Tr: trochanter. Arrowheads indicate the clypeus.

(Colour online). Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). Macrophotography of the meso- and metathorax. A. Dorsal view, preserved specimen with unfolded wings. B. Dorsal view, specimen with folded wings. C. Ventral view, preserved specimen with unfolded wings. Bs2–Bs3: meso- and metathoracic basisterna; Cx: coxa; Epm: epimeron; Eps: episternum; Fu2–Fu3: meso- and metathoracic furcae; Hw: hind wing; MsNo: mesonotum; Pn: postnotum; Prs: prescutum; Prx: precoxale; Ra: Radius; Sc: scutum; Scl: scutellum; ScP: posterior subcosta; S2: second abdominal sternum; Tg: tegmina; T1: first abdominal tergum; WmA: anterior margin of the hind wing. In A and B, the arrowheads indicate the shoulder pads of the tegminae. In C, the arrows indicate the median longitudinal carina of meso- and metathoracic basisterna.

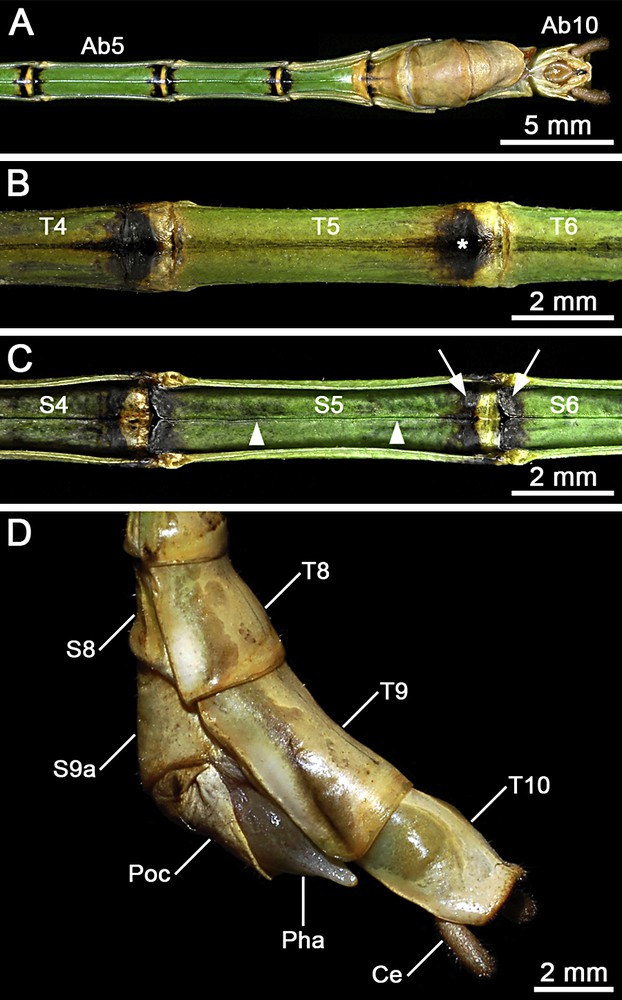

(Colour online). Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). Macrophotography of the abdomen. A. Ventral view from segment V (Ab5) to segment X (Ab10). B. Detailed view of terga IV–VI (T4–T6). Note the characteristic black spot on the posterior end of the tergum (asterisk). C. Detailed view of sterna IV–VI (S4–S6). Note the longitudinal median keel (arrowheads), and the colouration of the boundary area between adjacent sterna with a yellowish brown stripe bordered in black (arrows). D. Details of terminalia in lateral view showing abdominal terga 8–10 (T8–T10), the eighth abdominal sternum (S8), the ninth abdominal sternum divided into an anterior (S9a) and a posterior (Poc) sternite, the prominent phallus (Pha), and the cylindrical cercus (Ce).

3.2 The morphology of the head and mouthparts

The head capsule is prognathous, longer than wide, with the sides slightly narrowing towards the base (Fig. 2A). The gena is somewhat shorter than the diameter of the compound eye (Fig. 2B). The subgena and the subgenal ridge are well developed (Fig. 2B). The dorsal region has a moderately globose vertex with a very faint coronal suture (Fig. 2A). The compound eye is large, circular in shape, and protrudes from the capsule slightly more than hemispherically (Fig. 2A–D). A semicircular mound-like elevation is present between the compound eyes (Fig. 2A and B). Ocelli are lacking. The frontal sutures form an impressed groove in the narrow interantennal space (Fig. 2A and C). The frons is swollen laterally, with a distinct convexity ventrad the antennal base (Fig. 2C). The epistomal ridge is distinct. The clypeus is translucent, and appears bean-shaped with a medially concave anterior margin (Fig. 2C). The labrum is strongly notched anteromedially, with triangularly rounded lateral margins (Fig. 2C and D). The antenna is filiform, almost twice as long as the fore femur (Fig. 1). It is inserted into a large drop-shaped antennal field (the antennal articulatory area) (Fig. 2A). The outer margin of the antennal field meets the base of the front half of the compound eye, without a distinct space separating the two structures (Fig. 2A). A slightly darker and sclerotized area is present in the anterolateral region of the antennal field, but an antennifer is absent (Fig. 2C). The scape is longer than wide and increasingly thickened from base to apex (Fig. 2B). The pedicel is about half the length of the scape and oval in cross-section (Fig. 2C). The first flagellomere is more than twice as long as the pedicel (Fig. 2C).

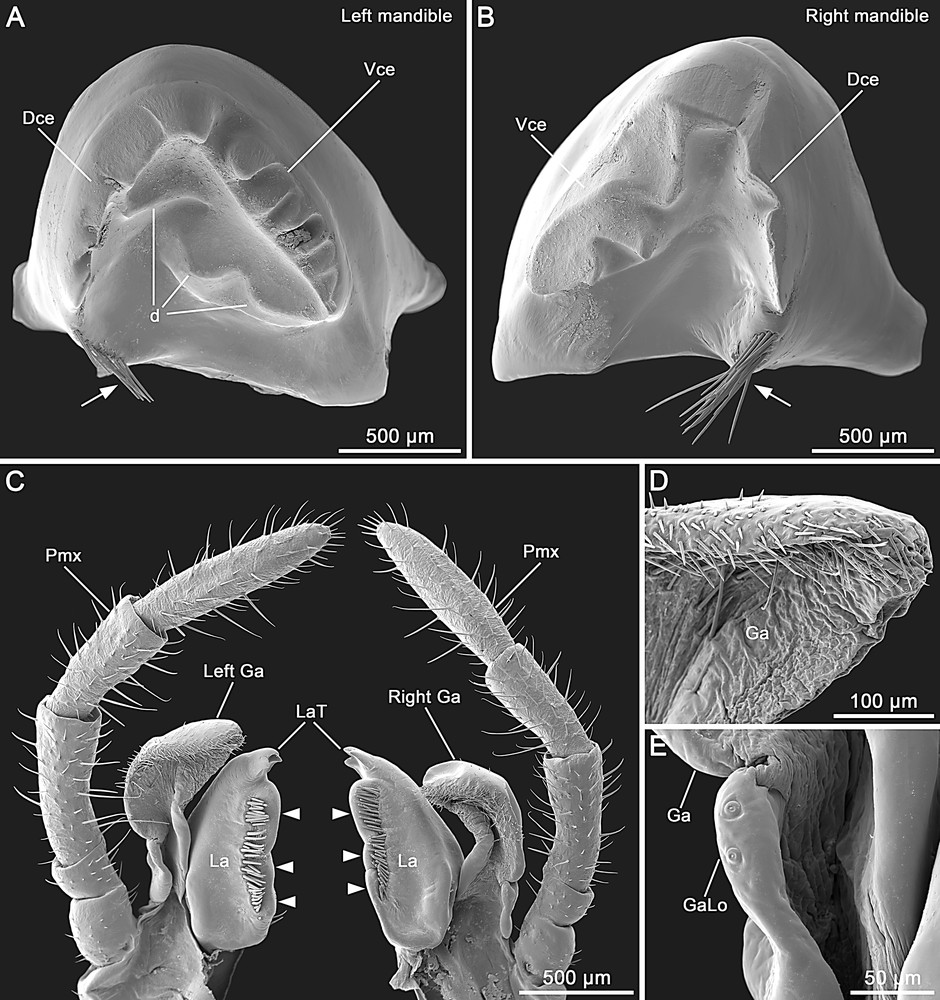

Mandibles are characterized by a dentate dorsal cutting edge (Fig. 3A and B). A tuft of setae is present at the base of the dorsal margin. The ventral cutting edge of the left mandible has a row of 6–7 teeth (Fig. 3A), while in the right mandible this edge has only three larger teeth (Fig. 3B). The concave mesal surface of the left mandible is also equipped with three distinct protuberances (Fig. 3A).

Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). SEM of mouthparts. A and B. Left and right mandibles. Note the teeth on both dorsal (Dce) and ventral (Vce) cutting edges, the three large protuberances on the left mandible (d) and the setation at the base of the dorsal margin (arrows). C. Left and right maxilla in lateral view. Note that the right galea (Right Ga) is slightly smaller than the left one (Left Ga). The lacinia (La) has three lateral membranous outgrowths (arrowheads) and three distal teeth (LaT). Pmx, maxillary palpus. D. Distal portion of the galea (Ga) showing the absence of an area with medially-directed trichomes. E. Detailed view of the small galealobulus (GaLo) at the base of the galea (Ga).

The maxilla has the cardo and stipes separated by a distinct cardostipal suture. The pentamerous palpus has rather cylindrical palpomeres (Fig. 2B–D). The basal two palpomeres are very short, with the palpomere II shorter than I; palpomere III is slightly longer than IV; palpomere V is longer than III (Fig. 3C). The galea has a semimembranous appearance. The right galea is slightly smaller than the left one (Fig. 3C). The outer margin of the galea is strongly setose and lacks a distal apical area of medially-directed trichomes (Fig. 3C and D). The galealobulus is small (Fig. 3E). The mesal side of the lacinia is equipped with a row of enlarged bristles flanking three prominent bearing-like protuberances (Fig. 3C). Distally, the lacinia exhibits three apical teeth (Fig. 3C).

The labium has the prementum slightly shorter than the mentum, both with a distinct median incision (Fig. 2D). The submentum is well developed (data not shown). The trimerous palpus has the palpomeres very moderately flattened dorso-ventrally (Fig. 2B–D). The glossae are sharp-pointed distally (Fig. 2D). The paraglossae are curved, twice as long as the glossae, and anteriorly they reach half length of the labrum (Fig. 2B–D). A gula is present on the ventral side of the head (data not shown).

3.3 Morphological observations on the thorax

The prothorax is longer than wide and slightly narrower and shorter than the head (Fig. 2A). The pronotum has a slight transversal sulcus on the anterior third (Fig. 2A). The anterolateral corners of the pronotum exhibit well-developed openings of the pronotal exocrine glands (Fig. 2A and B). The posterior margin of the pronotum is rounded (Fig. 2A). The coxopleurite is rectangular in outline (Fig. 2B). The basisternum is trapezoidal with a narrow longitudinal median furrow (Fig. 2D). The furca is reduced.

The mesothorax is 6.8–7.8 times the length of the prothorax, and widens slightly posteriorly (Figs. 1 and 4). In the mesonotum, the scutum and scutellum are smooth and rather uniform in width (Fig. 4A and B). The episternum is as long as the scutum and it regularly widens towards the posterior end (Fig. 4C). The epimeron is small and narrow (Fig. 4A). The pleural suture is almost indistinct. The basisternum is barely tectiform, with a distinct median longitudinal carina (Fig. 4C). The precoxale is broadly rounded. The furcasternum is short with a clearly demarcated furca (Fig. 4C).

The metathorax is about one-third the length of the mesothorax. The metanotum is composed of a triangular prescutum, a short scutum + scutellum, and a postnotum fused to the first abdominal tergum (Fig. 4A). The metathoracic pleural region is similar to that of the mesothorax. The metathoracic sternum is fused to the first abdominal sternum (Fig. 4C).

3.4 Morphological observations on the wings

The tegmina is short and slender (Fig. 4A–C), with a small shoulder pad on its posterior half (Fig. 4A). It has a straight hind margin that covers the articulation of the hind wing (Fig. 4A and B).

The hind wing slightly extends over the third abdominal segment (Fig. 1). The anterior margin and bends laterally at the level of the subcosta (Fig. 4A and C). A radius is recognizable just behind the subcosta. Close to the hind wing base, a radial sector branches off from the radius (Fig. 4A).

3.5 The morphology of the legs and attachment devices

The legs are very slender and elongated, with the hind legs strongly extending beyond the tenth abdominal segment (Fig. 1). Coxae are unarmed and trochanters are small (Fig. 2D). Femora are trapezoidal in cross-section and feature five carinae. The fore femur is compressed and slightly incurved at the head level (Fig. 1). The dorso- and ventro-anterior carinae of the fore femur feature 21–25 minute spines. The dorso- and ventro-posterior carinae have 12–20 very small spine-like serrations. The mid and hind femora show 8–17 minute spines on their dorsal carinae, and 14–28 small spine-like serrations on the ventro-anterior and ventro-posterior carinae. All femora are armed with 9–11 very small spines on the medio-ventral carina.

Tibiae are almost triangular in cross-section. In the fore tibia the carinae are strongly setose, and small spine-like serrations are present only on the ventro-posterior carina. The mid and hind tibiae have the medio-ventral carina with a small proximal lobe; all five carinae are setose and armed with numerous small spines.

The five-segmented tarsus is approximately one-third the length of the corresponding tibia (Fig. 1). The basitarsus is distinctly longer than the combined length of tarsomeres II–V. Tarsomeres II–IV are progressively shorter. The tarsomere V (or pretarsus) is almost as long as tarsomere II, and regularly widens from base to apex (Fig. 5A). Tarsomeres I–III lack spines on the carinae, and feature a very moderately developed dorsal lobe (Fig. 5A). The ventral side of tarsomeres I–IV is equipped with a distal double-pad euplantula (Fig. 3A), consisting of two small drop-shaped attachment pads (Fig. 5B and C). The cuticular surface of these attachment pads is smooth (Fig. 5D), and at high magnification shows faint irregular microgrooves (Fig. 5D, inset). The ventral side of the pretarsus has a narrow longitudinal medial field without setation (Fig. 5B). The unguitractor plate is well developed. The arolium is rounded and broad. Pretarsal claws are symmetrical and simple (Fig. 5B).

Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). Structure of tarsal attachment devices. A. Schematic drawings of the fore tarsus in lateral and ventral view. Tarsomeres I–IV (Ta1–Ta4) are equipped with a small euplanta at their distal end (arrows). The pretarsus (Ta5) has an arolium (Ar) and two pretarsal claws (Un). B–D. SEM showing the details of the attachment pad structure. B. The pretarsus (Ta5) observed in ventral view lacks a distinct euplantula, and displays a well-developed unguitractor plate (arrowheads), a large rounded arolium (Ar), and two equally sized pretarsal claws (Un). C. On tarsomeres I–IV each euplantla consists of two attachment pads (Eu) separated from one another by a median space of non-membranous cuticle (asterisk). D. A higher magnification of an attachment pad (Eu) shows the smooth euplantular surface characterized by an irregular pattern of microgrooves and by scattered single pore glandular openings (inset, scale bar = 5 μm).

3.6 The morphology of the abdomen and terminalia

The first tergum (or median segment) is approximately twice as long as the metanotum (Fig. 4A). Abdominal terga II–V increase moderately in length. Terga VI–VIII are progressively shorter. The tergum IX is slightly more than 1.5 times the length of tergum VIII (Fig. 6D). The abdomen is of uniform width from segment II–VI. Sterna II–VII feature a longitudinal median keel (Fig. 6A, C). In the postabdomen, terga VII–VIII widen progressively, whilst terga IX–X narrow (Fig. 6D). The tergum X (or anal segment) is shorter than tergum IX, and appears distinctly tectiform with a clasper-like hind margin (Fig. 6D). Each of the two claspers is equipped with ∼70 ventral tooth-like projections pointing anteriorly (Fig. 7A and B). These teeth are strongly sclerotized and exhibit a sharply rounded apex (Fig. 7C). The paired paraprocts are well developed (Fig. 7A and B). The epiproct is small (Fig. 7A and B), almost W-shaped with a dorsal median carina. The cercus is about 0.6 times the length of tergum X (Fig. 6D). It is rounded in cross-section (Fig. 7A) and moderately incurved in the centre (Fig. 7B). The sternum IX has a transverse furrow at about half of its length, and the poculum exhibits a small notch medioposteriorly (Fig. 6D). A phallic organ distinctly protrudes from the sternum IX (Fig. 6D). The well-developed vomer is symmetrical (Fig. 6A and Fig. 7A and B). Its posterior third narrows to form a straight spike covered with minute spinescent outgrowths (Fig. 7D).

Male of Hermarchus leytensis (Phasmatodea). SEM of the tenth abdominal segment. Ventral (A) and ventro-caudal (B) views show the symmetrical vomer (Vo), the pair of paraprocts (Pa), the cylindrical cerci (Ce) and the small epiproct (arrowhead). The tenth tergum (T10) has a clasper-yshaped hind margin (Cl) equipped with ∼70 minute tooth-like projections on each thorn pad. C. Details of the tooth-like projections located on the ventral side of the claspers. D. Higher magnification the pointed posterior end of the vomer (Vo) showing the dense coverage of minute spinescent outgrowths; Pa = paraprocts.

4 Discussion

4.1 Comparative aspects of the external morphology

4.1.1 Chromatic features

Stick insects are usually characterized by highly cryptic colour-pattern morphs [45], whereas the male of H. leytensis exhibits a particular colouration mainly for the distinctive dark-banded legs and brown and white longitudinal strips on the costal region of the hind wings. Considering the potential closest relationships with other Stephanacridini, it is interesting to note that these chromatic features are also found in the male of Macrophasma biroi from New Guinea [46], and might represent synapomorphies of these two species. Also the colouration of the abdominal sterna appears quite distinctive and not reported in the males of other Stephanacridini [46,47].

4.1.2 Head and mouthparts

Features of the external head morphology of the Phasmatodea has been documented in a small number of species (e.g. Timema cristinae [11], Agathemera crassa and Megacrania sp. [17], Phryganistria virgea [19], Carausius morosus [20,21], and Phyllium siccifolium [22]). Interesting traits observed in H. leytenisis include the laterally swollen frons with a convex area ventrad the antennal base, and the medially notched labrum. These character states are possessed by other stick insects including Timema, and they are considered important autapomorphies of the Phasmatodea [18,22]. A further aspect that deserves discussion concerns the presence/absence of an antennifer. Indeed, we observed a slightly sclerotized anterolateral area within the antennal field of H. leytensis, but as this does not form an articulation with the scapal base it should not be referred to as antennifer. The finding is consistent with previous studies that reported the reduction of the antennifer as being autapomorphic for Euphasmatodea [18,22], while this structure is still present in Timema [11] where it represents a plesiomorphic condition. Mandibles of H. leytensis are characterized by the reduction of the incisivi, an autapomorphy uniting members of the clade Neophasmatidae [22]. Interestingly, details of mandibular structure differ among neophasmatid taxa. For example, H. leytensis exhibits a dentate dorsal cutting edge (in Phyllium: smooth) and three tooth-like protuberances on the mesal surface of the left mandible (in Phyllium: one) [22]. We have examined the maxillae of two males of H. leytensis and in both specimens the right galea was smaller than the left one, in one case also with strongly reduced setation (data not shown). A difference in size and shape between the galeae has not been reported in previous studies of phasmatodean maxillae [18,22,26,48] and might represent an interesting apomorphic feature. The galea appears distinctive also for the lack of an apical field of trichomes. This specialized region is present in the galea of basal phasmatodean lineages such as Timema and Agathemera [17,18], and conceivably its absence in H. leytensis may be an apomorphic condition. The small galealobulus of H. leytensis represents a well-known autapomorphic character of the Euphasmatodea [18,22]. The lacinia of H. leytensis is characteristic for the lacinial setae not protruding over the mesal margin, which consists of three bearing-like protuberances. This is a very unusual condition not reported in other phasmatodeans [11,18,22,26] or even in polyneopteran insects, where typically these setae protrudes from the mesal margin of the lacinia [17,48–50]. The three apical teeth represent another apomorphic ground-plan feature of the Euphasmatodea [18,22].

4.1.3 Thorax

H. leytensis exhibits well-developed openings of the pronotal exocrine glads, constituting an autapomorphic feature of the Phasmatodea [11,18,51]. In various species these glands have been reported to release defensive substances when the insect is under threat of predation [52,53], but in H. leytensis we have not observed this behaviour. The thorax of H. leytensis shows two autapomorphies of the Euphasmatodea: the reduction of the prothoracic furca [1,11], and the fusion of the metathoracic tergum with the first abdominal tergum [11,12,18]. The distinct elongation of the meso- and metathorax is typical of Neophasmatidae [18].

4.1.4 Wings

The male of H. leytensis expresses a brachypterous condition, whereas the female is completely apterous [36,37]. Within Stephanacridini, males of Hermarchus, Macrophasma, and Stephanacris usually have well-developed hind wings [46,54], while varying degrees of wing reduction occur in Nesiophasma, Phasmotaenia, and Sadyattes [47,55]. It is interesting to note that the tegminae of H. leytensis are unusually small and slender compared to those of other males of Stephanacridini. Even though the tegminae of this species are relatively reduced, they exhibit the characteristic ‘shoulder pads’ found in winged Neophasmatidae [18] and also in fossil stem-phasmatodeans [56].

4.1.5 Legs and attachment devices

The basally curved and compressed fore femora observed in H. leytensis represent an apomorphy of the Euphasmatodea [18,45] and this condition is present in all members of Stephanacridini [46,47]. H. leytensis has a strongly elongated basitarsus, which is distinctive of the majority of the Neophasmatidae [18]. Features of attachment devices have been described in Timema and in very few taxa of Neophasmatidae (information on the euplantulae of Agathemera are not available yet). The euplantula found on tarsomeres I–IV of Timema is a single membranous pad with an indistinct median longitudinal furrow [11,13]. A similar organization has been reported in different stick insects, where the longitudinal furrow may be present (e.g. Neohirasea [13]) or absent (e.g. Aretaon, Dallaiphasma, and Conlephasma [13,25,26]). Instead, in H. leytensis each euplantula is actually divided into two separated membranous pads. This distinctive pattern, likely apomorphic compared to the single-pad euplantula, is known to occur in some members of the clade Schizodecema (i.e. Carausius morosus and Medauroidea extradentata [27]). Also the absence of a nubby microsculpture on the surface of the euplantulae (usually present in Phasmatodea) is a possible apomorphic character state of the attachment devices of H. leytensis (for a fuller discussion on this topic, see Gottardo [25]).

4.1.6 Abdomen and terminalia

H. leytensis has a longitudinal median keel on the abdominal sterna. Within Stephanacridini this character is known to occur also in the genus Phasmotaenia [47], and may represent a feature of potential taxonomic interest. In the ground-plan of Phasmatodea the male terminalia are characterized by the presence of a subanal sclerite used to grasp the female during copulation, termed the vomer, and a simple hind margin of the tenth abdominal segment [18]. The vomer observed in H. leytensis is an apparently plesiomorphic feature of the teminalia, and according to Hennemann and Conle [38] this grasping organ was found to be constantly present in Stephanacridini. In H. leytensis the hind margin of the tenth abdominal segment exhibits some features of a clasper apparatus (e.g. tectiform shape and two strongly sclerotized ventral plates equipped with numerous teeth or thorn pads). However, these claspers appear rather simple in structure as they do not show the tergal division into distinct hemitergites that is found in males of certain euphasmatodean lineages (e.g., Clitumninae and Lonchodinae) [18,38]. In phasmatodean systematics, the analysis of the male terminalia has proved to be most useful when some fine details are taken into consideration [10,18,57]. In the context of Stephanacridini, detailed characterizations of male terminalia are available for only two species: M. biroi [18] and Hermarchus pythonius [38]. An interesting difference is that H. leytensis has a symmetrical type of vomer ending with an evenly straight distal spike, while in the two species mentioned above the vomer is asymmetric and forms a hook curved to the right. H. leytensis share with other Stephanacridini the stout general conformation of the claspers. However, significant differences are found when details are compared. H. leytensis displays ∼70 very minute ventral teeth on each thorn pad, while the number of teeth is clearly lower in M. biroi [18], and thorn pads appear even indistinct in H. pythonius according to Hennemann and Conle [38].

4.2 Concluding remarks

The current study is the first detailed characterization of major features of the external morphology of a stick insect belonging to the lineage Stephanacridini. The data discussed above highlighted a number of apomorphic character states that are known to define the Phasmatodea and major subordinated clades such as Euphasmatodea and Neophasmatidae.

To date, Stephanacridini appear to be still poorly understood from a morphological perspective, with only one potential autapomorphy supporting the monophyly of this taxon (i.e. the elongated gonapophysis 8 in the female postabdomen) [18]. Molecular systematics suggests that Stephanacridini and Lanceocercata are sister-groups [39,40], but we have not found synapomorphies to support this hypothesis. However, the present investigation on the male of H. leytensis yielded some new apomorphic features of mouthparts, attachment devices, and terminalia, which may support future investigations on the systematics of Stephanacridini. It is also apparent that the study of the maxilla of stick insects offers various relevant characters (e.g. presence/absence, size, and shape of the galealobulus; size and shape of the mediodistal portion of the galea; presence/absence, shape, and position of the trichome field; shape of the lacinia) but, as pointed out by Friedemann et al. [22], these features are still insufficiently documented in phasmatodean literature.

The taxonomic position of H. leytensis at the generic level remained ambiguous since the discovery of the species in 1997 [36]. Both the scarcity of available information and the distinctly different geographical distribution compared to the other species of Hermarchus (i.e. primarily found in Melanesia), made H. leytensis one of the most elusive stick insects of the Philippine fauna. Newly identified characters of male terminalia appear to challenge the taxonomic affiliation of H. leytensis within the genus Hermarchus s. str. (type species: Hermarchus pythonius), but any taxonomic change is currently premature. Indeed, the present results emphasize the need of further investigation on additional less well-known taxa that might belong to the Stephanacridini (see Hennemann and Conle [38,46,47]), through the acquisition of accurate morphological and molecular data combined with formal phylogenetic analyses.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Rolf Georg Beutel and Olivier Béthoux for valuable discussions about morphological characters, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript.