1 Introduction

Mutualisms are interspecific interactions involving two or more species where each partner obtains a benefit with positive implications for its fitness. Two main groups of arboreal ants (i.e. arboreal-nesting and -foraging species and ground-nesting, arboreal-foraging species) have evolved mutualistic associations with plants where each partner derives benefits [1]:

- • in the obligate mutualism involving myrmecophytes, the latter shelter specialized plant-ants in preformed cavities and usually provide them with food such as extra-floral nectar and/or food bodies. In return, plant-ants protect their host myrmecophyte from herbivores, competitors, encroaching vines and fungal pathogens;

- • territorially-dominant arboreal species (TDAs; e.g., weaver and carpenter ants plus carton-builders) have very populous colonies with large and/or polydomous nests, and defend territories both intra- and interspecifically from other TDAs.

Through their predatory behavior and aggressiveness, they protect their host trees from herbivorous insects. TDA colonies nest on certain tree species rather than others and, as for plant-ants, workers recruit nestmates in areas where host tree leaves are wounded by herbivores (induced defense), proving that the association is narrow [2,3].

The territoriality of both plant-ants and TDAs, particularly in the genus Azteca, prevents leaf-cutting ants and army ants from climbing up the trunks of their host trees ([4,5] and papers cited therein). Indeed, arboreal ants, including the TDA Azteca chartifex, can divert army ant columns from the base of their host trees by attacking them [5,6] or by depositing repellent compounds [7].

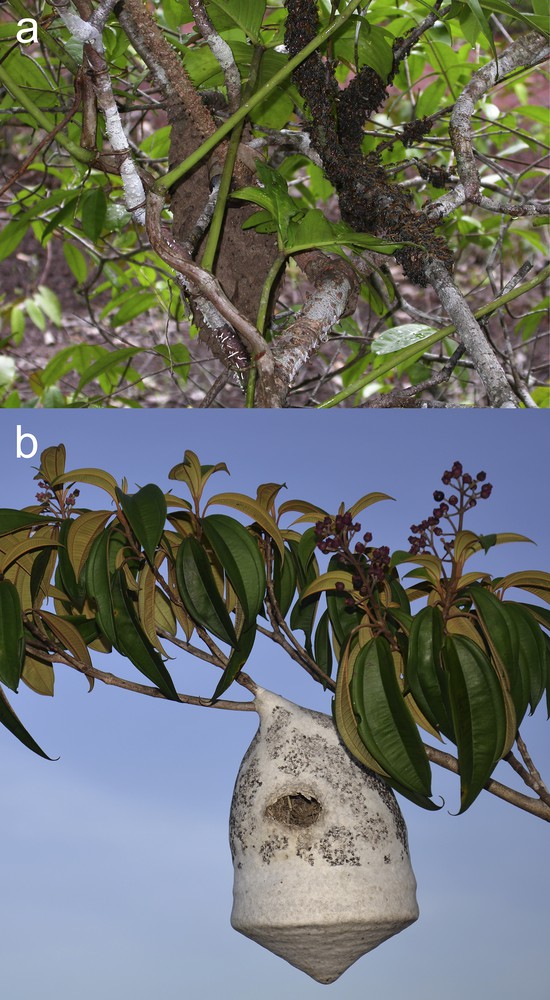

This anti-army ant behavior is thought to be exploited by social wasps that install their nest near the nests of plant-ants or TDAs [7–10]. Among them, the epiponine wasp, Polybia rejecta, has frequently been noted as associated with the large carton nests of A. chartifex. Generally, the nests are less than 50 cm from each other, but they can be in contact in certain cases; also, it can happen that several wasp nests surround an A. chartifex nest [10–13] (Fig. 1a). Thus, it is a challenge to know if this social wasp species is only an “exploiter” (i.e. a species obtaining a benefit from an association and that does not reciprocate), or, on the contrary, if it protects A. chartifex nests from vertebrate predation, mostly birds, something frequently asserted but never demonstrated.

(Color online.) a: a Polybia rejecta swarm close to an Azteca chartifex carton nest illustrating that the wasps arrive after the ants; b: a Chartergus artifex nest after being attacked by birds.

On the other hand, it is recognized that birds are predators of arboreal ants and social wasps [14–16]. Certain bird species strike wasp nests to cause the workers to abscond (i.e. abandon their nest) [17,18]. In the other cases, one can easily see the damage caused by the birds in gathering ant or social wasp brood: the opened thorns of myrmecophytic Acacia [19]; holes pierced in Cecropia trunks [20] or bamboo internodes [21] or directly in the walls of Azteca spp. carton nests or through the envelope of epiponine wasp nests (Fig. 1b).

Our aim was three-fold:

- • to verify, through a field survey, if the presence of P. rejecta protects A. chartifex colonies from bird predation as the damage can be extremely great;

- • to establish if P. rejecta nests are themselves frequently attacked by birds compared to two other social wasp species with large nests;

- • to compare the level of P. rejecta aggressiveness with that of seven other epiponine species common enough for standardized tests to be conducted.

2 Materials and methods

This survey was conducted between 2010 and 2014 at ten sites in coastal French Guiana situated between Sinnamary (5°22’N; 52°57’W) and Kaw Mountain (04°33’50”N; 52°12’22”W). During a campaign whose goal was to locate A. chartifex nests (October 2010-October 2011), we firstly identified intact A. chartifex carton nests from those having already been damaged by birds and then noted if the nest was near a P. rejecta nest or not. We also verified if the P. rejecta nests were themselves attacked by birds when not associated with ants, and did the same for two other epiponine wasps with large nests. Further controls were made in October 2012 and 2013; the detailed observation of woodpeckers attacking an A. chartifex nest was made in June 2014. Comparisons were made using Fisher's exact-test and false discovery rate for multiple comparisons, BH correction [22].

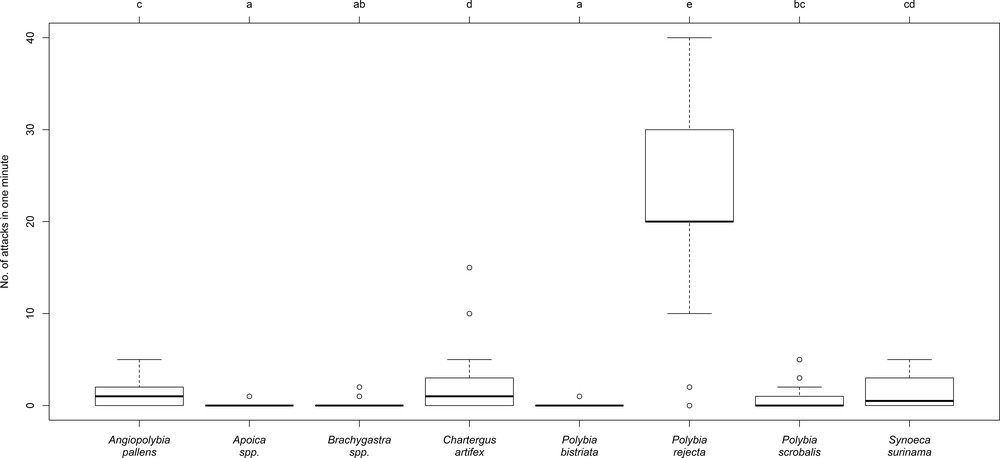

In order to evaluate the degree of aggressiveness among eight epiponine wasp species, including P. rejecta, we firstly located wasp nests situated at an adequate height for study. The experimenter wore a blue anti-hornet suit whose black rectangular-shaped screen (15 × 17 cm), situated in front of his eyes, contrasts with the color of the suit, so that the screen is attacked by the wasps rather than the rest of the suit. The experiments were repeated 30 times (only 20 times for Chartergus artifex, which is much less common). The experimenter, who already knew exactly where each targeted wasp nest was located, approached it from the side, hidden by the foliage of the forest edge. Then, he quietly stepped in front of the nest, stopping at a distance of about 80 cm and counted the number of attacks during 1 minute. Any attack that occurred prior to the moment he stopped was not counted. These experiments were conducted in October 2013 (the dry season) between 11 a.m. and 4 p.m. on non-consecutive days with no wind or with only a slight breeze. For Polybia bistriata, which is very prevalent, 30 different nests were tested (only once each). For the other species, two trials were conducted; they were separated by one month or more to prevent the same workers from being involved in different attacks (foragers are already old workers and the total lifespan of workers in another Epiponine wasp with large nests is 20–25 days [23]). We modeled the link between the number of times the screen was attacked by the wasps using a generalized linear model (GLM) with a Poisson distribution. The results were compared using Tukey's honest significance test (we inserted a hypothetical attack by Apoica spp. to avoid problems associated with ‘zero’ without affecting the results).

Statistical analyses were conducted using R software [24].

3 Results and discussion

The A. chartifex carton nests were never attacked by birds when there was a P. rejecta nest in their proximity (i.e. less than 50 cm; 42 cases), whereas, when there was not a wasp nest, nine out of 88 (10.2%) nests were attacked, the difference being significant (Fisher's exact-test: P = 0.03). Among the birds attacking A. chartifex nests, woodcreepers (Dendrocolaptinae) and particularly woodpeckers (Picidae) were easily recognizable (six series of observations; Fig. 2; see the video in the supplementary material http://dl.free.fr/bznvQfiI4).

(Color online.) Cream-colored woodpeckers (Celeus flavus) attacking an Azteca chartifex carton nest to eat the brood: a: note that the bird uses its tail to support itself; b. workers are counter-attacking the bird, crawling on its legs whose scales provide protection from the ant bites (dolichoderine ants are stingless). The ants are likely stopped by the down situated on the tibio-tarsal articulation; c: two individuals sharing the meal.

During the field surveys, we witnessed the presence of a P. rejecta swarm ready to build its nest in the proximity of an A. chartifex nest 16 times (Fig. 1a). The nests of this species were noted as being associated with an A. chartifex nest in 61 cases and with a colony of Dolichoderus bidens once; they were isolated in two cases [10].

The envelope of P. rejecta nests was never attacked by birds either when associated with A. chartifex or when the nests were isolated (a total of 59 cases). By comparison, five Chartergus artifex nests out of 18 (27.8%) were attacked by birds (Fig. 1b) as well as four Epipona tatua nests out of 18 (22.2%). The difference between P. rejecta and each of these two wasp species was significant, while it was not between them (Fisher's exact-test and BH correction: P. rejecta vs. C. artifex: P = 0.026; P. rejecta vs. E. tatua: P = 0.021; C. artifex vs. E. tatua: P = 0.50). These results are likely due to the high level of P. rejecta aggressiveness compared to that of the seven other species compared (Fig. 3). Among them, the nocturnal Apoica spp. never attacked under the experimental conditions (they can attack if the nest is disturbed). Angiopolybia pallens workers frequently exit their nests to settle on the envelope with their wings in a V-shape as a warning signal, and Synoeca surinama workers tap their gasters on their nest envelope to produce a drumming sound; however, individuals from both species only rarely attacked.

Comparison of the degree of aggressiveness between eight epiponine social wasps. The values correspond to attacks directed at the rectangular-shaped (15 × 17 cm) screen of an anti-hornet suit situated in front of the eyes of the observer. Statistical comparisons: different letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 (n = 30 cases for each wasp species; only 20 cases for Chartergus artifex; much less common).

It has been noted that some social wasps, such as P. bistriata, are only mildly aggressive [17], but all tested species can attack when disturbed (a slight vibration of the branch supporting their nest is enough). Yet, a strong disturbance causes them to abscond, a behavior exploited by caracaras [17,18] and some woodcreepers (S. McCann, pers. obs.). Several factors can make epiponine wasps abscond, including attacks by army ants, bats, other animals, or artifacts such as falling branches [25]. On the contrary, P. rejecta was by far the most aggressive (this study; see also [13]), and its sting is very painful [26], but less so than that of Synoeca [27].

Because it is well established that A. chartifex protects P. rejecta from army ants and because we have shown that P. rejecta efficaciously protects the A. chartifex nests from bird predation through its aggressiveness, we can truly call the A. chartifex–P. rejecta association a protective mutualism.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Yockey-Dejean for proofreading the manuscript, and the Laboratoire environnement de Petit-Saut for furnishing logistical assistance.