1 Introduction

Kimulidae is a family of sturdy and bumpy Zalmoxoidea, second only to Zalmoxidae in diversity within the superfamily (10 genera, 36 species), known mostly from Venezuela, the Greater Antilles and also isolated in NE Brazil and caves in SE Brazil [1–3]. They are dull brown colored animals, inhabiting the leaf litter. Pérez-González et al. [3] had already reported many undescribed kimulids from Central America and northwestern South America. Herein we formally describe the first member of this family from Colombia, thus expanding the range of the family hundreds of km southwestwards into the Andes mountain range.

A possible synapomorphy for the family is the set or girdles or flanges present on the pars distalis of penis, the so-called lamina inferior [4] or lamina ventralis [3]. These flanges are flattened and horseshoe-shaped, encircling the capsula interna from the ventral side to touching (or at least getting closer) its left and right tips on the dorsal side.

2 Material and methods

Specimens were photographed using a Leica M205C stereoscope attached to a Leica DFC450 digital camera and were posteriorly edited in Photoshop CC 2014 software. Drawings of the species were made using Inkscape 0.91 software and CorelDRAW v.20.0. Scanning Electron Microscopy was carried out with a scanning electron microscope (Jeol JSM-6390LV) belonging to the Rudolf Barth Electron Microscopy Platform of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute/Fiocruz.

The morphological descriptions follow Pérez-González et al. [3], Kury and Medrano [5] for dorsal scutum, coda and other anatomic terms. Descriptions of colors use the standard names of the 267 Color Centroids of the NBS/IBCC Color System [6] as described in Kury and Orrico [7].

Abbreviations cited: AW = maximum abdominal scutum width, CL = carapace length, CW = maximum carapace width, DS = dorsal scutum, DSL = dorsal scutum length, PB = pars basalis, PD = pars distalis, Tr = trochanter, Fe = femur, Pa = patella, Ti = tibia, Mt = metatarsus, Ta = tarsus.

The set of horseshoe-shaped girdles that embrace and cover the capsula interna was called “lamina inferior” by Sørensen in [4] and “lamina ventralis” by Pérez-González et al. [3]. Such names are neutrally descriptive; however, we think that the use of lamina ventralis (which translates as “ventral plate”) might bring an undesirable idea of homology between this structure and the ventral plate present in Gonyleptoidea, even giving the name to the taxon Laminata [8,9]; therefore, we prefer to use the term “lamina inferior” in this work. The lamina inferior is made up by a set of girdles herein called U-flakes. Tarsal formula: numbers of tarsomeres in tarsus I to IV, when an individual count is given, order is from left to right side (the figures in parentheses denote the number of tarsomeres only in the distitarsus I–II). All measurements are in mm.

The studied material is deposited in MNRJ (Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Curator: Adriano B. Kury).

3 Critical systematic background

What is now called Kimulidae started with Sørensen (in Henriksen) [4], who erected the Minuidae containing the seven new genera Acanthominua Sørensen, 1932, Euminua Kury and Alonso-Zarazaga, 2011, Kalominua Sørensen, 1932, Microminua Sørensen, 1932, “Minua” Sørensen, 1932, Minuides Sørensen, 1932 (all from Venezuela), and Phera Sørensen, 1932 (from southern Brazil). In a work very meager in illustrations, it is surprising to find some images of male genitalia for species of Minuidae, which are crude, but nevertheless, allowed future familial assignments. Two of the included genera, Minua and Euminua, were invalid because described after 1930 without designation of a type species, but it took six decades for this fact to be noticed. Sørensen's Minuidae were included in the superfamily Phalangodoidea by the editor of his posthumous work [4], along with many subfamilies of Phalangodidae recently described by Roewer. Henriksen [4] made it clear that Sørensen's families corresponded to Phalangodidae subfamilies as used by Roewer [10]. Mello-Leitão [11] tried to accommodate the new families created by Sørensen (vaguely suggesting including Minuidae in Phalangodinae) into Roewer's system, by demoting them to subfamilies of Phalangodidae. He also created yet another subfamily, the Minuidinae Mello-Leitão, 1933, composed by two monotypic genera: Minuides Sørensen, 1932 and Pseudominua Mello-Leitão, 1933 (dismembered from Euminua). Mello-Leitão [12] further dismembered Euminua, creating the monotypic genus Euminuoides Mello-Leitão, 1935.

Mello-Leitão [13] decided to accept Minuinae as a subfamily separated from the Phalangodinae, with the exception of Microminua, which went to the Phalangodinae. Microminua was returned to Minuidae by Kury [14], and finally transferred to Samoidae by Kury and Pérez-González [15], who synonymized Cornigera González-Sponga, 1987 with it.

Goodnight and Goodnight [16] were ultra-Roewerian in not recognizing Minuinae as distinct from Phalangodinae, and by describing in this subfamily the new monotypic genus Kimula Goodnight and Goodnight, 1942, from Puerto Rico, which was later recorded also from Cuba [17].

Roewer (e.g., [18]) never cited Minuinae either as a separate family or as a subfamily of Phalangodidae. He created the new monotypic genus Minuella Roewer, 1949 by dismembering from Minua. He never noticed that Minua was invalid, as wrongly suggested later by González-Sponga [19]. Roewer, in the same paper, described in Phalangodinae the monotypic genus Tegipiolus Roewer, 1949 from NE Brazil, only much later discovered to be a kimulid.

H. Soares [20] inflated the fictitious SE Brazilian representation of Minuinae, describing two new genera from southeastern Brazil: Pirassunungoleptes H. Soares, 1966 (transferred to Zalmoxidae by Kury [14]) and Spaeleoleptes H. Soares, 1966 (transferred to Escadabiidae by Kury and Pérez-González [21]).

Šilhavý [22] increased the knowledge of the family (which incidentally he did not recognize as such) from Cuba, by describing some new species of Kimula, accompanied by beautiful drawings of the habitus of males and images of the extravagant male genitalia of this genus. Avram [39] erected the new subgenus of Kimula, Metakimula Avram, 1973 along with a new species from Cuba. Šilhavý [23] and González-Sponga [19] considered both subfamilies Minuinae and Minuidinae as synonyms of Phalangodinae.

González-Sponga [19] mistakenly concluded from Roewer's paper that Minua was a synonym of Minuella: “Roewer (1949: 40) crea el género Minuella colocando como sinonimia de este a Minua Sorensen, 1932.” What in fact happened is that Roewer only picked out one species of Minua to create Minuella (although he cited no difference between both alleged genera, presenting only a non-comparative diagnosis for Minuella). But in the end González-Sponga's usage of Minuella somehow proved to be right, because Minua was much later discovered to be invalid.

Kury [24], puzzled by the dissonant southern Brazilian distribution of the genus Pherania Strand, 1942 (originally called Phera Sørensen, 1932, but preoccupied by a genus nomen in Hemiptera), studied the type material of Phera pygmaea Sørensen, 1932, and discovered its gonyleptid affinities, placing it at first in Pachylinae and later into the synonymy of Tricommatus Roewer, 1912 in Tricommatinae [8].

In his unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Kury [25] recognized a large superfamily Zalmoxoidea, including Biantidae, Minuidae, Podoctidae, Samoidae, Stygnommatidae and Zalmoxidae, but this name appeared in press only much later [26].

González-Sponga [27] erected in Phalangodinae the monotypic genus Fudeci González-Sponga, 1998, from a tepui in Bolívar, Venezuela. This was transferred later by Kury [14] to Minuidae. Pérez-González [35] reviewed the genus Kimula in an unpublished MSc dissertation.

Kury [14] reestablished Minuidae as a distinct family, enlarging it with the inclusion of some Antillean (Kimula, Metakimula, this elevated from subgenus) and Venezuelan (Fudeci) genera of Phalangodinae and both genera of Minuidinae (Minuides, Pseudominua), while transferring three other genera (Kalominua to Samoidae, Pirassunungoleptes to Zalmoxidae, Spaeleoleptes to family uncertain). Kury's catalogue [14], in spite of being published only in 2003, was prepared in the late 1990s and sat waiting for a suitable channel for publication. Meanwhile, a new ICZN Code was published, and Kury overlooked Article 16.1, which stated that new names published after 1999 should be explicitly proposed as new, also overlooking that Minua and Euminua did not fulfill the requirements of Article 13.3, being published after 1930 without designation of a type species, which also affected the name Minuidae.

Alonso-Zarazaga teamed up with Kury to prepare a list of addenda and (nomenclatural) corrigenda to the 2003 catalogue [28], and he was the first to detect the problem with the nomen Minuidae, but before this was ready for publication, a rushed teamwork project (a famous Opiliones textbook [29]) demanded that a replacement name was given to the Minuidae. Roughly at the same time, Pérez-González [30] made a substantial Ph.D. thesis on Stygnommatidae, supervised by A.B. Kury, and commented on Kimulidae, its nomenclature, morphological key features and possible kinship with Escadabiidae. In the 2006 thesis, Pérez-González suggested that Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides, Minuides, and Pseudominua should all be transferred to Zalmoxidae (all of these were formalized in print later). Some information from this thesis ended up in in a chapter of the Opiliones textbook [31], including the new name for the family, Kimulidae, as the authors did not like alternatives such as “Minuellidae”. Pérez-González and Kury [31] also included Tegipiolus from NE Brazil in Kimulidae and transferred Minuides to the Zalmoxidae, automatically carrying the synonymy of the Minuidinae. Kury and Alonso-Zarazaga [28] at long last formally described Euminua.

Kury and Pérez-González [15] transferred Microminua from Kimulidae to Samoidae; however, the second species of Microminua (Microminua soerenseni Soares and Soares, 1954, from SE Brazil) was transferred to Tibangara Mello-Leitão, 1940, in Cryptogeobiidae.

Finally, Pérez-González et al. [3] described a new monotypic genus, Relictopiolus Pérez-González, Monte and Bichuette, 2018, from a cave system in SE Brazil, and formalized the transfer of some false kimulids (Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides and Pseudominua) to Zalmoxidae. They also presented a molecular phylogeny in that Kimulidae appeared nested inside Escadabiidae and commented on the so far unrecorded distribution of Kimulidae. The expansion of the records of the family from Colombia appeared recently several times in congress abstracts [36–38].

Giribet and Kury [32] divided Kury's superfamily Zalmoxoidea into Zalmoxoidea (Icaleptidae, Guasiniidae, Zalmoxidae + Fissiphalliidae), and Samooidea (Samoidae + Podoctidae + Biantidae + Minuidae + Stygnommatidae). Giribet et al. [33] included in Zalmoxoidea the same Fissiphalliidae, Guasiniidae, Icaleptidae, and Zalmoxidae, with a paraphyletic Samooidea as a sister group. Sharma and Giribet [34] augmented Zalmoxoidea transferring Escadabiidae and Kimulidae to it, resulting in six included families (Escadabiidae, Fissiphalliidae, Guasiniidae, Icaleptidae, Kimulidae, Zalmoxidae), while Samooidae had (Samoidae + Biantidae + Stygnommatidae). Since this, the inclusion of Kimulidae in Zalmoxoidea has not been challenged (e.g., Sharma and Giribet [40]).

4 Systematic accounts

KIMULIDAE PÉREZ-GONZÁLEZ, KURY AND ALONSO-ZARAZAGA, 2007

- •

Minuidæ Sørensen in Henriksen 1932: 227 (incl. Acanthominua, Euminua, Kalominua, Microminua, Minua, Minuides, Phera). Type genus by original implicit etymological designation: Minua Sørensen, 1932 [stem: Minu-], invalid senior subjective synonym of Minuella Roewer, 1949 by González-Sponga (1987). ‡ Familial nomen permanently invalid, being based on an unavailable genus nomen, published without designation of a type species after 1930 (ICZN Code Art. 13.3).

- Minuinae [subfamily of Phalangodidae]: Mello-Leitão 1938: 137 (incl. Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides, Kalominua, Minua, Phera); H. Soares 1966: 110 (incl. Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides, Kalominua, Minua, Phera, Pirassunungoleptes, Spaeleoleptes). ‡ Apohypse (first use as subfamily).

- Minuidae: Kury 2003: 211 (incl. Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides, Fudeci, Kimula, Metakimula, Microminua, Minua, Minuides, Pseudominua). ‡ Apograph (without ligature).

- •

Kimulidae Pérez-González, Kury and Alonso-Zarazaga in Pérez-González and Kury 2007: 207 (incl. Acanthominua, Euminua, Euminuoides, Fudeci, Kimula, Metakimula, Microminua, Minuella, Pseudominua, Tegipiolus).

- Kimulidae–Pérez-González et al., 2017: 16 (incl. Fudeci, Kimula, Metakimula, Minuella, Relictopiolus, Tegipiolus).

Included genera.Fudeci González-Sponga, 1998, Kimula Goodnight and Goodnight, 1942, Metakimula Avram, 1973, Minuella Roewer, 1949, Relictopiolus Pérez-González, Monte and Bichuette, 2017, Tegipiolus Roewer, 1949 and Usatama gen. nov.

Usatama gen. nov.

Type species.Usatama infumatus sp. nov.

Etymology. Named after Usatama (or Uzathama), heroic chieftain of the Chibcha Sutagao people, who inhabited what is today the municipality of Silvania. Gender masculine.

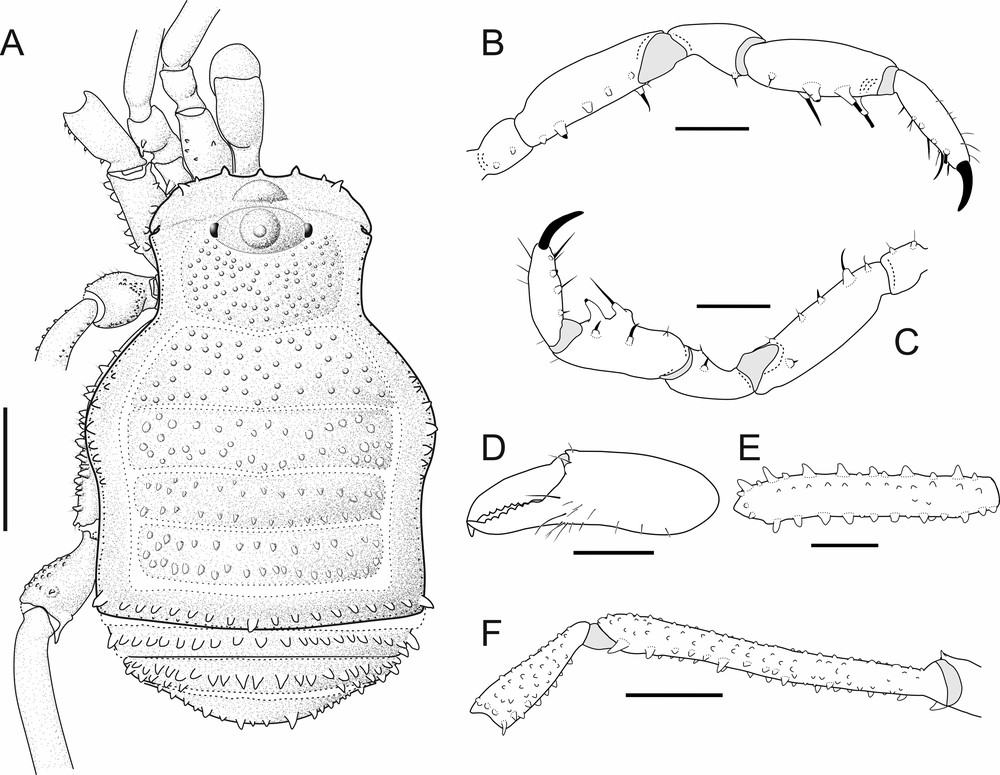

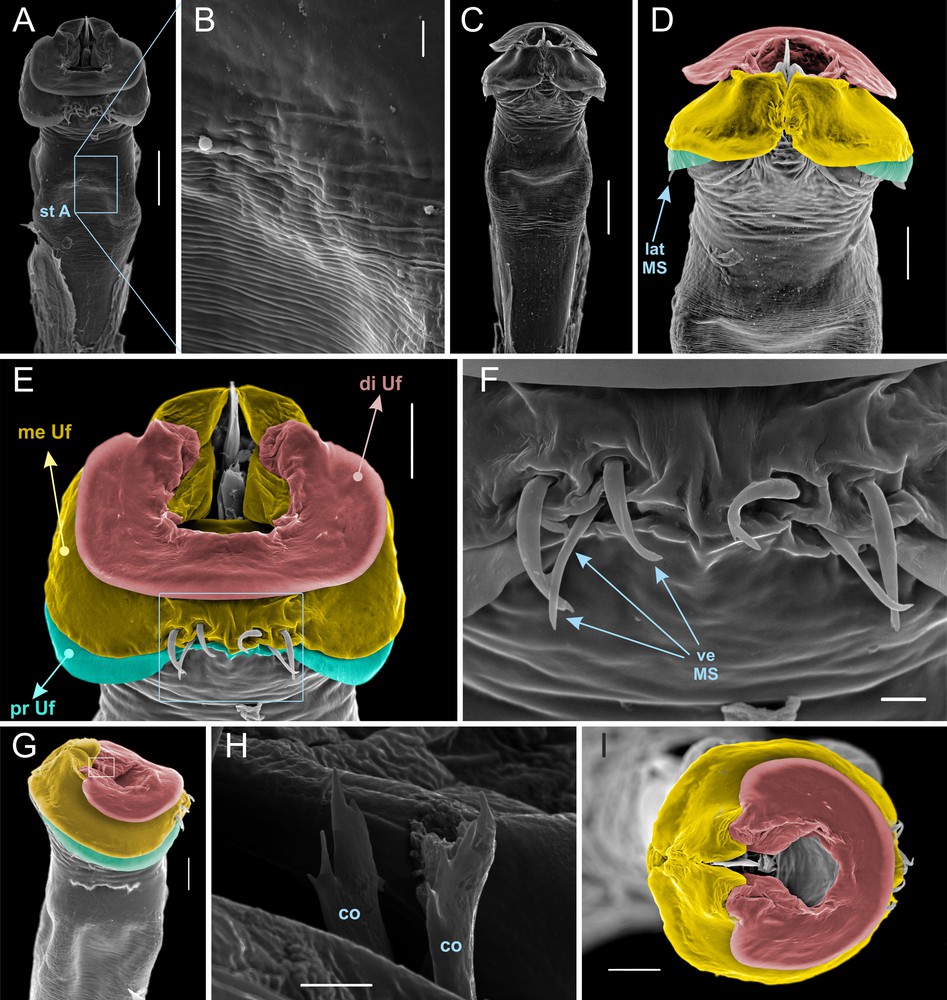

Diagnosis. Large kimulid (3.7 mm DS) with slender and elongate leg IV in males (Fig. 1E; contrasting with Tegipiolus, Relictopiolus, Metakimula and Kimula). Differs from other genera of Kimulidae by having a small erect tubercle in ocularium (Figs. 1B, 1C; instead of large and hooked forward or backwards) and preocular mound well developed and separated from ocularium by a depression (Figs. 1C, 2A). Dorsal scutum type theta (θ) with bulge and parallel-sided coda well differentiated by a constriction marked at area III level (Figs. 1A, 2A; as in Minuella, contrasting with abdominal scutum flaring with exceedingly slight constriction as in Fudeci, Relictopiolus, Tegipiolus; no constriction whatsoever with laterals converging or parallel in Kimula, Metakimula). Without prominent spines or tubercles in mesotergum or free tergites (Fig. 1A, 2A; contrasting with free tergite III armed with stouter median spine in Kimula, Metakimula and with mesotergum and tergites provided with rows of thick protuberances in Relictopiolus, and also with lateral projections in FT I and/or II in Minuella). Free sternites without special armature (contrasting with Kimula and Metakimula). Fe IV sexually dimorphic, in male non-incrassate, but longer and less curved, armed with a few short proventral spines (Figs. 1E, 1F; as in Minuella, contrasting with incrassate and provided with spines in Kimula, Metakimula, Relictopiolus, Tegipiolus). Tarsal counts 4-14-4-4. Leg I with 4 tarsomeres is the rule in kimulids (only Fudeci, Relictopiolus and Tegipiolus have 3). Leg II with 14 tarsomeres is the maximum number in the family (most species have around 7–11, while Fudeci, Relictopiolus and Tegipiolus have 4–5). Leg III with 4 tarsomeres is the minimum in the family (which all have 5, except Relictopiolus also with 4). Leg IV with 4 tarsomeres is unique in the family (species of all other genera have 5–6). A detailed comparison of male genitalia may be found in the discussion section, herein a brief characterization of it in Usatama is given: Truncus polyhedral with slight and gradual thickening (Figs. 3A, 3C) with extensive striated region all around it (Fig. 3B). Groove or socket absent (Figs. 3A, 3C, 3D). Three well-marked U-flakes, which are more or less perpendicular to the main axis of truncus (Figs. 3D, 3E, 3G, 3I); distal U-flake is smaller and its tips do not meet dorsally (Fig. 3E, red area); medial U-flake is enormous, with its tips meeting dorsally, where the conductors rest (Figs. 3D, 3I, yellow area); proximal U-flake is mostly concealed under the medial one (Figs. 3D, 3E, 3G, green area). Macrosetae: one pair of short spatulate lateral MS, mostly hidden by the proximal U-flake (Figs. 3D, 3G); three pairs of short cylindrical ventral MS on the medial U-flake (Figs. 3E, 3F). Conductors moderately-sized (Figs. 3G, 3H).

Usatama infumatus sp. nov. A. Male holotype (MNRJ 60264), dorsal view. B. Same, lateral view. C. Same, frontal view. D. Same, ventral view. E. Same, habitus dorsal view. F. Female paratype (MNRJ 60382), habitus dorsal view. Abbreviations: Pr Mo (preocular mound); Su 1 (mesotergal sulcus I). Scale bars: 1 mm.

Usatama infumatus sp. nov. (MNRJ 60264) male holotype, schematic. A. Dorsal view. B. Right pedipalp, ectal view. C. Left pedipalp, mesal view. D. Right chelicera, dorsal view. E. Left femur I, retrolateral view. F. Right femur IV, prolateral view. Scale bars: 1 mm.

Usatama infumatus sp. nov. (MNRJ 60264) holotype, penis. A. Ventral view, panoramic. B. Same, detail of striated area (st A). C. Dorsal view, panoramic. D. Same, distal part. E. Distal part, ventral view. F. Same, detail of the ventral setae. G. Distal part, dextrolateral view. H. Conductors (co), detail, oblique view. I. Distal part, apical view. Colored areas: distal U-flake (di Uf, red); medial U-flake (me Uf, yellow); proximal U-flake (pr Uf, green). Scale bars: 100 μm (A, C); 50 μm (D, E, G, I);10 μm (B, F) and 5 μm (H).

Usatama infumatus sp. nov.

Type data. holotype (MNRJ 60264) and four paratypes (MNRJ 60382) from Colombia, Cundinamarca, Silvania, Condomínio El Pedregal (4°23’30.07” N; 74°23’43.15” W), 1520 m. WWF Ecoregion: NT0136 (Magdalena Valley montane forests). High Andean forest, between trunks and leaf litter. 30–31.xi.2018, D. Ahumada, C. López, H. Vides and Y. Carpio leg.

Etymology. From Latin adjective infumatus (smoked), which is a direct translation of the Spanish surname Ahumada. From our friend and collector of the type series, Daniela Ahumada.

Description ofholotype. Measurements: DSL: 3.65, CL: 1.22, CW: 1.75, AW: 2.80. Pedipalp: Tr: 0.34, Fe: 0.90, Pa: 0.56, Ti: 0.84, Ta: 0.75. Leg I: Tr: 0.46, Fe: 1.52, Pa: 0.75, Ti: 1.15, Mt: 1.66, Ta: 1.03. Leg II: Tr: 0.63, Fe: 3.27, Pa: 2.06, Ti: 2.79, Mt: 4.06, Ta: 3,17. Leg III: Tr: 0.47, Fe: 1.57, Pa: 0.66, Ti: 1.39, Mt: 1.80, Ta: 1.15. Leg IV: Tr: 0.85, Fe: 3.28, Pa: 1.39, Ti: 3.05, Mt: 3.73, Ta: 1.41.

Dorsum. Entire body granulated, scutum magnum bell-shaped (type theta) with the mesotergal areas of approximately the same width, but wider at the level of areas I–II (bulge); scutum outline with well-marked constriction at sulcus I (Figs. 1, 2A). Abdomen 1.6 times wider than carapace. Posterior margin of the scutum slightly convex. Anterior margin of carapace slightly convex with two antero-lateral tubercles each side, cheliceral sockets well-marked (Figs. 1A, 2A). Anterior region of carapace with a prominent preocular mound differentiated from the ocularium (Figs. 1B–C). Conspicuous ocularium, granulated, with an erect conical low spine (Figs. 1A–C, 2A). Mesotergum slightly convex with five unarmed areas without medial division (Figs. 1A, 1B, 2A). Lateral borders of abdomen with some tubercles in the bulge and one acuminated tubercle in the postero-lateral corners (Fig. 1B); area I longer (along the anterior–posterior axis) than remaining areas. Mesotergal sulci complete and straight, except sulcus III that is medially V-shaped; area V with a transverse row of tubercles (Fig. 1A). Free tergites each with one transverse row of tubercles (Figs. 1A–B). Coxa IV scarcely visible in dorsal view (Fig. 2A).

Venter. Coxae I–IV granular. Coxae I and II remarkably procurved, III short and straight, and IV large and projected backwards. Coxae II and IV with rounded tubercles in retrolateral and prolateral regions, respectively (Figs. 1A, 1D, 2A). Coxa IV with a conical retro-lateral tubercle at posterior border (Fig. 1D). Free sternites each with a transverse row of prominent acute setiferous tubercles (Figs. 1A, 1B, 1D, 2A). Anal operculum covered by many low tubercles and spiracles oval (Fig. 1D).

Chelicera. Basichelicerite unarmed with a well-marked rounded bulla. Cheliceral hand unarmed, not swollen, with several sensilla on mesal region. Movable and fixed finger each with seven uniform rounded teeth (Figs. 1B, 2A, 2D).

Pedipalp. Coxa short, unarmed, finely granulated. Trochanter globular, with two ventral small setiferous tubercles. Femur armed with a ventroectal row of five setiferous tubercles (the second basalmost larger than the others) and one mesodistal medium-sized setiferous tubercle. Patella cylindrical, armed with one ventroectal and one ventromesal setiferous tubercles. Tibia armed ventrally with two mesal and three ectal setiferous tubercles (the basalmost smaller than the others, the medial one raising on a protuberance). Tarsus dorsally with sparse sensilla and ventrally with four ectal and four mesal setiferous tubercles (Figs. 2B, 2C).

Legs. Legs I–IV granulate; Fe I with one dorsal row of tubercles of different sizes and two ventral rows of tubercles of equal size (Figs. 1D, 2E). Tr IV with one dorso-distal tubercle and one retrolateral distal acuminate tubercle (Figs. 1D, 2F); Fe IV same size of DS length, with one prolateral and one retrolateral row of tubercles (the distalmost larger than the others and projected backwards); Pa IV with a distal acuminate tubercle in the prolatero-ventral face (Fig. 2F). Tarsal formula: 4(2)/14(2)/4/4.

Male genitalia (Fig. 3). Same as in genus diagnosis.

Color (in alcohol, Fig. 1). DS Dark Brown (59), sulci Deep Brown (56); coxae, trochanters, stigmatic area, chelicerae and pedipalps Dark Orange Yellow (72), Femora to tarsi I–IV Dark Brown (59) with Dark Orange Yellow (72) rings in Fe and Ti I–IV.

Female. Paratypes measurements (n = 4, Min–Max): DSL: 3.17–3.53, CL: 1.16–1.28, CW: 1.48–1.69, AW: 2.31–2.66; Pedipalp: Tr: 0.26–0.31, Fe: 0.66–0.85, Pa: 0.44–0.51, Ti: 0.62–0.71, Ta: 0.44–0.65; Leg I: Tr: 0.33–0.40, Fe: 0.93–1.10, Pa: 0.47–0.61, Ti: 0.74–0.84, Mt: 1.10–1.13, Ta: 0.74–0.78; Leg II: Tr: 0.46–0.51, Fe: 1.51–1.75, Pa: 0.82–0.95, Ti: 1.15–1.24, Mt: 1.65–1.97, Ta: 1.61–1.73. Leg III: Tr: 0.39–0.52, Fe: 0.97–1.08, Pa: 0.46–0.53, Ti: 0.78–0.92, Mt: 1.14–1.37, Ta: 0.79–0.92. Leg IV: Tr: 0.53–0.61, Fe: 1.50–1.81, Pa: 0.79–0.88, Ti: 1.44–1.66, Mt: 2.05–2.24, Ta: 0.82–1.04.

Similar to male except for: 1) leg IV sexually dimorphic (shorter and thicker in females), 2) DS with constriction more accentuated; coda divergent (parallel in male), 3) absence of acuminated tubercles in the postero-lateral corners of DS (Figs. 1E, 1F).

Distribution. Known only from the type locality.

5 Discussion

5.1 Distribution of kimulids (Fig. 4)

All species of Kimulidae inhabit forested areas, mostly of WWF type 01, but also 02 and 03. Most species lie between the altitudinal range of 100 m and 1400 m. The species farthest from the central distribution core are those of Tegipiolus (from humid enclaves in xeric regions) and Relictopiolus (obligate cave-dweller from the Atlantic Dry Forests). There is no record of the family from the Lesser Antilles, and Kimula/Metakimula occur in the Greater Antilles in moist and dry forests and even in Pine forests in Hispaniola. The most diverse genus Minuella occurs only in montane forests, in two Venezuelan nuclei: the Coastal Range and the Andes (Cordillera de Mérida, where its reaches 2500 m, the maximum altitude for the family). Fudeci occurs only on the slope of a tepui in SE Venezuela. Usatama occurs on the slope of the easternmost Colombian mountain range, more or less contiguous with the Venezuelan Andes.

Central Neotropics, showing the distribution of the genera of Kimulidae.

5.2 Comparison of male genitalia among kimulids

The male genitalia of Fudeci curvifemur as depicted in the original description are extremely schematic, avoiding a detailed appraisal, but apparently they strongly resemble those of Minuella. In most Kimulidae, the thin cylindrical truncus pars basalis (PB) grows abruptly thicker distally as a deeply striated region (as in Kimula, Metakimula, Minuella, and Tegipiolus). In Usatama, the truncus is more polyhedral and the thickening is slight and gradual. The PB is separated from pars distalis (PD) by a deep groove in Kimula and Minuella, and PD fits into an apical socket in PB in Tegipiolus. A groove or socket are absent in Usatama. There may be two groups of macrosetae on pars distalis of kimulids: the lateral/dorso-lateral and the ventral. Tegipiolus: 4 pairs of huge spatulate MS arranged in an oblique row from lateral to dorsal; only 1 pair of small cylindrical ventro-lateral MS. Minuella: 3–4 pairs of huge tubular dorso-lateral MS arranged in a vertical row; no ventral MS. Kimula: 3–4 pairs of huge spatulate dorso-lateral MS arranged in a vertical row; no ventral MS. Metakimula: 2 pairs of short cylindrical lateral MS arranged in a slanted row; 2 pairs of similar ventral MS. Usatama: 1 pair of short spatulate lateral MS, mostly hidden by the proximal U-flake; 3 pairs of short cylindrical ventral MS on the medial U-flake. Usatama may also be separated from the other genera by possessing 3 well-marked U-flakes, which are more or less perpendicular to the main axis of the truncus; the apical U-flake is smaller and its tips do not meet dorsally, while the medial U-flake is enormous, with its tips meeting dorsally, where the conductors rest. The proximal U-flake is mostly concealed under the medial one. In other Kimulidae, the distal U-flake is much reduced and erect, the medial U-flake is much more developed than the others, while the proximal U-flake is only a lobe attached to it. Usatama can also be distinguished from Tegipiolus by the normal size of the conductors, which in Tegipiolus are enormously developed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) under Scholarship # 306411/2015-6 (Bolsas no País/Produtividade em Pesquisa–PQ 2015: Sistemática de Opiliones Neotropicais, com foco em Gonyleptoidea (Arachnida, Opiliones)) and Grant # 477502/2012-1 (Chamada Pública MCT/CNPq–no. 14/2012–Universal: Taxonomia, caracterização e identificação de Laniatores (Arachnida, Opiliones) do Neotrópico: famílias Cosmetidae, Cranaidae e Gonyleptidae) to ABK; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ, Apoio Emergencial ao Museu Nacional) under scholarship # E-26/200.085/2019 to ABK, scholarships from the Coordenação de aperfeiçoamento de pessoal de nível superior (CAPES) to AFG and MM. The SEM micrographs were taken in the Rudolf Barth Electron Microscopy Platform of the Oswaldo Cruz Institute/Fiocruz, with the assistance of Roger Magno Macedo Silva and Wendell Girard Dias. We would like to thank our friend the arachnologist Daniela Ahumada (Universidad de Cartagena, Colombia) for presenting the type series of U. infumatus for the present study and to Abel Pérez-González (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, Buenos Aires) for more than generously sharing his unpublished notes and illustrations on kimulids and also for his important suggestions and criticism on a draft.