1 Introduction

Heart transplantation is the ultimate therapy for the treatment of severe heart failure. However, it has not been widely examined, because it requires donor hearts. The inadequate supply of donor hearts is often a major problem everywhere in the world. As a result, the current challenge in cardiology is how to reserve pump failure by cell transplantation or regenerative medicine. Recent studies have shown that transplanted fetal cardiomyocytes can survive in heart scar tissue and that the transplanted cells limit scar expansion and prevent post-infarction heart failure. Transplantation of cultured cardiomyocytes into damaged myocardium has been proposed as a future method of treating heart failure 〚1, 2〛. This revolutionary concept remains unfeasible in clinical settings because of the difficulty of obtaining donor fetal hearts. Thus, a cardiomyogenic cell line has long been awaited, and such a line might be capable of substituting for fetal cardiomyocytes in this therapy.

Various studies have demonstrated that cardiomyocytes can differentiate from multipotent stem cells, such as embryonic stem (ES) cells 〚3〛 and embryonic carcinoma (EC) cells 〚4〛. ES cells are an attractive cell source in regenerative medicine, but the recipients must take immunodepressant drugs throughout their lives, because the transplanted ES cells are allogeneic. Use of these reagents impairs the quality of life of the recipients, and transplantation of undifferentiated ES cells often causes teratocarcinoma. In addition, the establishment of human ES cells involves ethical problems and is not allowed in every country. Because of these circumstances, the regeneration of cardiomyocytes from adult autologous stem cells has been awaited.

Recent reports have demonstrated the existence of pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues. Roy et al. reported the existence of neural stem cells in the brain that can differentiate into neurons, oligodendrocytes, and astrocytes in vitro 〚5〛. Marrow stromal cells have been shown to possess many characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells 〚6〛, and pluripotent progenitor marrow stromal cells can differentiate into various types of cell types, including osteoblasts 〚7, 8〛, myocytes 〚9〛, adipocytes, tenocytes, and chondroblasts 〚10〛. We recently reported the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells into cardiomyocytes after exposure to 5-azacytidine and the establishment of cell line CMG (cardiomyogenic) that differentiates into cardiomyocytes in vitro 〚11〛. CMG cells exhibit spontaneous beating and express atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), and they may provide a useful and powerful tool for cardiomyocyte transplantation after further characterization of their cardiomyocyte phenotype.

This paper describes the characteristics of bone marrow-derived regenerated cardiomyocytes and discusses the possibility of using them for cardiovascular tissue engineering. The expression and function of adrenergic and muscarinic receptors in CMG cells are also described, because these receptors play a critical role in modulating cardiac function 〚12〛.

2 Does the heart have its own stem cell compartment?

It is well known that skeletal muscle cells contain their own stem cells, called ‘satellite cells’. Satellite cells can both proliferate by cell division and differentiate into skeletal muscle cells, and the differentiated skeletal muscle cells can fuse to form myotubes. By contrast, fetal cardiomyocytes can proliferate by cell division, but they undergo terminal differentiation and stop dividing after birth. A number of studies have reported that cardiomyocytes increase in size by cell hypertrophy, not by cell hyperplasia. To our knowledge, there has been no report of the presence of satellite-cell-like cardiac stem cells in the heart. Beltrami et al. 〚13〛 recently reported that human cardiomyocytes express Ki67, a marker of cell division, and that the M phase of the nucleus of the cardiomyocytes was observed in the border zone area of recent myocardial infarction in autopsied hearts. These findings suggested that only a very few adult cardiomyocytes can divide after the terminal differentiation. Although their findings were very interesting, these cells were insufficient to improve cardiac function, since the population of these cells was very small.

3 Mesenchymal marrow stem cells as a possible source of cardiomyocytes: the cardiomyogenic (CMG) cell?

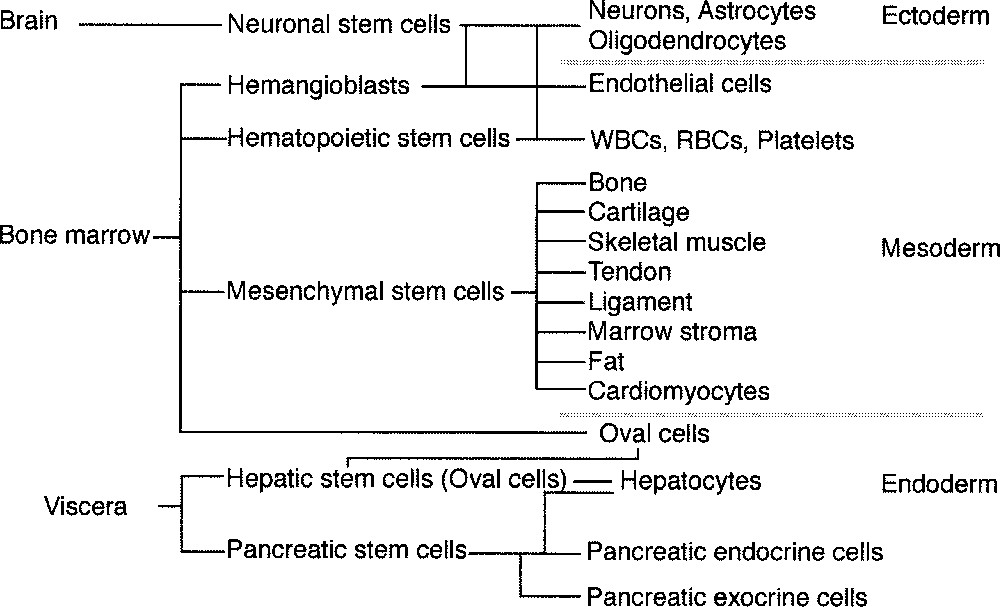

Fig. 1 shows the classification of the stem cell system of adults 〚14〛. Bone marrow stromal cells were previously used as a feeder layer to culture hematopoietic stem cells, and are known to be of mesodermal origin and produce various cytokines and growth factors. In the late 1990s, a number of papers reported that bone marrow stromal cells contain multipotent stem cells for non-hematopoietic tissues, called ‘marrow mesenchymal stem cells’, that could differentiate into osteoblasts, chondroblasts, and adipocytes. All of these cells were known to be of mesodermal origin. If mesenchymal stem cells are multipotent, we hypothesized that they might have the ability to differentiate into cardiomyocytes and instituted this study. We also thought that bone marrow cells could be obtained from patients themselves and that autologous cells would not be rejected after cell transplantation.

Classification of pluripotent stem cells in adult tissues. Bone marrow contains various kinds of stem cells. Mesenchymal stem cells may differentiate into various mesoderm-derived cells, such as osteoblasts, chondroblasts, adipocytes, skeletal muscle cells and possibly cardiomyocytes.

4 Characterization of mesenchymal stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes

4.1 Method of establishing bone-marrow-derived cardiomyocytes

Female C3H/He mice were anesthetized with ether, their femora were excised, and bone marrow cells were collected. The procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines for animal experimentation of the Keio University. Primary culture of the marrow cells was performed according to Dexter’s method. Cells were cultured in Iscove’s modified Dulbecco’s medium (IMDM) supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum and penicillin (100 μg ml–1)/streptomycin (250 ng ml–1)/ amphotericin B at 33 °C in humid air containing 5% CO2. After a series of passages, the attached marrow stromal cells became homogeneous and were devoid of hematopoietic cells. The marrow stromal cells basically did not require co-culture with blood stem cells. Immortalized cells were obtained by frequent subculture for more than four months. Cell lines from different dishes were subcloned by limiting dilution. To induce cell differentiation, cells were treated with 3 μmol l–1 of 5-azacytidine for 24 h. Subclones that included spontaneously beating cells were screened by microscopic observation (first screening), and cells surrounding spontaneous beating cells were subcloned with cloning syringes. Subcloned cells were maintained, exposed to 5-azacytidine again for 24 h, and clones that showed spontaneous beating most frequently were screened (second screening). The clonal cell line thus obtained was named the CMG cell.

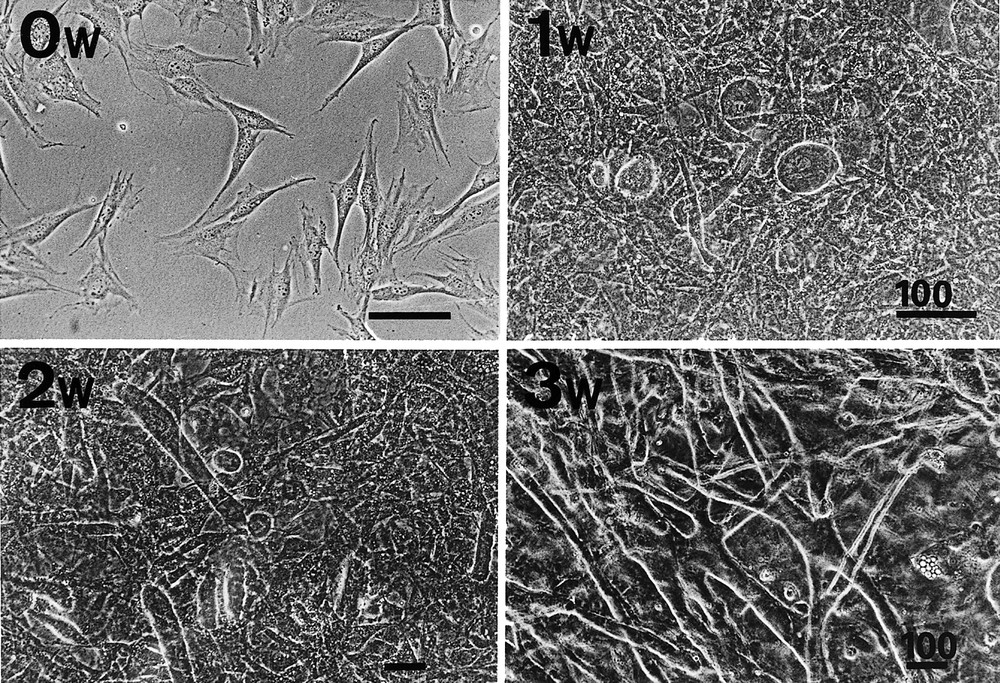

As a result of repeated rounds of limiting dilution, we succeeded in isolating 192 single clones, several of which differentiated into cardiomyocytes and showed spontaneous beating. The experiments were reproducible, but the percentage of cells that differentiated into cardiomyocyte differentiation was specific to each clone. Phase-contrast photography and/or immunostaining with anti-sarcomeric myosin antibodies were used to identify the morphological changes in the CMG cells. CMG cells showed a fibroblast-like morphology before 5-azacytidine treatment (0 week), and this phenotype was retained through repeated subculturing under non-stimulating conditions. After 5-azacytidine treatment, however, the morphology of the cells gradually changed (Fig. 2). Approximately 30% of the CMG cells gradually increased in size at one week, and they formed ball-like appearance, or had lengthened in one direction to exhibit a stick-like morphology. They connected with adjoining cells after two weeks and had formed myotube-like structures at three weeks. The differentiated CMG myotubes maintained the cardiomyocyte phenotype and beat vigorously for at least eight weeks after the final 5-azacytidine treatment and did not de-differentiate 〚11〛. Most of the other non-myocytes had an adipocyte-like appearance.

Phase-contrast photographs of CMG cells before and after 5-azacytidine treatment. Upper left: CMG cells have a fibroblast-like morphology before 5-azacytidine treatment (0 week). Upper right: one week after treatment, some cells gradually increased in size, and developed a ball-like or stick-like appearance (arrows); these cells began spontaneous beating thereafter. Lower left: two weeks after treatment, the ball-like or stick-like cells connected to adjoining cells, and began to form myotube-like structures. Lower right: three weeks after treatment, most of the beating cells were connected and had formed myotube-like structures. Bars indicated 100 μm.

4.2 Regenerated cardiomyocytes display a fetal ventricular phenotype

Various cardiac contractile protein isoforms are differentially expressed in cardiomyocytes at different developmental stages and in different chambers. At around the time of birth there is a developmental switch in the ventricular muscle of small mammals from expression of β-myosin heavy chain (MHC), which is the predominant fetal form, to expression of α-MHC. There is also a developmental switch from expression of α-skeletal actin, which is the predominant fetal and neonatal form, to that of α-cardiac actin, the predominant adult form. We investigated the contractile protein isoforms of bone marrow-derived CMG cells to characterize their phenotype as cardiomyocytes. Table 1 summarizes the results. Fetal, neonatal, and adult ventricle and atrium were used as controls 〚14〛. Expression of both α- and β-MHC was detected in differentiated CMG cells by RT–PCR, but β-MHC expression was overwhelmingly greater than that of α-MHC. CMG cells expressed both α-cardiac and α-skeletal actin, but the α-skeletal actin gene was expressed at markedly higher levels than the α-cardiac actin gene. Interestingly, CMG cells expressed the myosin light chain (MLC)-2v gene, but not the MLC-2a gene. MLC-2v is specifically expressed in ventricular cells, while MLC-2a is specifically expressed in atrial cells. Skeletal muscle cells do not express either α-MHC or MLC-2v. These results indicated that differentiated CMG cells possess the specific phenotype of the fetal ventricular cardiomyocytes 〚11〛.

Isoforms of the contractile proteins in differentiated CMG cells.

| Atrium | Ventricle | CMG | ||||

| Developmental stage | Fetus | Adult | Fetus | Neonate | Adult | |

| α-Actin | skeletal | cardiac | skeletal > cardiac | skeletal | cardiac | skeletal > cardiac |

| Myosin heavy chain | α > β | α | β > α | α > β | α | β > α |

| Myosin light chain | 2a | 2a | 2v | 2v | 2v | 2v |

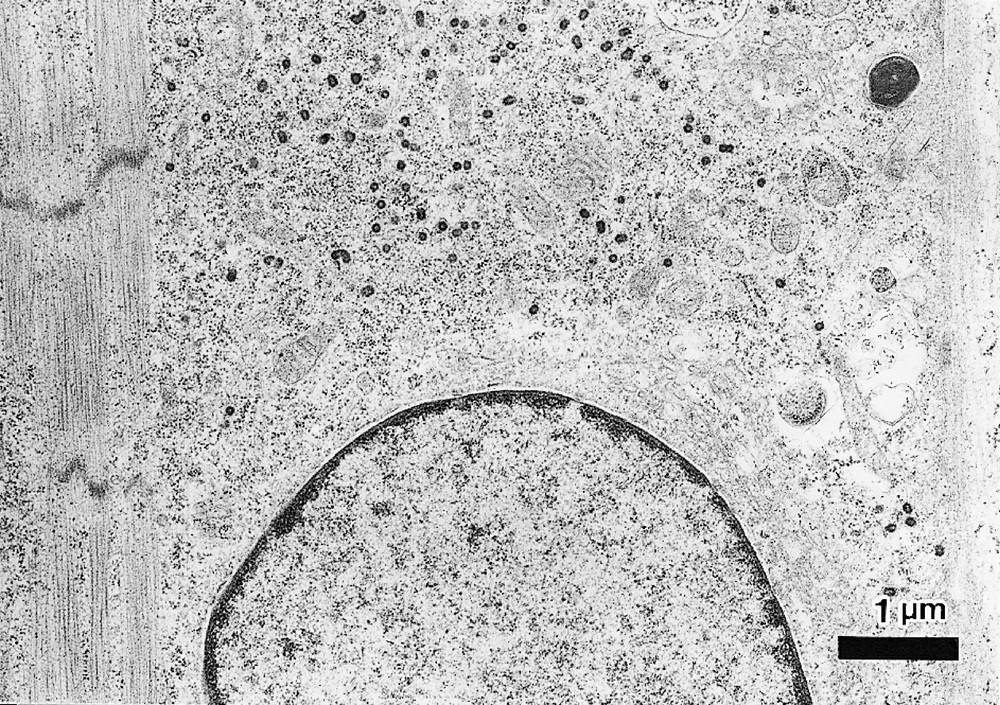

4.3 CMG cells have a cardiomyocyte-like ultrastructure

Representative transmission electron micrographs are shown in Fig. 3. A longitudinal section of the differentiated CMG myotubes clearly revealed the typical striation and pale-staining pattern of the sarcomeres 〚11〛. CMG myotube nuclei were positioned in the center of the cell, not beneath the sarcolemma. The most conspicuous feature of the differentiated CMG myotubes was the presence of membrane-bound dense secretory granules measuring 70–130 nm in diameter. They were thought to be atrial granules, and were especially concentrated in the juxtanuclear cytoplasm, but some were also located near the sarcolemma. These findings indicated that the CMG cells possessed cardiomyocyte-like rather than skeletal muscle ultrastructure.

Transmission electron micrograph of CMG myotubes. A. Differentiated CMG myotubes had well-organized sarcomeres. Abundant glycogen granules and a number of mitochondria were observed. B. Ultrastructural analysis revealed atrial granules measuring 70∼130 nm in diameter in the sarcoplasm, which were especially concentrated in the juxtanuclear cytoplasm. Bar indicates 1 μm.

4.4 Developmental stage of undifferentiated and differentiated CMG cells

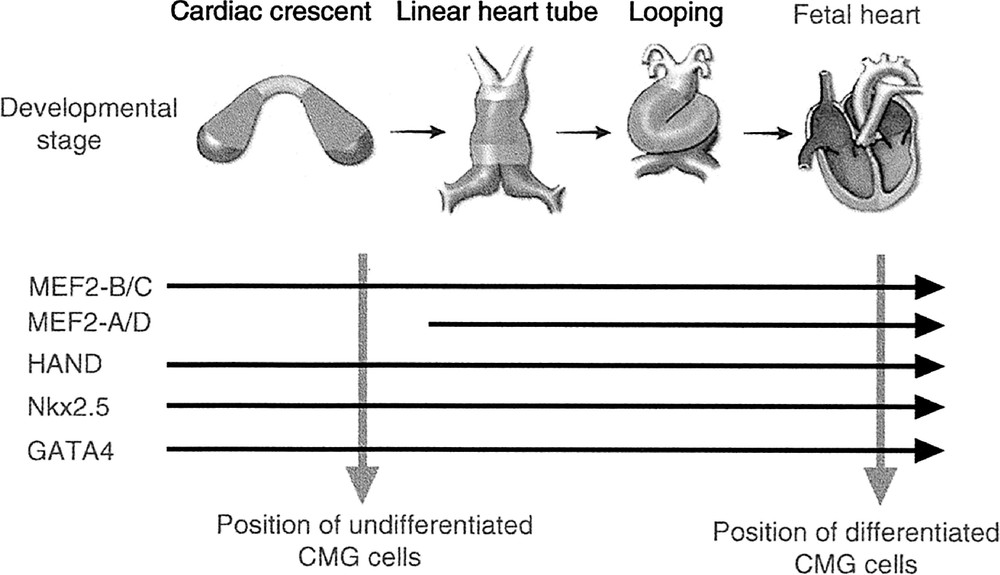

Various cardiac specific transcription factors have been cloned, and their genes are serially expressed in the developing heart during myogenesis and morphogenesis. Fig. 4 shows the time course of the expression of cardiomyocyte-specific transcription factors in fetal developing heart and CMG cells. The genes coding Nkx2.5 〚15〛 (homeobox type transcription factor specifically expressed beginning in the early developing heart), GATA4 〚16〛 (GATA-motif-binding zinc finger-type transcription factor, expressed beginning in the early-stage developing heart), HAND1/2 (basic HLH type transcription factor, expressed in the heart and in the autonomic nervous system), and MEF2-B/C 〚17〛 (muscle enhancement factor: a MADS box family transcription factor expressed in the myocytes) were expressed in the early stage of heart development, and MEF2A and MEF2-D in the middle stage. The CMG cells already expressed GATA4, TEF-1 〚18〛 (transcription enhancement factor 2), Nkx2.5, HAND, and MEF2-C before exposure to 5-azacytidine, and they expressed MEF2-A and MEF2-D after exposure to 5-azacytidine. This pattern of gene expression in CMG cells was similar to that of developing cardiomyocytes in vivo 〚11〛, and indicated that the developmental stage of the undifferentiated CMG cells is close to that of cardiomyoblasts or the early stages of heart development. We estimated that the stage of differentiation of the CMG cells lies between the cardiomyocyte-progenitor stage and the differentiated cardiomyocyte stage.

Expression of cardiac-specific transcription factors in the developing heart and in CMG cells. The horizontal arrows indicate the time course of the expression of cardiac-specific transcription factors in the developing fetal heart. The dotted vertical arrows indicate the expression of these factors in undifferentiated and differentiated CMG cells. CMG cells expressed MEF2-A and MEF2-D after 5-azacytidine exposure, when they acquired a cardiomyocyte phenotype.

4.5 Serial changes in action potential shape in CMG cells simulate those of fetal ventricular cardiomyocytes in vivo

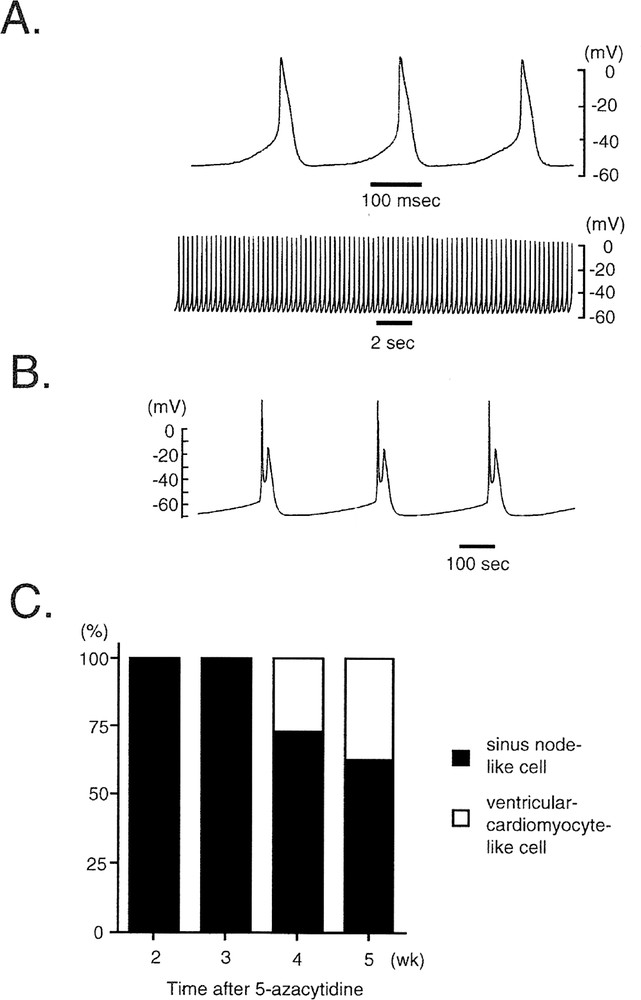

CMG cells exhibit at least two types of distinguishable morphological action potentials: sinus-node-like potentials (Fig. 5A) and ventricular myocyte-like potentials (Fig. 5B) 〚11〛. The cardiomyocyte-like action potential recorded from these spontaneous beating cells is characterized by (1) a relatively long action potential duration or plateau, (2) a relatively shallow resting membrane potential, and (3) a pacemaker-like late diastolic slow depolarization. Peak-and-dome-like morphology was observed in ventricular-myocyte-like cells. Fig. 5C shows the time course of the percentages of the sinus node-like and ventricular myocyte-like action potentials. All action potentials recorded from CMG cells until three weeks were sinus-node-like action potential. The ventricular-myocyte-like action potentials were first recorded after four weeks, and their percentage gradually increased thereafter.

Representative tracing of the action potentials of CMG cells. A, B. Action potential recordings from spontaneous-beating cells were obtained with a conventional microelectrode at day 28 after 5-azacytidine exposure. The action potentials were classified into two groups: (A) sinus-node-like action potentials and (B) ventricular-cardiomyocyte-like action potentials. C. Percentages of CMG cells exhibiting sinus-node-like and ventricular-cardiomyocyte-like action potentials after 5-azacytidine exposure. A ventricular-cardiomyocyte-like action potential was first recorded four weeks after 5-azacytidine exposure, and it rapidly became more prevalent thereafter.

The observation of several distinct patterns of action potential in CMG cells may reflect different developmental stages. Yasui et al. 〚19〛 studied action potentials and the occurrence of one of the pacemaker currents, I(f), by the whole-cell voltage and current-clamp technique at the stage when a regular heartbeat is first established (9.5 days post coitum) and at 1 day before birth. They showed a prominent I(f) in mouse embryonic ventricles in the early stage, and found that it decreased by 82% before birth in tandem with the loss of regular spontaneous activity by the ventricular cells. They concluded that the I(f) current of the sinus-node type is present in early embryonic mouse ventricular cells. Loss of the I(f) current during the second half of embryonic development is associated with a tendency for the ventricle to lose pacemaker potency. Our findings in CMG cells may reflect the developmental changes in the action potentials that occur in embryonic ventricular cardiomyocytes.

4.6 Expression of α1- and β-adrenergic receptor mRNA in CMG cells

4.6.1 Generalities

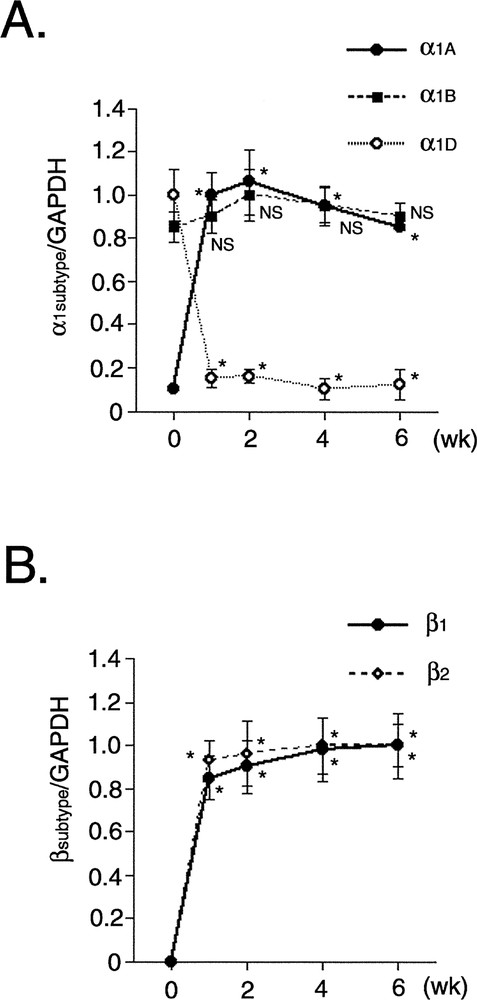

In the heart in vivo, α and β-adrenergic receptors play a key role in modulating cardiac hypertrophy and cardiac function, such as heart rate, contractility, and conduction velocity. CMG cells expressed all the α1 receptor subtypes (α1A, α1B, and α1D) before 5-azacytidine exposure (Fig. 6A) 〚12〛, and their expression in undifferentiated CMG cells may be explained by their ubiquitous or wide expression in vivo 〚20〛. A low level of expression of α1A was observed before 5-azacytidine exposure, and it increased markedly after exposure. Expression of α1B was unaffected by 5-azacytidine. A high level of expression of α1D was detected before 5-azacytidine exposure, but it decreased considerably after exposure. This transcriptional switch may be attributable to the CMG cells having acquired the cardiomyocyte phenotype. The ventricular cardiomyocytes in vivo mainly expressed α1A and α1B, and expressed a low level of α1D receptor. The temporal changes in the expression of α1 adrenergic receptor subtypes in CMG cells are very similar to the postnatal changes observed in neonatal rat heart 〚21, 22〛.

Temporal expression of α1- and β-adrenergic receptor subtype mRNA in CMG cells. A. Densitometric analysis was performed, and the ratio of the RT–PCR product of α1 subtype (α1A, α1B, α1D) receptors to that of GAPDH is shown. Data were obtained from five separate experiments and are shown in arbitrary units compared to the controls. Values are mean ± SE. *: p < 0.01 vs controls (before 5-azacytidine exposure). NS: not significant. B. Densitometric analysis was performed, and the ratio of the RT–PCR product of β subtype (β1 and β2) receptors to that of GAPDH is shown.

The cardiomyocytes of the mammalian hearts express both β1 and β2-adrenergic receptors, the β1 receptor being the predominant subtype (approximately 75–80% of total β receptors) 〚23〛. CMG cells did not express β1 and β2 receptor transcripts before 5-azacytidine exposure, but RT–PCR showed expression of their mRNAs forward day 1 after exposure onward, and exposure, and expression was stable after one week (Fig. 6B) 〚12〛. CMG cells expressed β1 and β2 mRNA after acquiring the cardiomyocyte phenotype. The temporal pattern of expression of these receptors differed from that of α1.

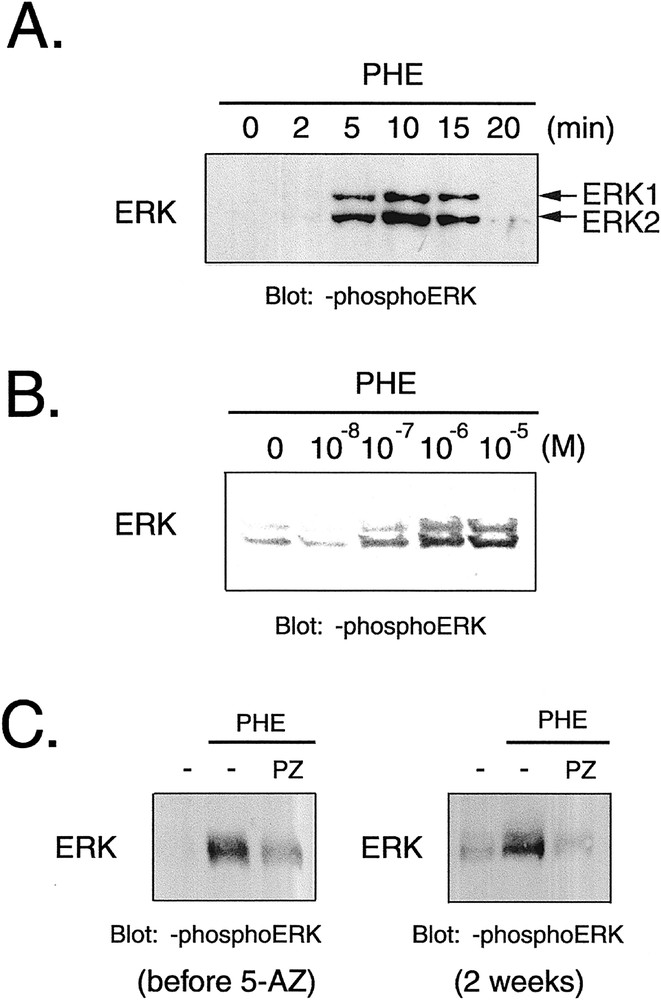

4.6.2 Phenylephrine induces activation of ERK1/2 and hypertrophy in CMG cells via α1 receptors

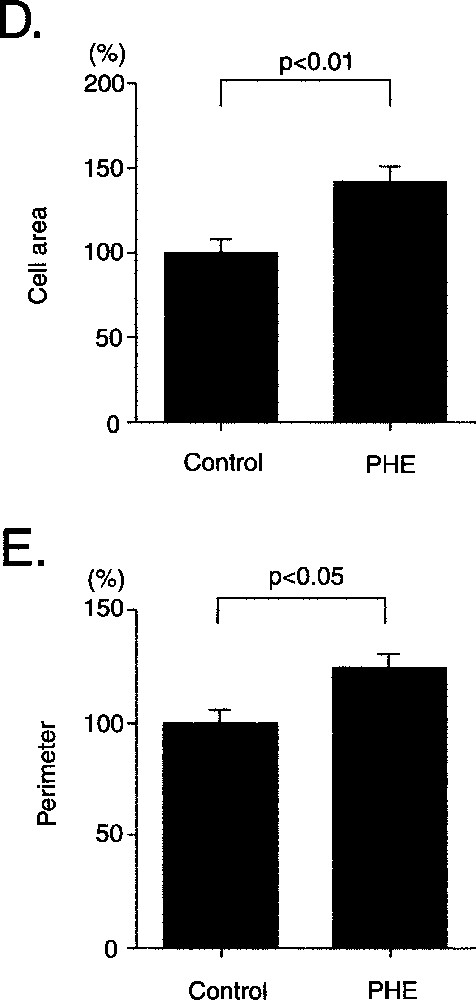

ERK1/2 was activated by phenylephrine, an α1 stimulant, within as little as 5 min, and the activation peaked at 10 min (Figs. 7A and B). The phenylephrine-induced phosphorylation was completely inhibited by prazosin (Fig. 7C), and phenylephrine increased the cell area and the perimeter of the CMG cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7D and E). These findings indicated that CMG cells express functionally active α1-adrenergic receptors 〚12〛.

Effect of phenylephrine on phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and cell size in CMG cells. A–C. (A) Cells at 2 weeks after 5-azacytidine exposure were stimulated with phenylephrine (10–4 mol l–1), and Western blot analysis was performed to detect phosphorylation of ERK1/2. (B) Cells were stimulated with phenylephrine (10–7–10–5 mol l–1) for 10 min, and phosphorylation of ERK was detected. (C) Prazosin (10–6 mol l–1) was added to cells 20 min before stimulation with phenylephrine (10–6 mol l–1). PHE: phenylephrine, PZ: prazosin. D–E. Cells were serum depleted for 24 h, stimulated with phenylephrine for 24 h, and stained with anti-sarcomeric myosin antibody. Cell area (D) and perimeter (E) were quantitated with NIH Image software. (n = 100) *: p < 0.01 vs control.

4.6.3 Isoproterenol increases the cAMP content, spontaneous beating rate, and contractility of CMG cells

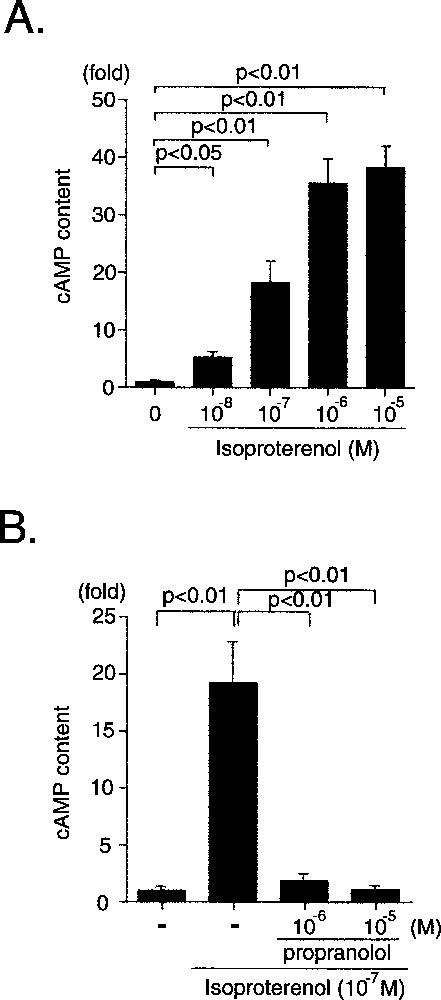

Isoproterenol, a β stimulant, increased the cAMP content of CMG cells, and propranolol completely inhibited the isoproterenol-induced cAMP accumulation (Fig. 8). Isoproterenol was applied to the cells to determine whether it would increase the spontaneous beating rate (Table 2), and the results showed that it increased it significantly to 48% over the rate in the control cells 〚12〛. Pre-incubation with propranolol (non-selective β blocker), CGP20712A (β1-selective blocker) strongly reduced the isoproterenol-induced increase in beating rate, and pre-incubation with ICI118551 (β2-selective blocker) only slightly decreased the beating rate. The increase in beating rate was similar to that of adult murine cardiomyocytes and ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes.

β receptor-mediated cAMP accumulation in CMG cells. A. Effect of isoproterenol on cAMP accumulation in CMG cells at two weeks after 5-azacytidine exposure. B. Cells were pre-incubated with propranolol (10–6 or 10–5 mol l–1) for 20 min and stimulated with isoproterenol (10–7 mol l–1) for 10 min. Data were obtained from five separate experiments and are shown as arbitrary units compared with the controls. *: p < 0.01, **: p < 0.05 vs controls.

Isoproterenol increased the spontaneous beating rate and contractility of CMG cells, mainly via β1 receptors.

| Control | Isoproterenol (10–7 mol l–1) | ||||

| Vehicle | Propranolol (10–7 mol l–1) | CGP20712A (10–7 mol l–1) | ICI118551 (10–7 mol l–1) | ||

| %Increase in beating rate | — | 47.6 ± 8.4* | 10.0 ± 1.9† | 13.8 ± 2.4† | 37.6 ± 1.9‡ |

| Cell motion (μm) | 5.0 ± 0.3 | 6.8 ± 0.7* | 5.6 ± 0.8‡ | 5.3 ± 0.6‡ | ND |

| %Shortening (%) | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.2* | 7.2 ± 0.8‡ | 5.6 ± 0.6‡ | ND |

| Contractile velocity (μm s–1) | 71.1 ± 5.2 | 100.9 ± 11.0* | 71.3 ± 8.8‡ | 70.6 ± 6.6‡ | ND |

We also investigated the effect of isoproterenol on the contractile function of CMG cells and found that it increased cell motion distance, %shortening, and contractile velocity. The isoproterenol-induced increase in contractility was almost completely inhibited by both propranolol and CGP20712A. Collectively, these results indicated that the β1 and β2-adenergic receptors expressed in CMG cells are functional, and that the isoproterenol-induced increase in spontaneous beating rate and contractility is mainly mediated by β1 receptors. The β1 receptor was the predominant subtype that mediated changes in the beating rate in CMG cells, and the beating rate and the contractility were significantly increased by isoproterenol, and completely inhibited by propranolol and CGP20712A. β1-Receptors played a critical role in mediating the isoproterenol-induced signaling in differentiated CMG cells. This expression pattern was consistent with that of cardiomyocytes in vivo.

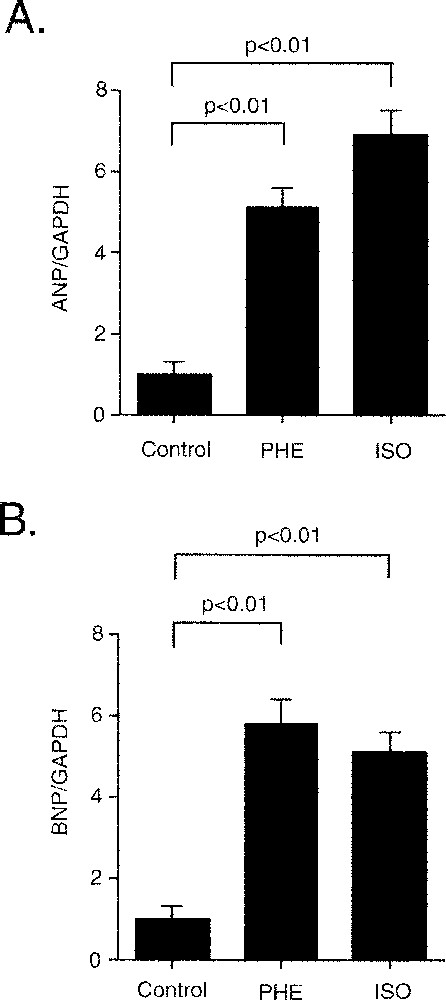

4.6.4 Phenylephrine and isoproterenol induce ANP and BNP mRNA expression

Hypertrophic stimuli are well known to induce reprogramming of gene expression in cardiomyocytes. Phenylephrine and isoproterenol significantly induced expression of the ANP (24 h) gene, and they also induced the BNP (1 h) gene (Fig. 9). These findings demonstrated that α and β adrenergic signal transduction systems in CMG cells are linked to the gene expression that induces cardiac hypertrophy.

Both α and β stimulation induced mRNA expression of ANP and BNP genes. CMG cells were serum depleted for 24 h and pretreated with propranolol and stimulated with phenylephrine (50 μM) or isoproterenol (100 μM). RNA was extracted for 1 h (BNP) and 24 h (ANP), and RT–PCR was examined. All values were normalized to GAPDH. *: p < 0.01 vs controls.

4.7 CMG cells express muscarinic receptor mRNA after 5-azacytidine exposure

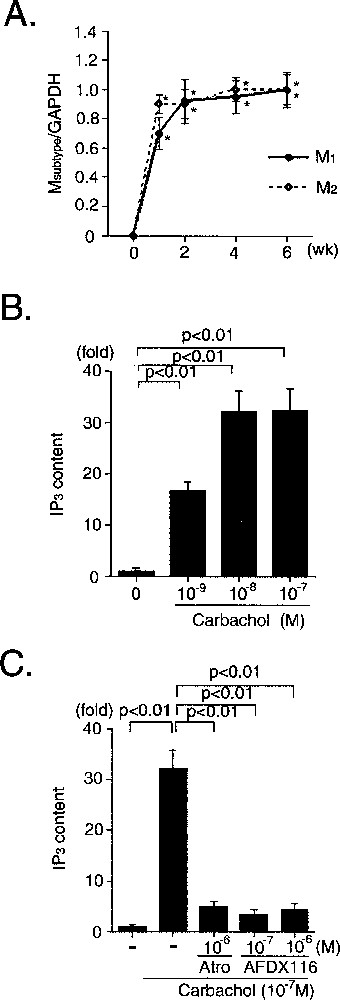

Heart rate, conduction velocity, and contractility were negatively regulated by the parasympathetic nervous system in cardiomyocytes, and muscarinic (cholinergic) receptors play an important role in mediating this function. To date, 5 subtypes (M1–M5) of muscarinic receptors have been cloned. The expression of the muscarinic receptors is tissue-specific, and cardiomyocytes mainly express M2 receptors in the mouse and human 〚24〛. The M1 receptor subtype is also expressed in murine neonatal and adult cardiomyocytes. Fig. 10A shows the temporal expression pattern of M1 and M2 receptor mRNA. Neither receptor was detected prior to 5-azacytidine exposure. CMG cells began to express these receptors when they acquired the cardiomyocyte phenotype.

Expression and function of M1- and M2-muscarinic receptors in CMG cells. A. The ratio of the RT–PCR product of muscarinic subtype to that of GAPDH is shown. Data were obtained from five separate experiments and are shown as arbitrary units over controls. *: p < 0.01 vs controls. B. Effect of carbachol on IP3 production in CMG cells, two weeks after 5-azacytidine exposure. C. Effect of atropine (10–6 mol l–1) and AFDX116 (10–7 or 10–6 mol l–1) on carbachol-induced IP3 production. Data were obtained from five separate experiments and are shown as arbitrary units compared with the controls. *: p < 0.01 vs controls. Atro: atropine.

M1 receptors coupled to Gq/G11 and activated phospholipase Cβ via Gqα, leading to IP3 production, and M2 receptors coupled to Gi/G0/Gz and activated phospholipase Cβ via Giβγ, leading to IP3 production 〚25, 26〛. Carbachol, an acetylcholine homologue, increased the content of a second messenger, IP3 (inositol triphosphate), in CMG cells (Fig. 10B), and pre-incubation with atropine (non-selective muscarinic blocker) and AFDX116 (M2-selective blocker) inhibited the carbachol-induced IP3 production (Fig. 10C). These findings indicated that muscarinic receptors can transduce their signals, and that M2 receptors play a critical role in this carbachol-induced IP3 production in CMG cells. This expression pattern is similar to that of cardiomyocytes in vivo.

4.8 Significance of expression of adrenergic and muscarinic receptors in CMG cells

Cardiomyocytes in vivo respond to stimulation by both sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, and such stimulation alters the heart rate, conduction velocity, and contractility, enabling the cells to adapt to rapid changes in systemic oxygen demand. To date, and to our knowledge, ES cells and mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived CMG cells are the only possible candidates for regeneration of cardiomyocytes. We have already transplanted these cells into normal adult mouse hearts, and have observed that transplanted cells survived in recipient hearts for at least several weeks. Regenerated cardiomyocytes must express functional adrenergic and muscarinic receptors to be useful for transplantation, although we did not investigate all signaling pathways and their functions. CMG cells are potential candidates for cardiomyocyte cell transplantation, because they possess such receptors.

5 Cell transplantation therapy for the treatment of heart failure

We have already transplanted CMG cells into normal adult mouse hearts, and observed that the transplanted cells could survive in the recipient heart for at least several months. Fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and skeletal muscle cells were the first cells used for transplantation into scar tissue secondary to experimental myocardial infarction in the heart in vivo. While transplantation of these cells into scar tissue might improve cardiac remodeling or diastolic function, it is unlikely to improve systolic function. Transplantation of cardiomyocytes, however, might rescue systolic function. The only potential sources of regenerated cardiomyocytes available to date are embryonic stem (ES) cells and mesenchymal stem cells. ES cells differentiate into cardiomyocytes in vitro and have both advantages and disadvantages for cardiomyocyte regeneration. Transplanted ES cells may form teratomas if some undifferentiated totipotent cells are still present, and recipients must take immunosuppressants, because ES cells are allogeneic. By contrast, since mesenchymal stem cells do not carry any inherent risks of tumor formation and are syngeneic, it is reasonable to use autologous mesenchymal stem cells to treat heart disease. Nevertheless, there is a need to improve both the current methods for identification and culture of mesenchymal stem cells, and for induction of CMG cell differentiation, which are still inefficient and slow. Identification of specific growth factors, cytokines, or extracellular matrix factors that regulate cardiomyocyte differentiation may help to accelerate this process faster and make it more efficient.

6 In vivo evidence that marrow cells can generate functional cardiac tissues

Recent studies have revealed that bone-marrow-derived cells differentiate into various types of cells in vivo. Shimizu et al. reported that smooth-muscle-like cells (SMCs) in graft-vs-host arterial lesions could arise from circulating bone-marrow-derived precursors. They used murine aortic transplants to formally identify the source of SMCs in lesions in grafted arteries 〚27〛. Allografts in beta-galactosidase transgenic recipients showed that intimal SMCs arose almost exclusively from host cells, and bone-marrow transplantation of beta-galactosidase-expressing cells into aortic allograft recipients demonstrated that the intimal cells included those of marrow origin.

Kocher et al. 〚28〛 showed that bone marrow from adult humans contains endothelial precursors with phenotypic and functional characteristics of embryonic hemangioblasts and that they can be used to directly induce new blood vessel formation in the infarct-bed (vasculogenesis) and proliferation of preexisting vasculature (angiogenesis) after experimental myocardial infarction. The neoangiogenesis resulted in decreased apoptosis of hypertrophied myocytes in the peri-infarct region, long-term salvage and survival of viable myocardium, reduction in collagen deposition, and sustained improvement in cardiac function.

We also observed that transplanted bone marrow cells differentiated into cardiomyocytes in the recipient heart in vivo (unpublished observation). These findings provided direct evidence that bone marrow cells can regenerate various types of cells in cardiac tissue. We expect cardiac tissues damaged by myocardial infarction or other diseases to be repaired by bone-marrow-derived stem cells in the near future, and the precise mechanism should be investigated to achieve this goal.