1 Introduction

Sounds consist of pressure changes that propagate through the air. Most of the sounds in which we are interested, especially speech and music, involve primarily sinusoidal oscillations in air pressure at one or several frequencies. These sounds are produced by regular vibrations of an ensemble of oscillators, such as human vocal cords or the strings of a piano. The complex qualities that we perceive in particular sounds – the personality of a voice or the coloration of a musical instrument – stem from the admixture of numerous pure tones.

In order that we may hear and recognize sounds, our ears must capture airborne acoustical energy and transduce it into electrical signals that can be processed by the brain. While doing so, each ear must also decompose sounds into their constituent frequencies and analyze each independently. The pure, sinusoidal components of a complex sound constitute the elements of a fingerprint that allow the sound to be identified. The ear must therefore undo the work of the vocal apparatus or piano, separating the individual tones that were combined as the sound was produced.

How might sounds be captured and resolved? The familiar phenomenon of sympathetic resonance provides a clue. When a loud sound continues for some time, we may notice that certain objects tuned to the frequencies in that sound begin to vibrate. The noise of a passing airplane or train, for example, rattles particular windows. Specific strings in the backplane of a piano likewise resonate sympathetically when music is played by other instruments. A similar principle operates on a microscopic scale in the inner ear [1]. Within the snail-shaped receptor organ for hearing, the cochlea, lies a narrow, elastic, 35-mm-long strip of connective tissue called the basilar membrane. Each increment of this membrane acts as a tiny resonator: because of its mass and tension, a given segment vibrates sympathetically in response to stimuli of one specific frequency. Because the basilar membrane's mass and tension vary continuously along its length, all audible frequencies are represented in an orderly pattern, or tonotopic array, along the membrane. At the apex of the cochlear spiral resides sensitivity to the lowest sounds that we can detect, with frequencies near 20 Hz. The cochlear base represents the highest audible tones, with frequencies up to 20 kHz.

Although the resonant properties of the basilar membrane potentially provide a solution to the problem of detecting sound and resolving its component frequencies, an enigma persists: how can the basilar membrane resonate while immersed in liquid? Because the cochlea is filled with aqueous solutions, the moving basilar membrane inevitably experiences the damping effect of viscous drag from the surrounding fluids [2]. Asking the basilar membrane to oscillate under these conditions is like requiring a tuning fork to vibrate in honey! Researchers were unable for decades to account for the ear's demonstrable success in detecting and resolving sounds in the presence of such severe damping.

We now recognize that the ear accomplishes its task by amplifying its mechanical inputs (reviewed in [3–6]). Although fluid damping continuously drains energy from sound stimuli, the receptor cells of the ear – hair cells – counter this loss by active movements that accentuate the inputs. When our ears are operating normally, the activity of hair cells increases our auditory sensitivity by more than one-hundredfold. So vigorous is the amplification that, in a silent environment, the great majority of human ears are even capable of emitting sounds! After providing a brief review of the operation of hair cells, this article examines one mechanism by which these cells enhance the sensitivity of hearing.

2 Mechanoelectrical transduction by the hair cell

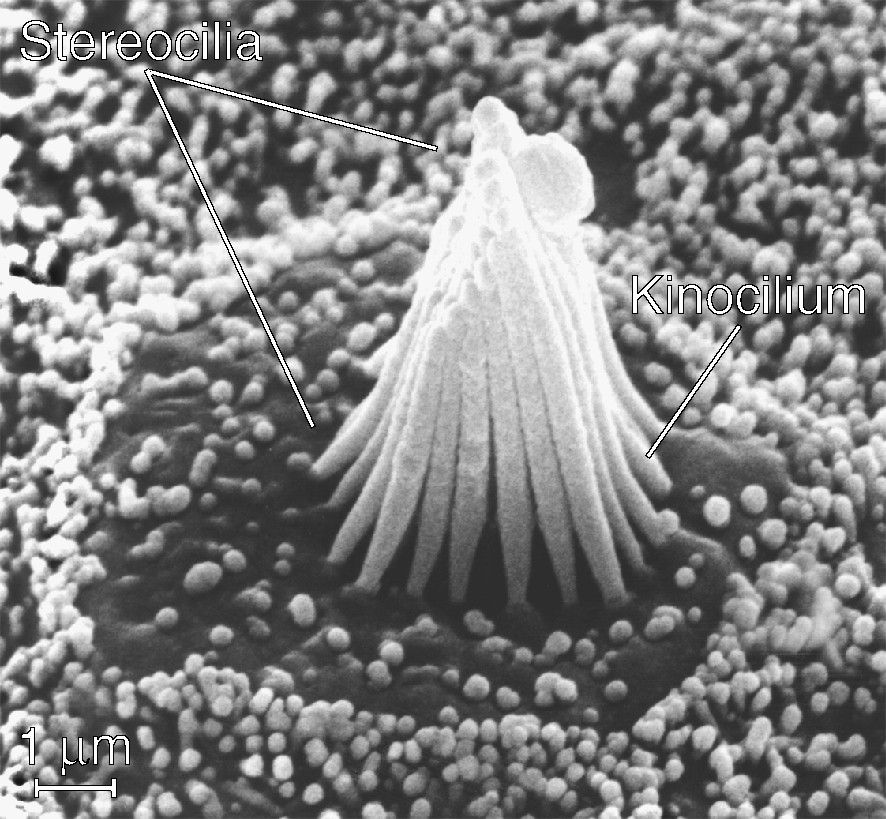

A hair cell uses an unusually complex mechanical apparatus, the hair bundle, to conduct an unusually simple transduction process [7]. Whether dedicated to the detection of sound in the cochlea, of acceleration in the vestibular labyrinth, or of water movement in the lateral-line organ, every hair cell possesses a similar hair bundle. This structure comprises 20–300 processes termed stereocilia, each a rigid cylinder of crosslinked actin filaments ensheathed by plasmalemma, projecting almost perpendicularly from the apical cellular surface (Fig. 1). Because the stereocilia vary in length from one edge of a hair bundle to that opposite, a bundle resembles a stand of organ pipes or the beveled tip of a hypodermic needle. Centered at the bundle's tall edge is a single true cilium, the kinocilium, with a array of microtubules at its core.

A scanning electron micrograph of a typical hair bundle. Projecting from the apical surface of a hair cell in the bullfrog's sacculus, this bundle comprises a hexagonal array of about 50 stereocilia whose lengths increase from the left to the right edge. Because they are most flexible at their tapered basal insertions, individual stereocilia pivot there when the hair bundle is deflected. The single kinocilium, which stands at the center of the bundle's tall edge, bears a bulbous swelling at its tip. Stubby microvilli dot the apical surface of the hair cell and cover the supporting cells surrounding it.

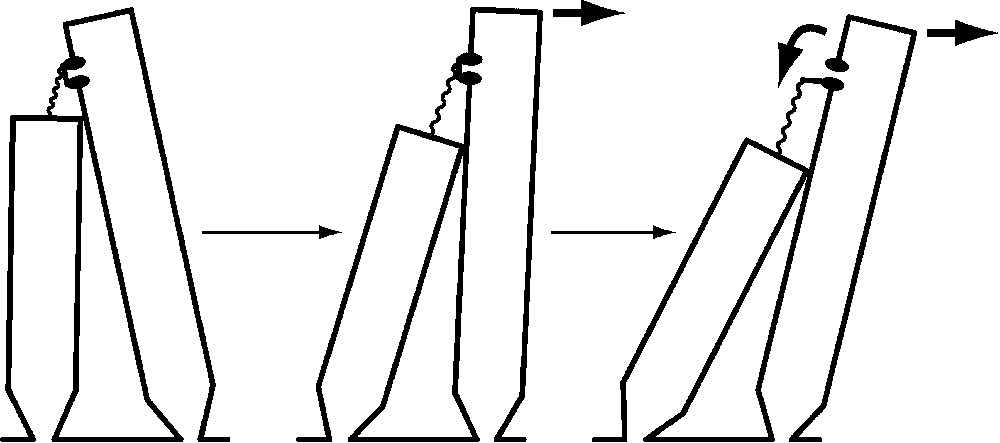

The hair bundle's broken symmetry is key to its function. At the tip of each stereocilium except those in the tallest rank, a molecular filament – or more probably a braid of two or three filaments – extends obliquely upward to an insertion on the side of the longest contiguous stereocilium. Tension in these elastic tip links pulls the stereociliary tips together. When the hair bundle is deflected towards its tall edge, which is defined as a positive stimulus, the shearing motion between adjacent stereocilia increases the tension in each tip link (Fig. 2). It is thought that one or a few transduction channels are attached to a tip link's end; the increase in tip-link tension opens these channels, allowing an influx of K+ and Ca2+ and consequently causing a cellular depolarization. Movement of the hair bundle in the opposite direction, towards its short edge, reduces tip-link tension, closes the 10–20% of the channels open at rest, and yields a hyperpolarization.

The mechanoelectrical transduction process of a hair cell. A few transduction channels (of which one is portrayed) occur at one or both ends of each tip link, an elastic strand connecting the tip of one stereocilium to the side of the longest adjacent process. At rest (left), most channels are closed. Application of a stimulus force (arrow at top of bundle) deflects the bundle in the positive direction (center), increasing the tension in the tip link. This tension promotes channel opening (right), permitting cations to flow through the nonselective ion channel into the stereociliary cytoplasm. When the channel opens, reduction in the tension borne by the tip link also allows the bundle to move still farther. Note that the bundle movements are greatly exaggerated: even a deflection one-twentieth as large as that diagrammed would saturate the cell's response.

The direct nature of the mechanoelectrical transduction process in hair cells explains three key features of the cells' responsiveness. First, transduction is exceptionally rapid [8,9]. Because no chemical processes intervene between the application of a stimulus and the opening of transduction channels, the electrical response commences within microseconds. This rapidity of responsiveness allows humans to hear frequencies as great as 20 kHz and permits bats and whales to detect signals at 100 kHz or still higher. A second feature of the hair cell's transduction process is its sensitivity. At our auditory threshold, the faintest sounds that we can hear produce vibrations within the ear estimated at only [10]. Our ability to detect movements of such atomic dimensions implies that transduction has no strict threshold; instead, an arbitrarily small signal may eventually be detected by neural averaging over many cycles.

The third and most surprising aspect of the ear's transduction process is that it distorts our hearing. As long ago as 1714, the Italian violinist Tartini observed auditory distortion products [11,12]. While sounding on his instrument two pure notes, of frequencies and , he was surprised to hear as well tones at frequencies of , , , , and so on. So prominent are these combination tones that they have subsequently been used in musical compositions. In certain compositions by Stockhausen, for example, the melody is played by no instrument, but is synthesized within the listener's ears from combinations of the tones that are actually sounded. Distortion products arise from the mechanical properties of individual hair bundles. During half of each cycle of bundle oscillation, the opening of transduction channels withdraws energy from the mechanical stimulus. This energy is then restored in the opposite half-cycle, as the channels reclose. The asymmetrical ebb and flow of energy, which can actually be measured [13], implies that the hair bundle's stiffness varies during each cycle of oscillation. Just as nonlinearity in an amplifier or speaker distorts the sound produced by a stereo system, so a hair bundle's mechanical nonlinearity underlies the production of distortion products [14].

3 Mechanical properties of the hair bundle

To measure the mechanical properties and movements of a hair bundle, an investigator first dissects a receptor organ from the ear of an experimental animal. Bathed in artificial saline solutions that mimic the normal milieu of the ear, the organ is positioned on the stage of a light microscope and examined with differential-interference-contrast optics. After enzymatic removal of accessory structures overlying the sensory epithelium, the exposed hair bundles may be observed readily. A fine glass fiber, less than 100 μm in length and under 1 μm in diameter, is positioned horizontally adjacent to a selected bundle and the fiber's tip is attached near the bundle's top (Fig. 3A). A highly magnified image of the fiber's tip is then focused onto a sensitive photodiode, whose electrical output represents hair-bundle motion with a spatial resolution of less than 1 nm and a frequency response exceeding 1 kHz. The fiber attached to a hair bundle also provides a convenient means of stimulating the mechanoreceptive organelle. If the base of the fiber is moved by a piezoelectrical stimulator, the fiber's tip deflects the bundle. Flexion of the calibrated glass fiber then provides the experimenter with an index of the restoring force produced by the bundle, and thus a means of measuring the bundle's stiffness.

Mechanical properties of a hair bundle. (A) A bundle's movement is measured by attaching the tip of a fine glass fiber to the kinociliary bulb near the bundle's top (left). An image of the fiber's tip is magnified one-thousandfold and projected onto a dual photodiode, whose electrical output provides a measure of bundle displacement. While the base of the fiber remains at rest (right), the movement of its tip reflects spontaneous hair-bundle motion. During stimulation, the base of the fiber is offset by a distance with two consequences: the bundle is deflected by a distance X, and the flexible fiber is bent in the opposite direction by a distance . If the stiffness of the fiber at its tip is KSF, then the force applied to the hair bundle is . (B) A displacement-force relation plots the force that must be applied by a stimulus fiber to move the hair bundle by various distances. The slope of the relation, which has been fitted with the smooth curve expected on theoretical grounds, reflects the bundle's stiffness. For large deflections in either direction, the stiffness is positive and roughly constant. Over a distance of about ±10 nm from the origin, however, the slope is negative. As a consequence, the hair bundle cannot reside stably in the central part of its range. The variable stiffness of the bundle also constitutes the nonlinearity responsible for the generation of auditory distortion products.

During the application of mechanical force, a passive object is ordinarily deflected by a distance proportional to the force. This linear relationship – Hooke's Law – applies as well to the hair bundle of an inert or dead hair cell. For such a passive object, the slope of the relation between displacement and force, the object's stiffness, is constant. When the mechanical properties of an active, spontaneously oscillating bundle are measured, however, a remarkable property emerges [15]: the bundle displays a region of negative stiffness (Fig. 3B). To position the hair bundle anywhere within a range of roughly about the center of the displacement-force relation, the stimulus fiber must actually push the bundle in the opposite direction! This behavior implies that a hair bundle is dynamically unstable; without the imposition of an external force such as that from the stimulus fiber, the bundle cannot reside in the region of negative stiffness. Instead, it must move in either the positive or the negative direction until it reaches one of the two points at which there is no force acting on the bundle and its stiffness is positive. As will be seen below, the hair bundle's instability plays a key role in its capacity to amplify mechanical signals.

4 An amplifier in the hair bundle

In the absence of stimulation, a hair bundle from the frog's sacculus, a receptor for low-frequency ground vibration and sound, oscillates at frequencies of 5–40 Hz (Fig. 4). Typically somewhat larger than 20 nm in peak-to-peak magnitude, the oscillations are irregular in two ways. First, their frequency varies from cycle to cycle. And second, the waveform of the bundle oscillations is asymmetrical. Especially in the instance of relatively slow oscillations, each half-cycle of motion may be seen to comprise a rapid stroke followed by a slower movement in the same direction. Spontaneous oscillations constitute a striking demonstration of the hair bundle's ability to do work [16], for the movements clearly exceed those that would be expected as a result of Brownian motion [17]. Unprovoked bundle oscillations may also underlie the production of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions, the sounds emanating from the ears of many species, including ours, in a quiet environment (reviewed in [5,6,18]).

Spontaneous and evoked mechanical activity of a hair bundle. The upper trace depicts hair-bundle motion, as measured with the photodiode system, whereas the lower trace represents movement of the stimulus fiber's base. In the absence of stimulation, at the outset of the record, this frog's saccular hair bundle displays spontaneous oscillations characterized by variations in frequency and amplitude. When a sinusoidal displacement is applied at the base of the attached stimulus fiber, the bundle's movement is entrained: the oscillations are phase-locked to the stimulus and become more regular in magnitude. Because the amplitude of bundle motion is about twice that of the stimulus, the hair bundle must be amplifying its mechanical input.

When stimulated at a frequency near that of its spontaneous oscillation, a hair bundle becomes entrained [19]: the bundle follows the fiber's oscillations on a one-to-one basis and at a constant phase with respect to the stimulus (Fig. 4). If the stimulus frequency exceeds that of the bundle's spontaneous oscillation, the bundle's movement is accelerated by the input, and the phase of the response lags that of the stimulus. If the stimulus frequency is lower, by contrast, the bundle's movement is slowed, and the phase of the response leads that of the stimulus. Most remarkably, when a small stimulus is applied, the amplitude of bundle motion exceeds that of the fiber's base movement. This result implies that the bundle is conducting amplification, for the energy in the system's output – bundle motion – exceeds that in the input – fiber-base movement [20].

What cellular motor drives spontaneous hair-bundle motion and powers the amplification of mechanical stimuli? Experiments suggest that two active processes contribute to the bundle's movement. First, a hair bundle possesses an ensemble of myosin-based adaptation motors that reset the bundle's position of mechanosensitivity after large, continued displacements [21] (reviewed in [22–25]). Small clusters of myosin Ic (formerly termed myosin Iβ) molecules, which congregate at the upper insertions of the tip links [26–28], work to maintain enough tension in the links that the transduction channels are always poised to open. As these adaptation motors attempt to position the hair bundle in its region of negative stiffness, the bundle oscillates back-and-forth [15].

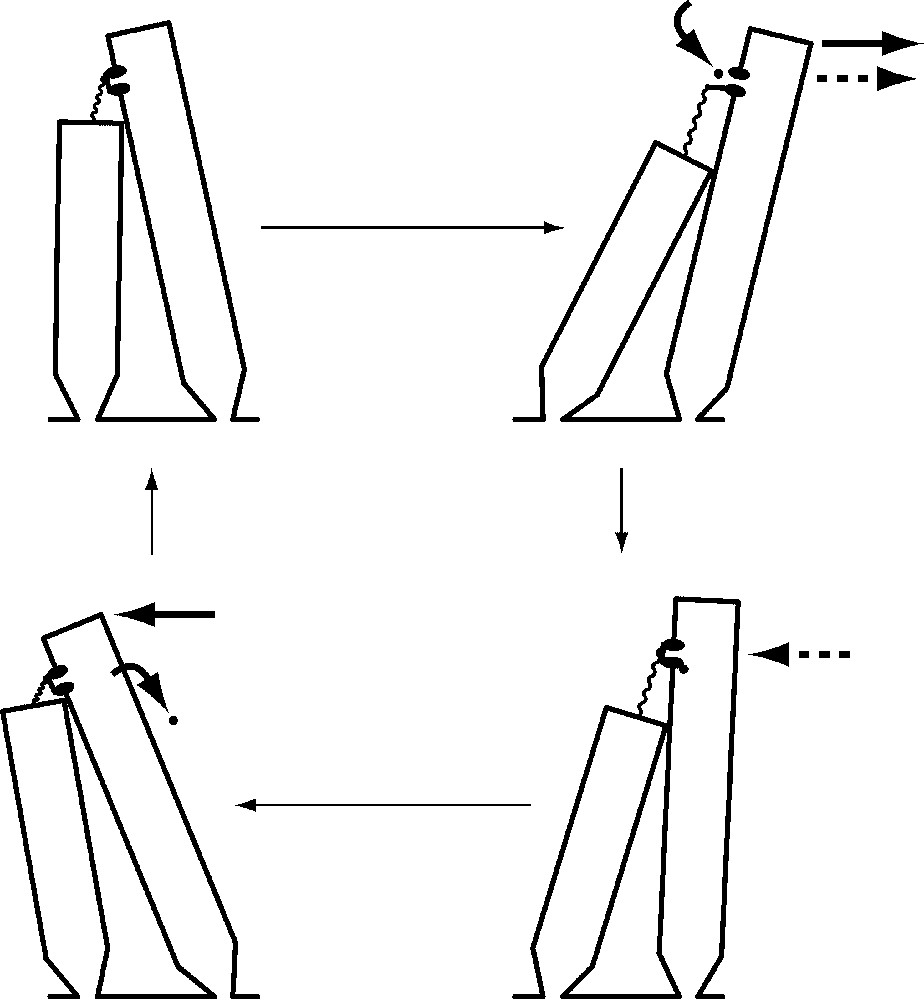

The second source of active force in hair bundles is the transduction channels themselves. When abruptly pushed in the positive direction by a stimulus fiber, a bundle first moves in the direction of stimulation, then abruptly jumps back in the opposite direction [13]. This retrograde movement, or ‘twitch’, is associated with reclosure of the transduction channels initially opened by the stimulus [29]. Because the speed and magnitude of the twitch increase when the extracellular Ca2+ concentration is raised [30,31], it is thought that Ca2+ enters the stereocilia through open transduction channels, binds to regulatory sites associated with the channels' cytoplasmic surface, and causes the channels' reclosure (Fig. 5). This in turn increases tip-link tension, pulling the stereociliary tips together and jerking the bundle in the negative direction. After unbinding some time later, the Ca2+ is pumped from the cell by Ca2+-ATPase molecules that occur at a high density in the stereociliary plasmalemma [32]. This form of hair-bundle movement is therefore powered by the transmembrane Ca2+ gradient and ultimately by the ATP consumed by Ca2+ pumps.

Mechanical amplification by Ca2+-dependent reclosure of transduction channels. A cycle of oscillation begins with a quiescent hair bundle (top left) with most of its transduction channels closed. When the bundle is deflected by the positive phase of a sinusoidal stimulus (top right, solid arrow at top), channel opening permits an influx of cations and thereby initiates the cell's electrical response. Relaxation of the tip link also promotes additional bundle movement in the positive direction (dashed arrow). The binding of Ca2+ to an internal site associated with the channel (bottom right) closes the channel; by increasing tip-link tension, this produces a force that pulls the bundle back in the negative direction (dashed arrow). As the negatively directed phase of the stimulus continues the negative bundle movement (bottom left, solid arrow at top), Ca2+ unbinds from the channel and is pumped from the cell by Ca2+-ATPase. The bundle is then poised to repeat the cycle of motion.

Mathematical modeling confirms the potential effectiveness of Ca2+-mediated channel reclosure in mechanical amplification. With appropriate choices of the parameter values for hair-bundle stiffness and for the rates of channel gating and Ca2+ binding, a model readily produces bundle oscillations over the frequency range of human hearing [33]. Moreover, the mathematical analysis confirms that hair-bundle oscillation produced by this mechanism is highly tuned and can effect amplification by more than one-hundredfold. Each hair cell probably poises itself near a dynamical instability, the Hopf bifurcation, where amplification and frequency selectivity are optimal [34,35].

The relative contributions of the two forms of active hair-bundle motility remain unknown. Although myosin-based bundle movement underlies amplification at low frequencies by hair cells of the frog's sacculus [15,20], this mechanism may be incapable of operating in the upper reaches of the auditory frequency range (reviewed in [36]). Stretch-activated insect flight muscle can oscillate at frequencies of several kilohertz, however, so it is not inconceivable that a myosin-based bundle motor can contribute to high-frequency amplification (reviewed in [22]). Ca2+-mediated channel reclosure potentially is able to operate at very great frequencies, for each of its constituent steps – channel opening, Ca2+ entry, Ca2+ binding, channel reclosure, Ca2+ unbinding, and Ca2+ diffusion from the binding site – can be accomplished in no more than a few tens of microseconds [33].

5 Conclusion

In the interest of fast, sensitive hearing, evolution evidently has accepted a mechanoelectrical transduction process with an inherent flaw, the nonlinearity that distorts our hearing. More impressively, the ear has harnessed this nonlinearity to energy sources, myosin-based adaptation and Ca2+-dependent channel reclosure, to produce an effective amplifier of acoustical energy. Active hair-bundle motility appears to be the dominant source of amplification in the internal ears of amphibians and reptiles, and probably in those of fishes and birds as well. It remains to be seen whether this remarkable active process also heightens auditory sensitivity in mammals, including ourselves.

Acknowledgments

An investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the author thanks D. Bozovic, D. Chan, and L. Le Goff for comments on the manuscript, R.A. Jacobs and P. Martin for the experimental data reproduced in the figures, and National Institutes of Health grant DC00241 for support.