Version française abrégée

Réputés pour leur très grande diversité, aussi bien dans les milieux désertiques que dans les forêts humides [1,2], les scorpions sont également présents dans la plupart des autres habitats terrestres, à l'exception cependant de la toundra, de la taïga des hautes latitudes et de la majorité des biotopes d'altitude élevée [1]. Ils sont absents des zones boréales, mais quelques espèces peuvent se trouver dans des régions de haute latitude de l'hémisphère sud, où les conditions climatiques sont sévères. Un exemple en est fourni par Bothriurus patagonicus Maury, 1968, espèce qui vit en Patagonie, dans l'Extrême-Sud de l'Argentine [3]. Certaines espèces existent dans les montagnes ou dans les habitats alpins, mais, hors des régions tropicales et subtropicales, là où les conditions climatiques sont sévères, elles sont rares, et appartiennent à un nombre limité de groupes génériques et familiaux. Des espèces de la famille des Euscorpiidae, du genre Euscorpius Thorell, 1876, parviennent jusqu'à 2000 m dans les Alpes [1,4], et celles des familles des Diplocentridae et Vaejovidae, des genres Diplocentrus Peters, 1861 et Vaejovis C.L. Koch, 1836, jusqu'à 3000 m en Amérique du Nord [1,5,6]. Dans les Himalayas de l'Inde, du Pakistan, du Népal et du Tibet, des espèces des familles Buthidae, Chaerilidae et Scorpiopidae ont été trouvées jusqu'à 4500 m. Elles concernent des genres tels Hottentotta Birula, 1908, Chaerilus Simon, 1877 et Scorpiops Peters, 1861 [1,7–10]. Le record d'altitude pour une espèce de scorpion appartient cependant à un Bothriuridae d'Amérique du Sud, Orobothriurus crassimanus Maury, 1975, qui a été collecté à 5560 m dans le Nevado de Huascaran, dans les Andes péruviennes [11].

Les scorpions de la famille des Liochelidae sont pratiquement absents des régions montagneuses. Cette famille est répartie dans tous les continents, à l'exception de l'Amérique du Nord. Elle est composée de huit genres, distribués dans les îles de l'océan Pacifique, le Nord de l'Australie, l'Asie, les îles de l'océan Indien (Maurice, Seychelles et Madagascar), le Sud et l'Ouest de l'Afrique, les Amériques du Sud et centrale, ainsi que dans les Antilles. Seulement deux espèces du genre Opisthacanthus Peters, 1861, ont été trouvées dans des montagnes de moyenne altitude : Opisthacanthus weyrauchi Mello-Leitão, 1948 vit jusqu'à 1800 m dans la Puna des Andes péruviennes, et Opisthacanthus rugulosus Pocock, 1896 jusqu'à 2350 m dans les montagnes du Malawi [15,16].

La découverte d'un nouveau genre et d'une nouvelle espèce de scorpion Liochelidae dans l'Himalaya du Tibet a un double intérêt : (i) le nouveau scorpion est le premier élément de la famille des Liochelidae collecté en dehors des régions tropicales et subtropicales, qui sont typiques de la répartition de cette famille ; (ii) il est le premier élément de la famille trouvé dans des hautes montagnes où les conditions climatiques sont sévères, voire extrêmes.

Le nouveau genre et la nouvelle espèce constituent très probablement un élément isolé de la famille des Liochelidae, qui aurait comme ancêtre un proto-élément déjà présent sur la plaque indienne lors de sa migration vers l'hémisphère nord. Le choc entre la plaque indienne et le continent asiatique, et le soulèvement de l'Himalaya qui en a résulté, ont très certainement isolé divers éléments des basses terres de l'Inde, qui ont pu, par la suite, s'adapter aux conditions des montagnes de moyenne et haute altitude.

1 Introduction

Although scorpions are most diverse in deserts, arid formations and rain forests [1,2], they also occur in the majority of the other terrestrial habitats, with the exception of tundra, high-latitude taiga, and high mountain tops [1]. Scorpions are absent from boreal areas, but some are to be found in high-latitude regions of the Southern Hemisphere, where climatic conditions may be very severe. This is the case with Bothriurus patagonicus Maury, 1968, a species that occurs in Patagonia in the extreme South of Argentina [3]. Some species can be found in mountain and alpine habitats, but those living in montane sites outside tropical or subtropical areas, where climatic conditions are severe, are rare. They generally belong to a limited number of scorpion groups, families and genera. Species of the family Euscorpiidae, genus Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 occur up to 2000 m in the Alps [1,4], and those of the families Diplocentridae and Vaejovidae, genera Diplocentrus Peters, 1861 and Vaejovis C.L. Koch, 1836 up to 3000 m in North America [1,5,6]. In the Himalayas of India, Pakistan, Nepal and Tibet, scorpions of the families Buthidae, Chaerilidae and Scorpiopidae have been found up to 4000 to 4500 m. These contain species of the genera Hottentotta Birula, 1908, Chaerilus Simon, 1877 and Scorpiops Peters, 1861 [1,7–10]. The altitudinal record for a scorpion species goes to the South American bothriurid, Orobothriurus crassimanus Maury, 1975, collected up to 5560 m at the ‘Nevado de Huascaran’ in the Peruvian Andes [11].

According to Polis [1], high-elevation species are all small, and they feed on a diverse array of arthropods also found at these heights [10]. Their small size possibly is the consequence of the short periods during which they are able to forage. According to Crawford and Riddle [12], ‘cold hardiness’ allows at least some species to survive freezing temperatures. One spectacular mechanism is the ability to ‘supercool’, a process whereby the animal's circulatory fluid can be lowered well below the freezing point without solidification or crystallization and without any subsequent damage to the body tissue [13]. The physiological or biochemical basis for the ability of some scorpion species to ‘supercool’ is not clearly known. Increased levels of cryoprotectants such as glycerol and sorbitol in the haemolymph, known for insects living in very cold environments, were not observed for scorpions [14]. As stated by Polis [1], surprisingly, high-altitude scorpions live under rocks, in scrapes, and in relatively short burrows rather than in deep burrows with terminal chambers below the frost line [10,12]. These characteristics seem to be in accordance with that observed for the new species described at present.

2 The geographical distribution of family Liochelidae

This family is represented in all continents, except North America, mainly in tropical and parts of the subtropical zones. The family is composed of eight genera distributed as follow: Cheloctonus Pocock, 1892, southern regions of Africa. Chiromachetes Pocock, 1899, south of India. Chiromachus Pocock, 1893, Indian Ocean islands, Seychelles and Mauritius. Hadogenes Kraepelin, 1894, southern regions of Africa. Iomachus Pocock, 1893, eastern and central Africa and India. Liocheles Sundevall, 1833, Asia and Southeast Asia, Australia and Oceania islands. Opisthacanthus Peters, 1861, Africa and Madagascar, South and Central Americas, Caribbean Island of Hispaniola, Pacific Cocos Island. Palaeocheloctonus Lourenço, 1996, Madagascar.

Scorpions of the family Liochelidae are almost totally absent from mountain regions. Two exceptions concern species of the genus Opisthacanthus, O. weyrauchi Mello-Leitão, 1948 found up to 1800 m in the Peruvian ‘puna’, and O. rugulosus Pocock, 1896 found up to 2350 m in Malawi Mountains [15,16].

The finding and description of a new genus and species of liochelid scorpion from Himalayan mountain range represents two major novelties: (i) this is the first liochelid scorpion to be collected from outside the typical tropical or subtropical pattern of distribution of the family, (ii) it also represents the first liochelid species to be found in high-elevation mountain tops where climatic conditions are often severe and even extreme. The new genus and species possibly represents an isolate element of the family Liochelidae, which could have originated from a proto-element already present in the Indian plate during its migration to the Northern Hemisphere. The contact of the Indian plate with the Asian continent and the raising of the Himalayan mountain range undoubtedly isolated several groups from the Indian lowlands, including those that become adapted to high altitudes in the mountains.

Familial classification follows Prendini and Wheeler [17], who re-established the Liochelidae as a family. In our opinion this is the most justified decision, and it is adopted here.

3 Taxonomic treatment

3.1 Genus Tibetiomachus gen. n.

Diagnosis: Small scorpions measuring 26 mm in total length. Coloration reddish–yellow to reddish–brown, with some variegated zones on body and pedipalps. Pectines with 6–6 teeth. Female genital operculum large, formed by two oval to rounded-shaped plates, which are fused and with a very small incision in the base. Trichobothrial pattern of type C, minorante neobothriotaxy; chela trichobothrium dt absent. Chelicera movable finger without internal teeth. Cutting edge of pedipalp fingers with two rows of longitudinal granules, partially fused on the proximal one third; accessory granules inconspicuous. Basal region of tarsi of legs with 2/3 rows of very thin setae. Pedal spurs moderate.

4 Affinities of the new genus

The new genus Tibetiomachus has undoubtedly some affinities with the genus Iomachus Pocock, 1893, which is well represented in India. Some characters do associate these two genera such as the disposition of the granulation on the edge of the pedipalp fingers or the structure and disposition of fine setae on the basal aspect of the tarsi. For several other characters, however, the two genera diverge: (i) shape of female genital operculum, oval to rounded-shaped fused plates in Tibetiomachus gen. n.; heart-like shaped in Iomachus, (ii) trichobothrial pattern of type C, minorante neobothriotaxy, with chela trichobothrium dt absent in the new genus; orthobothriotaxy in Iomachus, (iii) chelicera movable finger without internal teeth in the new genus; movable finger with internal teeth in Iomachus. This association is only hypothetical, but it should be interesting to test phylogenetic distances between the two genera using molecular techniques, such as DNA hybridisation. Finally, the geographical distribution of the new genus is markedly different from that of Iomachus and other genera of the family Liochelidae.

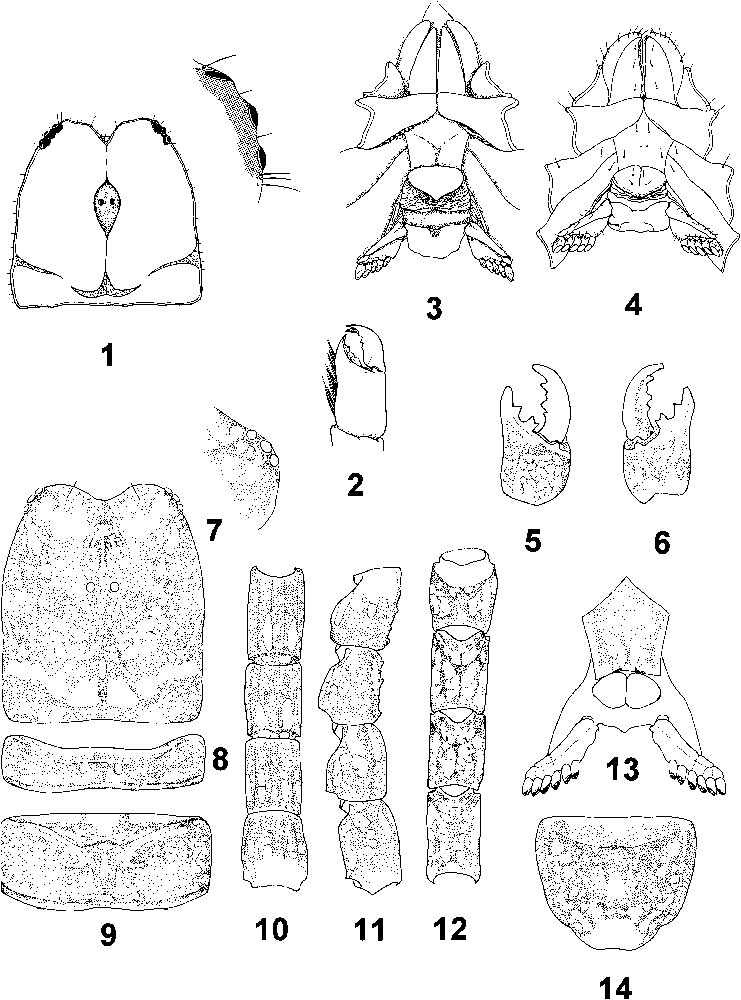

Type species of the genus:Tibetiomachus himalayensis sp. n. (Figs. 1 and 2, 5–26)

1–4. Iomachus punctulatus. 1–3. Female. 1. Carapace and detail of lateral eyes. 2. Chelicera. 3. Ventral aspect showing coxapophysis, sternum, genital operculum and pectines. 4. Idem for male. 5–14. Tibetiomachus himalayensis gen. n. sp. n. Female holotype. 5–6. Chelicera, dorsal and ventral aspects. 7. Carapace and detail of lateral eyes. 8–9. Tergites I and II. 10–12. Metasomal segments II–V, ventral, lateral and dorsal aspects. 13. Ventral aspect showing sternum, genital operculum and pectines. 14. Sternite VII.

Tibetiomachus himalayensis gen. n. sp. n. Female holotype. 15–17. Metasomal segment V and telson, ventral, dorsal and lateral aspects. 18. Cutting edge of movable finger with rows of granules. 19. Leg III, showing tarsal setae and pedal spur. 20–26. Trichobothrial pattern. 20–22. Chela dorso-external, internal and external aspects. 23–25. Patella, dorsal, external and ventral aspects. 26. Femur, dorsal aspect.

Type material: One Female holotype. China, Tibet, High Plateau, Guerla Mandhata, ∼4600 m, in soil under rocks, VII/1939 (Italian expedition leg).

Depository: Holotype in the ‘Muséum national d'histoire naturelle’, Paris.

Etymology: The specific name makes reference to the mountains where the new species was collected.

Diagnosis: as for the genus.

Description based on female holotype. Measurements after the description.

Coloration: Basically reddish–brown, with some variegated zones on the body and pedipalps. Carapace reddish–brown, with a variegated zone in the middle region; median and lateral eyes surrounded by black pigment. Tergites reddish–brown, with two longitudinal series of yellowish spots. Metasomal segments reddish–brown; segment I with the proximal half yellowish; vesicle yellowish with minute circular dark spots; aculeus slightly reddish. Chelicerae yellowish; base of fingers dark; extremity yellowish; the whole surface with a diffuse variegated fuscous colour. Pedipalps reddish–brown; femur darker than patella and chela; patella with some dark variegated spots. Venter and sternites yellowish; sternum and coxapophysis reddish; pectines and genital operculum paler than sternites; legs brownish with yellowish round spots.

Morphology. Carapace without granulations but with punctuations; furrows weakly deep. Anterior margin with a moderate concavity reaching as far as the level between the first and the second lateral eyes. Median ocular tubercle flattened and almost in the centre of the carapace; median eyes small to moderate, separated by more than one ocular diameter; three pairs of moderate lateral eyes. Sternum pentagonal, longer than wide. Genital operculum large, formed by two oval to rounded-shaped plates that are fused and with a very small incision in the base. Tergites without carinae, and with punctuations. Pectinal tooth count 6–6. Sternites smooth and shiny; VII acarinate with a few punctuations; spiracles slightly linear but inconspicuous. Metasomal segments I to V longer than wide, almost smooth and shiny, except for some sparse granulations ventrally on segment V. All carinae vestigial in segments I–IV, except for ventral carinae on I and II which present some spinoid granules; segment V rounded. All segments without any chetotaxy. Telson with pear-like shape; smooth and covered with some setae. Pedipalps: femur with dorsal internal, dorsal external and ventral internal carinae moderate; all faces smooth. Patella with all faces smooth and lustrous; dorsal internal and ventral internal carinae weak; other carinae vestigial. Chela intensely granular on dorsal and external faces; all carinae moderately to weakly marked. Chelicerae rather atypical in relation to Scorpionoidea [18]; movable finger without internal teeth. Trichobothrial pattern of type C, minorante neobothriotaxy; chela trichobothrium dt absent [19]. Legs: basal region of tarsi with 2/3 rows of very thin setae. Pedal spurs moderate to weak.

Geographic distribution: Only known from the type locality (Fig. 3).

World map showing the distribution of the family Liochelidae and, the type locality of Tibetiomachus himalayensis gen. n., sp. n. (black star).

Morphometric values (in mm) of the new species: Total length, 26.2. Carapace: length, 4.5; anterior width, 3.1; posterior width, 4.4. Metasomal segment I: length, 1.6; width, 1.2. Metasomal segment V: length, 2.1; width, 0.8; depth, 0.9. Vesicle: width, 0.9; depth, 0.9. Pedipalp: femur length, 2.9, width, 1.3; patella length, 3.4, width, 1.8; chela length, 6.9, width, 2.5, depth, 1.7; movable finger length, 2.8.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Prof. John L. Cloudsley-Thompson, London, for reviewing the manuscript.