1 Introduction

The first record of a horse chestnut leaf miner as an Asiatic species (typus generis: Lithocolletis guttifinitella) was announced by Chapman in 1902. However, already in 1985 mines dug by leaf-miner caterpillars on the white horse chestnut (Aesculus hippocastanum) leaves were found in Macedonia in the Ohrid Lake region. The second time this species was described as a species novum – Cameraria ohridella in 1986 and up-to-now it is the only representative of this genus in Europe [1,2]. Its larvae cause significant damage to the appearance of the infested tree – premature drying and leaf fall.

Since its detection in Macedonia, migration of C. ohridella to the north part of Europe via Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina has been observed. Soon, in 1989 the first observation outside the Balkan Peninsula was recorded in Linz (North Austria); then C. ohridella spread over Central Europe countries: Hungary, the Czech Republic, Poland and Germany, reaching in the year 2000 the west part of France [3,4]. In 2002, individuals of this species were unexpectedly recorded in the British Isles and since 2003 they have been reported in Spain and the Scandinavian Peninsula [4–7]. However, in Portugal the presence of C. ohridella has not been reported up-to-now [8]. The rapid territorial expansion to new areas presented above was achieved by using both active and passive means. The active way (as an aeroplankton) involves horizontal airstreams, which enable local dispersion of this species up to several dozen kilometres per year. The passive dispersion – both butterflies and pupae in fallen leaves – is possible due to car and railroad transport on distances up to 80–100 km per year [4,9].

As the C. ohridella population had already been noted since the end of 1980s, and in spite of its rapid range and size increase, the first examinations of its biology and ecology were initiated in 1994 in Austria [10]. Analyses of 12 isozymes (esterase, amylase, malate dehydrogenase, aspartate aminotranspherase, acid phosphatase, alkaline phosphatase, malate dehydrogenase, leucyl aminopeptidase, peroxidase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, alcohol dehydrogenase, octanol dehydrogenase) from six populations of C. ohridella collected at different sites in Central Europe (Austria) revealed that European population of the horse chestnut leaf miner is genetically homogenous. Moreover, RAPD-PCR analyses and mDNA sequencing indicate that European populations have a common ancestor [11].

In relation to its biology, C. ohridella females lay eggs (0.2–0.4 mm) individually on the upper side of a leaf along the longitudinal leaf vein and up to 100 eggs can be found on one leaf of the horse chestnut [9,12]. Embryos develop 2–3 weeks with 30% mortality and this process is weather-dependent [10,13]. The larval development of the 1st spring generation lasts 3–6 weeks, and the last, in the Central Europe, usually 3rd generation, 5 weeks [10]. The larvae of the 1st stage start to feed at the site of eclosion. The larva punctures the upper layer of epidermal cells and drills a 1–2 mm long corridor. The corridor is gnawed out along side veins resulting in brown, circle mine [12]. The 1st (L1) instar caterpillars feed on liquid food only – the sap feeding phase – and reach 0.4–0.5 mm length [14]. The L2 and L3 instars (respectively, 1.2 and 2.1 mm long) feed on solid parts of leaf tissue – tissue-feeding phase – what causes 5–8 mm light green paths of mines [15]. The last feeding stage, larvae of L4, makes irregular 3–4 cm long mines (of area 4–8 cm2) [12].

There is by no means agreement as to how many larval stages characterize C. ohridella – some authors mention five stages, others four larval and two pre-pupae stages. The pre-pupae stages spin cocoons where pupation occurs. A part of pre-pupae (L5 stage) turns into non over-wintering pupae (development time about 14 days) and creates the next generation at the same season. The other part of L5 turn into L6 pre pupae stage, produces winter pupa's cocoons and develops into wintering pupae (6–9 months) which creates the first generation during the following spring [10,12,16].

C. ohridella is a polyvoltine species which produces a few (2–5) overlapping generations per year. The number of generations depends on food sources and weather conditions [10,17]. The Balkans and Central European populations generally produce three generations during one season [18]. In the climate conditions of Central Europe imagoes of the first generation appear in May, the second in June, and the third in September [10]. Imagoes of the first generation fly about one month and this activity is synchronized with the white horse chestnut flowering [18].

As the insects’ larvae development depends on food quantity and quality, especially on the protein/carbohydrates ratio, herbivorous insects actively search the optimal food [19]. Leaf miner larvae are not able to change a particular host plant, so they are subjected to every change in food quality, this concerns especially allelocompounds synthesis during a season [20]. Main allelocompounds of Aesculus hippocastanum leaves and seeds are saponins and glycosides [21] and differences in this composition among horse chestnut species are measurable [22].

Synthesis of a set of specific enzymes ensures proper quality and quantity of nutritional compounds that are necessary to the reproductive success of specialized herbivores [23,24].

Hitherto studies on Lepidoptera digestion have focused mainly on enzyme activities in pest species important from an economical point of view, because effective biological methods of pest control appear to be leading issues in insect molecular physiology. So far, digestive enzymes of leaf miners have never been extensively investigated. Their small size, hidden larval stage, and the considerable effort required to collect a sufficient amount of biological material are the reasons that this investigation of insects is difficult for researchers. Until now there are only a few records about leaf-miner digestive enzymes. One of them concerns the coffee leaf-miner, Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). Moreover, the present means of its control are troublesome, so a possible point of attack to that pest is using inhibitors of enzymes taking part in the primary digestion, like trypsin inhibitor from castor bean leaf extracts [25]. Genetic modification of allelocompounds synthesis (e.g. proteases or amylase inhibitors) in A. hippocastanum seems to be one of the ways of control of C. ohridella. Both fast territorial expansion and abundance of C. ohridella give a chance to improve our knowledge about this group of Lepidoptera and its digestion processes. As leaf-miners mostly utilize various carbohydrate components present in leaf tissues, emphasis in this article is placed on the carbohydrate digestion.

2 Material and methods

The caterpillars of C. ohridella were collected from white horse chestnut leaves from an experimental plot in the biggest rest area of Upper Silesia – the Voivodship Park of Culture and Recreation in Chorzów (Southern Poland). Randomly chosen leaves with mines characteristic of the L4 caterpillar stage were collected three times during one vegetation season (from June until September) from chemically unprotected white horse chestnut trees. Collecting was synchronized with the development of three generations of C. ohridella.

Only larvae of the L4 instar (a hyperphagic tissue-feeding phase) were selected for biochemical examination. Dissected larvae's digestive tracts were rinsed in 1.15% KCl solution at 4 °C. Washed midguts collected from 20 specimens (this constituted one sample) were homogenised in 1 ml of the same solution and then centrifuged for 10 min (3000 × g) at 4 °C. Supernatant (divided into a few sub-samples) was kept frozen at −70 °C until the analysis of enzyme activities. Enzymatic activities were assayed spectrophotometrically in six independent samples, the measurements of each hydrolytic activity were duplicated, and the mean from both results were calculated for a particular sample. In accordance with the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology all measurements of enzymatic activity were conducted at 30 °C, but the activity of examined enzymes was previously checked also at other temperatures, in a range of 15–50 °C, every five degrees, to avoid a hypothetical case that this activity would be minimal at 30 °C – the data are not presented.

Protein concentration was determined according to Bradford [26].

For the detection of initial and rapid qualitative enzyme activity in samples from the whole midgut homogenate, the commercially available Api®ZYM test (bioMérieux Inc.) was used. Measurements according to the producer's instructions were performed in samples (65 μl) containing about 200 μg of protein per millilitre of homogenate. After 4 h of incubation the test strip was read by comparing the developed colour in each test cupule with a standard colour chart supplied by the producer, expressed in the scale from 0 (no enzyme reaction) to +5 (very high enzyme activity). This test was used as a screening tool only for identification and selection of the main hydrolytic enzymes of C. ohridella midgut for further spectrophotometric analyses. The procedures of enzymatic assays, as well as substrates used for spectrophotometric analyses, are shown in Table 1. To obtain the most appropriate procedure for the main analysis for major glycosidases and proteases, the optimal pH, as well as the enzymatic reaction slope in relation to incubation time, were estimated. Ionic strength of the buffers was applied according to the methods described for other Lepidoptera species.

Assay conditions and methods used in the determination of glycosidases and proteases.

| Enzyme | Substrate | Buffer for substrate | Homogenate volume [μl] | Incubation [min] | Termination | Further procedures | Final vol. [ml] | Final product | λ [nm] | Comments | References |

| α-amylase | 100 μl 0.5% water-soluble starch | Tris-HCl 0.05 M; pH 8.8; 20 mM NaCl, 0.01 mM CaCl2 | 20 | 120 | 200 μl of 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid reagent | 10 min in water bath (100 °C) + 300 μl H2O | 0.62 | Maltose | 540 | Measurement after 10 min (until 1 h) | [27] |

| Maltase | 10 μl 0.056 M maltose | Citrate-phosphate 0.05 M, pH 6.2 | 10 | 60 | 200 μl 5% TCA | 50 μl (of 210 μl mixture) + 750 μl working reagent from diagnostic kit, incubation: 15 min at 37 °C | 0.8 | Glucose | 500 | Working reagent (pH 7.0): GOD, POD, 4-amino-antypirine, (POCh SA)measurement until 30 min | [28] (modified) |

| Cellobiase | 10 μl 0.056 M cellobiose | ||||||||||

| Lactase | 10 μl 0.056 M lactose | ||||||||||

| Saccharase | 10 μl 0.056 M sucrose | ||||||||||

| Trehalase | 10 μl 0.056 M trehalose | 240 | |||||||||

| α-glucosidase | 45 μl 20 mM NP-α-Glu | 45 | 15 | 450 μl 1% SDS in 0.1 M bicarbonate buffer pH 10.4 | – | 0.6 | p-nitro-phenol | 420 | measurement until 120 min | [29] (modified) | |

| β-glucosidase | 45 μl 20 mM NP-β-Glu | ||||||||||

| α–galactosidase | 45 μl 8 mM NP-α-Gal | ||||||||||

| β-galactosidase | 45 μl 20 mM NP-β-Gal | ||||||||||

| Total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity | 350 μl 1% azocasein | Tris-HCl 0.05 M, pH 8.0 | 50 | 240 | 300 μl 10% TCA (15 min of precipitation of azocasein fragments) | Centrifugation at 10000 × g, 10 min | 0.5 super-natant + 0.333 1 N NaOH | Azo-peptides | 366 | Measurement until 10 min | [30] |

| Carboxy-peptidase | 10 μl 1 mM | 90 μl Tris-maleic, 0.05 M; pH 7.0 with 0.1 M NaCl | 10 | 180 | 300 μl acetate buffer: 0.4 M, pH 5.0 | 400 μl 4% ninhydrin; 30 min: 100 °C, | 2.0 | Leucine | 570 | Measurement after 30 min | [31] |

| N-CBZ-V-L | chilling + 1.2 ml 50% ethanol | ||||||||||

| Aminope-ptidase | 600 μl 1 mM L-pNA in 10% DMF | Tris-HCl, pH 7.8; 5 mM MgCl2 × 6 H2O | 30 | 120 μl 20% acetic acid | – | 0.73 | Nitro-aniline | 410 | Measurement after 30 min; ɛ410 = 8800 | [32] | |

| Trypsin | 90 μl 1 mM B-R-pNA in 15% DMF | 510 μl Tris-HCl 0.05 M, pH 9.0 20 mM CaCl2 | |||||||||

| Chymotrypsin | 90 μl 1 mM G-F-pNA in 10% DMF; | 510 μl glicyne -NaOH 0.05 M, pH 9.8; 20 mM CaCl2 | 120 | [31,32] | |||||||

| 90 μl 1 mM Suc-AAPF-pNA in 15% DMF |

One-way ANOVA statistics were applied to perform analysis of the results. To estimate the significant differences between the subsequent generations post hoc analysis of variance was done using Tukey's HSD test (p < 0.05). Pearson's linear correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) was calculated between enzymes activities.

3 Results

The preliminary results obtained using Api®ZYM test indicated the highest proteolytic activity for leucine and cysteine arylamidase as well as glycolytic activity for α-glucosidase and n-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase. This test also displayed high activities of alkaline and acid phosphatases (Table 2).

Api®ZYM enzyme assay results from whole midgut homogenates of Cameraria ohridella (relative strength of reaction according to producer chart scale, from 0 (no enzyme reaction) to +5 (very high enzyme activity).

| Enzyme | Reaction strength |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 5 |

| Esterase | 1 |

| Esterase lipase | 2 |

| Lipase | 1 |

| Leucine arylamidase | 5 |

| Cysteine arylamidase | 5 |

| Valine arylamidase | 2 |

| Trypsin | 1 |

| α-Chymotrypsin | 1 |

| Acid phosphatase | 4 |

| Phosphoamidase | 2 |

| α-Galactosidase | 1 |

| β-Galactosidase | 2 |

| β-Glucoronidase | 0 |

| α-Glucosidase | 5 |

| β-Glucosidase | 2 |

| n-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase | 5 |

| α-Mannosidase | 0 |

| α-Fucosidase | 1 |

3.1 Optimal pH for enzymes activity

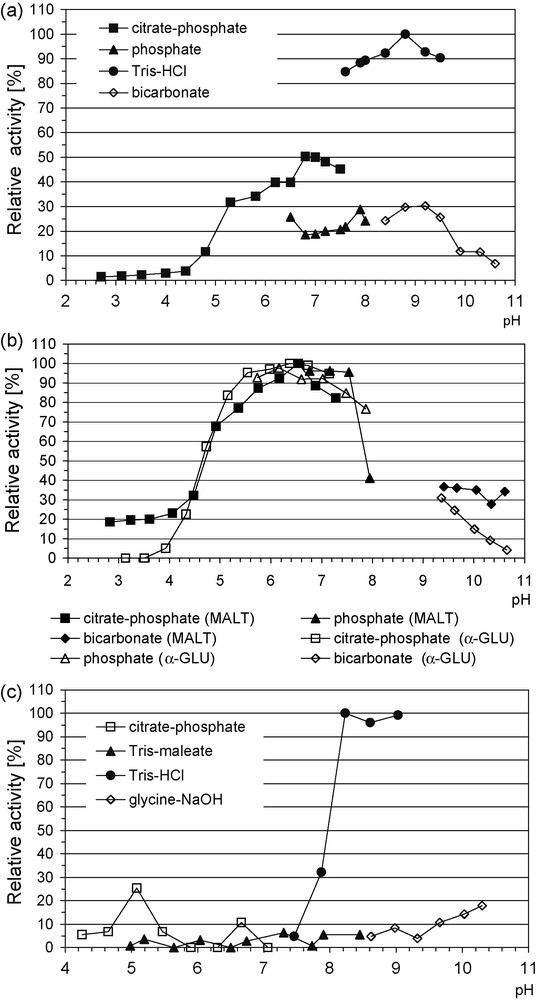

The optimal pH for α-amylase activity was 8.8. Over and below this value the hydrolytic activity was low, and at the pH of 5.0 did not take place at a perceptible rate (Fig. 1a). For maltase the optimal pH was 6.2, and for α-glucosidase activity the optimal pH was in the wide range (5.5–6.6), rapidly decreasing at pH less than 4.9 and above 8.0 (Fig. 1b).

The activity of midgut digestive enzymes in Cameraria ohridella larvae in relation to buffers pH: a: α–amylase; b: maltase and α–glucosidase; c: total proteolytic (caseinolytic) activity.

For proteolytic activity (caseinolytic) the optimal pH range was 8.0–9.2, when using Tris-HCl buffer. Using other buffers resulted in generally very low proteolytic activity, independently of the pH range (Fig. 1c).

3.2 Saccharolytic activity

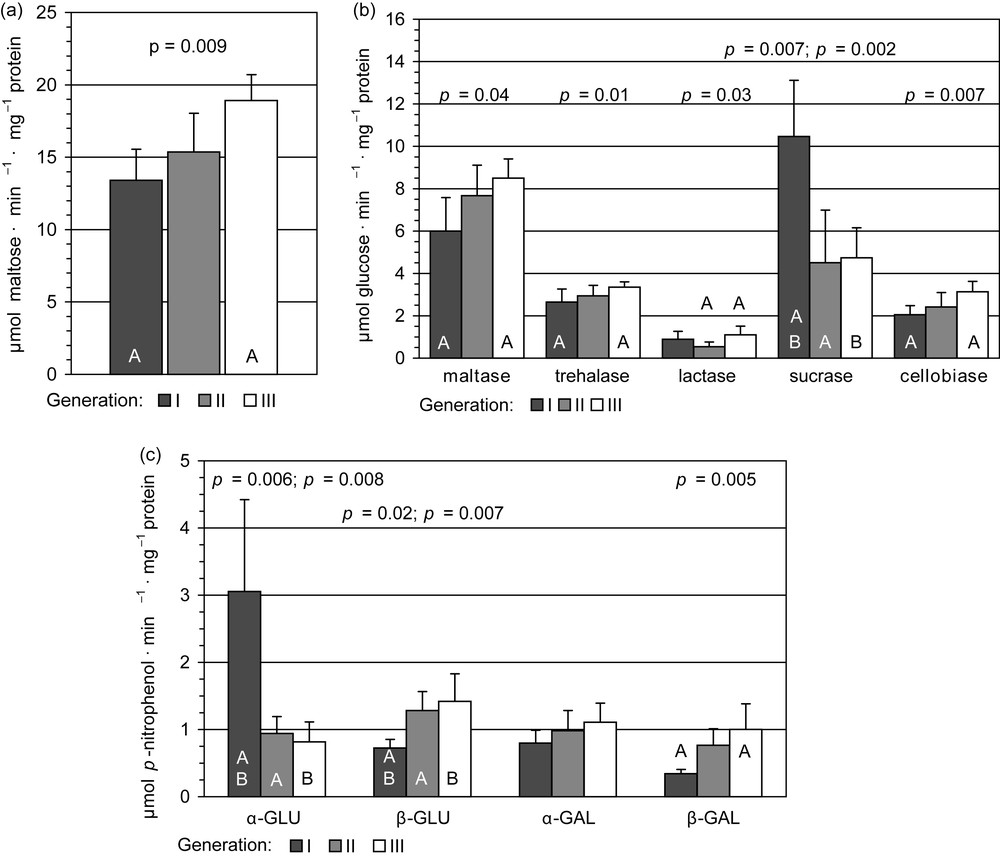

Activity of α-amylase (an enzyme responsible for digestion of starch present in the leaves of horse chestnut) in homogenates obtained from the whole midguts of individuals of each generation increased successively in subsequent generations, reaching 140% value in the third compared with first generation individuals (Fig. 2a). This activity increase is significantly higher. Similarly, the highest activity in homogenates from third generation individuals was recorded also in the case of disaccharidases: maltase (142%), which reflected α-amylase activity, but also celobiase (168%), trehalase (137%) (Fig. 2b), and some of glycosidases: activities of β-glucosidase (199%) and β-galactosidase (314%), compared with values detected in homogenates from larvae of the first generation. The same trend was observed for α-galactosidase activity, but the differences among the means were not statistically significant (Fig. 2c).

Specific glycosidases activities in midgut tissue samples in I, II, III generation of Cameraria ohridella larvae: means ± S.D., n = 6. The same letter indicates the significant differences in the enzyme activity between generations by T Tukey's test for unequal sample size. Activities: a: α-amylase; b: specific disaccharidases; c: specific glycosidases. α-GLU: α-glucosidase; β-GLU: β-glucosidase; α-GAL: α-galactosidase; β-GAL: β-galactosidase.

Unexpectedly, the opposite effect occurred in the case of α-glucosidase (a decrease of 66% for α-glucosidase) in the third generation; also sucrase activity was lower in homogenates from the third generation individuals compared with the first generation (about 48%) (Fig. 2b and c).

A completely different pattern of enzyme activity was found for lactase: in the second generation it diminished (61% of the value obtained for the first generation), in the third generation it rapidly increased, reaching 132% values of the first generation, but the significant differences were observed, when only comparing values obtained for the second and third generations (Fig. 2b).

3.3 Proteolytic activity

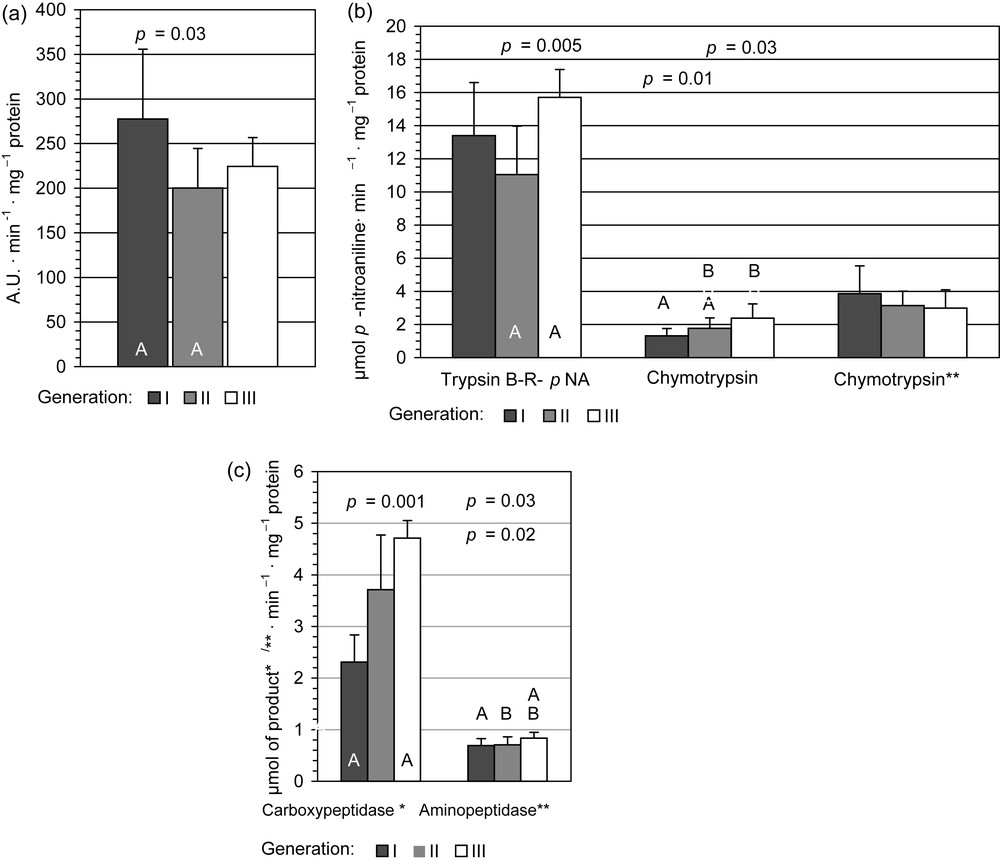

Patterns of peptidases activity were generally similar to those observed in carbohydratase activity. The highest enzyme activity in the homogenates from midguts of the third generation individuals was observed in the case of chymotrypsin for G-F-pNA substrate (195%) (Fig. 3b), aminopeptidase (129%) and carboxypeptidase (202%) (Fig. 3c) compared with values obtained for the first generation.

The proteolytic activities in midgut tissue samples in I, II, III generation of Cameraria ohridella larvae: means ± S.D., n = 6. The same letter indicates the significant differences in the enzyme activity between the generations by T Tukey's test for unequal sample size. Activities: a: Total proteolytic activity. A.U.: Activity Unit; b: endoproteolytic activities: * Chymotrypsin assayed with G-F-pNA (N-glutaryl-L-phenylalanine p-nirtoanilide); ** Chymotrypsin assayed with Suc-AAPF-pNA (N-succinyl-alanine-alanine-proline-phenylalanine p-nitroanilide); c: exoproteolytic activities: product of reaction: * μmol of leucine min−1 mg protein−1; ** μmol of nitroaniline min−1 mg protein−1.

The opposite effect occurred in the case of general proteolytic activity but the significant differences were observed only when compare values obtained for the first generation with the second generation ones (Fig. 3a).

The activity of trypsin reflected total proteolytic activity patterns – in the second generation this was diminished (77% value of the first generation), while in the third generation rapidly increased, reaching 121%, but the significant differences were observed only when compare values obtained for the third generation with the second generation ones (Fig. 3b).

3.4 Correlation between enzyme activities

Although the examined enzymes are products of independent translation processes, running parallel to each other, they act together, and regulatory factors coordinate their activity, so some correlations between examined enzyme activities were found and are presented in Table 3. The determination of enzyme activities was made in the same samples; therefore correlations reflect relationship between different enzyme activity.

The significant correlations between the activities of assayed glycolytic and proteolytic enzymes in the midgut tissues of Cameraria ohridella consecutive larvae generation I, II, III.

| Generation | n | Regression equation | r | p | t |

| I | 6 | yCASE = 169.765xCHYM(G-F-pNA) + 53.694 | 0.952 | 0.001 | 6.978 |

| I | 6 | yα-GAL = 0.018xAMINO – 0.3754 | 0.913 | 0.011 | 4.467 |

| I | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.041xSUCR + 0.3012 | 0.856 | 0.029 | 3.320 |

| I | 6 | yCASE = 20.738xTRYP – 0.322 | 0.848 | 0.016 | 3.592 |

| I | 6 | yα-GAL = 0.060xSUCR + 0.168 | 0.844 | 0.034 | 3.151 |

| I | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.544xα-GAL + 0.292 | 0.818 | 0.046 | 2.852 |

| I | 7 | yTRYP = 0.110xCHYM(G-F-pNA) − 0.154 | 0.802 | 0.029 | 3.006 |

| I | 6 | yβ-GAL = −0.101xCARB + 0.573 | −0.891 | 0.016 | −3.942 |

| I | 6 | yCELO = −0.119xTRYP + 3.579 | −0.845 | 0.034 | −3.160 |

| II | 6 | yα-GLU = 0.372xCHYM_G-F-pNA + 0.302 | 0.973 | 0.001 | 8.555 |

| II | 6 | yTRYP = 0.179xAMINO – 1.620 | 0.957 | 0.001 | 7.437 |

| II | 6 | ySUCR = 4.752xTREH − 9.452 | 0.951 | 0.003 | 6.156 |

| II | 6 | yα-GLU = 0.797xα-GAL + 0.158 | 0.947 | 0.003 | 5.956 |

| II | 6 | yMALT = 2.193xCHYM(Suc-AAPF-pNA) + 1.329 | 0.934 | 0.006 | 5.235 |

| II | 6 | yα-GLU = 8.986xSUCR − 3.939 | 0.918 | 0.009 | 4.644 |

| II | 6 | ySUCR = 3.329xCHYM(G-F-pNA) − 1.192 | 0.890 | 0.017 | 3.915 |

| II | 6 | ySUCR = 8.660xLACT − 0.812 | 0.884 | 0.046 | 3.279 |

| II | 6 | yTREH = 0.657xCHYM(G-F-pNA) + 1.811 | 0.879 | 0.020 | 3.692 |

| II | 6 | yα-GAL = 0.398xCHYM(G-F-pNA) + 0.300 | 0.875 | 0.022 | 3.629 |

| II | 6 | yα-GLU = 0.446xTREH − 0.372 | 0.874 | 0.022 | 3.613 |

| II | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.486xTREH − 0.087 | 0.863 | 0.026 | 3.424 |

| II | 6 | yβ-GAL = 2.396xCELO + 0.578 | 0.859 | 0.028 | 3.368 |

| II | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.783xα-GAL + 0.572 | 0.844 | 0.034 | 3.157 |

| II | 6 | ySUCR = 1.444xMALT − 6.571 | 0.836 | 0.037 | 3.053 |

| II | 6 | yTREH = 0.373xCARB + 1.601 | 0.825 | 0.043 | 2.924 |

| II | 6 | yCASE = 42.029xCHYM(Suc-AAPF-pNA) + 68.150 | 0.821 | 0.023 | 3.224 |

| III | 6 | yβ-GLU = 1.437xα-GAL − 0.237 | 0.985 | 8.4·10 −5 | 16.229 |

| III | 6 | yCELO = 0.487xMALT − 0.899 | 0.967 | 0.006 | 6.667 |

| III | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.8673xβ-GAL – 0.172 | 0.938 | 0.005 | 5.422 |

| III | 6 | ySUCR = − 1.544xMALT − 8.219 | 0.924 | 0.024 | 4.210 |

| III | 6 | yα-GLU = 0.904xTREH − 2.085 | 0.919 | 0.026 | 4.062 |

| III | 6 | yα-GAL = 0.679xβ-GAL + 0.426 | 0.909 | 0.011 | 4.381 |

| III | 6 | yLACT = 0.846xβ-GAL + 0.071 | 0.906 | 0.012 | 4.301 |

| III | 6 | yMALT = 0.523xTRYP + 0.151 | 0.898 | 0.038 | 3.537 |

| III | 6 | yβ-GLU = 0.890xLACT + 0.376 | 0.881 | 0.020 | 3.724 |

| III | 6 | yCELO = 0.035xAMINO + 0.266 | 0.869 | 0.024 | 3.521 |

| III | 6 | yα-GAL = 1.204xLACT – 0.234 | 0.839 | 0.036 | 3.095 |

| III | 6 | ySUCR = 2.431xCELO − 2.880 | 0.839 | 0.036 | 3.092 |

The particular correlations differed in subsequent larvae generations, but some general patterns could be observed. Discarding the obvious correlations inside the main groups (disaccharidases, glycosidases and proteolytic enzymes) we found correlation between saccharolytic and proteolytic activity manifested in the first larvae generation in the following cases: α-galactosidase–aminopeptidase, celobiase–trypsin, and β-galactosidase–carboxypeptidase. The last two indicate very strong negative correlation, lower than r = −0.8. Further correlations between carbohydratase and peptidase activity were observed in the second larvae generation. Instead of positive and negative correlations described above, we noted some new ones: maltase–chymotrypsin, trehalase–carboxypeptidase, trehalase–chymotrypsin, sacharase–chymotrypsin, α-glucosidase–chymotrypsin and α-galactosidase–chymotrypsin activities. Only a few correlations were found between carbohydratase and peptidase activities in larvae of the third generation. We noted this relation only in two cases: maltase–trypsin and celobiase–aminopeptidase activity.

Paradoxically, there were no correlations between amylase activity and subsequent disaccharidases – probably amylase acted in excess and starch was not a limiting factor. Only one positive correlation (statistically significant) – α-glucosidase–α-galactosidase – was manifested in all three generations. Activities of sucrase and maltase were also very strongly correlated in insects from the second and third generation.

4 Discussion

The optimal pH for the assayed enzymes in C. ohridella larvae were generally similar to those described previously for other lepidopterans. For the majority of examined digestive enzymes in caterpillars’ midgut, an alkaline pH is required to obtain maximal efficiency [33,34,35]. The exceptions, like maltase, α-glucosidase and carboxypeptidase activity were also reported previously for other species and particular enzymes, because many enzymes act in a broad pH range, e.g. the optimal pH for starch hydrolysis in Earias vitella (Noctuidae) is placed between 5.5 and 9.0 [36]. Comparing the above-cited data with our results obtained for leaf-mining caterpillars, we can state that for the pest C. ohridella the optimal pH pattern for digestive enzymes activity is similar to that in other, non-leaf-mining lepidopterans. The pH gradient in Cameraria midgut compartments was not measured, so it is also possible that in the real, intact conditions, the above mentioned enzymes act in less alkaline milieu. The pH of digested content in caterpillar midgut also is different in its anterior and posterior part. Usually, the posterior part is less alkaline, as well as the ectoperitrophic space in comparison to the endoperitrophic space [37]. The profile of C. ohridella digestive enzymes did not significantly vary among the following generations, feeding on aging leaves, in fact still on the same leaf or in the close neighbourhood. Probably glycosides and escins [21] as well as some volatile oils [22] present in leaf tissues are protective allelocompounds used by this tree against insect herbivores, but insufficient in the case of Cameraria. Every next generation of the pest is more numerous, with reference to both infected trees and leaves. A general principle is that, during evolution, plants can weaken the destructive effects of insect hydrolases at the expense of inhibitors in various ways, including increasing the inhibitor activity and heterogeneity, increasing the complexity of an inhibitor set and producing highly specific insect enzyme inhibitors and bifunctional amylase/proteinase inhibitors expressed by Konarev [38] is not fully consistent with our results. In the present study examined digestive enzymes were not selectively inhibited in the following generations (except for α-glucosidase and sucrase activity) showing that the thesis about strong chemical defence of infected trees is not true in relation to a relatively new pest, in a particular region of Europe, C. ohridella. Rather small numbers of serious natural herbivores on A. hippocastanum during the hundreds years of its plantation, or limited natural dispersions in Europe, could decrease synthesis of protective allochemicals, which is always expensive for energy allocation in a tree. The opposite hypothesis – that horse-chestnut tree was strongly protected by allochemicals and that is why it was not seriously invaded by local pests – is now doubtful to maintain, because in this tree any particular strong antifeeding allelocompound was not yet described. Our results also did not indicate any special digestive activity in C. ohridella, which should be responsible for breaking the horse chestnut's chemical defence. However, we should express that our measurements did not detect any specific inhibition of digestive enzymes due to lack of measured enzyme activity with enzymes inhibitors. We also should consider the level of detoxifying enzymes or molecular interactions, e.g. at the level of gene expression, both hydrolytic and detoxifying enzymes.

The amylase activity was similar to values previously reported by Santos and Terra [34] and typical of other lepidopterans, with reference to the available data collected by Terra and Ferreira [29]. We do not know if the mechanisms of amylase production, storage and secretion by intestinal epithelium cells in C. ohridella are similar to that stated in larvae of Erinnyis ello (Sphingidae) [34] and Spodoptera frugiperda (Noctuidae) [28], but the final enzyme activity is close to that in the above mentioned non leaf-mining species.

Disaccharidases activities varied from two to 10 units (μmol substrate per minute), except for lactase, whose activity was lower. These enzyme activity values were placed in the wide range reported by other authors [44]. Maltase and sucrase activities were higher than the activities of other disaccharidases, which indicates that maltose as a product of amylase activity and leaves’ sucrose are the main disaccharides digested. The obtained disaccharidase activity values were about 10 times higher than those in Parnassius apollo (Papilionidae) [35], which probably reflects the availability of disaccharides – greater in chestnut leaves devoured from the inside, than in the case of bitten big particles Sedum telephium – a host plant for the Apollo butterfly. Feeding pattern of leaf-miner caterpillars allows them to utilize more efficiently the content of leaves’ parenchyma tissue cells, rich in low molecular disaccharides. Significantly higher activity of sucrase in the first generation of larvae may probably reflect the higher content of disaccharides in young, growing leaves in the spring.

Trehalase activity was similar to that described in other Lepidopterans: Orthaga exvinacea and Lymantria dispar [27,32] and significantly higher than in the above mentioned Apollo butterfly [35]. Trehalose is not only an endogenous energy source buffering the actual saccharide availability [23], but is also a regulatory factor in intestinal absorption and osmotic homeostasis [32], so the adequate trehalase activity is significant for the insect. In our case the level of this activity – treated as a biomarker – allows us to state that trehalose/trehalase-dependent processes were intact in Cameraria and it was an additional benefit enhancing the effectiveness of this pest. It seems notable that data obtained by us show that trehalase activity, as well as trehalose metabolism, plays an important role for leaf-mining caterpillar feeding.

Activity of glycosidases in C. ohridella is strictly dependent on a type of glycoside bonds: activity enzymes oriented towards β-bond oscillated about one unit, while this one oriented towards α-glycoside bond was high because of high level of disaccharides in young, growing leaves. This suggests that neither cellulose nor glycosides are important in the C. ohridella diet. However, we can state that glycosidic activity, related with polysaccharides digestion (mainly amylase and maltase involved in starch digestion) statistically increased in 3rd generation in comparison with 1st. This phenomenon can be explained by changes in leaves’ saccharide composition during their aging – larvae of 3rd generation from the last summer feed on mature leaves. The higher glycosidic activity (especially β-glucosidase, and except for α-glucosidase), in the third generation may also suggest that these enzymes are involved in detoxifying processes in C. ohridella feeding on aging leaves, as in the majority of insects [39,40] where toxic β-glucosides and their aglycones can appear in higher concentration. However, we can suppose that glycosides produced by the white horse chestnut (or their relatively low concentration) are not seriously dangerous to C. ohridella, while the other chestnut species, e.g. red horse chestnut, developed more efficient glycoside weapons [41].

Proteolytic activity was similar to that in other herbivorous insects [29] and reflected the fact, that leaves are generally a poor source of proteins. Bearing in mind the particular properties of insect proteases [24,42] to determine proteolytic activity, we used substrates previously tested in other insect species [43].

The optimal pH conditions for assayed proteolytic activity in total midgut samples of C. ohridella using azocasein as a substrate were similar to those found in other lepidopteran species and its pH range is from 8.0 to 9.5 [24,44,45]. Despite the fact that C. ohridella is a strict monophagous species, preferring feeding even on particular horse chestnut forms, e.g. white flowering trees, its casenolityc activity is 3–4 times lower than in other monophagous caterpillars like the Apollo butterfly [43]. These data confirm the general rule that the proteolytic activity of monophagous species, including leaf-miners, is a few times lower than in polyphagous species [24,45]. In leaf-mining insects this fact is even more strongly expressed. The obtained data point out that the total proteolytic activity in C. ohridella is dominated by one main proteinase – belonging to endopeptidases – trypsin what is important for all C. ohridella generations. The optimal pH for trypsin activity in C. ohridella was stated below 10.0. This means that trypsin can be classified as a low-alkaline trypsin type, according to Houseman et al. [44]. The activity of trypsin was about five times higher than that of chymotrypsin. Similar results were obtained for some other insects’ species, like Ostrinia nublilis and Pyralis interpunctuella (Pyralidae), Heliotis zea (Noctuidae) and Parnassius apollo (Papilionidae) [43–46]. Otherwise, in Pieris rapae (Pieridae) or Helicoverpa armigera (Noctuidae) activity of both enzymes were at a comparable level [24,47]. The strong positive correlation between casenolityc and trypsin activity, particularly for the first generation of insects, was also stated. Measurement of chymotrypsin activity may arise a problem; in the past 10 years the majority of authors suggested using sufficiently long compound as a substrate (at least five aminoacids), e.g. Suc–AAPF–p NA, to avoid inadequate binding by this enzyme [42]. Taking into consideration this restriction we used two substrates: recommended Suc-AAPF-p NA and frequently used G-F-p NA. Surprisingly, in C. ohridella both substrates gave similar results. This may suggest that the active centre of chymotrypsin is more “universal” and does not prefer particular aminoacid sequences. The data for proteolytic activity again may confirm our previous statement that the nutritional composition of young, spring leaves of horse-chestnuts demands a specific isoenzymes profile. However, this hypothesis requires further investigation, especially at isoenzymatic level, for its confirmation.

Relatively low activities of endoproteases in the midgut of C. ohridella suggest that leaf proteins are not efficiently utilized – it is possible that the level of free aminoacids and soluble low molecular weight proteins in leaves is sufficient for the development at the two early stages of larvae. We have to take into consideration shifting from the “sap-feeding phase” into “tissue-feeding phase” of 3rd stage of larvae [14,15]. It confirms the hypothesis that enzymatic (isoenzymatic) profile of digestive proteases can be changed during the larval development. Further investigations of digestion process in 1st or 2nd stages of larvae should solve unambiguously these problems. Limited availability of leaf proteins points out that leaf-mining larvae of older stages (“tissue-feeding phase”) have to obtain exogenous aminoacids also from soluble oligopeptides or from protoplasts proteins. However, it was observed that the anterior part of midgut, in opposite to a posterior part, of the dissected larvae of the 4th stage contained a lot of chlorophylls from devoured tissue, what could be related to simultaneous digestion of chloroplast proteins. Obtained oligopeptides are able to easily pass through the perithrophic membrane into the exoperitrophic space, where exopeptidases continue protein digestion. Both, carboxy- and aminopeptidase activity were easily measured in the whole midgut samples from Cameraria. Aminopeptidase activity level in C. ohridella is comparable with results obtained for Lymantria dispar and Heliotis zea [32,46]. This confirmed observations that activity of these enzymes in leaf-eaters is much higher than in other herbivorous species especially with reference to carboxypeptidase activity [45], which in C. ochridella midgut was higher than activity of aminopetidase. The high positive correlation between trypsin and aminopeptidase activity (r = 0.957), especially in the second generation, may confirm the main role of these enzymes in protein digestion.

Activity of the majority of examined enzymes increased in following successive larvae generations. It seems to be correlated rather with the food quality – older leaves are more difficult to digest – and the assimilation/consumption rate should be compensated by enhanced enzymatic activity [48]. The only exception of the rule concerns activity of α-glucosidase and sucrase – in this case the highest activity was noted in the larvae of the first generation. This may be related to higher content of disaccharides in young, developing leaves.

Activity of glucosidases, as potential detoxifying enzymes in our study varied and a common pattern was not observed, while in insects seriously intoxicated, e.g. by cyanides in the case of aphids, activity of detoxifying enzymes was correlated with a particular generation, and one metabolic path was replaced by another, more effective in a particular case [49]. It is possible that the general tendency observed by us in hydrolases activity is a nonspecific, efficient mechanism at this stage of co-evolution of horse chestnut and C. ohridella, because, according to Konarev [38] insects in turn, can decrease the influence of inhibitors by increasing digestive enzyme activities, or by modifying a set of related activities of various digestive hydrolases, or by decreasing enzyme sensitivity to inhibitors and finally by destroying inhibitors in guts by proteinases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Polish State Committee for Scientific Research, Project No. 2 P04F 033 30 realized at University of Silesia in Katowice. Dr Stanislawa Dolezych is acknowledged for many valuable comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Special thanks to Prof. Jacques Lehouelleur for reviewing the language of an abstract.