1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, the virus causing Covid-19, was first detected in Wuhan in China, in late December 2019 (ProMED, 2019; N. Zhu et al., 2020; D. L. Yang, 2024). The new disease was identified via clusters of patients seeking treatment in various hospitals in Wuhan (Worobey, 2021), many of which were vendors from the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market (hereafter “Huanan market”). The market was known to sell live animals (Tan et al., 2020); wildlife trade was therefore considered as a likely source of the outbreak (G. Wu, 2020). In an effort to control the outbreak, the market was closed in the early hours of January 1st, 2020 (D. L. Yang, 2024). However, SARS-CoV-2 was already spreading from human to human outside of the market by the time the market was closed (C. Huang et al., 2020; Q. Li et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2021). Whether it was the only source of the outbreak or not, closing the market on January 1st, 2020, was therefore insufficient to control the outbreak, which grew out of control, spread across the world, and caused a pandemic.

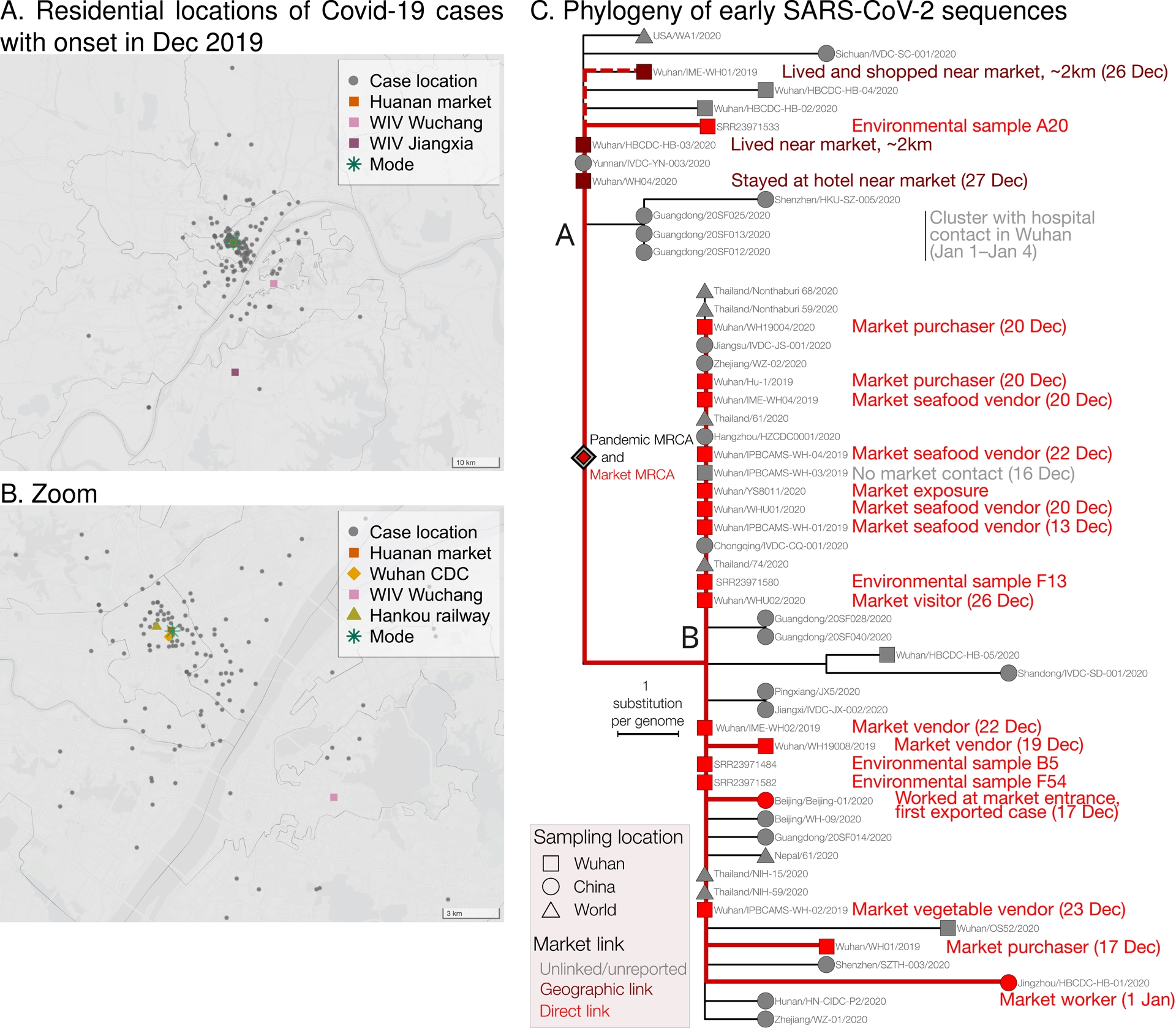

The Covid-19 pandemic was a major event in the history of the 21st century, and it is therefore important to understand what originally caused it. Available data, to date, point to a zoonotic origin linked to the wildlife trade at the Huanan market (Crits-Christoph, Levy, et al., 2024; Holmes, 2024), a conclusion supported by multiple lines of evidence. SARS-CoV-2 is a generalist virus, readily able to infect various mammal species (Nerpel et al., 2022; EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW) et al., 2023), and even to be transmitted among several of them, including raccoon dogs (Freuling et al., 2020, shown experimentally). Early human cases, with disease onset in December 2019, were retrospectively identified, and the locations of their residences mapped (World Health Organization, 2021). This revealed a striking pattern: the cases were centered around the Huanan market, whether they were epidemiologically linked to it (e.g., vendors or buyers), or not (Worobey et al., 2022; Débarre and Worobey, 2024a; Débarre and Worobey, 2024b) (see Figure 1A–B). The early lineages of SARS-CoV-2 (lineage B and lineage A (W. Liu et al., 2022)) were both present in the Huanan market, suggesting that they emerged, or at least evolved, there (see Figure 1C). Finally, live animals were sold in the Huanan market, including some species already involved in the 2002–2004 SARS epidemic (X. Xiao et al., 2021; Crits-Christoph, Levy, et al., 2024; W. J. Liu, P. Liu, et al., 2024). The stalls selling these animals were located in the southwest corner of the west wing of the market (G. Wu, 2020; World Health Organization, 2021), which was a hotspot of SARS-CoV-2 positivity (Worobey et al., 2022). Genetic material from both SARS-CoV-2 and from key animal species such as raccoon dogs and civets was detected in samples from the same stall (Crits-Christoph, Levy, et al., 2024).

Epidemiological and genomic data point to the Huanan market. (A) Locations of the residences of Covid-19 cases with symptom onset in December 2019 (gray dots). The green star is the mode of the distribution of cases (i.e., the location of the peak of a kernel density estimate of case residential locations, computed as in Débarre and Worobey (2024a)). Shown are the locations of the Huanan market (red square), and of the two campuses of the Wuhan Institute of Virology: the historical campus in Wuchang district (light pink), and the more recent campus in Jiangxia district (dark pink), where the biosafety level 4 (BSL4) laboratory is located. Case data from World Health Organization (2021), extracted by Worobey et al. (2022), updated with Hubei cases outside of Wuhan; figure adapted from Débarre and Worobey (2024a). (B) Zooming in on map A near the market, showing two additional landmarks: the Hankou railway station (olive green triangle) and the new location of Wuhan CDC (orange diamond). (C) Phylogeny of early SARS-CoV-2 sequences, showing the two main early lineages, A and B. Figure adapted and updated from Crits-Christoph, Levy, et al. (2024) following the removal of duplicates and new annotations identified by Hensel and Débarre (2025). Sequences linked to the market are shown in red; dark red is for geographic links (spatial proximity) to the market.

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 shows similarities with the emergence of SARS-CoV, 17 years prior (Holmes et al., 2021; Pekar, Lytras, et al., 2025). Infected animals were detected in a market in Shenzen, in Guangdong Province, in May 2003, i.e., months after the emergence of SARS-CoV (Y. Guan et al., 2003). This led to a ban on wildlife trade, which was lifted in the summer 2003 (Normile and Yimin, 2003; P. Li, 2020), and sampling in the Fall that year, in the same market, found again SARS-CoV-positive animals: civets, raccoon dogs, ferret badgers, hog badgers, and badgers (Y. He, 2004). Animals were also directly identified as infection sources in a later resurgence of the virus in Guangzhou, still in Guangdong Province, in late 2003 (M. Wang et al., 2005). The exact details of how originally SARS-CoV emerged in 2002 are however still unknown; the specific animals that led to those early infections in 2002 were not identified (R.-H. Xu et al., 2004). Yet, in spite of this uncertainty, and for lack of a reasonable alternative explanation, there is a strong consensus that SARS-CoV was of zoonotic origin, and that it was transmitted to humans via intermediate host(s) in the wildlife trade (Cui et al., 2019). New data and analyses have continued to improve our understanding of how sarbecoviruses diversify and spread in bats (Pekar, Lytras, et al., 2025).

Shortly after the emergence of SARS-CoV, two new coronaviruses infecting humans were identified: NL63, an alphacoronavirus first detected in the Netherlands (van der Hoek et al., 2004), and HKU1, a betacoronavirus first detected in Hong Kong, in a patient with pneumonia who had recently returned from Shenzhen (Guangdong; China) (Woo et al., 2005). Related viruses have been detected in bats (NL63) and rodents (HKU1) (Corman et al., 2018), but the exact details of the emergences of these two coronaviruses, now endemic in humans, are unknown—including the identities of potential intermediate hosts between their putative reservoirs and humans (Holmes, 2024). Yet, the zoonotic origins of these coronaviruses are not called into question.

The zoonotic origin of SARS-CoV-2, on the other hand, is contested (e.g., Bloom et al., 2021; Van Helden et al., 2021; Berche, 2023). Research-related origin scenarios (Van Helden et al., 2021) are supported by the presence in Wuhan of virology laboratories, with one in particular studying SARS-like coronaviruses, and by apparently unique properties of SARS-CoV-2 not observed in the known related viruses. Unlike the examples of previous emergences given above, here, there was a credible non-zoonotic alternative origin of SARS-CoV-2. Apparently unique molecular features of SARS-CoV-2 have been scrutinized since the beginning of the pandemic, and the possibility of a research-related origin has therefore been seriously considered early on (Andersen et al., 2020).

“Research-related origin”, often simplified as “lab leak” in the public discourse, is an umbrella term encompassing a diversity of scenarios, which will be detailed in the first part of this review. The second part will focus on a specific element that is prominently featured in discussions of a potential research-related origin, namely the presence in SARS-CoV-2’s spike of an insert that encodes a functional furin cleavage site. We will see in particular how the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 over the last five years has informed the plausibility of a natural origin of this insertion.

Finally, while the discussion of the potential origins of SARS-CoV-2 is a valuable academic exercise, it is important to keep in mind that some research-related origin theories implicate specific, identifiable researchers as responsible for the Covid-19 pandemic, and that such serious and consequential accusations should be based on evidence, not just speculation.

2. A typology of SARS-CoV-2 research-related origin scenarios

Multiple scenarios can be described as corresponding to a research-related origin. Here, we attempt to classify them exhaustively by considering five factors. Two factors correspond to intrinsic characteristics of the virus: (A) the nature of the virus (natural or synthetic to some degree), (B) the location of its origin. Three other factors correspond to features of the first human infections by SARS-CoV-2 that led to the Covid-19 pandemic: (C) the location, (D) type (accidental or not), and (E) timing of these first human infections. The proposed classification is such that an origin scenario is constructed by choosing a single option in each of the six categories. We will see that some combinations of options are not possible. The various options are recapitulated in Table 1.

Exhaustive list of options for research-related origins of SARS-CoV-2 (tentative)

| Category | Options |

|---|---|

| A. Nature of the virus | A.1 Fully natural |

| A.2 Research product; Undirected evolution | |

| A.3 Research product; Directed evolution | |

| A.4 Research product; Genetic engineering | |

| A.5 Some combination of A.2, A.3, A.4 | |

| B. Location of the origin of SARS-CoV-2 | B.1 Outside of a research site |

| B.2 Fieldwork site | |

| B.3.a WIV, Wuchang campus, BSL2 lab | |

| B.3.b WIV, Wuchang campus, BSL3 lab | |

| B.4.a WIV, Jiangxia campus, BSL2 lab | |

| B.4.b WIV, Jiangxia campus, BSL3 lab | |

| B.4.c WIV, Jiangxia campus, BSL4 lab | |

| B.5.a Wuhan CDC, Dec 2019 location near market | |

| B.5.b Wuhan CDC, old location | |

| B.6 Other lab in Wuhan | |

| B.7 Other lab in China | |

| B.8 Lab outside of China | |

| C. Location of first infections | (Same options as B.) |

| D. Type of first infections | D.1 Accidental |

| D.2 Deliberate but non malicious | |

| D.3 Deliberate and malicious | |

| E. Timing | Specified time (until December 2019) |

In each category, only one option can be chosen to build a research-related origin scenario.

2.1. (A) Nature of the virus

SARS-CoV-2 is either a natural virus, that evolved via natural selection, or a virus modified to some degree in a laboratory. Evolution in a lab can be accidental, e.g., a side-effect of isolation. For instance, isolation of a SARS-CoV-2-related pangolin coronavirus (GX_P2V) was accompanied by a 104-nucleotide deletion, that led to attenuation in cell culture and in vivo (S. Lu et al., 2023). Isolation and culture of WIV1 from bat SARS-like coronavirus Rs3367 (Ge et al., 2013) resulted in two amino-acid changes in its spike, one of which was shown to increase the virus’s ability to bind to the cell receptor ACE2 and was interpreted as an adaptation to cell culture (Tse et al., 2025). Evolution can be directed, for instance in the context of serial passage. In serial passage experiments, pathogens are transferred from one host to another (usually of the same species; the host can be from an experimental animal to a cell culture), which can lead to adaptation to the host on which the pathogen is passaged (Ebert, 1998); mutations arise spontaneously, but their selection is artificial. For instance, SARS-CoV-2 was adapted to mice in order to generate laboratory models, as the original version of the virus did not interact well with the mouse ACE2 receptor (P. Zhou et al., 2020). Serial passage on mice led in particular to a substitution in the receptor binding domain of the spike, N501Y (Gu et al., 2020), which later appeared in variants of concern like Alpha and Omicron. Finally, SARS-CoV-2 can be the product of direct genetic engineering: here, the mutations are planned and deliberately introduced by researchers. For instance, another mouse-adapted version of SARS-CoV-2 was generated by reverse genetics after introducing two substitutions predicted to be key for interaction with the mouse ACE2 receptor (Dinnon et al., 2020). It is also possible to envision combinations of different options, for instance genetic engineering of a previously serially-passaged virus (see Table 1).

The possible nature of the virus may be informed by the location where it is assumed to have emerged. For instance, location is the main characteristic to differentiate a natural virus from a virus generated by undirected evolution in a lab, as the two may be barely distinguishable at the sequence level. Also, a genetically engineered virus is only possible in a laboratory with the capability to conduct genetic engineering of viruses. In other words, following our classification attempt (Table 1), the selection of a given option for one factor may affect the range of possible options for others.

Scenarios involving virus manipulation in the lab (directed evolution, genetic engineering, and combinations thereof) require the knowledge and possession by the researchers of a virus that serves as progenitor. If SARS-CoV-2 is assumed to be chimeric, more than one progenitor is required. A virus of natural origin, on the other hand, also has a direct progenitor, but us knowing or not the identity of the progenitor is not a limitation, because evolution occurred without human intervention. To date, no known virus could have served as progenitor of SARS-CoV-2 (Andersen et al., 2020). The closest known cousins, RaTG13 and then BANAL viruses, are too distant from SARS-CoV-2 across the whole genome to be its progenitor (P. Zhou et al., 2020; Temmam et al., 2022). After delimiting non-recombining regions in SARS-CoV-2’s genome, the closest relatives vary across regions: SARS-CoV-2’s genome is a mosaic (Boni et al., 2020; Pekar, Lytras, et al., 2025). Lab manipulation scenarios therefore imply the existence of viruses kept secret—for which there is, to date, no evidence. If it were possible to definitely demonstrate the absence of such progenitors in the Wuhan laboratories, the discussion would stop here. Conversely, if the existence of such a progenitor in the collections of a laboratory were discovered, a lab origin would immediately become much more likely. We therefore still consider these scenarios here, keeping in mind the fundamental limitation that they require a virus that would have been kept secret.

The possible nature of the virus may also be informed by its genomic sequence. The assembly of a full viral genome from smaller fragments may or may not leave traces (Almazán et al., 2014). These techniques may use Type IIS restriction enzymes, which cleave outside of their recognition sequences and leave overhangs. Depending on the orientation of the restriction sites, those may be retained in the assembled product, or removed (Almazán et al., 2014; Yount et al., 2002; H.-L. Cai and Y.-W. Huang, 2023) (see Figure S1). Seamless techniques leave no trace and are therefore not detectable, unless a marker like a silent point mutation is deliberately introduced (Hou et al., 2020). Traditional cloning methods, on the other hand, leave traces in the form of restriction sites. However, because they consist of short nucleotide sequences, restriction sites may also be present by chance. SARS-CoV-2’s genome contains several restriction sites; they are not regularly spaced and are found in related viruses, i.e., they are consistent with a natural origin (Crits-Christoph and Pekar, 2022).

Beyond the technique to generate a potential genetically engineered virus, genetic engineering could be identified by the presence of unnatural-looking segments. Suspicions of unnatural-ness are at the core of claims of genetic engineering, since the early, quickly rebutted and withdrawn, suggestion that SARS-CoV-2 may contain fragments from HIV (Pradhan et al., 2020; Sallard et al., 2021). In Section 3, we will explore in detail the claim that SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site was inserted in a laboratory.

The claim that SARS-CoV-2 may have been generated in a laboratory also stems from the observation that SARS-CoV-2 seemed to be efficiently transmissible from human to human early on (Zhan et al., 2020), leading to the suggestion that it may have been somehow pre-adaptated in a laboratory. SARS-CoV-2 is however a generalist virus; it transmitted well from human to human, but could also readily infect other mammals. Notably, it caused outbreaks in mink farms early on (Oude Munnink et al., 2021), without having been pre-adapted to minks in a laboratory. Pre-adaptation may simply be a consequence of the fact that mammals, including humans, share similar features. For instance, a recently discovered MERS-like coronavirus infecting minks in China (J. Zhao et al., 2024) was shown to replicate in cells expressing receptors from minks, but also humans and even camels (N. Wang et al., 2025). In addition, SARS-CoV-2 was not perfectly adapted humans: further adaptations took place, in particular the D614G mutation in the spike. This mutation stabilized the spike, preventing premature shedding of the S1 domain (J. Zhang et al., 2021; Choe and Farzan, 2021), thereby increasing SARS-CoV-2’s infectivity (Korber et al., 2020). Detected as early as January 2020 in patients from China (Böhmer et al., 2020; Lv et al., 2024), the D614G mutation spread across the world and became dominant. The same mutation later convergently occurred in lineage-A viruses (Murall et al., 2021), before the lineage went extinct.

Finally, SARS-CoV-2 is a pandemic virus, and pandemics are rare; SARS-CoV-2 is necessarily an extra-ordinary virus, as were previous pandemic viruses, including those that emerged before the advent of modern virology: a laboratory origin is not a necessity to explain SARS-CoV-2’s rapid spread in the human population. Features that brought a selective advantage in humans to the viruses possessing them—such as the furin cleavage site—spread better and could be naturally selected.

2.2. (B) Location of the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, and (C) location of the first human infections

We now consider is the location where the virus would have been generated, and where the first humans were infected. Under most research-related origin scenarios, the two locations are the same. Discrepancies may however exist in the case of a release linked to a vaccine challenge, or in the case of a virus generated elsewhere and then shipped to Wuhan.

A research-related incident could have happened in nature, with a natural virus, in the context of fieldwork. First infections outside of a laboratory may also happen in the context of a vaccine challenge, as will be detailed below.

Various laboratories have been considered as potential locations of the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. The most frequently mentioned one is the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV), located across two campuses: a campus in Wuchang district, and south of it, a campus in Jiangxia district, where the BSL4 lab is located (Figure 1A). The BSL4 lab was the first of its kind in China (Yuan, 2019). Coronaviruses are not typically manipulated in BSL4 conditions, but rather BSL3 or BSL2 depending on the type of coronavirus (CDC, 2020) and type of experiment, so the presence of a BSL4 laboratory in Wuhan is coincidental. The use of a BSL4 laboratory depends on local regulations, and may not be aligned with the wider public’s perception of danger; for instance, reconstruction of 1918 pandemic influenza virus (Tumpey et al., 2005), or experiments resulting in airborne transmission of H5N1 between mammals (Herfst et al., 2012), did not take place at BSL4 but BLS3. When the Wuhan BSL4 laboratory was put in operation, however, “low pathogenic coronaviruses” were used there as model viruses by researchers for training (Cohen, 2020). Yet, discussions of a potential research-related origin most often envision experiments carried out at a biosafety level that some deem insufficient for viruses with uncertain potential for human infection and onward transmission, namely BSL2 (e.g., A. Chan, 2024). Under such a scenario, Wuhan is not an exceptional location: BSL2 laboratories are common.

Another Wuhan laboratory considered among the possible locations of emergence of SARS-CoV-2 is the Wuhan Center for Disease Control (WCDC). WCDC moved next to the Huanan market in late 2019 (World Health Organization, 2021), and was mentioned in one of the early public prepublications naming specific laboratories as potential origins (B. Xiao and L. Xiao, 2020). Pre-Covid-19 research from WCDC featuring the researcher targeted by scenarios involving this institution (B. Xiao and L. Xiao, 2020; Tufekci, 2021), was not on coronaviruses (Guo et al., 2013; M. Lu et al., 2017; Shi et al., 2018). Even a December 2019 promotional video put forward in WCDC scenarios to incriminate the researcher and his bat-sampling activities (Tufekci, 2021), featured the collection of ticks from bats (China Science Communication, 2019), indicating a focus on other types of pathogens. WCDC had been involved in the collection of samples, including from bats, but did not have the facilities to conduct actual experiments and even less so for genetic engineering (Holmes, 2024). If SARS-CoV-2 came from WCDC, it is therefore a natural virus brought to the laboratory, and not an engineered virus for instance. Using nomenclature from Table 1, options A.4 and B.5 are therefore incompatible.

Wuhan hosts other research laboratories that could potentially be other locations of emergence. Research on coronaviruses was for instance also carried out at Huazhong Agricultural University in Wuhan (Shen et al., 2018). The labs had, to our knowledge, no history of experimenting on SARS-like coronaviruses, and they do not have a geographic association with early cases. Likewise, Chinese laboratories outside of Wuhan will not be further considered here, although their implication has sometimes been suggested, e.g. for researchers in Beijing (Kadlec, 2024).

There have also been suggestions that SARS-CoV-2 could have been conceived and even generated in a laboratory outside of China, and sent to Wuhan. One of these scenarios involves a North Carolina research laboratory that collaborated with WIV (Harrison and Sachs, 2022; Kosubek, 2025). Other scenarios, as mirrors of accusations targeting Wuhan’s BSL4 laboratory, implicate Fort Detrick in the United States (Y. Huang and Best, 2024) and remove any link to a Wuhan laboratory. By getting rid of any geographical link, such scenarios could implicate virtually any virology laboratory in the world, and will therefore not be further considered here.

Case data can inform on the geographic location of the first infections that lead to the Covid-19 pandemic. The outbreak was first identified in December 2019 because of clusters of patients suffering from pneumonia, linked to the Huanan market, seeking care in several Wuhan hospitals (Worobey, 2021; D. L. Yang, 2024). Available case data, compiled retrospectively, show that the earliest human cases were centered around the Huanan market, whether they were epidemiologically linked to it or not (Worobey et al., 2022; Débarre and Worobey, 2024a; Débarre and Worobey, 2024b). Similar patterns were observed for infections of healthcare workers (P. Wang et al., 2021). Except for a scenario involving WCDC, which had moved close to the Huanan market in late 2019, research-related scenarios fail to provide explanations for this striking spatial pattern. The Huanan market is indeed not just any location in Wuhan: it was one of the only four markets reported to sell live wildlife, and the one with the largest number of wildlife stalls among them (X. Xiao et al., 2021). This is a least a striking coincidence that deserves to be accounted for, whatever the proposed scenario for the origin of SARS-CoV-2.

2.3. (D) Type of first infections

Three types of first human infections in a research-related context can be distinguished. First, the first human infections may have been accidental. Secondly, they may also have been deliberate, but not necessarily in a nefarious context, e.g., a vaccine challenge. While little discussed in the context of SARS-CoV-2 (for lack of any evidence supporting the scenario), this type of release is listed here as option because it is considered a plausible origin of 1977 H1N1 influenza (Rozo and Gronvall, 2015). Such a release cannot adequately be described as “lab leak”, because the virus is deliberately taken out of a laboratory. (Note that this category describes the type of first human infections and not the context of the research; accidental infections of researchers working on the design of a vaccine would be characterized as accidental first infections.) Finally, a last type of first human infections is deliberate with malicious intent (Nilsen et al., 2022), like the release of a bioweapon. Like the second type, it would not be described as a “leak”. This option is listed here in order to be exhaustive, but is completely unsupported (Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI), 2021).

2.4. (E) Timing of the first human infections

The known cases who reported the earliest symptom onset started to feel sick around December 10–11, 2019 (Worobey, 2021). These early cases were however likely not the first infections. Attempts to date the first infections, using either only case data (Jijón et al., 2024), or a combination of case data and genomic sequences (Pekar, Magee, et al., 2022), converge towards first infections from late October to early December, with a median in the second half of November 2019.

Research-related origin scenarios consider a whole range of possible dates of first infection, sometimes contradictory, depending on the external events considered to the major drivers or signs. These external events include for instance (Kadlec, 2024): the (actually only temporary at the time) shutdown of a database at WIV in early September 2019; a security exercise at Wuhan airport, simulating infections by a new coronavirus, mid-September 2019; the 2019 Military World Games in Wuhan in the second half of October 2019; a yearly training in WIV’s BSL4 laboratory in the second half of November 2019; alleged infections of WIV scientists in November 2019 (Cohen, 2023), etc. Some of these events are at odds with the estimated dates of first human infections, and even lead to temporally impossible scenarios. For instance, the pandemic cannot have started with infections of scientists in November 2019 and, in the same scenario, have spread throughout the world via the Military Games in October 2019.

We tried here to provide an exhaustive list of the different elements composing a scenario SARS-CoV-2’s origin, detailing research-related origins. Importantly, the accumulation of possible research-origin scenarios, sometimes put forward to arouse suspicion (Tufekci, 2021), does not necessarily increase the likelihood of a research origin, especially when the proposed scenarios are mutually contradictory. Arguments about research done at BSL2 are irrelevant in a scenario involving the BSL4 lab, and reciprocally; descriptions of personal protective equipment by researchers doing fieldwork are irrelevant in a scenario of a lab-engineered virus. Making explicit the envisioned scenarios—which is rarely done—helps see their potential logical flaws.

We now focus on a specific feature of SARS-CoV-2, its furin cleavage site, and on the suggestion that it could have been the product of deliberate genetic engineering.

3. Dissecting a particular scenario: the insertion leading to the furin cleavage site

The spike of coronaviruses is cleaved into S1 and S2 subdomains to mediate fusion with the host cell membrane (Millet and Whittaker, 2015). Spike cleavage can occur at different stages of the infection cycle, depending on the virus and host cells (ibid.): during the production of new viruses in the producer host cell; in the extra-cellular space; at the surface of target cells; in lysosomes after endocytosis in target cells (F. Li, 2016). The presence of a polybasic cleavage site allows the spike protein to be cleaved by host enzymes like furin in the producer cell, so that the spike is already primed when a target cell is later encountered.

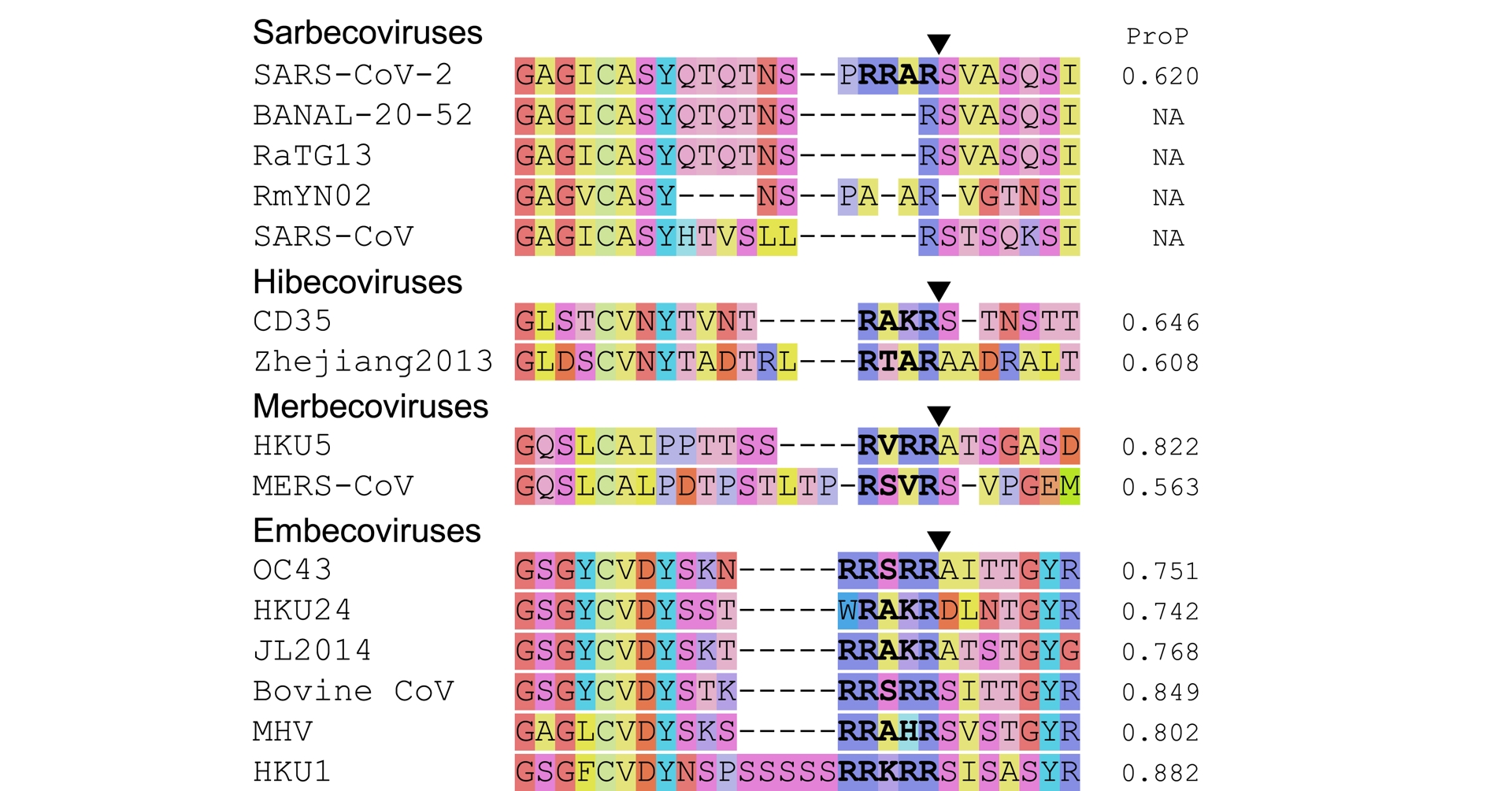

Multiple betacoronaviruses have a polybasic cleavage site at the S1/S2 junction, including human pathogens like MERS-CoV, HKU1, OC43 (Y. Wu and S. Zhao, 2021; Holmes et al., 2021, Figure 2). Polybasic cleavage sites have repeatedly evolved through the history of coronaviruses.

SARS-CoV-2’s polybasic cleavage site is a unique feature among known sarbecoviruses, but not among other betacoronaviruses. The black triangles locate the cleavage sites; here and in the other figures, the triangles are not repeated within alignments. Polybasic sites are highlighted in boldface. The color palette is borrowed from Nextclade (Aksamentov et al., 2021); colors depend on chemical properties. The right column shows the predicted score according to ProP (Duckert et al., 2004); a score above 0.5 corresponds to a predicted polybasic cleavage site. Figure adapted from Holmes et al. (2021), updated with examples from Han et al. (2023, Figure S7) and W. Zhu et al. (2023). Accessions of the sequences are provided in the Methods section.

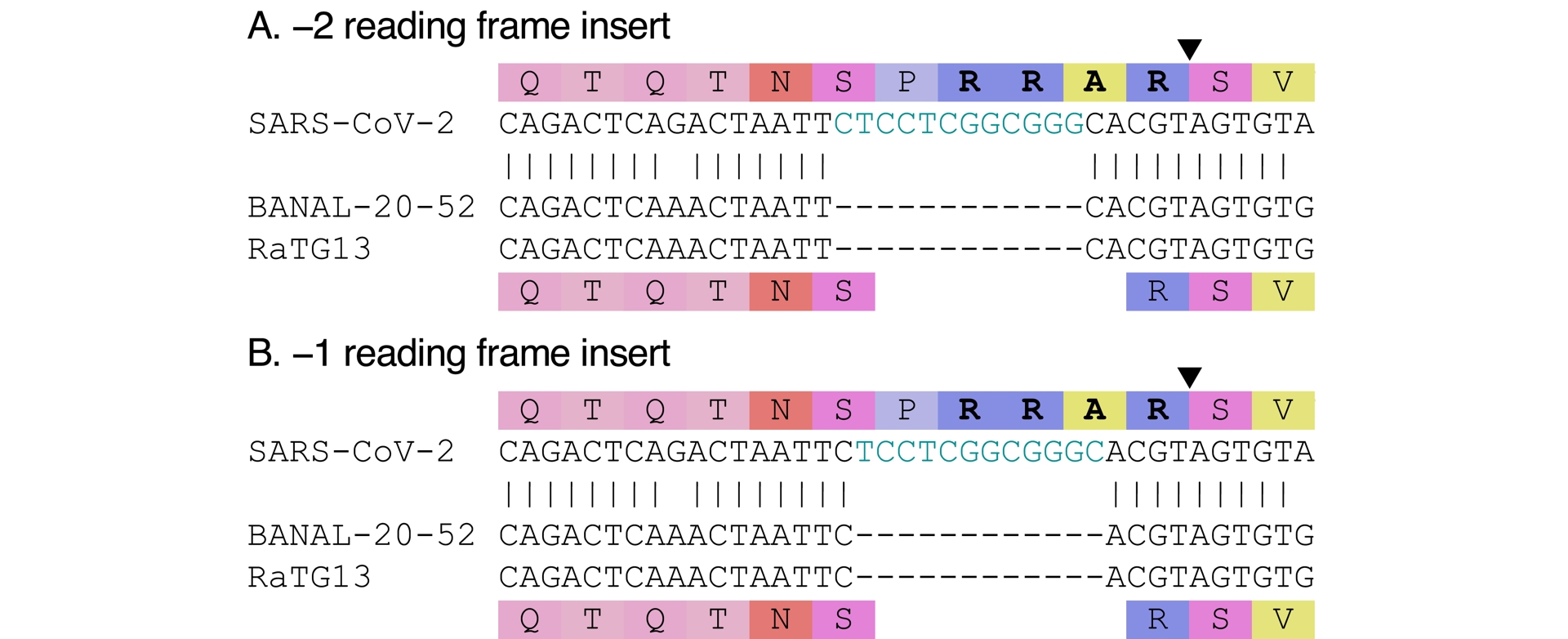

While a polybasic cleavage site is not an uncommon feature among the Betacoronavirus genus, SARS-CoV-2 is the first known sarbecovirus (Coutard et al., 2020), and to date the only one, that possesses one at the S1/S2 junction. This feature has been shown to contribute to its replicability in host cells (Hoffmann et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2021) and its transmissibility among hosts (T. P. Peacock et al., 2021). The known related sarbecoviruses are devoid of a furin cleavage site. SARS-CoV, notably, does not have one—which, incidentally, illustrates that a furin cleavage site is not essential for respiratory infections, nor for human to human transmission to take place. Compared to related sarbecoviruses, SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site appears to have been introduced via an out-of-frame insertion (see Figure 3). Four amino acids (PRRA) inserted near the S1/S2 cleavage site contribute to forming a RXXR-type furin cleavage site (where X is any amino acid). The rarity of furin cleavage sites among sarbecoviruses, and the fact that it is formed by a 12-nucleotide insertion compared to the most closely related viruses, have led to the suggestion that the insertion could have been artificial.

SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site is caused by an insertion compared to its closest known relatives. The insert is shown in blue in the nucleotide sequence (two inserts are possible); it leads to a furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 (shown in boldface in the amino acid sequence), but also adds a leading proline (P). The black triangle locates the cleavage site (shown only once for each alignment group). Compared to the known viruses, the insert is out of frame. Because of the “C”s at each end, both a −1 and a −2 out of frame inserts are possible.

3.1. The features and originalities of SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site are consistent with natural evolution

The repeated evolution of furin cleavage sites in other coronaviruses indicates that this feature can evolve naturally. The furin cleavage sites in other coronaviruses are diverse, yet none seems to exactly match SARS-CoV-2’s, at the amino acid level, and even less so at the nucleotide level. The original insert in SARS-CoV-2 introduced a leading proline (P) that was not part of the polybasic site—but became as the position mutated throughout SARS-CoV-2’s evolution (it mutated into a histidine [H] in Alpha, Omicron BA.1, 2, and more so when it mutated into an arginine [R] in Delta and BA.2.86; see Figure S2). Although a similar proline (P) happens to be present in MERS-CoV (see Figure 2), its function was not described as part of the polybasic site (Millet and Whittaker, 2014) nor as critical to it, and therefore as necessary in an artificial insertion. Instead, this is the kind of superfluous-looking element that occurs randomly.

The progenitor virus just before SARS-CoV-2 (whether it evolved naturally or not) is unknown; we can therefore only describe SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site in relation to the other known close relatives. It is however possible that the progenitor sequence was different, which would affect the estimated length and position of the insert. In particular, it is possible that an insert was already present, and SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site evolved by mutation of that previously inserted, different sequence (Morgan et al., 2025). Absent any information on the progenitor sequence, we assume that comparison to close relatives is representative of what actually happened. Compared to close relatives, then, the insert is out of frame (both −1 and −2 positions are possible; see Figure 3). There would be no rationale for doing an out-of-frame insertion in the lab instead of a regular in-frame insertion; this is the kind of detail that makes the insert look natural rather than engineered.

The two arginines (RR) in the original insert were both encoded by CGG, leading to a CGGCGG suite of nucleotides. Codon usage bias in related coronaviruses is such that R is rarely encoded by CGG; the occurrence of a double CGG is therefore an oddity. Yet, this oddity is still largely present among SARS-CoV-2 sequences. Although mutations have been detected at each position of the fragment, the original nucleotides are still present in 99.9% of all sequences (as of August 2024 (C. Chen et al., 2022)), with the most variation present at the third position of the first codon of the pair (T present at 0.1%). In other words, regardless of how bizarre it looked, CGGCGG has not yet been purged by selection in SARS-CoV-2.

In humans, CGG is a frequent codon for R, which has led to the suggestion that CGGCGG was a tell-tale sign of engineering (Segreto and Deigin, 2021; Wade, 2023). We now explore in detail this suggestion.

3.2. CGGCGG is not evidence of engineering

The rationale behind the suggestion that CGGCGG may be the sign of engineering is that is would reflect codon optimization by a genetic engineer for expression in humans. CGG would have been chosen, twice, because it is the most frequent codon encoding arginine (R) in humans. All elements of the proposition are incorrect.

CGG is not the sole frequent codon for arginine in humans, nor is it specific to humans. Whether CGG is the most frequent or one of the most frequent depends on the databases considered (e.g. Genscript vs. “Kazusa” http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/). Other codons, AGA, AGG and CGA are also frequent (listed in decreasing order). There is therefore no rationale for selecting CGG twice rather than combining it with other frequent codons. In addition, codon usage bias is such that CGG is also frequent in other mammals. It is for instance the most frequent for arginine (R) in cows (Bos taurus in the Kazusa database). The high frequency of CGG is therefore not specific to humans, and the presence of CGG would not be evidence of artificial adaptation to humans specifically.

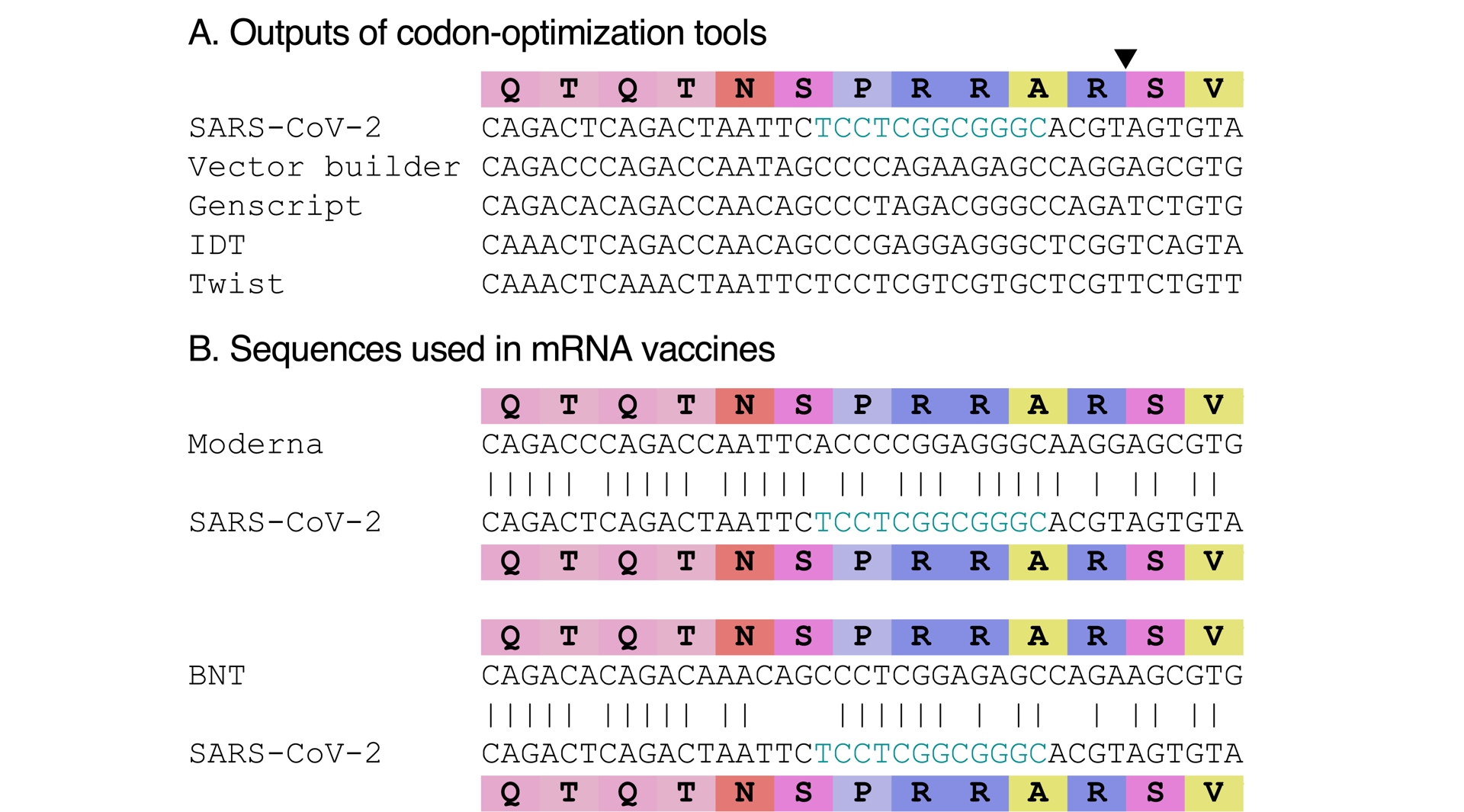

Codon optimization refers to the use of synonymous codons to increase protein expression (Mauro and Chappell, 2014) while ensuring sequence stability. There would be no reason, and it would be inefficient, to only codon-optimize two codons (or four) in SARS-CoV-2’s genome. In addition, codon optimization is not done by hand by selecting the most frequent codons for translation in a choice organism. Software exists to carry out the task, and they try to avoid too high CG content. To demonstrate that CGGCGG would not actually be the result of codon optimization for humans, we submitted the QTQTNSPRRARSV amino acid sequence to various free online codon-optimization tools, for expression in Homo sapiens, with default settings. None of them proposed CGGCGG for RR (Figure 4A). In addition, there exist examples of sequences that were actually codon-optimized for humans, notably with the sequences of the mRNA vaccines. Again, neither of them used CGGCGG for RR (Figure 4B). Last but not least, if codon optimization had actually taken place to generate a virus, one may have expected it to be codon-optimized as a human coronavirus, not as a human sequence. That the double arginine (RR) in SARS-CoV-2’s polybasic site is encoded by CGGCGG is therefore rather a counter-argument to the claim that it might be engineered.

CGGCGG is not a codon-optimized encoding of RR. The black triangle locating the cleavage site is shown only once. (A) Sequences obtained via various online codon-optimization tools for the shown amino-acid sequence. The URLs of the various tools are given in the Methods section. (B) Sequence fragments from mRNA vaccines, Moderna (top) and Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT; bottom).

3.3. Previous experiments did not insert a furin cleavage site

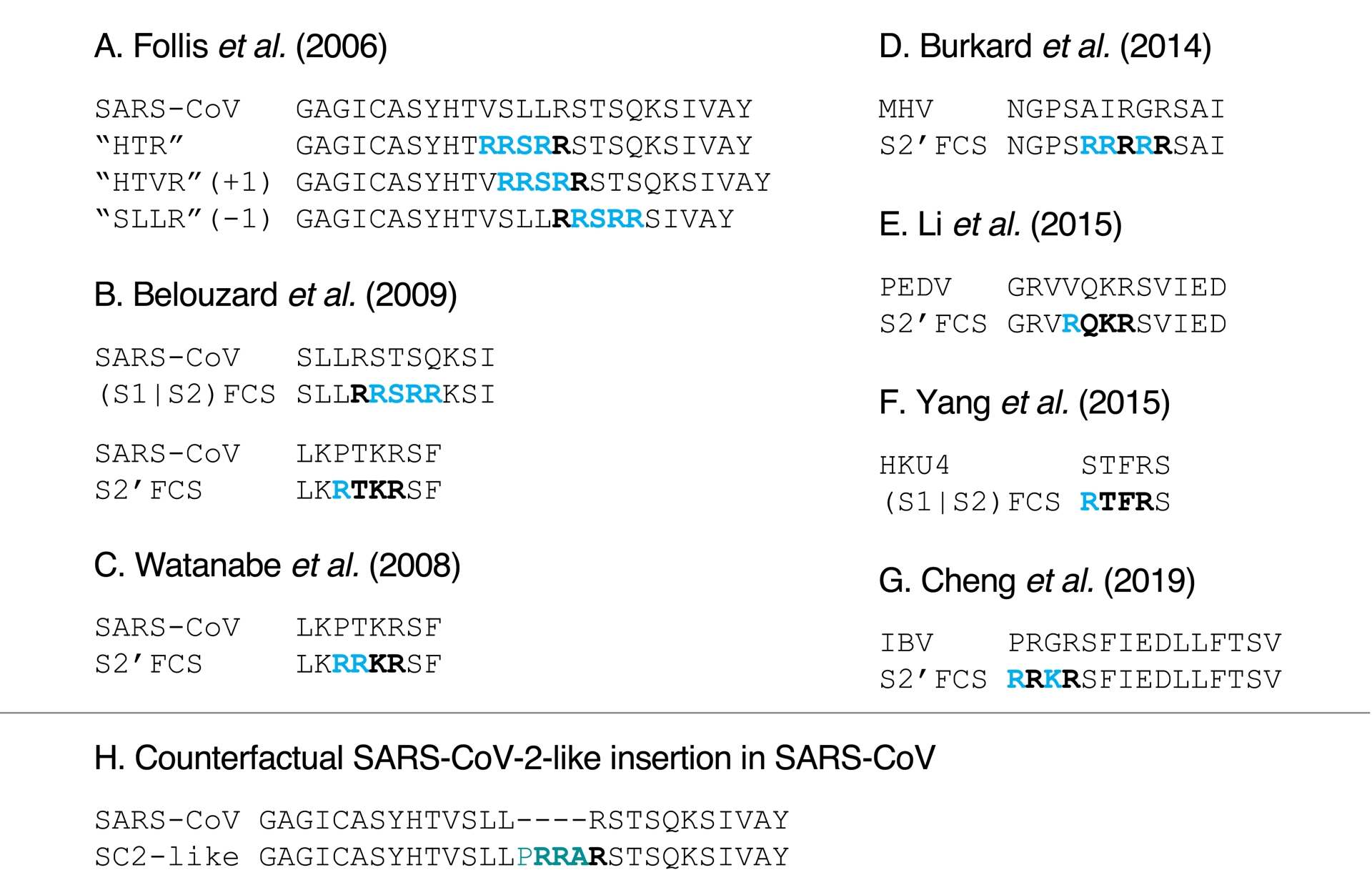

The suggestion that SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site could have been engineered also uses the argument that such manipulations had been done on coronaviruses before the Covid-19 pandemic (Follis et al., 2006; Belouzard et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2008; Burkard et al., 2014; W. Li et al., 2015; Y. Yang, C. Liu, et al., 2015; Cheng et al., 2019) (albeit, especially in the case of experiments on SARS-CoV, with pseudotypes and not live virus). The experiment was described as “routine” in arguments for an artificial origin of the insert (A. Chan and Ridley, 2021), while the number of studies was in fact very limited—less than ten were found on coronaviruses.

Closer inspection of the details of these experiments reveals that the introductions of furin cleavage sites were done very differently from how SARS-CoV-2’s is proposed to have been generated. As described above, compared to its known close relatives, SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage emerged by the insertion of 12-nucleotide sequence, encoding four amino acids (PRRA), including one (P) that was originally not part of the polybasic site. Previous experiments, on the other hand, did not introduce polybasic sites via such a large insertion, but instead did so by modifying existing sequences in place by point mutations (Figure 5A–G; occasionally removing or adding one amino acid, see Figure 5A). In addition, except when the mutations were meant to match another close coronavirus (changing HKU4’s sequence to resemble MERS-CoV’s (Y. Yang, C. Liu, et al., 2015, Figure 5F)), the introduced cleavage sites were canonical, i.e., R-X-(R/K)-R (where X is any amino acid), instead of the minimal R-X-X-R version found in SARS-CoV-2. Importantly, none of these experiments introduced amino acids outside of the polybasic site, unlike SARS-CoV-2’s leading proline (P). Even the experiment on HKU4, designed to resemble MERS-CoV’s polybasic site, did not introduce a proline (P), while there is one in MERS-CoV before its polybasic site (compare Figure 2 and Figure 5F). Figure 5H illustrates what an experiment on SARS-CoV matching SARS-CoV-2’s insertion would have looked like. Moreover, experiments with SARS-CoV (Follis et al., 2006; Belouzard et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2008) (and HKU4 (Y. Yang, C. Liu, et al., 2015)) were done with pseudotypes, not full viruses. These previous experiments are therefore actually arguments against an artificial origin of the 12-nucleotide insert in SARS-CoV-2.

Pre-2020 experiments introducing a polybasic cleavage site in coronaviruses (A–G), and counterfactual equivalent of SARS-CoV-2’s insertion in SARS-CoV (H). (A–G) The mutated positions are colored in blue and the resulting polybasic cleavage sites are highlighted in boldface. The polybasic segments were introduced by mutating the sequences in place, occasionally adding or removing one amino acid. (A) Follis et al. (2006), on SARS-CoV. (B) Belouzard et al. (2009) on SARS-CoV, at S1/S2 and at S2′ (the S1/S2 alignment shown here includes a K that seemed to have been accidentally missing in the original paper). (C) Watanabe et al. (2008), on SARS-CoV at S2′. (D) Burkard et al. (2014), on mouse hepatitis coronavirus (MHV), a betacoronavirus, at S2′. (E) W. Li et al. (2015), on porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV), an alphacoronavirus, at S2′. (F) Y. Yang, C. Liu, et al. (2015), on HKU4 (related to MERS-CoV), at S1/S2 to resemble MERS-CoV’s minimal furin cleavage site RSVR. (G) Cheng et al. (2019), on Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), a gammacoronavirus, at S2′. (H) Counterfactual SARS-CoV-2-like insertion at S1/S2, not performed by the authors of Follis et al. (2006), Belouzard et al. (2009), but similar to what the PRRA insert does to SARS-CoV-2 (inserting several amino-acids instead of mutating in place; adding a leading proline P).

3.4. Proposed engineering scenarios

SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site is non-canonical (Thomas, 2002). Besides its leading proline, discussed above, the polybasic site itself is minimal and does not match classical sites in other coronaviruses. It also does not match the RRSRR site introduced in SARS-CoV in previous experiments (Follis et al., 2006; Belouzard et al., 2009, Figure 5A, B). It is hard to explain why PRRA would have been inserted, and not some more commonly known polybasic site. Several post-hoc explanations were proposed for the choice and source of a PRRA insertion, that we now detail.

3.4.1. HIV-1

In late January 2020, a preprint claimed to have identified four insertions in SARS-CoV-2’s genome (Pradhan et al., 2020); the fourth one contained the insertion that introduced the furin cleavage site. Searching for the potential sources in genomic databases, the authors (ibid.) claimed that the inserts may be coming from HIV-1. The preprint, which went viral on social media (Altmetric, 2025), was quickly rebutted, and it was withdrawn a few days later. First, the authors had mischaracterized the four inserts because of improper sequence alignments; second, the matches with HIV-1 were not statistically significant (Sallard et al., 2021). In other words, the matches were simply the product of chance.

3.4.2. Moderna patent sequence

Searching for the 12-nucleotide insert in genomic databases also revealed that a similar sequence was present, as reverse complement, in a 2016 patent by Moderna (Bancel et al., 2017) (a biotechnology company that developed one of the mRNA Covid-19 vaccines in 2020). In addition to its lack of functionality in its original context, the sequence was, once again, shown to be a coincidence (Dubuy and Lachuer, 2022).

3.4.3. ENaC-𝛼

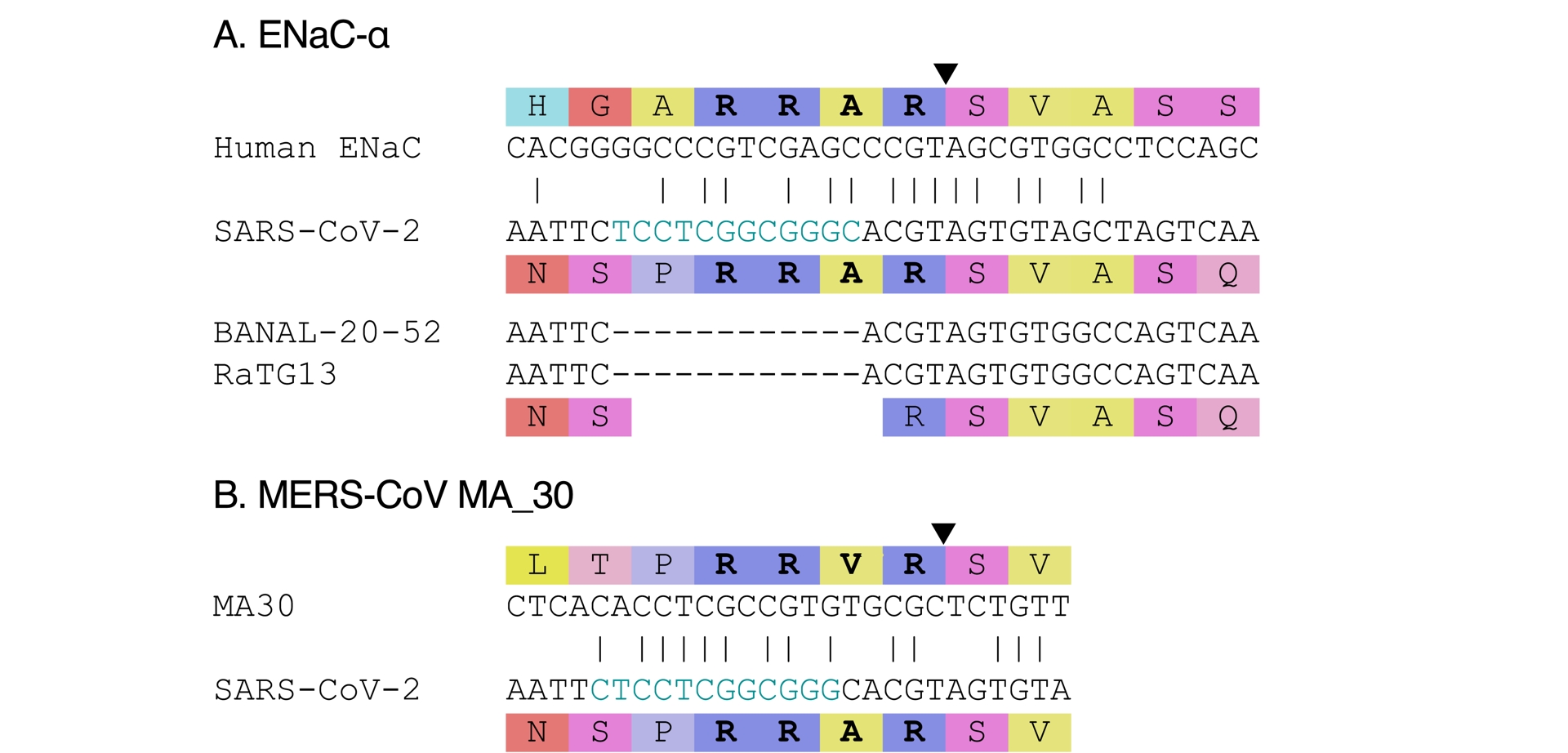

The amino-acid sequence of SARS-CoV-2 at its furin cleavage site and a few positions beyond had been shown to match the amino-acid sequence of a human epithelial channel protein called ENaC-𝛼 (Anand et al., 2020). The comparison was brought further by suggesting that ENaC-𝛼 could have been the inspiration for introducing RRAR, a non-canonical furin cleavage site (Harrison and Sachs, 2022). Besides the amino-acid match, the suggestion was made because a lab group at the University of North Carolina studied ENaC-𝛼 (albeit the mouse version mostly), and the same university is home to another lab group that had collaborated with WIV. Finally some note that there are eight amino acids in common between ENaC-𝛼 and SARS-CoV-2.

There is no a priori rationale for choosing such a polybasic site rather than another one, and the match is essentially post hoc. In addition, in spite of a match at the amino-acid level, nucleotide sequences of ENaC-𝛼 and SARS-CoV-2 vastly differ (see Figure 6A; Garry, 2022). Five of the eight amino acids in common are also in related coronaviruses, the remaining three being in the insertion (see Figure 6). The match is therefore consistent with natural evolution. Finally, the comparison fails to explain the presence of a leading proline in SARS-CoV-2.

Proposed sources for the insert have different nucleotide sequences. (A) Source proposed by Harrison and Sachs (2022). (B) Source proposed by Lisewski (2024). (See Methods section for accessions.)

3.4.4. MERS-CoV MA 30

Another suggestion was made that SARS-CoV-2’s insert had been chosen to match the amino-acid sequence of a lab adapted MERS-CoV, MA 30, in which a point mutation changed PRSVR into PRRVR (Lisewski, 2024, Figure 6B). The match with SARS-CoV-2 was still imperfect and no proper explanation was provided to explain why a valine (V) would have been changed into an alanine (A) in SARS-CoV-2. In addition, while the experiment leading to MA 30 was published in 2017 (K. Li et al., 2017), the sequence was only submitted and published on Genbank in June 2020 (MT576585; Gutiérrez-Álvarez et al., 2021). Using the 2017 experiment as inspiration would have required intimate knowledge of the paper. In that theory, in a classical example of guilt by association, such knowledge was speculated to be due to the fact that the lead author (K. Li et al., 2017), of Chinese origin, had done his PhD at WIV between 2005 and 2010 (Morin, 2025); it was however omitted that his thesis was not on coronaviruses, and carried out in another group within WIV, a large research institute—i.e., not in the group working on SARS-like coronaviruses. In addition, the serine (S) to arginine (R) mutation in the furin cleavage site was not the only change in MA 30 compared to its MERS-CoV precursor. The original (K. Li et al., 2017) and subsequent (Gutiérrez-Álvarez et al., 2021) experiments did not disentangle the effect of the various other mutations that had appearing in the process of passaging MERS-CoV in mice, and therefore could not ascribe causality for the observed phenotypical changes specifically to the serine (S) to arginine (R) mutation. Finally, the nucleotide sequences in MA 30 and SARS-CoV-2 are different (see Figure 6B), and no explanation was provided for this difference.

These examples listed above are post-hoc attempts to rationalize the presence of a furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2’s spike. While none provides a compelling rationale accounting for the furin cleavage site’s peculiarities, some go further by making explicit allegations against specific researchers, despite the absence of any supporting evidence. Rather than being the sign of the intervention of an intelligent designer, the peculiarities of SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site are representative of natural “evolutionary tinkering”.

3.5. SARS-CoV-2’s evolution informs on the potential sources of the insert

Confusion about the potential origin of the insert creating a furin cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 also stems from an incorrect description of how insertions happen in coronaviruses, which are sometimes (incorrectly) seen exclusively as similar to homologous recombination (Wade, 2023). Insertions in coronaviruses can happen to due template switching (Garushyants et al., 2021), with RNA picked up from various sources, including the virus’s own RNA, RNA from another virus infecting the same cell, but also even host RNA (Y. Yang, Dufault-Thompson, et al., 2022).

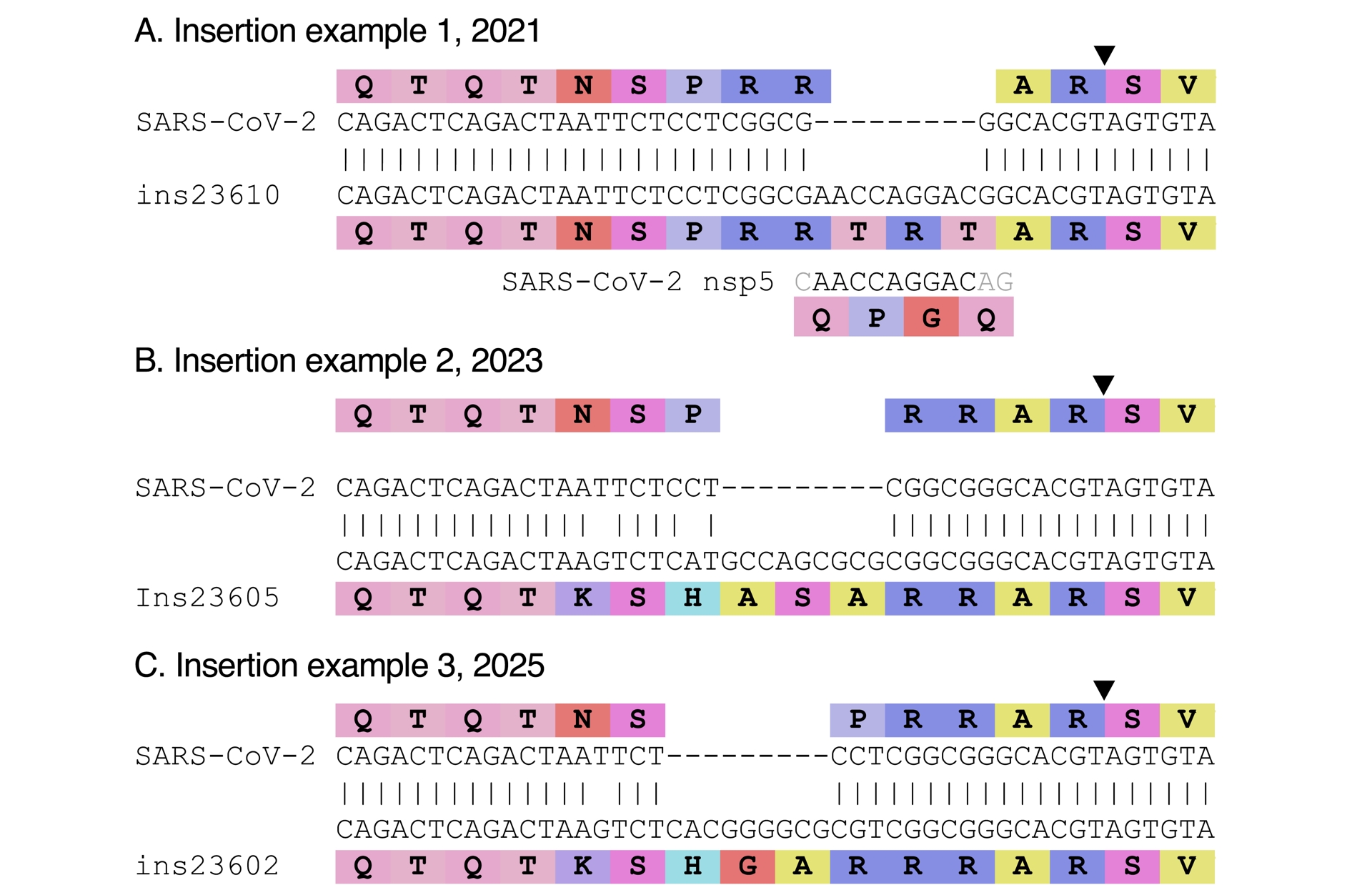

Insertions have happened repeatedly during the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in humans, including in its spike. Prominent examples include the EPE insertion (spike position 214) in the Omicron BA.1 variant that swept through the world from late 2021, and the MPLF insertion (spike position 216) in the lineage descending from Omicron BA.2.86, that started spreading mid-2023 and is still dominant at the time of writing.

In several instances during SARS-CoV-2’s evolution, observed insertions could be traced to the host (P. Peacock et al., 2021; Y. Yang, Dufault-Thompson, et al., 2022). While in many cases the source is putative (and the inserts too short to be certain), inserts were also found in controlled contexts, like in cell culture, with the insertion of sequences from the green monkey host cells (Y. Yang, Dufault-Thompson, et al., 2022). In avian influenza virus, the origin of some furin cleavage sites (that turn low pathogenic strains into high pathogenic ones) was traced to their host (Gultyaev et al., 2021). Transcripts similar to the SARS-CoV-2 insert can be found in mammal hosts (Romeu, 2023). While the exact source of the insert is unknown and cannot be determined with certainty because of its short length, a host origin is therefore within the realm of likely possibilities.

Finally, during SARS-CoV-2’s evolution, there were several occurrences of insertions near or in the furin cleavage site, mimicking the insertion that may have led to it. These insertions could be with high GC content, or also out of frame. Examples of such insertions are shown in Figure 7. Their existence demonstrates that such insertions can occur naturally, and that there is therefore nothing suspicious per se in the presence of an insertion at that location. That so many different scenarios are proposed for the source of the furin cleavage site sequence, none of them actually convincing, illustrates that SARS-CoV-2’s furin cleavage site is not a “smoking gun” (Lubinski and Whittaker, 2023).

Examples of insertions in SARS-CoV-2 near the cleavage site (represented by a black triangle). (A) Out of frame insertion detected in six genomes collected mid-2021, from Costa Rica (2), Canada (3) and the US (Florida; 1). A fragment similar to the insert is present in SARS-CoV-2’s genome (nsp5), in a different reading frame; it is shown below the alignment. (B) Insertion detected in 31 genomes from Austria (3), Sweden (1) and Germany (27), collected in 2023. (C) Insertion detected in two genomes collected in Spain and France in early 2025. This insertion was first spotted and shared by Ryan Hisner. Accessions are provided in the Methods section.

4. Conclusion

All data available to date point to a zoonotic, natural origin of SARS-CoV-2, linked to wildlife trade at the Huanan market. Early Covid-19 cases in Wuhan were found predominantly around the Huanan market, even for cases that had no reported epidemiological link to the market; the early diversity of SARS-CoV-2 is represented inside of the market; the market was one of the only few places in Wuhan selling wildlife; genetic traces of wildlife and of SARS-CoV-2 were found in the same stall inside of the market; limited viral diversity indicated a recent outbreak, consistent with the timings of cases that were found retrospectively. The absence of detection of infected animals is primary due to the absence of samples from the key animal species sold in the market. While the whole market was closed down in the early hours of January 1, 2020 (D. L. Yang, 2024), game stalls were reportedly already closed on December 31, 2019 (Red Star News, 2019), and disinfection was already in progress (Page and Khan, 2020). It is possible to invoke scenarios that make sense of these data and yet implicate a laboratory, for instance if infected animals were brought from a lab to the market to cover traces, but such a scenario is less parsimonious, because it requires the additional presence of infected animals in a lab.

Scientific work may only be based on actual data, not speculation (Débarre and Hensel, 2025). Additional SARS-CoV-2 sequence data from the early months of the pandemic were made public in the last couple of years (Lv et al., 2024; Hensel and Débarre, 2025); they did not challenge previous conclusions (Pekar, Moshiri, et al., 2025), and even reinforced links to the Huanan market (Hensel and Débarre, 2025).

There is a notable precedent for a change in conclusions for the origin of an outbreak that followed a regime change, namely in the case of the source of the 1979 anthrax outbreak in Sverdlovsk in the USSR (Meselson et al., 1994). Local authorities proposed and promoted the idea that the outbreak was caused by a natural source of tainted meat. The end of the USRR, over a decade later, allowed for a better flow of information. It was shown that the outbreak had instead its source in a military microbiology facility (ibid.). There is however a key difference between the 1979 anthrax outbreak and Covid-19: the conclusions presented in this article differ from the official ones in China. While the Huanan market was initially considered as source (Tan et al., 2020), its role is now contested in publications from China (W. J. Liu, Lei, et al., 2023; The State Council Information Office of the Peoples Republic of China, 2025)—as is an origin linked to research activities.

Elucidating the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is important from a historical point of view. Whatever the origin, however, the next pandemic will not necessarily follow the same pattern. It is therefore crucial to give ourselves the best chances to mitigate the chances of evolution of pandemic pathogens, both by monitoring and controlling lab experiments of potential pandemic pathogens (which are not limited to viruses), and by reducing our interactions with potentially infected animals, in particular in dense urban centers (Jones et al., 2008).

5. Methods

The various alignments presented in the figures were done with the msa package in R (Bodenhofer et al., 2015). The sources of the sequences (on Genbank unless indicated otherwise) are: NC_045512.2 (SARS-CoV-2); MZ937000 (BANAL-20-52); MN996532.2 (RaTG13); GISAID::EPI_ISL_412977 (RmYN02); NC_004718.3 (SARS-CoV); OK017908 (CD35); NC_025217.1 (Zejiang2013); NC_009020.1 (HKU5); NC_019843.3 (MERS-CoV); KF963241.1 (OC43); NC_026011.1 (HKU24); KY370046 (JL2014); NC_003045.1 (Bovine CoV); NC_048217.1 (MHV); NC_006577.2 (HKU1); MT576585 (MA_30); NM_001159575.2 (ENaC-𝛼). The BNT and Moderna sequences were obtained from Jeong et al. (2021). Data sources for Figure 7: https://doi.org/10.55876/gis8.250226ym (A), https://doi.org/10.55876/gis8.250226eb (B), https://doi.org/10.55876/gis8.250227vy (C).

The online codon-optimization tools used in Figure 4A are available at the following URLs:

- Vector builder: https://en.vectorbuilder.com/tool/codon-optimization.html

- Genscript: https://www.genscript.com/gensmart-free-gene-codon-optimization.html

- IDT: https://www.idtdna.com/pages/tools/codon-optimization-tool

- Twist biosciences: https://www.twistbioscience.com/resources/digital-tools/codon-optimization-tool

The proportions of the different nucleotides present at positions 23606–23611 (CGGCGG in the reference genome), in all available sequences of SARS-CoV-2, was estimated using CoV-Spectrum (C. Chen et al., 2022).

The insertions presented in Figure 7 were identified using GISAID’s search function (Khare et al., 2021), and checked with Nextclade (Aksamentov et al., 2021). Amino acid colors follow the palette proposed by Nextclade at https://github.com/nextstrain/nextclade/blob/master/packages/nextclade-web/src/helpers/getAminoacidColor.ts, designed after amino acids chemical properties (e.g., basic in blue, acidic in red, hydrophobic or aliphatic in yellow, etc.).

Acknowledgments

We thank Alex Crits-Christoph for discussions. We are grateful to the variant tracker community, professional and citizen scientists, for sharing their findings on Twitter and then Bluesky. We are also grateful to all the researchers providing tools to the community to follow the evolution of SARS-CoV-2, including but not limited to Nextstrain (ibid.), Outbreak.info (Tsueng et al., 2023), CoV-Spectrum (C. Chen et al., 2022), Gensplore (Sanderson, 2025), UShER (Turakhia et al., 2021), CoVariants (Hodcroft, 2021). No specific funding was received for this work.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0