1 Introduction

All living organisms are cellular. The inside of each cell (essentially water) is separated from the outside (also essentially water) by a thin lipidic membrane formed by the self-assembly of amphiphilic molecules. We have postulated that the amphiphilic molecules of primitive membranes must have been very different (simpler to synthesise abiotically) from either the present eucaryotic or procaryotic ones, n-acylphospholipids, or from the Archæal ones, complex polyprenyl phospholipids. We have been led to propose that the simple polyprenyl phosphates would fulfil all the conditions to be ‘primitive’ 〚1〛. We have synthesised these phosphates, and have shown that they do form vesicles, provided that their polyprenyl chains contain at least a total of 15 carbon atoms 〚2〛.

Once vesicles are formed, a series of new properties automatically result:

- • lipophilic molecules can be selectively extracted into the membrane 〚3〛, which may lead to condensation by an effect of the concentration;

- • anisotropic lipophilic molecules must be oriented in the anisotropic membrane 〚4〛,

- • molecules large enough not to diffuse through the membrane can be incorporated inside the vesicle 〚5〛, etc.

The automatic emergence of these novel properties may have been important as providing a mechanism by which ‘primitive’ vesicles may have evolved into progressively more complex units, more and more akin to proto-cells. This is the only alternative we see to the hypothesis of an ‘intelligent’ origin of living systems (‘intelligent’ is the word used frequently now by neocreationists as a substitute for ‘divine’; it is more or less equivalent to ‘teleologic’; our position is that a sensible positivist attitude should not be to refuse it a priori, but must provide alternative explanations).

By the formation of a vesicle, the amphiphilic molecules that were initially all equivalent become differentiated: some are now forming the outside half of the double-layer, and are on a surface of positive curvature, a convex one. The others form the inside half, of negative curvature, a concave surface. The outside molecules are less compressed than the inner ones at the level of their polar head, and should have different properties. An important factor is of course the size of the vesicles: the difference in curvature between the outside and inside monolayers is significant only for small vesicles (SUVs).

Several types of biological membranes, composed of mixtures of phospholipids, have indeed been shown to exhibit an asymmetric distribution of the phospholipids between the outer and inner leaflets 〚6〛, and this is often assumed to be characteristic of the complex biological membranes, containing not one kind of phospholipids, but several, and proteins of diverse kinds. In fact, however, it is an intrinsic property of small sonicated phospholipidic vesicles, even when they are devoid of proteins. The criterion that has usually been used for demonstrating this asymmetry is 31P–NMR, which is sensitive to the local environment and in particular to the local pH. For instance, Swairjo et al. 〚7〛 studied by 31P–NMR SUVs composed of a 1:1 mixture of of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (POPA, 1)/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC, 2), and observed two peaks for the POPA molecules, assumed to originate from those in the outer and in the inner leaflets because they were of unequal intensity. They interpreted this splitting by a difference in the apparent pKa’s of the phosphate head-groups of the POPA: the pKa2 of the inner leaflet POPA would be shifted to a value larger than 12, due the tighter packing of its head-groups on the concave surface: the closer the ionisable groups, the more difficult it must be to ionise them (cf. the classical Westheimer treatment of the pKa of diacids 〚8〛).

Hauser et al. 〚9〛 studied the effect of a pH-jump (pH >10) on unsonicated aqueous dispersions of sodium 1,2-dilauroyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (DLPA): this, in small unilamellar vesicles (20–60 nm), induces splitting of the 31P–NMR isotropic signal of the head-groups, which they considered again as indicative of a pKa gradient.

Similar splitting has been observed with SUVs made of egg lecithin, of a mixture of egg lecithin and egg phosphatidylethanolamine, of a mixture of egg lecithin and egg phosphatidylserine, of a mixture of 1,2-palmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and sphingomyelin, of a mixture of 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine and 1,2-dimyristoylamido-1,2-deoxyphosphatidylcholine, etc 〚10–12〛. Although these are all vesicles of phosphatidylcholines (lecithins), the choline group is not necessary for splitting the signal in 31P–NMR, as was shown in Hauser’s experiments with DLPA, mentioned above 〚9〛, and in our own experiments with (POPA), mentioned below. It had been suggested that the ester groups on the fatty acid chains are responsible for splitting, supposing that they could complex the phosphate group to affect the chemical shift in packing the head-groups. To test this hypothesis, we studied alkyl (not acyl) phosphatidylcholines. The 31P–NMR of SUVs (30 nm), composed of 1,2-di-O-dodecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine 3 at pH 7.35 did provide two signals of unequal intensity, interpreted as due to the inner (for the less intense one) and outer (for the more intense one) leaflets. Thus the ester groups are not responsible for the difference between the inner and outer phosphates.

We have tested whether it would be possible to demonstrate similar splitting in the case of our postulated ‘primitive’ membrane lipids, polyprenyl phosphates, and to interpret them in terms of vectorial properties on their ionisation.

2 Experimental

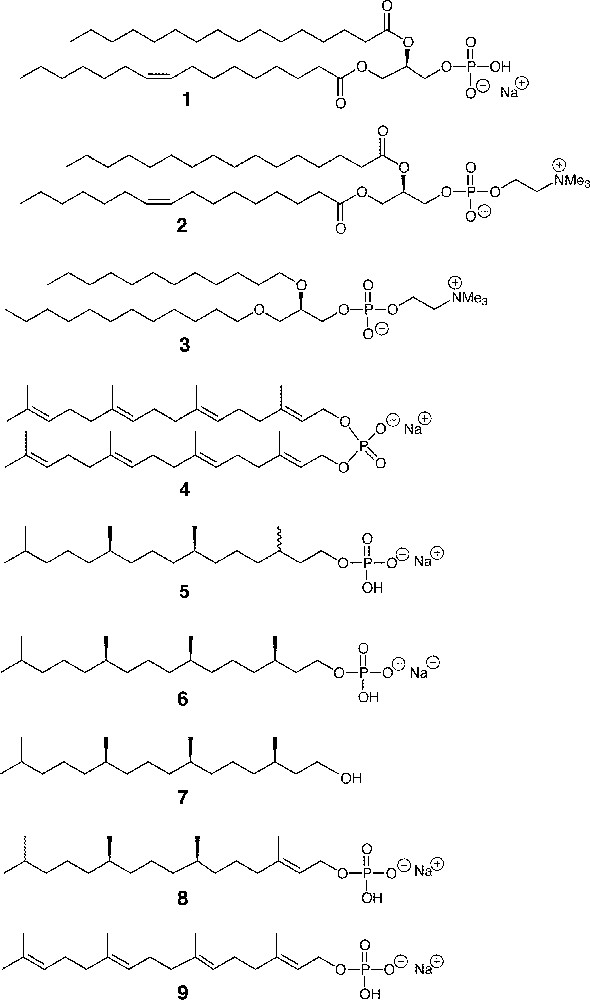

2.1 Materials (see the structures in Fig. 1)

Sodium 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (POPA, 1), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC, 2), and 1, 2-O-didodecyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine 3 were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Sodium di-geranylgeranyl phosphate 4, sodium 3R, 7R, 11RS-phytanyl phosphate 5, and sodium 3R, 7R, 11R-phytanyl phosphate 6 were synthesised according to the procedures described in previous papers 〚2, 13〛. 3R, 7R, 11 R-phytanol 7 was a gift of Prof. Tadashi Eguchi, Tokyo Institute of Technology.

Structure of phosphate lipids and other compounds studied.

2.2 Preparation of vesicles

Lipid mixtures were prepared from 1:1 chloroform/methanol solutions containing the appropriate lipid(s). The organic solvents were flushed out with a flow of argon, and the samples were further dried under reduced pressure. A typical small unilamellar vesicle (SUV) preparation was obtained using a 0.01 M suspension of lipid in pH 7.35 or pH 8.9 HEPES buffer (potassium-based, 0.1 M). The buffers contained 50 mM HEPES and 100 mM KCl. The pH was adjusted using a 0.01 M KOH aqueous solution. The lipid solution was sonicated using a Bioblock Vibracell 600 W probe-type sonicator for 9 min with 1 s pulses and 0.5 s delay, in an ice bath to avoid heating of the solution. The lipid solutions were briefly centrifuged and filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to remove metal particles from the probe tip. The size distribution and stability of the vesicles was then evaluated using a Coulter particle sizer. Large unilamellar vesicles (LUVs) of the same concentration and buffer were prepared by low-pressure extrusion using a Liposofas® extruder.

2.3 31P–NMR experiments

1H-decoupled 31P–NMR (121.5 MHz) spectra were measured on a Bruker 200 spectrometer. For locking purposes, to the vesicle solutions was added a drop of D2O. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (about 21 °C). Spectral deconvolution was accomplished using the WINNMR program. Chemical shifts were measured from 85% H3PO4 as an external standard.

3 Results and discussion

The technique used to characterise a difference between the outside and the inside monolayers of the membrane was 31P–NMR, as in the studies mentioned above. We studied systematically the structural characteristics of the phosphate lipids that might cause the difference in signals of 31P–NMR between phosphates in the inner and outer leaflets.

We first demonstrated that signals were, as expected, doublets for small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs, 25–35 nm in diameter), composed of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphate (POPA, 1), but not for large unilamellar POPA vesicles (LUVs, > 100 nm in diameter). As was mentioned above, the difference of available surface between the outside and the inside monolayers is of course only important for small vesicles, and the fact that it leads to two 31P–NMR signals may be due to the fact that the equilibrium constants in multi-dissociation systems is influenced by the distance between acid groups, like in dicarboxylic acids 〚8〛. The outside phosphate groups, less crowded, would be more acidic than the inside ones. Of course, this simple explanation might have to be replaced by more complex ones, in particular to take into account the fact that the inner surface is less accessible to water molecules.

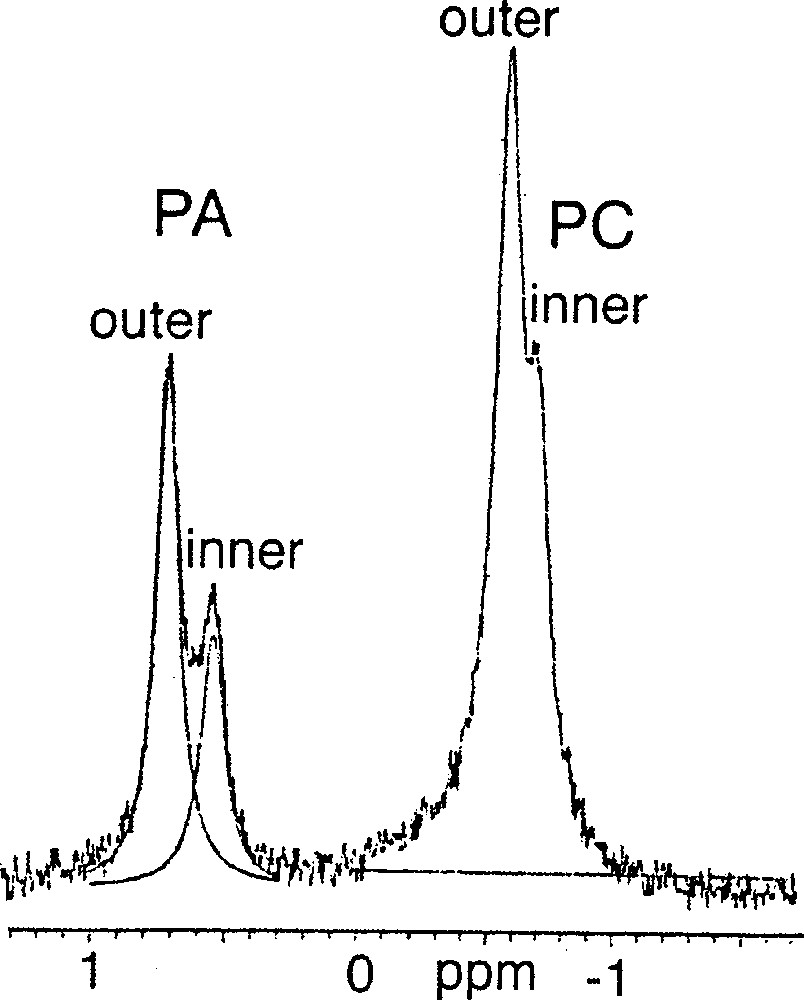

Among the polyprenyl phosphates, di-geranylgeranyl phosphate 4 would not produce SUVs at pH 7.35, but yielded LUVs of about 107 nm in diameter, in which the 31P–NMR did not show any splitting assignable to the two leaflets. Interestingly, at the same pH 7.37, a mixture (1:1) of POPC 2 and 3R, 7R, 11RS-phytanyl phosphate 5 formed SUVs, which showed two 31P–NMR doublets, one doublet for the phosphate group (0.63 ppm), the other one for the PC head-group (–0.68 ppm). The ratio of the intensities of the two peaks (2:1) is the same for both doublets and is compatible with their originating from the inner and outer leaflets (Fig. 2). Assuming Lorentzian line shapes, WINNMR deconvolution suggests a 2:1 ratio between the outer and inner numbers of the individual lipids, both for POPC and for phytanyl phosphate.

31P–NMR spectrum of a 1:1 mixture of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) 2 / 3R, 7R, 11RS-phytanyl phosphate 5 at 21 °C.

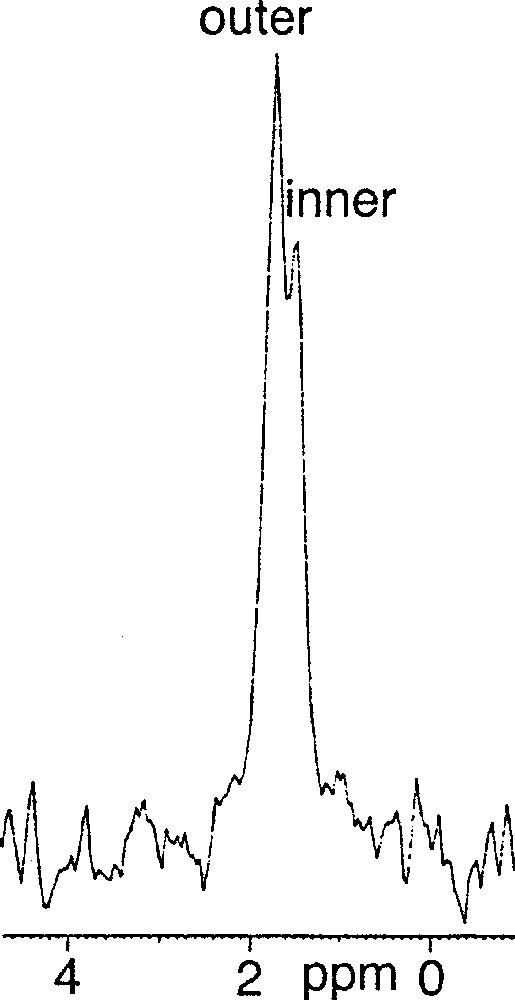

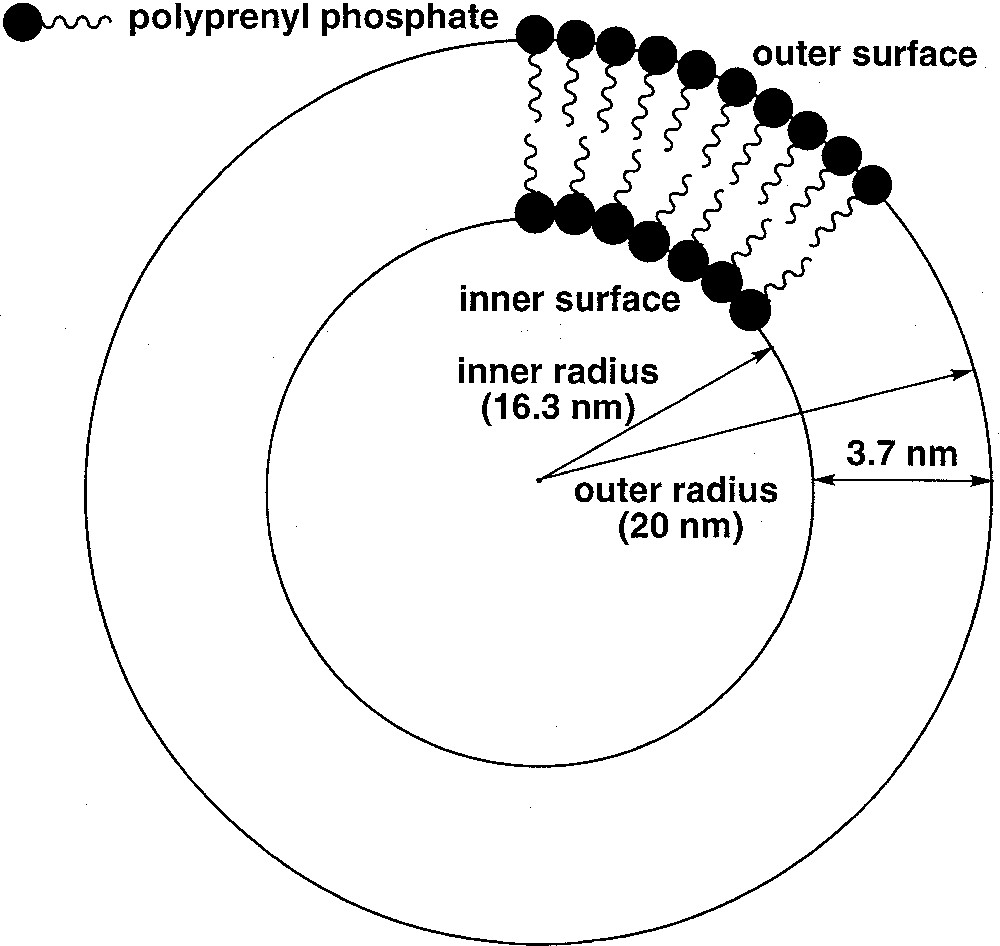

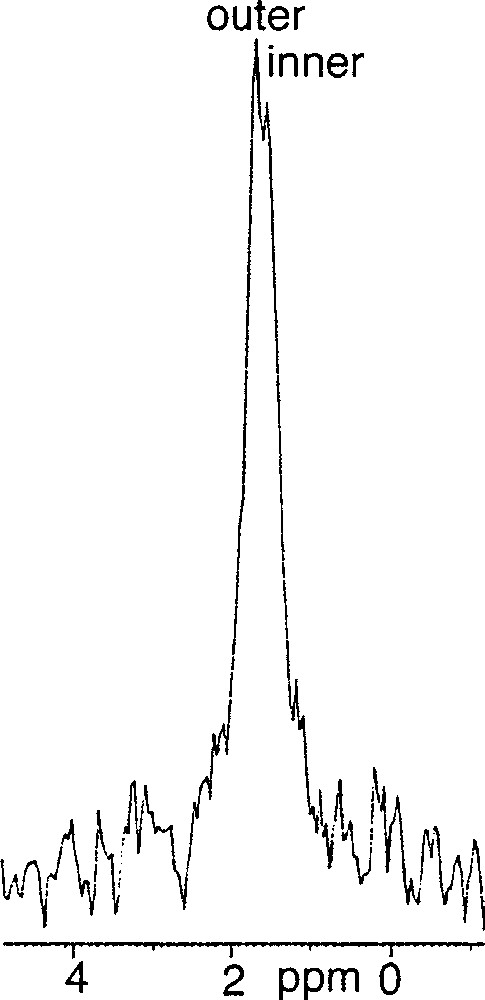

(3R, 7R, 11RS)-phytanyl phosphate 5 itself could not form stable SUVs at pH 7.35. Particle sizing showed that the vesicles initially formed, of about 35 nm in diameter, grew over a matter of hours. The resulting (3R, 7R, 11RS)-phytanyl phosphate LUVs (about 120 nm) showed, as expected, a single symmetrical peak for the 31P phosphate signal. We found however that a mixture of (3R, 7R, 11R)-phytanyl phosphate 6 and 5 mol% (3R, 7R, 11R)-phytanol 7 produced at pH 7.35 upon sonication stable SUVs (about 40 nm in diameter), in which 31P–NMR revealed a single symmetrical peak – we have observed in other cases that the addition of free polyprenols to the polyprenyl phosphate does facilitate the formation of vesicles. However, preparation of SUVs of this system at pH 8.9 was possible and led to two phosphate peaks at 1.75 and 1.50 ppm, with an intensity ratio of the downfield to upfield resonance of about 1.7 (Fig. 3). Following the literature 〚7, 9〛, we attributed the downfield signal to the phosphates of the outer leaflet of bilayer and the upfield signal to the phosphates of the inner leaflet. This assignment is reasonable on geometrical grounds 〚14, 15〛 (Fig. 4): the surface areas S for the outer and inner ‘spheres’ (calculated from S = 4 π r2 with, for the outer radius, r = 20 nm, for the inner radius r = 16.3 nm, and therefore for the bilayer thickness = 3.7 nm) are in the ratio of ca 1.5. Finally, the 31P–NMR spectrum of SUVs (about 60 nm), formed at pH 8.9 from pure (3R, 7R, 11R)-phytanyl phosphate itself, showed two signals for the phosphate (Fig. 5). Assuming Lorentzian line shapes, WINNMR deconvolution of the spectra in Fig. 5 gives a 1.5 intensity ratio between the outer (1.68 ppm) and inner (1.52 ppm) peaks, which matches quite well with a rough calculation value of 1.3:1 for the ratio of the outer and inner leaflet surface areas deduced from the average radius.

31P–NMR spectrum of 3R, 7R, 11R-phytanyl phosphate 6 / 5 mol% 3R, 7R, 11R-phytanol 7 at pH 8.9.

Schematic representation of the geometry of a small unilamellar vesicle composed of a polyprenyl phosphate, showing the curvature effect on the difference of packing between the outer and inner leaflets.

31P–NMR spectrum of 3R, 7R, 11R-phytanyl phosphate 6 at pH 8.9 at 21 °C.

For phytanyl phosphate (10–3 M), pKa1 is 2.9 and pKa2 is 7.8 〚2〛. At pH 8.9, the dianion of the phosphate head-group is predominant, and occupies probably mostly the outer leaflet. This packing asymmetry could contribute to preserve small-sized vesicles and to be translated into a difference in the ionisation state of phosphates on both sides, a monoanionic form being more favourable on the inside than a dianionic form. On the other hand, at pH 7.35, where a mixture about 1:1 of monoanion and dianion exists, the outer and the inner phosphate 31P–NMR signals are no longer different, which may indicate a fast exchange by prototropy.

4 Conclusion

Phospholipid asymmetry in biological membranes is general, and is characterised by a different lipid composition between the outer and inner leaflets of the membrane bilayer. The transmembrane asymmetry is usually assumed to be controlled by different membrane proteins, but we have now demonstrated that an asymmetric distribution can be produced even from a single membrane-forming component, phytanyl phosphate, provided that SUV’s were formed at a relatively high pH. The outside phosphate groups would be more easily dissociated than the inside ones. The resulting gradient of electrochemical properties would lead necessarily to an asymmetric orientation of any additional dipolar constituent inserted into the membrane, especially for acid/base sensitive ones such as membrane peptides. The asymmetric insertion into the membrane of such a molecule (antiparallel to the first ones as regards their dipolar properties) would enhance the difference of composition between the outer and inner layers. It is also quite conceivable that this asymmetry may be inherited when the vesicle, initially small, grows to become cell-sized. One of the referees has quite pointedly noted that small vesicles can be obtained only through sonication; we have for the time being to assume that natural phenomena like thunderbolts or volcanic rumblings, or maybe even only wave breakings, can lead to the same effects as sonication.

The growth of small asymmetric vesicles may therefore be a mechanism leading to the ‘self-complexification’ of the self-assembled system of phospholipids, a factor that may well be of extreme importance for the initial steps towards the formation of ‘protocells’.