1 Introduction

Cell membranes that protect the cell and at the same time allow for the transport of biologically important small molecules across the cell boundary are lipid bilayers that contain a hydrophobic interior flanked by hydrophilic surfaces. The partitioning of hydrophilic solutes into these bilayers is an important process intimately involved in events such as drug uptake and metabolite transport and may be important in the mechanism of anesthetic drug action.

A great number of biomolecules and drugs are water-soluble species, often insoluble in lipid membranes. As a result, their transport across membranes must be facilitated by specific carriers. A great number of naturally occurring carriers are known for amino acids, neurotransmitters, nucleosides, sugars etc. Usually these are proteins mostly of unknown structures. Synthetic carriers for the facilitated transport of hydrophilic biomolecules and drugs across cell membranes are rare and the design and synthesis of such molecules are important, and of vital concern to biology and pharmacology.

The transport of amino acid derivatives or nucleotides by synthetic carriers across CH2Cl2 or CHCl3 bulk liquid membranes, BLMs, has received considerable attention and has been the subject of numerous reports. Among them are included: (a) the pH-gradient-driven transport of amino acids by positively or negatively charged hydrophobic carriers [1]; (b) the transport of hydrophobic amino acids from aqueous solution at the isoelectric point using Kemp’s triacid-acridine 2:1 condensate [2]; (c) the transport of phenylalanine in a neutral pH transport system facilitated by cooperative ditopic interactions between the amino acid, and non-bound arylboronic acid and crown ethers [3]; (d) the simultaneous transport of anions and cations by a neutral bifunctional receptor that contains calix[4]phosphate and an appended uranyl salophene unit [4]; (e) the ditopic fixation and transport of amino acids with a bifunctional metalloporphyrin receptor [5]; (f) the proposed ditopic transport of amino acids by lanthanide (III) tris(β-diketonate) complexes [6]; (g) the use of phenylboronic acid/trioctylmethylammonium bromide as a carrier of amino acids through a ClCH2CH2Cl BLM [7]; (h) the transport of amino acid derivatives by certain hydrophobic, neutral LM(Cl)2 complexes (M = Co2+, Cu2+, L = a macrocyclic polyamine ligand) in basic aqueous solutions. This transport is assisted by the concomitant transport of antiport halide ions [8–10]. The recognition of thymidine nucleotides by the zinc(II)-bis(cyclen) ditopic receptors also has been reported [11].

In the majority of these biological transport studies, the bulk liquid membranes, BLMs, are non-aqueous, hydrophobic solvents and, in transport experiments, they contain the carrier and also serve as barriers between the aqueous source and receiving phases.

The concentration gradient between the source compartment (containing the transportable guest) and the receiving compartment (initially pure water) is the thermodynamic driving force for transport. Transport occurs at various rates, subject to solubility properties of the host-guest complex and kinetic constrains. It is optimally effective when the ΔΔG of the dehydration/complexation steps (equation (1)) is such that the complex formation constant, K , is of a magnitude that will facilitate extraction of the guest from water but will also allow for its release:

| 1 |

Major drawbacks in most of the previous studies have been either slow rates of transport or carrier instability.

Our interest in supramolecules containing individual subunits with unique structural and reactivity properties has led us to the synthesis of a new class of crown-functionalized salicylaldimine ligands [12–15]. In this paper we report on the metal complexes of these multinucleating ligands and their use in the recognition and transport of zwitterions and amphiphilic molecules across hydrophobic barriers

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis of -tBu4-salphen-crown ether ligands and complexes

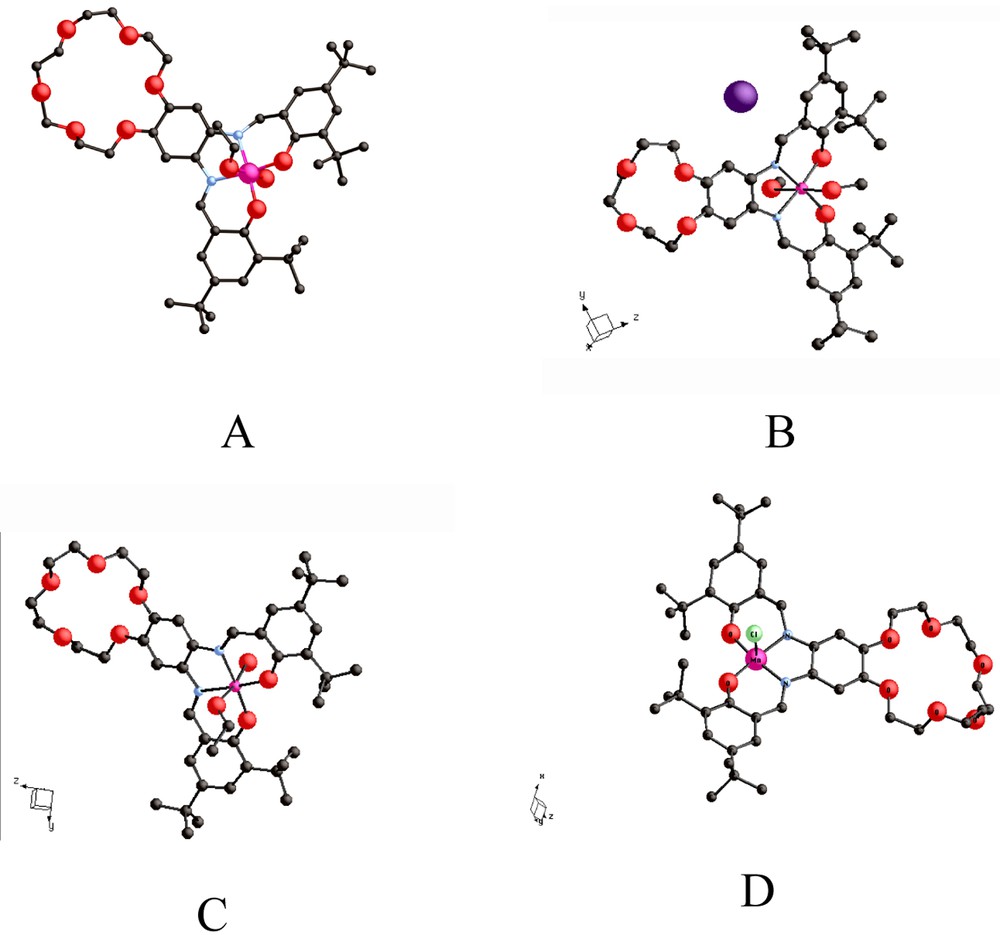

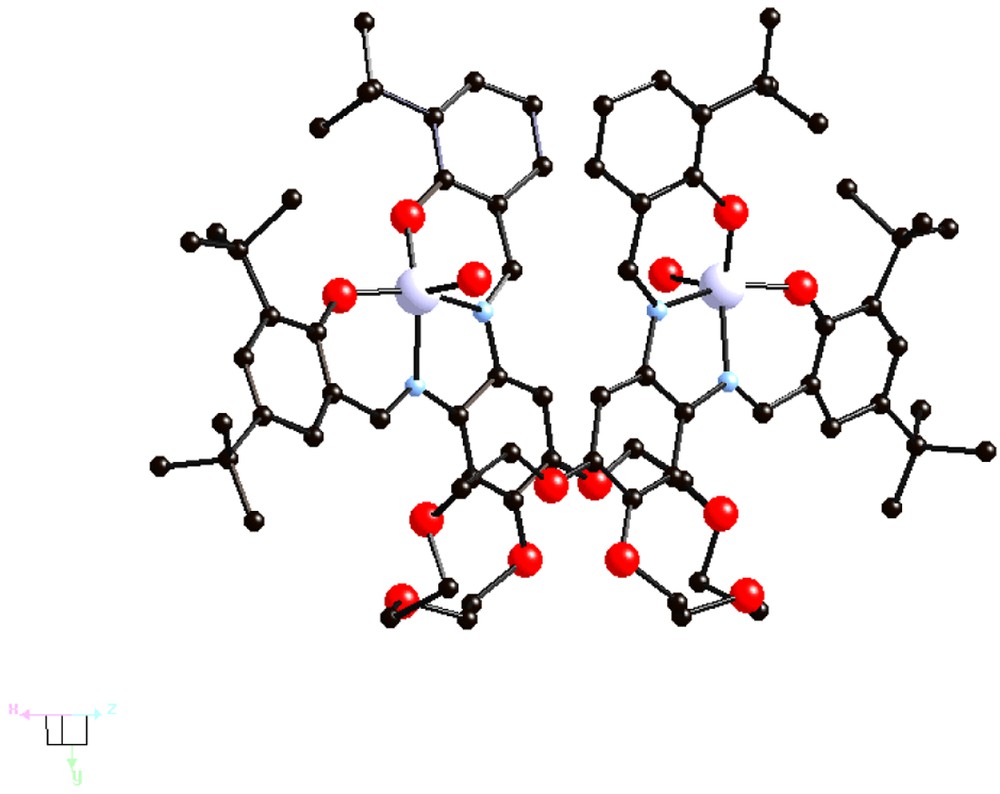

The general procedures employed in the synthesis of the {H2-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6} ligands and complexes have been reported [13–15] and also have been used in the synthesis of the 15-crown-5 and 12-crown-4 derivatives (Fig. 1) [16].

The structures of complexes: (A) {(EtOH)(H2O)Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-3 n-cr-n}+ I–, n = 6 [12–14]; (B) {(MeOH)2Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-3 n-cr-n}+ I–, n = 4 [16]; (C) {(MeOH)(H2O)Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-3 n-cr-n}+ I–, n = 5 [16]; (D) {(MeO)Fe3+-tBu4-salphen-3 n-cr-n}+ I–, n = 6.

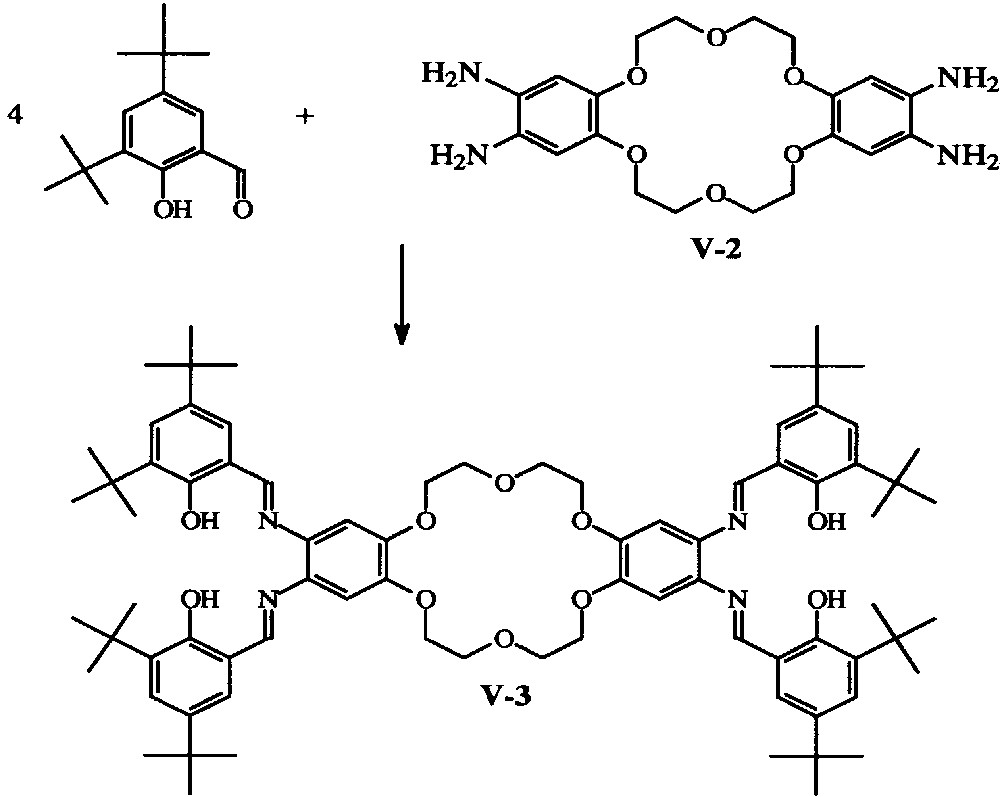

With dibenzo-crown ethers, 2:1 tBu4-salphen:crown ether molecules have been obtained (Fig. 2) with 18-crown-6, 24-crown-8 [13–15] and 30-crown-10 ‘bridges’ [16].

General synthesis of the {[H2-tBu4-salphen]2318-cr-6}hybrid ligands [12,13].

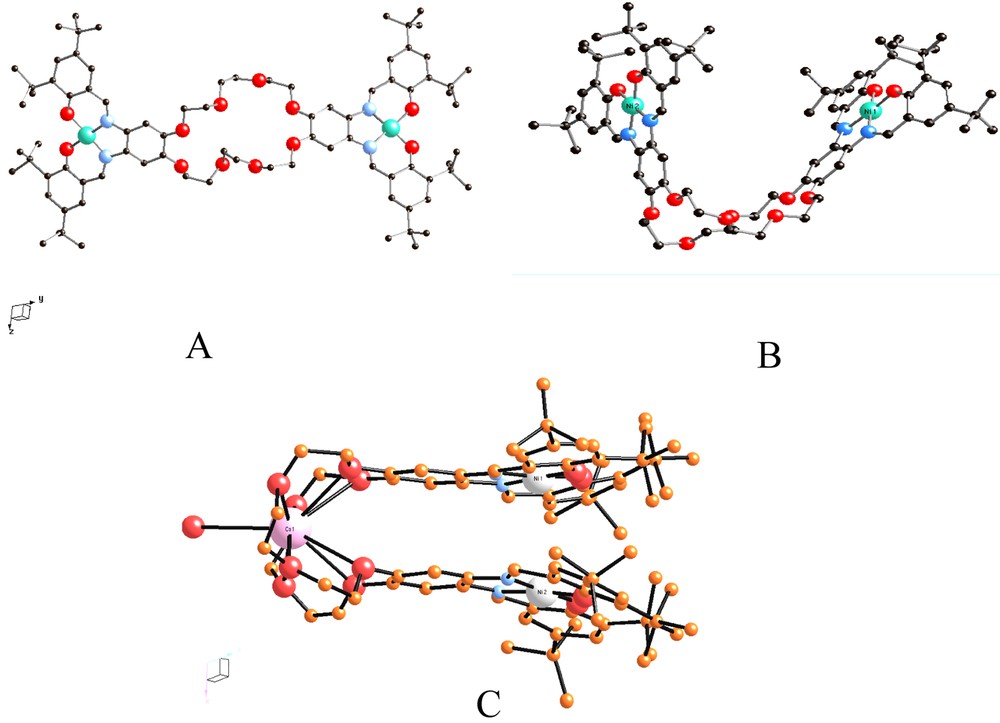

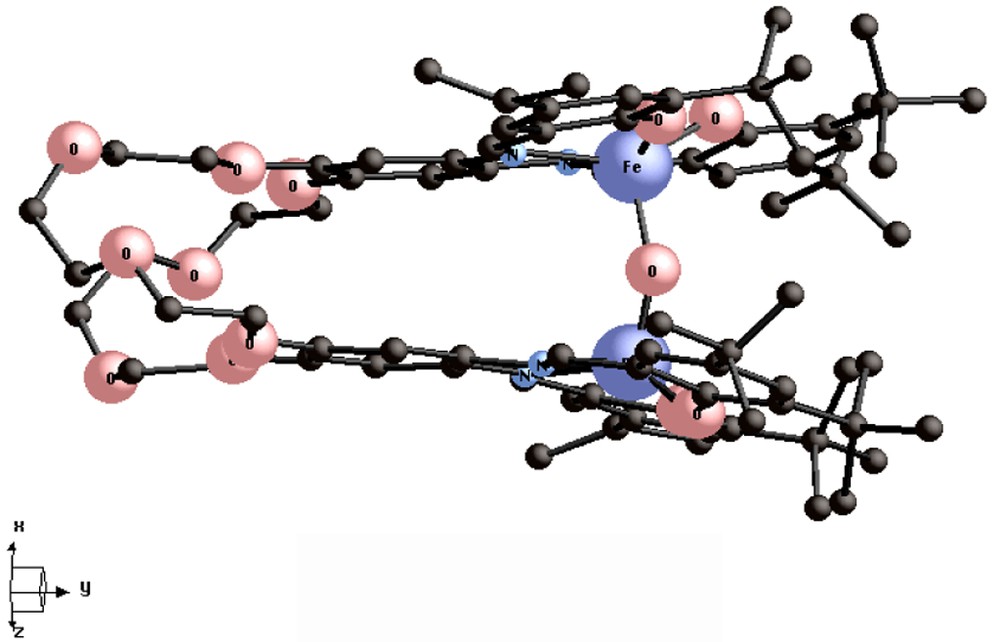

Various metal complexes have been synthesized with these ligands and the structures of the {[Ni2+-tBu4-salphen]2[24-cr-8] and {[Ni2+-tBu4-salphen]2[24-cr-8]Cs complexes demonstrate the structural flexibility of the 24-c rown-8 bridge (Fig. 3).

Two forms of the {[Ni2+-tBu4-salphen]2[24-cr-8] complex, IV, both found in the same asymmetric unit [13] (A, B), and the Cs adduct of the same complex (C). In the latter, the Cs+ ion is nine-coordinate bound to the 24-cr-8 ether and to a water molecule. The Ni–Ni distances in (A), (B), and (C) are 17.5, 11.6, and 4.1 Å, respectively.

The tertiary butyl groups in the salicylaldehyde subunits of the ligands serve two purposes: (1) they impart highly lipophilic character to one end of the ditopic molecule and (2) they preclude short intermolecular interactions of the coordinated oxygen atoms with Lewis acids. A variety of metal ions (Mn3+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Co2+ Ni2+, Cu2+) have been incorporated within the N2O2 cavity of the salphen subunits in the 18-crown-6 and 24-crown-8 hybrids [13]. The {Ni2+-tBu4-salphen-3 n -cr- n } complexes, I, are neutral molecules [12,13] and the {M3+-tBu4-salphen-3 n-cr-n} complexes (M = Mn, Fe, Co) are monocations.

The {(EtOH)(H2O)Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+Cl–, II, and {(MeO)Fe3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}, III, complexes (Fig. 1A and D) contain six-coordinate Mn3+ and five-coordinate Fe3+ ions, respectively, and are obtained in high yield by air oxidation of the corresponding divalent complexes. Both II and III are very soluble in non-polar organic solvents and totally insoluble in water. It is worth emphasizing that the Cl– counterion that accompanies II is not directly coordinated to the oxophilic Mn3+ ion, which instead is coordinated by a water molecule and an ethanol molecule. Similar coordination is observed with the 12-cr-4 and 15-cr-5 ether analogs (Fig. 1B and C). The {[Ni2+–tBu4-salphen]224-cr-8} complex, IV (Fig. 3A and B) contains a four-coordinate Ni2+ ion and shows both linear and ‘hairpin’ structures that demonstrate the flexibility of the 24-crown-8 unit. The bending that places the two Ni2+ ions within 11.6 Å from each other is further enhanced (Ni–Ni = 4.1 Å), when Cs+ is added to the 24-crown cavity).

The {[(Cl)Fe3+-tBu4-salphen]2-24-cr-8} complex V (Fig. 4) also has a ‘hairpin’-type structure, with a Fe-Fe separation of 6.05 Å. It undergoes hydrolysis under basic conditions to give the oxo bridged dimeric complex {[Fe3+-tBu4-salphen]2[μ-O][24-cr-8]} VI (Fig. 5).

Structure of the {(Cl)[Fe3+-tBu4-salphen]2[24-cr-8]}, V [13].

Structure of the {[Fe3+-tBu4-salphen]2[μ-O][24-cr-8]} dimer, VI [13].

2.2 Transport studies through bulk liquid membranes

2.2.1 Tryptophan, serotonin

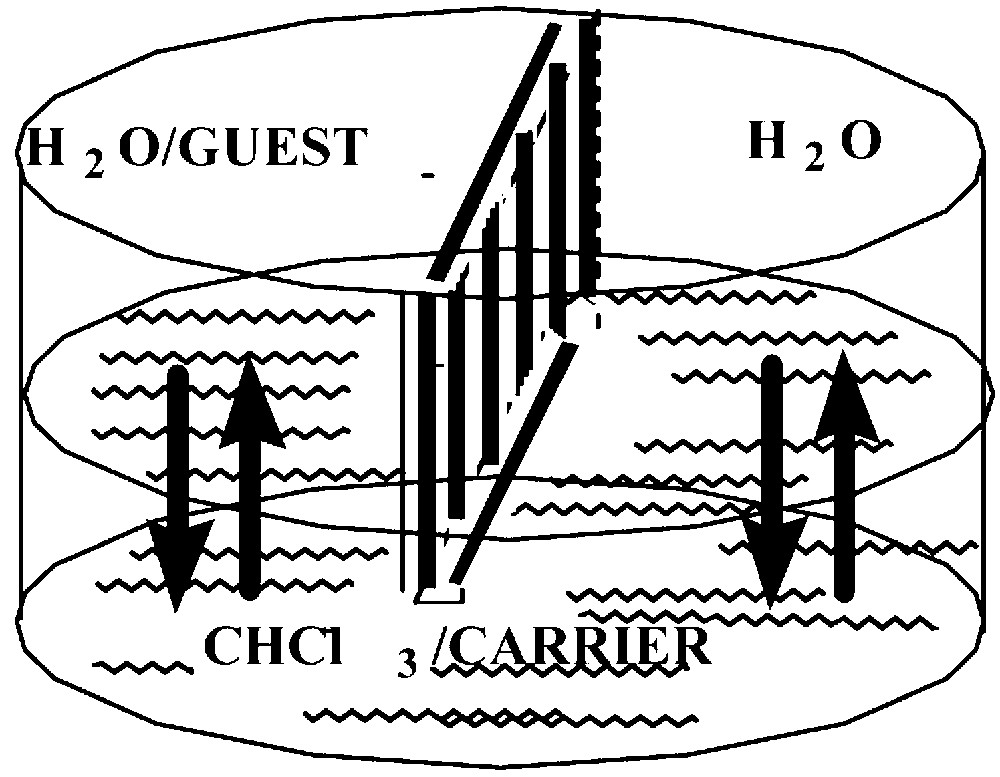

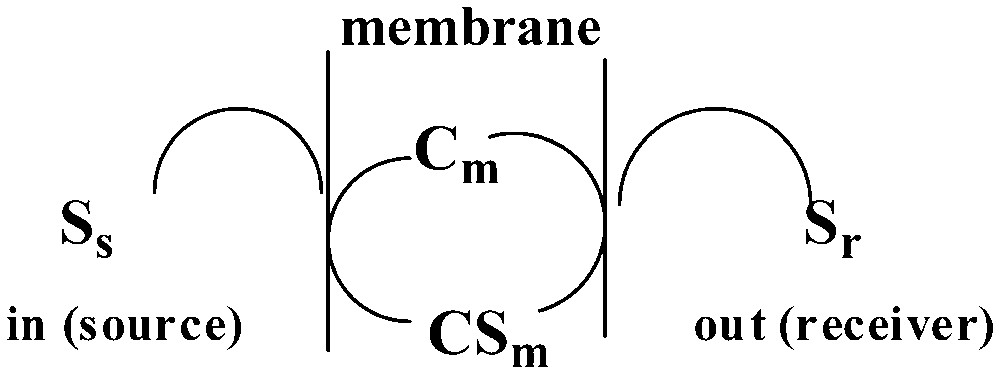

The facilitated transport of zwitterionic, lipophilic amino acids, dipeptides tripeptides, serotonin, dopamine and the nucleosides adenosine, guanosine, thymine, and cytosine was investigated across CHCl3 BLM and found effective to various extents with different {M-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6} complexes. In this paper, we report on our transport studies with tryptophan and serotonin. The cell shown in Fig. 6 was used.

The cell used in the transport studies across bulk liquid membranes, BLM [5].

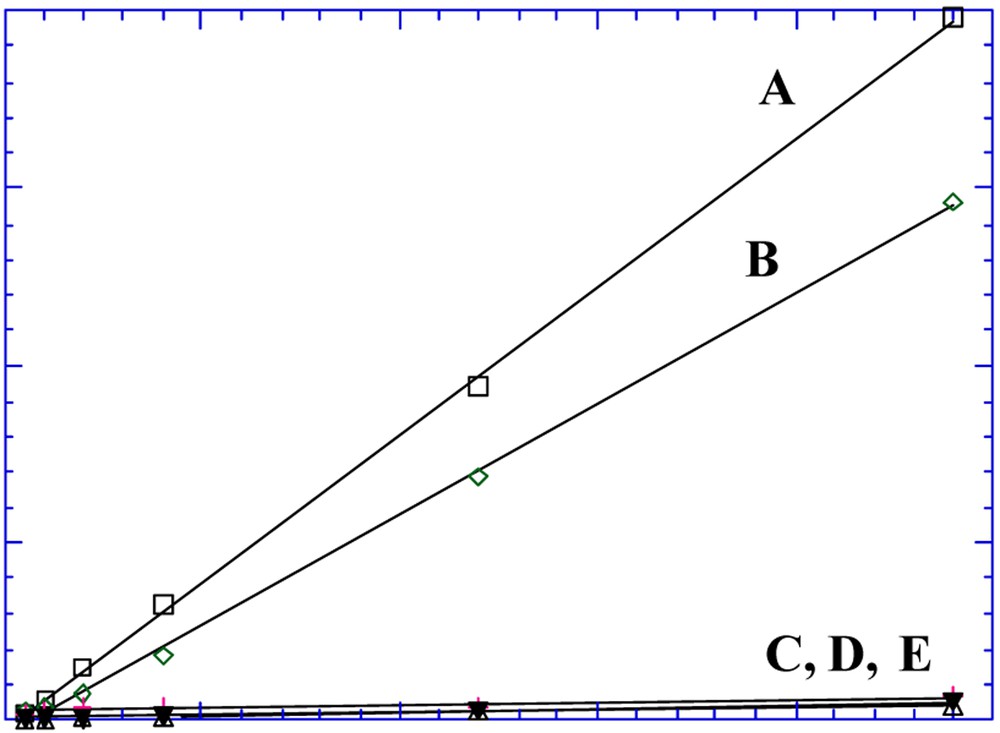

The Ni2+ complex, I, and its derivatives, the corresponding Cu2+ complex and the benzo-18-C-6 crown ether, that was investigated as a control, were equally ineffective in the transport of tryptophan [15]. In contrast, the Mn3+ complex, II, readily transported tryptophan (Fig. 7) by a process driven by the tryptophan concentration gradient [12,14]. The concentrations of tryptophan in the receiving and source compartments asymptotically reach equal values as the transport progresses. Nearly as effective in transport was the neutral {Fe3+-tBu4-salphen-3n-cr-n}2O, n = 6, complex (Fig. 8).

Transport of tryptophan by: (A) Mn-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+ I–; (B) {[Fe3+ -tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6]2[μ-O]; (C), (D) the {[M-tBu4-salphen]-[18-cr-6]} carriers M = Ni, Cu; (E) benzy18 cr-6 [12,14].

Structure of the {[Fe3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6]2[μ-O] complex [13].

We have attributed the poor transport performance of I and of the Cu2+ analog to the stability of the square planar Ni2+ and Cu2+ ions and their inability to bind axial ligands.

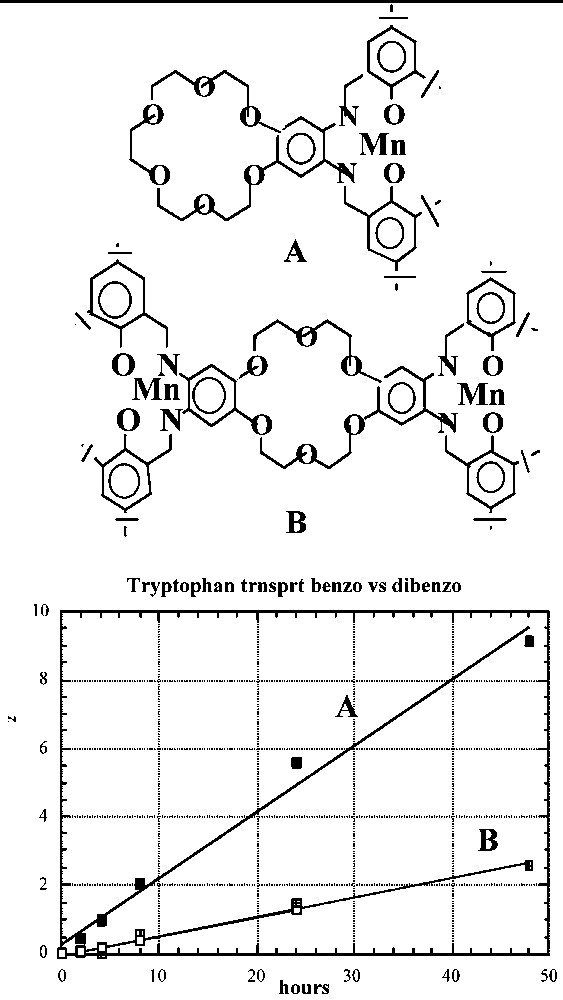

The importance of the unencumbered crown ether unit in II becomes apparent when the transport properties of II are compared to those of the {[Mn-tBu4-salphen]2-[18-cr-6]}2+·2 I– carrier with two Mn-tBu4-salphen units surrounding the 18-cr-6 unit (Fig. 9). The inferior performance of the latter may be due to the fact that in this carrier the hydrophilic part of the molecule is flanked by two very hydrophobic units and is not free to assist in retrieving the tryptophan molecule from the water solution. It is possible that the observed difference in transport rates is due to the presence of only two aliphatic ether oxygen donors in the {[Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-X}2{[18-cr-6] carrier and the consequent weaker interactions possible with the dibenzo-crown unit. This possibility can be tested using derivatives of II that also contain two aliphatic ether donors.

Transport of tryptophan by: (A) Mn-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+ I– and (B) {[Mn-tBu4-salphen]2-[18-cr-6]}·2 I– carriers across a CHCl3 BLM [12–14].

Various modes of interaction can be envisioned between the carrier and the zwitterionic form of tryptophan. They may involve such interactions as: (a) carboxylate coordination to the Mn3+ center, (b) H-bonding of the -NH3+ to the crown ether cavity of the carrier, (c) carboxylate coordination to an alkali metal bound in the crown ether cavity, and (d) H-bonding interactions between the indole NH proton and a hydrogen bond accepting site within the carrier. There is no apparent difference in the tryptophan transport rate when the 18-cr-6 unit in II is replaced by a 24-cr-8 unit.

The bathochromic shifts of the 470-nm band, caused by axial ligand coordination to the Mn(III) center, in derivatives of II with various counterions, indicate that this electronic absorption is very likely due to a M-ligand charge transfer, MLCT, process. The relative substrate transport rates decrease as the bathochromic shift of the MLCT band (at 470 nm in the BPh4– anion) increases. The differences in the bathochromic shift of the CT absorption reflect differences in the magnitude of Mn(III)-axial-ligand interactions. Generally, the transport data indicate [12] that the weakly coordinating anions give carriers that transport amino acids more effectively in the order: B(Ph)4– > I– = Piv– > Cl– > Ac–.

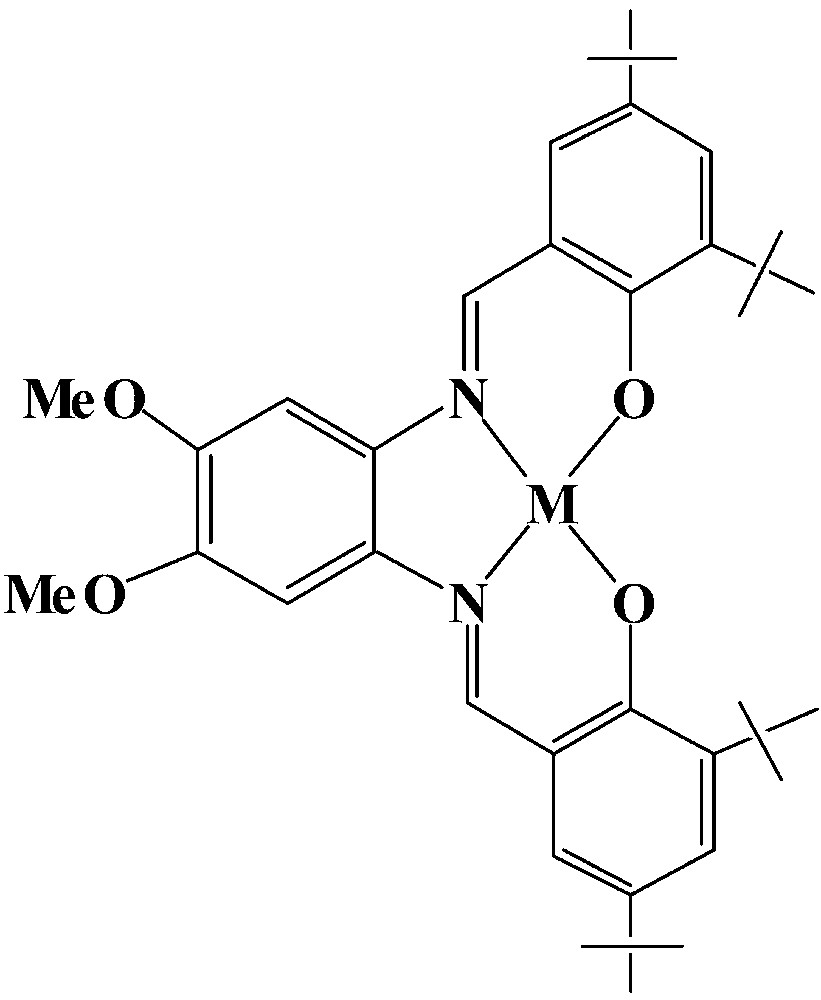

Transport studies were conducted to determine whether the ditopic receptors are more efficient transporters than an equimolar mixture of two similar monotopic half-receptors. The transport properties of a 1:1 mixture of the Mn-veratrol complex (Fig. 10) and benzo-18-crown-6 were compared to those of {Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+ X– or {Mn3+-tBu4-salphen veratrol}+ X–. The results show [1] that, in an equimolar mixture, the two carrier components function synergistically. The rate of transport observed with II however was still about 30% faster and indicates moderate ditopic cooperativity. The same experiments carried out with serotonin show greater ditopic cooperativity and can be attributed to a better dimensional matching between the donor–acceptor pairs within the serotonin-II complex. In II the acidic and basic sites are closely spaced such that that the simultaneous binding of the tryptophan zwitterion by both the carboxylate group (to the Mn3+) and the ammonium group (to the crown ether) is not possible unless the crown ether unit bends severely (to a right angle or more) towards the salphen unit. The ditopic cooperativity shown in the transport of substrates has been reported previously [17] for the crown-ether-functionalized boronic acids in the facilitated transport of catecholamines. The synergism displayed by the mixture of the two separate carrier components of II in the transport of tryptophan has been reported previously [17], for equimolar mixtures of arylboronic acids and crown ethers, in the transport of L-phenylalanine through CHCl3.

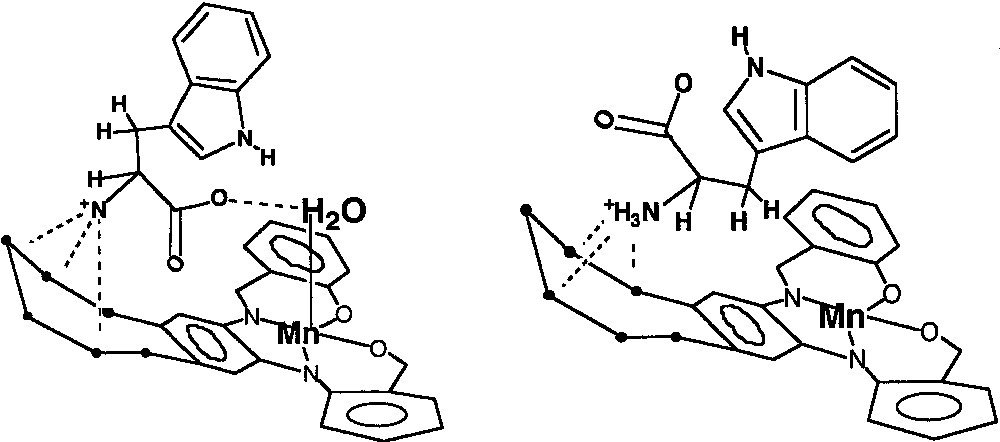

The M-tBu4-salphen veratrol complexes

Molecular mechanics calculations [12] on the tryptophan-II complex (Fig. 11) support this contention and show that when tryptophan is placed in the pocket of the carrier that contains a water molecule axially coordinated to the Mn(III) center, the relative energy of the guest-host complex decreases. In the energy minimized structure, in addition to RNH3+ hydrogen bonding with the crown ether appendix, short hydrogen bonds are found between the amino acid carboxylate group and the Mn(III)-bound water molecule (Fig. 11A). These hydrogen bonds (N–H···O, 2.69 Å; C···H–O–H, 2.51 Å) are to be contrasted with those found in the energy-minimized structure without the Mn(III)-bound water molecule (Fig. 11B). In the latter case, the only hydrogen bonding interaction is between the RNH3+ unit and the crown ether (N–H···O, 2.69Å; C–O···Mn, 3.79 Å).

Schematic illustrations of the energy-minimized structures of the tryptophan-{Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+ complexes: (A) the lower energy complex with Mn-coordinated water and (B) the higher energy complex without Mn-coordinated H2O [12].

The same type of calculation was carried out with serotonin. With a water molecule axially bound to the Mn(III) ion in II, the energy-minimized structure (Fig. 12A) shows the relative energy of the serotonin-II complex much higher than that of the complex without an axially bound water molecule (Fig. 12B). The lower energy of the latter is not unexpected considering the close distance matching of the two donor-acceptor pairs [12].

Schematic illustrations of the, energy-minimized structures of the serotonin-{Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+ complexes: (A) the higher energy complex with Mn-coordinated water and (B) the lower energy complex without Mn-coordinated H2O [12].

Thus far the transport data suggest that the initial carrier-amino acid contact is the rate-determining step and occurs between the crown ether unit of the carrier and the –NH3+ unit of the zwitterion. This suggestion also is supported by the observed inhibition of transport in the presence of the crown-blocking K+ ion. The slow transport rate by the benzo-18-crown-6 molecule shows that a crown ether interaction with the amino acid alone is not sufficient for effective transport, although it should be recognized that the crown ether is less hydrophobic than the tBu-salphen-crown ether receptor.

For the facilitated transport of a given solute through a membrane (Fig. 13), the flux [18], Jsolute, is defined as [19]:

Facilitated transport of a solute S through a membrane m by a membrane-residing carrier, Cm.

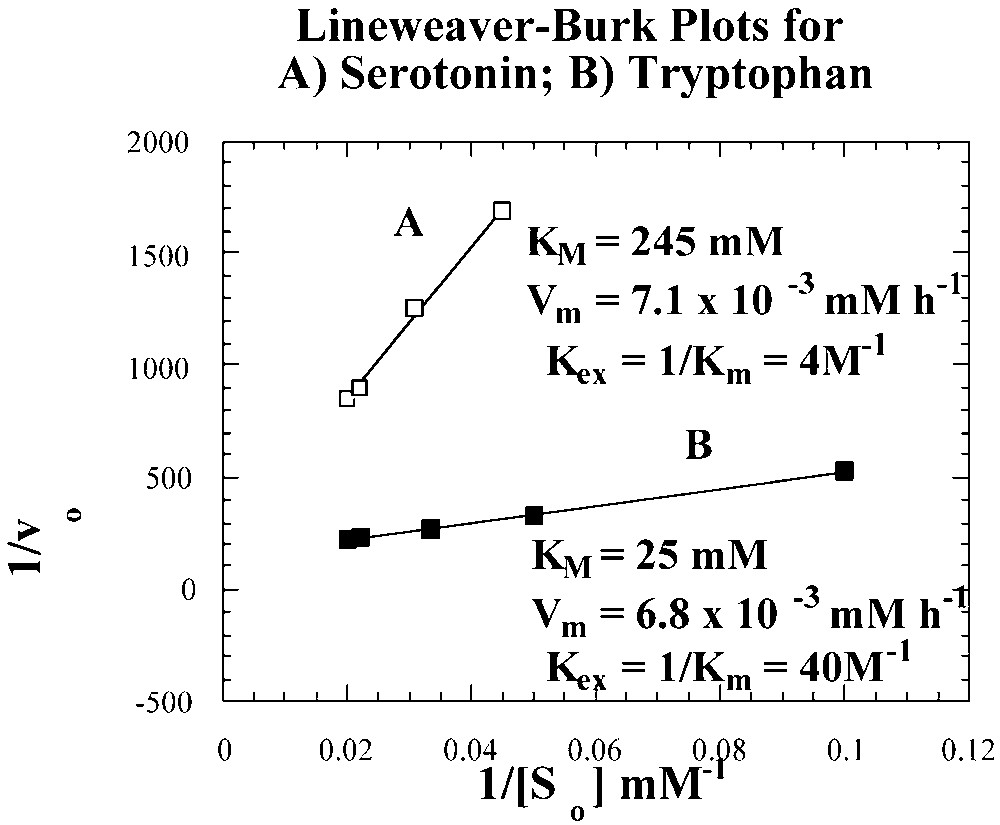

Michaelis–Menten kinetics for serotonin and tryptophan transport by II–I [12].

From the apparent Michaelis constants (Km) of 25 mM and 245 mM, carrier-permeant extraction constants (Kex = 1/ Km) of 40 M–1 and 4 M–1 were determined, respectively, for the tryptophan and serotonin carrier complexes. Theoretically, the transport of serotonin as the hydrochloride derivative should be more appropriately treated, as a symport-transport case [19]. The successful application of the same Michaelis–Menten kinetics treatment for serotonin HCl, as that used for tryptophan, however suggests that the HCl derivative of serotonin in CHCl3 behaves as a tight ion pair rather than as an electrolyte.

Rate studies as a function of temperature and Arrhenius plots were used to determine activation energies and activation parameters for the process of transport of tryptophan and serotonin [12].

The ΔEs of activation of 20 and 16 kcal mol–1 indicate diffusion-controlled processes [19] through the Nernst layer at the CHCl3–H2O interphase.

The transport of serotonin·HCl by II+–I– proceeds at a respectable rate, but which is still half of that of tryptophan. The transport of dopamine (in a buffered solution at pH 7.2) by the same carrier is slower, but still much better than the transport observed with the benzo-18-cr-6 carrier) [1]. The difference in transport rates between serotonin and dopamine is probably due to differences in hydrophobicity between these two molecules. The distance between the electron-pair donor hydroxyl groups and the hydrogen-bond donor amino groups in both are very similar, and for both, {Mn3+-tBu4-salphen-18-cr-6}+, II, can serve as a ditopic receptor. The flux [20] of the previously reported [19] transport of serotonin by the boronic-acid-functionalized crown-ethers is nearly 100 times smaller than that determined for II.

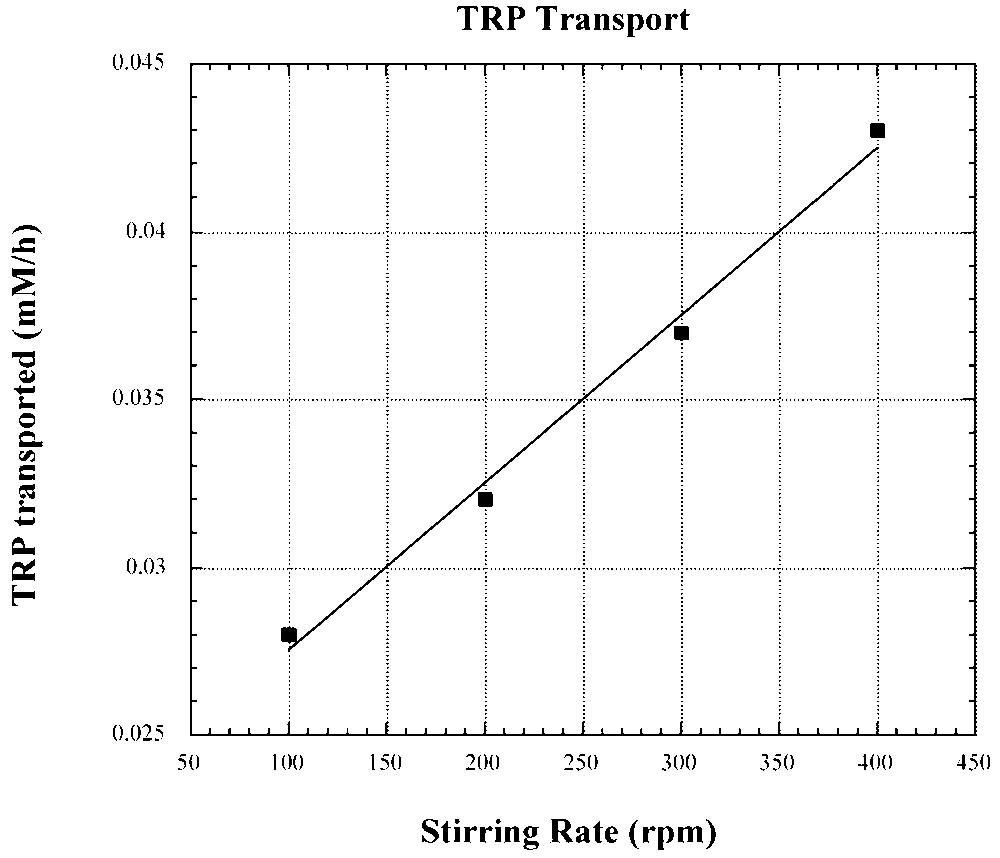

For the transport of tryptophan, through a CHCl3 BLM, the dependence of transport rate on the stirring rate of the BLM (Fig. 15) unequivocally indicates a diffusion-controlled process [20]. An increase in the stirring rate is expected to reduce the thickness of the Nernst layer. With a hindered carrier (Fig. 9B), difficulty in rapidly penetrating the interphase may introduce a slow kinetic step that may in fact become the rate-determining step.

Dependence of facilitated tryptophan transport through a CHCl3 BLM by II–I on the stirring of the BLM.

The lipophilicity of the amino acids is correlated to their solubility in water [2,3,21]. The transport rates of the three lipophilic amino acids, tryptophan, leucine and phenyl alanine (Table 1) roughly follow their insolubility in water and indicate that π interactions, possible with tryptophan but not with leucine, are not very important in the transport process. The faster transport rate observed with the less hydrophilic tryptophan again suggests that, for II, the pickup of the amino acid by the carrier (rather than the release) is the rate-determining step in the transport process. A comparison of the fluxes for the transport of these amino acids by different carriers across a CHCl3 BLM is shown in Table 1 (flux is defined as: [mmol substrate transported] [mmol carrier]–1 s–1 cm–2.

A comparison of tryptophan, phenylalanine and leucine transporta, by different carriers across a CHCl3BLM.

| Trp | Phe | Leu | Reference |

| 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.01 | b |

| 2.33 | 0.47 | < 0.006 | c |

| N/A | 0.01 | 0.006 | d |

| 24.3 | 16.1 | 21.8f | e |