1 Introduction

The discovery of mesoporous silica materials by Beck et al. in 1992 created tremendous interest in the synthesis of these materials due to their great potential applications in catalysis, separation technologies, drug delivery systems and many other fields [1].

Mesoporous silica materials with good hydrothermal stability such as SBA-15 with thicker pores have been prepared using triblock copolymers as templates. Various other structure directing templates have been used for the synthesis of mesoporous silica materials [2,3]. However, the use of structure directing templates, hydrothermal treatment of the silica precursor and requirement of slow template removal for the preparation of mesoporous silica make the synthesis process quite cumbersome. The synthesis of mesoporous silica using such a tedious process makes the final product quite costly. Hence, a simpler and cost effective synthesis process for mesoporous silica is highly desired for wider applications in catalysis and other applications.

Conventionally a tetraethyl orthosilicate [Si(OC2H5O)4] monomer is used as a silica precursor which on hydrolysis forms a condensed silica product around the structure-directing organic template during synthesis of mesoporous silica materials. Ethyl silicate-40 a polymeric silica [Si(OC2H5O)4]n (n = 4–5) is used as an industrial bulk chemical in the metallurgical industry as a binder in precision casting and other applications [4]. Ethyl silicate-40 being a polymeric silica precursor with moisture sensitive terminal ethoxy groups has been used as a silica precursor in our group for the synthesis of mesoporous silica based catalysts by the simple hydrolysis process without the use of any template and hydrothermal treatment which showed a very high surface area as well as very high acidity. The MoO3/SiO2 catalysts prepared using ES-40 as a silica precursor by the sol–gel method have shown very high activity for typically acid catalyzed transformations like vapor/liquid phase nitration [5], transesterification [6], Beckmann rearrangement [7], condensation-oxidation [8] as well as protection–deprotection of acetals [9], etc.

Esterification of carboxylic acids is one of the important reactions in the preparation of key organic value added intermediates which are widely used as organic solvents, internal plasticizers, perfumeries, paints, foods and pharmaceuticals [10]. Conventional esterification reactions are catalyzed by sulfuric acid/p-toluene sulphonic acid, which poses well-known environmental problems [11] due to liberated hazardous and toxic waste products. To overcome these problems and to satisfy the growing stringent global environmental regulations, the use of solid acid catalysts is highly desired [12]. Various solid acid catalysts have been investigated to replace corrosive mineral acids for esterification of carboxylic acids. Zeolite H-beta [13], ZSM-5 [14], transition metal ion exchanged clays, Nafion functionalized mesoporous MCM-41 silica [15], silicotungstic acid/zirconia immobilized on SBA-15 [16], silica supported sulphonic acids [17], iodine [18], HY-zeolite [19], and heteropolyacids [20] have been investigated for esterification of carboxylic acids with limited success. In the present paper, the MoO3/SiO2 catalysts prepared by the sol–gel method have been used as solid acid catalysts for esterification of mono- and di-carboxylic acids.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Materials

All the reagents viz., ammonium heptamolybdate (AHM), ethyl silicate-40 (CAS registry no. 18945-71-7), isopropyl alcohol, 25% ammonia solution, absolute ethanol, and acetic acid were of AR grade (99.8%); oxalic acid, maleic acid, methanol, 1-butanol, 2-butanol, tert-butanol, hexanol, benzyl alcohol were of AR grade (99.8%) and were obtained from S. D. Fine, LOBA and Merck chemicals, India. The chemicals were used without further purification.

2.2 Catalyst preparation

The catalysts were synthesized using the simple sol–gel technique. Ethyl silicate-40 was used as a silica precursor and ammonium heptamolybdate as a MoO3 precursor for the synthesis of mesoporous silica and MoO3/SiO2 catalysts. The typical synthesis procedures are discussed below:

Pure high surface area silica was prepared by adding 52 g ethyl silicate-40 to 100 g dry isopropyl alcohol; to this mixture 0.02 g ammonium hydroxide solution (25%) was added slowly with constant stirring. The transparent white gel thus obtained was air dried and calcined in a muffle furnace at 500 °C for 5 h.

MoO3/SiO2 catalysts with varying molybdenum oxide molar concentrations (1, 5, 10, 15, and 20) were prepared. In a typical procedure 20 mol% MoO3/SiO2 catalyst was synthesized by dissolving 14.11 g AHM in 40 ml water at 80 °C. This hot solution was added dropwise to the dry isopropyl alcohol solution of ethyl silicate-40 (48.0 g ethyl silicate-40 in 100 ml of isopropyl alcohol) with constant stirring. The resultant transparent greenish gel was air dried and calcined at 500 °C in the air in a muffle furnace for 5 h.

2.3 Characterization

2.3.1 Powder X-ray diffraction studies

The powder X-ray diffraction data of the samples were collected on a Rigaku Miniflex diffractometer equipped with a Ni filtered Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Ǻ, 30 kV, 15 mA). The data were collected in the 2θ range of 10°–80° with a step size of 0.02° and a scan rate of 4° min−1.

2.3.2 Nitrogen adsorption studies

The BET surface area of the calcined samples was determined by N2 sorption at 77 K using NOVA 1200 (Quanta Chrome) equipment. Prior to N2 adsorption, the materials were evacuated at 573 K under vacuum. The specific surface area, SBET, was determined according to the BET equation.

2.3.3 NH3-temperature programmed desorption

Temperature programmed desorption of ammonia (NH3-TPD) was carried out using a Micromeritics Autocue 2910 apparatus. The catalyst was cleaned up at 773 K in a He flow and then cooled to 373 K prior to NH3 adsorption. Then, desorption experiment was carried out at a rate of 10 K min−1 till 873 K.

2.3.4 FTIR of adsorbed pyridine

The nature of the surface acid sites was studied by FTIR of adsorbed pyridine at room temperature. The FTIR spectra of chemisorbed pyridine (py-IR) were obtained in a high-temperature cell (Spectra-Tech) fitted with a Zn-Se window (Shimadzu 8000 FTIR spectrophotometer). The temperature in the cell was varied from 303 to 673 K. The sample (30 mg) was finely crushed and placed in a sample holder. Before pyridine adsorption, the sample was outgassed for 2 h at 673 K under N2 flow to eliminate the adsorbed moisture. The cell was cooled to room temperature and the spectra of the neat catalyst were recorded (100 scans and resolution 4 cm−1) at different temperatures. The sample was dosed with two successive pulses of pyridine (10 μl each). The spectrum was recorded at room temperature after an equilibration time of 30 min. The temperature-programmed desorption of pyridine was studied at 373, 473, 573 and 673 K after equilibration for 30 min after attaining the temperature. The spectrum of the neat sample was subtracted from that of the pyridine adsorbed sample.

2.4 Catalytic activity

A typical esterification of carboxylic acids with alcohols was carried out in a 50 ml two-necked round bottom flask fitted with a reflux condenser. The flask was charged with mono- or di-carboxylic acid, alcohol, and catalyst. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6–8 h (up to maximum conversion) at desired temperature. The reaction was monitored by GC. Samples were withdrawn at regular time intervals and analyzed using a Hewlett–Packard GC model HP6890 with HP (5% cross-linked polyethylene siloxane) column (diameter: 0.53 mm, film thickness: 1 μm, length: 60 m). After completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was cooled and filtered. The products were confirmed by GC–MS (model GC Agilent 6890N with HP-5 and MS Agilent 5973 network MSD, fitted with a 30 m capillary column and GC-IR model Perkin–Elmer Spectrum 2001, column DB and 25m-length 0.32 mm internal diameter).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 XRD

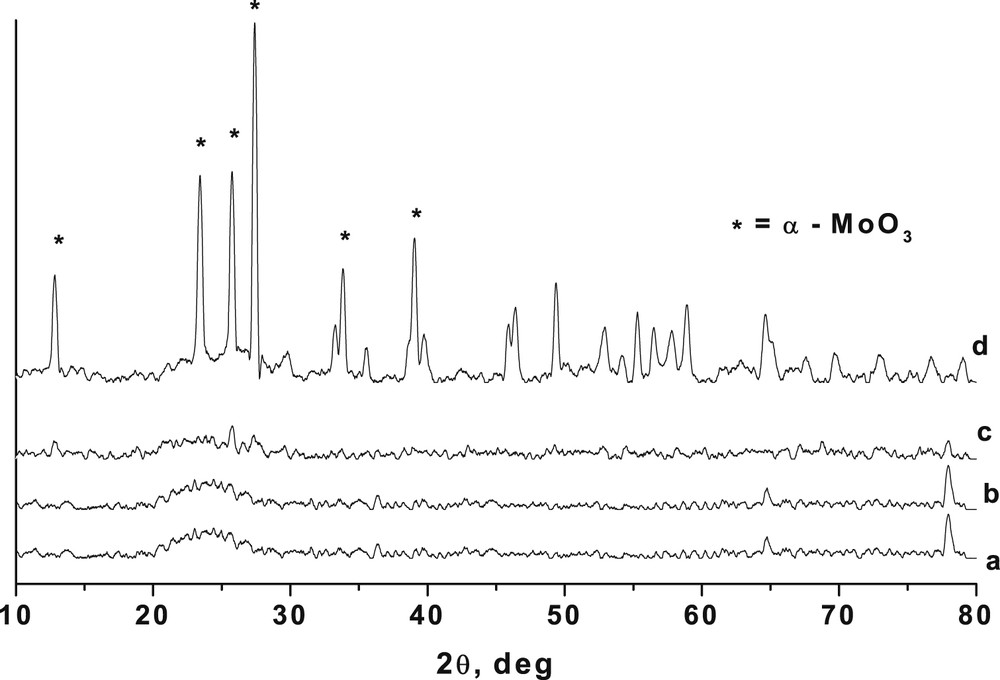

The XRD patterns of 1, 10 and 20% MoO3/SiO2 catalysts prepared by the sol–gel technique are shown in Fig. 1. For comparison, the XRD pattern of pure silica is also included in the figure (Fig. 1a). The patterns showed the amorphous nature of the material at lower Mo loading (Fig. 1b and c) indicating the formation of solid solution or high dispersion of amorphous MoO3 on the amorphous silica support. Catalysts with 20% Mo loading (Fig. 1d) showed a highly crystalline nature with intense peaks at 2θ = 12.9, 23.4, 25.8 and 27.4° corresponding to α-MoO3 in the orthorhombic phase. No β-MoO3 phase was observed in the structure because the samples were calcined at 500 °C, a temperature at which the β-MoO3 phase is not stable [21]. It is interesting to note that even though the MoO3 is in the crystalline form at higher Mo loading, the silica support still retains its amorphous nature leading to the high surface area of the catalysts [6].

XRD of a = silica and MoO3/SiO2 with b = 1, c = 10, d = 20% MoO3/SiO2 loading.

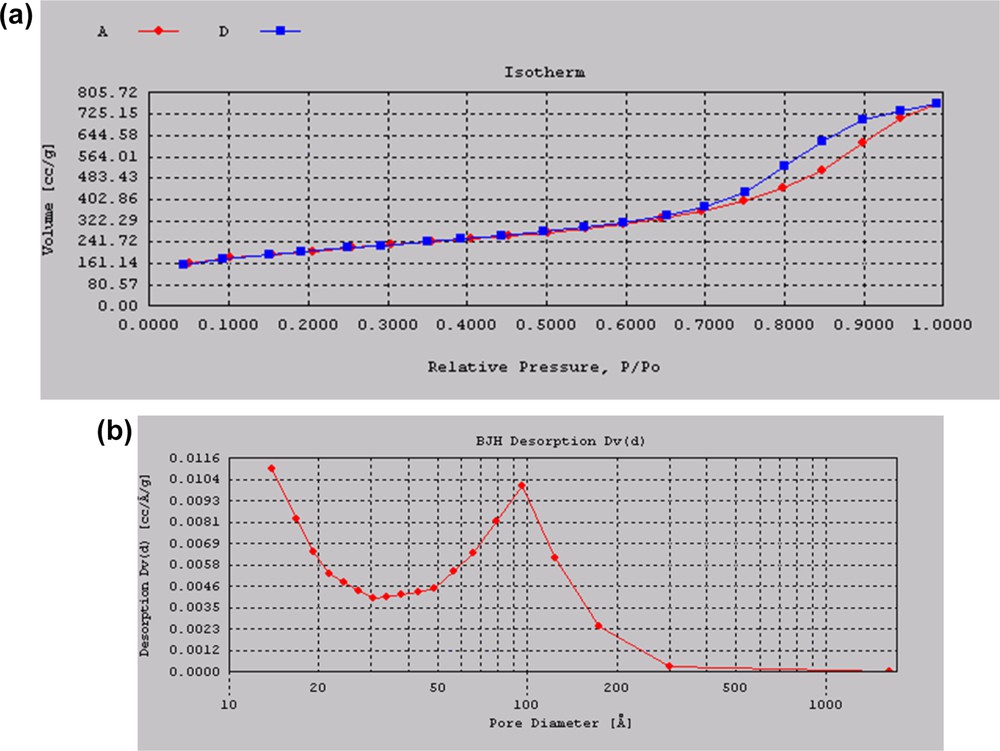

The surface areas of all the catalysts determined using the BET method are given in Table 1. A very high surface area of 719 m2/g was obtained for pure silica prepared by sol–gel synthesis using ethyl silicate-40 as the silica source. A typical H4 type isotherm (Fig. 2a) for mesoporous materials was observed for silica with a broad pore size distribution curve (Fig. 2b) ranging from 10 to 200 Å with an average pore size of 67.3 Å. Ethyl silicate-40 is a polymeric form (trimeric and tetrameric) of tetraethyl orthosilicate monomer, which on controlled hydrolysis yields the silica of a very high surface area [22]. On controlled hydrolysis of ethyl silicate-40, the trimeric and tetrameric species form corresponding trimeric and tetrameric silica species. The trimeric and tetrameric silica species restrict the growth of large particles. The surface area was found to decrease with increase in MoO3 loading. During the sol–gel synthesis, an aqueous solution of ammonium heptamolybdate is added to ethyl silicate-40, which hydrolyzes ethyl silicate-40. However, the control of the rate of hydrolysis is difficult, because of the use of excess water for dissolving ammonium heptamolybdate, which leads to a decrease in the surface area. It is expected that, as MoO3 loading is increased, the crystalline molybdenum oxide clusters are formed that cover the amorphous silica support, reducing the total surface area of the catalyst. However, the catalysts prepared by sol–gel techniques showed a very high surface area as compared to the catalysts prepared by the impregnation method. For 1% Mo loading, the catalyst prepared by the sol–gel technique showed a surface area of 583 m2/g whereas the catalyst prepared by the impregnation method shows a surface area of only 155 m2/g [23].

Textural data and acidity of the catalysts.

| Catalyst | Surface area, m2/g | Pore volume, cm3/g | Pore diameter, Å | NH3 desorbed, mmol/g | Surface density of Mo on support (Dm), nm−2 |

| SiO2 | 719 | 1.19 | 67.3 | 0.03 | 00 |

| 1% MoO3/SiO2 | 583 | 0.59 | 40.7 | 0.18 | 0.0716 |

| 5% MoO3/SiO2 | 432 | 0.63 | 58.2 | 0.56 | 0.483 |

| 10% MoO3/SiO2 | 284 | 0.57 | 79.6 | 0.71 | 1.472 |

| 15% MoO3/SiO2 | 275 | 0.51 | 74.2 | 0.86 | 2.280 |

| 20% MoO3/SiO2 | 180 | 0.23 | 71.64 | 0.94 | 7.891 |

(a) Adsorption desorption isotherm and (b) pore size distribution of silica.

3.2 FTIR studies

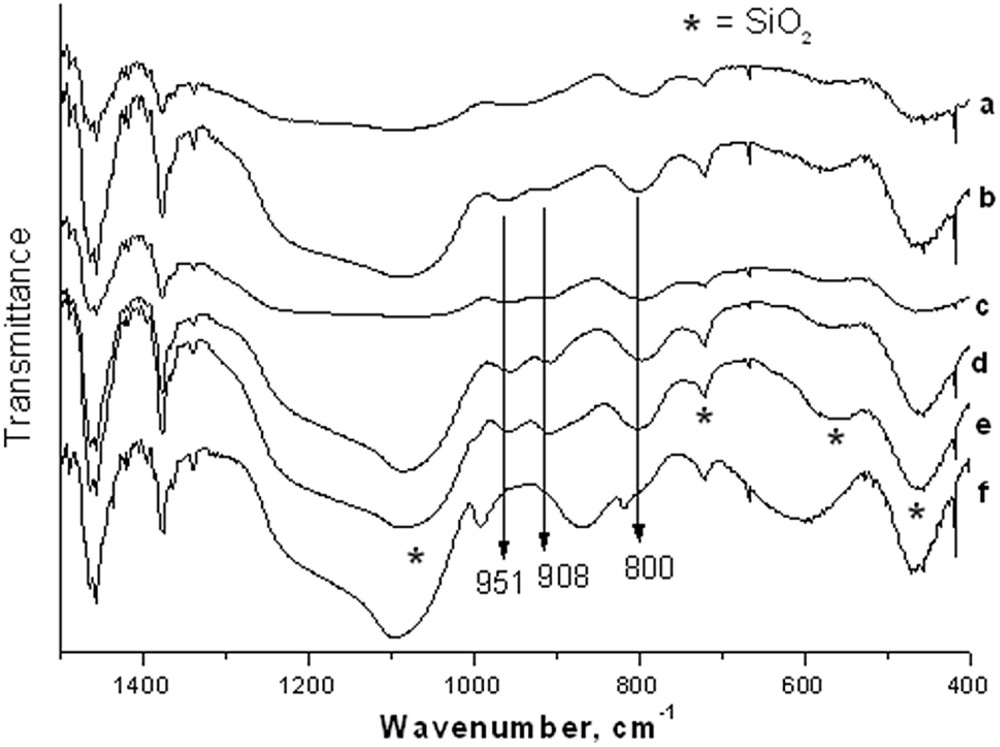

The FTIR spectra of all the catalyst samples prepared by the sol–gel technique are presented in Fig. 3 also confirmed the formation of the α MoO3 at higher loading (main bands at 993, 872, 570 cm−1) whereas the spectra of the 1–5 mol% loading (3 b–e) showed mainly the bands of the silica with those of oxo molybdenum species (908, 951 cm−1) [24].

FTIR spectra of silica (a) and MoO3/SiO2 with 1% (b), 5% (c), 10% (d), 15% (e), 20% (f) MoO3 loading by the sol–gel technique.

3.3 Acidity measurements

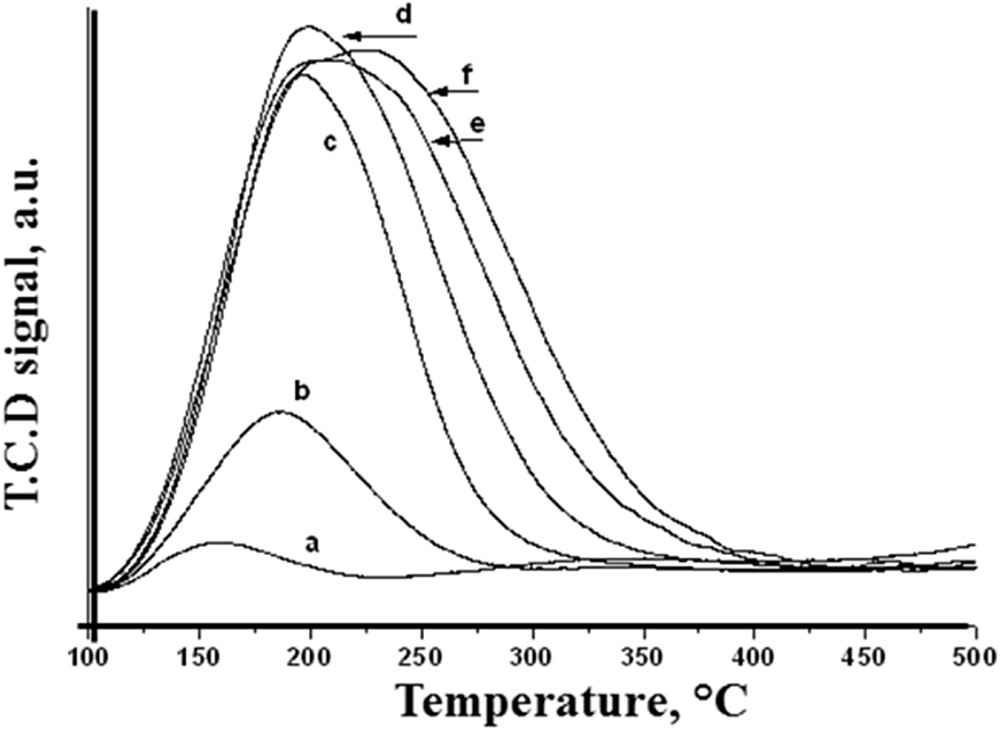

Ammonia-TPD experiments were carried out to determine the acid strength of the catalysts (Fig. 3). The amount of NH3 desorbed is given in Table 1. The pure silica catalyst showed very poor acidity (0.0317 mmol/g NH3) With the increase in MoO3 loading the acidity gradually increased reaching maximum for 20% MoO3/SiO2 (NH3 desorbed: 0.937 mmol/g). Ma et al. [23] have prepared a series of MoO3/SiO2 catalysts (1–16 wt%) by impregnation and the NH3, TPD showed desorption at much lower temperature (<250 °C) indicating the presence of weak acidity. The amount of ammonia desorbed for 1% Mo/SiO2 is reported to be only 0.056 mmol/g which increased to 0.102 mmol/g for 16% MoO3/SiO2. This indicated the significantly low acidity of catalysts prepared by impregnation compared to the catalysts prepared by sol–gel (present work), which is in agreement with the aforementioned increase in dispersion (Fig. 4).

NH3-TPD of (a) silica and MoO3/SiO2 with (b) 1% MoO3 (c) 5% MoO3 (d) 10% MoO3, (e) 15% MoO3 (f) 20% MoO3 loading.

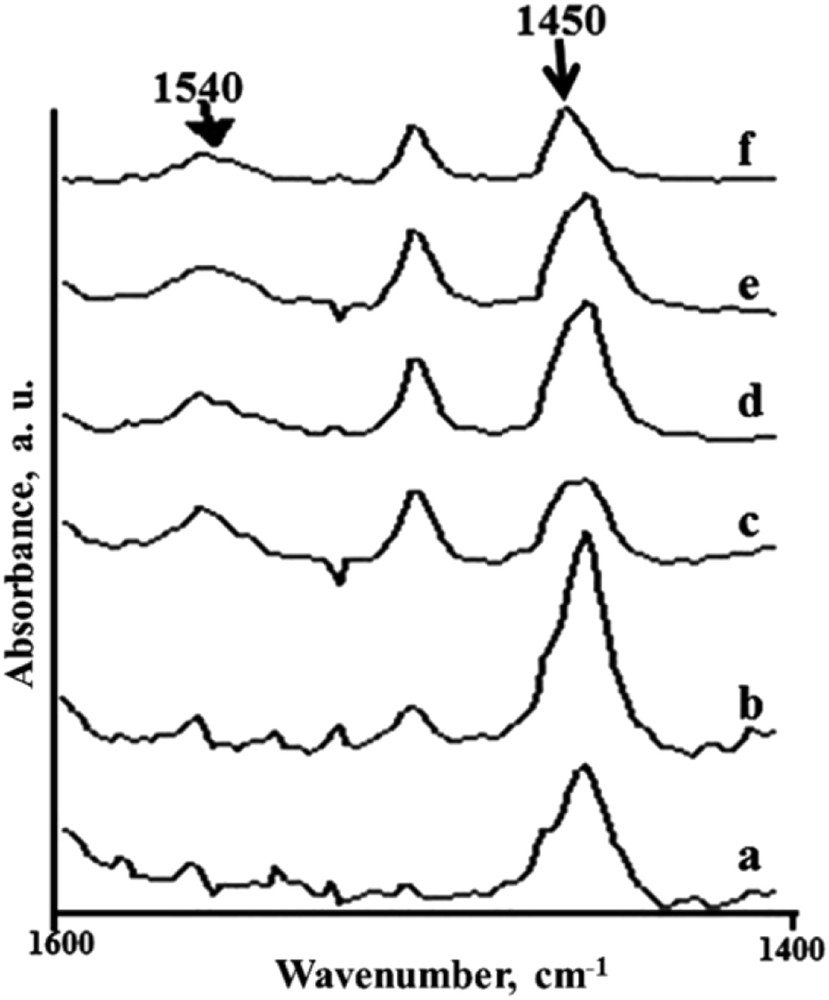

FTIR of adsorbed pyridine as described before [25] revealed the presence of Lewis acidity in all the catalysts. However at higher MoO3 loading the presence of Brønsted acidity was also evident. The generation of Brønsted acidity could be due to the formation of polymolybdate Keggin structures [20] which were evident in FTIR analysis (peaks at 959 and 914 cm−1). All the catalysts were calcined at 500 °C, the temperature at which transformation of hexagonal form of molybdenum trioxide into its orthorhombic form takes place. The oxide becomes hydrated and subsequently converted into polymolybdic trimers [26,27]. Such structural units are expected to show Brønsted acidity. With the increase in Mo loading the ratio of Brønsted to Lewis (B/L) acidity increased (Fig. 5).

FTIR of adsorbed pyridine on (a) pure silica, (b) 1, (c) 5, (d) 10, (e) 15, (f) 20 mol% MoO3/SiO2 at 100 °C after subtracting FTIR of neat catalyst at 100 °C.

3.4 Catalytic reaction

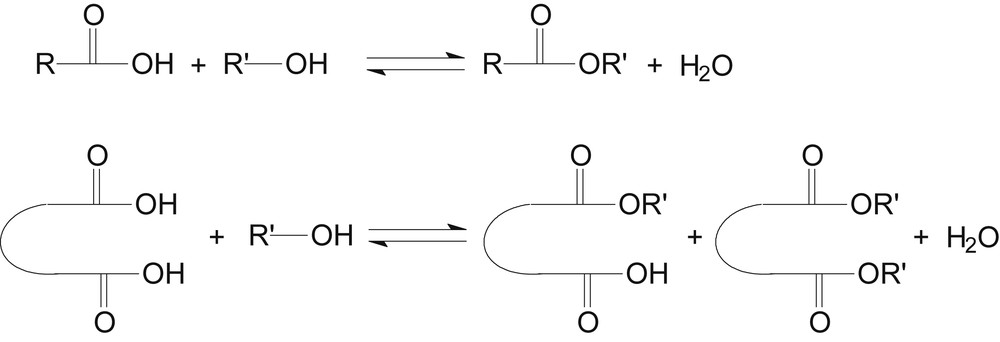

The esterification of mono- and di-carboxylic acid with alcohol is shown in Scheme 1.

Esterification of mono- and di-carboxylic acids with alcohol.

Esterification of acetic acid with methanol was carried out using a series of MoO3/SiO2 with different loadings of MoO3 on silica, and the results are given in Table 2. The results clearly showed an increase in the catalytic activity with an increase in MoO3 loading and the maximum catalytic activity was observed when 20% MoO3/SiO2 was used as the catalyst. As expected the role of the catalyst in this reaction is clearly evident as the conversion without catalyst was only 13.6%. Pure silica was also used as the catalyst, and the conversion was very low (19.6%) comparable with that of the reaction without the catalyst.

Esterification of acetic acid with methanol using different loadings of MoO3/SiO2.

| Sr. No. | Catalyst | Acid conversion, % | Methyl acetate selectivity, % |

| 1. | Blank | 13.6 | 100 |

| 2. | SiO2 | 19.6 | 100 |

| 3. | 1% MoO3/SiO2 | 20.8 | 100 |

| 4. | 5% MoO3/SiO2 | 24 | 100 |

| 5. | 10% MoO3/SiO2 | 35.5 | 100 |

| 6. | 15% MoO3/SiO2 | 48.7 | 100 |

| 7. | 20% MoO3/SiO2 | 53.7 | 100 |

As 20% MoO3/SiO2 showed maximum catalytic activity, esterification of acetic acid with various alcohols was carried out using this catalyst. The results of esterification of acetic acid with various alcohols are shown in Table 3. The conversions varied from 14.7% with tert-butanol to 68% with 2-butanol.

Esterification of acetic acid with different alcohols.

| Sr. No. | Acid | Alcohol | Temp., °C | Conversion, % |

| 1. | Acetic acid | Methanol | 60 | 53.7 |

| 2. | Acetic acid | Ethanol | 70 | 59.0 |

| 3. | Acetic acid | 1-Butanol | 80 | 62.2 |

| 4. | Acetic acid | 2-Butanol | 80 | 68 |

| 5. | Acetic acid | tert-Butanol | 80 | 14.7 |

| 6. | Acetic acid | Benzyl alcohol | 100 | 45.3 |

As the esterification of mono-carboxylic acids was successful, esterification of di-carboxylic acids was also attempted. Initially oxalic acid was esterified with ethanol using different loadings of MoO3 on silica as well as pure silica as the catalyst (Table 4). The conversion without catalyst was very low (10.6%) which increased to 36.3% in the presence of pure silica. Acid conversion with 1 and 10% Mo loadings was 66 and 69%, respectively, which increased to 82.5% in the presence of 20% MoO3/SiO2. In all the cases selectivity for diester was maximum. In the case of di-carboxylic acid also, maximum conversion was obtained with the maximum acidic catalyst. Hence, esterification of di-carboxylic acids with various alcohols was carried out using 20% MoO3/SiO2, and the results are presented in Table 5.

Study of different MoO3 loadings on SiO2 for esterification of oxalic acid and ethanol.

| Sr. No. | Catalyst | Acid conversion | Mono-ester, % | Di-ester, % |

| 1. | Blank | 10.6 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 2. | SiO2 | 36.3 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 3. | 1% MoO3/SiO2 | 66.3 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 4. | 10% MoO3/SiO2 | 69.2 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 5. | 20% MoO3/SiO2 | 82.5 | 21.7 | 78.3 |

Esterification of di-carboxylic acids with different alcohols.

| Sr. No. | Acid | Alcohol | Time, h | Acid conversion, % | Selectivity, % | |

| Mono-ester | Di-ester | |||||

| 1 | Maleic acid | Methanol | 8 | 91.58 | 3.4 | 96.6 |

| 2 | Oxalic acid | Methanol | 8 | 69.7 | 26.6 | 73.4 |

| 3. | Oxalic acid | Ethanol | 1 | 22 | 65.2 | 34.7 |

| 2 | 39 | 56.4 | 43.6 | |||

| 3 | 47.9 | 44 | 56 | |||

| 5 | 64.5 | 39 | 61 | |||

| 8 | 82.5 | 21.7 | 78.3 | |||

| 4. | Oxalic acid | 1-Butanol | 8 | 77.2 | 8.3 | 91.7 |

| 5. | Oxalic acid | Hexanol | 8 | 62.58 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 6 | Oxalic acid | Isopropyl alcohol | 8 | 63.89 | 8.3 | 91.7 |

When esterification of maleic acid was carried out with methanol a very high acid conversion of 91.6% with 96.6% selectivity for diester was obtained whereas no reaction was observed in the absence of catalyst. In the case of esterification of oxalic acid maximum conversion (82.5%) was obtained with ethanol with 78.3% selectivity for diester. The oxalic acid conversion decreased in the series ethanol > 1-butanol > hexanol > isopropyl alcohol with 100% selectivity for diester in the case of hexanol and more than 90% selectivity in the case of 1-butanol and isopropanol. The monitoring of the reaction of oxalic acid with ethanol with time shows that the formation of diester proceeds through mono-ester. Initially selectivity for mono-ester was high and decreased with time whereas the selectivity for diester was increased. Interestingly selectivity for diester in the absence of catalyst was more (100%) though with very low conversion compared to the catalytic reaction. This low conversion may be due to the diffusional constraints in the presence of a catalyst.

The results clearly showed that the 20% MoO3/SiO2 catalyst, which possesses maximum acidity among the series, also exhibited the highest catalytic activity. The catalytic activity observed in the above-mentioned reactions appeared to be correlated with the evolved acidity of the MoO3/SiO2 catalysts.

Most of the esterification catalysts used in organic synthesis are Brønsted acids such as H2SO4, CH3SO3H or heterogeneous Brønsted solid acids. Hence, in the present case, the Brønsted acidity present on the MoO3/SiO2 catalyst is responsible for the high esterification activity. The mechanism of esterification has been studied previously [28]. In the present case, the catalyst with 20% Mo loading showed maximum acidity in terms of the number of acid sites (NH3 desorbed 0.94 mmol/g) as well as acid strength. Esterification has been already reported using cation-exchanged montmorillonite [29]. The catalytic activity is correlated with the electronegativity of exchanged cations, which in turn shows variable polarizability of water molecules coordinated to the cations thus exhibiting protonic (Brønsted) acidity. Similarly, in the present case polarization of water molecules coordinated to Mo center can give rise to protonic acidity essential for the catalysis of the esterification reaction. The nature of catalytically active species in the case of MoO3/SiO2 studied in detail shown in situ formation of silicomolybdic acid associated with silica fine particles to be responsible for the very high acidity of the catalyst [25]. The characterization also revealed the reduction of formed SMA/SiO2 in the presence of water/alcohol rendering blue color to the catalyst. The in situ formation of reduced SMA during the esterification reaction as given in Scheme 2 was responsible for very high acidity and in turn very high activity for esterification.

In situ formation of silicomolybdic acid.

4 Conclusion

Mesoporous high surface area silica has been prepared using ethyl silicate-40 as a silica source using a very simple hydrolysis/sol–gel synthesis process without any use of the organic template and hydrothermal treatment. Ethyl silicate-40, being an industrial bulk chemical, provides a simple and cheaper process for making thermally stable mesoporous silica for catalyst applications. The MoO3/SiO2 catalyst prepared by simple sol–gel synthesis was found to be the very efficient catalyst for esterification of mono- and di-carboxylic acids with a range of alcohols.

Acknowledgments

PM acknowledges UGC for fellowship. Financial support from Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Delhi for the XII FYP project CSC0125 is acknowledged.