Highlights

- ∙ Biosourced silica produced from rice husk waste

- ∙ Ag nanocomposites synthesized by silicon hydride chemistry

- ∙ High removal rates of Hg(II) from water

- ∙ Surface redox reaction between Hg and Ag confirmed

1. Introduction

Water contamination is a global problem and probably the most serious challenge of the 21st century [1]. Heavy metals and especially mercury are the most harmful elements among anthropogenic pollutants. Mercury is widespread in industrial chemicals and to a lesser extent in municipal wastewater and has no known essential biological function [2, 3]. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), the maximum allowable limit of mercury concentration for drinking water is 2 ppb, whereas the World Health Organization set this at 6 ppb [4]. Mercury discharge into water sources has been increasing in Asia, South America and Africa due to mercury use in rapidly expanding industrial activities [5].

Kazakhstan is vulnerable in terms of water resources, and mercury pollution of water is an issue that has been identified for many years [6]. The most characteristic example is the technical reservoir Balkyldak, which is located near the industrial district of Pavlodar city in north Kazakhstan. This waterbody was used for the disposal of liquid industrial wastes of several large-scale plants in Pavlodar. Among them are the Pavlodar Oil Chemical Refinery (POCR) LLP, the Pavlodar Chemical Plant “Caustic” JSC and a heat electric generation plant [7, 8]. Industrial effluents discharged into the reservoir contained various pollutants such as petrochemicals, heavy metals, chlorine, sulfates etc. Studies conducted in the past years in the northern district of Pavlodar showed that the mercury content in soil and groundwater exceeds the allowable limit, which confirms that this region still remains the main focus of mercury pollution in Kazakhstan. Mercury discharges into the Balkyldak reservoir were mainly caused by the “Chimprom” industrial facility, which produced chlorine and sodium through electrolysis with mercury cathodes between 1973 and 1992. For 14 years, approximately 1089 tons of metallic mercury was used. In addition to small discharges of mercury into the waterbody during regular plant operations, there were significant leakages during the shutdown of the plant. Mercury discharge into the aquatic system of the lake Balkyldak has an adverse impact on flora and fauna in the whole region. The analysis of fish from the lake showed that mercury concentration exceeds the maximum allowable limit. The maximum amount of mercury content was found in perch, which was equal to 5.6 times the maximum permissible concentration [7], while the range of mercury concentration in water samples was evaluated to be about 10–100 ppb, with an average of 30 ppb, almost 15 times higher than the USEPA limit in drinking water [8]. The major concern relates to the spread of mercury pollution into the Irtysh River, which is one of the largest waterbodies in Kazakhstan. In the 1950s, mercury pollution from a chemical plant in Minamata Bay caused contamination of fish, which was the main food supply for inhabitants of a modest village. As a result of this human tragedy, 2252 people were affected and 1043 people died. Therefore, the development of efficient mercury remediation technologies is an urgent need [9, 10].

Several methods have been proposed for the removal of mercury from water such as phytoremediation [11], bioremediation [12], ion exchange by use of resins [13], adsorption on activated carbon [14] and natural zeolites [15], membrane filtration [16] and reverse osmosis [4]. A method needs to be inexpensive to be considered viable, and thus low-cost materials are desirable, especially those with high capacity and ability to strongly bind mercury in their structure. Many researchers have considered adsorption as the most advantageous technique for the removal of mercury from water [17]. Activated carbon [18], carbon nanotubes [19], synthetic zeolites [20], zeolite nanocomposites [21], clays and mesoporous silicas [22] have been used for the removal of metal ions, including mercury, from water. Silica is a versatile material with numerous applications [23], particularly suitable for water treatment processes because of its biocompatibility, water insolubility, chemical stability, high mechanical strength and relatively low cost. Alternative sources of silica such as rice husk (RH) and sugarcane bagasse have been used to obtain amorphous silica involving costly chemicals and acid washing under high temperature [24, 25]. For instance, rice husk ash (RHA) with 87.5 % silica content prepared by direct calcination of RH at 650 °C was used to synthesize inorganic silica with Fe and Al ions, which are more favorable in the removal of heavy metals from wastewater [26, 27]. Different optimization approaches have been used to improve the adsorption capacity of silica. For instance, Katok et al. [28] reported the synthesis of composite materials by immobilization of silver nanoparticles on the silica surface functionalized with hydride groups. They examined the potential application of silicon hydride composites as adsorbents for mercury from aqueous systems. These novel adsorbents demonstrated high reactivity and capacity and can be effective candidate materials for removing mercury ions.

Generally, owing to mercury’s properties, the physical adsorption on conventional adsorbents is not effective. In the majority of cases, the adsorbent’s surface must be modified to enable chemical adsorption [29, 30, 31]. It has been reported that several metals, such as palladium, platinum, rhodium, titanium, gold, zinc, aluminum, copper and silver are able to form amalgams with mercury [32, 33, 34, 35, 36]. Moreover, these metal amalgams formed with mercury have low solubility, which implies negligible release of mercury after adsorption. Silver–mercury has the lowest solubility, and it has been preferred for the modification of several adsorbents [2, 33, 37]. Since the reduction potentials of silver (Ag+ + e−⟶Ag0) and mercury (Hg2+ + 2e−⟶Hg0) are 0.8 V and 0.85 V, respectively, the redox reaction between bulk metals is not expected to happen. Silver is relatively cheap and easy to use in the modification of materials [38]. However, nanoscale silver has been proven to be more reactive because of a decrease in reduction potential when the silver nanoparticles are smaller, leading to Hg0, which reacts with Ag0 to form an amalgam [2, 39]. The method of silver nanoparticle immobilization on the surface of modified silica, which is used in the present work, has several advantages over other techniques as it has a relatively low cost since it requires small amounts of the silver nitrate solution and no reductants and silica can be synthesized using RH as a raw material [25].

The present paper explored the preparation and characterization of a new effective nanocomposite prepared from biosourced silica coming from agricultural waste to remove aqueous mercury ions from aqueous solutions. The use of silica as an adsorbent not only contributes to the solution of a pressing water contamination problem but also expands the feasibility of turning an agricultural byproduct into a valuable resource. Biosourced and agricultural-waste-derived materials being used for environmental applications is a promising solution for sustainable waste management and preservation of the environment [40, 41, 42], and nanocomposites offer opportunities for the utilization of a variety of substrates [43]. The Hg–Ag amalgamation reaction has been rarely observed at the nanoscale [39]. The present study aims to contribute to this new research area with further evidence of the phenomenon and a more robust mechanism of Hg–Ag interaction based on experimental evidence.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and chemicals

Triethoxysilane (TES, Sigma Aldrich, 390143, 95%), acetic acid (glacial), silver nitrate and mercury chloride were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and used without further purification. Raw husk was used as the raw material for synthesizing silica from south Kazakhstan. Ultrapure (UP) water of resistivity 18.3 MΩ⋅cm was used for all solutions.

2.2. Synthesis of nanocomposites

2.2.1. Synthesis of silica

The samples of RHs were previously washed with water for the purification of the composition from foreign substances. The raw materials were dried in the laboratory bench oven at the temperature of 90 °C for 2 h for complete evaporation of the water content. All dried samples (50 g) were calcinated at 600 °C for 4 h in a muffle furnace (AAF series, Carbolite) to produce white rice husk ash (WRHA). After the end of the calcination, all organic compounds in the RH are burned off completely. The WRHA was mixed with 100 ml of 2 M NaOH at 90 °C under continuous vigorous stirring for 2 h to extract the solid silica into water soluble sodium silicate. The sodium silicate solution was then filtered through the 0.45 μm acetate cellulose membrane filter to remove insoluble residues. After filtration, the sodium silicate solution (the filtrate) was converted into insoluble silicic acid via reaction with concentrated HCl for 30 minutes, under continuous stirring. Precipitated silica oxide was washed extensively on a filter with UP water until neutral pH, dried in the bench oven for 8 h at 105 °C and the resulting sample was named RH-SiO2. More details on the synthesis of silica can be found elsewhere [25].

2.2.2. Silica modification by TES

In total, 3 g of the RH-SiO2 sample was added into a round bottom flask equipped with a reflux condenser. The flask was placed in a water bath at constant temperature (90 °C), and 0.46 ml of TES in 60 ml of glacial acetic acid was added under continuous stirring. After 2 h of reaction, the mixture was cooled to room temperature and filtered. The obtained solid was dried at 90 °C. The resulting modified silica samples were used for silver nanoparticle impregnation. This sample was named TES-SiO2. The silicon hydride (SiH) group concentration was measured by iodometric titration [44].

2.2.3. Silver nanoparticles impregnation

Samples of modified silica (1.1 g each) were immersed in different volumes (11, 22, 33, 44 ml) of aqueous silver nitrate solution (10 mmol/L) at ambient temperature. The modification was carried out in the dark to prevent oxidation of the silver nitrate. Silver nanoparticles are formed on the surface of silica through chemical reduction of silver ions into the zero-valence state as a result of reaction with silicon hydride groups. The obtained samples were filtered and dried for 12 h at 105 °C in the bench oven.

Moreover, in order to examine the stability of silicon hydride groups in water, TES-SiO2 was immersed in water for 24 h and analyzed by iodometric titration.

2.3. Mercury removal experiments

The AgNPs@SiO2 nanocomposites and the parent TES-SiO2 were tested for the removal of mercury from a mercury chloride (HgCl2) solution of 100 mg∕L concentration. In all experiments, 0.1 g of the nanocomposite was added in a conical flask containing a 10 ml solution. The mixture was continuously shaken at ambient temperature for 1.5 h and then centrifuged and the solution analyzed for mercury. The kinetic experiments were done in triplicate.

2.4. Material characterization and analytical methods

Fourier Transform infrared spectra (FTIR) were recorded on Agilent technologies, Cary 600 series FTIR spectrometer in transmission (T) mode at a wavenumber range 500–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 2 cm−1. The powder was then dispersed and X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using the Rigaku (SmartLab® X-ray) diffraction system with a Cu Kα radiation source (𝜆 = 1.54 Å) at a scan rate of 0.02° θ⋅s−1 in the 2θ range of 5–90°. Adsorption characteristics of samples were obtained from N2 low-temperature adsorption/desorption isotherms by using an Autosorb-iQ Automated Gas Sorption Analyzer. The isotherms were recorded in the range of relative pressures, p∕p0, from 0.005 to 0.991. Samples were outgassed for 10 h at 150 °C prior to the measurements to remove any moisture or contaminants adsorbed. The Autosorb-iQ software was used to calculate BET (SBET) and BJH (SBJH) specific surface areas of samples by applying the BET/BJH equation to the adsorption data. The thermal properties of samples were measured by thermogravimetric analysis using a TG/DSA 6000 instrument (Perkin Elmer 6000 simultaneous thermal analyzer) in the heating range from 50 to 950 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min. A transmission electron microscope (JEOL JEM-2100 LaB6) was employed to investigate the morphology and size of the synthesized silver nanoparticles. The particle size distribution of the samples was analyzed on the Mastersizer 3000 (Malvern) instrument. The mercury concentration in aqueous samples was analyzed by RA-915M Mercury Analyzer (Lumex-Ohio) with pyrolysis attachment (PYRO-915+).

Porosimetry results

| Sample | SBET (m2 g-1) | SBJH (m2 g-1) | VPa (cm3 g-1) | dmaxb (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RH-SiO2 | 980 | 418 | 1.086 | 3.055 |

| TES-SiO2 | 285 | 166 | 0.895 | 4.723 |

| 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 | 310 | 160 | 0.863 | 5.072 |

a VP represents the BJH cumulative desorption pore volume in the maximum diameter range 1.7–300 nm.

b dmax is the maximum pore size of the pore distribution derived from the adsorption branch.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Material characterization

Silicon hydride groups anchored to the surface of silica particles possess weak reducing properties, which are sufficient for generating chemically pure zero-valent silver by the reduction of silver cation according to the following reaction [39]:

On addition of Ag+, bubbling was observed, indicating the release of H2 gas. Iodometric titration showed a concentration of SiH groups equal to 0.73±0.03 mmol∕g (n = 3). The concentration of SiH groups was proven to be sufficient for the complete removal of Ag from the solution, and based on the experimental conditions, the different concentrations of silver nanoparticles on silica substrate were 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mmol Ag/g SiO2. The complete removal of Ag+ from the solution was proved by AgCl test. Furthermore, the Si–H groups were proved to be very reactive as they disappeared after contact with water. This is due to the following reaction [28]:

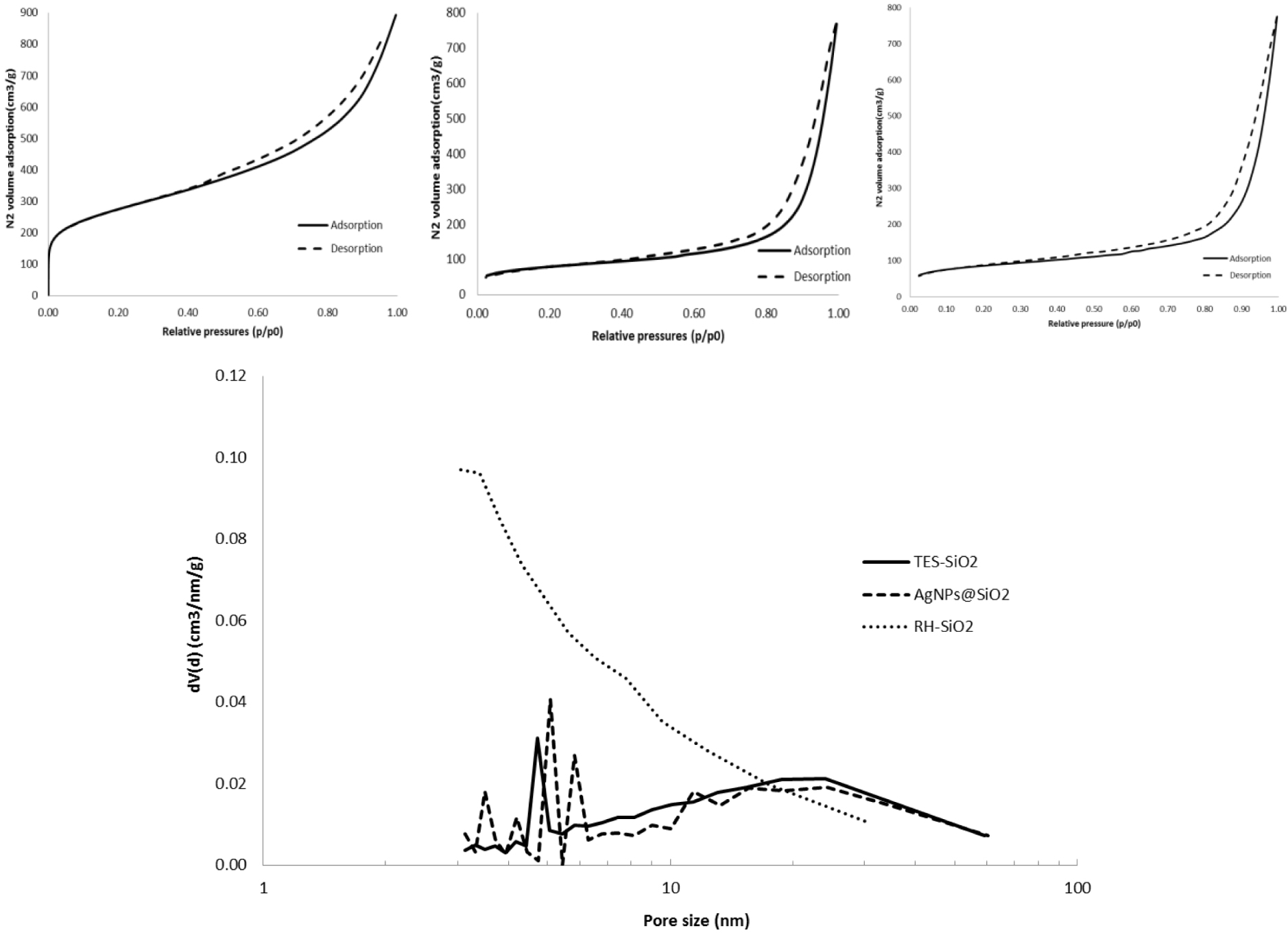

3.1.1. Porosimetry

The RH-SiO2 and TES-SiO2 samples and the silver sample with the highest loading (0.4 mmol/g) were studied in order to investigate potential blocking of the substrate’s pores. Table 1 shows the results of the low-temperature nitrogen adsorption porosimetry.

The TES-SiO2 and AgNPs@SiO2 samples have a much lower specific surface area than the initial RH-SiO2 sample. This should be a result of the TES modification of the sample, which seems to partially cover the silica surface and block the pores. The decrease in the pore volume of the modified samples supports this observation. The surface area of all samples is considerably higher than those reported in the literature for biosourced RH-derived silica. For instance, Chaves et al. [45] reported values between 30 and 153 m2∕g for untreated and silane-modified silicas.

According to IUPAC classification, the isotherms can be classified as Type II or Type III, indicating non-porous or macroporous materials [46]. The H3 hysteresis loop is an indication that the material is composed of agglomerates or it has slit-shaped pores [47]. However, pore size distribution analysis showed some microporosity and mesoporosity for the RH-SiO2 sample and mesoporosity for TES-SiO2 and AgNPs@SiO2 samples (Figure 1). The microporosity of RH-SiO2 is also evidenced by the shape of the isotherm in the low pressure region (P∕P0⩽0.1), which disappears in the modified samples. This can be attributed to the blocking of micropores during the RH modification process. The BJH mean pore diameter reported by Chaves et al. [45] is between 21.2 and 21.8 nm for untreated and silane-modified silicas.

Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of RH-SiO2 (upper left), TES-SiO2 (upper middle) and 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 (upper right) and pore size distribution of samples (lower).

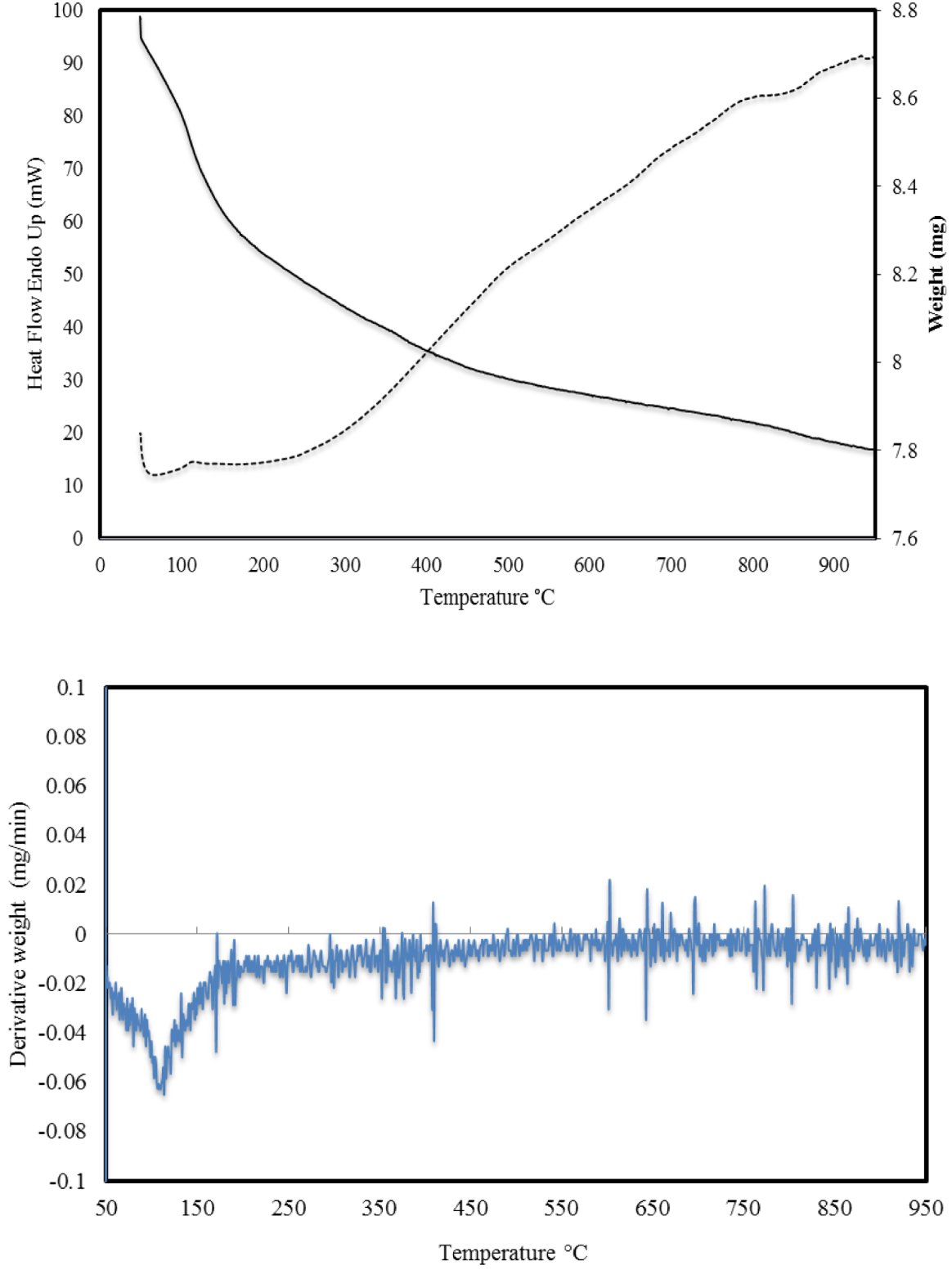

3.1.2. Thermogravimetric analysis

The thermogravimetric analysis of the RH-SiO2 sample is shown in Figure 2.

Thermograph of RH-SiO2.

From the results, it follows that when the sample was heated to 950 °C, a monotonic mass loss occurred throughout the entire temperature range. In the first heating section up to 100 °C, the sample loses 2% of the mass due to evaporation of water from the structure of the sample, which is evident from the energy consumption curve (dotted line) and the DTA curve (lower figure). There is a gradual loss of mass, but starting from 300 °C, a sharp consumption of energy begins, which indicates the burning of the remaining carbon in the structure of the silica. It can be concluded that the RH-SiO2 sample is relatively heat-resistant and the total weight loss is 11.36%. The TES-SiO2 and 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 samples showed very similar behavior with weight losses of 15.87% and 12.44%, respectively, which indicates that the modifications had no substantial effect on the thermal properties of the materials.

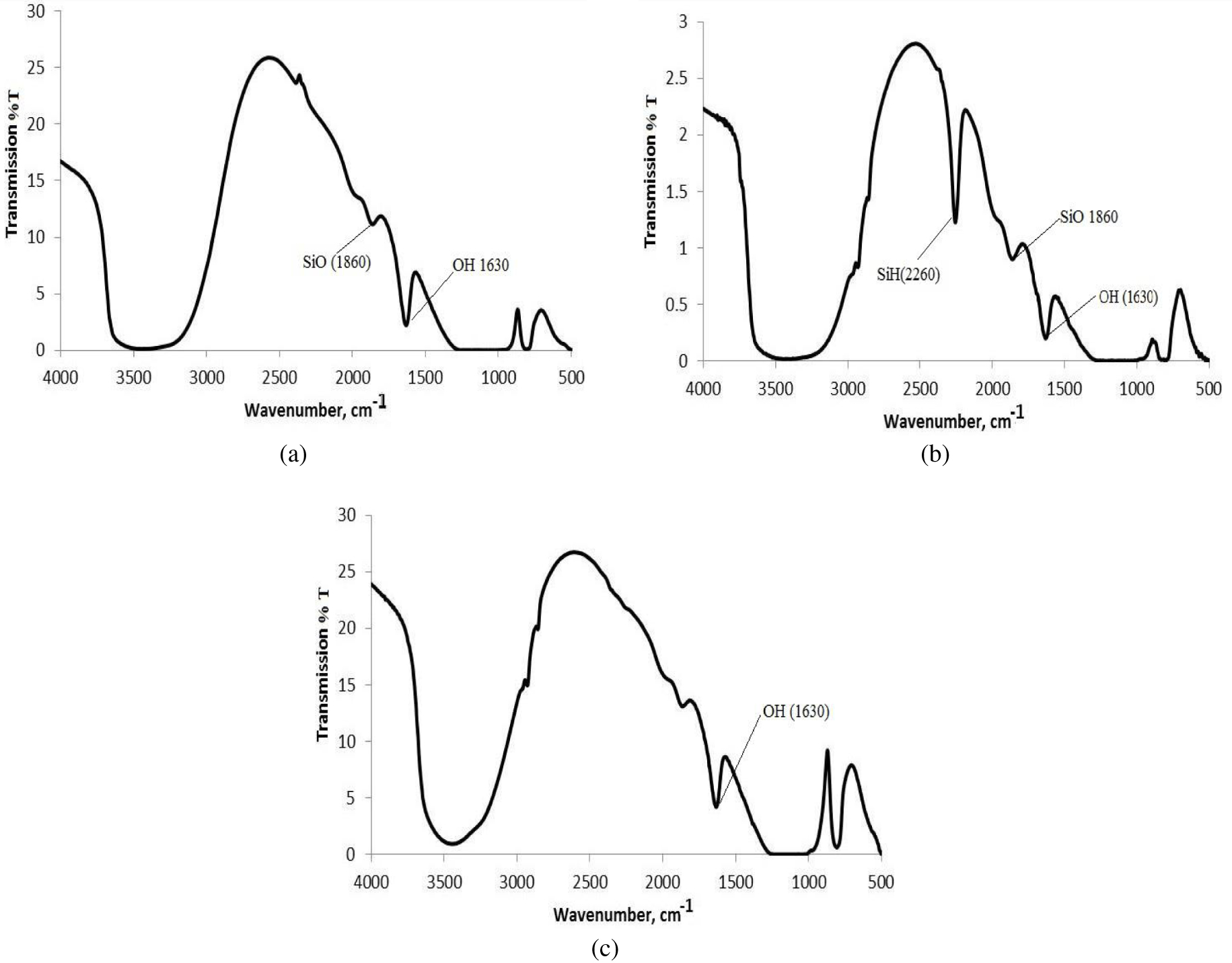

3.1.3. FTIR results

The FTIR spectra of pristine, TES-modified and 0.3 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 samples are shown in Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of (a) RH-SiO2, (b) TES-SiO2 and (c) AgNPs@SiO2.

The FTIR spectra of silica samples are characterized by the presence of a broad absorption band at 3600–3000 cm−1 corresponding to the O–H vibrations in adsorbed water molecules and silanol groups of the silica surface and a very strong band between 1050 and 1200 cm−1, which can be attributed to the stretching band of silanol. Additional bands of silanols can be observed at 870, 1630 and 1860 cm−1 [48]. After the modification of silica with TES, the SiH absorption band with maximum at 2260 cm−1 appears in the spectra (Figure 3b). This band corresponds to Si–H bond stretching vibrations [49] and disappears after reaction with the silver nitrate (Figure 3c).

3.1.4. Particle size distribution of initial and silane-modified silica samples

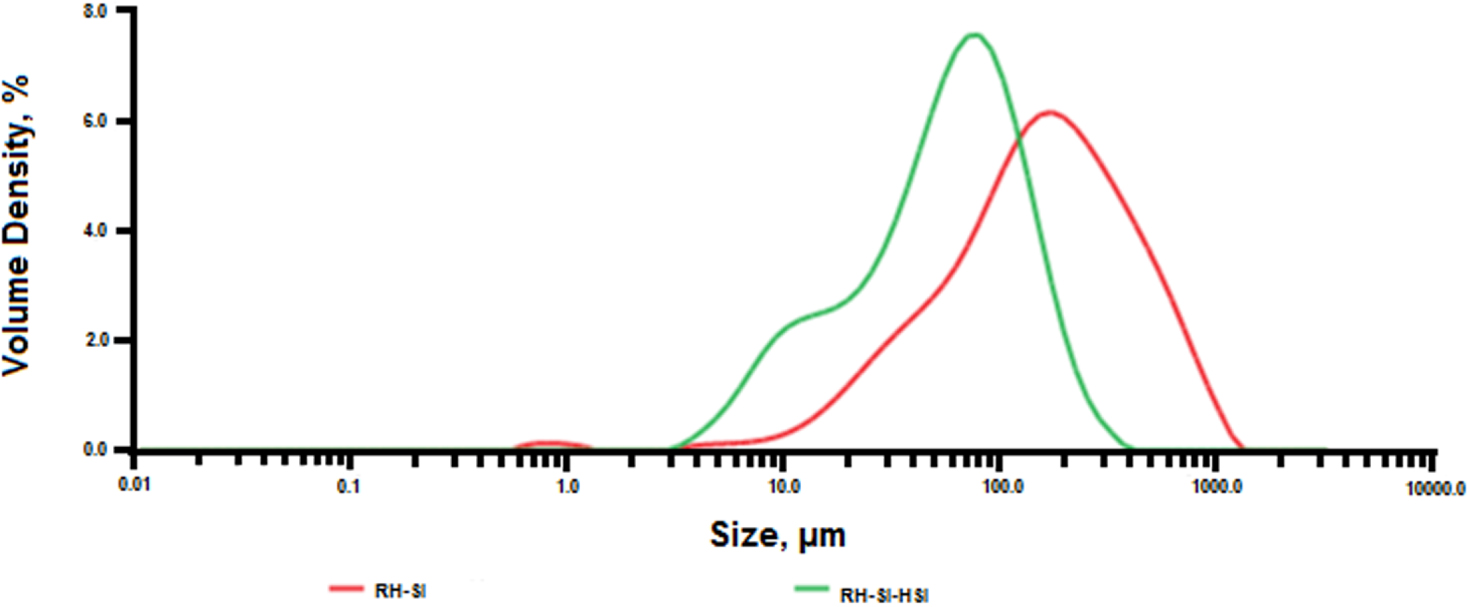

Figure 4 shows the particle size distribution of RH-SiO2 and TES-SiO2 samples.

Particle size distributions of RH-SiO2 (right curve) and TES-SiO2 (left curve) samples.

From the obtained data, it follows that in the initial sample the particle size is in the range from 10 to 1000 μm, with a maximum at 200 μm. However, when the initial sample was modified with TES, the particle size was reduced with a maximum at 70 μm, with the particle size distribution ranging from 3 to 400 μm. These changes were due to the modification of the initial sample at 90 °C, which ultimately led to either disaggregation or fusion of silica particles. This corroborates the drastic decrease in the surface area of TES-SiO2 (Table 1) due to some porosity loss.

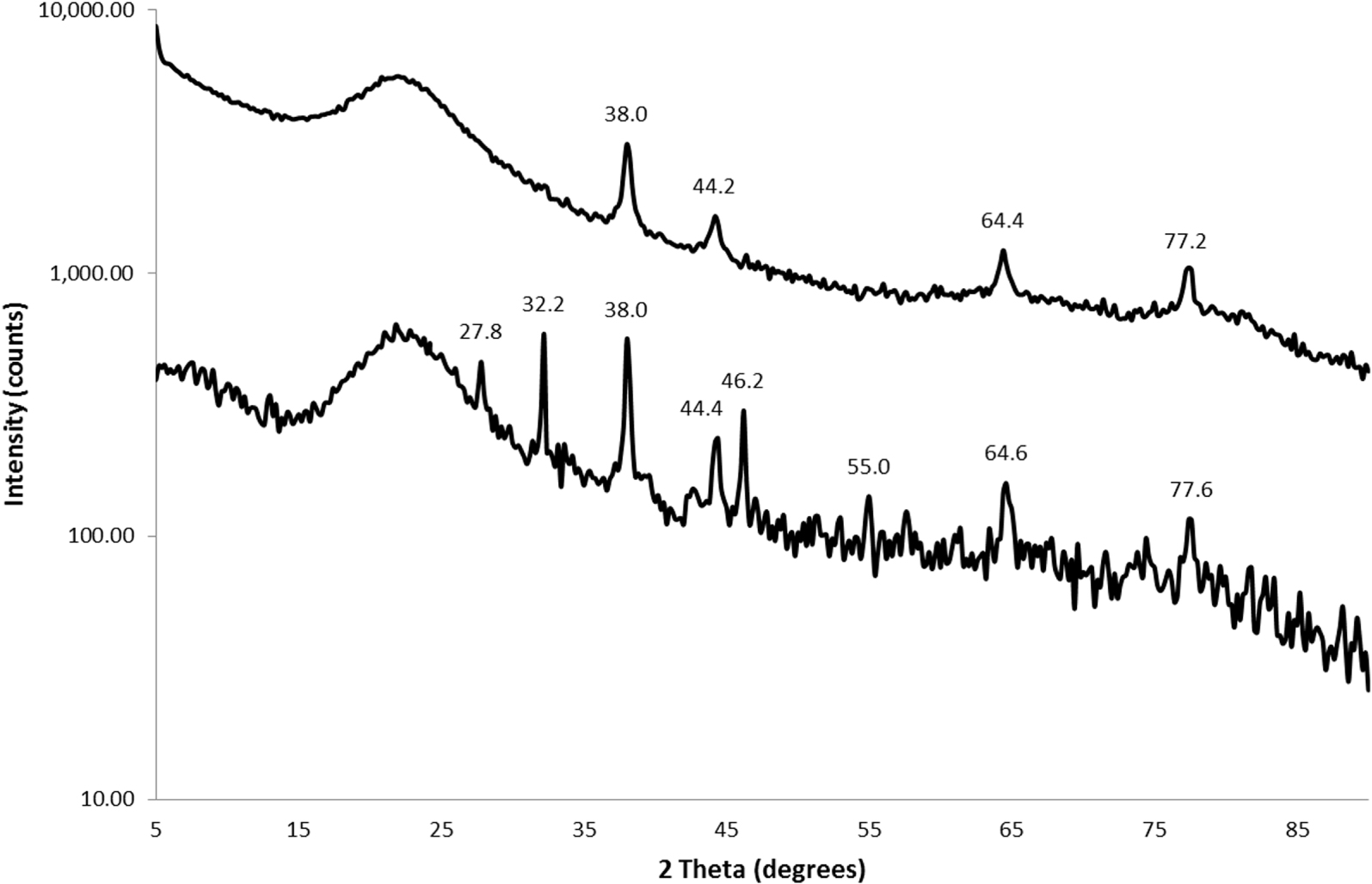

3.1.5. XRD results

The analysis of the AgNPs@SiO2 nanocomposites is shown in Table 2 and Figure 11 for the 0.3 mmol/g sample. The samples show the major peaks of Ago, which confirms the successful formation of silver nanoparticles that have a face-centered cubic crystalline structure. The halo with a maximum at 1° θ corresponds to amorphous silica. The NPs size was calculated using the Debye–Scherrer equation and found to be between 43.08 and 56.63 nm without any trend for different Ag samples.

XRD results of 2-theta (deg) of AgNPs@SiO2 at different Ag loadings

| 0.1 mmol/g | 0.2 mmol/g | 0.3 mmol/g | 0.4 mmol/g | Phase name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.50 | 22.12 | 21.96 | 21.10 | Amorphous silica |

| 38.131 | 38.21 | 38.01 | 38.00 | Silver (1,1,1) |

| - | - | 44.18 | 43.801 | Silver (2,0,0) |

| 64.101 | 64.30 | 64.38 | 64.80 | Silver (2,2,0) |

| - | 77.02 | 77.16 | 78.40 | Silver (3,1,1) |

1 Very weak peaks

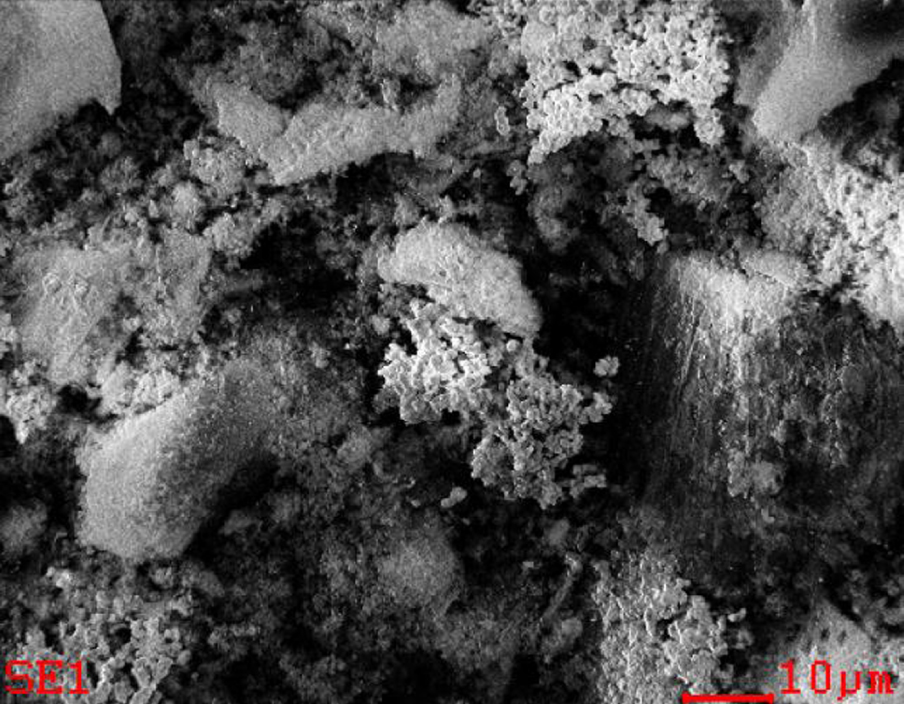

3.1.6. SEM and TEM results

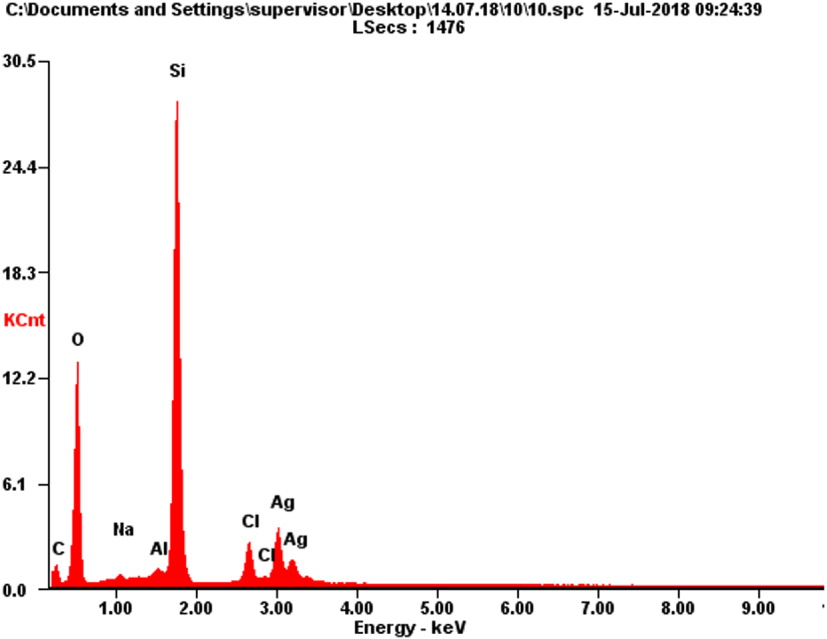

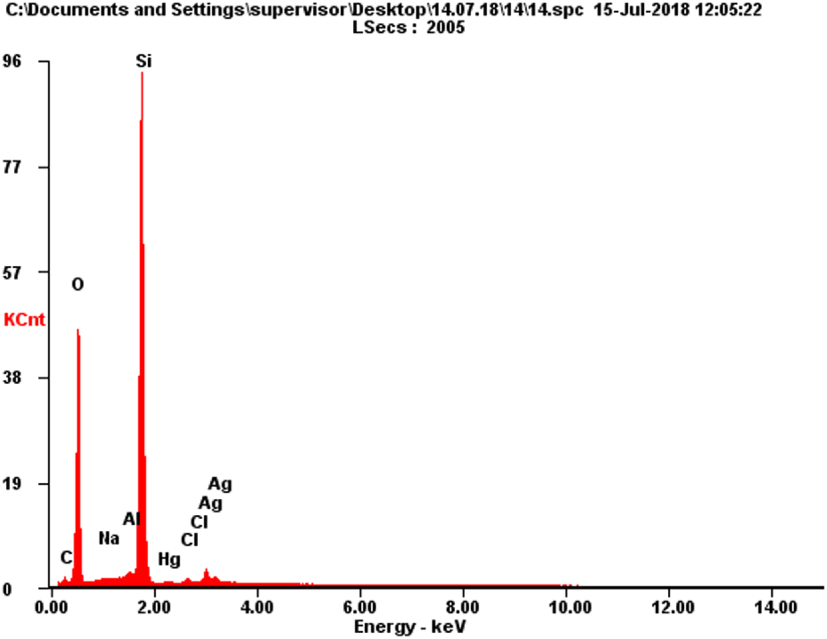

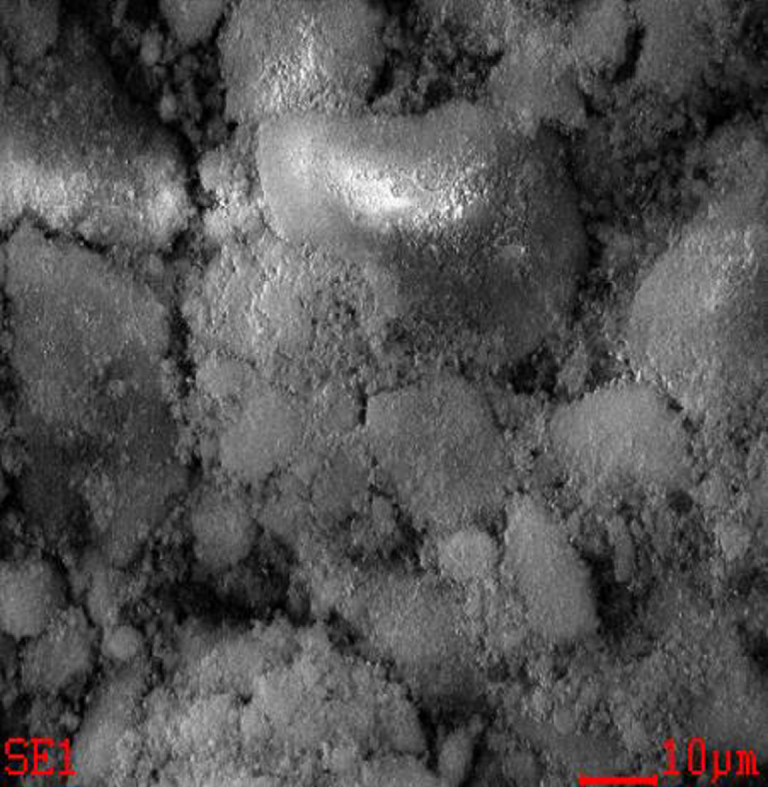

A typical SEM/EDX (scanning electron microscopy /energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy) analysis is shown in Table 3 and Figure 5 and confirms the presence of silver on the silica surface.

Results of energy-dispersive X-ray spectral microanalysis of 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2

| Element | Wt % | At % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 3.02 | 6.42 |  | |

| O | 29.20 | 46.60 | ||

| Na | 0.56 | 0.62 | ||

| Al | 0.90 | 0.85 | ||

| Si | 40.69 | 36.99 | ||

| Cl | 5.06 | 3.64 | ||

| Ag | 20.57 | 4.87 | ||

SEM image of 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2.

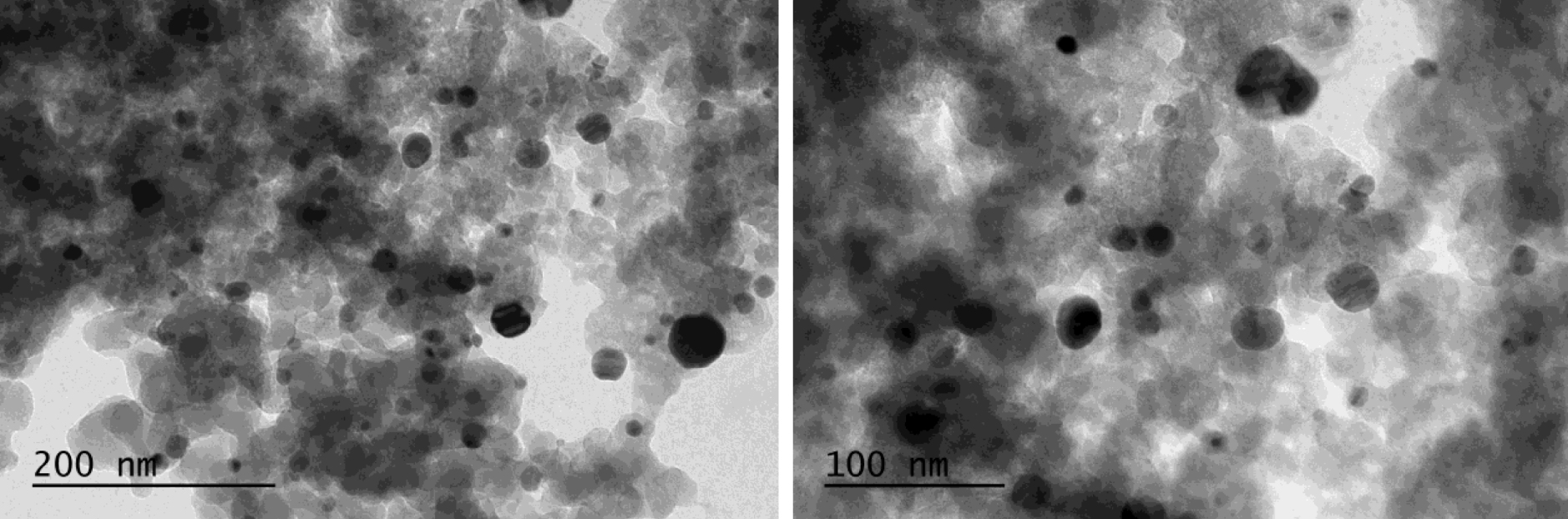

TEM images of 0.2 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 after interaction with Hg.

Results of energy-dispersive X-ray spectral microanalysis of silver decorated silica after interaction with Hg (0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2)

| Element | Wt % | At % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | 1.84 | 3.46 |  |

| O | 35.63 | 50.47 | |

| Na | 0.16 | 0.16 | |

| Al | 0.76 | 0.63 | |

| Si | 53.77 | 43.38 | |

| Hg | 0.67 | 0.08 | |

| Cl | 0.70 | 0.45 | |

| Ag | 6.48 | 1.36 | |

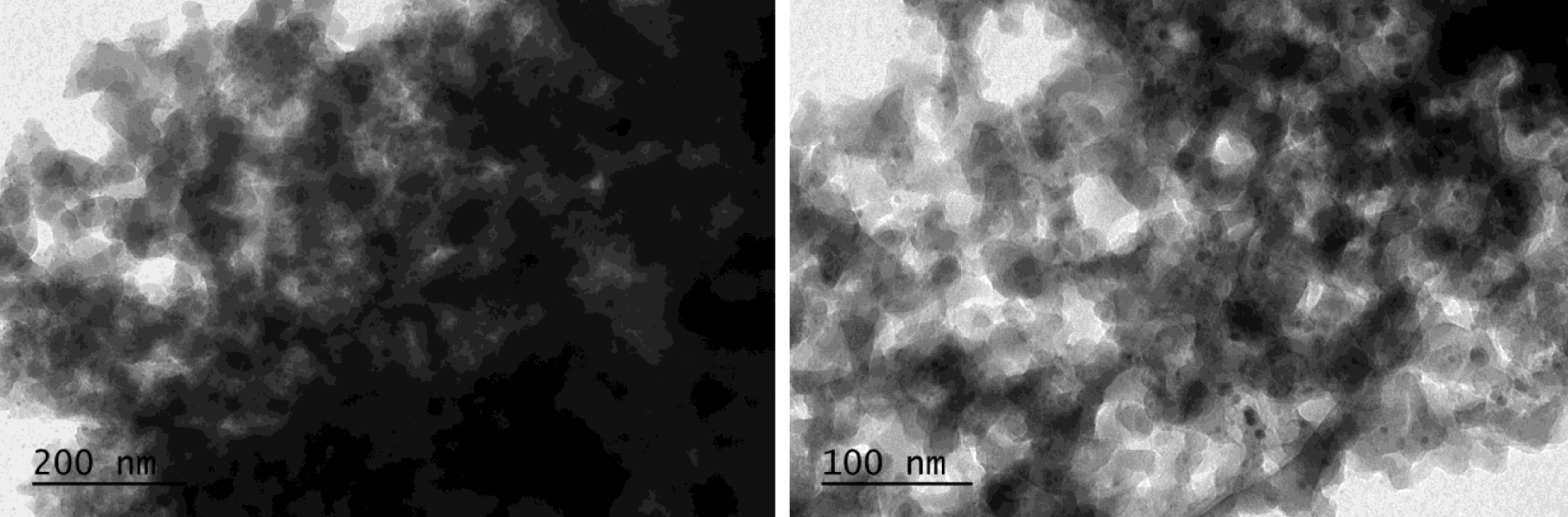

Figure 7 shows characteristic TEM (transmission electron microscopy) images of the nanocomposites with NPs of near-spherical shape and varying sizes from 4 to 60 nm. It is also seen from the images that the particles are not aggregated but spread over the surface of the silica. The reason is that AgNPs appears only at those sites where the silicon hydride groups are present. Moreover, the surface density of the SiH groups is small, which also prevents the agglomeration and the stability of the generated nanoparticles.

3.2. Mercury removal experiments

TEM images of 0.2 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2.

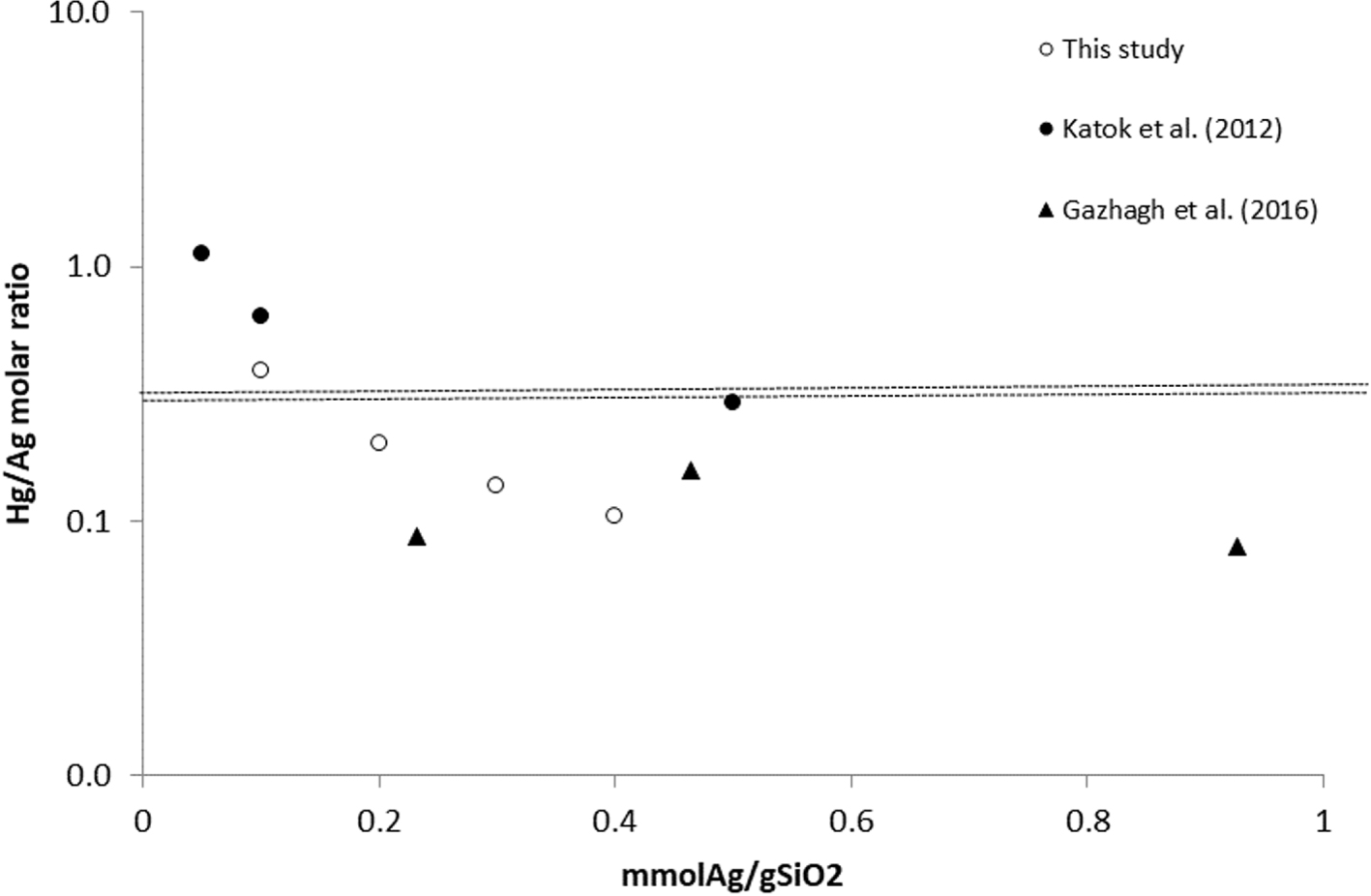

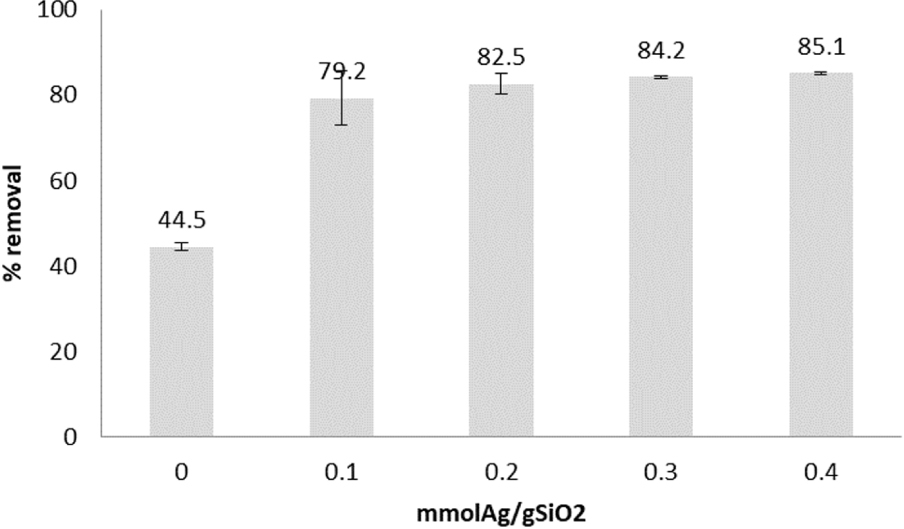

Mercury removal achieved by TES-SiO2 and AgNPs@SiO2 samples is shown in Figure 8 and the calculated molar Hg/Ag ratio in Figure 9. The Hg/Ag molar ratio based on the Hg2+ removed from the solution and the initial Ago on the material is between 0.104 and 0.388. The dotted lines mark the expected theoretical stoichiometric values if amalgams are formed (0.31 and 0.375). Hg/Ag molar ratios lower than the theoretical stoichiometric values show that either not all of the Ago reacted or the amount of Hg2+ in the solution was not sufficient to consume all Ag0.

Hg2+ removal (0 mmolAg∕SiO2 is the TES-SiO2 sample).

As is evident, the TES-SiO2 sample removes a considerable amount of Hg. This is not surprising as the Hg–H interaction has been reported in previous studies and follows the reaction [28]:

According to Katok et al. [39], mercury ions in solution interact with silver metal (Ag0) at a theoretical Hg/Ag stoichiometric ratio of 0.5 resulting in zero-valent mercury [39]:

Based on this stoichiometric ratio, Katok et al. described a hyperstoichiometric effect, according to which the Hg/Ag molar ratio changes depending on the AgNPs size. However, this is only part of the overall mechanism as redox is followed by other reactions, including amalgamation. The Hg2+ reduction and amalgamation were observed by Henglein and Brancewicz [50] and Henglein [51], who suggested the following reaction mechanism between Hg2+ and AgNPs:

Harika et al. [52] studied the amalgamation reaction by ultrasonically reacting liquid mercury with an aqueous solution of silver nitrate. Although the formation and role of silver nanoparticles is not discussed, the authors observed schachnerite and moschellandsbergite and mixed phases with molar Hg/Ag ratios of 0.665 to 2. Assuming the 0.5 ratio in the redox reaction and the formation of moschellandsbergite, the overall reaction is:

In the case of schachnerite:

Thus, under the condition that all Ago reacts, physical adsorption is negligible or subtracted and one of the above amalgamation reactions occurs, the overall stoichiometric Hg/Ag molar ratio must be between 0.31 and 0.375 depending on the amalgam formed. However, other compounds might be formed, such as Hg2Cl2 and HgO, in which case the Hg/Ag molar ratio can be up to 1. Regardless of the Hg removal mechanism and the presence of hyperactivity effect, there seems to be scaling of the Hg/Ag ratio with the silver content, and the phenomenon requires further investigation.

There are only few publications on the formation of Hg–Ag amalgams at the nanoscale [52]. Besides the complexity of the reaction, another issue is that the identification of the amalgams by XRD in small concentrations is difficult and only few weak peaks are typically observed; see for example Katok et al. [39], who first investigated hyperstoichiometry in a similar system and identified schachnerite. The same amalgam was observed by Henglein and Brancewicz [50], but the reaction was between Ag+ and Hg2+ solutions in the presence of a reducing agent. A comprehensive study on the formation of amalgams between bulk Hgo and Ag nanoparticles is that by Harika et al. [52]. The results showed that depending on the initial Hg/Ag molar ratios, no amalgam, schachnerite, moschellandsbergite and mixed schachnerite/moschellandsbergite can be formed.

X-ray diffraction patterns for silver nanoparticles on silica substrate synthesized from 0.3 mmol Ag/g SiO2 concentration of silver (upper curve) and after interaction with Hg (lower curve).

The XRD spectra of a 0.3 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 nanocomposite sample after interaction with mercury are shown in Figure 10, and the peaks identified in the other nanocomposite samples are summarized in Table 5. A common characteristic in all samples is the absence or considerable decrease of Ago peaks. The results confirm the redox reaction between AgNPs and Hg2+ from the solution. The amalgams that can be attributed to these peaks are moschellandsbergite (Ag2Hg3), mercury–silver alloy (Ag2Hg3) and luanheite (Ag3Hg). In addition, it is interesting to note the existence of Hg1+ (calomel, Hg2Cl2) and Ag2+ (AgO) on the surface, which indicates the gradual oxidation of Ago to higher oxidation states and the gradual reduction of Hg2+. The existence of residual Cl− on the surface is also confirmed by SEM-EDX (Table 3), leading to the formation of both Hg2Cl2 and AgCl. Finally, the formation of HgO shows that mercury can be bound on the surface as oxide. As is evident, differences in the identified peaks were found even for the same sample processed under the same conditions (0.3 mmol/g). This is a result of the very small amounts of formed compounds and thus, weak peaks. Obviously, the results are not conclusive, but they offer strong evidence of amalgam formation.

X-ray diffraction peaks of selected AgNPs@SiO2 samples after interaction with mercury and most probable identified compound(s) in order of probability

| 0.1 mmol/g Ag | 0.2 mmol/g Ag | 0.3 mmol/g Ag | 0.3 mmol/g Ag |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15.07 | 15.09 | 15.11 | - |

| AgO | AgO | AgO | |

| 21.96 | 22.42 | 22.31 | 21.9 |

| SiO2, Hg2Cl2 | SiO2 | SiO2 | SiO2, Hg 2 Cl 2 |

| - | - | - | 27.88 |

| AgCl | |||

| 30.49 | 30.46 | 30.56 | - |

| Ag2Hg3* | Ag2Hg3* | Ag2Hg3* | |

| 31.55 | 31.31 | - | - |

| Ag3Hg | Ag3Hg, Ag2Hg3, HgO | ||

| 32.26 | 32.27 | - | 32.08 |

| AgCl, Ag3Hg | AgCl, Ag3Hg | AgO | |

| - | - | 34.03 | - |

| AgO, HgO | |||

| - | - | - | 38.01 |

| Ag2Hg3, Ag o | |||

| - | - | - | 44.39 |

| Ag2Hg3, Ag o | |||

| - | - | 46.65 | 46.27 |

| AgCl, Ag 2 Hg 3 , Hg 2 Cl 2 | AgCl, Ag 2 Hg 3 , Hg 2 Cl 2 | ||

| - | - | - | 55.00 |

| Ag2Hg3, AgCl | |||

| - | - | - | 64.27 |

| Ag2Hg3, Ag o | |||

| - | - | - | 77.9 |

| Ag2Hg3, Ag o | |||

* This is a mercury–silver alloy different from the moschellandsbergite amalgam, which has the same chemical formula.

The SEM (Figure 11) and TEM (Figure 6) images clearly show that AgNPs@SiO2 interacts with mercury ions. These images show that the sample morphology changes dramatically; i.e., after interaction with mercury, the surface becomes heterogeneous, agglomerations form and nanoparticles disappear.

SEM image of 0.4 mmol/g AgNPs@SiO2 after interaction of mercury.

4. Conclusions

Biosourced silica was synthesized from RH and used as a substrate for the formation of silver nanocomposites with Ag contents of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mmol/g SiO2. The results demonstrated that the affinity of the AgNPs@SiO2 nanocomposites for mercury is high due to a combination of adsorption and silver–mercury and mercury chloride reactions. The XRD measurements indicate that chlorargyrite, calomel and amalgams are formed on the surface of the material. The stoichiometry of the amalgamation reaction seems to scale with the silver content, but no hyperstoichiometry was observed. The observation of amalgamation reaction and reactivity scaling are promising but not conclusive, and more detailed experiments and characterizations are required.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Nazarbayev University ORAU project Hyperstoichiometry Activity in Metal Nanoparticle Interaction (HYPER Activ), SOE 2015 009 (2015-2018) and partly funded by the Nazarbayev University ORAU project Noble metals nanocomposites hyper-activity in heterogeneous non-catalytic and catalytic reactions (HYPERMAT), SOE2019012 (2019-2021), Grant Number 110119FD4536.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0