1. Introduction

Due to the intrinsic properties of the fluorine atom, fluorinated compounds possess unique properties [1, 2, 3]. Consequently, fluorinated molecules play an important role in a wide range of applications, such as materials [4, 5, 6, 7, 8], battery technology [9, 10, 11], agrochemistry [12, 13, 14], medicinal chemistry [15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21], medical imaging [21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27] …. In order to develop new compounds with increasingly specific properties for targeted applications, the research of new fluorinated groups for the functionalization of various molecules has seen a growing interest in the last decade [28]. In this respect, the association of fluorinated moieties with heteroatoms has been particularly studied, with an important focus on chalcogens [29].

This interest in CF3O, CF3S and CF3Se moieties is due to their specific properties. Indeed, these substituents possess electronic properties that can modify the electron density of the molecules and thus some of their behaviors (Table 1) [30]. In addition, these groups possess a high lipophilicity, which will contribute to the improvement of the physicochemical properties of compounds, such as their membrane permeation to increase their bioavailability (Table 1) [31, 32, 33, 34]. Finally, some unusual conformational modifications can also be attributed to these moieties [35].

Hammett (σ), Swain–Lupton (F,R) electronic parameters and Hansch–Leo (πR) lipophilicity parameters

| Group | σm | σp | F | R | πR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CF3O | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.39 | −0.04 | 1.04 |

| CF3S | 0.40 | 0.50 | 0.36 | 0.14 | 1.44 |

| CF3Se | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.02 | 1.61 |

The chemistry of CF3O, CF3S and CF3Se groups is an old topic that has been studied since the 1960s. In 2010, the field received a new impetus, in particular with the development of new reagents that allow the direct introduction of CF3E (E = O, S, Se) groups onto molecules [29, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Based on our experience in this chemistry, our laboratory was one of the pioneering groups that, fifteen years ago, initiated a re-examination of the chemistry of CF3E moieties by developing new reagents to perform direct trifluoromethyl chalcogenations. In this account, we will give an overview of the reagents we have developed and summarize our contributions to the field.

2. Back to the beginning

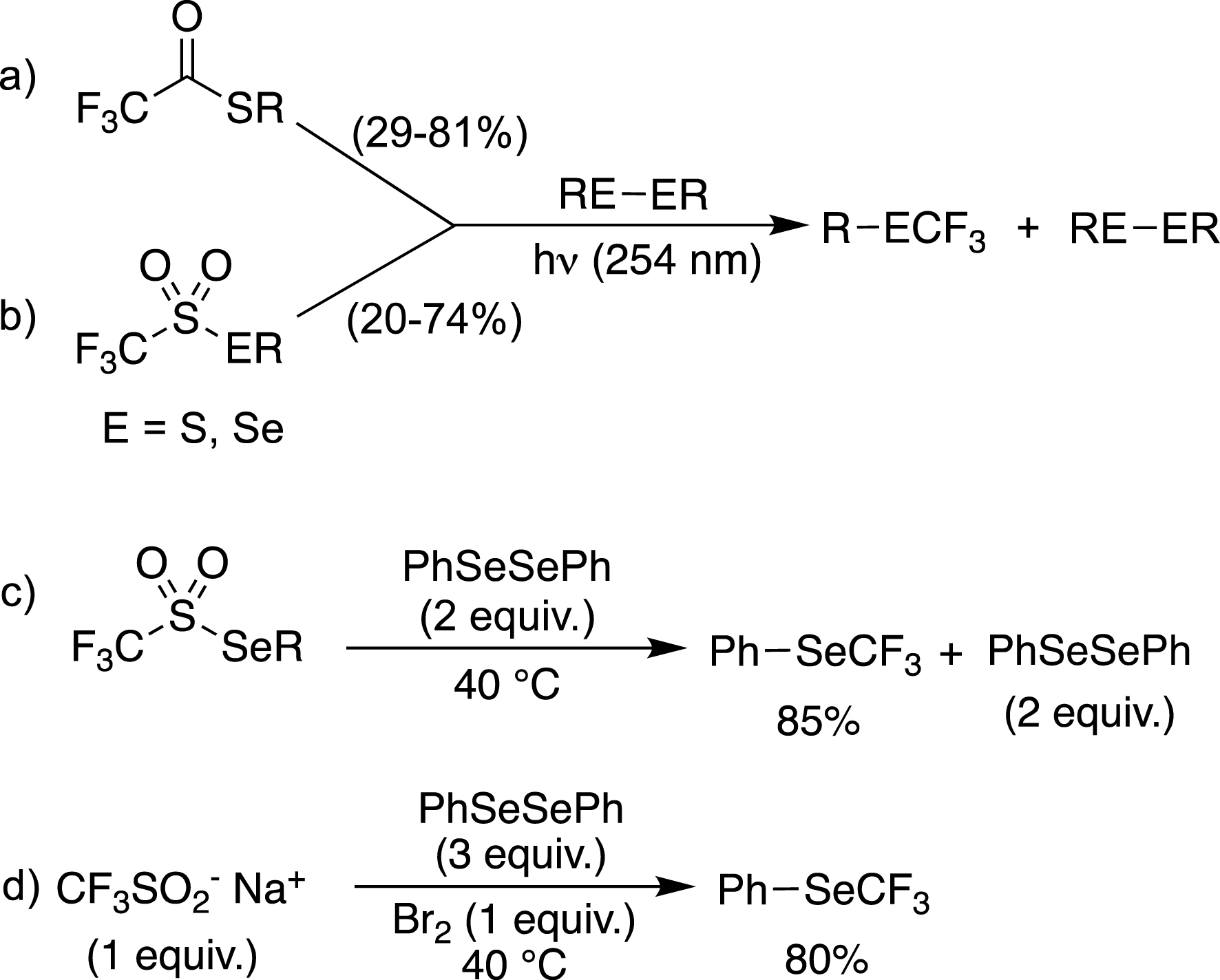

Our research interest in the trifluoromethylchalcogenyl groups began in the mid-1990s with the trifluoromethylation of sulfur and selenium derivatives. We initially developed radical trifluoromethylations of disulfides and diselenides using UV photolysis of trifluoromethyl thioesters (Scheme 1a) and trifluoromethanethio(seleno)sulfonates (Scheme 1b) [40]. In the case of trifluoromethaneselenosulfonates, similar results have been obtained by thermal activation (Scheme 1c) [41]. Since trifluoromethaneselenosulfonates were synthesized from Langlois’ reagent (CF3SO2Na) and diselenides, a one-pot process was also successfully carried out (Scheme 1d) [41].

Radical trifluoromethylation of disulfides and diselenides.

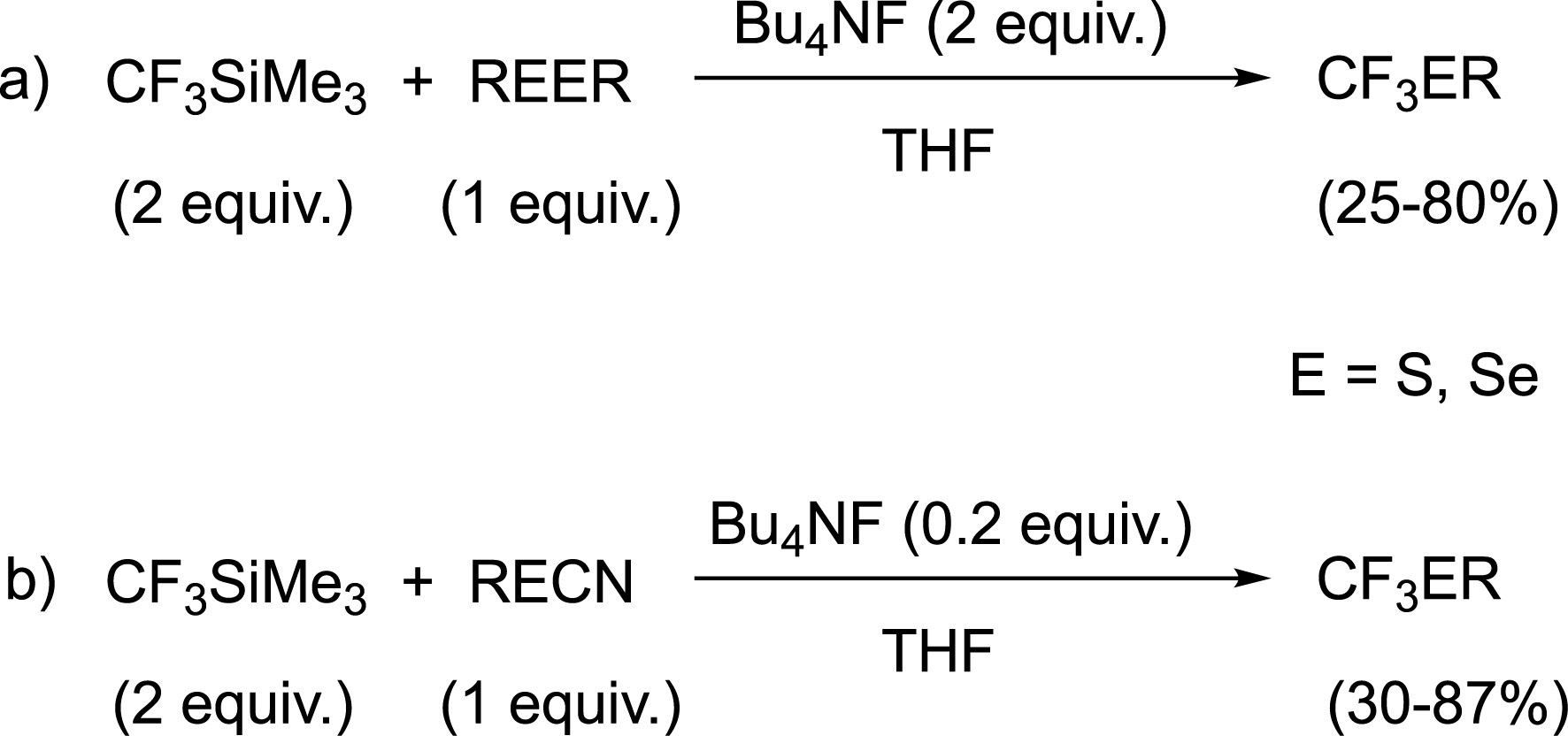

More interestingly, nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of disulfides and diselenides was subsequently developed by employing the commercially available Ruppert–Prakash reagent (CF3SiMe3) (Scheme 2a) [42]. However, disulfides and diselenides are often difficult to obtain as starting materials and only one part of the dichalcogenide is utilized. To circumvent these drawbacks, the more accessible thiocyanates and selenocyanates were considered as surrogates and provided to be highly valuable starting materials for the efficient synthesis of trifluoromethylsulfides and trifluoromethylselenides (Scheme 2b) [43].

Nucleophilic trifluoromethylation of dichalcogenides and chalcogenocyanates.

This last strategy remains a valuable tool in the synthesis of a wide range of compounds, as evidenced by its continued use in the literature [44, 45, 46, 47, 48]. It is also worth noting that the reaction has been extended to other fluorinated groups, starting from the corresponding silylated reagents (RFSiMe3) [45, 49, 50].

3. Direct trifluoromethylthiolation

Although the strategy developed previously using thiocyanates was effective, it required two steps, with the preliminary synthesis of the corresponding thiocyanate. In light of these considerations, we sought to explore a more elegant and intuitive approach from a retrosynthetic point of view: the direct trifluoromethylthiolation. At the beginning of this investigation, the subject was relatively understudied and essentially limited to nucleophilic reactions, with the particularly sensitive CF3S− anion [36, 51]. With regard to an electrophilic approach, the few results obtained were mainly with CF3SCl [36, 51], a highly toxic gas [52].

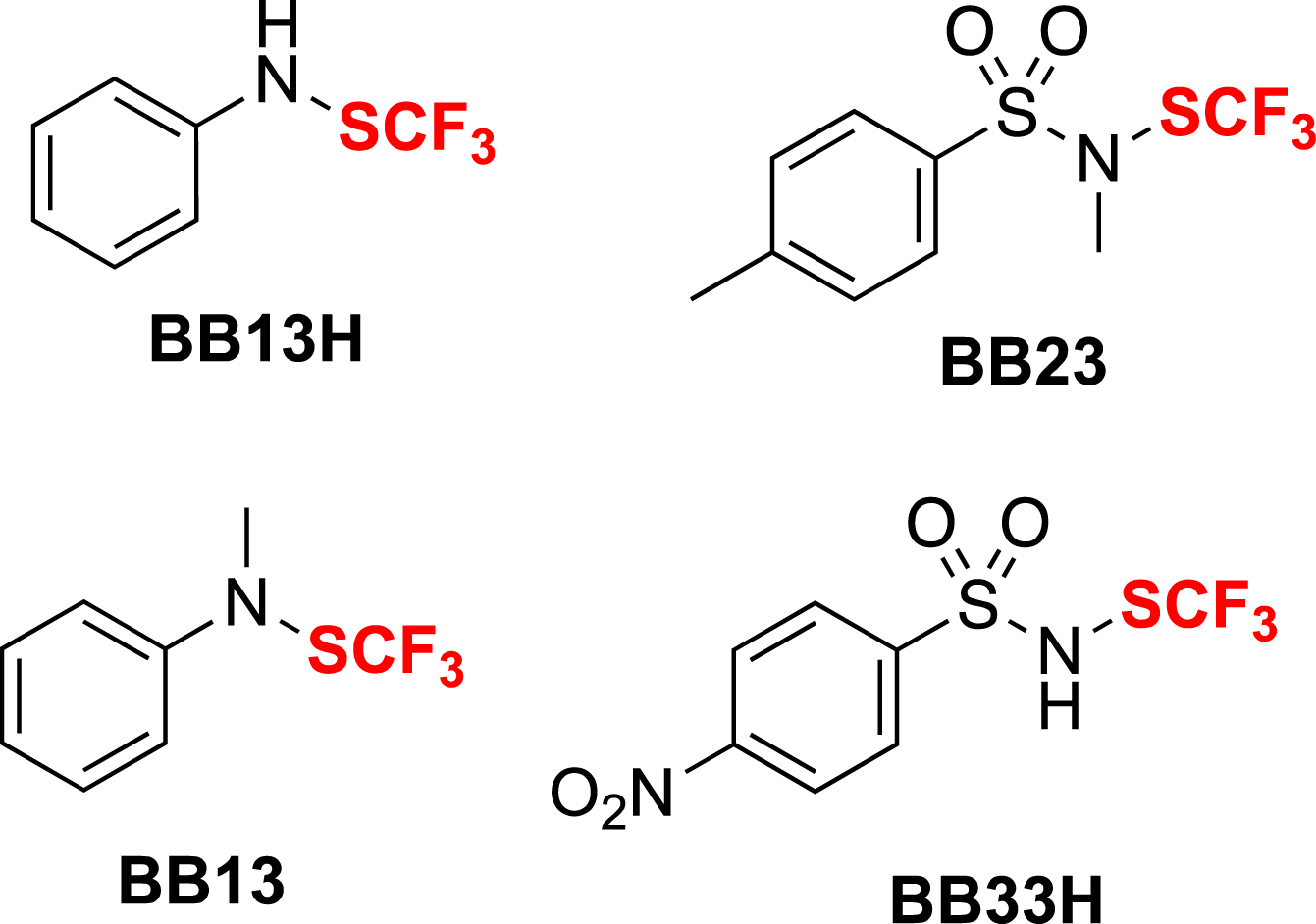

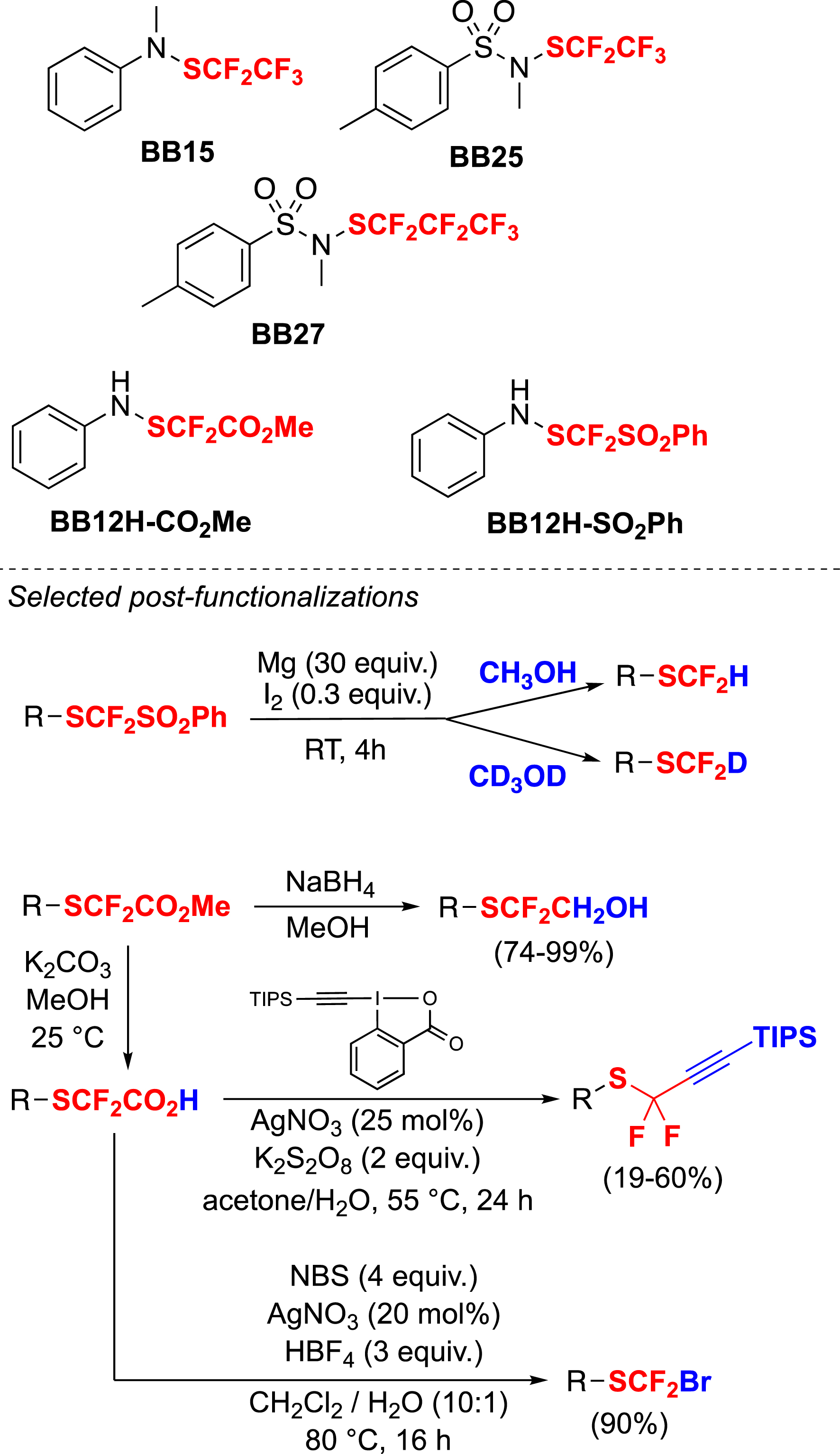

In order to propose a safer reagent, we focused our interest on trifluoromethanesulfenamides, which could be either liquid or solid and could behave as an electrophilic donor of the CF3S moiety due to the polarization of the S–N bond. This approach was inspired by our previous work on the synthesis of trifluoromethylsulfinamidines, where we had discovered their rearrangement under acidic conditions to trifluoromethanesulfenamides [53]. With the development of an efficient synthetic method, we have proceeded to the synthesis of several reagents for the electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolation reaction (Figure 1) [54].

Trifluoromethanesulfenamide reagents for electrophilic trifluorometylthiolation.

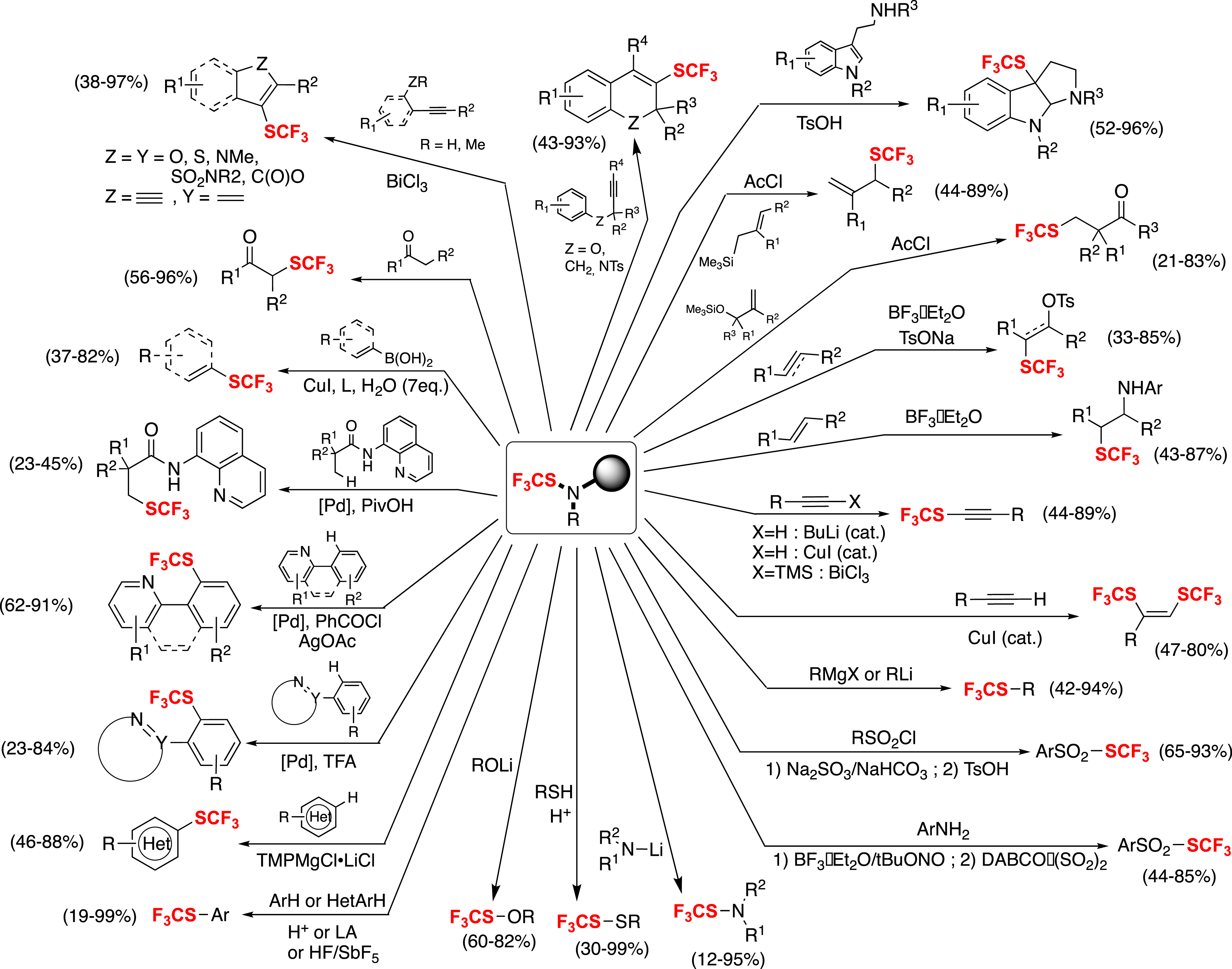

Reagents BB13 and BB23 are the most commonly used to perform various electrophilic trifluoromethyl thiolations. BB23 exhibits superior reactivity compared to BB13 [55], due to its higher electrophilicity [56]. They have been used in a variety of reactions to form C–SCF3 bonds (e.g., cross-coupling reactions, SEAr, electrophilic additions, reactions with organometallics). They have also been used with heteronucleophiles to form heteroatom–SCF3 bonds. These reagents have been used not only by our research group but also by other laboratories worldwide (Scheme 3) [29, 51, 57, 58, 59].

Direct electrophilic trifluoromethylthiolations with trifluoromethanesulfenamides.

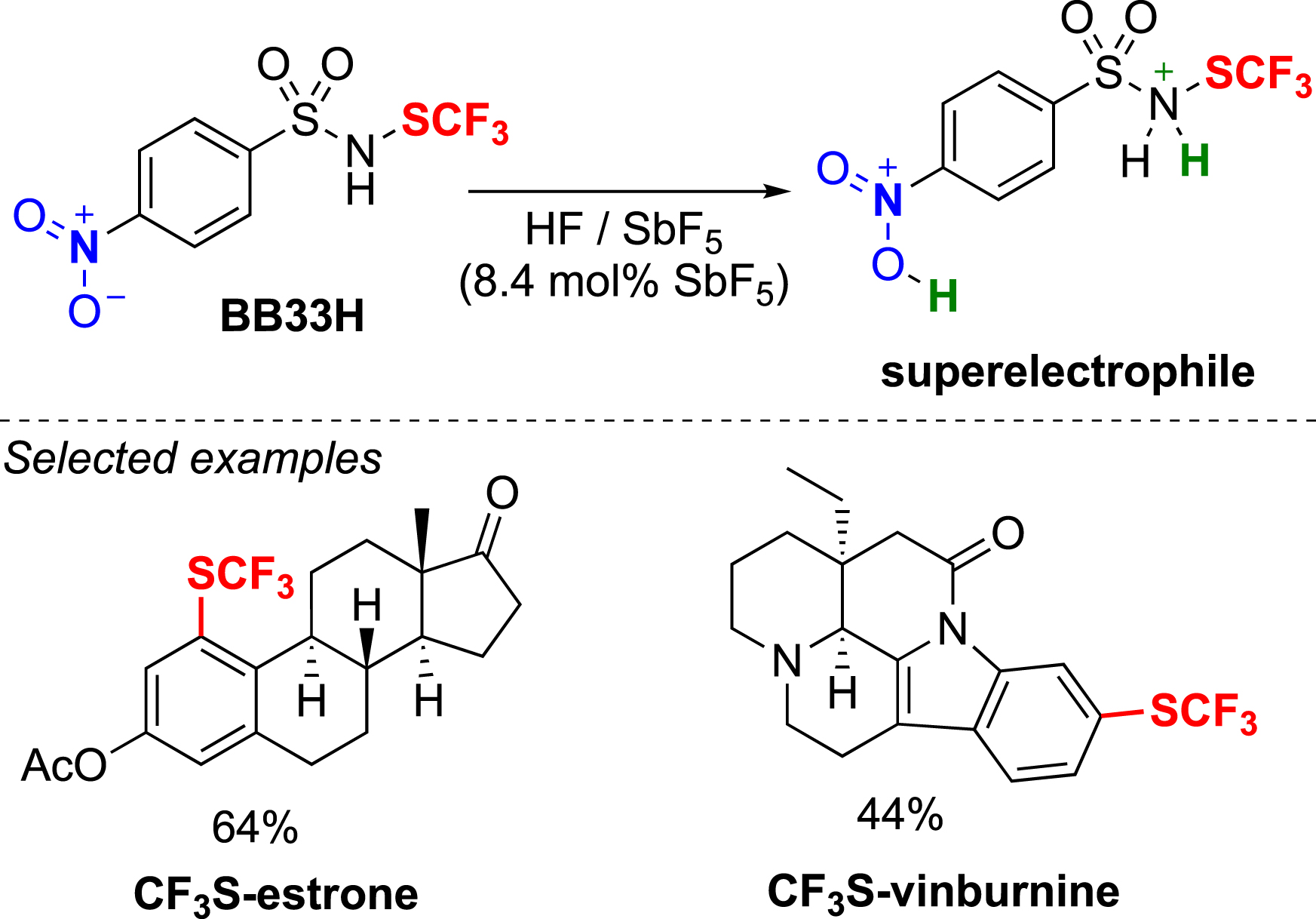

Reagent BB33H has been specifically designed for use in superacidic conditions to generate a superelectrophile. In collaboration with S. Thibaudeau, the trifluoromethylthiolation of some substrates that failed under standard conditions was successfully carried out under these conditions. This often resulted in unusual regioselectivity (Scheme 4) [60].

Trifluoromethylthiolation in superacid conditions.

Interestingly, BB23 can also be used in nucleophilic trifluoromethylthiolations through an Umpolung reactivity. In fact, BB23 reacts with Bu4NI to form the transient CF3SI species, which represents an inverse polarization of the S–I bond [61]. A second equivalent of Bu4NI can then attack the iodine atom to release the CF3S− anion, which can be involved in various nucleophilic reactions (Scheme 5) [62, 63, 64].

Umpolung reactivity of BB23.

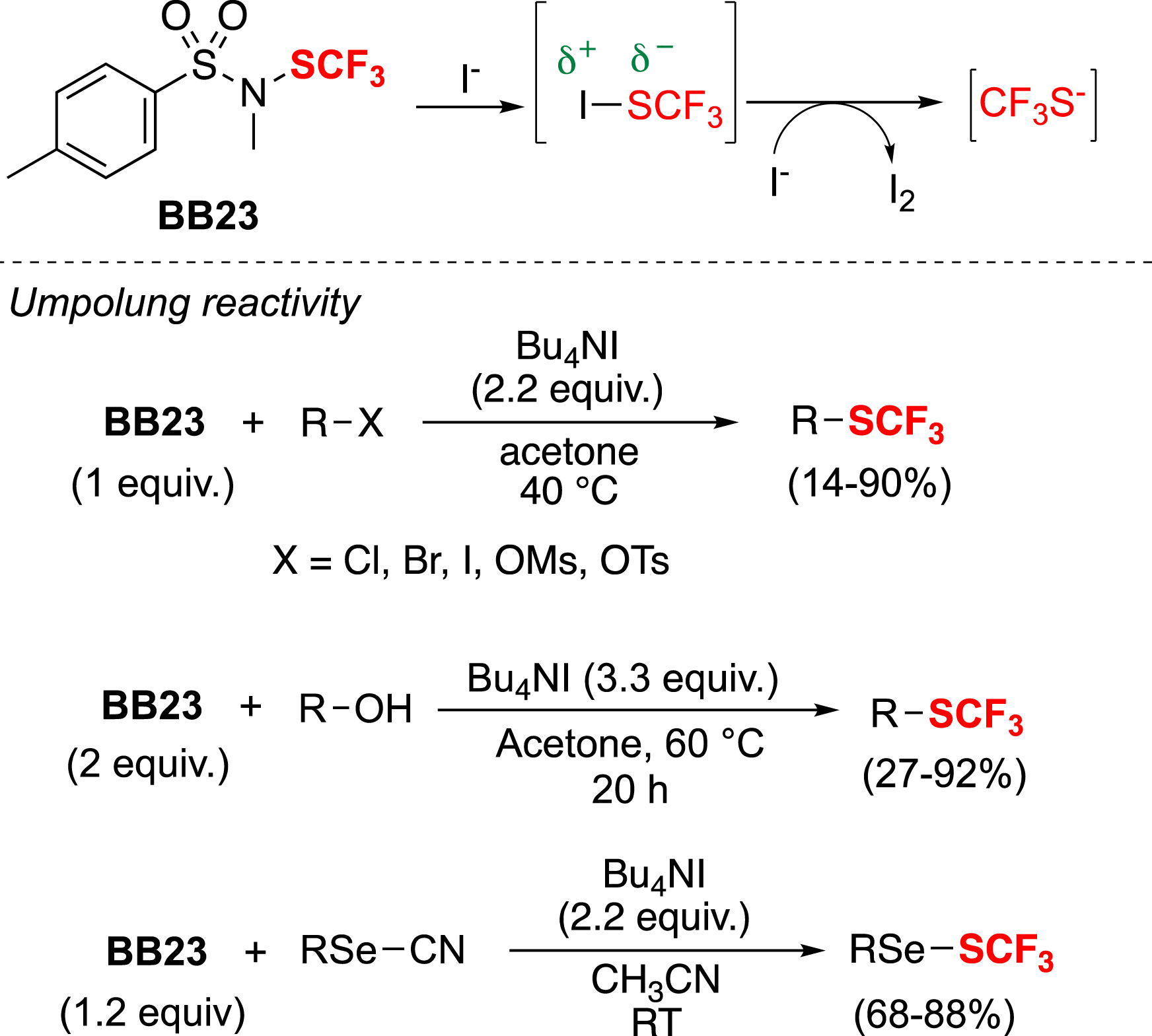

Finally, this family of reagents has been extended to include other fluorinated moieties. Consequently, a variety of reagents with similar reactivity have been developed to introduce different fluoroalkylthio groups onto organic substrates. The products obtained have undergone further post-functionalizations, using the SCF2CO2Me and SCF2SO2Ph moieties, to obtain molecules with other fluorinated moieties (Scheme 6) [65, 66].

Other reagents and post-functionalizations to obtain compounds with various fluorinated moieties.

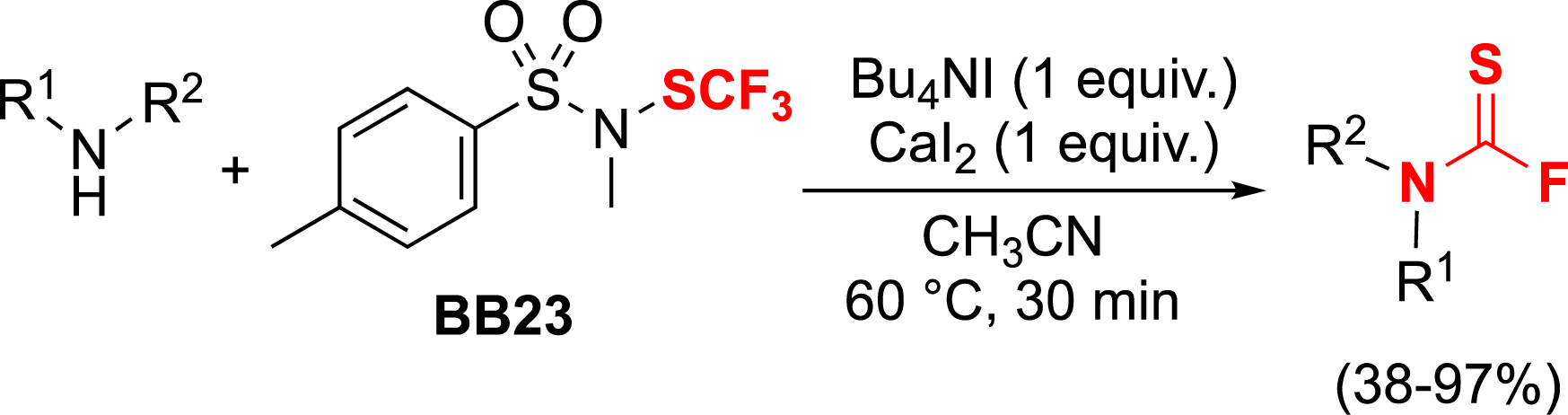

The CF3S− salts have been described in the literature as difluorothiophosgene generators [67, 68, 69, 70, 71]. Since BB23 can release this anion under iodide activation, we considered using the BB23 reagent to synthesize thiocarbamoyl fluorides. The reaction requires the presence of calcium salts, which facilitate the degradation of the trifluorothiomethanolate anion to difluorothiophosgene. This intermediate can then be reacted with amines to yield the expected thiocarbamoyl fluorides (Scheme 7) [72].

4. Direct trifluoromethylselenolation

In our ongoing investigation of the direct trifluoromethylchalcogenation reaction, we continued our chalcogen exploration by moving down the column to focus our attention on selenium.

Although selenium is toxic in high doses, it is also an essential trace element in human physiology [73, 74]. In addition, some trifluoromethylselenolated compounds have recently shown interesting properties as potential anticancer agents [47, 48].

At the beginning of this project, the chemistry of CF3Se was essentially limited to the use of the sensitive CF3Se− anion [29, 38, 75, 76]. However, the synthesis of this anion requires cumbersome conditions, starting with the use of toxic red selenium. The electrophilic CF3SeCl species has also been poorly described, but its inefficient and tedious synthesis [77] and its toxicity and volatility have severely limited its use [29, 38, 76].

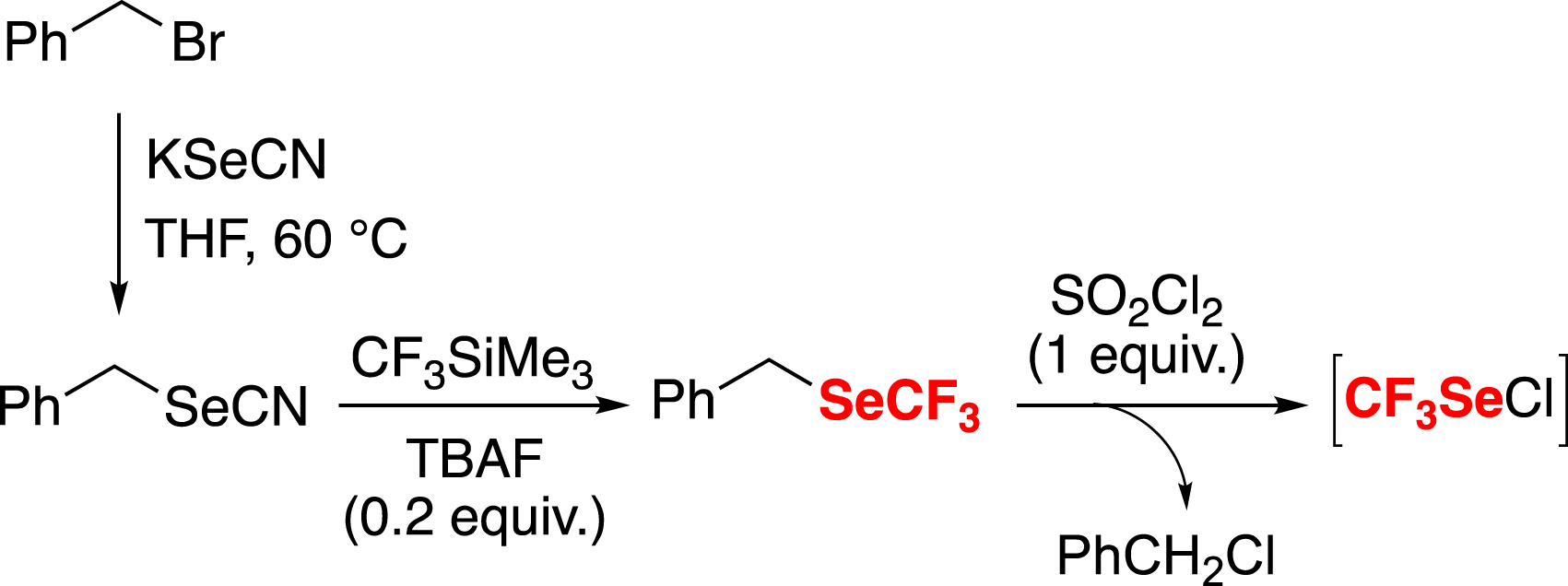

We decided to reinvestigate the chemistry of CF3SeCl, but under safe conditions, by generating it in situ with a quantitative reaction (Scheme 8) [49], inspired by the work of E. Magnier [78].

In situ generation of CF3SeCl from benzyl trifluoromethyl selenide.

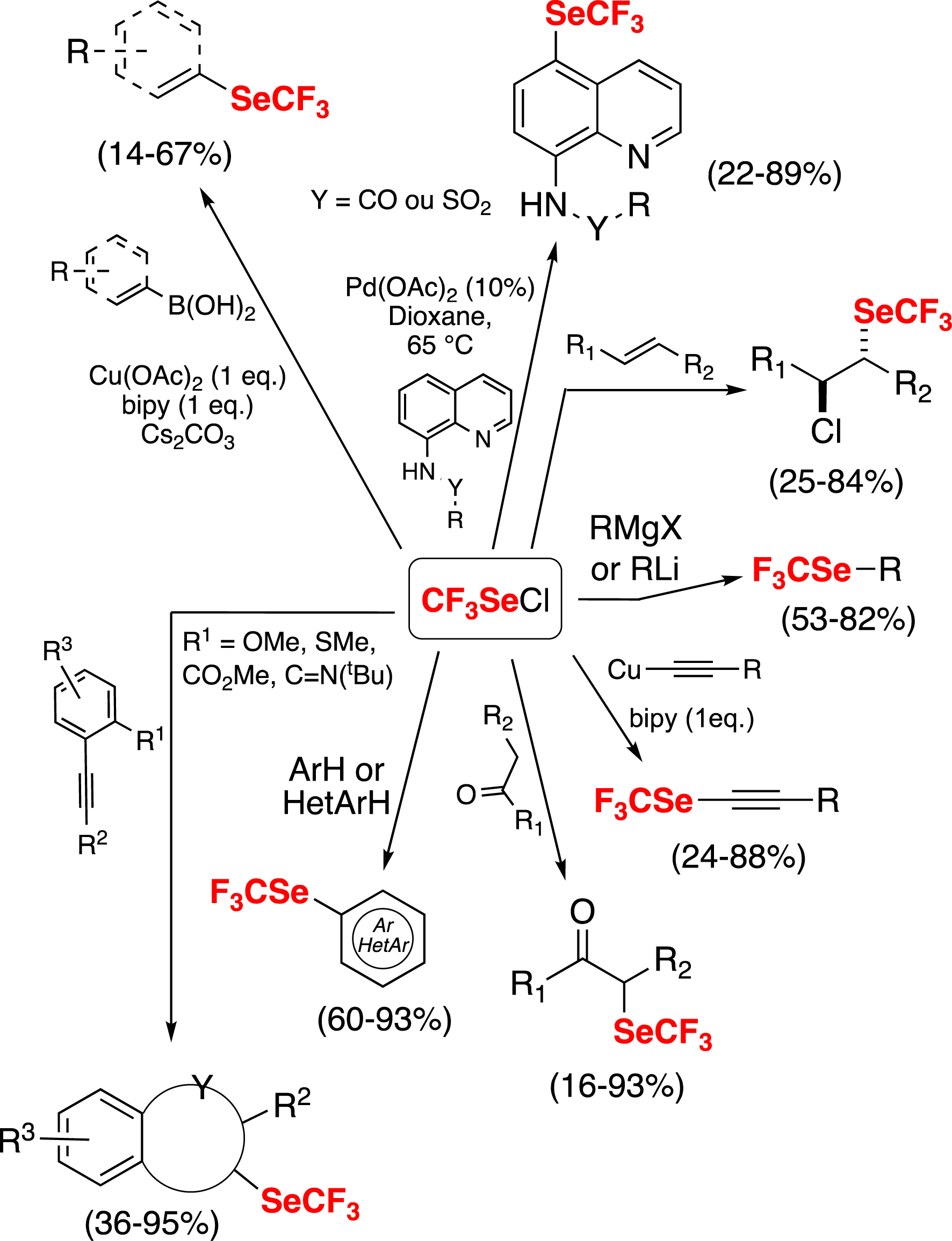

Thus, by using benzyl trifluoromethyl selenide, a readily accessible prereagent, we were able to perform a series of direct electrophilic trifluoromethylselenolations [29, 38, 76], by the in situ preparation of CF3SeCl (Scheme 9) [49].

Electrophilic trifluoromethylselenolations with CF3SeCl.

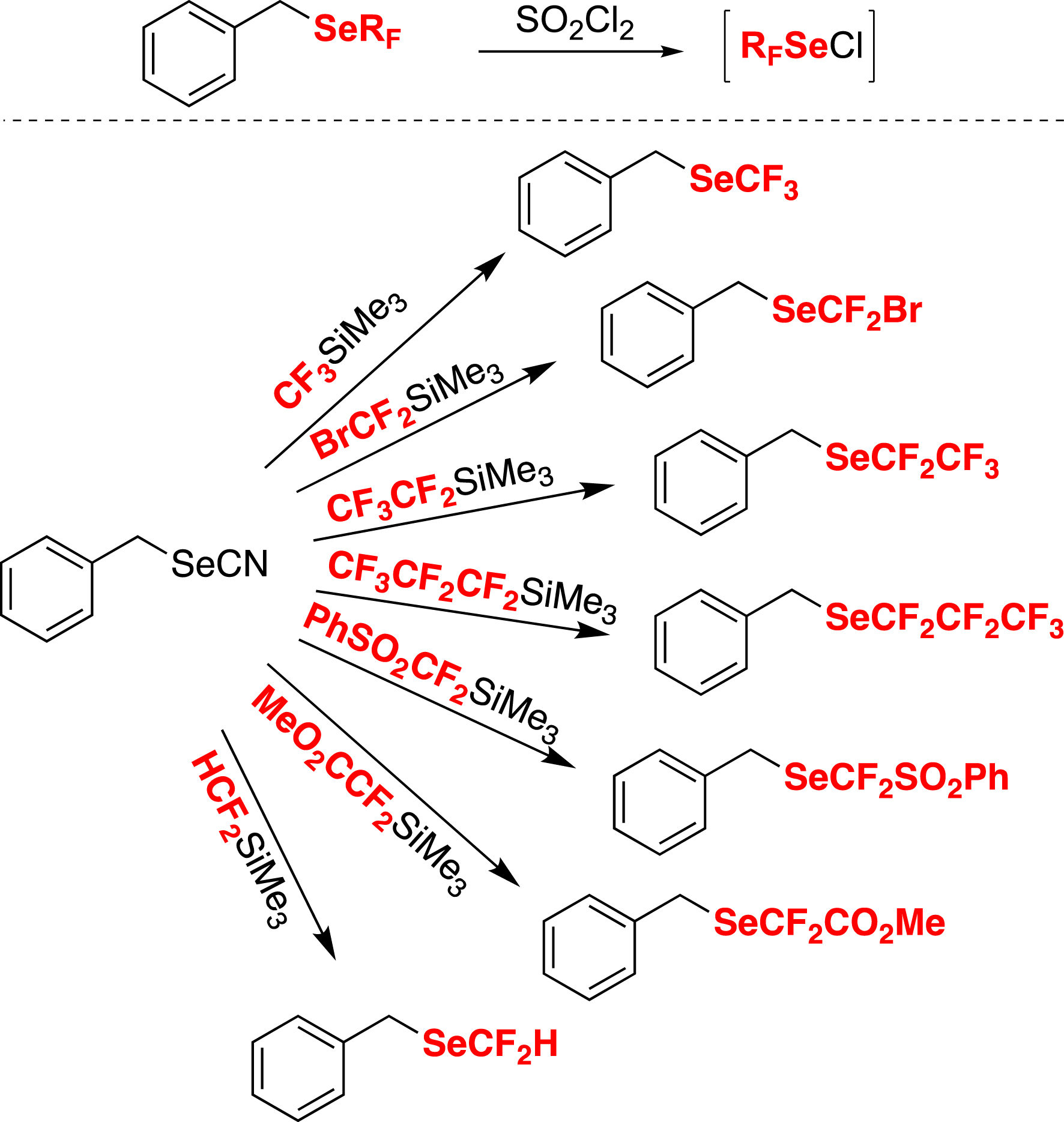

Notably, this method has been successfully extended to other fluorinated groups. This has been achieved by the synthesis of various benzyl fluoroalkyl selenides as prereagents, which generate RFSeCl species [49]. This has opened the way to various fluoroalkylselenolations (Scheme 10) [29, 38, 76].

Various prereagents for electrophilic fluoroalkylselenolations.

Despite the efficiency of this method, the main problem is the simultaneous production of an equivalent of benzyl chloride during the synthesis of CF3SeCl (Scheme 8). Consequently, this reactive species can interfere in some reactions with side reactions. This is well illustrated by the reactions with Grignard or lithium reagents, where two equivalents of organometallic species were required to achieve satisfactory yields [79].

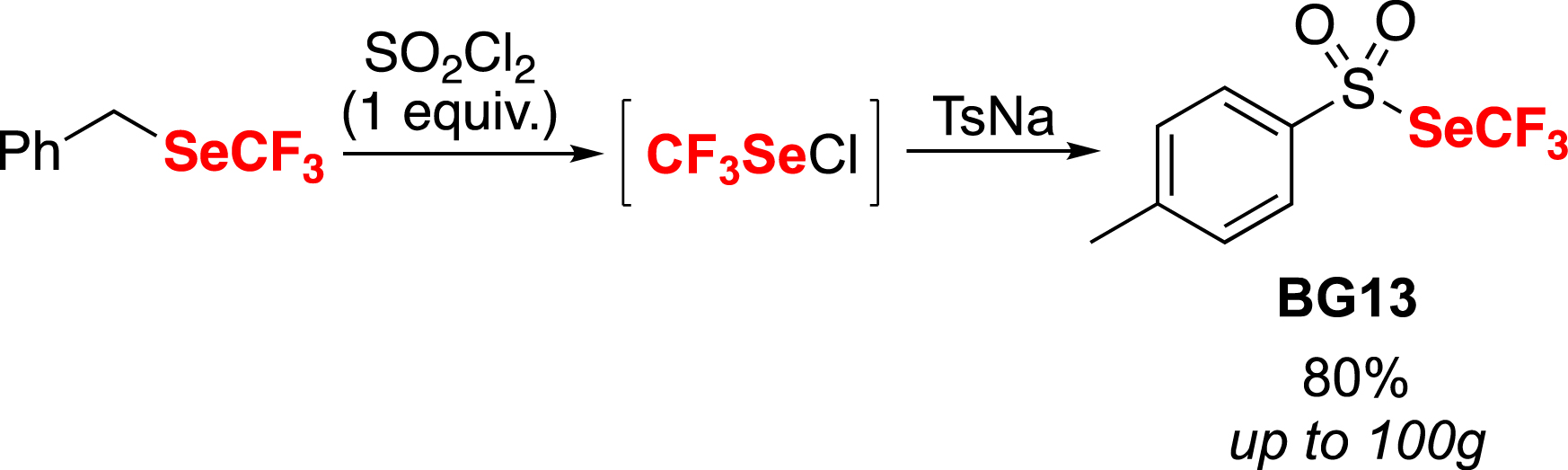

To overcome this drawback, a new reagent was designed that was isolatable, stable, non-volatile and easy to handle. Building upon our previous experience in the chemistry of selenosulfonates [80], we decided to capture the CF3SeCl with a sulfinate salt to form a trifluoromethyl selenosulfonate [81]. Consequently, the trifluoromethyl toluene selenosulfonate BG13 was successfully obtained in good yield using the sodium toluene sulfinate salt (Scheme 11). This liquid compound showed stability, purifiability on silica gel, and non-volatility [81].

Synthesis of the trifluoromethyl toluene selenosulfonate BG13.

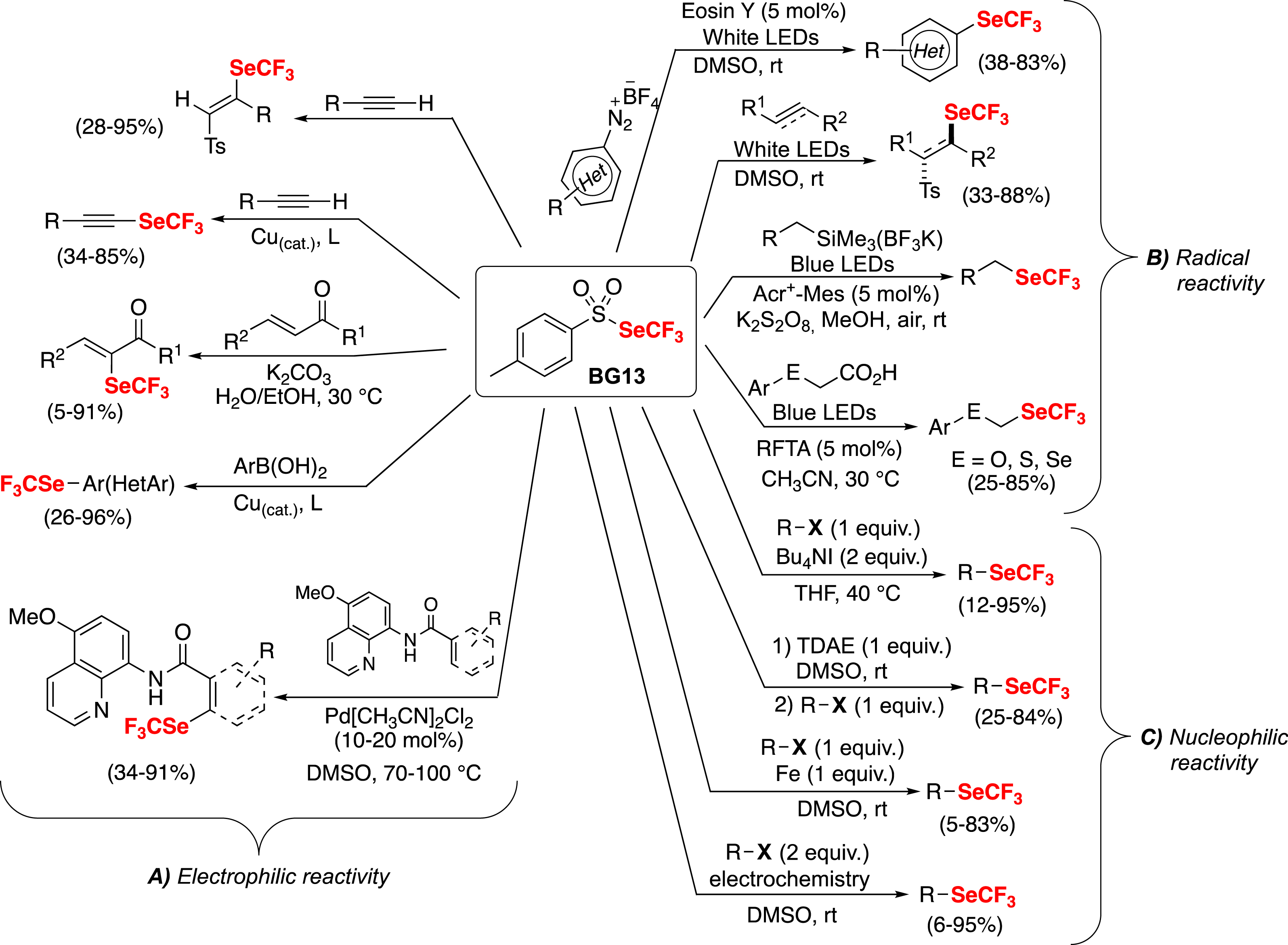

This new reagent has shown remarkable efficacy in facilitating trifluoromethylselenolations (Scheme 12A) [39], including cross-coupling reactions [81] and aromatic and vinylic C–H functionalizations [82, 83].

Reactivity of the trifluoromethyl toluene selenosulfonate BG13.

The homolytically cleavable SO2–Se bond allows the BG13 reagent to participate in radical reactions under photocatalytic or photolytic conditions (Scheme 12B) [32, 39, 84, 85]. In collaboration with the group of E. Magnier, we were able to design new fluorinated groups, namely (trifluoromethylselenyl)methylchalcogenyl (CF3SeCH2E, E = O, S, Se), which have a high lipophilicity parameter (Hansch–Leo lipophilicity parameter up to 2.24) [32].

Building on the Umpolung reactivity of the trifluoromethyl thiolating reagent BB23 (Scheme 5), we also succeeded in performing nucleophilic trifluoromethyl selenolation in the presence of Bu4NI (Scheme 12C) [86]. Interestingly, similar nucleophilic reactivity has also been observed under reductive conditions (Scheme 12C) by using organic reducer (TDAE) [87], metallic reducer (Fe) [88] or electrochemistry [89].

In conclusion, this trifluoromethyl toluene selenosulfonate reagent (BG13) proved to be a versatile reagent capable of performing electrophilic, nucleophilic or radical reactions, depending on the conditions.

In addition, more highly fluorinated homologues of BG13 have been developed with similar reactivity to give fluoroalkylselenolated compounds [39].

5. Direct trifluoromethoxylation

After our previous successful experiences with CF3S and CF3Se chemistry, we decided to move up the chalcogen column to tackle the very challenging CF3O chemistry. Although trifluoromethoxylated compounds are in high demand, particularly in medicinal chemistry [90], direct trifluoromethoxylation reactions are still underdeveloped [29, 37, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95]. In addition, the majority of the reagents are often sophisticated and require the use of expensive and multistep synthesis.

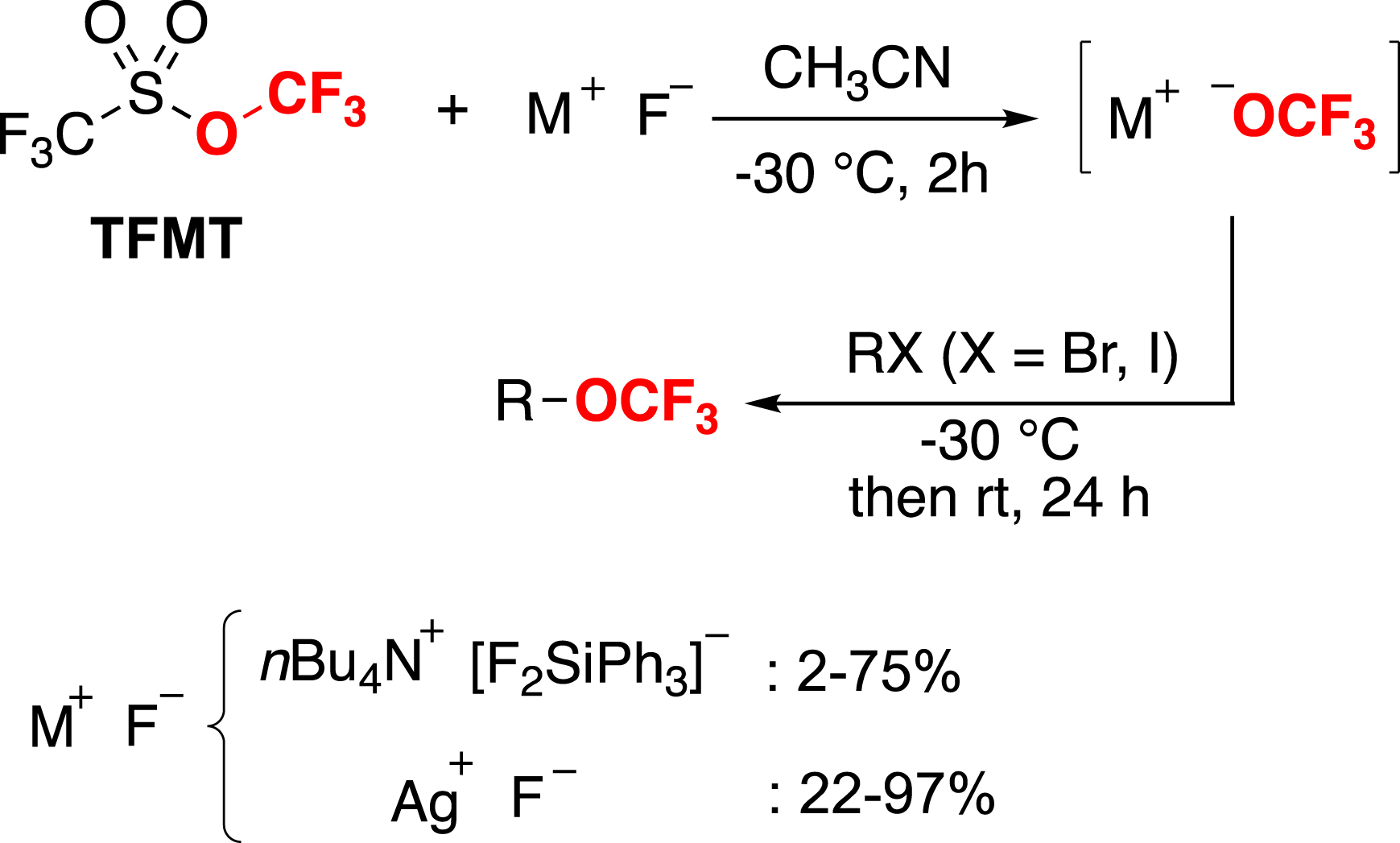

We decided to focus our efforts on the nucleophilic trifluoromethoxylation. The main challenge associated with this approach is the instability of the CF3O− anion, which quickly collapses to difluorophosgene by expelling a fluoride anion. To overcome this drawback, we initially considered using the commercially available trifluoromethyl triflate (TFMT) to generate the CF3O− anion in situ [96]. In the presence of fluoride anion, TFMT releases the CF3O− anion, which can then be captured by an electrophile to perform nucleophilic substitutions (Scheme 13) [97].

Nucleophilic trifluoromethoxylation with TFMT.

Although this strategy has yielded promising results, TFMT is an expensive reagent and is highly volatile, making it difficult to handle. In addition, the better yields are generally obtained with a stoichiometric amount of silver fluoride (AgF).

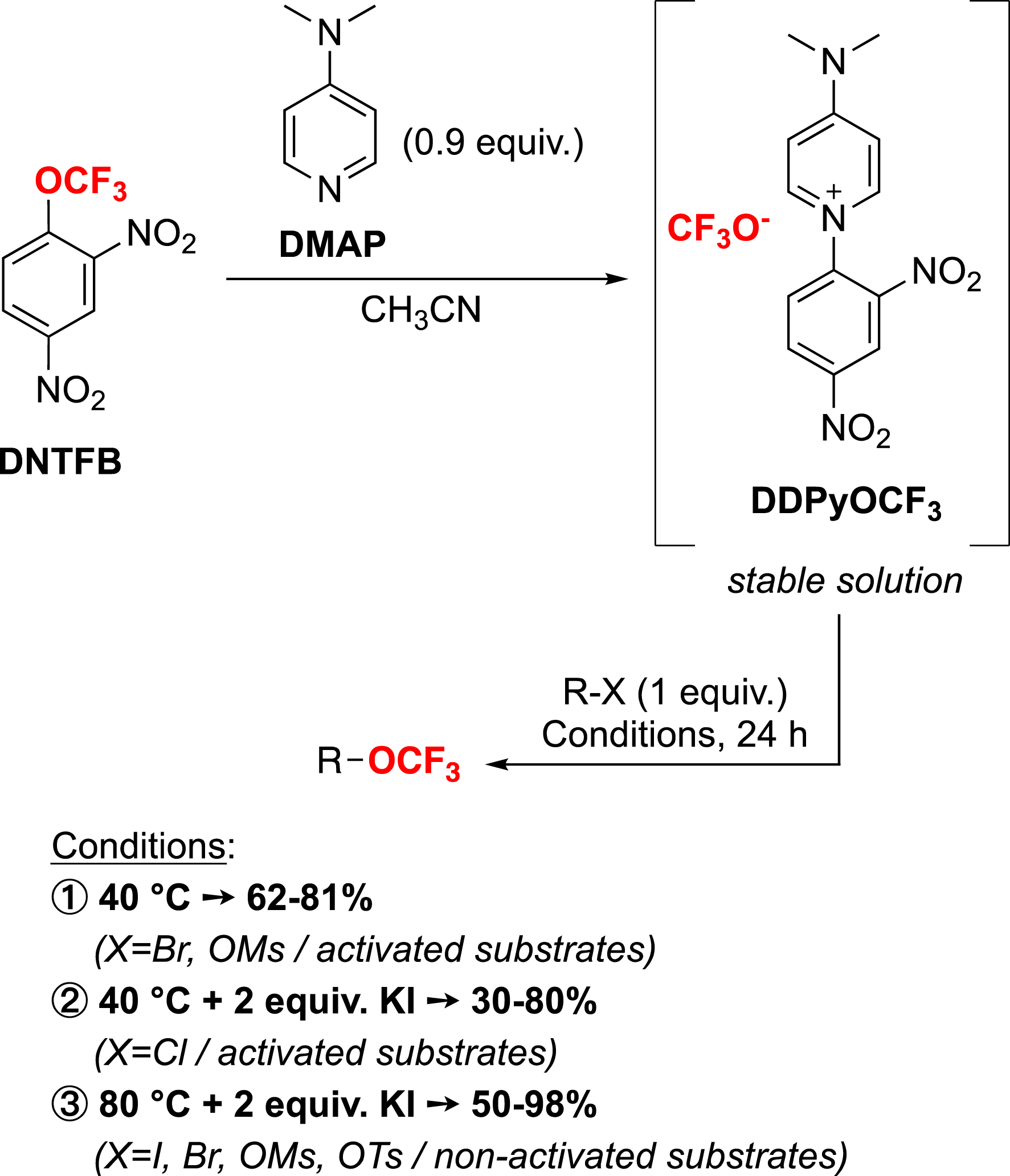

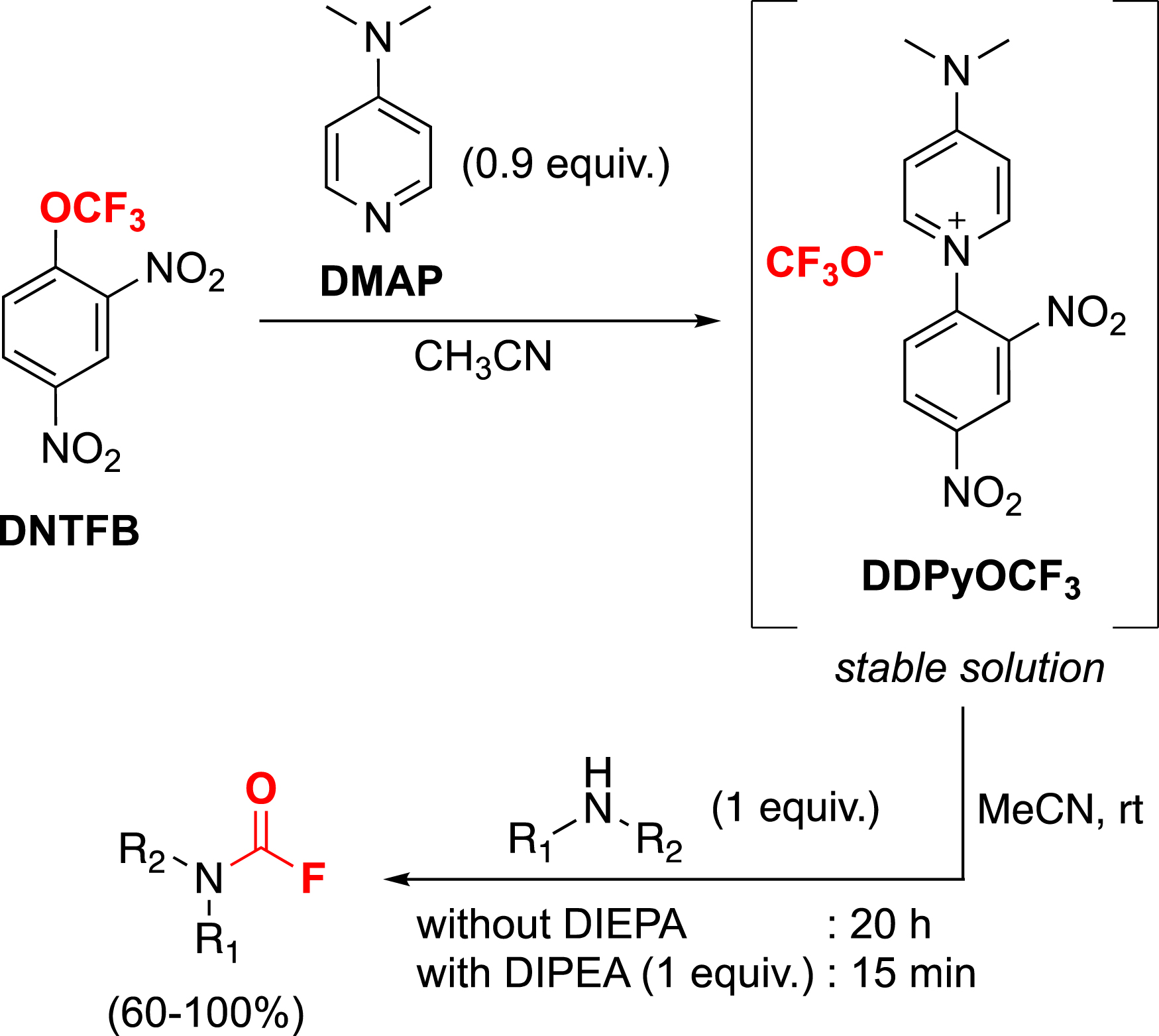

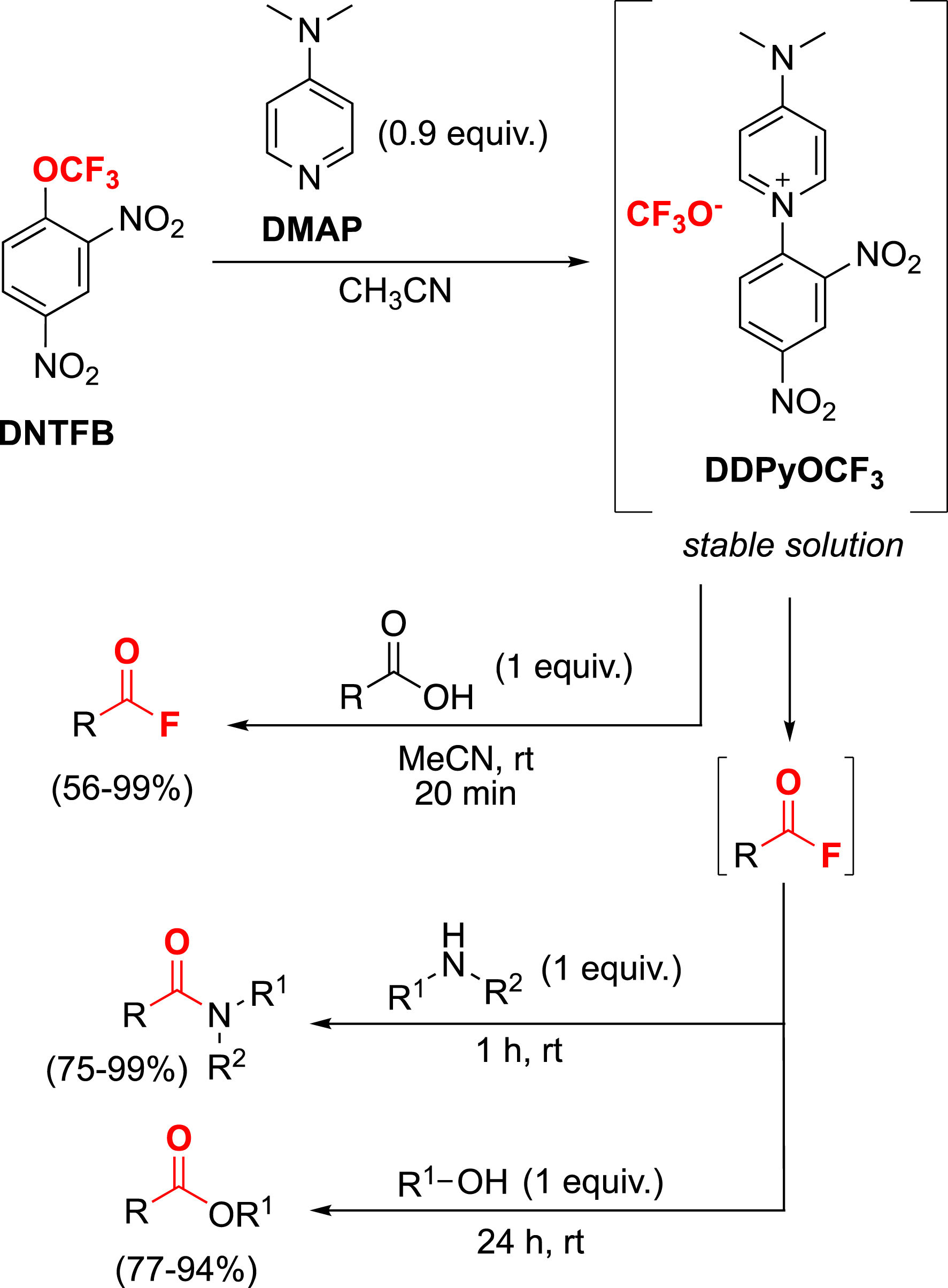

To propose an alternative reagent that is inexpensive, non-volatile and reactive in metal-free conditions, we investigated the use of 2,4-dinitro-trifluoromethoxybenzene (DNTFB). A SNAr process allows DNTFB to generate a trifluoromethoxide anion upon reaction with DMAP (Scheme 14) [98]. Surprisingly, this salt (DDPyOCF3) was found to be stable in solution (up to 6 weeks).

Nucleophilic trifluoromethoxylation with DDPyOCF3 arising from DNTFB.

With this stable salt, in collaboration with the group of F. Leroux, nucleophilic substitutive trifluoromethoxylations could be carried out under mild and metal-free conditions with good yields and over a wide range of substrates (Scheme 14). Furthermore, a rational guideline for the reaction conditions depending on the starting compounds was proposed [99].

Although the DDPyOCF3 salt is stable, it remains sensitive in the presence of a hydrogen bond donor to then generate difluorophosgene. We took advantage of this collapse to propose an efficient synthesis of carbamoyl fluorides by simply mixing amines with DDPyOCF3 (Scheme 15) [100]. Thanks to this work, an in-depth study of carbamoyl fluorides has also been realized. We have demonstrated the remarkable stability of these compounds in aqueous solutions up to pH 10 and good stability in conditions that mimic the physiological environment. Finally, an isotopic exchange with fluorine-18 opens the way to the potential use of [18F]carbamoyl fluorides as a label in PET imaging [100].

Synthesis of carbamoyl fluorides with DDPyOCF3.

This ability to generate the difluorophosgene in situ under safe conditions has also been applied to the synthesis of acid fluorides (Scheme 16). The strategy has been extended to a one-pot process to directly obtain amides or esters by converting DDPyOCF3 as a potential coupling reagent [101].

Synthesis of acyl fluorides, amides or esters with DDPyOCF3.

6. Conclusion

In summary, over the past 15 years, we have developed several efficient reagents to perform trifluoromethoxylations, trifluoromethylthiolations and trifluoromethylselenolations of a wide range of substrates under a variety of conditions. The adventure continues as we continue to explore the versatility of these reagents to propose more efficient tools for the organic chemist’s toolbox.

Declaration of interests

The author does not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and has declared no affiliations other than his research institution.

Funding

The CNRS, the French Ministry of Education and Research and CPE Lyon are thanked for their financial support.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges all the students and collaborators who have contributed to these works. A special warm thanks to F. Leroux and E. Magnier for the strong and friendly collaboration we pursue from year to year. The French Fluorine Network (GIS-FLUOR) is also warmly thanked for its unconditional support.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0