1 Introduction

The characteristic spectroscopic feature of rare-earth ions in glass is the inhomogeneous broadening resulting from the distribution of the crystal fields at the variety of rare-earth-ion sites in the amorphous solid 〚1〛. Several laser spectroscopic techniques, such as fluorescence line narrowing (FLN), spectral hole burning, etc., 〚2, 3〛 are required to obtain a detailed information about the local field, and ion–ion and ion–host interaction processes. When the activator ion concentration in glass becomes high enough, ions interact and ion–ion energy transfer occurs. Due to the inherent disorder of glass, ions in nearby sites may be in physically different environments with greatly varying spectroscopic properties. Therefore, in addition to causing a spatial migration of energy, the transfer may also produce spectral diffusion within the inhomogeneously broadened spectral profile 〚2〛. The migration of the electron excitation over the inhomogeneous profile (spectral migration) determines the effectiveness of the generation (amplification) of the stimulated emission 〚1〛. One of the kinetic methods of migration investigation consists in analysing time-resolved luminescence spectra after selective excitation 〚1, 3–7〛. The time-resolved fluorescence line narrowing (TRFLN) technique provides us with a way of measuring optical energy propagation from the initially excited subset of ions to other elements of the inhomogeneously broadened line. Previous works 〚1, 4, 5〛 on Nd-doped glasses utilised a non-resonant pumping scheme to excite the 4F3/2 state, which is responsible for the principal Nd3+ fluorescence. Under the non-resonant pumping condition, the ‘accidental coincidence’ effect influences the originating state of the fluorescence in a complicated way and hence no direct analysis can be made of the TRFLN donor–donor dynamics in such cases 〚7〛. The introduction of tuneable lasers for resonant excitation in the near-infrared made it possible to perform measurements on TRFLN under resonant excitation of the 4F3/2 state of Nd3+ in order to study the structure of inhomogeneously-broadened bands and migration of excitation energy among Nd3+ ions 〚3, 8, 9〛. It is worthwhile mentioning that TRFLN techniques have only been used in a few studies on spectral diffusion among Nd3+ ions in glasses 〚1, 3–5, 9〛; among these, there are only a few works performed in a resonant pumping scheme 〚3, 8–11〛 to excite the 4F3/2 state of Nd3+ ions.

This paper deals with the spectral migration of energy among Nd3+ ions in fluoroarsenate glasses. Recently, new glasses were discovered in the Na4As2O7, BaF2, YF3 system, which are parent materials with fluorophosphates glasses of the NaPO3, BaF2, YF3 system. As in the case of fluorophosphate glasses, large amounts of active rare-earth ions can be incorporated in replacement of yttrium. Whereas optical properties of some active ions have already been investigated in fluorophosphate glasses 〚12–14〛, the behaviour of rare-earth ions in fluoroarsenate glasses is practically unknown. In a previous work, we have characterised the optical properties of Nd3+ ions in these glasses 〚15〛. In this work, we investigate the existence of energy transfer among Nd3+ ions in fluoroarsenate glasses of the Na4As2O7, BaF2, YF3 system with different Nd3+ concentrations (0.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mol%) by using TRFLN spectroscopy and observing the emission characteristics of the system as a function of time, concentration, and excitation wavelength.

2 Experimental techniques

The fluoroarsenate glasses used in this work were prepared at the ‘Laboratoire de verres et céramiques’ of the University of Rennes (France). Glasses were synthesised in the (Na4As2O7–BaF2–YF3) ternary system and doped with 0.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mol% of NdF3.

The sample temperature was varied between 4.2 and 300 K in a continuous flow cryostat. Time-resolved resonant fluorescence line-narrowed emission measurements were obtained by exciting the samples with a Ti–sapphire laser, pumped by a pulsed frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser (9 ns pulse width), and detecting the emission with a Hamamatsu R5108 photomultiplier provided with a gating circuit designed to enable gate control from an external applied TTL level control signal. Data were processed by an EGG–PAR boxcar integrator.

3 Results and discussion

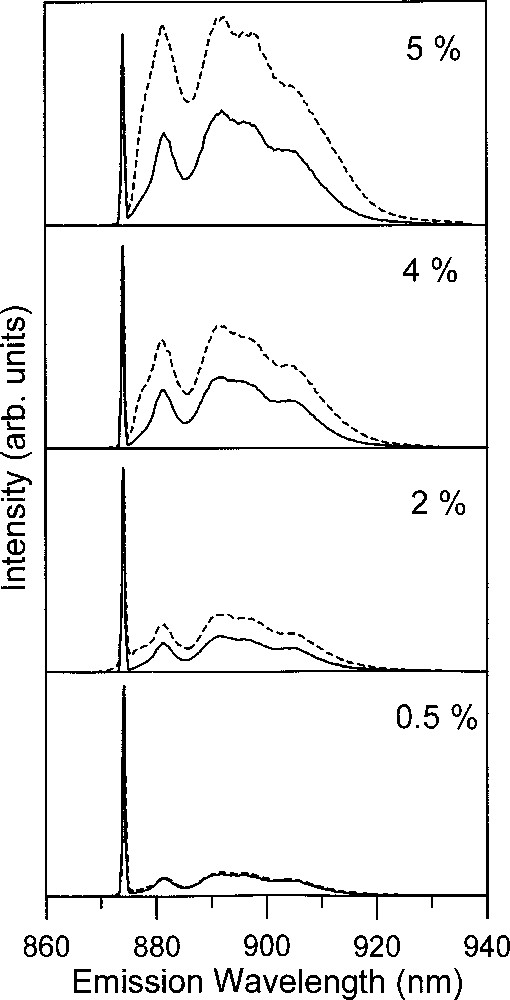

We have investigated the existence of energy transfer among Nd3+ ions in this glass by using TRFLN spectroscopy and observing the emission characteristics of the system as a function of time, concentration, and excitation wavelength. TRFLN spectra for the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition were performed for all concentrations at 4.2 K by using different resonant excitation wavelengths in the low energy Stark component of the 4I9/2→4F3/2 absorption band at different time delays after the laser pulse. Typical results from these measurements are given in Fig. 1, which shows the normalized 4F3/2→4I9/2 spectra at 4.2 K for the four concentrations 0.5, 2, 4, and 5 mol% of Nd3+ ions obtained at two different time delays after the laser pulse, 1 and 700 μs, by exciting at 874 nm. Two contributing components can be observed in the spectra. The one observed on the high-energy side of the line is a simple FLN line (linewidth ≈ 8 cm–1) corresponding to the emission to the lowest component of the 4I9/2 multiplet, which is the ground state of the ion. The position of this narrow line is essentially determined by the wavelength of the pumping radiation. The broad emission arises from the non-narrowed inhomogeneous line. As time delay increases, the relative intensity of the narrow line and the broad (non selected) emission changes, and the later becomes stronger, which indicates the existence of energy transfer between discrete regions of the inhomogeneous broadened profile. This effect increases with concentration. As can be observed, when Nd3+ concentration increases the broad non-selected emission becomes important. At higher concentrations, the transfer process appears at shorter time delays, but in all cases energy transfer produces a relative increase of the broad emission with respect to the narrow band.

Time-resolved fluorescence line-narrowed spectra of the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition obtained at 1 μs (solid line) and 700 μs (dashed line) after the laser pulse by excitation at 874 nm for the samples doped with 0.5, 2, 4, and 5 mol%. Measurements correspond to 4.2 K.

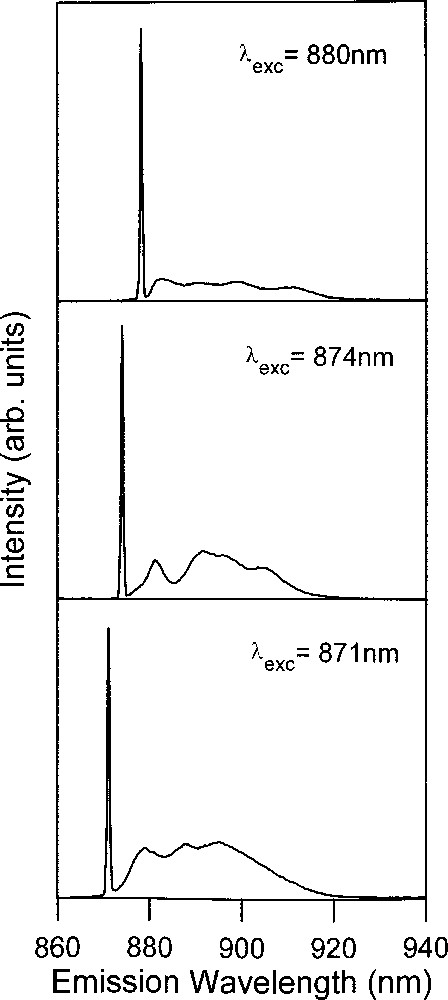

The 4F3/2→4I9/2 emission spectra performed by exciting at different wavelengths along the low energy Stark component of the 4I9/2→4F3/2 absorption band show that the broad emission decreases as the excitation energy decreases, which indicates that excitation energy can migrate mainly in one direction. As an example, Fig. 2 shows the TRFLN spectra for the sample doped with 2 mol% of Nd3+ obtained at three different excitation wavelengths. The same behaviour is observed in all samples.

Time-resolved fluorescence line-narrowed spectra of the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition obtained at 1 μs after the laser pulse by excitation at three different wavelengths for the sample doped with 2 mol%. Measurements correspond to 4.2 K.

The time evolution of laser-induced resonant line-narrowed fluorescence is produced by a combination of radiative decay and non-radiative transfer to other nearby ions. Subsequent fluorescence from the acceptors ions replicate the inhomogeneously broadened equilibrium emission profile, showing that transfer occurs not to resonant sites but to the full range of sites within the inhomogeneous profile. In this case, a quantitative measure of the transfer is provided by the ratio of the intensity in the narrow line to the total intensity of the fluorescence in the inhomogeneous band. Neglecting the dispersion in the radiative decay rate, and using the Föster formula for dipole–dipole energy transfer, one can write for the relationship between the integral intensities of the broad background emission IB and the narrow luminescence component IN 〚6〛:

The macroscopic parameter γ(EL) has the meaning of an integral characteristic, which reflects the average rate of excitation transfer from donors to the ensemble of spectrally non-equivalent acceptors 〚6〛.

This analysis deals with migration-induced changes in an individual luminescence band originating from transitions between a pair of Stark sublevels 〚6〛. However, in the case of Nd3+ ions, the luminescence spectra represent a superposition of different Stark components. At low temperature, where only the lowest Stark sublevels of the ground and metastable states are populated, the spectra show a narrow resonant Stark component and some broad emission due to transitions to the other Stark components of the ground state, whereas, at higher temperatures, the spectral pattern becomes more complicated. As a consequence, though at high temperatures spectral migration can be experimentally observed, the analysis in terms of equation (1), which considers a two-level scheme, becomes more complicated.

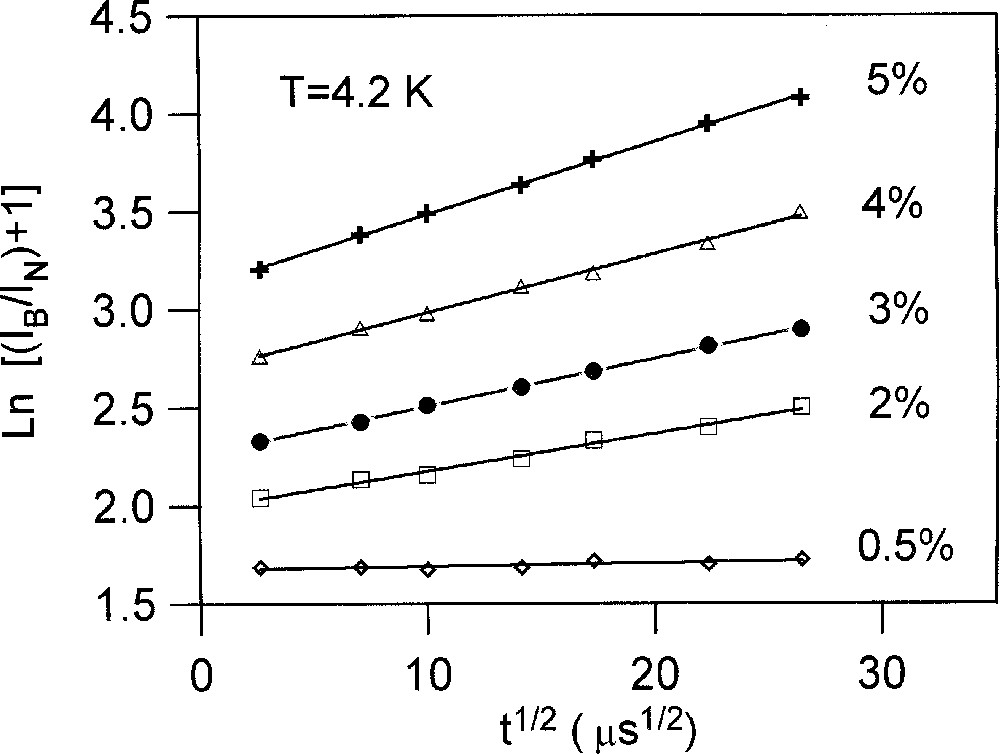

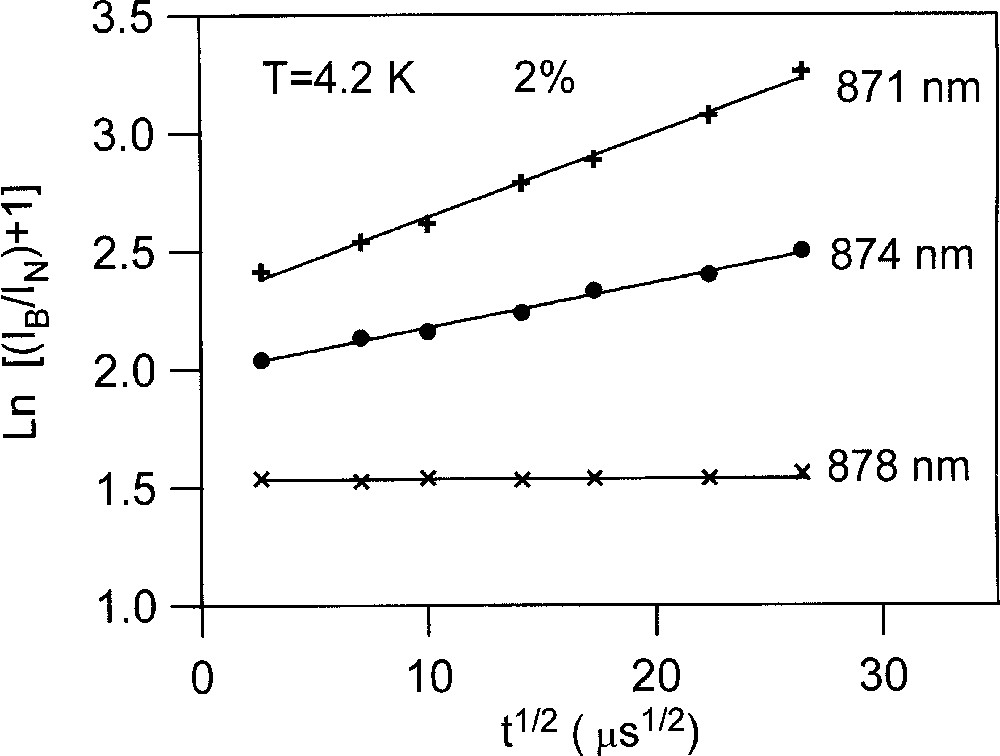

We have analysed the TRFLN spectra of the 4F3/2→4I9/2 transition obtained at different time delays between 1 and 700 μs according to equation (1) at 4.2 K. As an example, Fig. 3 shows the results for all samples for an excitation wavelength of 874 nm. As can be observed, a linear dependence of the ln〚(IB/IN) + 1〛 function on t1/2 was found, which indicates that a dipole–dipole interaction mechanism among the Nd3+ ions dominates in this time regime. The values of the average transfer rate indicate that energy transfer among Nd3+ ions is weak at concentrations up to 2 mol% at low temperature, and increases with increasing concentration. The γ values for this excitation wavelength were found to be 1.7, 19, 24, 30, and 37 s–1/2 for the samples doped with 0.5, 2, 3, 4, and 5 mol% respectively. The analysis of the TRFLN spectra obtained under excitation at longer wavelengths along the low energy Stark component of the 4I9/2→4F3/2 absorption band shows that the transfer rate depends on the excitation energy. As an example, Fig. 4 shows the analysis of the TRFLN spectra for the sample doped with 2 mol% of Nd3+ at three different excitation energies. As can be observed the value of the average transfer rate increases from 0.2 s–1/2 to 36 s–1/2 when the excitation energy increases from 11 389.5 cm–1 (878 nm) to 11 481.05 cm–1 (871). This rise in the energy migration rate is due to the increasing number of possible acceptors.

Analysis of the time evolution of the TRFLN 4F3/2→4I9/2 emission by means of equation (1) for all samples. Symbols correspond to experimental data and the solid line fits equation (1). Data correspond to 4.2 K.

Analysis of the time evolution of the TRFLN 4F3/2→4I9/2 emission by means of equation (1) for the sample doped with 2 mol% of Nd3+ for three different excitation wavelengths. Symbols correspond to experimental data and the solid line fits equation (1). Data correspond to 4.2 K.

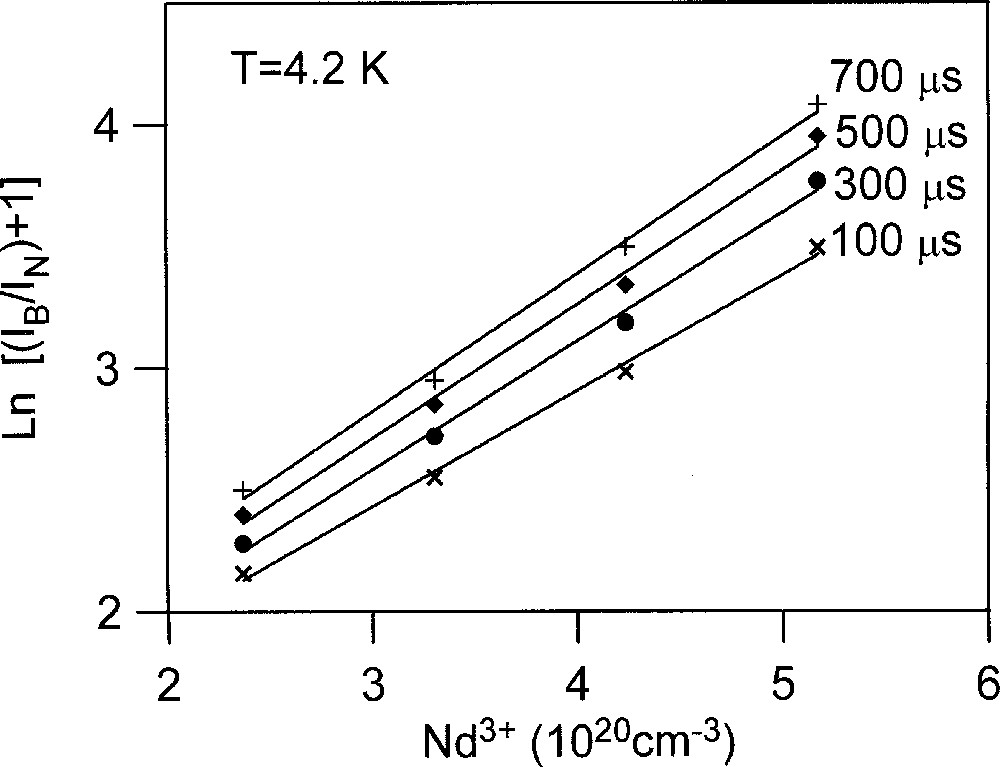

The concentration dependence of the spectral migration rate can be obtained from the luminescence spectra of different concentration samples with the same time delay after laser excitation. The increase of the intensity of the broad band relative to that of the narrow component shows the concentration induced growth of the migration transfer rate. Fig. 5 shows the concentration dependence of ln〚(IB/IN) + 1〛 obtained at 4.2 K at 100, 300, 500, and 700 μs after the laser pulse. The observed linear behaviour is again consistent with a dipole–dipole energy transfer mechanism.

Concentration dependence of the quantity ln〚(IB/IN) + 1〛 for Nd3+ ions. Symbols correspond to experimental data and the solid line is a linear fit. Data were obtained at different time delays after the laser pulse by exciting at 874 nm.

4 Conclusions

Resonant time-resolved fluorescence line-narrowing spectroscopy shows the existence of energy migration between discrete regions of the inhomogeneous broadened 4F3/2 spectral profile. The analysis of the 4F3/2→4I9/2 emission spectra obtained at low temperature as a function of time, concentration, and excitation wavelength shows that the electronic mechanism responsible for the Nd3+–Nd3+ interaction can be interpreted in terms of a dipole-dipole energy transfer.

The average energy transfer rate found in these fluoroarsenate glasses is a 40% lower than the one found in oxide glasses 〚11〛 for the same concentration of Nd3+ ions.

Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the Basque Country University (Ref.: UPV13525/2001), the Basque Country Government (Ref.: PI1999-95), and the Spanish Government (Ref.: BFM2000-0352).