1 Introduction

Cyclosiloxanes with organic groups attached to the silicon atoms may serve as starting materials for linear polysiloxanes using an opening reaction of the SinOn rings [1]. These materials, known as silicones, have a wide range of applications in industry. The substituents at silicon besides the chain lengths determine the physical and chemical properties of silicones [2]. We were interested to synthesise by a versatile step-by-step route SinOn cycles with inorganic substituents at silicon presenting different centres of reactivity to facilitate an exchange with other chemical groups. In contrast to a considerable number of reports on cyclosiloxanes with organic groups, such inorganic representatives are rare [3–5].

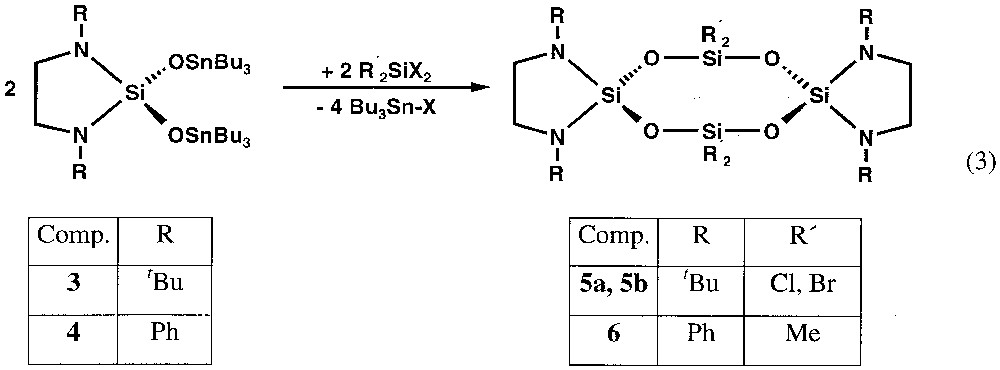

We have recently described the selective syntheses of amino- and chloro-substituted cyclotrisiloxanes [6–8]. These six-membered ring compounds are obtained either by salt elimination reactions [6] or by ClSnR3 elimination between dichlorodiaminosilanes and hexaorganostannoxane [7, 8]. The transfer of this approach to eight-membered Si4O4 rings with different substituents on the silicon atoms is discussed in this paper.

2 Experimental

2.1 Methods and materials

Preparation and handling of the compounds described below was performed under exclusion of air and moisture in a nitrogen atmosphere. All solvents were dried with the appropriate drying agents and distilled prior to use. Elemental analyses (C, H, N) were performed on a LECO CHN 900 Elemental Analyzer. The NMR (1H, 13C, and 29Si) spectra were recorded on Bruker AC-200 and AM-400 spectrometers and referenced relative to TMS. Samples were run at room temperatures using C6D6 as lock solvent. The educts 1 [9], 2 [9] and hexabutyldistannoxane [10] were prepared according to published procedures.

2.2 Syntheses

2.2.1 [(CH2)2N2(tBu)2]Si(OSnBu3)2 (3)

To 3,5 g (13.0 mmol) [CH2-N(tBu)]2SiCl2(1) 13.24 ml (26.0 mmol) hexabutyldistannoxane was added in pure form. The liquid reaction mixture was stirred and heated up to 180 °C for 12 h. Even longer heating does not alter the equilibrium between the educts and products that is reached at this stage. The unreacted starting compounds as well as chlorotributylstannane formed as a by-product are removed by distillation at 10–3 atm. The product 3 is found in the residue and can be used without further purification, or can be distilled at 220 °C/10–3 atm using a column. Yield 9.01 g (60%) as viscous colourless liquid. (Found: C, 50.65; H, 9.24; N, 3.20. Calc. for C34H76N2O2SiSn2: C, 50.39; H, 9.45; N, 3.46%). 1H NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 0.88–1.65 (m, 54 H, SnBu3), 1.31 (s, 18 H, N t Bu) and 5.62 (s, 4 H, (CH2)2. 13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 14.0 (s, 6 C, Sn(CH2)3 C H3), 16.0 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 27.8 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 28.6 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 31.2 (s, 6 C, C(C H3)3), 42.3 (s, 4 C, (CH2)2) and 50.8 (s, 2 C, C (CH3)3). 29Si NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) – 56.6.

2.2.2 [(CH2)2N2(Ph)2]Si(OSnBu3)2 (4)

To 3.5 g (11.32 mmol) [CH2–N(Ph)]2SiCl2(2) 11.53 ml (22.64 mmol) hexabutyldistannoxane was added under strong stirring, the resulting liquid showing an increase in temperature. Stirring was continued for 60 min, followed by distillation at 80 °C of the formed chlorotributylstannane under reduced pressure (10–3 atm). The residue is pure compound 4, which is obtained as an oily clear liquid (yield 9.61 g (99%)). (Found: C, 53.60; H, 8.48; N, 3.05. Calc. for C38H68N2O2SiSn2: C, 53.67; H, 8.06; N, 3.29%). 1H NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 0.81–1.48 (m, 54 H, SnBu3), 3.30 (s, 4 H, (CH2)2) and 6.78–7.34 (m, 20H, Haromat). 13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 13.9 (s, 6 C, Sn(CH2)3 C H3), 16.1 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 27.6 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 27.9 (s, 6 C, Sn(C H2)3CH3), 42.7 (s, 2 C, (CH2)2), 114.9 (s, 4C, Cortho), 117.5 (s, 2C, Cpara), 129.2 (s, 4C, Cmeta) and 148.6 (s, 2C, Cipso). 29Si NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) – 62.3.

2.2.3 Syntheses of 5a, 5b and 6

To a solution of 8.95 g (11.02 mmol) 3 or 7.24 g (11.02 mmol) 4 in 25 ml diethylether, the equimolar amount of the respective SiX4 [X = Cl (1.26 ml), Br (1.37 ml), see below] or dimethyldichlorsilane (1.33 ml) is added dropwise. After a few minutes, the white solids 5a or 5b begin to precipitate. Stirring is continued for 5 h. In the case of compound 6, the solution is stirred for 12 h. The precipitate is separated from the solution by filtration, is washed with small amounts of cold diethylether and finally dried under reduced pressure to give a white powder.

2.2.3.1 {[(CH2)2N2(tBu)2]SiO(Cl)2SiO}2 (5a); {[(CH2)2N2(tBu)2]SiO(Br)2SiO}2 (5b)

5a: Yield 1.63 g (45%) white powder, m.p. 215 °C (dec.). (Found: C, 36.29; H, 6.45; N, 8.10. Calc. for C20H44Cl4N4O4Si4: C, 36.47; H, 6.73; N, 8.51%). 1H NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 1.09 (s, 36 H, C(C H3)3) and 2.84 (s, 8 H, (C H2)2). 13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 29.1 (s, 12 C, C(C H3)3), 41.1 (s, 4 C, (C H2)2) and 50.9 (s, 4 C, C (CH3)3). 5b: Yield 1.84 g (40%) white powder of m.p. 240 °C (dec.) (Found: C, 25.81; H, 5.35; N, 6.03%. Calc. for C20H44Br4N4O4Si4: C, 28.72; H, 5.30; N, 6.69%). 1H NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 1.11 (s, 36 H, C(CH3)3) and 2.86 (s, 8 H, (CH2)2). 13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 29.3 (s, 12 C, C(C H3)3), 41.2 (s, 4 C, (C H2)2) and 51.1 (s, 4 C, C (CH3)3). The poor solubility of 5a and 5b hampered the registration of the 29Si-NMR spectra.

2.2.3.2 {[(CH2)2N2Ph2]SiO(Me)2SiO}2 (6)

Yield 3.04 g (42%) white powder of m.p. > 280 °C. (Found: C, 58.28; H, 6.00; N, 8.33. Calc. for C32H40N4O4Si4: C, 58.49; H, 6.14; N, 8.53%). 1H NMR (THF): δ (ppm) –0.51 (s, 12 H, Si(CH3)2), 2.91 (s, 8 H, (CH2)2) and 6.40–6.97 (m, 20 H, Haromat); 13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 0.04 (s, 4 C, Si(CH3)2), 42.4 (s, 4 C (CH2)2); 115.1 (s, 4C, Cortho), 118.5 (s, 2C, Cpara), 129.2 (s, 4C, Cmeta) and 146.7 (s, 2C, Cipso). Because of its poor solubility, the 29Si-NMR spectrum of 6 could not be obtained.

2.2.4 [(Me)2SiO(Cl)2SiO]2 (7)

To a solution of 0.845 g (1.29 mmol) 6 in 30 ml THF 14.0 ml of a solution of HCl in THF (0.654 molar) is slowly added dropwise. The hydrochloride precipitate is separated from the solution by filtration. After removing all volatiles under reduced pressure, 7 can be sublimed from the brown oily residue. Yield 0.09 g (18%) colourless crystals of m.p. 35 °C. (Found: C, 12.56; H, 3.05%. Calc. for C4H12Cl4O4Si4: C, 12.70; H, 3.20%) 1H NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) 0.05 (s, 12 H, C H3).13C NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) –0.62 (s, 4 C, C H3). 29Si NMR (benzene): δ (ppm) –9.5 (2, Si (CH3)2) and –70.0 (2, Si Cl2).

3 Results

3.1 Syntheses

The treatment of the cyclic dichlorodiaminosilanes 1 and 2 with 2 equiv of hexaorganodistannoxane leads to the corresponding distannoxodiaminosilanes 3 and 4, with elimination of tributylchlorostannane (equation (1)).

The reactions are run without any solvent, so that the by-product tributylchlorostannane can be removed easily by distillation. There seems to exist an influence of the steric demand of the organic substituent on the nitrogen atoms on the reaction, as the chlorine substitution already occurs at room temperature with phenyl (2), whereas heating to 160 °C is necessary with tert-butyl (1). Also the reaction of 2 with hexabutyldistannoxane is almost quantitative, while the treatment of 1 with hexabutyldistannoxane leads to an equilibrium between 1 and the product 3 in a 60:40 ratio (equation (2)), which can be deduced from the 1H-NMR spectrum of the solution.

The tin compounds 3 and 4 [11–14] are waxy, very viscous and colourless, and can be purified by Kugelrohr distillation at around 220 °C/10–3atm. The 1H-, 13C- and 29Si-NMR spectra are in accord with cyclic molecules of C2 symmetry.

The use of the functionalised molecules 3 and 4 for the synthesis of eight-membered siloxane rings is summarised in equation (3). In these reactions, the polar O–Sn bonds as well as the facile halogen transfer from silicon to tin are the driving forces for the cyclisations. The tin compounds 3 or 4 are added to the equimolar amounts of the silanes R2SiX2 (X = R = Cl; X = R = Br; R = CH3, X = Cl) in diethylether. Whereas the cyclotetrasiloxanes 5a and 5b precipitate after few minutes from the solution, the formation of compound 6 is only completed after stirring for 12 h (equation (3)).

The solvent-free eight-membered siloxane rings are obtained in 40 to 45% yields as white powders, which are almost insoluble in non-polar solvents like toluene, benzene or n-hexane, and slightly soluble in tetrahydrofurane.

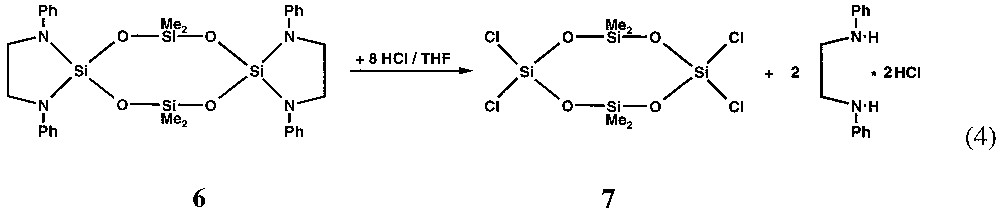

The ethylene-di-amino substituents attached to the spirocyclic silicon atom have bulky organic groups at the nitrogen atoms that seem to favour the formation of rings. Nevertheless they do not prevent from substitution reactions at the aza-silicon atoms as may be seen from equation (4). By this route the mixed chloro/methyl substituted siloxane ring 7 is prepared in tetrahydrofurane with Ph–N(H)–CH2–CH2–N(H)–Ph·2 HCl as by-product.

After filtration of the insoluble amino hydrochloride and removing of all volatile components under reduced pressure, the eight-membered siloxane ring 7 can be sublimed without decomposition as a colourless solid from the oily residue.

3.2 X-ray crystallography

Colourless crystals of 5a, 5b and 6, suitable for X-raydiffraction studies, were obtained by recrystallisation from hot toluene, or by sublimation (7). All measurements were performed either on a Stoe Image Plate (IPDS) or a four-circle single crystal diffractometer (Siemens) at 293 K. A hemisphere of data was collected using ω-scans and graphite monochromatised radiation. Crystallographic data for compounds 5–6 are summarised in the following section 3.3. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by the full-matrix least-squares method on F. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically and hydrogen atoms were kept fixed in calculated positions with C–H = 0.95 Å. Programs used were SHELX-93 and SHELX-97 [15]. The most important parameters for the crystal and the structure determinations have been assembled in Tables 1–3, whereas the molecular structures of 5–7 are illustrated in Figs. 1–3. The refinement of the X-ray structure of compound 7 could not be performed satisfactorily, because only tiny crystals were obtained from 7; here we only give a graphic representation of 7 (R = 12.0%, Fig. 3).

Crystallographic data and data for structure refinements for {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Cl)2SiO}2 (5a), {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Br)2SiO}2 (5b), {[(CH2)2(NPh)2]SiO(Me)2SiO}2 (6) and [(Me)2SiO(Cl)2SiO]2 (7).

| Compound | 5a | 5b | 6 | 7 |

| Emperical formula | C20H44Cl4N4O4Si4 | C20H44Br4N4O4Si4 | C32H40N4O4Si4 | C4H12Cl4O4Si4 |

| M | 658.75 | 836.55 | 657.04 | 378.29 |

| Crystal system | triclinic | triclinic | monoclinic | triclinic |

| Space group | C2/c | P–1 | ||

| Unit cell dimensions | ||||

| a(Å) | 9.708(2) | 9.917(2) | 9.944(2) | 6.454(1) |

| b(Å) | 10.062(2) | 10.165(2) | 16.663(3) | 8.456(9) |

| c(Å) | 10.464(2) | 10.571(2) | 20.490(4) | 8.470(6) |

| α(°) | 97.08(3) | 97.82 | 90 | 80.55(2) |

| β(°) | 116.58(3) | 117.89 | 101.28(3) | 71.04(2) |

| γ(°) | 108.98(3) | 106.81 | 90 | 82.26(2) |

| ν (Å3) | 819.6(3) | 854.0(3) | 3329.5(1) | 429.6(2) |

| Z | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Dcalc (g cm–3) | 1.335 | 1.599 | 0.221 | 1.462 |

| Absorption coefficient | 0.539 | 4.883 | 1392 | 0.963 |

| F(000) | 348 | 406 | 1392 | 192 |

| Crystal size (mm) | 0.2 × 0.3 × 0.2 | 0.2 × 0.3 × 0.1 | 0.2 × 0.3 × 0.2 | 0.1 × 0.3 × 0.4 |

| θ range | 2.61–23.93 | 2.21–25.00 | 2.42–24.13 | 3.31–24.03 |

| Reflections collected | 5027 | 3014 | 10 309 | 2584 |

| Independent reflections | 2332 [R(int) = 0.0601] | 3014 | 2611 [R(int) = 0.0519] | 2584 |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data/restraints/parameters | 2332/0/163 | 3014/0/163 | 2611/0/199 | 1211/0/73 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.111 | 1.121 | 1.032 | 1.148 |

| Final R indices (I >2 σ(I)) | R1 = 0.0449 | R1 = 0.0622 | R1 = 0.0371 | R1 = 0.1201 |

| wR2 = 0.1158 | wR2 = 0.1432 | wR2 = 0.0898 | wR2 = 0.2964 | |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0478 | R1 = 0.0909 | R1 = 0.0509 | R1 = 0.1361 |

| wR2 = 0.1181 | wR2 = 0.1635 | wR2 = 0.0948 | wR2 = 0.3322 | |

| Largest diffraction peak and hole (e Å–3) | 0.527/–0.364 | 1.706/–0.503 | 0.205/–0.218 | 0.563/–0.767 |

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (deg) (e.s.d.s. in parentheses) for {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Cl)2SiO}2 (5a) and {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Br)2SiO}2 (5b).

| 5a (X = Cl) | 5b (X = Br) | |

| Bond lengths | ||

| Si(1)–O(1) | 1.6461(2) | 1.638(5) |

| Si(1)–O(2) | 1.6368(2) | 1.632(5) |

| Si(2)–O(1) | 1.5928(2) | 1.579(5) |

| Si(2)–O(2)# | 1.5791(2) | 1.576(5) |

| Si(1)–N(1) | 1.700(2) | 1.692(5) |

| Si(1)–N(2) | 1.692(2) | 1.724(6) |

| Si(2)–X(1) | 2.0362(1) | 2.199(2) |

| Si(2)–X(2) | 2.0265(2) | 2.195(3) |

| N(1)–C(1) | 1.482(3) | 1.433(9) |

| N(1)–C(3) | 1.466(4) | 1.502(9) |

| N(2)–C(2) | 1.480(4) | 1.466(1) |

| N(2)–C(7) | 1.471(4) | 1.451(9) |

| C(1)–C(2) | 1.494(4) | 1.464(2) |

| Bond angles | ||

| O(1)–Si(1)–O(2) | 102.29(2) | 102.0(3) |

| O(1)–Si(2)–O(2)# | 114.21(1) | 113.5(3) |

| Si(1)–O(1)–Si(2) | 159.94(1) | 158.0(4) |

| Si(1)–O(2)–Si(2)# | 163.36(2) | 166.5(4) |

| N(1)–Si(1)–N(2) | 97.02(2) | 96.5(3) |

| X(1)–Si(2)–X(2) | 106.69(5) | 106.34(9) |

| C(1)–N(1)–Si(1) | 117.8(2) | 110.7(5) |

| C(2)–N(2)–Si(1) | 107.66(2) | 106.1(5) |

| N(1)–C(1)–C(2) | 107.1(2) | 109.0(7) |

| N(2)–C(2)–C(1) | 107.3(2) | 111.4(7) |

Selected bond distances (Å) and angles (deg) (e.s.d.s. in parentheses) for {[(CH2)N2Ph2]Si(Me2SiO2)}2 (6).

| Bond lengths | Bond angles | ||

| Si(1)–O(1) | 1.602(2) | O(1)–Si(1)–O(2) | 106.42(8) |

| Si(1)–O(2) | 1.6107(2) | O(1)–Si(2)–O(2)# | 109.57(8) |

| Si(2)–O(1) | 1.6235(2) | Si(1)–O(1)–Si(2) | 156.53(1) |

| Si(2)–O(2)# | 1.6135(2) | Si(1)–O(2)–Si(2)# | 164.93(1) |

| Si(1)–N(1) | 1.7149(2) | N(1)–Si(1)–N(2) | 95.21(8) |

| Si(1)–N(2) | 1.7142(2) | C(15)–Si(2)–C(16) | 112.50(2) |

| Si(2)–C(15) | 1.838(3) | C(1)–N(1)–Si(1) | 112.32(2) |

| Si(2)–C(16) | 1.836(3) | C(2)–N(2)–Si(1) | 112.30(2) |

| N(1)–C(1) | 1.468 | N(1)–C(1)–C(2) | 110.02(2) |

| N(1)–C(3) | 1.402 | N(2)–C(2)–C(1) | 110.03(2) |

| N(2)–C(2) | 1.468 | ||

| N(2)–C(7) | 1.402(3) | ||

| C(1)–C(2) | 1.397(3) |

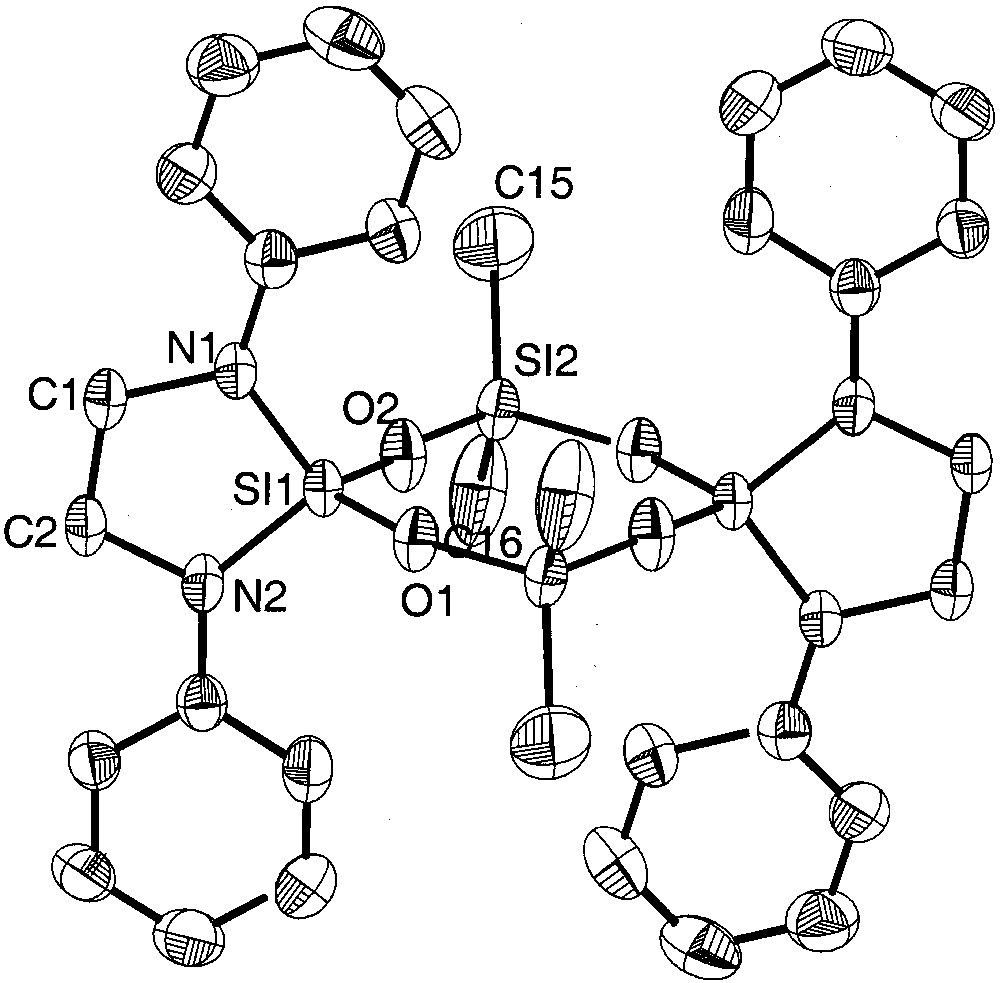

Molecular structure of {[(CH2)2N2(Ph)2]SiO(Me)2SiO}2(6). Thermal ellipsoids are plotted at the 50% probability level; the molecule is centrosymmetric.

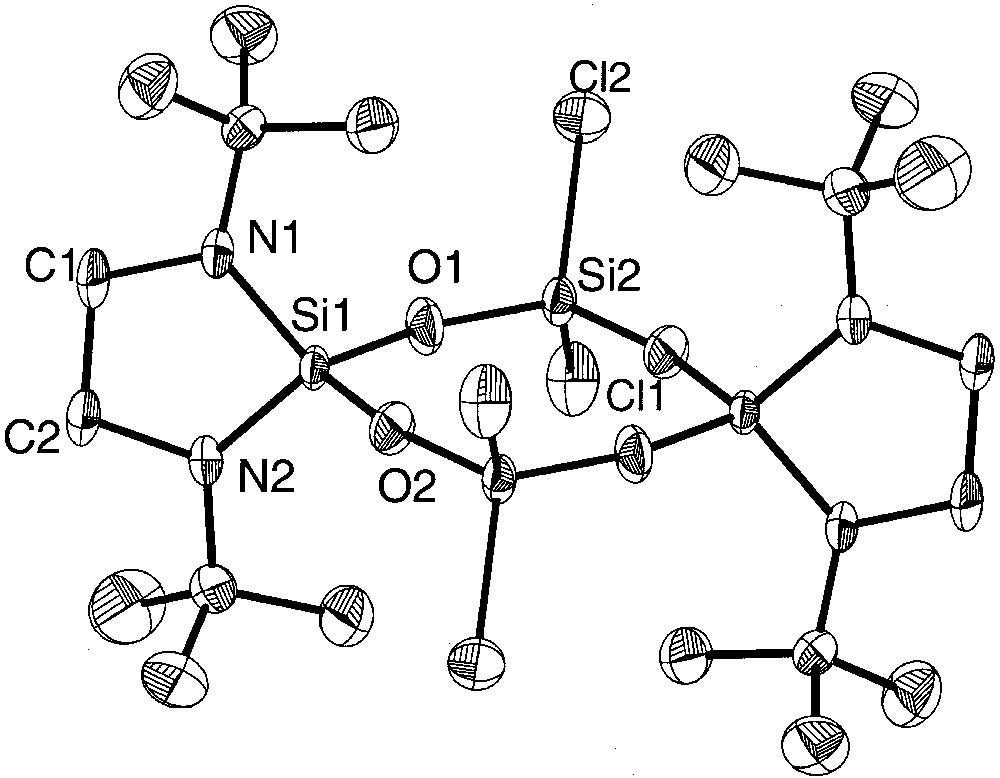

Molecular structure of centrosymmetric {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Cl)2SiO}2(5a) with thermal ellipsoids at the 50% level. The corresponding bromo derivative {[(CH2)2(NtBu)2]SiO(Br)2SiO}2 (5b) is isostructural and isotypic.

Molecular structure of centrosymmetric [(Me)2SiO(Cl)2SiO]2(7). Thermal ellipsoids are plotted at the 50% level.

3.3 Discussion of the structures

Whereas in the eight-membered siloxane rings 6 and 7 the variation of the dihedral angles Si–O–Si–O and O–Si–O-Si is remarkable (6: 3.6–34.6°, 7: 2.5–18.4°) and follow the trend that eight-membered siloxane rings differ from the planarity in contrast to planar six-membered siloxane rings [3], the bis(amino)-chloro derivative 5a (variation of dihedral angles: 4.4–8.5°) and the bis(amino)-bromo derivatives 5b (variation of dihedral angles: 0.4–4.3°) can be considered as almost planar. All molecules 5a, 5b, 6 and 7 have crystallographic Ci symmetry and deviate in the case of 5a and 5b (not considering the tert-butyl groups) only negligibly from D2h, while in 6 and 7 the twist within the eight-membered rings is more remarkable.

As we have found earlier, a gain in electronegativity of substituents bonded to the silicon atoms leads to a shortening of the Si–O bonds and an expansion of the O–Si–O angles [7]. Whereas the evolution of Si-O bonds and Si–O-Si angles in cyclotrisiloxanes is limited by the ring size and consequently ring strain (maximal angles ~133°), in cyclotetrasiloxanes the Si–O–Si bonding angles are larger (~145°) and the Si-O bonding distances usually shorter.

The electronegative chlorine or bromine ligands in 5a and 5b result in an electron withdrawal from the silicon atoms, leading to a strong shortening of the adjacent Si–O–bonds. In 5a, the Si–O bond lengths of the chlorine substituted silicon atoms (mean: 1.586(7) Å) are in average similar to those found in octachlorotetrasiloxane (Cl2SiO)4 (mean: 1.584(9) Å) [3]. Although we expected longer Si–O distances in the bromine derivative 5b due to lower electronegativity of the bromine atom in comparison to chlorine (E.N. (Pauling): Cl 3.1, Br 2.9 [16]), we found slightly shorter silicon oxygen bonds of 1.578(8) Å (mean value). At the spirocyclicly and amino bonded silicon atoms the Si–O bonds are longer in the two derivatives: in 5a the average length is 1.642(9) Å, in 5b 1.635(8) Å, longer as in comparable compounds [17–19]. Interestingly, the Si–O distances of nitrogen-bonded Si(1) (mean: 1.609(1) Å) in compound 6 are shorter than those of methyl-bonded Si(2) (mean: 1.619(5) Å). Apparently, in this compound the amino substituted silicon atom Si(1) has an electron lack compared to Si(2), which has the more electropositive ligands.

Generally, the Si–O–Si angles in cyclotetrasiloxanes show a large variation according to the flexibility of Si–O–Si–O chains and may differ by more than 10° [20–24]. For example, in octachlorocyclotetrasiloxane, the values range from 154.5° to 165.2° [3]; this effect is normally attributed to the packing of the molecules in the solid state. In the present chlorine and bromine derivative 5a and 5b, the angle differences are relatively small (5a: 159.94(2)° to 163.36(3)°, 5b: 158.0(4)° to 166.5(4)°). In the mixed methyl and chloro derivate 7, the Si–O–Si angles range from 153.7° to 164.8°.

The Si–Cl distances in 5a (2.065(6) and 2.0362(2) Å) are longer than in the octachloroderivative (Cl2SiO)4 (mean: 2.000(7) Å) [3] and in hexachlorodisiloxane (Cl3Si)2O (by electron diffraction: 2.011(3) Å) [25]. The silicon–bromine bonds in 5b are in the common range [26, 27]. The SiN2C2 five-membered rings in 5a and 5b are twisted as may be deduced from the sum of the angles within the cycles (5a: 527.26°; 5b: 533.7°), whereas in 6 the corresponding sum is 539.88°, compatible with an almost planar cycle (theoretical value: 540°). According to the deviation from planarity of the five-membered rings in 5a and 5b, the average angle sums at the nitrogen atoms differ from 360° (356,28° and 358.35°), whereas in 6 the nitrogen atoms have a planar coordination sphere. The Si–N bonds in 5a, b and 6 range from 1.692(5) Å to 1.724(6) Å and are comparable to literature values [9, 28–31].

3.4 Spectroscopy

In 29Si-NMR spectra chlorosiloxanes can usually easily be recognised due to their specific range of chemical displacements and this even holds when dichlorosiloxy groups are combined with other siloxy groups [32–34]. The substitution of chloro atoms in the cyclic bis(amino)dichlorosilanes 1 and 2 by the oxygen atoms of the OSnBu3 groups is accompanied by a significant low field shift from –33.3 (1) and –34.6 ppm (2) to –56.2 (3) and -62.3 ppm (4).

In acyclic (Cl2SiO)n units, the 29Si resonance signal occurs around –71 ppm [35, 36], whereas for the chloro substituted cyclotrisiloxanes (Cl2SiO)3, the 29Si NMR signal is found at –58.2 ppm [32, 36]. This shift between the cyclic and acyclic compound can be explained by the ring tension of the six-membered ring [32]. For the cyclic chloro-and methyl-substituted eight-membered ring 7 (of crystallographic Ci symmetry), two 29Si NMR signals are observed at –9.5 and –70.0 ppm. The NMR resonance for the dimethylsilyl group at –9.5 ppm in 7 appears in the expected range [33, 36]. The second 29Si signal in the NMR spectrum at –70.0 ppm (SiCl2) however is closer to an open chain (Cl2SiO)n structure than to the six-membered ring, in accord of less strain in the eight-membered Si4O4 ring. On the same line, the 29Si NMR signal for the octachlorocyclotetrasiloxane (Cl2SiO)4 is found at –69.2 ppm [32, 36].

4 Supplementary material

Crystallographic data for the structural analyses have been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, CCDC 198174 (5a), 198175 (5b), 198176 (6).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for the financial support within the framework of the Schwerpunktprogramm ‘New Phenomena in Silicon Chemistry’.