1. Introduction: copper in human health and disease

After iron and zinc, copper is the third essential metal ion in living systems [1]. The highest concentrations of copper are found in liver and brain. The copper concentration in human frontal lobe and cerebellum is ranging from 60 to 110 μM [2]. In living organisms, copper exists in the oxidized Cu(II) and reduced Cu(I) forms. In biological conditions, the interconversion between these two oxidation states is easy and facilitates the role of this metal as catalytic co-factor in various copper enzymes involved in electron transfers and oxidations.

Copper ions are found in many different metalloenzymes (laccases, tyrosinase, superoxide dismutase, ascorbate oxidase, cytochrome-c oxidase to cite a few ones) and metalloproteins (hemocyanin, ceruloplasmin) [3, 4]. Among these copper proteins involved in vital processes, cytochrome-c oxidase is a large transmembrane terminal heme/copper oxidase of the respiratory electron transport chain. Its redox centers involved in electron transport consist of two heme moieties and two copper centers that catalyze the reduction of dioxygen to water with the concomittant pumping of four protons through the mitochondrial membrane [5] (Equation (1)).

| \begin {eqnarray} \mathrm {O}_2 \; \xrightarrow {4 \mathrm {e}^{-}, 4 \mathrm {H}^{+}} \; 2 \mathrm {H}_2 \mathrm {O} \label {eqn1} \end {eqnarray} | (1) |

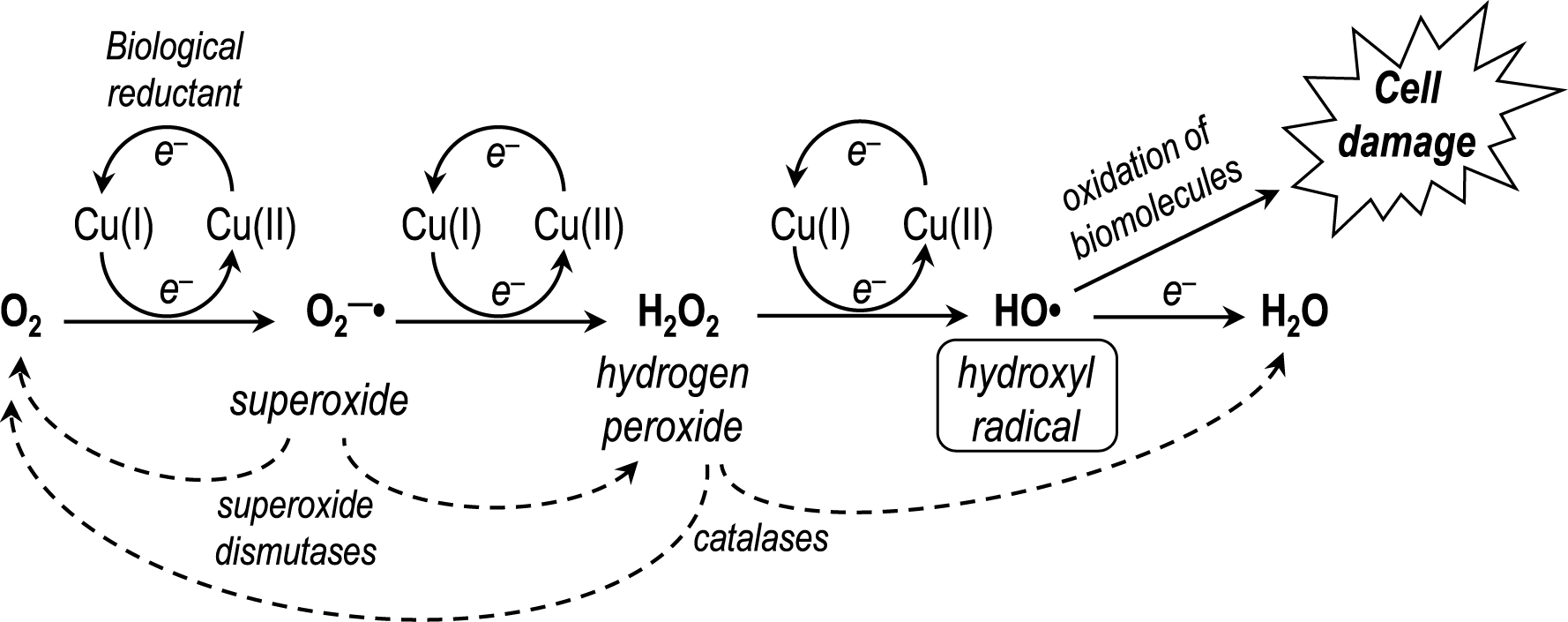

Since the air-stable oxidation state +II of copper can be easily reduced to the highly reactive state (+I) by endogenous reducing agents (e.g., ascorbate, glutathione, NADPH) [6], its acquisition, distribution and regulation in living systems is strictly controlled by copper carriers and chaperone proteins [7]. As a low-valent transition metal ion, Cu(I) behaves in the same way as Fe(II), being able to induce the electron-by-electron reduction of dioxygen to water in all aerobic organisms (Scheme 1). This catalytic reaction is potentially deleterious because it produces superoxide radical anion $\mathrm{O}_{2}^{\bullet -}$, then hydrogen peroxide H2O2 and finally hydroxyl radical HO∙, the most aggressive form among the reactive/reduced oxygen species (ROS).

Step-by-step reduction of dioxygen catalyzed by low-valent transition metals such as Cu(I) or Fe(II).

Superoxide is a relatively mild reductant and hydrogen peroxide is the required cofactor of the ubiquitous peroxidases. In healthy organisms, the concentrations of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide are strictly controlled by metallo-enzymes. The efficient superoxide dismutases (SODs), Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase (= SOD-1), to name one of them, have a key role in the regulation of this metabolic pathway, by converting two superoxide radical anions to molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide through the redox activity of its copper centre, while zinc plays a structural role (Equation (2)).

Cu/Zn-SOD (= SOD-1) is present in nearly all compartments of human cells, nucleus, mitochondria, cytosol, and peroxisomes.

| \begin {eqnarray} 2 \mathrm {O}_2^{\bullet -}\; \xrightarrow {2 \mathrm {H}^{+}}\; \mathrm {O}_2 + \mathrm {H}_2 \mathrm {O}_2 \label {eqn2} \end {eqnarray} | (2) |

Hydrogen peroxide is used as cofactor by peroxidases, but any excess of production of this peroxide is controlled by catalases that are highly efficient at H2O2 disproportionation. In the case of H2O2 overproduction, the three-electron reduction product of dioxygen, hydroxyl radical HO∙, is produced. This radical is the strongest oxidizing agent (standard redox potential = 2.8 V/NHE) after fluorine gas (2.9 V/NHE) and, unlike $\mathrm{O}_{2}^{\bullet -}$ or H2O2, no specific detoxifying enzymes exist for HO∙. At diffusion-controlled rates, HO∙ hydroxylates aliphatic C–H bonds, or performs the one-electron oxidation of rather inert molecules, or modifies unsaturated compounds by addition [8]. All biomolecules of living organisms can be quickly oxidized by HO∙, leading to extensive damage up to cell death. The only way to prevent the formation of this deleterious radical is to control the upstream reduction of molecular oxygen. Involvement of an oxidative stress induced by misregulated copper in the brain has been documented as a key feature of Alzheimer’s disease and proposed to be important for the development of the brain pathology [9, 10, 11]. It is also well known that the deregulation of copper homeostasis is involved in other inherited or sporadic neurodegenerative pathologies like Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis that is caused by mutations of SOD-1 [12], or prion-mediated encephalopathies [13]. Copper ions are also essential for the function of several brain metalloenzymes like tyrosinase [14] or dopamine β-hydroxylase [15].

In addition, any deficiency of a human copper carrier protein involved in the regulation of copper uptake, may generate a pathology. This is the case for Wilson’s disease, a genetic condition caused by mutations of the Atp7b gene coding for the copper carrier ATP7B in charge of excreting copper from liver to bile. Impairment of ATP7B causes massive accumulation of copper in liver, brain, and other organs, resulting in liver disease and neurological disorders [16, 17, 18]. Moreover, copper is essential for efficient iron and zinc trafficking in mammals. The major copper transporter ceruloplasmin exhibits a ferroxidase activity that promotes the Fe(II) oxidation to facilitate the iron loading into ferritin, and Zn(II) is a substrate of ferroportin [19]. So it should be noted that the roles of these three vital metal ions, copper, zinc, and iron, are often interconnected in different proteins or enzymes. Consequently, any metal chelator, if considered as drug candidate, should be specific for one of these metal ions to avoid as much as possible perturbations of metalloproteins dependent on the two other metal ions. This is a prerequisite point in the rational design of a copper ligand for being beneficial in the therapy of a copper-related disease.

As bioinorganic chemists initially involved in DNA cleavage by metal complexes, our group became interested by using copper complexes as DNA cleavers (Section 2 of the present review article), then some copper ligands were designed for antitumor activity (Sections 3 and 6). Different series of specific copper chelators were then developed as potential drugs to treat Alzheimer’s disease (Section 4) and Wilson’s disease (Section 5). In relation to the state of the art, the present review is therefore focused on the last twenty-five years of research on copper ligands with potential therapeutic interest performed in our research group, especially on the step-by-step rational design of metal-selective and biologically efficient drugs.

2. Copper complexes as DNA cleavers

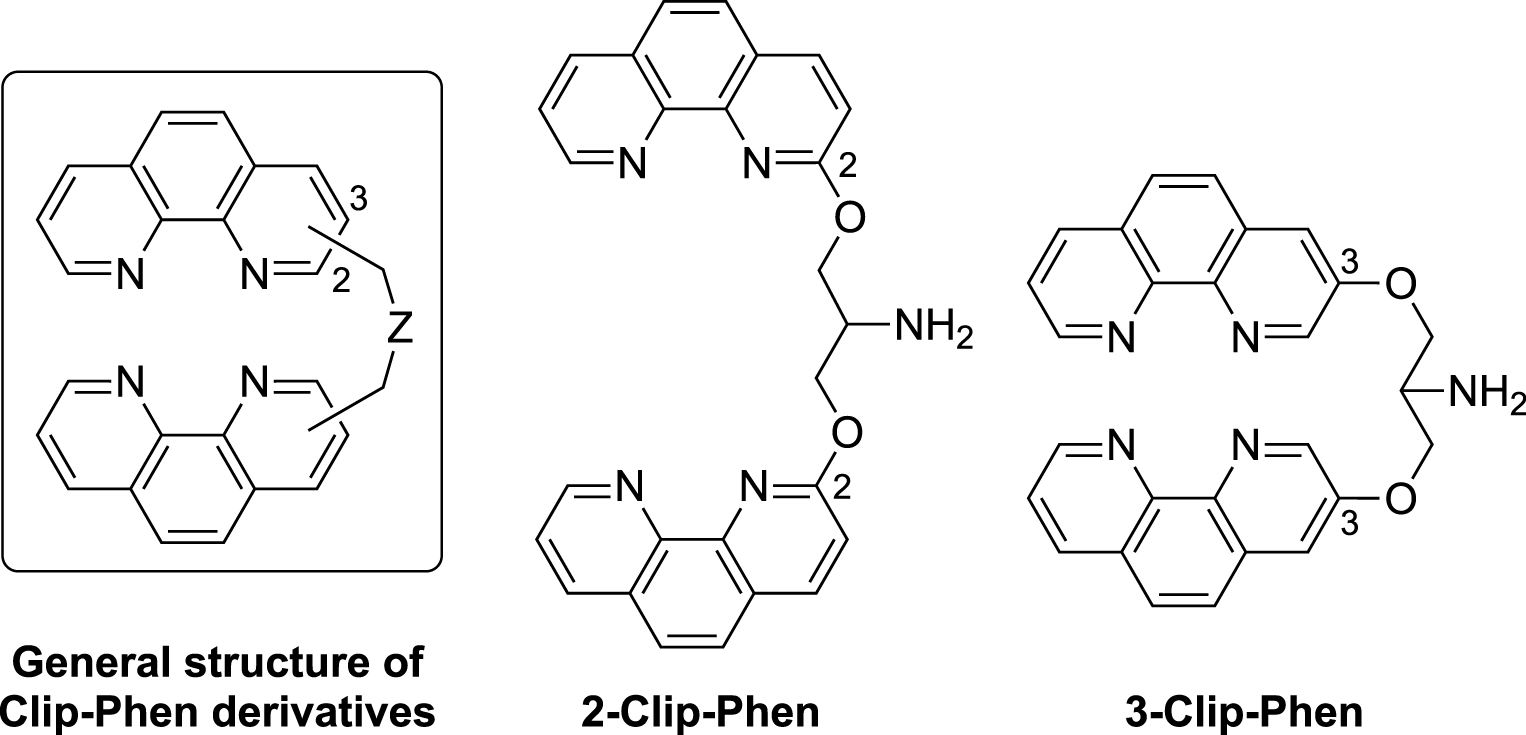

Among the various metal complexes developed over the last three decades as artificial nucleases, copper complexes of 1,10-phenanthroline (Phen) have been widely used as DNA cleavers [20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. The versatile Phen ligand is able to chelate copper ions as redox-active Cu(Phen) and Cu(Phen)2 complexes (for a general review on the chemistry of phenanthrolines, see Ref. [24]). Interaction of the redox-active Cu(I)/Cu(II)–phenanthroline complexes in the minor groove of double-stranded DNA in the presence of H2O2, triggers the oxidation of C1′ and C4′ of 2-deoxyribose units, resulting in single-strand DNA cleavage [20, 21]. This cleavage can also be achieved by aerobic oxidation in the presence of a reducing agent. Cu(Phen)2 was found significantly more active than Cu(Phen), but the association constant for the second Phen ligand onto the copper ion is too low to enhance DNA oxidation at submicromolar concentrations (logKapp = 5.5) [25]. Consequently, chelators named “Clip-Phen” were prepared, containing two Phen residues linked through their C2 or C3 positions by an adjustable bridge, to favor the coordination of two Phen units around a single copper ion (Figure 1) [26, 27]. The efficiency of oxidative DNA cleavage by Cu–Clip-Phen complexes, under aerobic and physiological conditions in the presence of a reductant, was evaluated by quantification of the cleavage of supercoiled circular bacteriophage ΦX174 DNA (form I) into relaxed (form II) and circular (form III) forms. In these conditions, Cu–Clip-Phen complexes exhibited a nuclease activity that was dramatically higher than that of Cu–1,10-phenanthroline [26].

Structures of the covalently linked bis-phenanthroline ligands, 2-Clip-Phen and 3-Clip-Phen.

The DNase activity of Clip-Phen was higher when the bridge was linked at the C3 position of the Phen moiety (3-Clip-Phen series) compared to the C2 position (2-Clip-Phen series) and when the bridge contained three methylene units [27, 28]. The most efficient chelator of this series was 3-Clip-Phen (Figure 1) with a serinol bridge at C3 position of the Phen rings, being 20–30 times more active as DNA cleaver than its 2-Clip-Phen analog [27, 28]. In fact, 2-Clip-Phen in the presence of CuCl2 (1:1 molar ratio) resulted in an incomplete (70%) cleavage of ΦX174 form I into relaxed form II (30% of remaining form I) whereas, in the same conditions, 3-Clip-Phen resulted in the complete cleavage of form I into form II (35%) and circular form III (65%), with an intense smear corresponding to smaller DNA fragments.

In addition, the serinol bridge between the two Phen units allowed, via its primary aliphatic amine, the vectorization and modulation of the binding domain in these DNA cleavers. As expected, the attachment of spermine, which has high affinity for the minor groove of double helix DNA, to 2-Clip-Phen afforded a new spermine–phenanthroline conjugate with an enhanced nuclease efficacy [29].

The electrochemical study of the 2- and 3-Clip-Phen series indicated that the 2-Clip-Phen ligands are better to stabilize the tetrahedral Cu(I) state of their complexes in comparison to the Cu(II) state. On the other hand, 3-Clip-Phen derivatives facilitate the stabilization of the corresponding Cu(II) complexes with a quasi-irreversible Cu(II) → Cu(I) reduction, suggesting that the reduced DNA cleavage efficacy of Cu–2-Clip-Phen complexes might be correlated with the higher stabilization of the cuprous oxidation state. However, the absence of strict correlation between the redox properties of the copper complexes and their DNA cleavage efficacy suggests that steric or electrostatic parameters of the DNA interactions also take part in the modulation of the nuclease activity of these copper complexes.

Noteworthy, several complexes of 2- or 3-Clip-Phen with Cu(II) crystallized as a double-helical structure of stoichiometry Cu2L2, while monomeric CuL species, with various geometries, were predominant in solution [28]. The structure and reactivity of these copper complexes appear to be particularly versatile, a feature that opens the way for potential uses as biological tools.

3. Copper ligands/complexes with antitumor activity

Since the registration of cisplatin in the early 1980s, the role of metal ligands and complexes in cancer research has been the subject of many studies until now (for a recent review, see Ref. [30]). The efficacy of the copper complexes of Clip-Phen as DNA cleavers suggested that these chelators might also be considered as therapeutic agents against cancer. In fact, research on the cytostatic and potential antitumor activities of substituted Phen derivatives or related ligands metalated with copper or other various metals has been investigated in parallel to their DNase activity [31, 32, 33, 34] and has remained an active research field until recent years, with the aim of developing novel metal-based anticancer drugs [35, 36, 37].

In this context, the cytostatic properties of a series of 3-Clip-Phen derivatives were evaluated on the classic L1210 murine leukemia cell line. The concentration inhibiting the cell growth by 50% after 48 h (IC50) of 3-Clip-Phen was close to that of Phen itself (1.15 and 2.5 μM, respectively), although Cu–3-Clip-Phen was a better DNA cleaver than Cu(Phen)2 [33]. This result suggested that the cytostatic activity was not strictly correlated to the DNase activity.

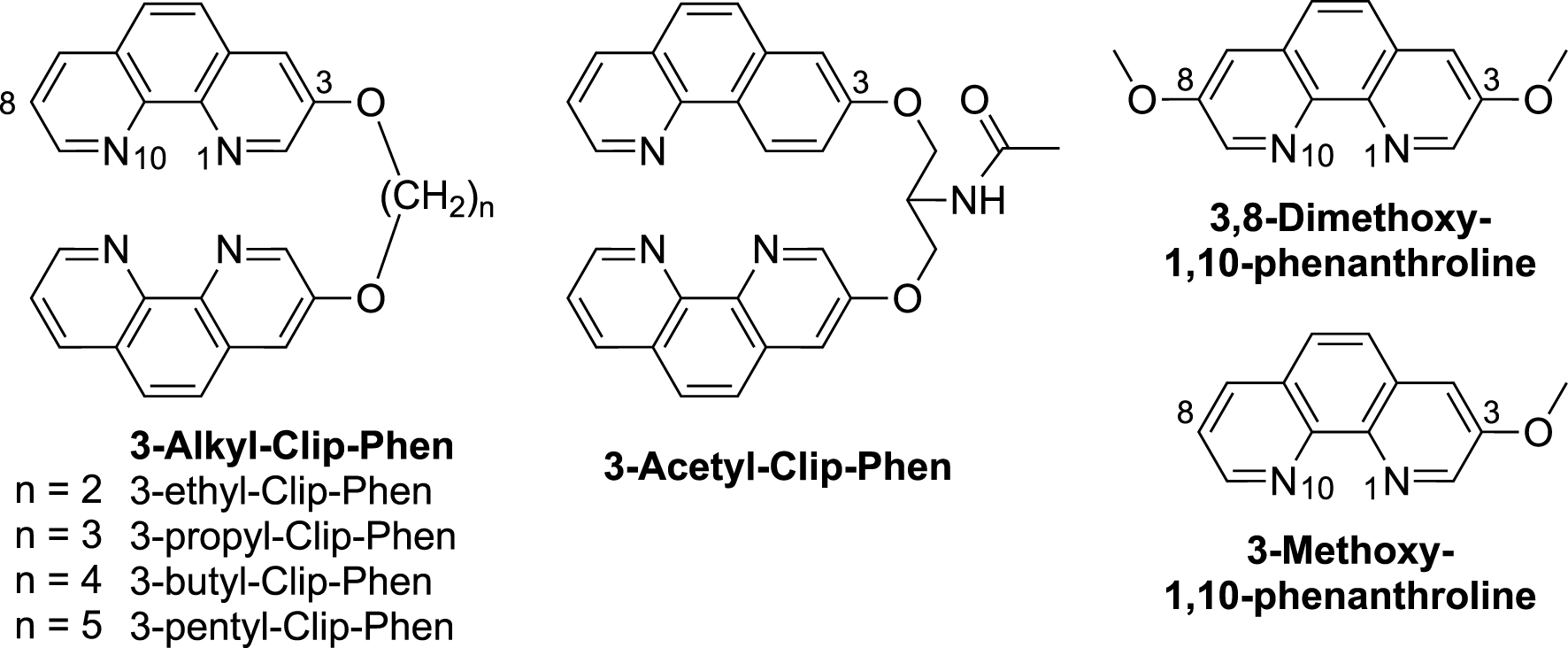

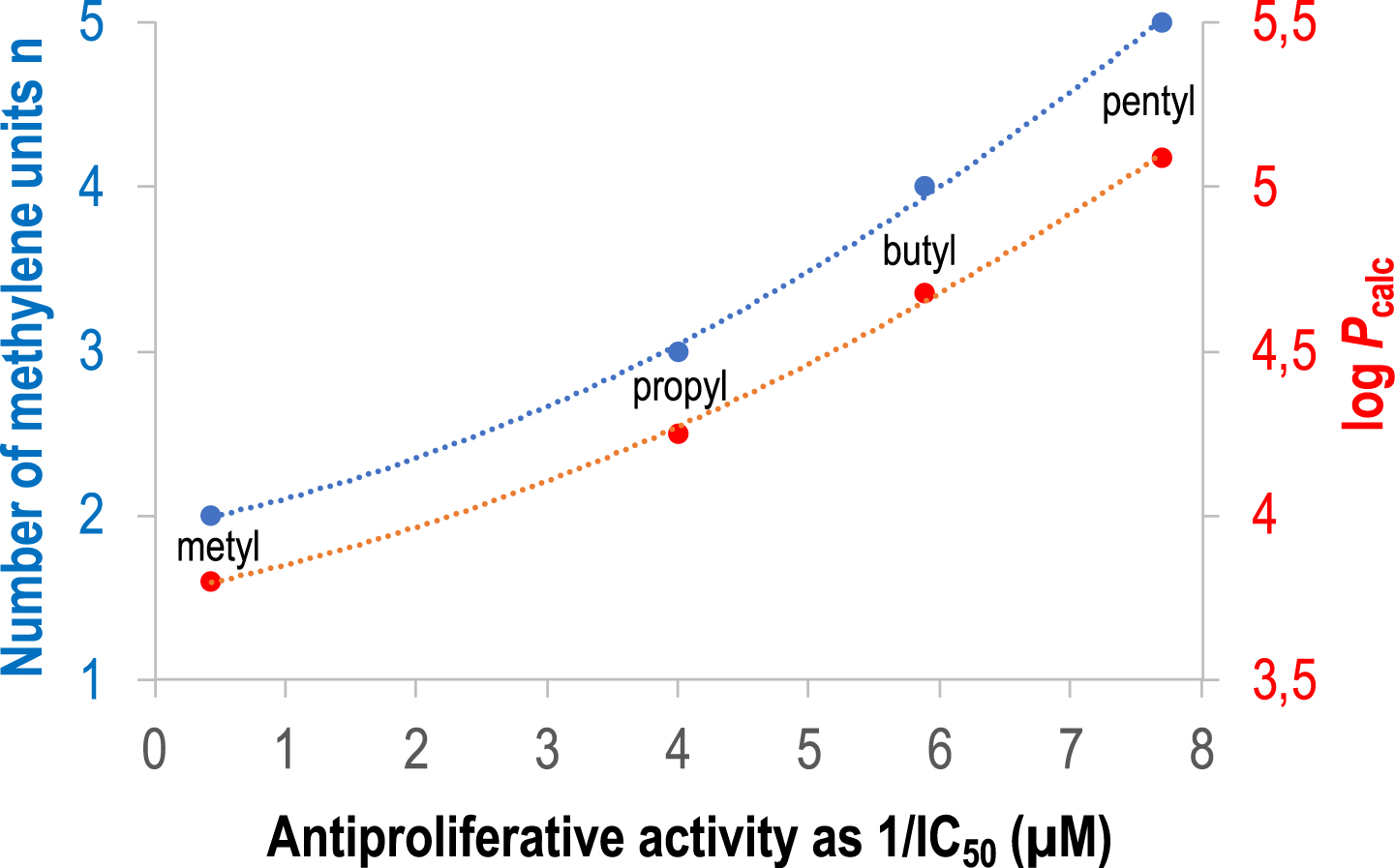

Conversely, 3-propyl-Clip-Phen, with a simple aliphatic linker (Figure 2), exhibited a significantly higher activity against L1210 cells (IC50 = 0.25 μM) compared to 3-Clip-Phen (Figure 1). Analogs of 3-propyl-Clip-Phen containing two to five methylene units in the linker (3-alkyl-Clip-phen series) (Figure 2), were also evaluated. Their activity was significantly correlated to their number of methylene units in the linker, itself correlated to hydrophobicity (Figure 3). The longer the linker, the more active the compound was, with an IC50 value of 0.13 μM for 3-pentyl-Clip-phen. In order to investigate whether the hydrophilic primary amine of the linker of 3-Clip-phen (logPcalc = 2.47, IC50 = 1.15 μM) could hamper its biological activity, this ligand was compared to the slightly more hydrophobic 3-acetyl-Clip-Phen (logPcalc = 2.80). However, the antiproliferative activity of 3-acetyl-Clip-Phen was lower at 5 μM, indicating that the correlation between biological activity and log Pcalc was limited to the 3-aliphatic-Clip-Phen series [33].

Structures of alkyl substituted 3-Clip-Phen ligands, and 3,8-substituted-1,10-phenanthrolines.

Antiproliferative activity of 3-alkyl-Clip-Phen derivatives measured as 1/IC50 value with respect to the number of methylene units in the linker (n, blue trace) or to the hydrophobicity (logPcalc, red trace). The dotted lines stand for polynomial trend curves of degree 2.

The putative role of the alkoxy substituent at the C3-position in the phenanthroline of Clip-Phen derivatives was evaluated by comparing their activities to that of monomeric Phen derivatives, 3-methoxy- and 3,8-dimethoxy-1,10-phenantholine. The IC50 values of 3-methoxy- and 3,8-dimethoxy-1,10-phenantholine were 1.5 μM and 1.4 μM, respectively, in the same range as for Phen itself (2.5 μM), suggesting that the alkoxy substituents at the C3- and C8-position were not responsible for the higher cytostatic activity of 3-alkyl-Clip-Phen. On the other hand, the attachment position of the linker on the phenanthroline units is an important parameter, since 2-propyl-Clip-Phen exhibited a much poorer activity (IC50 value > 100 μM) than its regio-isomer 3-propyl-Clip-Phen (1.15 μM) [33].

The conjugation of 3-Clip-Phen with DNA binders and/or cell penetration agents such as spermine or polyarginine (Arg)9 did not increase the antiproliferative activity. The IC50 values of 3-Clip-Phen–spermine and 3-Clip-Phen–(Arg)9 were 12 μM and 1.9 μM, respectively, against L1210 cells [33], despite the fact that 3-Clip-Phen–spermine exhibited a much higher nuclease activity than 3-Clip-Phen on supercoiled ΦX174 DNA [29].

Importantly, Cu(II) complexes of Clip-Phen derivatives were prepared, and their cytostatic activities were evaluated. While complexation of copper failed to improve the activity of 3-Clip-Phen derivatives regardless of the composition of the linker, the activity of 2-propyl-Clip-Phen dramatically increased with copper complexation (IC50 = 2 μM, compared to IC50 > 100 μM for the free ligand). These results confirmed that the attachment position of the linker induced large variations in the biological properties of Clip-Phen derivatives [33].

4. Copper chelators against Alzheimer’s disease

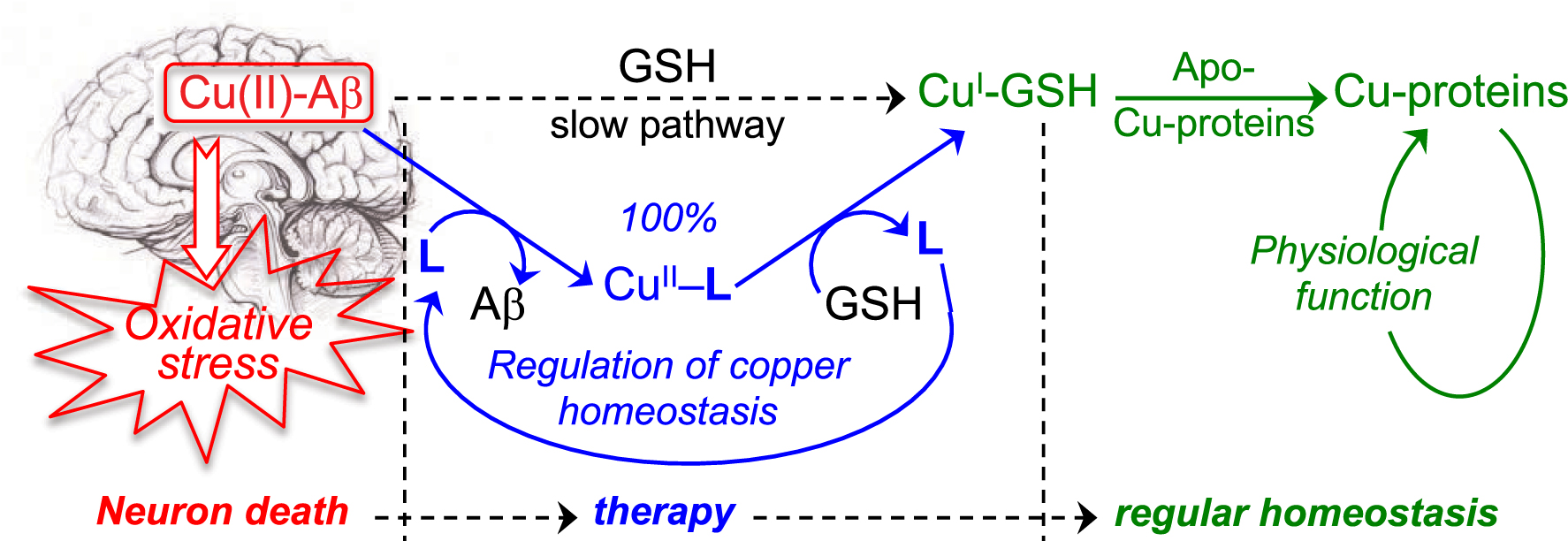

Among the various putative targets involved in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the loss of metal ion homeostasis in AD brain is well documented [38, 39, 40, 41]. Post-mortem analyses of the brain of patients with AD indicated that amyloid plaques contain an excess of copper, iron, and zinc by a factor of 5.7, 2.8, and 3.1, respectively, compared to the levels of normal brains [9]. Copper–amyloid complexes, in the presence of endogenous reductants, catalyze the reduction of dioxygen to generate reduced ROS (Scheme 1) [40, 42]. Production of ROS is the molecular signature of chronic inflammation reported in AD brain and involved in neuronal death [43]. In addition, copper ions sequestered in amyloid plaques may be responsible for a deficit in copper for cerebral copper-dependent enzymes, like superoxide dismutase-1, [44] or copper oxidases involved in the biosynthesis of neurotransmitters. Therefore, restoration of copper homeostasis in the brain is a multifunction drug target that requires the design of specific chelators [11, 38, 45, 46]. Because of the deleterious oxidative stress catalyzed by out-of-control redox-active metal ions, this approach should be considered an essential strategy among all various attempts in AD drug design.

4.1. Clioquinol (CQ) and PBT2

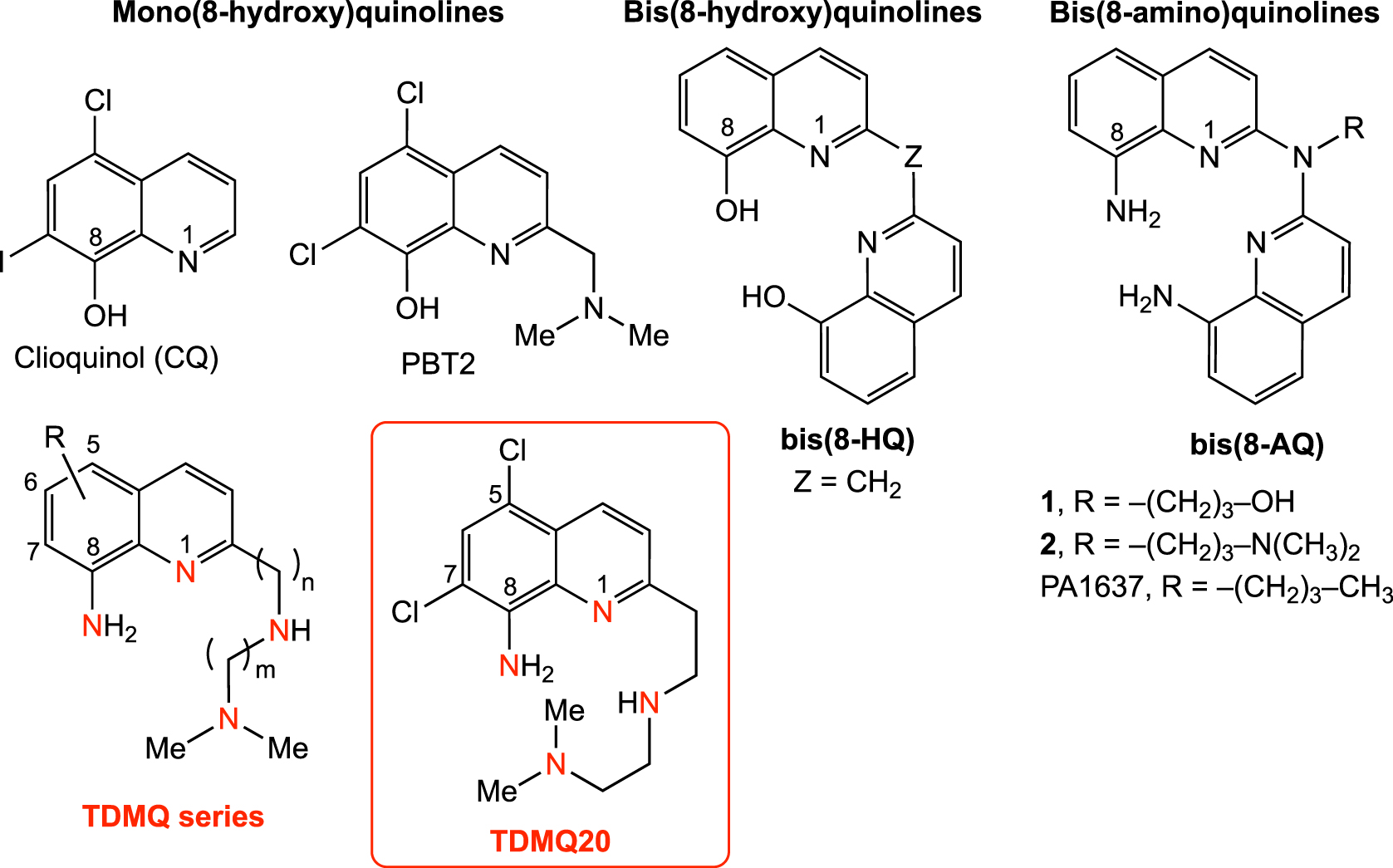

The 8-hydroxyquinoline derivatives clioquinol (CQ) and PBT2 (Figure 4) have been the first copper/zinc ligands considered as potential anti-AD agents to limit the interactions between metal ions and amyloid peptide (Aβ). Clioquinol was able to decrease Aβ deposits in brain and to improve learning and memory abilities of transgenic AD mice [47, 48]. Unfortunately, this simple chelator, previously used as antifungal and antiprotozoal drug, was withdrawn from the market in 1983, due to its neurotoxicity attributed to zinc chelation [15, 49]. In fact, the 8-hydroxyquinolines are non-specific metal chelators [50, 51], and the affinity constant of CQ for Cu(II) is only one order of magnitude higher than that for Zn(II) (logK = 10 and 9, respectively) [38, 52]. In this series, PBT2 [38] was less toxic [48]. However, phase II clinical trial of PBT2 as anti-AD drug was stopped due to its lack of efficacy [53].

Structures of copper chelators developed as drugs against Alzheimer’s disease. Z stands for an adjustable linker.

In fact, CQ and PBT2 are bi- or tridentate ligands. Consequently, their corresponding Cu(II) complexes have a 1:2 metal/ligand stoichiometry [38, 54]. Moreover, addition of stoichiometric amounts of CQ or PBT2 to Cu(II)–Aβ in vitro does not efficiently remove Cu from Cu(II)–Aβ, but generates stable ternary CQ– or PBT2– Cu(II)–Aβ complexes [54, 55]. Since 8-hydroxyquinolines are unable to extract copper(II) from soluble amyloids, these ligands should not be considered as regulators of the copper homeostasis in AD brains. Moreover, their flexible coordination properties allow them to accommodate either Cu(II) or Cu(I), reducing their capacity to inhibit the oxidative stress induced by Cu–Aβ [56].

Additionnally, copper is a required cofactor for several essential metalloenzymes, for example, for the tyrosinase that produces L-DOPA from tyrosine and catecholamine neurotransmitters [14]. Circadian rhythm dysfunction occurs in AD, and copper was recently reported to modulate rest–activity cycles via norepinephrine produced by copper enzyme dopamine β-hydroxylase [15]. These data indicate that the chance to get an efficient copper ligand from the shelves to treat copper-related disease are limited, due to the necessity of understanding the whole picture of the various parameters in copper coordination chemistry. Specific copper chelators should result from a rational design in order to create drugs as specific as possible. These ligands should not disrupt the regular activity of copper enzymes or proteins and must have suitable pharmacological and safety profiles. Moreover, they should be able to cross the blood–brain barrier after an oral administration, to avoid any painful mode of administration. The following sections are reporting our successive works to reach this goal.

4.2. Bis(8-hydroxyquinolines)

In line with our expertise on Clip-Phen as copper chelators endowed with nuclease and cytostatic activities (see above), we prepared a series of chelators using two 8-hydroxyquinoline motifs covalently linked at their C2 position. Contrary to mono(8-hydroxy)quinolines, bis(8-hydroxy)quinolines (Figure 3) offer tetradentate N2O2 binding sites to form copper complexes with a ligand/metal ratio = 1:1. The affinity of bis(8-hydroxyquinolines) for Cu(II) is higher than that of mono(8-hydroxy)quinolines by 4 to 6 orders of magnitude, with logKapp of 15.5–16.6 at physiological pH [57, 58]. However, their selectivity for copper with respect to zinc is only 100 to 1000 [logKapp for Zn(II) = 12.5–14.2]. These ligands are efficient at solubilizing Aβ peptides and are able to inhibit H2O2 production by the Cu–Aβ/ascorbic acid system. These results were superior to those obtained with the corresponding 8-hydroxyquinoline monomers, thus validating the strategy of tetradentate chelators. However, their affinity for Zn(II) is still too high to consider these ligands as biologically pertinent copper regulators [59].

4.3. Bis(8-aminoquinolines)

To proceed to the transfer of copper from Aβ to glutathione (an efficient copper carrier) and, therefore, to restore the copper homeostasis in AD brains, we designed a series of tetradentate ligands L based on a bis(8-aminoquinoline) scaffold, which are specific for copper coordination (Figure 4, PA1637, 1, 2) [11]. These ligands have a high affinity for Cu(II) ions, with log Kapp values ranging from 14 to 16 at pH 7.4, and a low affinity for Zn(II), resulting in very high selectivity for Cu(II) with respect to Zn(II), with a log [Kapp(Cu–L)/Kapp(Zn–L)] value over 12 [60]. In vitro, at micromolar concentrations, they efficiently extract Cu(II) from Cu(II)–Aβ, to provide the Cu(II)–L complex (Scheme 2) [54]. The presence of an amino function at the C8-position of the quinoline skeleton is required for the specific chelation of copper.

Transfer of copper from Cu–Aβ to Cu-proteins, assisted by a specific Cu(II) chelator. L stands for TDMQ20; GSH stands for glutathione. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [41]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

Importantly, this series of chelators offers a well-defined square planar coordination suitable for Cu(II) but not for Cu(I). So, in the presence of glutathione (GSH), a reducing agent and a competitive ligand for copper, the Cu(II)–L complex readily releases its copper ion to glutathione to generate a Cu–GSH complex that will be able to transfer copper to regular metal carriers (Scheme 2) [61].

In such conditions, the bis(8-AQ) ligand is released and should be able to act as a catalyst (Scheme 2). Bis(8-AQ) ligands may therefore be considered as suitable copper regulators of the copper homeostasis. Conversely, it was also shown that the copper complex of the mono(8-hydroxyquinoline) derivative PBT2 was unable to release copper in the presence of GSH.

On the basis of these in vitro studies, the pharmacological activity of PA1637 (Figure 4) was evaluated on a murine model of AD. The preclinical evaluation of drug candidates against AD has usually been carried out on transgenic mice [48, 62, 63]. However, AD is not a condition determined by a single gene mutation but a multi-parameter pathology in which a large number of age-related genes are involved. The fact that these transgenic mouse models do not accurately reflect human pathogenesis is probably one of the reasons for the failures during preclinical selection of drug candidates [64, 65]. To enlarge the panel of predictable mice models, we developed a non-transgenic mouse model of AD. In regular mice (much cheaper than transgenic ones), a memory impairment similar to the early stage of AD is triggered by a single injection of Aβ1–42 oligomers in the mouse cerebral lateral ventricles (intracerebroventricular [icv] model) [66]. The animal model is validated by the fact that injection of the control antisense peptide Aβ42–1 has no effect on mouse memory and behavior. The ability of PA1637 to inhibit the episodic memory loss was evaluated on this non-transgenic murine model. After a short oral treatment with PA1637 (8 doses of PA1637, 25 mg/kg each, over a 3-week period), the episodic memory of AD mice was completely restored, similar to that of healthy animals, while that of untreated AD mice was significantly impaired [66]. These results clearly validated the oral administration of PA1637 to fully inhibit the cognitive impairment induced by icv injection of amyloid oligomers, a way to mimic the early stage of AD. At the moment, there is no treatment able to regenerate functional neurons in the late stages of AD. An efficient drug able to stop the development of AD in the early stages will be welcome.

4.4. Tetradentate mono-8-aminoquinolines (TDMQ) against Alzheimer’s disease

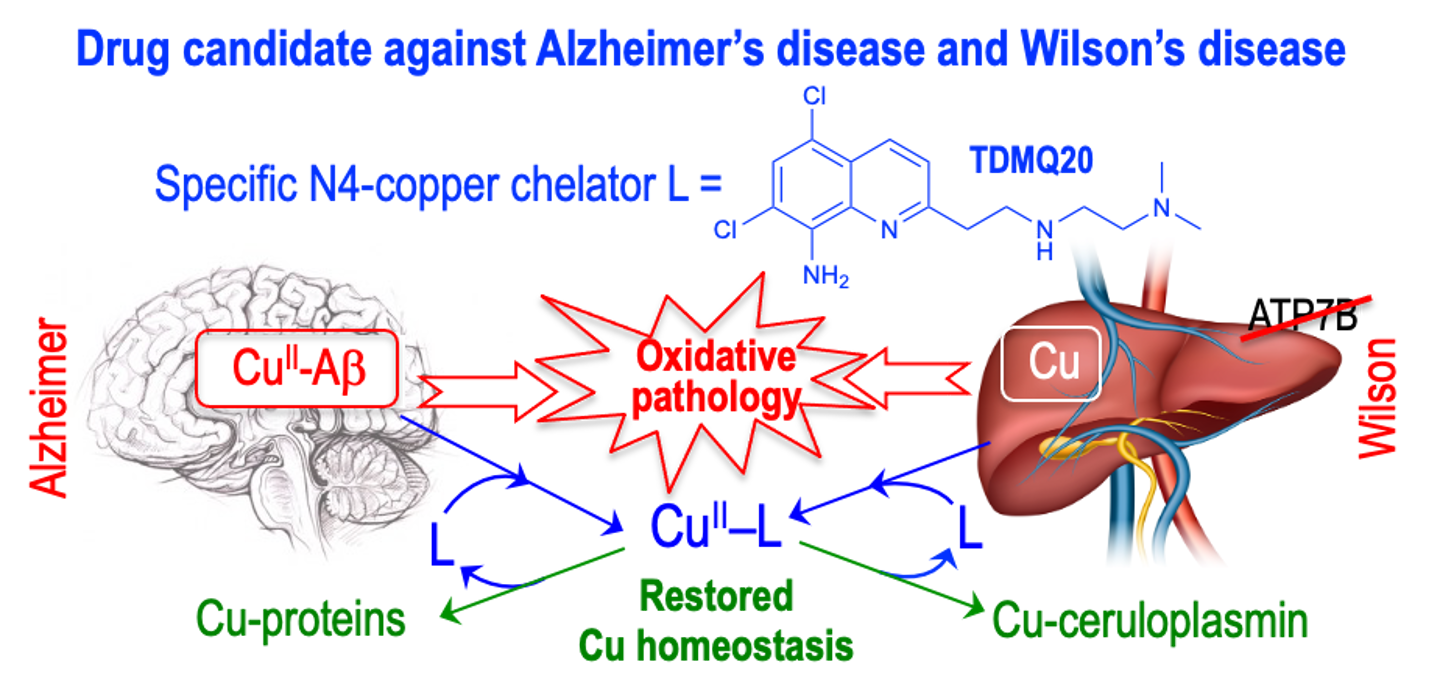

In spite of the capacity of PA1637 to extract copper from copper–amyloid in vitro and to inhibit the catalytic production of H2O2 by Cu(II)–amyloid, its development was stopped due to its rather low bioavailability. To enhance the efficiency and druggability of such copper chelators, a new series of tetradentate amine ligands (named TDMQs) was designed. TDMQs were based on a mono(8-amino)quinoline motif substituted at the C2 position by a nitrogen-containing side chain, able to offer a N4-tetradentate square planar coordination site for Cu(II) complexes, similar to that of bis(8-AQ) (Figure 4) [67, 68]. Structural modulation of the polyamine chain allowed tuning the geometry of the coordination site and, consequently, the copper selectivity and the ability to inhibit oxidative stress.

In this TDMQ series, the ligands having a side chain with n = m = 2 (2 + 2 methylene groups), exhibited the highest affinity values for Cu(II), with log Kapp [Cu–L] values in the range 15–17, and also the highest selectivity for Cu(II) with respect to Zn(II) (ratio > 11 log units) [68]. These chelators were also able to transfer copper from Cu–Aβ to glutathione, and to inhibit the aerobic production of ROS induced by Cu–Aβ in the presence of a reductant [56]. These features are clearly related to the capacity of these N4-tetradentate ligands to offer a tetradentate square planar coordination sphere around the copper(II) ion, generating copper complexes with four nitrogen ligands in a N4 equatorial plane coordination sphere [69]. Noteworthily, bis(8-AQ) derivatives (structures depicted in Figure 4) offered the same coordination, resulting in similar correlations between the structures of the Cu(II)–L complexes and their physicochemical properties such as high affinity for Cu(II) and ability to inhibit ROS production [60].

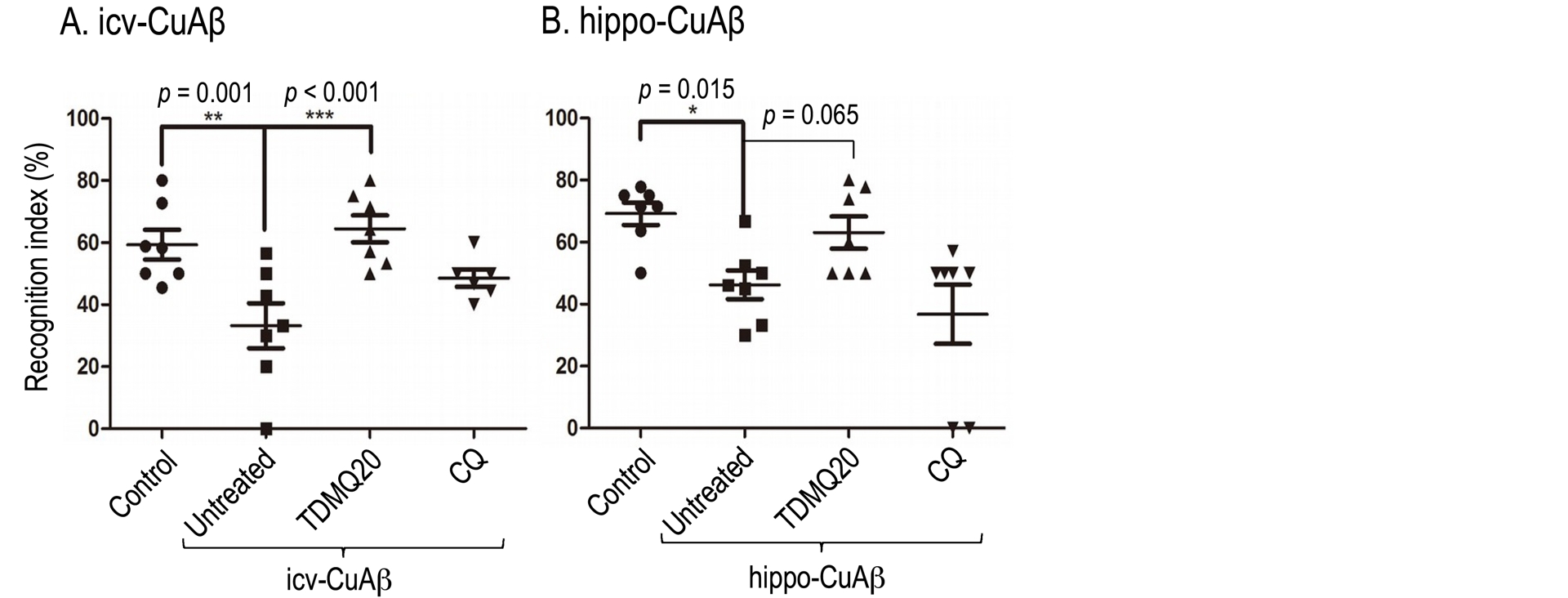

Based on these results, TDMQ20 (Figure 4) was selected for evaluation of its anti-AD activity on three different mouse models. An oral treatment with TDMQ20 was used to check the possibility of reversing the cognitive and behavior impairments in two non-transgenic models mimicking the early stage of AD and in a transgenic one modeling a more advanced stage of AD. In the non-transgenic mice, memory deficits were triggered by a single injection of the copper complex of amyloid Aβ1–42 in the lateral ventricles (icv-CuAβ model) or hippocampus (hippo-CuAβ model) of regular mice. The third model was the classical transgenic mouse 5XFAD model [70, 71].

A short oral treatment with TDMQ20 of icv-CuAβ or hippo-CuAβ mice (10 mg/kg, 8 doses over 16 days) fully restored the cognitive status evaluated by the short-term novel object recognition (NOR) assay [72], in comparison to untreated AD mice (Figure 5) [73].

Declarative memory evaluated by the short-term novel object recognition task (NOR). The recognition index for short term memory in the icv-CuAβ and the hippo-CuAβ non-transgenic mouse models are reported in panels A and B, respectively. In each case, the recognition index of AD mice which received no drug-treatment (untreated group) was compared to that of healthy mice (control group), and to the recognition index of AD mice treated with TDMQ20 or clioquinol (CQ) (8 × 10 mg/kg in 16 days). Each mark represents the result obtained with a single mouse; horizontal lines represent mean values ± SEM. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05 vs. the untreated AD group (ANOVA). Adapted with permission from Figure 2 of Ref. [73]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

By comparison, the 8-hydroxyquinoline derivative clioquinol (CQ) did not significantly improved the short-term memory of icv-CuAβ- and hippo-CuAβ mice. The level of malondialdehyde, the signature of an oxidative stress, in the cortex of icv-CuAβ was also reduced by TDMQ20. The three-month oral treatment of transgenic 5XFAD mice with TDMQ20 also resulted in behavioral improvements. Pharmacokinetic studies in rats indicated that TDMQ20 has a good bioavailability and efficiently crosses the blood–brain barrier after oral administration [74]. Noteworthily, TDMQ20 did not exhibit significant acute or chronic toxicity [73].

In addition, a three-month oral treatment of 5XFAD mice with TDMQ20 remarkably reduced the plaque loading in the cortex by about 70%, suggesting a beneficial role of TDMQ20 in clearing pathological Aβ deposits in AD mice. The treatment also significantly increased the expression of the ChAT enzyme and the CHRM4 receptor, two proteins involved in the cholinergic system [75]. All these results strongly suggest that TDMQ20 is acting on several pathways of this multifactorial disease.

Due to their reliability and easy use, the icv-CuAβ and hippo-CuAβ mice should be considered as robust non-transgenic models to evaluate the activity of potential drugs in the early stages of memory deficits. Moreover, among other possible assays [76, 77], the short-term NOR test was found particularly robust to evaluate the impairment of declarative memory in mice, making it easy to select molecules for the treatment of the early stages of AD.

One should keep in mind that the few current AD therapies are not curative and provide at best a short-term improvement in symptoms, with potentially serious side effects. Moreover, their efficiency/cost ratios are questionable. Despite intensive efforts on AD over the last two decades in genetics, biochemistry, and cell biology, the pipeline of new drugs is rather unproductive. As a reference point, lecanemab, approved in the United States for the treatment of AD, is an anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody administered intravenously every other week with a post-infusion observation period with monitoring of the effect by magnetic resonance imaging. In addition to these rather strong constraints, treatment with lecanemab results in frequent and potentially severe anticoagulation side effects, and this treatment is not recommended for patients with a wide range of comorbidities, a very frequent condition in aging patients [78]. In addition, the European health agency (EMA) initially refused this treatment (July 2024) [79]. Donanemab, another antibody targeting amyloids recently approved by the FDA (June 2024), also induces fatal brain bleeding in a few patients [80]. These facts strongly suggest that efforts should be made to support the discovery of new “small molecules”, namely chemical agents, designed for an easy crossing of the blood–brain barrier in order to produce an efficient pharmacological effect on the early stages of AD, without strong constraints or potentially severe adverse effects.

So the efficacy of TDMQ20 by oral administration at low doses on three different AD mouse models with a very low toxicity, is an encouragement for a future development of this specific copper chelator, maybe in parallel with research of other molecules targeting different mechanisms. However, considering that the introduction of a new drug candidate in the pipeline of AD treatments is rather challenging, we decided to investigate the correlation between the copper chelating activity of TDMQ20 and its therapeutic interest in a well-known copper-related disease, namely the Wilson’s disease.

5. Tetradentate mono-8-aminoquinoline TDMQ20 and Wilson’s disease

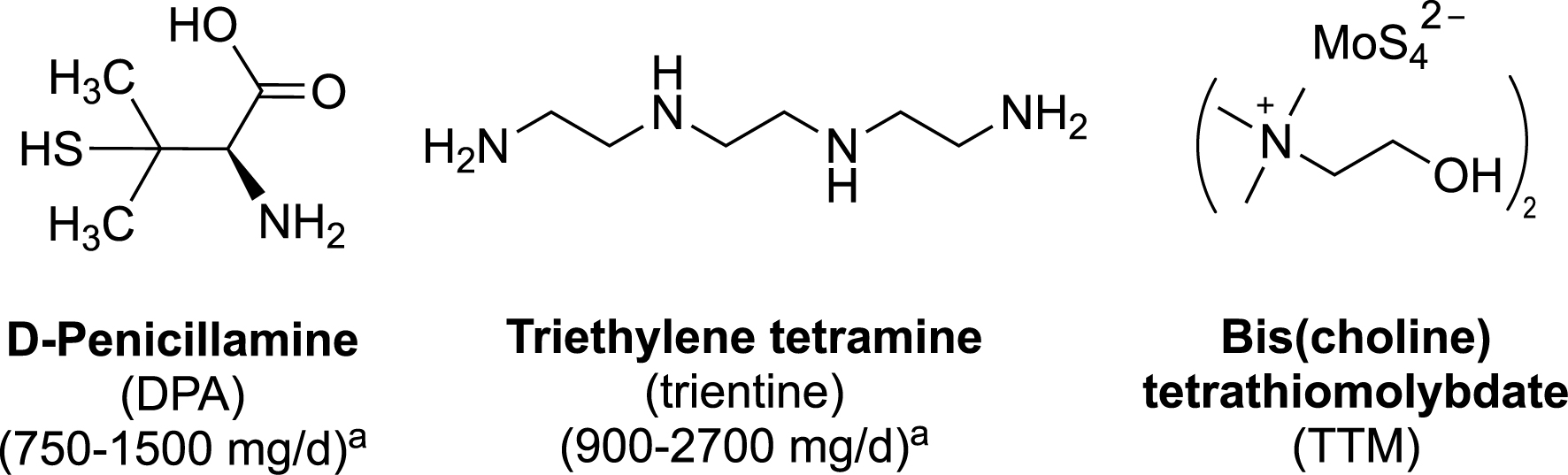

Wilson’s disease (WD) is a genetic disease caused by mutations on the Atp7b gene coding for the copper carrier ATP7B, an ATPase in charge of incorporating copper in apoceruloplasmin in the liver, leading to the elimination of this metal ion in bile and then in feces. Deficiency in this copper carrier causes accumulation of copper in the liver, generating acute or chronic hepatitis and liver cirrhosis, potentially leading to a fulminant hepatic failure. Copper is partially released in the bloodstream and slowly eliminated in urine. In advanced stages of the disease, neurological symptoms such as seizures or Parkinsonism appear, along with psychiatric disorders. Accumulation of copper in various organs, resulting especially in renal and cardiac pathologies as well as hypoparathyroidism and osteoarticular damages, are correlated with a fatal prognosis [17, 18]. Lifelong treatment is therefore necessary, using copper chelators to facilitate the excretion of copper. The first-line drugs for WD treatment via oral administration are currently D-penicillamine (DPA) and, to a lesser extent, trientine, a non-selective polyamine chelator (Figure 6) [81].

Structures of copper chelators currently used in the treatment of Wilson’s disease (DPA and trientine), or in development (TTM). a Daily oral dosage for an adult [82].

These two drugs are given at very high doses (1–2 g per day for an adult) and exhibit adverse effects that may be serious enough to require discontinuation of the treatment (in approximately 30% of patients for DPA) [82, 83]. The efficacy of DPA in neurologic WD is only moderate (55% of improvement rate), and both DPA and trientine induce a severe and irreversible neurological worsening in 10–50% of patients with previous neurological symptoms [84]. So there is a real medical need for a specific copper chelator able to efficiently regulate the copper excess, at lower doses than those used for DPA or trientine and with lower side effects in the long term. Ammonium tetrathiomolybdate has been proposed for more than 30 years [85], recently replaced by bis-choline tetrathiomolybdate (TTM, Figure 6) [86]. The $\mathrm{MoS}_{4}^{2-}$ ion chelates copper to form very stable and highly insoluble sulfur-bridged Mo–Cu clusters [87, 88] detected in the liver of WD rat models [87], resulting in accumulation of molybdenum in major organs (spleen, liver, adrenal glands, kidney, and brain) following administration of TTM [89, 90]. The high affinity of TTM for copper is also responsible for inhibition of major copper enzymes such as ceruloplasmin, ascorbate oxidase, cytochrome oxidase, Cu/Zn-superoxide dismutase and tyrosinase [91].

The main drawback of DPA and trientine as ligands is their lack of selectivity in metal chelation. In fact, both drugs coordinate with high affinities a wide variety of metal ions and oxidation states [92] (see footnote1 ). For example, DPA coordinates Cu2+ with logK1 = 16.5, but also Cu+ (logK1 = 19.5), Zn2+ (logK1 = 9.6 and logβ2 = 19.6) [92], as well as Fe2+, Fe3+, Co2+, and Co3+ [93]. In addition, the structures of DPA–metal complexes can be diverse, including ternary complexes involving another amino acid such as histidine or methionine [94, 95], or mixed valence Cu(I)/Cu(II) cluster complexes [96]. Moreover, the ability of DPA to act as a reductant due to its thiol functionality, in addition to its capacity to coordinate both Cu(II) and Cu(I) [or Fe(III) and Fe(II)], may confer to DPA complexes the ability to trigger deleterious Fenton-like reaction damages.

Due to the specificity of TDMQ20 for chelation of Cu(II) and the oral bioavailability of this ligand , we decided to evaluate its activity for the treatment of WD. In TX mice, a genetic model of WD [97], the overload of copper in the liver was reduced in a dose-dependent manner by a short oral treatment with TDMQ20 at doses ranging from 12.5 to 50 mg/kg/day (Figure 7a). This decrease in hepatic copper was correlated to an increase in fecal copper excretion (Figure 7b) [98]. These studies indicate that such low doses of TDMQ20 are more efficient at improving the physiological excretion pathway of copper in TX mice than DPA at 200 mg/kg/day. TDMQ20 also increases the serum concentration of ceruloplasmin (Figure 7c). Such an effect is particularly important since this concentration is a biomarker clinically used to evaluate the efficency of chelation therapy in patients with WD.

Concentration of copper in liver (a) and feces (b) in mg/kg, and of ceruloplasmin in serum (c) of TX mice (WD) after oral treatment with TDMQ20 at 12.5 mg/kg/d (TDMQ20-L), 25 mg/kg/d (TDMQ20-M), or 50 mg/kg/d (TDMQ20-H). WD mice orally treated by DPA at 200 mg/kg/d are given for comparison. Control mice are healthy C57BL/6 mice bearing no mutation on ATP7B. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 and ****p < 0.0001. Adapted from Ref. [98].

In addition, TDMQ20 up to 300 μM does not disturb the activity of Cu/Zn-SOD, in contrast with DPA, which inhibits Cu/Zn-SOD at a 50 μM concentration. In addition, the DPA–copper complex produces damaging ROS in vitro in the presence of a reducing agent, which is not the case with TDMQ20. In fact, DPA inhibits catalase in vitro and could be responsible for chronic inflammation through chronic disruption of H2O2 redox homeostasis in vivo [99]. In conclusion, TDMQ20 should be considered as a first-in-class drug candidate able to challenge DPA in the treatment of WD.

6. TDMQ20 copper chelator as anticancer agent

The possibility of using metal ligands in anticancer chemotherapy to regulate metal homeostasis has not been extensively explored, although it is known that the metal ion content is significantly higher in cancer cells compared to normal ones [100]. In particular, copper ions are involved in angiogenesis [101, 102], which is essential for tumor growth and dissemination of cancer metastases [103, 104]. It has been evidenced that copper depletion inhibits angiogenesis in cancer cells [105]. A few clinical trials have been reported with copper chelators such as DPA, trientine, or TTM, three ligands that have been documented for WD (see above, Figure 6). However, these attempts have not been successful, probably due to their lack of metal selectivity and/or potential toxicity [106]. So having TDMQ20 at hand as specific copper chelator, preliminary evaluation of its activity against different cancer cell lines was carried out. TDMQ20 was found cytotoxic against non-small cell lung carcinoma (A549), cervix cancer HeLa and hepatocarcinoma HepG2 cells, with IC50 values ranging from 14 to 16 μM in vitro, lower than the reference drug 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU), and the selectivity index of TDMQ20 was higher than that of 5-FU when using non-cancer human cells as comparators. TDMQ20 also exhibited a significant anti-migration activity on HeLa cells in vitro. Mechanistic studies indicated that the activity of TDMQ20 probably involves the overproduction of ROS, with the collapse of the inner transmembrane potential in mitochondria and the induction of apoptosis [107].

7. Conclusion

Since copper plays essential functions in human body, this metal ion can be considered as a promising therapeutic target in several diseases. A twenty-five-year review of the state of the art in rational chelator design has led us from phenanthroline derivatives to the N4-tetradentate mono-8-aminoquinoline series, especially the TDMQ20 as a suitable copper(II) chelator for therapeutic use. Due to its optimized coordination properties, this specific Cu(II) ligand exhibits a promising activity on murine models of Alzheimer’s and Wilson’s diseases, two diseases involving copper dyshomeostasis and copper accumulation, respectively. Clinical development of TDMQ20 as a therapeutic alternative to DPA for normalizing copper levels in WD patients is currently under discussion. In addition, this chelator is more active than the reference drug 5-FU on several human cancer cell lines. Future clinical developments will be necessary to evidence which therapeutic domain will be best tackled by TDMQ20.

As a concluding remark, the specificity for copper chelation and the structure and properties of the corresponding copper complex are prerequesite parameters in the design of pharmacological ligands suitable for targeting diseases triggered by the pathological disruption of copper homeostasis.

Data availability

All data presented in this review article have been reported in the cited articles of our group and in the associated supporting information.

Acknowledgments

Authors gratefully acknowledge all colleagues, postdoctoral fellows, PhD and master students, and collaborators who have been involved in the research of specific metal regulators as potential drugs.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

Financial support was received from the CNRS, Inserm, and GDUT.

1

| \begin{eqnarray*} &\displaystyle \mathrm{M} + \mathrm{L} \mathop{\rightleftharpoons}\limits_{K_1} \mathrm{ML} \mathop{\rightleftharpoons}\limits_{K_2}^{\mathrm{L}} \mathrm{ML}_2 \\\\ &\displaystyle K_1=\frac{[\mathrm{ML}]}{[\mathrm{M}][\mathrm{L}]} \quad K_2=\frac{[\mathrm{ML}_2]}{[\mathrm{ML}][\mathrm{L}]}\quad \beta_{1,2}=\frac{[\mathrm{ML}_2]}{[\mathrm{M}][\mathrm{L}]^2} =K_1 K_2 \\&\displaystyle \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \qquad (\mbox{usually noted } \beta_{2}) \end{eqnarray*} |

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0