1. Introduction

Catalysts for ethylene polymerization based on late transition metals have been widely documented since their inception in the mid to late 1990s on account of their exceptional catalytic performance [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39]. Since these pioneering disclosures, there has been rapid progress in the use of the 2,6-bis(imino)pyridine ligand (A, Chart 1) as a chelating support for both iron and cobalt catalysts, driven by the desire for ever higher activity as well as improvements in thermal stability; recent progress has been reviewed [40, 41]. Besides their excellent performance characteristics, such late transition metal catalysts also produce linear polyethylene with a broad range of structural properties that can be modulated by the specifics of the ligand structure [42, 43, 44, 45, 46]. Indeed, the resulting polymers offer promise for applications in a variety of fields, such as automobiles, pipes, and so on.

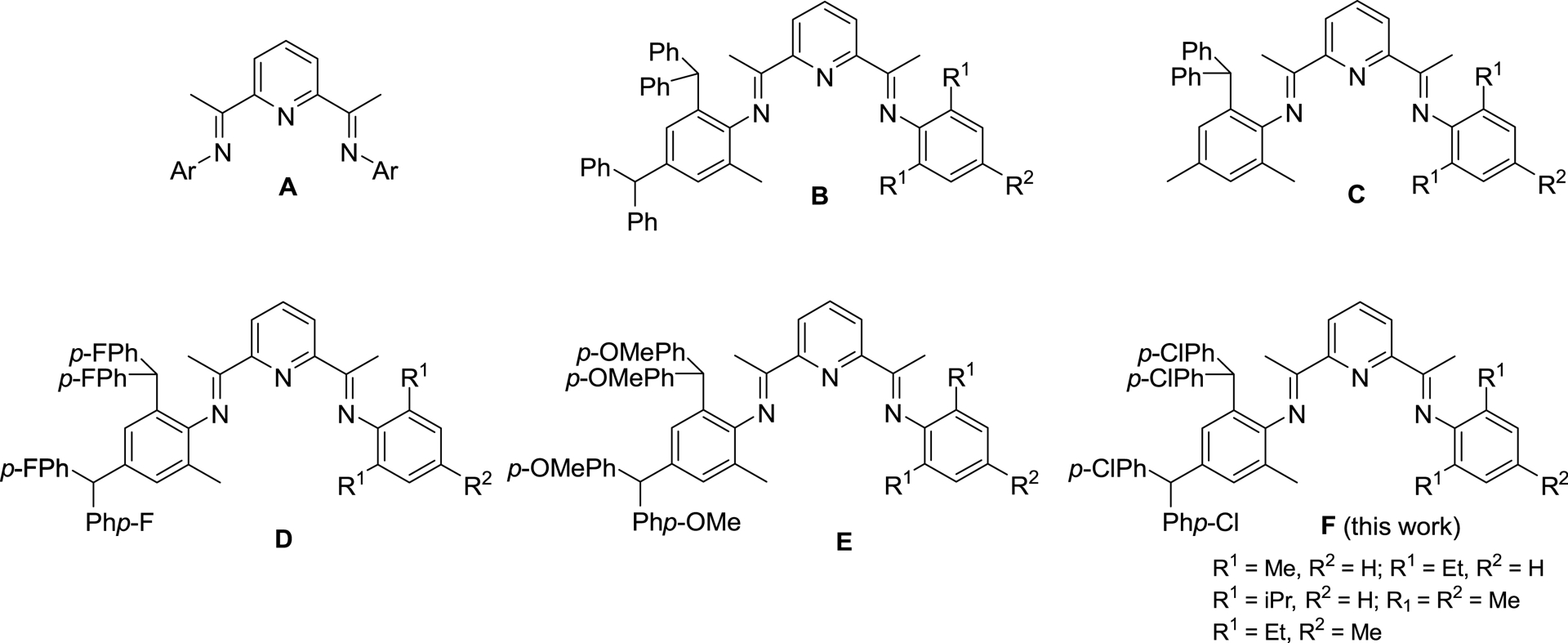

Parent 2,6-bis(arylimino)pyridine (A) and its unsymmetrical derivatives (B–E) incorporating various types of benzhydryl substitution including the subject of this work (F).

In recent years, our group has been interested in designing new bis(arylimino)pyridyl–iron and –cobalt catalysts by systematically varying the types of N-aryl groups [47, 48, 49, 50]. Of note, unsymmetrical examples incorporating bulky benzhydryl substitution have emerged including 2,4-dibenzhydryl-6-methylphenyl (B, Chart 1) [47], 2-benzhydryl-4,6-dimethylphenyl (C, Chart 1) [48], 2,4-bis(bis(4-fluorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylphenyl (D, Chart 1) [49] and 2,4-bis(bis(4-methoxyphenyl)methyl)-6-methylphenyl (E, Chart 1) [50]. A notable outcome of these studies is that the ortho-benzhydryl substituent can provide protection to the active center and improve thermal stability of the catalyst. Furthermore, the electronic variations made to the periphery of the benzhydryl group (viz., para-X = H, F, OMe) can further influence this stability and also affect catalytic activity and various polymer properties.

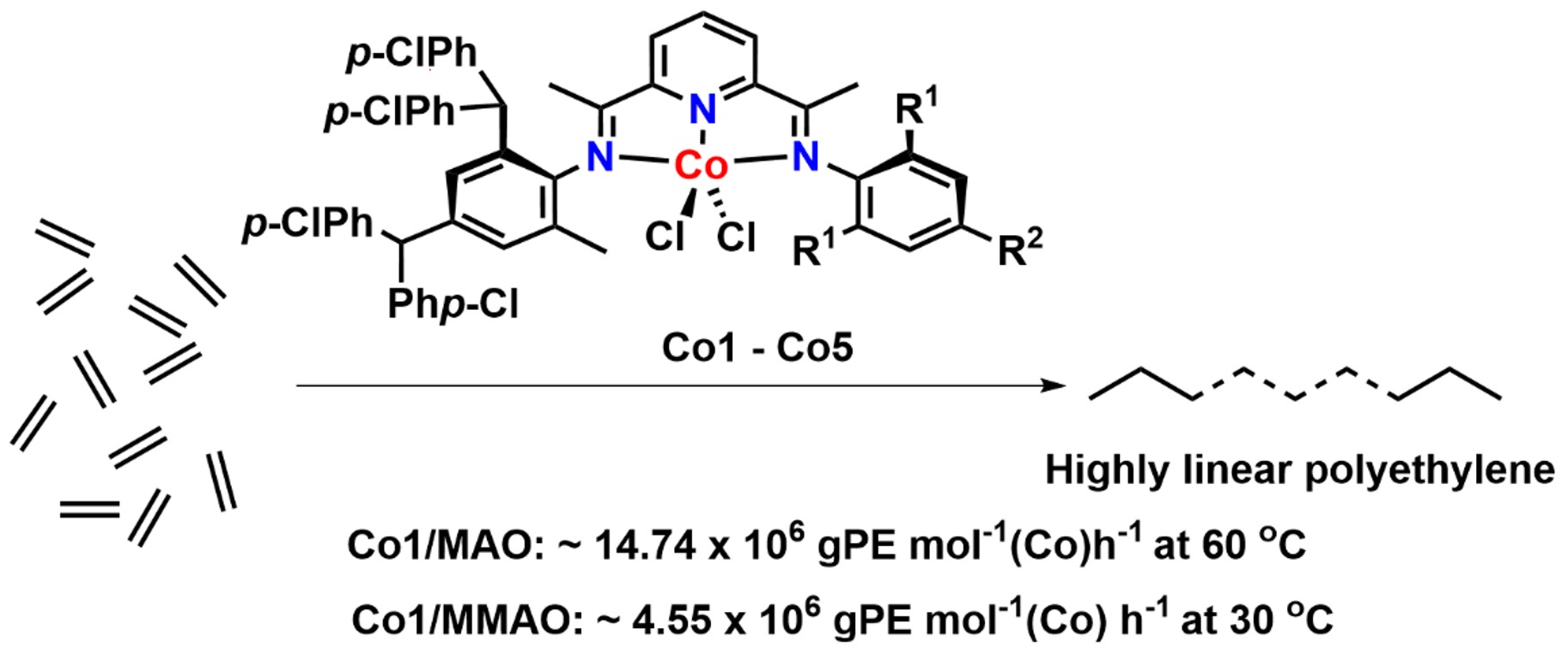

With the intention of further probing the impact of the benzhydryl’s para-X group on catalyst activity and polymer properties, we herein focus on the para-Cl derivative F (Chart 1) as a support for a cobalt polymerization catalyst. Accordingly, the synthetic details for a family of F are given that encompass a range of steric and electronic variations made to one of the N-aryl groups. This set of unsymmetrical N′,N,N′′-ligands are then used to prepare their cobalt(II) chloride complexes, which are then applied in a comprehensive ethylene polymerization evaluation. The findings of this evaluation are then compared to those reported for cobalt catalysts bearing B–E (Chart 1), with the aim of highlighting any effects of the para-Cl substitution on catalytic activity, thermal stability, polymer molecular weight, and dispersity. Full synthetic and characterization data for the complexes, ligands, and polyethylenes are reported.

2. Experimental

2.1. General considerations

Standard Schlenk techniques were used in the handling of air- and moisture-sensitive compounds and were conducted under an inert nitrogen atmosphere. Immediately before the polymerization evaluations were conducted, the reaction solvent, toluene, was heated to reflux over sodium and then distilled under nitrogen. High-purity ethylene gas was purchased from Beijing Yansan Petrochemical Co. and used as received. The activators methylaluminoxane (MAO, 1.30 M solution in toluene) and modified methylaluminoxane (MMAO, 1.93 M in n-heptane) were purchased from Anhui Botai Electronic Materials Co. Other reagents were purchased from Aldrich, Acros, or local suppliers (Beijing, China). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of the organic compounds were recorded on a Bruker DMX 400 MHz instrument at room temperature with TMS as internal standard; chemical shifts are measured in ppm. Elemental analysis was recorded on a Flash EA 1112 microanalyzer and FT-IR spectra on a System 2000 FT-IR spectrometer. An Agilent PL-GPC 220 GPC instrument was used to determine the molecular weight (Mw) and molecular weight distribution (Mw/Mn) of the resulting polyethylene at 150 °C by using 1,2,4-trichlorobenzene as the eluting solvent. The melting temperatures (Tm) of the polyethylenes were recorded on a PerkinElmer TA-Q2000 differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) under a nitrogen atmosphere. Typically, a sample of about 3.0–5.0 mg was heated up to 160 °C at a rate of 20 °C⋅min−1, kept for 2 min at 160 °C to delete the thermal history and then cooled at a rate of 20 °C⋅min−1 to −40 °C. The 13C NMR spectra of the polyethylenes were recorded on a Bruker DMX 500 MHz instrument at 100 °C; sample preparation involved a weighed amount of polyethylene (30–50 mg) being dissolved in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d2 with TMS as an internal standard. The imine-ketones, 1-(6-(1-(arylimino)ethyl)pyridin-2-yl)ethan-1-ones (aryl = 2,6-dimethylphenyl; 2,6-diethylphenyl; 2,6-diisopropylphenyl; 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl; 2,6-diethyl-4-methylphenyl) and 2,4-bis(bis(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylaniline were prepared as previously described [51, 52].

2.2. Syntheses of 2-{{2,4-((p-ClPh)2CH)2-6-MeC6H2}N=CMe}-6-(ArN=CMe)C5H3N (L1–L5)

2.2.1. Ar: 2,6-Me2C6H3 (L1)

A catalytic amount of p-toluenesulfonic acid was added to a solution of 1-(6-(1-((2,6-dimethylphenyl)imino)ethyl) pyridin-2-yl)ethan-1-one (2.54 g, 9.53 mmol) and 2,4-bis(bis(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylaniline (5.00 g, 8.66 mmol) in toluene (30 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred and heated under reflux for 9 h. Once cooled to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered and all volatile components removed on a rotary evaporator. The remaining solid was loaded onto a basic alumina column and eluted with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (v/v = 500/1) to afford L1 as a pale-yellow solid (2.53 g, 35%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 8.48 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.90 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 7.16 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 7.11–7.08 (m, 4H, Ph-H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 6.94 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, Ph-H), 6.38 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 5.35 (s, 1H, –CH–), 5.33 (s, 1H, –CH–), 2.18 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.09 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.04 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.96 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.69 (s, 3H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 168.9, 167.1, 155.3, 154.8, 148.7, 146.8, 142.3, 142.2, 141.3, 140.7, 137.4, 136.8, 132.5, 132.4, 132.4, 132.2, 130.9, 130.6, 130.5, 130.5, 130.5, 129.6, 128.5, 128.3, 128.3, 128.3, 128.0, 127.9, 125.7, 125.4, 123.1, 122.3, 122.0, 55.0, 51.1, 18.0, 17.9, 16.8, 16.4. FT-IR (cm−1): 2917 (w), 1900 (w), 1642 (𝜈C=N, m), 1594 (w), 1570 (w), 1489 (s), 1466 (m), 1404 (m), 1363 (m), 1297 (w), 1238 (m), 1209 (m), 1121 (m), 1090 (s), 1015 (m), 825 (m), 795 (m), 761 (m), 685 (m). HRMS (MALDI-TOF) m/z: [M]− Calcd for C50H41Cl4N3 823.2049, Found 823.2043. Anal. Calc. for C50H41Cl4N3 (825.70): C, 72.73; H, 5.01; N, 5.09%, Found: C, 72.23; H, 4.94; N, 4.96%.

2.2.2. Ar: 2,6-Et2C6H3 (L2)

Using a method and molar ratios of reagents similar to those described for L1, L2 was isolated as a pale-yellow powder (0.36 g, 10%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 8.46 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.90 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, Ph-H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 7.05 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 6.97 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 5H, Ph-H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, Ph-H), 6.40 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 5.36 (s, 1H, –CH–), 5.35 (s, 1H, –CH–), 2.47–2.35 (m, 4H, –CH2–), 2.21 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.97 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.71 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.20 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, –CH3), 1.15 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 169.0, 166.9, 155.3, 154.8, 147.8, 146.8, 142.3, 142.2, 141.3, 140.7, 137.4, 136.8, 132.5, 132.3, 132.2, 131.2, 130.9, 130.5, 130.5, 129.6, 128.5, 128.5, 128.3, 128.3, 126.0, 125.7, 123.4, 122.3, 122.0, 55.0, 51.1, 24.6, 17.9, 16.8, 13.7. FT-IR (cm−1): 2964 (w), 1899 (w), 1640 (𝜈C=N, m), 1568 (w), 1489 (s), 1452 (m), 1404 (m), 1362 (m), 1296 (w), 1235 (m), 1205 (m), 1120 (m), 1090 (s), 1016 (m), 961 (w), 879 (w), 823 (s), 795 (s), 762 (m), 703 (m), 681 (m). HRMS (MALDI-TOF) m/z: [M]− Calcd for C52H45Cl4N3 851.2362, Found 851.2363. Anal. Calc. for C52H45Cl4N3 (853.75): C, 73.16; H, 5.31; N, 4.92%, Found: C, 72.85; H, 5.33; N, 4.71%.

2.2.3. Ar: 2,6-iPr2C6H3 (L3)

Using a method and molar ratios of reagents similar to those described for L1, L3 was isolated as a pale-yellow powder (0.45 g, 15%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 8.46 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 8.30 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.90 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.25–7.09 (m, 13H, Ph-H), 7.04 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 7.00–6.95 (m, 3H, Ph-H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.83 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.43 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 5.39 (s, 1H, –CH–), 5.34 (s, 1H, –CH–), 2.81–2.69 (m, 2H, –CH–), 2.20 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.97 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.71 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.21 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 6H, –CH3), 1.17 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 6H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 170.1, 167.0, 146.4, 145.9, 141.5, 140.7, 136.8, 135.8, 132.3, 132.2, 131.6, 131.0, 130.6, 128.7, 128.6, 128.4, 123.7, 123.0, 122.3, 122.0, 50.9, 28.3, 23.3, 22.9, 21.3, 17.3, 17.1. FT-IR (cm−1): 2960 (w), 1904 (w), 1637 (𝜈C=N, m), 1569 (w), 1489 (s), 1458 (m), 1405 (w), 1364 (m), 1322 (w), 1305 (w), 1237 (m), 1210 (w), 1124 (m), 1090 (s), 1014 (s), 965 (w), 898 (w), 871 (m), 827 (s), 796 (m), 776 (m), 710 (w), 683 (w). HRMS (MALDI-TOF) m/z: [M]− Calcd for C54H49Cl4N3 879.2675, Found 879.2670. Anal. Calc. for C54H49Cl4N3 (881.81): C, 73.55; H, 5.60; N, 4.77%, Found: C, 73.75; H, 5.64; N, 4.73%.

2.2.4. Ar: 2,4,6-Me3C6H2 (L4)

Using a method and molar ratios of reagents similar to those described for L1, L4 was isolated as a pale-yellow powder (1.06 g, 15%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 8.45 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.24 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 7.18–7.15 (m, 2H, Ph-H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H, Ph-H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.81 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, Ph-H), 6.39 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 5.35 (s, 1H, –CH–), 5.34 (s, 1H, –CH–), 2.31 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.18 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.06 (s, 3H, –CH3), 2.01 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.96 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.69 (s, 3H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 169.0, 167.3, 155.4, 154.7, 146.8, 146.2, 142.3, 142.2, 141.3, 140.7, 137.4, 136.8, 132.5, 132.3, 132.3, 132.3, 132.2, 130.9, 130.5, 130.5, 130.5, 129.6, 128.6, 128.6, 128.5, 128.5, 128.3, 128.2, 125.7, 125.2, 122.3, 121.9, 55.0, 51.1, 20.7, 17.9, 17.9, 17.8, 16.8, 16.4. FT-IR (cm−1): 2913 (w), 1897 (w), 1640 (𝜈C=N, m), 1569 (m), 1489 (s), 1403 (m), 1362 (m), 1321 (w), 1239 (w), 1213 (m), 1116 (m), 1088 (s), 1013 (s), 962 (w), 823 (s), 794 (s), 761 (w), 745 (w), 703 (m), 682 (w). HRMS (MALDI-TOF) m/z: [M]− Calcd for C51H43Cl4N3 837.2206, Found 837.2201. Anal. Calc. for C51H43Cl4N3 (839.73): C, 72.95; H, 5.16; N, 5.00%, Found: C, 73.05; H, 5.17; N, 4.90%.

2.2.5. Ar: 2,6-Et2-4-MeC6H2 (L5)

Using a method and molar ratios of reagents similar to those described for L1, L5 was isolated as a pale-yellow powder (0.76 g, 17%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 8.45 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 8.28 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.89 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Py-H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 6H, Ph-H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.98–6.94 (m, 6H, Ph-H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ph-H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, Ph-H), 6.39 (s, 1H, Ph-H), 5.36 (s, 1H, –CH–), 5.34 (s, 1H, –CH–), 2.46–2.28 (m, 7H, –CH2– and –CH3), 2.20 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.97 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.71 (s, 3H, –CH3), 1.18 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, –CH3), 1.13 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, –CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3, TMS): 𝛿 169.0, 167.0, 155.4, 154.7, 146.8, 145.2, 142.3, 142.2, 141.3, 140.7, 137.4, 136.8, 132.5, 132.3, 132.3, 132.2, 131.1, 130.9, 130.5, 130.5, 130.5, 129.6, 128.4, 128.3, 128.2, 126.7, 125.7, 122.3, 121.9, 55.0, 51.1, 24.6, 21.0, 17.9, 16.8, 16.7, 13.9, 13.8. FT-IR (cm−1): 2965 (w), 1899 (w), 1642 (𝜈C=N, m), 1598 (w), 1569 (m), 1489 (s), 1454 (m), 1403 (m), 1365 (m), 1326 (w), 1298 (w), 1257 (m), 1208 (m), 1086 (s), 1013 (s), 865 (m), 823 (m), 795 (s), 745 (m), 709 (w), 681 (w). HRMS (MALDI-TOF) m/z: [M]− Calcd for C53H47Cl4N3 865.2519, Found 865.2513. Anal. Calc. for C53H47Cl4N3 (867.78): C, 73.36; H, 5.46; N, 4.84%, Found: C, 73.07; H, 5.51; N, 4.76%.

2.3. Syntheses of [2-{{2,4-((p-ClPh)2CH)2-6-MeC6H2}N=CMe}-6-(ArN=CMe)C5H3N]CoCl2 (Co1–Co5)

2.3.1. Ar: 2,6-Me2C6H3 (Co1)

Under a nitrogen atmosphere, a Schlenk vessel was loaded with L1 (0.18 g, 0.22 mmol) and CoCl2⋅6H2O (0.047 g, 0.20 mmol) and the contents dissolved in a mixture of freshly distilled dichloromethane (5 mL) and ethanol (10 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 9 h at room temperature after which all volatile components were evaporated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was dissolved in dichloromethane, and diethyl ether was added to induce precipitation. The precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with diethyl ether, and dried to afford Co1 as a brown powder (0.17 g, 91%). FT-IR (cm−1): 2915 (w), 2111 (w), 1623 (𝜈C=N, m), 1589 (m), 1489 (s), 1470 (m), 1439 (w), 1403 (w), 1371 (m), 1261 (m), 1212 (m), 1091(s), 1014 (s), 825 (m), 801 (m), 762 (m), 738 (w), 655 (m). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M–Cl]+ Calcd for C50H41Cl5CoN3 917.1070, Found 917.1070. Anal. Calc. for C50H41Cl6CoN3 (955.53): C, 62.85; H, 4.33; N, 4.40%, Found: C, 62.52; H, 4.30; N, 4.26%.

2.3.2. Ar: 2,6-Et2C6H3 (Co2)

Using a procedure and molar ratios of reagents similar to those outlined for Co1, Co2 was isolated as a brown powder (0.080 g, 97%). FT-IR (cm−1): 2968 (w), 1903 (w), 1623 (𝜈C=N, m), 1584 (m), 1489 (s), 1468 (m), 1446 (m), 1404 (w), 1374 (m), 1319 (w), 1263 (m), 1210 (m), 1134 (w), 1088 (s), 1014 (s), 978 (w), 895 (w), 867 (m), 838 (m), 813 (s), 795 (m), 760 (m), 698 (w), 656 (w). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M–Cl]+ Calcd for C52H45Cl5CoN3 945.1383, Found 945.1387. Anal. Calc. for C52H45Cl6CoN3 (983.59): C, 63.50; H, 4.61; N, 4.27%, Found: C, 63.13; H, 4.59; N, 4.13%.

2.3.3. Ar: 2,6-iPr2C6H3 (Co3)

Using a procedure and molar ratios of reagents similar to those outlined for Co1, Co3 was isolated as a brown powder (0.070 g, 84%). FT-IR (cm−1): 2964 (w), 1619 (𝜈C=N, m), 1584 (m), 1489 (s), 1469 (m), 1442 (m), 1404 (w), 1373 (m), 1322 (w), 1263 (m), 1214 (m), 1182 (w), 1090 (s), 1014 (s), 940 (w), 895 (w), 834 (m), 796 (s), 765 (m), 699 (m), 656 (w). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M–Cl]+ Calcd for C54H49Cl5CoN3 973.1696, Found 973.1693. Anal. Calc. for C54H49Cl6CoN3 (1011.64): C, 64.11; H, 4.88; N, 4.15%, Found: C, 64.03; H, 4.89; N, 4.07%.

2.3.4. Ar: 2,4,6-Me3C6H2 (Co4)

Using a procedure and molar ratios of reagents similar to those outlined for Co1, Co4 was isolated as a brown powder (0.090 g, 87%). FT-IR (cm−1): 2912 (w), 1980 (w), 1618 (𝜈C=N, m), 1585 (m), 1489 (s), 1403 (m), 1372 (m), 1320 (w), 1264 (m), 1225 (m), 1182 (w), 1090 (s), 1014 (s), 893 (w), 839 (m), 806 (m), 763 (m), 738 (m), 654 (w). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M–Cl]+ Calcd for C51H43Cl5CoN3 931.1226, Found 931.1229. Anal. Calc. for C51H43Cl6CoN3 (969.56): C, 63.18; H, 4.47; N, 4.33%, Found: C, 62.78; H, 4.48; N, 4.18%.

2.3.5. Ar: 2,6-Et2-4-MeC6H2 (Co5)

Using a procedure and molar ratios of reagents similar to those outlined for Co1, Co5 was isolated as a brown powder (0.090 g, 87%). FT-IR (cm−1): 2966 (w), 1908 (w), 1622 (𝜈C=N, m), 1587 (m), 1490 (s), 1465 (m), 1404 (m), 1372 (m), 1322 (w), 1265 (m), 1216 (m), 1182 (w), 1090 (s), 1014 (s), 865 (m), 835 (m), 806 (s), 799 (m), 762 (m), 739 (m). HRMS (ESI) m/z: [M–Cl]+ Calcd for C53H47Cl5CoN3 959.1539, Found 959.1540. Anal. Calc. for C53H47Cl6CoN3 (997.61): C, 63.81; H, 4.75; N, 4.21%, Found: C, 63.30; H, 4.72; N, 4.08%.

2.4. Polymerization studies

A 250 mL autoclave, equipped with pressure/temperature control system, mechanical stirrer, and an ethylene cylinder, was employed to conduct the ethylene polymerizations. This autoclave was evacuated and backfilled with nitrogen four times, and then with ethylene gas. The pre-determined amount of cobalt complex (2 μmol) was then added to a dry Schlenk tube (100 mL), which had been evacuated and back-filled with nitrogen three times. Freshly distilled toluene (25 mL) was injected to dissolve the cobalt complex, and the resulting solution transferred quickly to the autoclave. More toluene (25 mL) was injected into the Schlenk tube to dissolve any remaining cobalt complex and added to the previous solution; this was repeated one more time. Once the temperature had reached the required value, the pre-determined amount of activator (MAO or MMAO) was injected into the autoclave with a syringe along with another 25 mL of toluene to take the total volume of solvent to 100 mL. With the ethylene pressure set at 10 atm and the temperature at the pre-identified value (and controlled by circulating water or using a water/ice bath), the reaction was started by stirring at 400 rpm. Once the run time was completed, the reactor was cooled to room temperature, and ethylene pressure vented. The reaction mixture was then quenched using a 5% hydrochloric acid in ethanol solution (100 mL), forming the polyethylene as a white powder. After stirring and washing for 2 h, the polymer was collected using suction filtration and dried in a vacuum oven to a constant weight.

2.5. X-ray crystallographic studies

Single-crystal XRD studies on Co1 and Co2 were carried out using a XtaLAB Synergy-R diffractometer with mirror-monochromatic Cu-K𝛼 radiation (𝜆 = 1.54184 Å) at 170.00 K; the cell parameters were obtained by global refinement of the positions of all attained reflections. Direct methods were used to solve the structures, and these were refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2. All hydrogen atoms were placed in calculated positions. Structural solution and refinement were performed using the Olex2 1.2 package and SHELXTL [53]. The application of PLATON software was used during the structural refinement to squeeze the solvent in the lattice [54]. Details of the crystal data and processing parameters are summarized in Table S1.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Synthesis and characterization

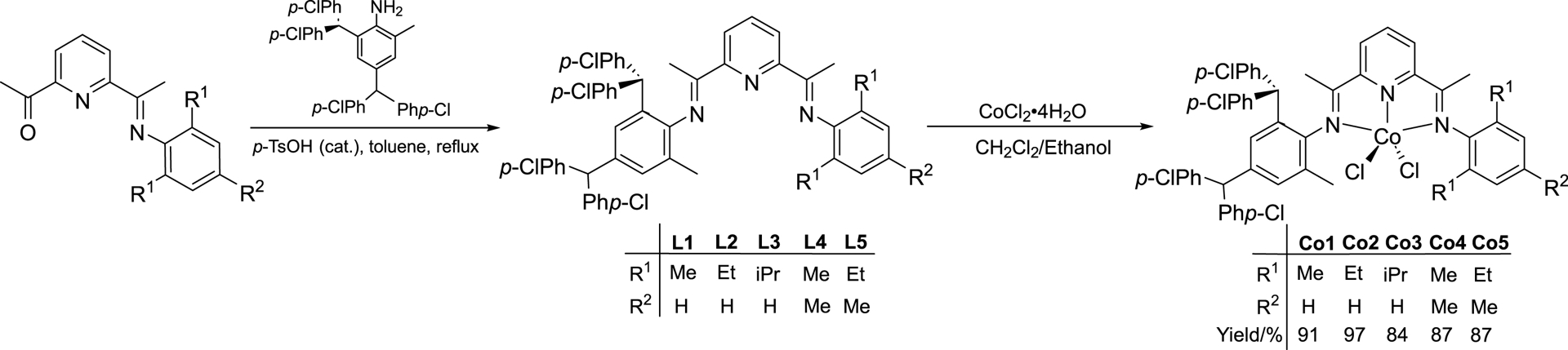

Five different examples of 2-[1-(2,4-bis(di(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylphenylimino)ethyl]-6-[1-(arylimino)ethyl]pyridine (aryl = 2,6-dimethylphenyl (L1); 2,6-diethylphenyl (L2); 2,6-diisopropylphenyl (L3); 2,4,6-trimethylphenyl (L4); 2,6-diethyl-4-methylphenyl (L5)) were synthesized by the acid-catalyzed condensation reaction of the corresponding imine-ketone with 2,4-bis(di(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylaniline in toluene under reflux; related procedures have been reported elsewhere (Scheme 1) [51]. Compounds L1–L5 were isolated in moderate yield and were characterized by 1H/13C NMR and FT-IR spectroscopy, and purity further confirmed by elemental analysis (see experimental).

Synthesis of L1–L5 and their use in forming cobalt(II) chloride complexes Co1–Co5.

Interaction of L1–L5 with CoCl2⋅6H2O in a mixture of ethanol and dichloromethane at room temperature afforded, on work-up, Co1–Co5 in excellent yields (Scheme 1). FT-IR spectroscopy proved an effective means of confirming coordination of the N′,N,N′′-ligands as evidenced by the 𝜈C=N stretching vibrations of Co1–Co5 shifting to lower wavenumbers (range: 1618–1623 cm−1) when compared with the free ligands (range: 1637–1642 cm−1). In their ESI mass spectra, fragmentation peaks corresponding to [M–Cl]+ ions were seen for all five complexes. Additionally, the elemental analysis data were consistent with elemental compositions based on the general formula LCoCl2. Further confirmation of their composition was provided by the X-ray structures of representative Co1 and Co2 (see below).

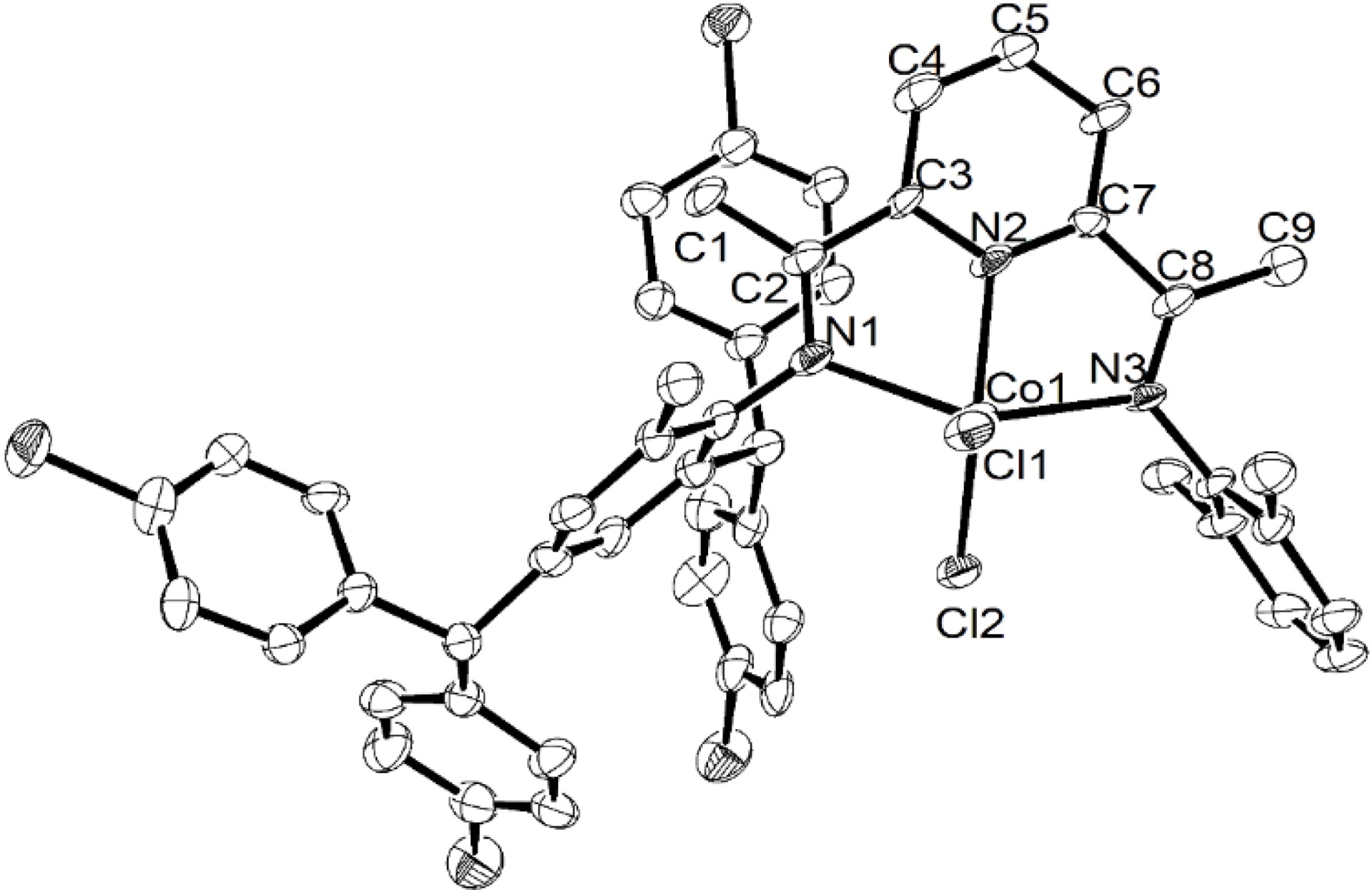

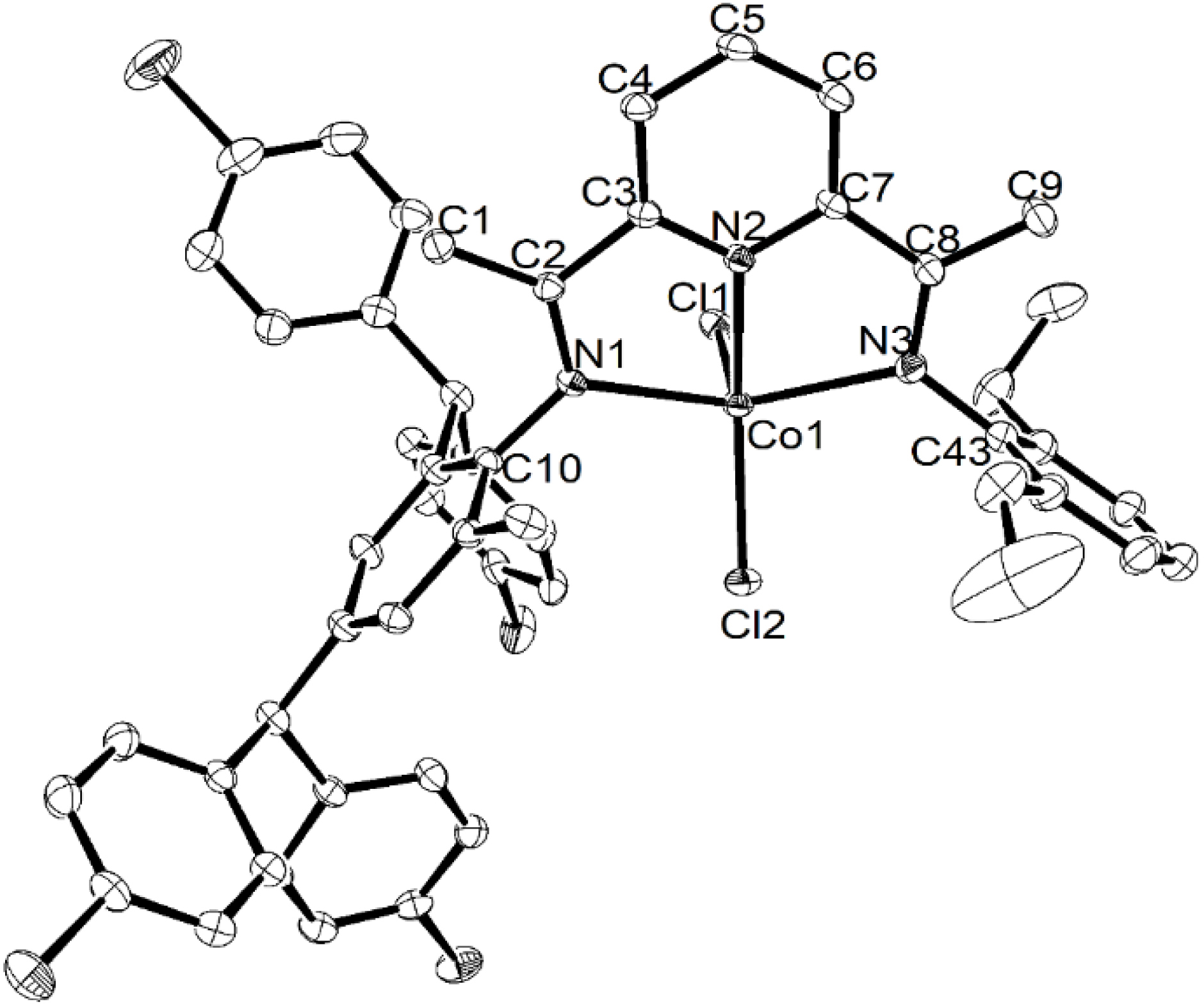

Single crystals of Co1 and Co2 suitable for XRD were obtained by layering a dichloromethane solution of each complex with diethyl ether and leaving the mixture to slowly diffuse at room temperature. Views of Co1 and Co2 are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively; selected bond lengths and angles for both are collected in Table 1. Both complexes Co1 and Co2 are similar and will be discussed together.

ORTEP representation of Co1 with the thermal ellipsoids set at the 30% probability level; all hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

ORTEP representation of Co2 with the thermal ellipsoids set at the 30% probability level; all hydrogen atoms have been removed for clarity.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and angles (°) for Co1 and Co2

| Co1 | Co2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bond lengths (Å) | ||

| Co(1)–N(1) | 2.265(9) | 2.211(3) |

| Co(1)–N(2) | 2.051(8) | 2.050(3) |

| Co(1)–N(3) | 2.195(9) | 2.247(3) |

| Co(1)–Cl(1) | 2.304(3) | 2.3070(10) |

| Co(1)–Cl(2) | 2.249(3) | 2.2464(9) |

| Bond angles (°) | ||

| N(1)–Co(1)–N(2) | 74.4(3) | 74.79(10) |

| N(1)–Co(1)–N(3) | 147.3(3) | 144.68(10) |

| N(2)–Co(1)–N(3) | 75.7(3) | 74.37(11) |

| N(1)–Co(1)–Cl(2) | 98.1(3) | 99.21(7) |

| N(2)–Co(1)–Cl(2) | 141.7(3) | 152.57(9) |

| N(3)–Co(1)–Cl(2) | 97.1(2) | 100.22(8) |

| N(1)–Co(1)–Cl(1) | 96.7(2) | 97.29(7) |

| N(2)–Co(1)–Cl(1) | 103.8(3) | 91.86(8) |

| N(3)–Co(1)–Cl(1) | 103.0(3) | 100.48(8) |

| Cl(2)–Co(1)–Cl(1) | 114.44(11) | 115.54(4) |

In each case, the coordination geometry of the cobalt center can be best described as distorted square pyramidal, with the basal plane defined by N1, N2, N3 and Cl2. The Co1 center sits above the basal plane by 0.571 Å in Co1 and 0.486 Å in Co2, while axial Cl1 further protrudes by 2.853 Å in Co1 and 2.735 Å in Co2. With regard to the Co–N distances, the central Co–Npyridine bond length [2.051(8) (Co1), 2.050(3) (Co2) Å] is markedly shorter than the exterior Co–Nimine ones [2.195(9)–2.265(9) Å], which likely derives from the good donor properties of the central pyridine and the constraints of this N′,N,N′′-ligand class; similar observations have been previously noted [51]. The presence of inequivalent N-aryl groups causes some more modest variations in the exterior Co–Nimine distances, which is also affected by the steric properties exerted by the N-2,6-dimethylphenyl (Co1) and N-2,6-diethylphenyl (Co2) groups. In terms of the Co–Cl bond lengths, some variation is also seen with that involving the axial chloride (Co–Cl1: 2.304(3) Å (Co1), 2.3070(10) Å (Co2)) longer than its basal counterpart (Co1–Cl2: 2.249(3) Å (Co1), 2.2464(9) Å (Co2)). The N-aryl rings are positioned almost perpendicular with respect to the N1–N2–N3–Co1 coordination plane with dihedral angles of 81.61° and 77.03° for Co1 and 88.74° and 82.63° for Co2 [52]. There are no intermolecular contacts of note in either structure.

3.2. Catalytic evaluation for ethylene polymerization

To explore the performance of Co1–Co5 as precatalysts for ethylene polymerization, side-by-side investigations were conducted using MAO (Table 2) and MMAO (Table 3) as activators. All polymerizations were conducted in toluene with the ethylene pressure initially fixed at 10 atm and the run time at 30 min. Reaction parameters including run temperature, molar ratio of aluminum to cobalt, and reaction time were subject to a systematic investigation. The resulting polyethylenes were characterized by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) and gel permeation chromatography (GPC). Furthermore, high-temperature 13C NMR spectroscopy was undertaken on selected polyethylene samples in order to provide insight on their microstructural properties. As a matter of course, gas chromatography was performed on post-reaction mixtures which, in all cases, gave no evidence of any oligomeric fractions.

Ethylene polymerization results using Co1–Co5/MAO at PC 2H4 = 10 atma

| Entry | Pre-cat. | T (°C) | Al:Co | t (min) | Mass of PE (g) | Activityb | Mw c (kg⋅mol−1) | Mw/Mn c | Tm d (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co1 | 40 | 2500 | 30 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 16.5 | 2.1 | 135.4 |

| 2 | Co1 | 50 | 2500 | 30 | 10.01 | 10.01 | 11.8 | 2.2 | 130.1 |

| 3 | Co1 | 60 | 2500 | 30 | 11.05 | 11.05 | 10.2 | 2.2 | 129.7 |

| 4 | Co1 | 70 | 2500 | 30 | 4.30 | 4.30 | 7.6 | 2.2 | 129.1 |

| 5 | Co1 | 80 | 2500 | 30 | 2.74 | 2.74 | 5.3 | 2.2 | 127.9 |

| 6 | Co1 | 60 | 1500 | 30 | 8.22 | 8.22 | 11.4 | 2.3 | 130.5 |

| 7 | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 14.74 | 14.74 | 10.4 | 2.2 | 130.4 |

| 8 | Co1 | 60 | 3000 | 30 | 10.51 | 10.51 | 10.3 | 2.2 | 129.8 |

| 9 | Co1 | 60 | 3500 | 30 | 7.50 | 7.50 | 10.7 | 2.2 | 130.1 |

| 10 | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 5 | 5.36 | 32.16 | 9.5 | 2.3 | 129.5 |

| 11 | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 15 | 9.96 | 19.92 | 10.8 | 2.1 | 130.6 |

| 12 | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 45 | 16.96 | 11.31 | 12.8 | 2.2 | 130.1 |

| 13 | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 60 | 18.47 | 9.24 | 13.7 | 2.2 | 130.8 |

| 14e | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 10.21 | 10.21 | 9.9 | 2.3 | 129.5 |

| 15f | Co1 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 6.4 | 2.4 | 127.8 |

| 16 | Co2 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 12.57 | 12.57 | 18.6 | 2.3 | 131.4 |

| 17 | Co3 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 8.55 | 8.55 | 34.2 | 2.1 | 131.6 |

| 18 | Co4 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 14.60 | 14.60 | 13.0 | 2.2 | 130.3 |

| 19 | Co5 | 60 | 2000 | 30 | 9.34 | 9.34 | 20.4 | 2.2 | 131.5 |

aReaction conditions: 2.0 μmol of cobalt precatalyst, 100 mL toluene, 10 atm ethylene; b106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; cmeasured using GPC; dmeasured using DSC; eethylene pressure = 5 atm; fethylene pressure = 1 atm.

Ethylene polymerization results using Co1–Co5/MMAO at PC 2H4 = 10 atma

| Entry | Precat | T (°C) | Al:Co | t (min) | Mass of PE (g) | Activityb | Mw c (kg⋅mol−1) | Mw/Mn c | Tm d (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Co1 | 20 | 2500 | 30 | 3.50 | 3.50 | 38.7 | 2.2 | 132.8 |

| 2 | Co1 | 30 | 2500 | 30 | 3.93 | 3.93 | 27.8 | 2.3 | 132.2 |

| 3 | Co1 | 40 | 2500 | 30 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 17.3 | 2.3 | 130.7 |

| 4 | Co1 | 50 | 2500 | 30 | 1.82 | 1.82 | 14.2 | 2.4 | 130.3 |

| 5 | Co1 | 60 | 2500 | 30 | 1.59 | 1.59 | 13.5 | 2.4 | 130.0 |

| 6 | Co1 | 30 | 2000 | 30 | 3.25 | 3.25 | 29.3 | 2.4 | 131.7 |

| 7 | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 4.55 | 4.55 | 31.5 | 2.3 | 132.0 |

| 8 | Co1 | 30 | 3500 | 30 | 3.58 | 3.58 | 29.7 | 2.4 | 132.2 |

| 9 | Co1 | 30 | 4000 | 30 | 3.24 | 3.24 | 29.0 | 2.2 | 132.0 |

| 10 | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 5 | 2.29 | 13.74 | 29.4 | 2.5 | 132.0 |

| 11 | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 15 | 2.88 | 4.32 | 29.7 | 2.3 | 131.9 |

| 12 | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 45 | 5.39 | 3.59 | 31.9 | 2.2 | 132.3 |

| 13 | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 60 | 5.87 | 2.94 | 33.0 | 2.2 | 132.0 |

| 14e | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 2.91 | 2.91 | 29.6 | 2.3 | 132.4 |

| 15f | Co1 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 29.4 | 2.4 | 131.8 |

| 16 | Co2 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 3.55 | 3.55 | 29.6 | 2.3 | 133.3 |

| 17 | Co3 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 3.32 | 3.32 | 32.0 | 2.3 | 133.9 |

| 18 | Co4 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 4.07 | 4.07 | 30.6 | 2.1 | 132.4 |

| 19 | Co5 | 30 | 3000 | 30 | 3.35 | 3.35 | 30.1 | 2.1 | 133.3 |

aReaction conditions: 2.0 μmol of cobalt precatalyst, 100 mL toluene, 10 atm ethylene; b106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; cmeasured using GPC; dmeasured using DSC; eethylene pressure = 5 atm; fethylene pressure = 1 atm.

3.2.1. Evaluation of Co1–Co5/MAO as ethylene polymerization catalysts

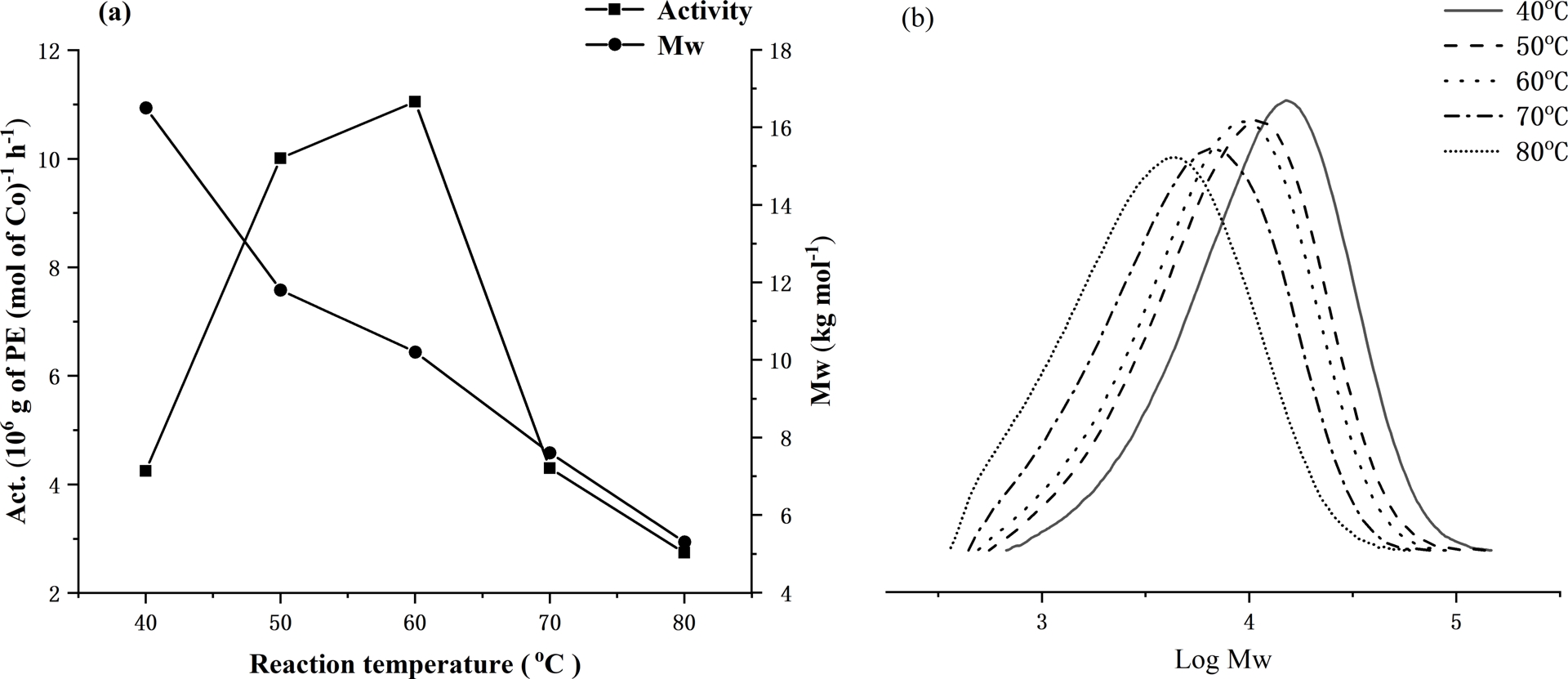

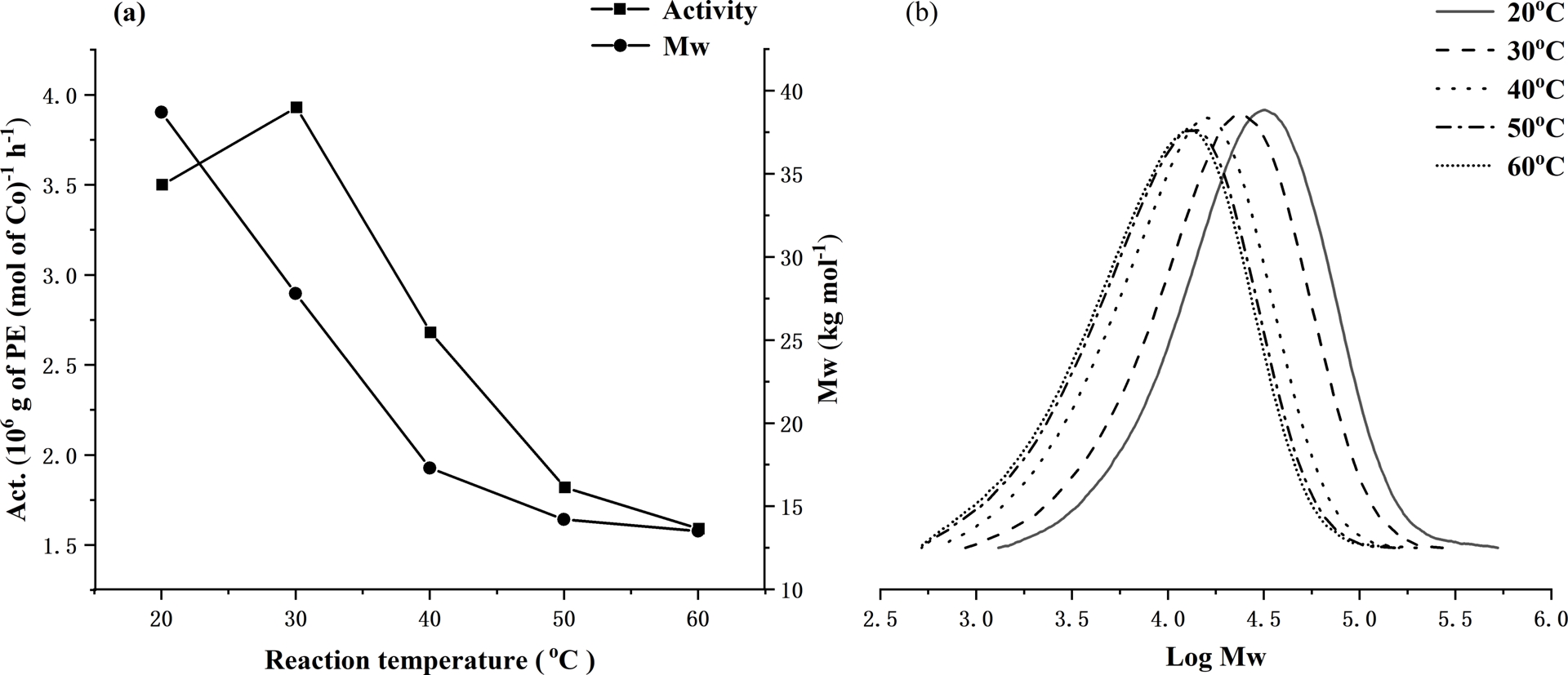

To pinpoint an effective set of reaction conditions to screen all five complexes with MAO, Co1 was firstly employed as the test precatalyst to ascertain the optimal temperature, Al:Co molar ratio, and run time. Firstly, with the Al:Co ratio set at 2500, the reaction temperature was changed from 40 to 80 °C (entries 1–5, Table 2), revealing the peak activity of 11.05 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 to occur at 60 °C (entry 3, Table 2). On further increasing the temperature, the level of activity dropped to 2.74 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 at 80 °C (entries 5, Table 2). This finding can likely be accredited to both decomposition of the active species and the lower concentration of ethylene in toluene at higher temperature [55]. Meanwhile, as the reaction temperature increased, the molecular weight of the resulting polyethylene decreased from 16.5 down to 5.3 kg⋅mol−1, which can be accounted for by a higher rate of chain termination as the temperature was raised. Nevertheless, all polymers generated under these conditions exhibited molecular weights (Mw range: 16.5–5.3 kg mol−1) that can classify them best as polyethylene waxes. The effects of reaction temperature on activity and polymer molecular weight using Co1/MAO are further displayed in Figure 3a, while the corresponding GPC traces are collected in Figure 3b.

For Co1/MAO: (a) dual plots of polymer molecular weight and catalytic activity as a function of run temperature and (b) GPC traces showing variations of log Mw of the polymer as the run temperature is varied (entries 1–5, Table 2).

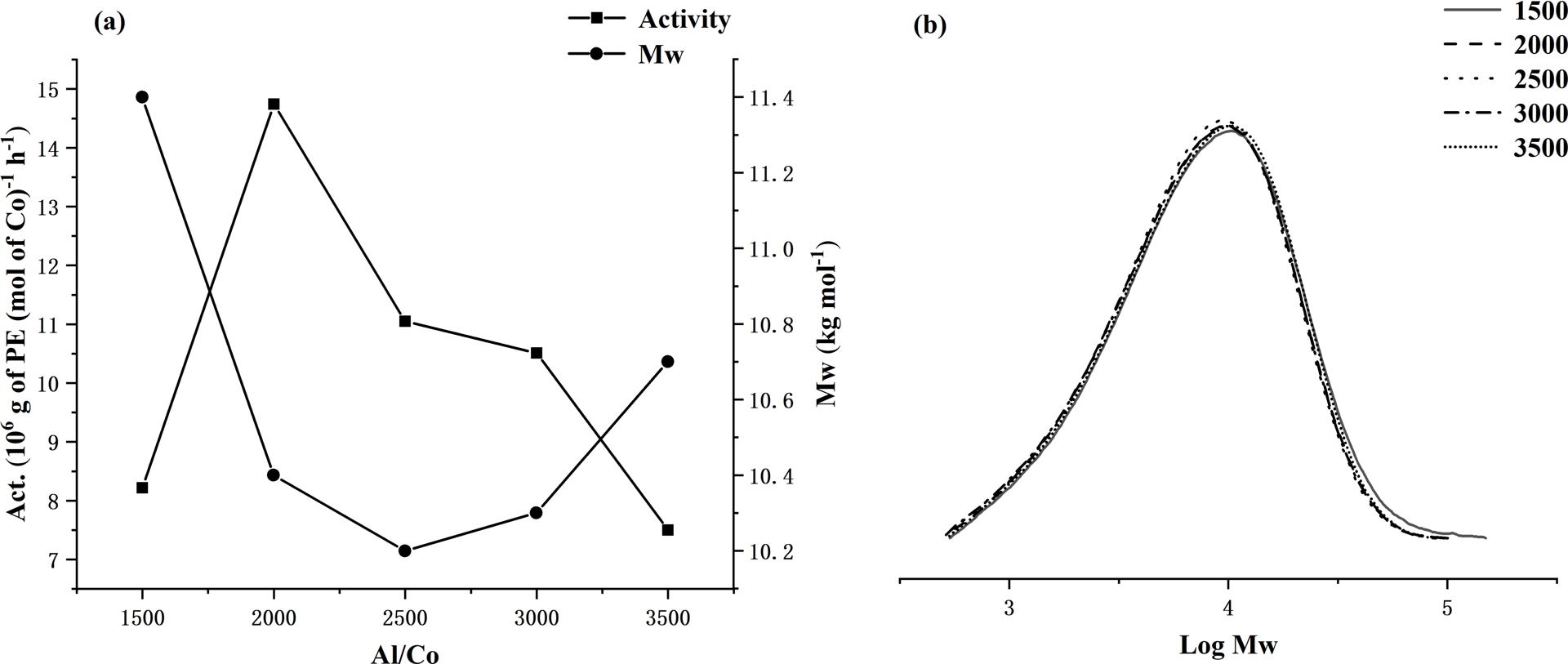

With the run temperature maintained at the optimal 60 °C, the Al:Co molar ratio using Co1/MAO was increased from 1500 to 3500; the results are collected in Table 2 and illustrated in Figure 4. On increasing the ratio, the highest activity of 14.74 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 was achieved with 2000 molar equivalents of MAO (entry 7, Table 2). However, on further raising the Al:Co molar ratio to 3500, the catalytic activity dropped by nearly half to 7.50 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1. In terms of the polymer molecular weight, this remained within a narrow range as the molar ratio was increased, although the slight drop from 11.4 kg⋅mol−1 at 1500 to 10.7 kg⋅mol−1 at 3500 may suggest the onset of some chain transfer from the cobalt to aluminum [56, 57, 58, 59].

For Co1/MAO: (a) dual plots of polymer molecular weight and catalytic activity as a function of Al:Co molar ratio and (b) GPC traces showing the modest effect of Al:Co molar ratio on log Mw (entries 3 and 6–9, Table 2).

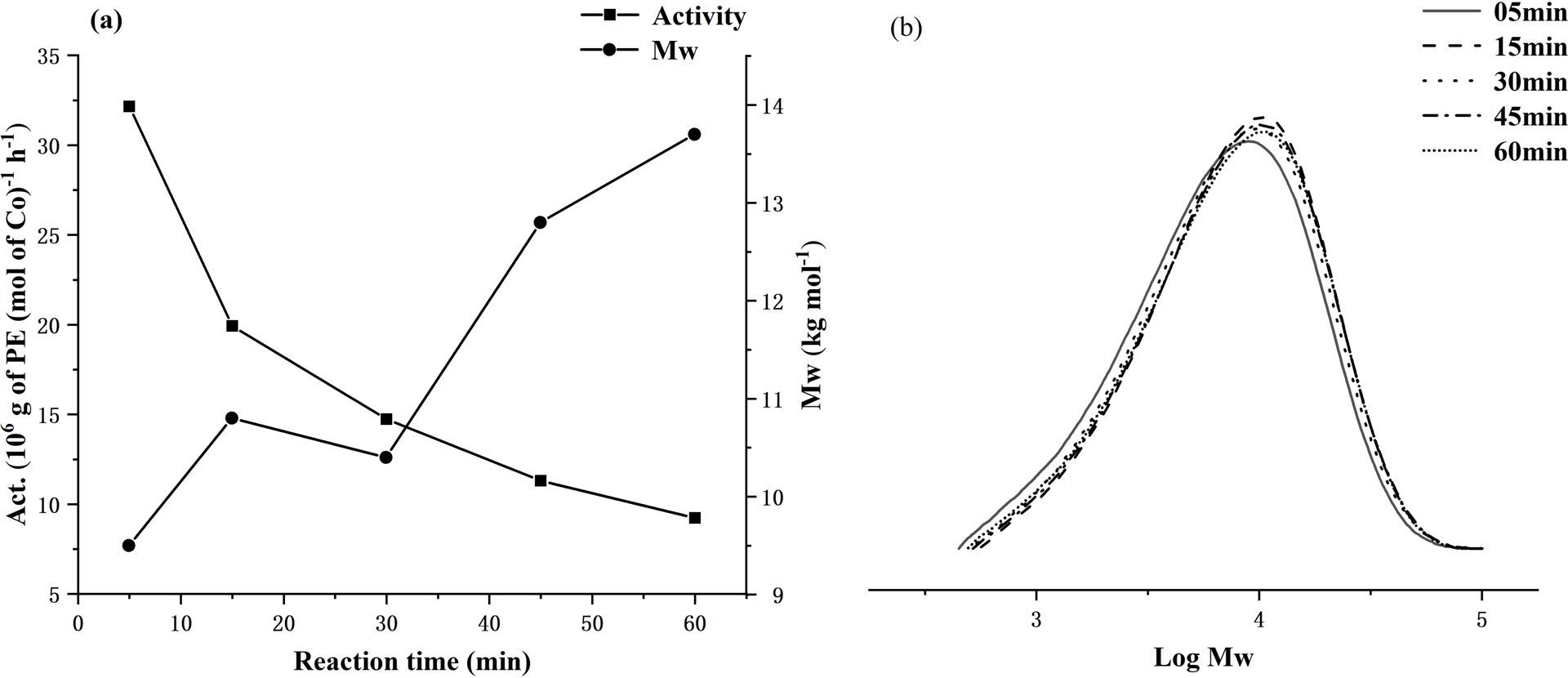

The influence of reaction time on the polymerization behavior of Co1/MAO and the lifetime of the active species was then investigated with the reaction temperature fixed at 60 °C and the Al:Co molar ratio at 2000. Specifically, the tests were run over 5, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min (entries 7 and 10–13, Table 2) and revealed the maximum activity of 32.16 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 to be detected within 5 min (entries 10, Table 2). After this initial spike in activity, the level slowly decreased to only 9.24 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 after 1 h (entry 13, Table 2), which suggests that Co1/MAO displayed good stability and appreciable lifetime. Evidently, the active species was quickly generated upon addition of MAO and then underwent a steady deactivation over time [60, 61]. As for the polymer molecular weight, this was found to slowly increase over reaction time (Figure 5), which demonstrated that the active species remained potent throughout [62, 63].

For Co1/MAO: (a) dual plots of polymer molecular weight and catalytic activity as a function of run time and (b) GPC traces showing the effect of run time on log Mw of the polymer (entries 7 and 10–13, Table 2).

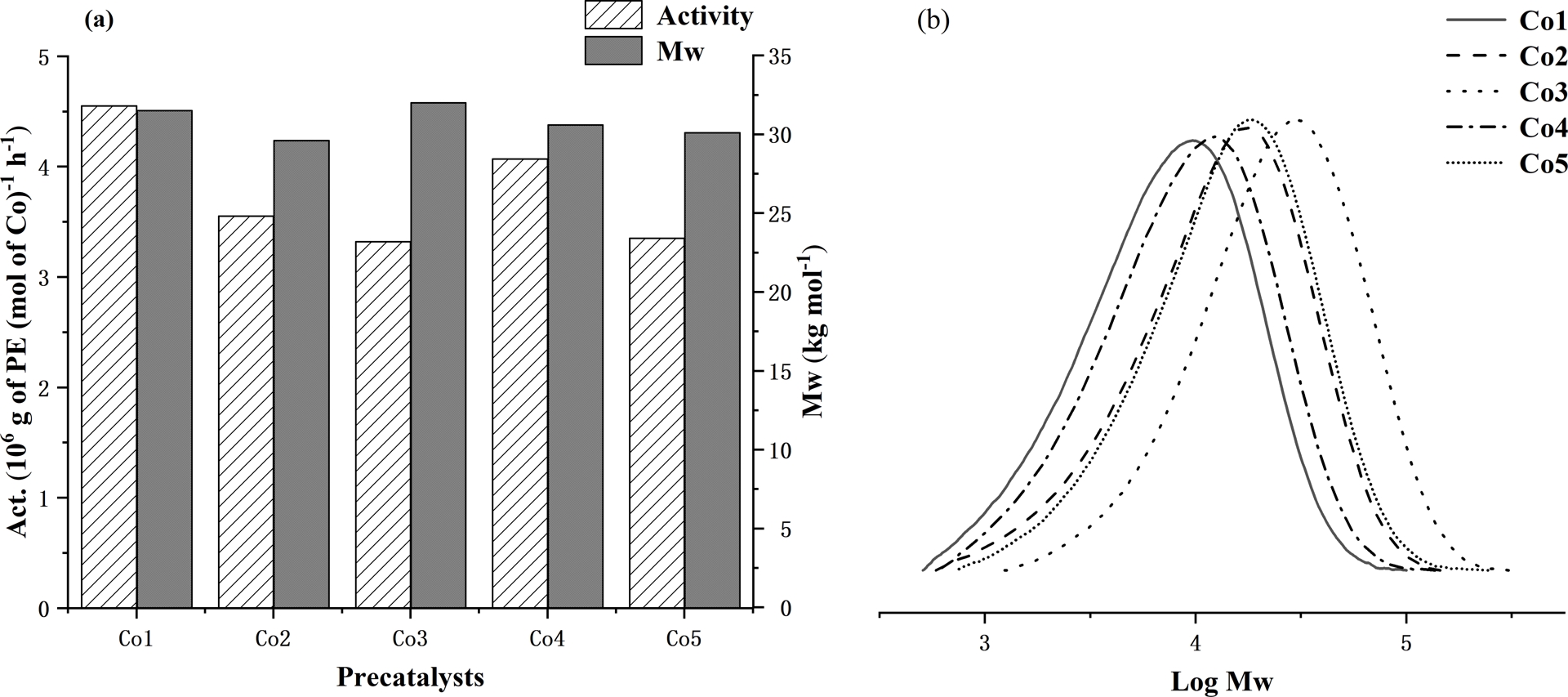

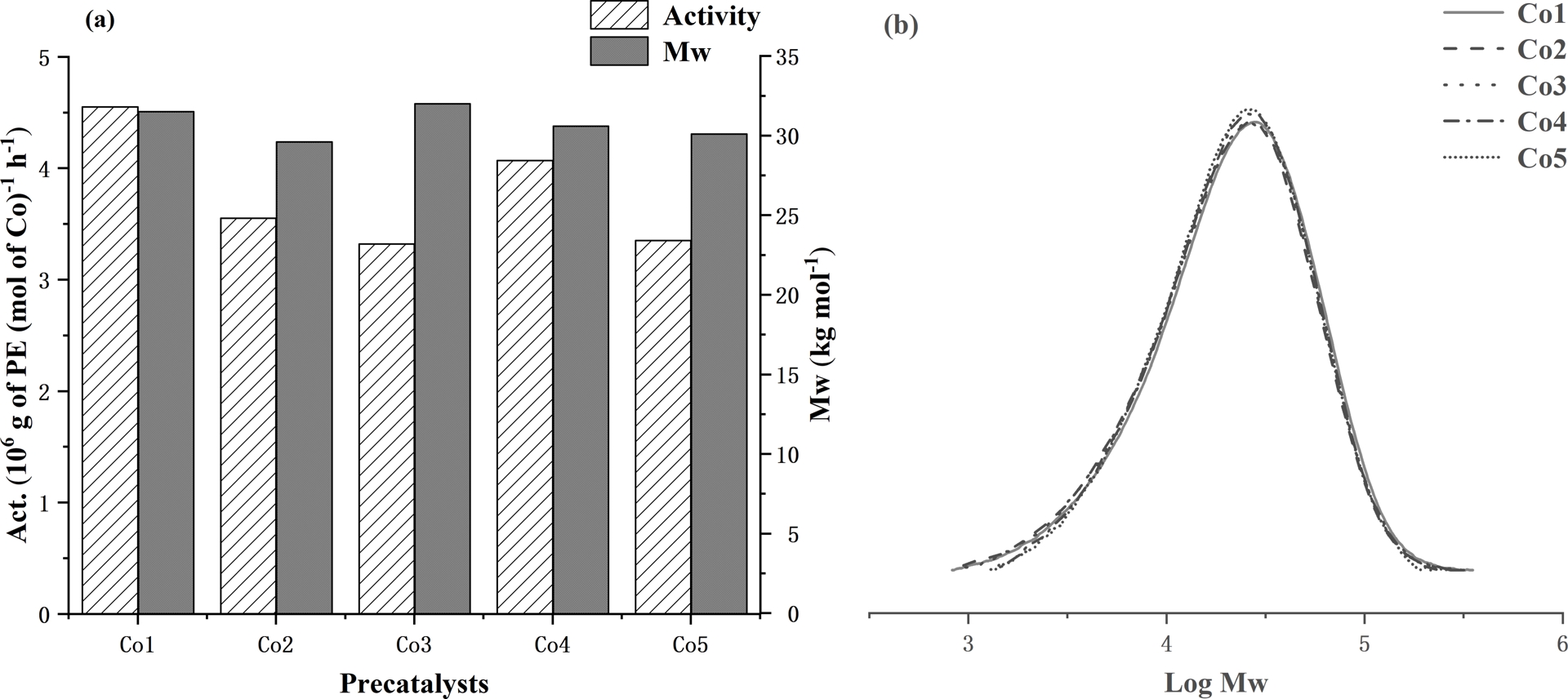

With the optimum polymerization conditions established for Co1/MAO as 60 °C (run temperature), 2000 (Al:Co molar ratio), and 30 min (run time), Co2–Co5 were then investigated similarly (entries 16–19, Table 2). All precatalysts exhibited high activity and thermal stability with the activity falling in the order: Co1 (2,6-di(Me)) > Co4 (2,4,6-tri(Me)) > Co2 (2,6-di(Et)) > Co5 (2,6-di(Et)-4-Me) > Co3 (2,6-di(iPr)). Evidently, the steric properties of the precatalyst affect the performance with more sterically bulky ortho-groups impeding coordination and insertion of ethylene, resulting in lower activity [56]. By contrast, the bulkiest precatalyst Co3 afforded the polymer exhibiting the highest molecular weight (34.2 kg⋅mol−1, entry 17, Table 2) of the series, where the steric properties have the additional role of hindering chain termination pathways leading to polyethylene of relatively high molecular weight [57]. The effects of precatalyst type on activity and polymer molecular weight are further displayed in Figure 6a, while the corresponding GPC traces are collected in Figure 6b.

(a) Bar chart displaying catalytic activity and polymer molecular weight with respect to the cobalt precatalyst and (b) GPC traces showing log Mw as a function of the precatalyst (entries 7 and 16–19, Table 2); all runs conducted with MAO as activator at PC 2H4 = 10 atm.

3.2.2. Evaluation of Co1–Co5/MMAO as ethylene polymerization catalysts

With MMAO now employed as the activator, Co1 was again employed to optimize the conditions of the polymerization. As with MAO, this initial study focused on the effects of run temperature, Al:Co molar ratio, and reaction time; the complete set of results are gathered in Table 3. With the Al:Co molar ratio firstly set at 2500, the polymerization temperature was increased from 20 to 60 °C (entries 1–5, Table 3). In this case, the highest activity of 3.93 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 was observed at 30 °C rather than 60 °C as with MAO, highlighting the importance of the activator on the active catalyst’s temperature stability. With regard to the polyethylene, molecular weights gradually lowered as the reaction temperature was increased (Figure 7), which can be accounted for by the faster chain termination at higher temperature [52]. In comparison with the results obtained using MAO, the polyethylenes produced using Co1/MMAO generally showed slightly higher molecular weights but possessed similarly narrow dispersities (Mw/Mn⩽2.4). Additionally, Co1/MMAO showed in general lower catalytic activities, which could plausibly derive from the differences between MMAO and MAO, and their effects on the active species.

For Co1/MMAO: (a) dual plots of polymer molecular weight and catalytic activity as a function of run temperature and (b) GPC traces showing the effect of run temperature on the log Mw of the polymer (entries 1–5, Table 3).

Next, the Al:Co molar ratio using Co1/MMAO was altered with the run temperature maintained at 30 °C (entries 2 and 6–9, Table 3) leading to the highest activity of 4.55 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 being achieved with a ratio of 3000 (entry 7, Table 3). As with Co1/MAO, the catalytic activity gradually declined at higher ratios, while polymer molecular weight remained relatively constant (Mw range: 27.8–31.5 kg mol−1) but with a perceptible decrease especially at higher ratios.

On modifying the reaction time from 5 to 60 min (entries 7 and 10–13, Table 3), the activity of Co1/MMAO reached a maximum of 13.74 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 after 5 min and then revealed a gradual decrease to 2.94 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 after 60 min, a finding suggesting that the active species was formed quickly but then underwent deactivation as time elapsed [58]. The effect of ethylene pressure was also explored, with the activity of Co1/MMAO found to fall as the pressure was lowered from 10 atm (4.55 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; entry 7) to 5 atm (2.91 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; entry 14) to 1 atm (1.05 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; entry 15); similar effects were seen with MAO and reflect the importance of ethylene pressure to chain propagation in these systems.

With the optimal conditions for Co1/MMAO now in place (run temperature = 30 °C, Al:Co molar ratio = 3000), the remaining precatalysts Co2–Co5 were evaluated accordingly. In terms of catalytic activity, the trend essentially mimics that seen with MAO: Co1 (2,6-di(Me)) > Co4 (2,4,6-tri(Me)) > Co2 (2,6-di(Et)) > Co5 (2,6-di(Et)-4-Me) ∼ Co3 (2,6-di(iPr)). Again, the ortho-methyl precatalysts Co1 and Co4 exhibit higher catalytic activity than their bulkier ortho-ethyl or ortho-isopropyl counterparts (Co2, Co3, Co5); this observation is consistent with that observed with MAO. In all cases, the dispersity of the polyethylene is narrow (Mw/Mn range: 2.4–2.1), which is also borne out in the GPC traces (Figure 8), which supports the single-site-like nature of the active species.

(a) Bar chart displaying catalytic activity and molecular weight of the polymer with respect to the cobalt precatalyst and (b) GPC traces showing log Mw as a function of the precatalyst (entries 7 and 16–20, Table 3); all runs performed using MMAO as activator and PC 2H4 = 10 atm.

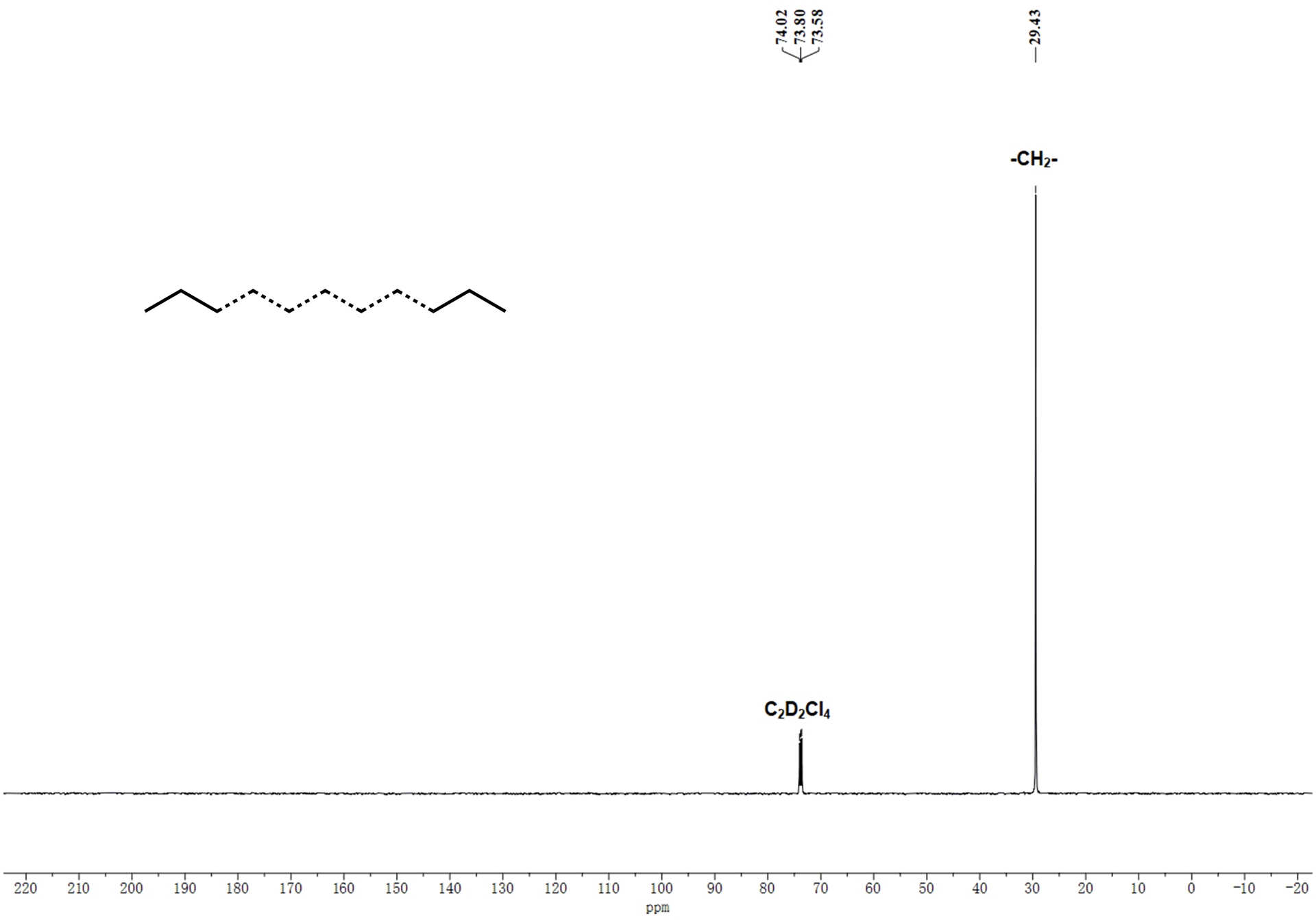

3.3. Microstructural analysis of the polyethylenes

As can be gathered from Tables 2 and 3, all polyethylenes display melting temperatures (Tm) in excess of 127 °C, values that are typical of linear high-density polyethylene. To corroborate this assertion, two representative samples obtained using Co1/MAO at 60 °C (entry 7, Table 2; Mw = 10.4 kg⋅mol−1) and Co1/MMAO at 30 °C (entry 7, Table 3; Mw = 31.5 kg⋅mol−1) were subjected to high-temperature 13C NMR spectroscopy (recorded at 100 °C in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d2, see Figure 9 and Figure S3). For the sample obtained using Co1/MAO at 60 °C, a characteristic singlet resonance at 𝛿 30.00 corresponds to the methylene repeat unit (–CH2–) for a linear polyethylene [52]; the absence of additional peaks corresponding to chain ends is presumably attributable to the relatively high molecular weight of the sample.

13C NMR spectrum of the PE sample produced using Co1/MAO as catalyst at 60 °C (entry 7, Table 2); recorded at 100 °C in 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane-d2.

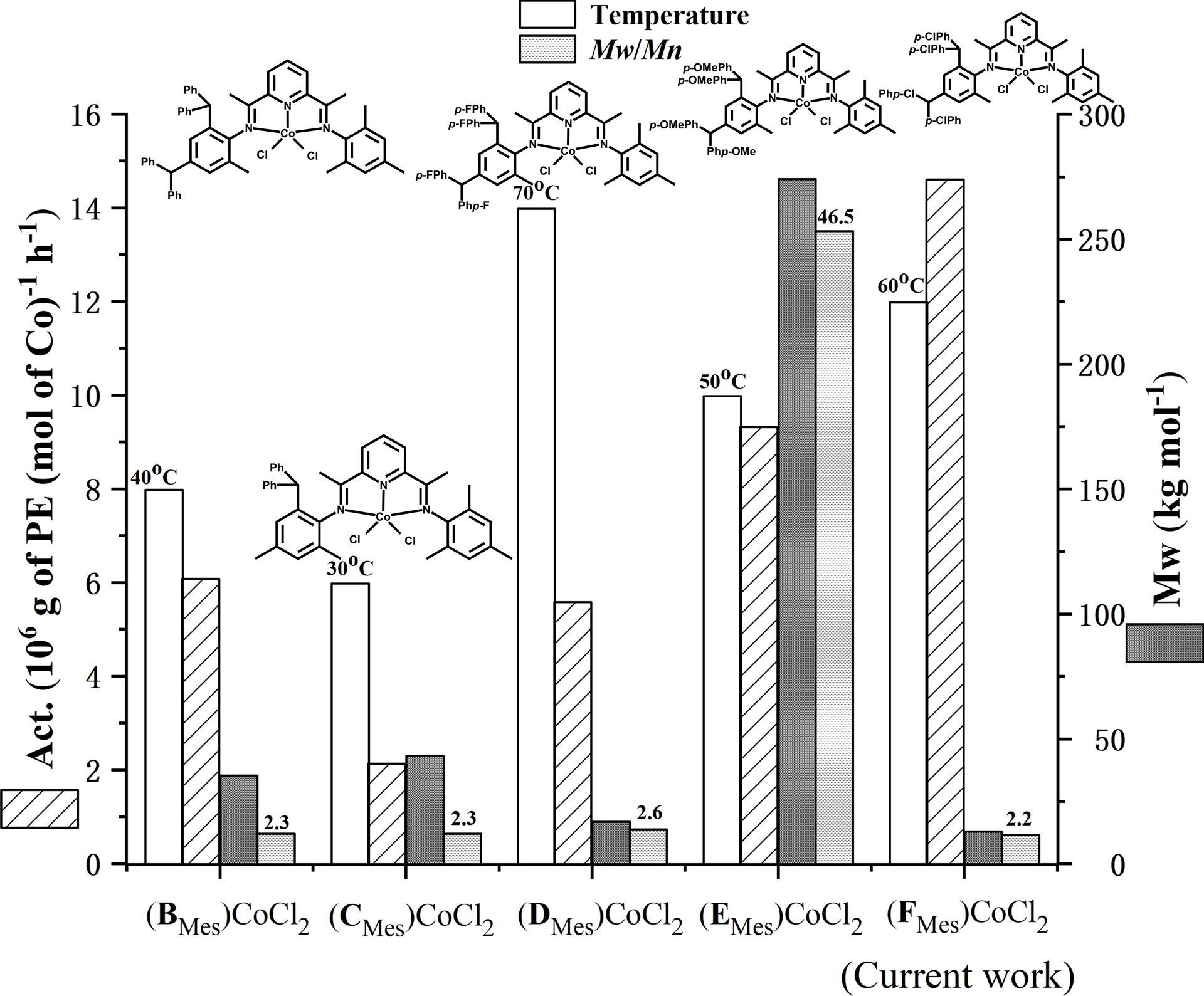

3.4. Comparison of the current cobalt catalysts with previously reported examples

To help contextualize the findings in this work, we have extracted key performance data for mesityl-containing Co4/MAO [(FMes)CoCl2] obtained herein (entry 18, Table 2) and assembled this alongside those previously reported for (BMes)CoCl2, (CMes)CoCl2, (DMes)CoCl2, and (EMes)CoCl2 (Figure 10); all tests were obtained under optimized conditions at PC 2H4 = 10 atm using MAO [47, 48, 49, 50]. All five systems are structurally related with (BMes)CoCl2, (DMes)CoCl2, (EMes)CoCl2, and (FMes)CoCl2 all incorporating N-2-Me-4,6-bis(4,4′-X2dibenzhydryl)phenyl (X = H, F, OMe, Cl) substitution while (CMes)CoCl2, N-2,4-diMe-6-dibenzhydrylphenyl substitution. For the most closely related systems (BMes)CoCl2, (DMes)CoCl2, (EMes)CoCl2, and (FMes)CoCl2, it is evident that chloro-containing (FMes)CoCl2 is the most active (14.6 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1; entry 18, Table 2) but forms the lowest molecular weight polymer (Mw = 13.0 kg⋅mol−1; entry 18, Table 2). Conversely, (EMes)CoCl2 bearing an electron donating methoxy-substituent showed moderate activity, but the resulting polyethylene afforded the highest molecular weight (Mw = 274.0 kg⋅mol−1) and broad dispersity [50]. Evidently, these results underline the electronic influence played by the para-groups in the benzhydryl group on catalytic performance. By comparison, (CMes)CoCl2 showed the lowest activity (2.1 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1) [48], which could be the result of a combination of both steric and electronic effects. Nevertheless, all these classes of benzhydryl-substituted bis(arylimino)pyridyl–cobalt catalyst impart excellent control as evidenced by the single-site-like behavior (Mw/Mn range: 2.2–2.6).

Comparison of thermal stability, catalytic activity, polyethylene molecular weight, and dispersity for (BMes)CoCl2, (CMes)CoCl2, (DMes)CoCl2, and (EMes)CoCl2 (Chart 1) with the current precatalyst (FMes)CoCl2 (Co4); all polymerization runs were performed at PC 2H4 = 10 atm under their optimal conditions.

4. Conclusions

In summary, five examples of unsymmetrical 2,6-bis(arylimino)pyridine-cobalt complexes (Co1–Co5), incorporating one N-2,4-bis(di(4-chlorophenyl)methyl)-6-methylphenyl group and one variable N-aryl group, have been successfully synthesized from their corresponding free N′,N,N′′-ligands. All complexes were formed in high yield and fully characterized including by single crystal XRD for Co1 and Co2. Under activation with MAO and MMAO, Co1–Co5 all demonstrated their ability to promote ethylene polymerization with high activities reaching up to 14.74 × 106 (g of PE)⋅(mol of Co)−1⋅h−1 for Co1/MAO. Moreover, they could deliver this at an appreciable operating temperature of 60 °C, which is notably higher than that seen in previously reported related examples. Furthermore, the polymerizations are well controlled as is evidenced by narrow molecular-weight distributions. Comparison with a series of structurally related benzhydryl-containing cobalt catalysts highlights the important role of the para-chloride group. Overall, this is a rare example of a cobalt-based catalyst system that possesses the combined properties of high thermal stability and high activity producing highly linear polyethylene. This also represents an excellent demonstration of the capacity of rational ligand design to improve the performance of ethylene polymerization catalysts.

Declaration of interests

The authors do not work for, advise, own shares in, or receive funds from any organization that could benefit from this article, and have declared no affiliations other than their research organizations.

Funding

GAS is grateful to the Chinese Academy of Sciences for a President’s International Fellowship for Visiting Scientists (grant no. 2025PVB0034).

Underlying Data

The data underlying the article can be obtained from the corresponding author.

CCDC-2464596 for Co1 and 2464597 for Co2 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this article; these data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html.

CC-BY 4.0

CC-BY 4.0