Version abrégée

1 Introduction

Durant les vingt dernières années, les études tectoniques ont mis en évidence la structure de « chevauchement et plissement » de l'Apennin septentrional, en attirant l'attention sur les structures liées à la compression et à la tectonique extensive ultérieure ([9] avec bibliographie), sans aborder toutefois certains problèmes structuraux qui peuvent avoir d'importantes retombées sur l'évolution de la chaı̂ne. Un de ces problèmes concerne l'évolution tectono-métamorphique de la Nappe toscane (TN) et du Complexe métamorphique apuan (AAMC), évolutions considérées comme identiques par de nombreux auteurs [9,14] : en effet, ces deux unités ont été déformées successivement à divers niveaux structuraux, avec une phase D1 compressive, suivie par une phase D2 extensive. En fait, l'analyse structurale comparée des deux unités dans le secteur sud-occidental des Alpes apuanes (Fig. 1) a mis en évidence une histoire tectono-métamorphique indépendante de l'une par rapport à l'autre.

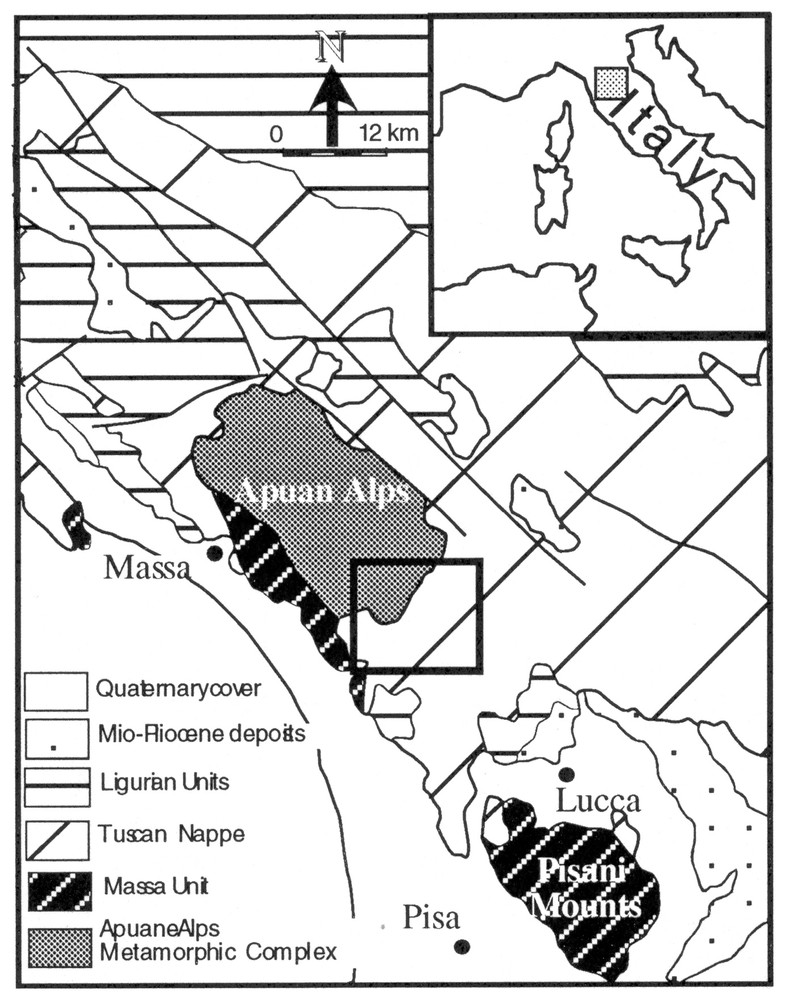

Geological sketch map of the Northern Apennines and location of the study area.

Carte géologique simplifiée de l'Apennin septentrional et localisation de la zone étudiée.

2 Cadre géologique

La chaı̂ne orogénique de l'Apennin résulte de la collision entre la microplaque corso-sarde et le promontoire Adria à partir de l'Oligocène tardif [3,6]. La chaı̂ne a été constituée par le charriage de diverses unités tectoniques, déposées, soit sur croûte océanique (Unités ligures), soit sur croûte continentale (Unités toscanes). Les Unités toscanes, de bas en haut, sont représentées par le complexe métamorphique apuan (AAMC), caractérisé par des roches déformées sous faciès schistes verts, et dont l'âge est compris entre le Paléozoı̈que et l'Oligocène, par l'unité de Massa, constituée par des roches d'âge compris entre le Paléozoı̈que et le Trias supérieur et caractérisées par un métamorphisme avec des pressions plus élevées que celles de l'unité sous-jacente [16] ; la Nappe toscane (TN), caractérisée par des roches avec un très faible métamorphisme et un âge compris entre le Trias supérieur et l'Oligocène. Durant l'Oligocène supérieur et le Miocène inférieur, les nappes ont été transportées vers le nord-est, avec développement de chevauchements, plis et failles inverses [8]. Les datations radiométriques dans le Complexe métamorphique apuan ont fourni un âge de 27 Ma pour la première déformation D1 [17] et un âge de 8 Ma pour la fin de la deuxième phase de déformation D2 [17], pendant laquelle ce Complexe a été exhumé [9]. Les études sur les traces de fission des apatites indiquent, pour les derniers stades de soulèvement, des âges compris entre 8 et 5 Ma pour la TN et entre 6 et 2 Ma pour l'AAMC [2].

Dans la région étudiée affleure, soit la TN, soit l'AAMC, même si les deux unités ne sont pas représentées par tous leurs termes. L'AAMC, fortement tectonisé, affleure en écailles tectoniques, interprétées par Carmignani et al. [11] comme portions de plis F1 kilométriques développés durant la phase de chevauchement des unités et déformés durant la phase tectonique extensive ultérieure. Deux phases de déformations ont été reconnues également dans la TN ; elles ont été liées aux phases reconnues dans l'AAMC [10].

3 Analyse structurale

L'analyse structurale a mis en évidence la présence de quatre phases de déformation dans l'AAMC (D1–D2–D3–D4AAMC) et de trois dans la TN (D1–D2–D3TN) (Tableau 1).

Synoptic table of the deformation phases with their main structural features in the Tuscan Nappe and Apuan Alps Metamorphic Complex. Data from Franceschelli et al. [15].

Tableau synoptique des phases déformatives avec les principales caractéristiques structurales de la Nappe toscane et du Complexe métamorphique apuan. Données de Franceschelli et al. [15].

3.1 Le Complexe métamorphique apuan

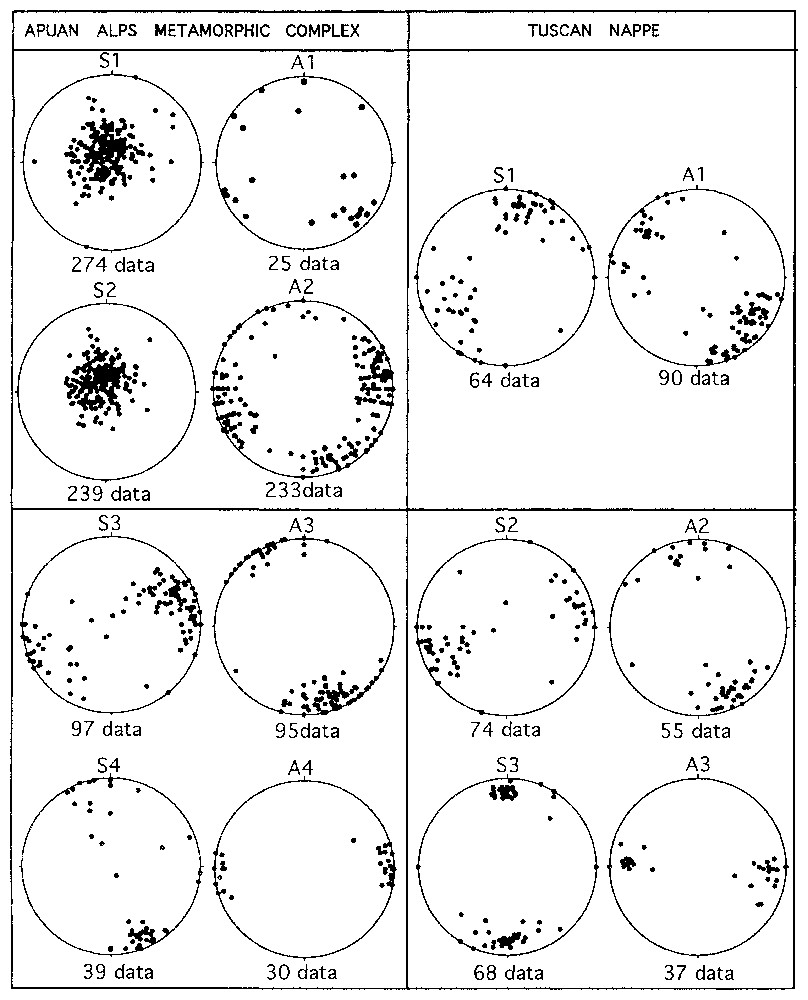

La première phase de déformation (D1AAMC) est associée au développement d'une foliation pénétrative S1, dans une ambiance de schistes verts [15]. Les plis F1 appartiennent aux classes I C et II de Ramsay [19]. Les linéations extensives L1, avec des orientations moyennes NW–SE, sont mises en évidence par des cristaux de quartz et de calcite, et par les fibres de quartz dans les ombres de pression autour de cristaux de pyrite. La phase D2AAMC est associée au développement de plis F2, généralement asymétriques, avec des charnières épaisses, des flancs étirés et des plans axiaux inclinés ; parallèlement se développe une foliation S2. Les axes A2, très dispersés, montrent des orientations variables, entre SSE–NNW, avec de faibles inclinaisons vers le SSE, et ENE–WSW, avec des inclinaisons vers l'ENE (Fig. 3). Associées à D2, se trouvent aussi des zones de cisaillements fragiles–ductiles, avec des directions de transport tectonique vers le nord-est. La troisième phase (D3AAMC) est associée au développement de plis parallèles et droits (classe I B, [19]), avec des ouvertures angulaires comprises entre 70 et 170° et des axes orientés NNW–SSE, faiblement inclinés vers le SSE (Fig. 3). Une foliation S3 se développe parallèlement aux plans axiaux, avec les caractéristiques d'un clivage de crénulation zoné. La dernière phase de déformation reconnue (D4AAMC) est associée, elle aussi, à des plis verticaux et parallèles, avec des directions axiales sensiblement est–ouest (Fig. 3) et des angles d'ouverture variables, compris entre 120 et 170°.

Stereographic projections of the main structural elements of the studied tectonic units (Schmidt equal projection, lower hemisphere).

Diagrammes stéréographiques des éléments structuraux relatifs aux deux unités tectoniques étudiées (projection équivalente de Schmidt, hémisphère inférieur).

3.2 La Nappe toscane

La première phase de déformation (D1TN) est caractérisée par de rares plis asymétriques, déversés vers le nord-est avec des plans axiaux plongeant faiblement vers le sud-ouest et appartenant à la classe I C [19]. La foliation S1, développée en condition métamorphique de très bas degré, affecte des caractéristiques très différentes en fonction des divers lithotypes intéressés, allant d'une foliation pénétrative (slaty cleavage) à un clivage disjonctif espacé. À la phase D1 sont associées des zones de cisaillements fragiles–ductiles, avec un sens de mouvement vers le nord-est. Les axes A1 et les linéations d'intersection ont des orientations variant entre N120° et N160° et plongent d'environ 30° vers le sud-est (Fig. 3). La phase D2TN est responsable de plis F2 de dimensions kilométriques et renversés vers l'ouest. Les plis F2 (appartenant aux classes 1B et 1C) présentent des plans axiaux fortement inclinés vers l'est, parallèlement auxquels se développe une foliation de crénulation espacée S2. La phase D3TN produit des plis F3 ouverts (classe 1B), avec des plans axiaux très inclinés. La foliation S3 a la caractéristique d'un clivage de crénulation espacé. Les axes A3 ont des orientations est–ouest et plongent faiblement vers l'est (Fig. 3). Les dernières structures reconnues sont des plis avec des plans axiaux horizontaux et des failles directes ayant des inclinaisons plus ou moins fortes [10].

4 Discussion et conclusion

L'analyse structurale a mis en évidence, dans la région étudiée, la présence d'une tectonique polyphasée plus complexe que celle reconnue jusqu'à présent, tant dans la TN que dans l'AAMC (Tableau 1). En particulier, dans l'AAMC, après les deux phases de déformation pénétratives (D1 et D2AAMC), ont été reconnues deux phases tardives (D3 et D4AAMC), associées encore à un régime tectonique compressif, avec développement de plis verticaux. À l'inverse, dans la TN a été reconnue une seule phase pénétrative (D1TN), suivie par deux systèmes de plis tardifs (D2 et D3TN). Les deux unités ne peuvent pas avoir partagé entièrement la même histoire de déformation. En outre, le contact tectonique entre les deux unités (Fig. 2), a été déformé par les deux dernières phases plicatives reconnues dans les deux unités (D3 et D4AAMC, D2 et D3TN) : le charriage de la TN sur l'AAMC doit donc avoir eu lieu avant les deux phases tardives.

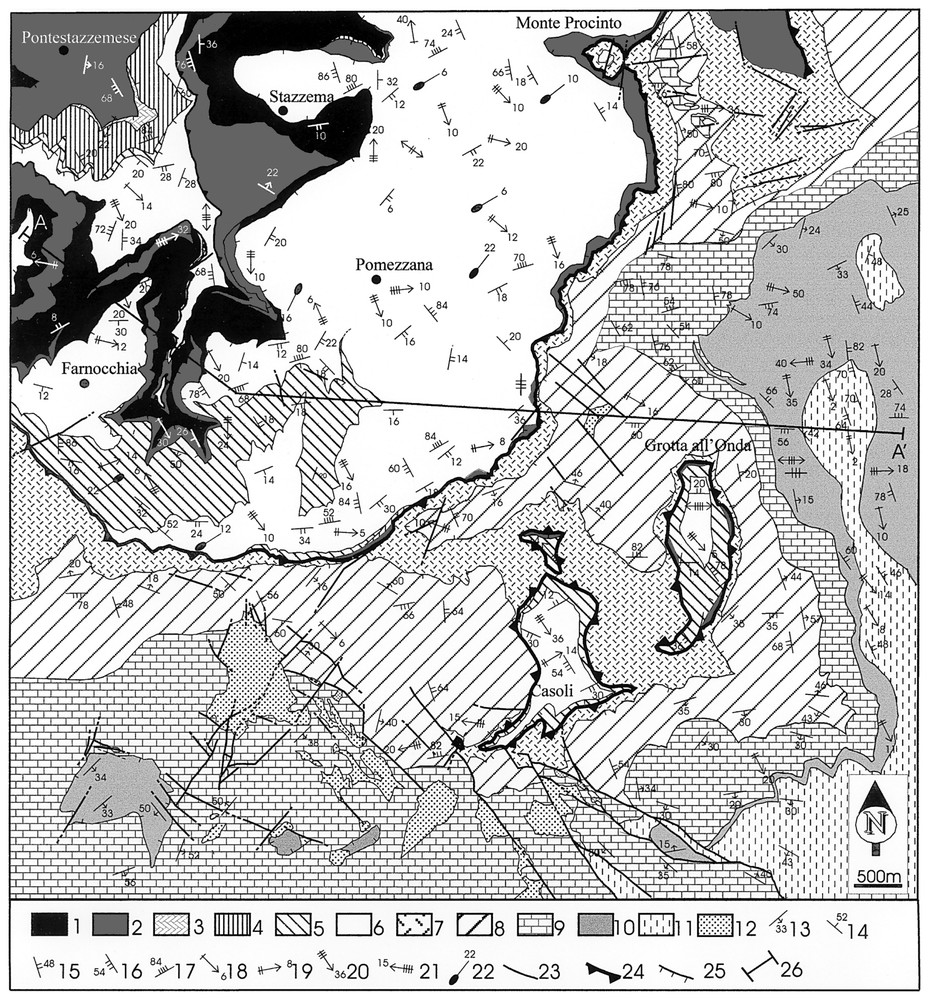

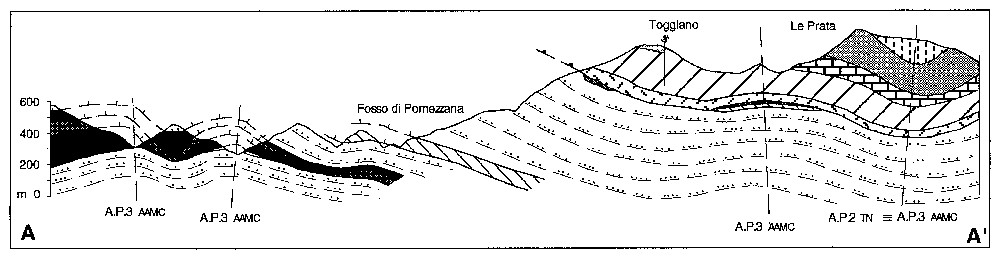

A. Geological schematic map of the study area. 1) ‘Filladi inferiori’ and ‘Porfiroidi e Scisti porfirici’; 2) Grezzoni; 3) Brecce di Seravezza; 4) ‘Marmi’ and ‘Calcare selcifero’; 5) ‘Scisti sericitici’ and ‘Cipollini’; 6) ‘Pseudomacigno’; 7) ‘Calcare cavernoso Auctt.’; 8) ‘Calcari & Marne a Rhaetavicula contorta’; 9) ‘Calcare massiccio’, ‘Calcare ad Angulati’, ‘Calcare Rosso Ammonitico’; 10) ‘Calcare selcifero’; 11) ‘Marne a Posidonia’, ‘Calcare selcifero superiore’, ‘Maiolica’; 12) ‘Brecce di Metato’; 13) bedding surfaces; 14) S1 foliation; 15) S2 foliation; 16) S3 foliation; 17) S4 foliation; 18) A1 axes; 19) A2 axes; 20) A3 axes; 21) A4 axes; 22) stretching lineations; 23) faults; 24) primary tectonic boundaries; 25) secondary tectonic boundaries; 26) trace of geological cross section A–A′ of Fig. 2b. B. Geological cross-section A–A′.

A. Carte géologique schématique de la région étudiée. 1) Filladi inferiori et Porfiroidi e Scisti porfirici ; 2) Grezzoni ; 3) brèches de Serravezza ; 4) Marmi et Calcare selcifero ; 5) Scisti sericitici et Cipollini ; 6) Pseudomacigno ; 7) Calcare Cavernoso Auct. ; 8) Calcari e Marne a Rhaetavicula contorta ; 9) Calcare Massiccio, Calcari ad Angulati, Calcare Rosso Ammonitico ; 10) Calcare selcifero ; 11) Marne a Posidonia, Calcare selcifero superiore, Maiolica ; 12) Brecce di Metato ; 13) surface de stratification ; 14) foliation de première phase ; 15) foliation de deuxième phase ; 16) foliation de troisième phase ; 17) foliation de quatrième phase ; 18) axes de première phase ; 19) axes de deuxième phase ; 20) axes de troisième phase ; 21) axes de quatrième phase ; 22) linéations d'extension maximale ; 23) failles ; 24) contacts tectoniques primaires ; 25) contacts tectoniques secondaires ; 26) localisation de la coupe géologique A–A′ de la Fig. 2b. B. Coupe géologique A–A′.

Pendant les déformations antérieures (D1 et D2AAMC et D1TN), les deux unités ont pu avoir eu une évolution tectonique et métamorphique indépendante (Tableau 1). Le caractère tardif de la superposition de la TN sur l'AAMC s'accorde bien avec les degrés métamorphiques différents enregistrés par les deux unités [15,16]. L'interprétation de certains auteurs, selon lesquels la charge lithostatique de la TN est suffisante pour expliquer le métamorphisme de l'AAMC [15], doit être remise en question, non seulement du fait du caractère différent des déformations reconnues dans les deux unités, mais aussi à cause de l'interposition, sur le versant nord-occidental du Massif apuan de l'Unité de Massa (MU) (Fig. 1), qui présente un degré métamorphique plus élevé que celui de l'AAMC sous-jacente [16]. Le glissement ultérieur de la TN durant les phases tardives de son évolution est en accord avec l'hypothèse selon laquelle une grande partie de l'exhumation de l'AAMC et de la MU pouvait s'être déjà produite. Dans la région étudiée, des cataclasites associées à des surfaces de cisaillement de bas angle ont été reconnues le long des contacts tectoniques de la Nappe toscane sur le Complexe métamorphique apuan (Fig. 2).

La présence, dans la cataclasite, de galets provenant de l'AAMC situé au-dessous et intéressés par deux événements de déformation pénétratifs indique que la cataclasite s'est développée après la phase D2AAMC. Carmignani et Kligfield [9] expliquent la présence des galets polydéformés à l'intérieur des brèches associées au Calcare Cavernoso Auct., en interprétant ce contact comme un chevauchement réactivé pendant la phase tectonique extensive. Bien que cette hypothèse ne puisse pas être exclue, il est nécessaire de souligner que, dans la région étudiée, le transport tectonique associé à la cataclasite est dirigé vers le nord-est, c'est-à-dire qu'il est opposé à celui (vers le sud-ouest) prévu par leur modèle. L'étude au niveau régional du contact et des cataclasites associées, signalées dans les autres zones de Toscane, pourrait aider à une meilleure compréhension de l'évolution de la chaı̂ne tout entière.

1 Introduction

The geometry, the kinematics and the polyphase tectonic evolution of the Northern Apennines are nowadays well constrained [6,9]. By the way, some structural problems, that cover a crucial role in the tectonic evolution of the belt, remain still debated. One of the main problems concerns the polyphase tectonic evolution of the Tuscan Nappe (TN) compared with the one of the Apuan Alps Metamorphic Complex (AAMC). According to many authors [9,10,14], the two units (AAMC and TN) shared the same tectonic evolution, characterised by a D1 compressive deformation and a D2 extensional phase. On the other hand, Boccaletti and Gosso [5] and Boccaletti et al. [7] pointed out to the presence of two penetrative ductile deformations, followed by a minor folding event. Recently, Molli and Meccheri [18] suggested a more complex evolution in the AAMC, pointing out the presence of a progressive deformation for both the D1 and the D2 tectonic phases.

In order to give a contribution to the general discussion on the tectonic evolution of the Northern Apennines, we present the compared structural analysis of a sector of the belt, located in the southern Apuan Alps (Fig. 1) where both the TN and the underlying AAMC come into contact (Fig. 2). This area is very suitable to investigate the relations between the two tectonic units as it offers good expositions and in addition it is not too much affected by late extensional tectonics. The new presented data highlight, at least in the investigated area, a much more complex tectonic evolution than that known till now. We point out that the TN and the AAMC experienced the first part of their tectonometamorphic evolution independently. Further investigations in large areas of the belt could provide constraints for the general tectonic evolution of the Northern Apennines.

2 Geological setting

The Northern Apennines orogenic belt originated during the continental collision, from Late Oligocene, between Corsica–Sardinia microplate and Adria promontory [3,6]. It is made by different tectonic units derived both by oceanic (Liguride sequences) and continental (Tuscan sequences) domains. The Tuscan sequences crop out in different tectonically stacked units: (1) the Apuan Alps Metamorphic Complex (AAMC) is the lower unit and consists of Palaeozoic to Oligocene metamorphic rocks, deformed under greenschist facies metamorphism [15]; (2) the Massa Unit (MU) is constituted by Palaeozoic to Triassic rocks, deformed under higher metamorphic conditions respect to the underlying AAMC [16]; (3) the upper unit is the Tuscan Nappe (TN) and it is composed by Late Triassic to Late Oligocene very low-grade and non-metamorphic sedimentary rocks [4,12].

During Late Oligocene–Early Miocene times, the nappes were displaced eastwards [1], with the development of hinterland-to-foreland propagating thrusts, overturned folds and reverse faults [8]. The Ligurian Units and the TN were stacked onto the external MU and AAMC. Radiometric data from the AAMC pointed out an age of 27 Ma for the D1 phase [17], while a radiometric age of 8 Ma [17] marks the end of the D2 extensional deformation phase [9]. The last stages of uplift have been constrained by apatite fission tracks analyses, indicating ages between 8–5 Ma for the TN, and 6–2 Ma for the AAMC [2].

In the study area, located in the southeastern termination of the Apuan Alps (Fig. 1), both the TN and the underlying AAMC crop out. The two tectonic units are not represented entirely by all their formations (Fig. 2): the TN is represented by its basal Triassic formations (‘Calcare cavernoso’ Auctt. and ‘Calcari & Marne a Rhaetavicula contorta’) followed by Liassic platform deposits (‘Calcare massiccio’) and pelagic limestones and marls (‘Calcare ad Angulati’, ‘Calcare Rosso Ammonitico’, ‘Calcare selcifero inferiore’, ‘Marne a Posidonia’, ‘Calcare selcifero superiore’). The upper part of the sequence is characterised by the discontinuous presence of Cretaceous calcilutites (‘Maiolica’). The younger formations of the sequence crop out few kilometres northeast of the study area.

The AAMC in the study area is strongly deformed and it crops out in several thrust slices, so that some of its formations have been tectonically removed (Fig. 2). The sequence is represented by Palaeozoic phyllitic and metavolcanic formations (‘Filladi inferiori’ and ‘Porfiroidi e Scisti Porfirici’), by Triassic metadolostone (‘Grezzoni’) and breccias (‘Brecce di Seravezza’) followed by Liassic pure and cherty marbles (‘Marmi’ and ‘Calcari selciferi’) and Cretaceous–Eocene phyllites (‘Scisti sericitici’). The upper part of the sequence is constituted of Cretaceous–Oligocene calcschists and chloritic marbles (‘Cipollini’) followed by Oligocene turbiditic metasandstones (‘Pseudomacigno’).

Dallan Nardi and Nardi [13] recognised in the study area, in the AAMC, different thrust slices. They attributed them to an intermediate palaeogeographic domain between the TN and the AAMC. By the way, Carmignani et al. [11] attributed the thrust slices to the AAMC, interpreting them as rootless plurikilometric F1 folds, developed during the main stacking of the tectonic units, newly deformed during the extensional tectonic phase.

Carmignani et al. [10] distinguished in the TN cropping out in the study area two deformation phases and correlate them to the deformation phases recognised in the AAMC [9].

3 Structural analysis

We present the results of the structural analysis carried out in the AAMC and in the overlying TN. Four ductile deformation phases have been recognized in the metamorphic sequence (D1–D2–D3–D4AAMC) and three in the Tuscan Nappe (D1–D2–D3TN) (Table 1).

3.1 Apuan Alps metamorphic complex

3.1.1 D1AAMC deformation phase

The first deformation phase produces a penetrative S1 foliation. It ranges from a continuous fine cleavage to a disjunctive spaced cleavage. It is well developed all over the metamorphic sequence, except in the Grezzoni Formation, because of its strong competence. According to Franceschelli et al. [15], S1 foliation developed under greenschist metamorphic conditions. Porphyroblasts of chloritoid grew post S1 foliation and pre S2. Isoclinal intrafolial folds are common. They belong to the classes IC and II [19]. F1 fold axes and intersection lineations between sedimentary bedding and S1 foliation trend NW–SE (Fig. 3). The L1 stretching lineation, trending NE–SW, is marked by elongated quartz and calcite grains and by quartz fibres in pressure shadows around pyrite crystals.

3.1.2 D2AAMC deformation phase

The second deformation phase is associated to the development of F2 folds and an S2 axial plane crenulation cleavage. In the less competent formations, such as Pseudomacigno, Scisti Sericitici and Cipollini, it produces tight asymmetric folds, with thickened hinges and stretched limbs. S2 foliation transposes the earlier foliation in the less competent layers. S2 foliation shows a flat attitude all over the study area and is often associated to pressure-solution (Fig. 3). F2 fold axes and intersection lineations are scattered (Fig. 3) and range from SSE-NNW plunging few degrees toward SSE, in the northern part of the study area, to nearly ENE–WSW plunging toward ENE in the southern part.

Ductile/brittle shear zones developed during the D2 deformation phase and they always show a tectonic transport toward the northeast.

3.1.3 D3AAMC deformation phase

It produces nearly parallel folds (class 1B; [19]), with upright attitude and interlimb angles ranging from 70 to 170°. The axial plane foliation (S3) is represented by a zonal crenulation cleavage. A3 fold axes trend NNW–SSE and plunge few degrees toward SSE (Fig. 3).

3.1.4 D1AAMC deformation phase

It produces nearly parallel folds (class 1B; [19]), with upright attitude and interlimb angles ranging from 120 to 170°. The axial plane foliation is represented by a spaced crenulation cleavage (S4). A4 fold axes trend nearly east–west and plunge few degrees toward either east or west (Fig. 3).

3.2 Tuscan Nappe

3.2.1 D1TN deformation phase

It is characterized by rare asymmetric folds, with variable interlimb angles and rounded fold hinges. F1 folds belong to the class 1C [19] and their axial planes moderately dip toward the southwest. F1 fold facing is toward the north-east. S1 axial plane foliation is the most prominent structural element associated to the D1 phase and ranges from a penetrative foliation (slaty cleavage) to a spaced disjunctive cleavage. In the calcareous rocks, it is associated to solution-transfer deformation mechanism. The dynamic recrystallisation of quartz, albite, calcite, illite and oxides on S1 foliation confirms the very low-grade metamorphic environment [12]. S1 foliation shows an overall change in strike from N110E to N170E in the study area (Fig. 3). The trend of A1 axes and intersection lineations is scattered from N100E to N170E and the plunge is nearly 30° toward the SE (Fig. 3). Top-to-northeast brittle–ductile shear zones and thrusts developed during this tectonic phase.

3.2.2 D2TN deformation phase

This is the prominent folding phase recognised in the Tuscan Nappe; it produces mappable folds. F2 folds show interlimb angles varying from 30 to 70°, rounded hinges and are referable to classes 1B and 1C [19]. F2 axial planes steeply dip toward east, indicating a west vergence for the F2 folds. The S2 axial plane foliation ranges from a zonal to a discrete crenulation cleavage.

3.2.3 D3TN deformation phase

D3 deformation phase produces 1B class open upright folds (with interlimb angles major than 70°). A3 fold axes trend nearly east–west and shallowly plunge eastward (Fig. 3). A spaced crenulation cleavage is observable in the fold hinges.

Collapse folds and low- to high-angle normal faults, related to extensional tectonics at upper crustal levels, are the last recognised structures [10].

3.3 Tectonic boundary

The tectonic boundary between AAMC and TN is exposed in the central part of the study area and in some tectonic windows (Fig. 2). It is marked by cataclasites and breccias, associated with low-angle faults. Cataclasite is constituted by fragments coming from the underlying metamorphic sequence, showing two penetrative foliations. The first one is a penetrative slaty cleavage and the second one is a crenulation cleavage with the same features as the deformations observed in the Scisti sericitici and Pseudomacigno. So the cataclasites should have been developed after the D2AAMC. The cataclasite shows brittle behaviour, contrasting with the ductile deformation in the AAMC; this suggests that the contact developed in the later stages.

The tectonic boundary between the TN and AAMC in the southeastern termination of the massif shows a change of orientation from north–south to nearly east–west and dip to the east and to the south (Fig. 2). This is due to folding by the two last deformation phases (D3 and D4AAMC and D2 and D3TN).

4 Discussion

Structural analysis revealed that the AAMC recorded two penetrative ductile deformation phases, followed by two later phases, due to continuing compression, but with minor shortening. On the contrary, the TN recorded only one penetrative ductile deformation followed by two later deformations (Table 1). The latest deformations are shared with the underlying AAMC and affect the tectonic boundary of the two units (Fig. 2; Table 1). The later (post D2AAMC) superposition of the TN onto the AAMC is also supported by the presence of polydeformed clasts inside the cataclasites; breccias developed at the tectonic boundary.

However, Carmignani and Kligfield [9] explain the presence of polydeformed clasts in the breccia by a syn-D2 extensional reactivation of a D1 thrust. Though, we have to stress that the tectonic transport in the study area is opposite with respect to the transport towards the southwest of extensional tectonics suggested by Carmignani and Kligfield [9].

The northeastern sense of movement could be in agreement with the sense of transport of the post-collisional extensional tectonics envisaged by Jolivet et al. [16]. The extensional interpretation of the contact is mainly based by these authors on the criteria of the superposition of the less metamorphic unit (TN) over the more metamorphic one (AAMC). As a matter of fact, the maximum pressure and temperature reached by TN are lower with respect to the underlying units that are underthrust more deeply [16]. As a consequence, whatever the compressive or extensional nature of the tectonic contact is, the difference in the metamorphic grade between the tectonic units cannot be indicative of the tectonic setting of the contact without other structural and kinematic evidences.

The two tectonic units exhibit a different structural evolution in the earlier stages of deformation (D1 and D2AAMC and D1TN; Table 1). The difference is highlighted also by the different metamorphic conditions. The metamorphic environment of the penetrative deformations in the AAMC and TN is different [15,16]. The two tectonic units, now tectonically coupled, exhibit a different deformation history; their coupling happened in later stages, but before the onset of the later folding phases, as their tectonic contact is folded by the D2TN and the D3AAMC.

It is important to stress that the main metamorphic event, related to the growth of kyanite and chloritoid in the Massa Unit and chloritoid in the AAMC, is regarded as post-D1 and pre-D2 [5] or pre- and syn-D2 [15]. The main consequence, as already pointed out by Boccaletti and Gosso [5], is that the superposition of the TN must have occurred after the metamorphic peak of the AAMC, i.e. post-D2AAMC. At a larger scale, the interposition of the more metamorphic Massa Unit [15,16] between TN and AAMC, in the western part of the massif (Fig. 1), supports the hypothesis according to which the superposition of the TN happened when a large part of the exhumation of the metamorphic units and the related deformation had been already realised.

5 Conclusions

Compared structural analysis in the TN and AAMC highlights a different tectonic history of the two tectonic units. Whereas the AAMC shows the presence of two ductile penetrative deformation phases, the TN records only one penetrative D1 deformation phase. The two tectonic units shared two later systems of folds affecting their tectonic contact. We propose that the superposition of the TN occurred post-D2 AAMC. This is also confirmed by the clasts of the metamorphic sequence found in the tectonic breccias, showing two ductile deformation phases before their involvement in the cataclasite.

The available data on metamorphism of the TN, MU and AAMC support this interpretation and suggest that the superposition of the TN over the MU and AAMC marked a later stage in the exhumation and in the tectonic evolution of the metamorphic units.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by CSGSDA, CNR, Pisa and funds from the University of Pisa. The authors thank an anonymous reviewer who improved the manuscript and D. Iacopini for his help with the French text.