Version abrégée

Une nouvelle campagne de cartographie du mont Parnon (Péloponnèse centro-oriental, Grèce) a montré qu'une épaisse série de type flysch, appelée unité de Glypia [21], surmonte les unités alpines de Tripolis et du Pinde. Ce flysch est principalement composé d'alternances de pélites, de grès grossiers et d'intercalations de calcaires marneux ou microbréchiques. Quelques fossiles ont prouvé qu'il s'agissait de dépôts du Tertiaire.

Des blocs exotiques se rencontrent fréquemment dans la matrice de l'unité de Glypia. Ils appartiennent généralement au Crétacé supérieur et ont une lithologie variée : calcaires aussi bien néritiques que pélagiques, brèches dolomitiques, radiolarites ou laves basaltiques. Quelques blocs de Permien fossilifère, qui mesurent jusqu'à 1,5 m3, sont également présents. Le microfaciès décrit ici a fourni une quarantaine d'espèces différentes d'algues, pseudo-algues, petits foraminifères et fusulines.

L'association est caractérisée par trois taxons (Fig. 2) : Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis, Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis et Colaniella aff. minima. La microflore algaire correspond à celle du niveau d'Argolide [25] et à celle des calcaires à Bellerophon de l'Italie ou de l'ex-Yougoslavie, du Montenegro notamment [14]. Parmi les pseudo-algues, les Tubiphytes observés affirment leurs affinités avec des foraminifères porcelanés.

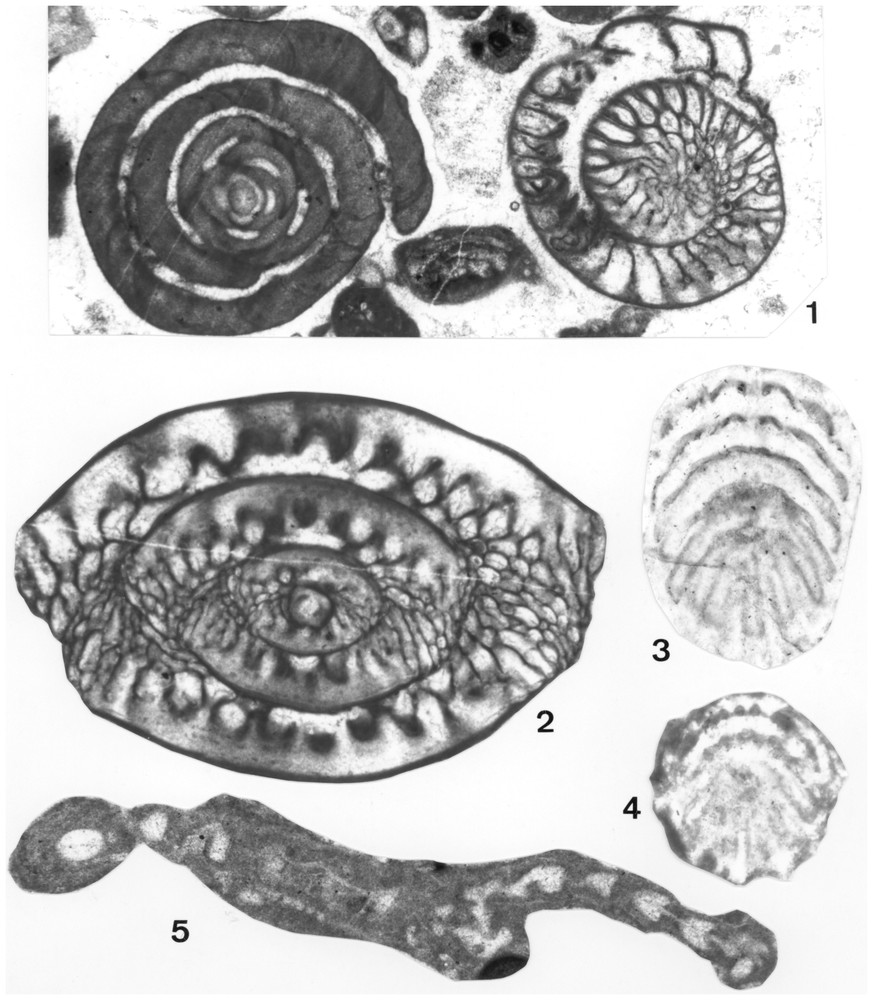

Main microfossils from the Late Wuchiapingian of Mount Parnon, Greece. 1: Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis (Wang and Sun, 1973), transverse section (left) with Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis Chediya in [9], subtransverse section (right) and the general aspect of the microfacies (a bioclastic and peloidal grainstone). Sample Phi 38b.×30; 2: Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis Chediya in [9], axial section, showing the proloculus, the four whorls, the septal folding and the septal pores. Sample Phi 38b.×40. 3–4: Colaniella aff. minima Wang, 1966; 3, subaxial section, sample Phi 38a.×75; 4: oblique section ; sample Phi 38a.×75; 5: Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov, 1956, longitudinal section, with three stages of development – proloculus (right), a relatively regular Nodophthalmidium-like (right), and irregular, i.e. typical stage (centre and left). Sample Phi 38b.×75.

Principaux microfossiles du Wuchiapingien supérieur du mont Parnon, en Grèce. 1 : Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis (Wang et Sun, 1973), section transverse (à gauche), avec Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis Chediya in [9], section subtransverse (à droite) et aspect général du microfaciès (un grainstone pelloı̈dal et bioclastique). Échantillon Phi 38b.×30 ; 2 : Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis Chediya in [9], section axiale montrant le proloculus, les quatre tours de spire, les cloisons plissées et les pores septaux. Échantillon Phi 38b.×40. 3–4 : Colaniella aff. minima Wang, 1966 ; 3 : section subaxiale, échantillon Phi 38a.×75 ; 4 : section oblique, échantillon Phi 38a.×75 ; 5 : Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov, 1956, section longitudinale, avec trois stades de développement : proloculus (à droite), suivi d'un stade Nodophtalmidium assez régulier (à droite), puis d'un stade irrégulier, c'est-à-dire typique (au centre et à gauche). Échantillon Phi 38b.×75.

L'application des anciens critères biostratigraphiques des auteurs russes [3,9–11,15,16] conduirait à conclure à un niveau du Midien terminal (=Capitanien terminal des nouvelles échelles). Nous préférons toutefois suivre l'avis de Davydov et al. [5] et attribuer l'association au Djoulfien supérieur (ou, selon la terminologie actuelle, au Wuchiapingien supérieur). En conséquence, dans les stratotypes de Transcaucasie, contrairement aux anciennes propositions [10], ce serait la zone IX, du Djoulfien supérieur, qui serait l'équivalent de la biozone à Shindella, plutôt que la zone VII du Midien terminal.

Deux arguments, tirés des séries de Grèce, confirment cette attribution. D'abord, la nouvelle association s'avère un peu plus évoluée que celle que nous avions datée du Djoulfien inférieur en Argolide [25], puisque des Colaniella remplacent les Pseudowanganella, et que des Shindella et des Nanlingella primitives prennent la place des Pseudodunbarula (Fig. 3). Ensuite, la formation d'Episcopi, à Hydra, contient des conodontes du Wuchiapingien supérieur [6,13]. Cependant, pour préciser les corrélations, les foraminifères de cette Formation devront être révisés, car ils forment pour l'instant un continuum daté du Capitanien/Midien au Changxingien/Dorashamien, dans lequel les « Palaeofusulinae » des auteurs [2,6] désignent sans doute plusieurs taxons différents de Palaeofusulininae, dont Shindella et Nanlingella.

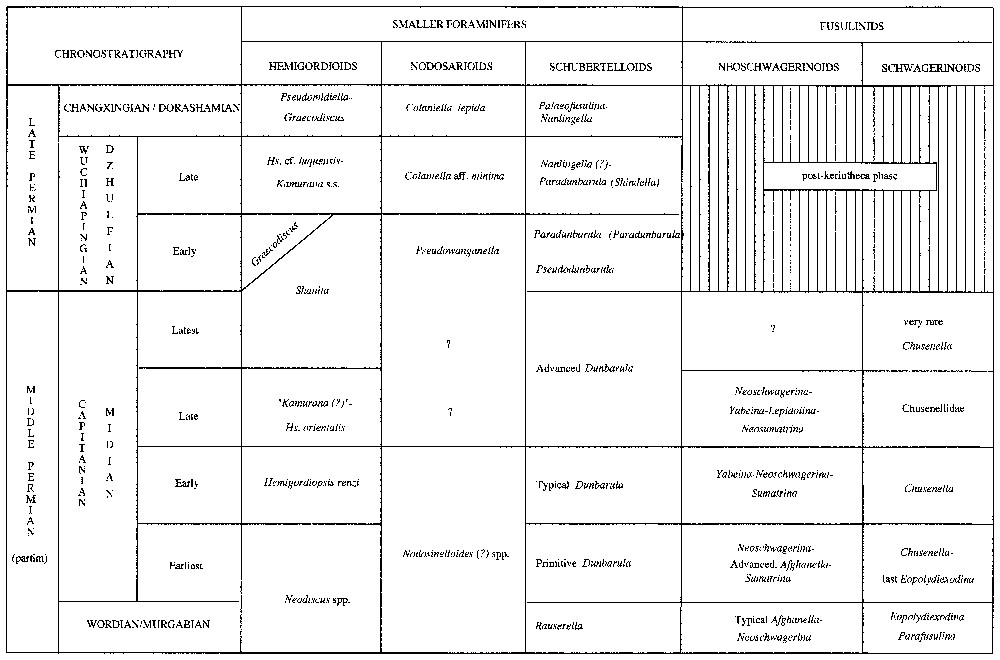

Comparative table of the main foraminifers of the Middle–Late Permian in the Tethyan basins from Greece to southern China (compilation of several published and unpublished data, especially from Afghanistan, Tunisia, Oman and Cambodia; Vachard et al., work in progress).

Tableau comparatif des principaux groupes de foraminifères du Permien moyen et supérieur dans les bassins paléotéthysiens de la Grèce à la Chine du Sud (compilation de différentes données publiées ou inédites, provenant en particulier d'Afghanistan, Tunisie, Oman et Cambodge ; Vachard et al., travail en cours).

L'origine des olistolithes calcaires de l'unité de Glypia est à rechercher dans la nappe de l'unité Subpélagonienne : sur l'ı̂le d'Hydra [2,6,13,18,19], sur les ı̂lots de Karavia [22,23] ou en Argolide [25]. Si les affleurements de ces calcaires semblent si réduits en Grèce, c'est peut-être parce qu'ils ont été activement démantelés et remaniés dans différentes séries du Mésozoı̈que et du Cénozoı̈que.

Enfin, les affinités paléobiogéographiques des marqueurs, notamment celles de la fusuline Paradunbarula (Shindella), sont très étroites (jusqu'au niveau spécifique) avec le Pamir du Sud-Est et la Chine du Sud. De telles relations, difficilement compatibles avec de trop larges océans téthysiens, sont plus aisément explicables par des reconstitutions de type Pangée B [4].

1 Introduction

The discovery of reworked Late Permian olistolites on Mount Parnon (Peloponnesus, Greece) has three main implications: (i) they confirm the frequent reworking of the limestones of this age in Mesozoic and Cainozoic Formations of Greece, (ii) they document a little known substage of the Late Permian: the Late Wuchiapingian/Dzhulfian, (iii) they constitute a new evidence for the strong affinities of the Greek microfaunas with those of eastern Tethys, such as Pamir and southern China.

2 Geological setting

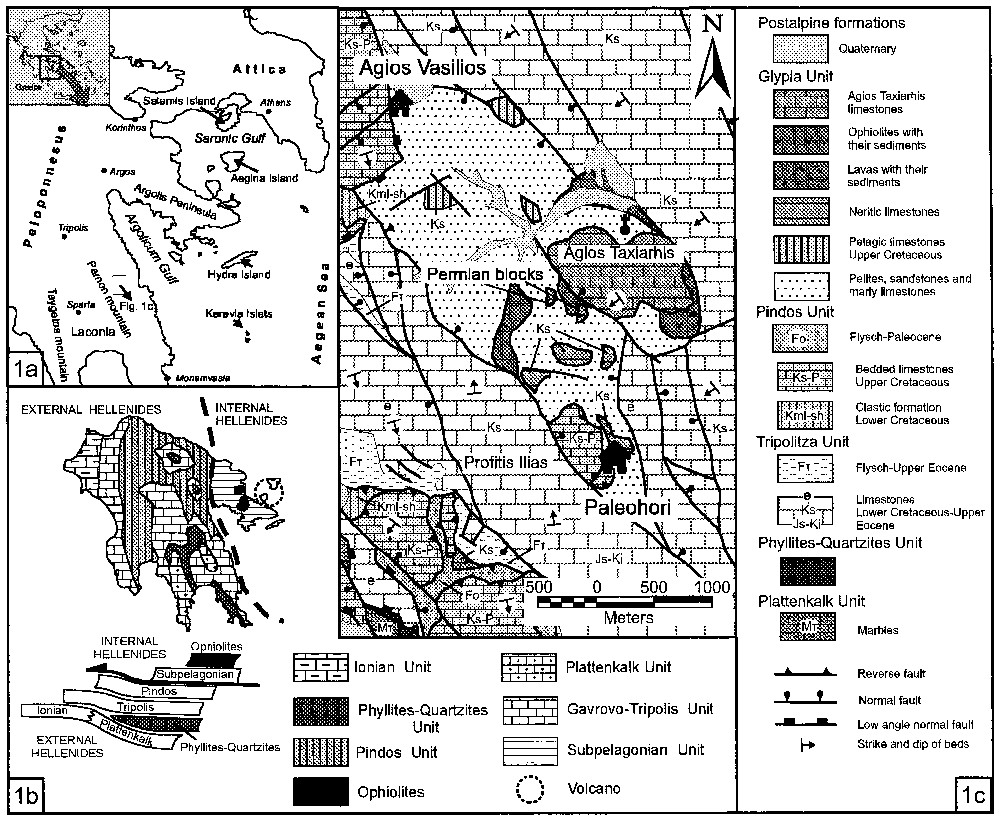

New investigations in the Mount Parnon range (central eastern Peloponnesus, Greece) revealed the existence of a clastic flysch-type formation over the alpine units of Tripolis and Pindos, named Glypia unit [21]. This Glypia flysch is composed of alternations of pelitic horizons, coarse-grained sandstones and marly or microbrecciated limestones. Fossils found in some marly limestone intercalations were identified to be of Tertiary age [21].

The occurrence of exotic blocks floating within the matrix of Glypia unit is relatively common (Fig. 1). These blocks may belong to carbonate formations of Late Cretaceous age of either pelagic of neritic character, dolomitic breccias, radiolarites, basaltic lavas accompanied by pelites and microbrecciated limestones of Late Cretaceous age and serpentinites along with greenish pelites, sandstones and microbrecciated limestones of unknown age.

Location sketch maps of the Mount Parnon Range (Peloponnesus, Greece). a: Location in Greece. b: Geological and structural interpretations. c: Stratigraphic and structural column.

Cartes géologiques schématiques du mont Parnon (Péloponnèse, Grèce). a : Localisation en Grèce. b : Interprétations géologiques et structurales. c : Colonne stratigraphique et structurale.

Late Permian blocks up to 1.5 m3 occur also. They consist of grey to whitish, richly fossiliferous limestones. This paper describes the most interesting microfacies, and analyses the biostratigraphic and palaeogeographic consequences of this discovery.

3 Previous work

Middle and Late Permian of Greece are rather poorly known and poorly illustrated, except for the Wordian, i.e. Murgabian [2,6,22,23,26, with bibliography], although the major part of this stage is probably more accurately Capitanian/Midian in age, according to the subsequent criteria of Leven [11]. The presence of Midian is mentioned in Hydra in the lower part of the Episkopi Formation [2,6], and may be also supposed in Laconia [24, re-interpreted]. The Wuchiapingian constitutes the middle part of the Episkopi Formation [2,6,13], where it is subdivided into Early and Late Wuchiapingian by conodonts [6,13]. The Early Wuchiapingian/Dzhulfian is also dated by foraminifera, reworked within Jurassic breccias in Argolis [25]. Finally, the Changxingian/Dorashamian is characterised by various foraminifera: Palaeofusulina, Globivalvulinoides, Baudiella, Paradoxiella, Colaniella in Attica [1,27], and in the upper part of the Episkopi Fm. [2,6], which contains true Palaeofusulina [6].

We document and illustrate the first regional Late Wuchiapingian association of foraminifera, algae, and pseudo-algae.

4 Microfacies analysis

The most interesting microfacies of Late Permian olistolites is a bioclastic grainstone with two generations of cements (palissadic and coarsely granular). The assemblage is rich in algae, corresponding to an agitated environment in the photic zone, probably at a depth of 5–10 m, in a tropical carbonate ramp. The microfossils are composed of:

- – metazoan remains: gastropods (including Bellerophontoidea), bivalves, crinoids, bryozoa, calcisponges;

- – algae: Parachaetetes sp., Permocalculus sp., Gymnocodium bellerophontis (Rothpletz) Pia, Eugonophyllum sp., Mizzia cf. yabei (Karpinsky), Macroporella apachena Johnson, Salopekiella sp., Likanella (?) sp., Atractyliopsis lastensis Accordi;

- – pseudo-algae: Tubiphytes obscurus Maslov (morphotypes similar to the foraminifer Nodophthalmidium; Fig. 2.5), Claracrusta calamistrata Vachard, Eflugelia johnsoni (Flügel) Massa and Vachard, Ungdarella (?) sp.;

- – smaller foraminifera: Spireitlina conspecta (Reitlinger), Neoendothyra sp., Tetrataxis conica (Ehrenberg), Abadehella sp., Palaeotextularia sp., Climacammina cf. valvulinoides Lange, Cribrogenerina sp., Globivalvulina graeca Reichel, G. vonderschmitti Reichel, Sengoerina cf. argandi Altiner, Pseudovermiporella ex gr. nipponica (Endo in Endo and Kanuma), Neodiscus sp., Multidiscus ex gr. padangensis (Lange), Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis (Wang and Sun) (Fig. 2.1), Agathammina sp., Calvezina (?) sp., Pachyphloia sp., Nodosaria (?) sp., Colaniella aff. minima Wang (Figs. 2.3 and 2.4).

- – fusulinids: Sphaerulina zisonzhengensis Sheng, Reichelina sp., Schubertella sp., Codonofusiella sp., Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis Chediya in Kotlyar et al. (Figs. 2.1 and 2.2), Nanlingella (?) sp., abraded Neoschwagerina sp.

5 Origin of olistolites

The origin of these Late Wuchiapingian olistolites must be sought within the nappe of Subpelagonian unit where relatively similar assemblages have been described within its Permian–Triassic basal successions in Hydra island [2,6,13,18,19] and Karavia islets [22,23], as well as within Jurassic breccias in Argolis [25]. The foraminiferal and algal composition of the middle part of the Episkopi Formation in Hydra, previously listed [2,6], might be interpreted as nearly identical. Colaniella ex gr. minima is mentioned, the group of ‘Hemigordiopsis renzi’ contains probably some H. cf. luquensis, and ‘Palaeofusulina sp.’ of the Episkopi Fm. might correspond partially to Paradunbarula (Shindella). Compare, for instance, our Shindella (Fig. 2.2) with Palaeofusulina nana Likharev, recently re-figured [16, pl. 7, Fig. 11]. Only the septal folding is stronger in this primitive Palaeofusulina of the Changxingian, finally very similar to the advanced Shindella of the Glypia unit.

6 Biostratigraphic importance

Three markers generally isolated are here associated: Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis, Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis and Colaniella aff. minima. According to the classical Russian criteria [3,9–11,15,16], generally adopted in western Europe [2,6–8] age could be supposed to be Late Capitanian/Midian. Nevertheless, a Late Dzhulfian dating is more justified for five reasons: (a) the Shindella zone is placed in the Late Dzhulfian by Davydov et al. [5]; (b) the beds containing Shindella in Pamir [9] are located between Early Midian and Early Triassic deposits, and are not typically Late Midian; (c) in Greece, a relatively similar assemblage, dated Early Dzhulfian [25], is actually more primitive because it includes Pseudodunbarula and Pseudowanganella and not Paradunbarula (Shindella) and Colaniella, more advanced phylogenetically (Fig. 3); (d) Late Wuchiapingian conodonts are known in the middle part of the carbonate Episkopi Formation in Hydra [6,13]; (e) two taxa of our assemblage correspond respectively to atypical forms of Nanlingella, and to a Sengoerina relatively similar by its wall structure to Paradagmarita flabelliformis Zaninetti et al., even if true Nanlingella and Paradagmarita are considered as Changxingian microfossils.

Compared to different data of Tethyan foraminifera (Vachard et al., work in progress), this Late Wuchiapingian assemblage suggests six preliminary biostratigraphic remarks: (a) the Shindella biozone is definitively Late Wuchiapingian in age, from Greece to China; (b) among the subdivisions of the stratotypic Dzhulfian in Transcaucasia, in the absence of Shindella, the Shindella biozone can probably be correlated with the zone IX (Late Dzhulfian) and not with the zone VII (Latest Midian), as proposed [10]; (c) the genus Hemigordiopsis is present in the Late Dzhulfian, contrary to the opinion of Pronina [16]; many of these Dzhulfian Hemigordiopsis are probably erroneously identified with Neodiscus, Kamurana or Pseudobaisalina; (d) the first appearance of Colaniella is in the Late Dzhulfian, contrary to previous proposals [4,7,12]; this fact confirms entirely the reworking reported from Italy [8]: Colaniella cannot biologically coexist with Afghanella, which disappears in the Earliest Capitanian/Midian (Fig. 3), similarly the unique abraded section of Neoschwagerinid observed in our material is reworked (Fig. 3); (e) although ancestor of Shanita, Hemigordiopsis can survive this latter (Fig. 3); (f) Graecodiscus, although absent of the investigated material, is known from the Early Dzhulfian [25] (Fig. 3) to the Late Dorashamian [17].

7 Palaeogeographic consequences

The assemblage is also palaeobiogeographically significant, and it testifies similarities between Greece, southeastern Pamir, and southern China.

Paradunbarula has been described in Anatolia (Turkey) [20], the subgenus Shindella is identified in southeastern Pamir and southern China [9], but lacks in Transcaucasia [10]. Hemigordiopsis luquensis (Wang and Sun) is a species from southern China [28]. Its probable synonym H. orientalis (Wang and Sun) [28] is found in southern China and Transcaucasia [10,15], probably in Early Midian beds [10,12]. Our material (Fig. 2.1) is relatively atypical, because it displays fewer whorls (4–5 versus 5–7) for the same diameter, but is evidently identical to a taxon described in Montenegro [14, pl. 5, Figs. 1–4]: under the erroneous name of H. renzi]. The most primitive Colaniella were mentioned in Pamir and southern China [3,7].

Similarly, the recently described Early Changxingian fusulinid genus Baudiella [1] is only known from two localities: in Greece (Salamis Island) and southern China (Nanjing area).

Consequently, the similarities between the Greek microfauna with that of southern China and southeastern Pamir confirm palaeogeographic reconstructions that indicate a closer location of these three geographic units. The Palaeotethys of the time was probably narrow and its southern shallow carbonate shelf extended in continuity from Greece to southeastern Pamir and southern China, via Turkey and southern Iran, and was situated in the same tropical or subequatorial latitude. These data are congruent with a Pangea B, similar to that suggested by Crasquin et al. [4].

8 Conclusions

The origin of the Late Wuchiapingian (Late Permian) olistolites found in the Glypia Tertiary flysch must be sought in regions located to the east of the Mount Parnon and in units that were more internal to Pindos Unit. The islets of Karavia in the Argolis Gulf, and the Episkopi Formation in the Hydra Island, display the largest outcrops of this age. Permian pebbles described in Jurassic breccias in Potami Formation in Argolicum Peninsula may also be the origin of these blocks.

Three markers generally not co-occurring are locally associated: Paradunbarula (Shindella) shindensis, Hemigordiopsis cf. luquensis and Colaniella aff. minima. Therefore, in the range-biozone of Shindella, correctly dated as Late Wuchiapingian/Dzhulfian by Davydov et al. [5], coexist the first Colaniella with the last Hemigordiopsis (Fig. 3).

The similarities of the Greek microfauna with that of southern China and southeastern Pamir are incompatible with a larger Palaeotethys, but support the palaeogeographic reconstructions that indicate a close location of these geographic units (Pangea B).