Version abrégée

1 Introduction

Les éolianites affleurant en fenêtre au sein de l'erg du désert de Namibie contiennent des restes de mammifères et des oeufs de ratites [21,27–30]. Le δ13C a été mesuré sur ces coquilles, pour déterminer si la biosphère continentale a enregistré les changements climatiques des derniers millions d'années, liés à la formation du Namib.

2 Le carbone 13 dans la biosphère continentale

Les δ13C varient de −26,5‰ pour les plantes dites en C3 à −12,5‰ pour celles en C4. Par rapport aux plantes en C3, la photosynthèse de type C4 présente un meilleur rendement pour les basses pressions de CO2 [6]. La teneur en CO2 de l'atmosphère est donc un facteur au moins aussi important que l'humidité ou la température pour le développement des plantes en C4 [6,22].

3 Le rapport isotopique du carbone dans les coquilles d'œufs de ratites

Le δ13C des coquilles des autruches actuelles présentent un enrichissement de 16,2‰ par rapport à celui de l'alimentation [34]. Pour les fossiles, nous considérons que leur physiologie n'a pas changé depuis le Miocène. Le δ13C de leur nourriture est fonction des proportions consommées de plantes en C3 et en C4 [13]. En tenant compte de la variabilité (±3‰) des δ13C de chaque type de plantes (lié à l'aridité, aux précipitations [7,9–11]), on peut donc calculer le pourcentage de chaque type consommé par individu : et . Ces relations ont été vérifiées en élevages à nourriture contrôlée [34] ; toutefois, dans leur milieu naturel, ces animaux présentent une préférence pour les plantes en C3 [12], qui introduit un biais dans la reconstitution des paléoenvironnements.

4 Résultats isotopiques

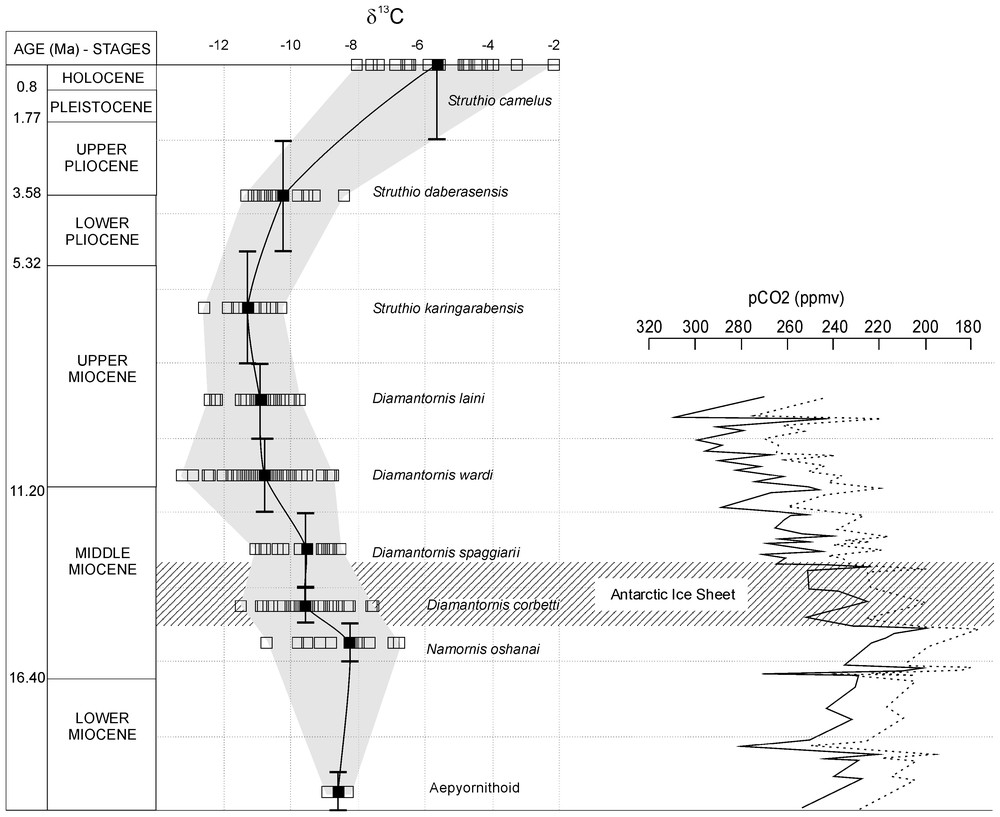

Les fluctuations du δ13C (Tableau 1 et Fig. 2) ont été établies pour les 20 derniers millions d'années (l'âge des coquilles de type Aepyornithoı̈de d'Elisabethfeld est estimé à 19–20 Ma par les mammifères). Le δ13C moyen est de −8,6‰ au Miocène inférieur. Au Miocène moyen, il augmente d'abord légèrement (−8,25‰ dans la biozone à Namornis oshanai, 15–16 Ma), puis chute en deux étapes : (1) vers 15 Ma, il diminue de −1,31‰ entre les biozones à N. oshanai et à D. corbetti, où le δ13C moyen est alors de −9,56‰, puis reste ensuite stable (−9,51‰) durant la biozone à D. spaggiarii (12–14 Ma) ; (2) vers 12 Ma, une nouvelle diminution de −1,25‰ survient entre les biozones à D. spaggiarii (12–14 Ma) et à D. wardi (10–12 Ma), où le δ13C moyen atteint −10,76‰. Durant le début du Miocène supérieur, le δ13C se stabilise (−10,89‰ dans la biozone à D. laini, 8–10 Ma), puis diminue légèrement, pour atteindre −11,26‰ dans la biozone à S. karingarabensis (Miocène supérieur–Pliocène basal, 8–5 Ma). Durant la biozone à S. daberasensis (2–5 Ma), le δ13C remonte de près de 1‰, pour atteindre une valeur de −10,23‰ au cours du Pliocène. Enfin, les oeufs actuels (S. camelus) présentent un δ13C de −5,62‰.

Eggshell carbon isotopic ratios from the different studied sites.

δ13C des coquilles de ratites pour l'ensemble des sites étudiés.

Ratite eggshell δ13C evolution during the Neogene and Quaternary. Correlation with atmospheric CO2 concentration estimates during the Miocene in the southern hemisphere. Modified from Pagani [16]. Time scale from Berggren and Cande [1,2].

Variations au cours du Néogène et du Quaternaire du δ13C des coquilles de ratites. Corrélation avec les variations du CO2 atmosphérique durant le Miocène dans l'hémisphère sud. Modifié d'après Pagani [16]. Échelle de temps d'après Berggren et Cande [1,2].

5 Discussions

5.1 Des plantes en C4 présentes en Namibie dès le Miocène inférieur ?

Pour chaque période, il est possible de déterminer un δ13C théorique des coquilles, qui tienne compte à la fois du régime alimentaire et de la variabilité du δ13C des plantes [11] :

5.2 Conséquences paléoclimatiques

Si la concentration du CO2 atmosphérique est, à long terme, le paramètre majeur pour le développement des plantes en C4, les conditions climatiques (température et régime de pluies durant la phase de croissance [26]) jouent également un rôle.

5.2.1 Au Miocène inférieur–moyen

Les données paléontologiques de Namibie [19] indiquent, pour le Miocène basal, un climat subtropical, plus chaud et plus humide qu'actuellement. Ces conditions perdurent au moins jusqu'à 17 Ma [20]. Au Miocène moyen se produit une aridification de la zone côtière [33], qui se marque par les premiers dépôts éoliens (biozone à N. oshanai, 15–16 Ma) à Awasib.

5.2.2 Du Miocène supérieur à l'Actuel

Le δ13C des coquilles augmente de 1‰ au cours du Miocène supérieur et du Pliocène, puis de près de 4,5‰ entre le Pliocène et l'Actuel (Fig. 2). Malgré une préférence pour les plantes en C3 [12], le δ13C moyen des œufs des autruches actuelles correspond à un régime composé seulement à 60–65 % de ces plantes. Par contre, nos données suggèrent une présence plus importante de plantes en C3 au Miocène supérieur. Le Pliocène apparaı̂t donc comme une période charnière, où les plantes en C4 prennent alors une place prépondérante dans certains écosystèmes continentaux [3,15,23,24].

Après d'importantes fluctuations au cours du Quaternaire [14], les concentrations actuelles du CO2 dans l'atmosphère (350 ppmv) sont proches de celles du Miocène supérieur (320 ppmv). Comme le climat, au niveau du Namib, était moins aride qu'actuellement (traces de racines et développement de paléosols à Awasib), la température et les régimes des pluies paraissent être les principaux facteurs responsables de l'augmentation des plantes en C4 dans le système désertique, entre le Miocène supérieur et l'Actuel.

6 Conclusions

L'évolution du δ13C des coquilles met en évidence une modification du régime alimentaire des ratites, indiquant une variation du pourcentage relatif des plantes en C3 et en C4 dans l'écosystème du Namib. Les faibles concentrations en CO2 atmosphérique au Miocène inférieur semblent être le paramètre majeur expliquant la présence de plantes C4 dans le milieu. Durant le Miocène moyen et terminal, les conditions régionales de température et de précipitations exercent ensuite un effet de plus en plus important sur la composition de l'écosystème namibien.

1 Introduction

It is classically thought that the causes of the coastal deserts (Namibia and Chile–Peru) are: (1) the development of the Antarctic Ice Sheet, which reinforced the high pressure belt under the Tropic of Capricorn, (2) the installation of cold currents along the western coasts of continents (i.e., Benguela Current) and (3) the associated upwellings. In Namibia, ancient aeolanites have yielded ratite eggshells and fossil mammals, leading to a biostratigraphic scale from ca 20 Ma to Present [21,27–30] (calibrated by radiometric dates on volcanic rocks interlayered between fossiliferous beds of similar East African fauna [17,18]). This preliminary study aims at verifying whether the ratite eggshell δ13C could have recorded the Neogene climatic changes responsible for the formation of the Namib Desert.

2 Carbon-13 in the continental biosphere

Photosynthesis presents two basic biochemical cycles: the Calvin cycle alone is present in C3 plants, while C4 plants use the Hatch–Slack cycle. These two categories of processes lead to very different δ13C: −12.5‰ (±3‰) in C4 plants and −26.5‰ (±3‰) in C3 type. The variability is in relation with climatic factors as humidity, precipitations, temperatures, or light intensity [7–10]. The C4 photosynthetic process permits the concentration of the amount of intracellular CO2 by a factor of 10 to 20 times in the Kranz cell as compared to the quantity of CO2 present in the mesophyllian cell [5]. Therefore, C4 photosynthesis has a better efficiency when the atmospheric pressure of CO2 is low. In contrast, when the pressure of CO2 increases, the photosynthetic cycle in C3 plants is improved [6,22].

3 Carbon isotopic ratios in ratite eggshells

The egg cycle is relatively short (about 24 h). During the shell synthesis, the amount of Ca2+ in the blood increases. Specialised cells secrete the organic components that permit the precipitation of calcium ions, associated with carbonate ions (derived from metabolic CO2), to form the eggshell [31]. The δ13C eggshell is related to the diet of the birds [34]. The ostrich eggshells present enrichment in 13C relative to their diet:

| (1) |

For the fossils species, we assume that metabolic processes are unchanged since the Miocene. Being herbivores, the isotope ratios of their food is a function of the mixture between a diet composed of 100% of C3 plants, on the one hand, and of 100% of C4 plants, on the other hand [13]:

| (2) |

From Eqs. (1) and (2), we can deduce the percentage of C3 or C4 plants in the diet: (3)

Isotopic record reliability has been verified for domestic ostriches by experiments with controlled amounts of C3 and C4 plant diets [34]. However, in wild environment, these animals prefer C3 plants [12]. Thus, in ecosystems with 25 to 75% of C3 plants (South Africa), the eggshell δ13C correspond to a rate of 70 to 100% of the C3 plants ingested. Hence, dietary choice by the animals introduces a bias in the reconstruction of palaeoenvironments.

4 Choice and preparation of material

Fossil eggs were collected in the central and southern Namib Desert (Fig. 1): Karingarab, GP Pan and Rooilepel, all close to Oranjemund, Elisabethfeld, to the south of Lüderitz, and Awasib and Haiber Hill, both in the Namib–Naukluft Park.

Location of fossiliferous sites: Karingarab: (28°11′41.8″S/16°21′12.0″E), GP Pan (28°29′96.8″S/16°32′28.2″E), Rooilepel (28°17′99.6″S/16°35′53.1″E), Elisabethfeld (26°58′58.5″S/15°53′9″E), Awasib (site I: 25°18′28.7″S/15°38′43.6″E; site II: 25°22′48.4″S/15°34′42.1″E) and Haiber Hill (site I: 25°37′14.5″S/15°39′34.9″E; site II: 25°40′16.9″S/15°39′68.5″E).

Localisation des sites fossilifères : Karingarab : (28°11′41.8″S/16°21′12.0″E), GP Pan (28°29′96.8″S/16°32′28.2″E), Rooilepel (28°17′99.6″S/16°35′53.1″E), Elisabethfeld (26°58′58.5″S/15°53′9″E), Awasib (site I : 25°18′28.7″S/15°38′43.6″E ; site II : 25°22′48.4″S/15°34′42.1″E) et Haiber Hill (site I : 25°37′14.5″S/15°39′34.9″E ; site II : 25°40′16.9″S/15°39′68.5″E).

Related to diagenetic alterations [4], the external and internal surfaces eggshells (low-magnesian calcite), which often present a bright cathodoluminescence, were cleaned by abrasion and then treated by ultrasound. Samples were extracted from the thickest parts of the shell (not eroded by the wind) and away from the pore complexes (which tend to be recrystallised). Comparison with previous ostrich eggshell data from Dauphin et al. [4] shows that the chosen sampling technique eliminates up to 95% of the diagenetic and allochtonous sediments. Isotope ratios were measured on a SIRA9/VG602 spectrometer. The analytical precision for carbon is of about 0.05‰.

5 Isotopic results

From isotopic values obtained for each eggshell species at the various sites (Table 1), it is possible to draw the δ13C fluctuation curve from 20 Ma up to present times (Fig. 2). Isotopic fluctuations are validated by the Student test (Table 1). The oldest eggshells (Aepyornithoı̈dea type) from Elisabethfeld are dated around 19–20 Ma (mammalian biochronology). The mean δ13C during the Early Miocene is −8.6‰ (Fig. 2). At the base of the Middle Miocene, it increases slightly (0.35‰) to reach −8.25‰ in the Namornis oshanai biozone (ca 16–15 Ma). During the Middle Miocene, the curve shows an important negative excursion by two steps. The first one occurs at ca 15 Ma, when the mean δ13C drops by −1.31‰ between the N. oshanai and D. corbetti biozones (‰). Then it remains stable (‰) during the D. spaggiarii zone (14–12 Ma). The second drop occurs at about 12 Ma (a diminution of −1.25‰) occurs between the D. spaggiarii and D. wardi zones (12–10 Ma), where the δ13C value reaches −10.76‰. The student test (Table 1) shows that the two Miocene δ13C drops are significant (t=3.92, α=0.05 and t=4.65, α=0.05). During the early part of the Late Miocene, the mean δ13C remains reasonably stable, around −10.89‰, in the D. laini biozone. It diminishes slightly (−0.37‰) to reach −11.26‰ during the S. karingarabensis biozone (Latest Miocene to Basal Pliocene; 8–5 Ma). During the S. daberasensis biozone (5–2 Ma), the δ13C increases nearly of 1‰ to reach −10.23‰ during the Pliocene. Finally, the mean δ13C obtained from modern ostrich eggs (S. camelus) is −5.62‰. Due to climatic differences between north and south outcrop localities, the variability of δ13C could be relatively large (±3‰) for the modern Namibian eggshells. Student tests (Table 1) valid the δ13C positive evolution from Pliocene to Recent (t=2.66, α=0.05 and t=10.19, α=0.05).

6 Discussion

6.1 C4 plants in Namibia ecosystems during the Early and Middle Miocene?

The evolution of eggshell δ13C could be interpreted in term of C3/C4 diet evolution from Eq. (3). Taking into account the δ13C variability of plant (±3‰), the diet of Early and Middle Miocene species (20–14 Ma), is made of 65 to 100% of C3 plants (most probable value 85%). The diminution of the δ13C occurring between 14 and 12 Ma leads to a 75 to 100% contribution of C3 plants (probable value: 95%). C3 plants reach 85 to 100% between 12 and 5 Ma (probable value: 100%). For modern Namibian ratites, a large proportion of C4 plants should be present in the food diet to explain the eggshell δ13C. C3 plants represent only between 45 and 85% (probable value 65%) of the diet. This estimation is in accordance with the modern Namibian ecosystem composition (30% of C3 plants [26]), in relation with the ostriches' dietary preference for C3 plants [12].

Numerous studies have shown that environmental parameters can influence the value of the δ13C of plants: aridity increases the δ13C value in C3 plants (0.33‰ per 100 mm decrease in precipitation, [32]). An increase of 100 ppm in atmospheric CO2 concentrations leads to a decrease of 2‰ in plant δ13C; the δ13C of atmospheric CO2 has also an impact [9]. In spite of these relationships, we should test if δ13C fluctuations in the Upper Tertiary could be explained by climatic variations without diet composition fluctuations. For this, we can use the equation proposed by Hatté and Antoine [11]:

| (4) |

Pre-industrial period parameters could be [CO2]0=280 ppmv, ‰, ‰ and Precip0=50 mm (mean value for the Namib desert). During the Neogene, in the absence of data, we have used the δ13C of pre-industrial period as δ13C[CO2]. The Miocene atmospheric CO2 concentrations during the Miocene could be estimated on the basis of Pagani data [16]. From the beginning of Early Miocene (24 Ma) to Middle Miocene (16–15 Ma), the concentration has first diminished by 110 ppmv, before increasing after 15–14 Ma (220 ppmv, Fig. 2). Related to the installation of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (as recorded by an excursion of +1‰ in planctonic foraminifera δ18O at about 14 Ma), this increase continues until 10 Ma (280 ppmv). Nowadays, in Namibia, annual precipitation means are comprised between 150–400 mm in grassland savannah regions and between 100–150 mm in semi-arid regions; they are lower than 50 mm in arid areas.

From Eq. (4), we can calculate a theoretical eggshell δ13C for different rates of precipitations (Table 2). For modern Namibian species, the use of Eq. (4) (Table 2) confirms that with the actual rate of precipitation (<50 mm), the eggshell δ13C could not correspond to a 100% C3 diet. A participation of C4 plant of the order of 40% is needed (see above).

Calculation of the δ13C of ratite eggshells, for a given diet, according to different precipitation rates. Bold numbers correspond to the compatible values for the diet suggested.

Calcul du δ13C des coquilles de ratites, pour un régime donné, en fonction de différents taux de précipitation. Les chiffres en gras correspondent aux valeurs compatibles pour le régime proposé.

| Modern; [CO2] = 320 ppmv | Upper Miocene (10 Ma); [CO2] = 290 ppmv | |||

| Precip. (mm) | Diet = 60% C3 & 40% C4 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) | Diet = 100% C3 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) |

| 0 | −24.55 | −8.35 | ||

| 50 | −22.2 | −26.2 | ||

| 100 | −27.85 | |||

| 150 | −29.5 | −13.3 | ||

| 200 | −31.15 | −14.95 | ||

| 250 | −32.8 | −16.6 | ||

| 300 | −34.45 | −18.25 | ||

| 350 | −36.1 | −19.9 | ||

| 400 | −37.75 | −21.55 | ||

| Middle Miocene (15 Ma); [CO2] = 220 ppmv | ||||

| Precip. (mm) | Diet = 100% C3 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) | Diet = 85% C3 & 15% C4 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) |

| 0 | −23.15 | −6.95 | −21.05 | −4.85 |

| 50 | −24.8 | −22.7 | −6.5 | |

| 100 | −26.45 | −10.25 | ||

| 150 | −28.1 | −11.9 | ||

| 200 | −29.75 | −13.55 | −27.65 | −11.45 |

| 250 | −31.4 | −15.2 | −29.3 | −13.1 |

| 300 | −33.05 | −16.85 | −30.95 | −14.75 |

| 350 | −34.7 | −18.5 | −32.6 | −16.4 |

| 400 | −36.35 | −20.15 | −34.25 | −18.05 |

| Lower Miocene (18 Ma); CO2 = 240 ppmv | ||||

| Precip. (mm) | Diet = 100% C3 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) | Diet = 60% C3 & 40% C4 | δ13C eggshell (per mill) |

| 0 | −23.55 | −17.95 | −1.75 | |

| 50 | −25.2 | −19.6 | −3.4 | |

| 100 | −26.85 | −10.65 | −21.25 | −5.05 |

| 150 | −28.5 | −12.3 | −22.9 | −6.7 |

| 200 | −30.15 | −13.95 | −24.55 | |

| 250 | −31.8 | −15.6 | −26.2 | −10 |

| 300 | −33.45 | −17.25 | −27.85 | −11.65 |

| 350 | −35.1 | −18.9 | −29.5 | −13.3 |

| 400 | −36.75 | −20.55 | −31.15 | −14.95 |

Results are compatible with a 100% C3 diet during the Upper and Middle Miocene, if the precipitation were lesser than 50 mm in the first case and comprised between 50 and 100 mm in the second one. These precipitation estimations agree with sedimentological and palaeontological data.

Studies from Elisabethfeld [19] and Arrisdrift [20] show that, during Early Miocene, the climate was more humid and warmer than it is today. During Middle Miocene, an important climatic change occurred in the southern hemisphere. The installation of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet comes along with important modifications in oceanic circulation patterns [34]. In Namibia, these changes correspond to the development of arid conditions [33], as indicated by the first occurrences of aeolianites during the Namornis oshanai biozone at Awasib. This aridification of the southwestern Africa coastal zone confirms the passage from a warm, humid weather to a drier climate during the Early to Middle Miocene transition.

For the Early Miocene species, the eggshells δ13C values are only compatible with a diet composed of 100% of C3 plants, if the precipitations are lower than 50 mm. This is incompatible with the palaeontological and sedimentological data, which indicate a wetter climate during this period. For precipitations in the range 200–250 mm, the theoretical δ13C (Eq. (4)) is similar to the measured δ13C, only if we admit a large participation of C4 plants in the diet of these birds. This value (about 40%) is undoubtedly too high, but proves a presence of C4 plants in the Early Miocene ecosystem. This development of C4 plants could be related to the weak atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Fig. 2). Previous studies have documented C4 plant occurrences during the Early–Middle Miocene in some peculiar environments. Their presence is recorded in the δ13C of Rhinocerotidae and Proboscidea teeth from the Tugen Hills (Kenya) at 15.3 Ma [15]. The site of Fort Ternan (14 Ma) has also yielded C4 Graminae (Chloridoidae), indicating the existence of open forest ecosystems, with a dominance of grasses [25]. The rarefaction of C4 plants in the ecosystem during Middle and Upper Miocene could reflect an increase in the atmospheric CO2 concentration.

6.2 Late Miocene to Present Namibian climate evolution

The eggshell δ13C increases by 1‰ during the Late Miocene and Pliocene and by 4.5‰ from the Pliocene to the present day (Fig. 2). Despite the ostriches' preference for C3 plants [12], the modern Namibian δ13C eggshell corresponds to a diet comprising only 65% C3 plants (cf. above). In contrast, the δ13C value suggests a greater presence of this plant type in the diet during the Late Miocene. Namib data confirms, therefore, that apart from changes related to regional climatic fluctuations, the Pliocene was a crucial period in the development and ecology of C4 plants in the continental biosphere. It was at this epoch that they became preponderant in some ecosystems [3,15,23,24].

After important fluctuations during the Holocene [14], the Modern (320 ppmv) and Late Miocene (280 ppmv), atmospheric CO2 concentrations are now close together. From Late Miocene to Present, the CO2 concentrations do not seem to be the main control of the C3/C4 plant ratio in the Namibian desert ecosystem. Abundant roots and incipient palaeosoils in Awasib aeolianites show that Upper Miocene was a less arid period than Present. The temperature and rainfall patterns seem to control the increase of the C4 plants in the Namib Desert ecosystem between Late Miocene and today.

7 Conclusions

This preliminary study of Namibian δ13C eggshell has shown changes in the ratite diet from Miocene to Present and has suggested the presence of C4 plants during Early Miocene. The low concentration of the atmospheric CO2 (around 230 ppmv) during this period seems to be the main control parameter of C4 plants occurrence. During the Middle to Late Miocene, regional conditions of temperature and precipitation play an increasingly significant role in the Namibian ecosystem composition.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Geological Survey of Namibia, the Namdeb Diamond Corporation (Pty) Ltd, the National Monuments Council of the Republic of Namibia, the France Embassy in Namibia, the MNHN, the UPMC of Paris, the CNRS (ECLIPSE) and the IFP (France). We thank Nathalie Labourdette for analytical assistance.