Version abrégée

La découverte de microfossiles carbonatés problématiques permet de préciser la stratigraphie des niveaux de base de la couverture sédimentaire paléozoı̈que de San Salvador Patlanoaya (État de Puebla, Mexique) [9,24]. Ce sont des dépôts dont l'âge correspond à l'ancien Tournaisien, c'est-à-dire le Dévonien terminal « Strunien » et le Mississippien basal (Hastarien/Kinderhookien). Ils sont datés par cinq micro-organismes. Le plus fréquent, mais le plus douteux, est proche de la pseudo-algue Petschoria antiqua Berchenko, décrite en lames minces sur des sections incomplètes [2]. Les exemplaires de Patlanoaya (Fig. 3) pourraient aussi se rapprocher d'un groupe de foraminifères (?) assez particuliers, qui a pour représentant principal « Tolypammina » cyclops Gutschick et Treckman [11], à l'inverse, seulement figurés « en dégagé ». Les trois éléments dateurs sont des Moravamminides, autres organismes discutés dont l'acmé se situe au Strunien–Tournaisien : Kettnerammina grandis Chuvashov [6], K. woodi (Berchenko) [2] et Kamaena aff. delicata Antropov sensu Berchenko [2]. Il s'y ajoute de petits foraminifères encroûtants : Tolypammina (?) bransoni Conkin, Conkin et Canis [7]. Dépourvu d'algues véritables et comportant un foraminifère qu'on retrouve dans les dépôts profonds ouest-européens [19], ce peuplement devait se situer sur une rampe externe par une cinquantaine ou une centaine de mètres de fond.

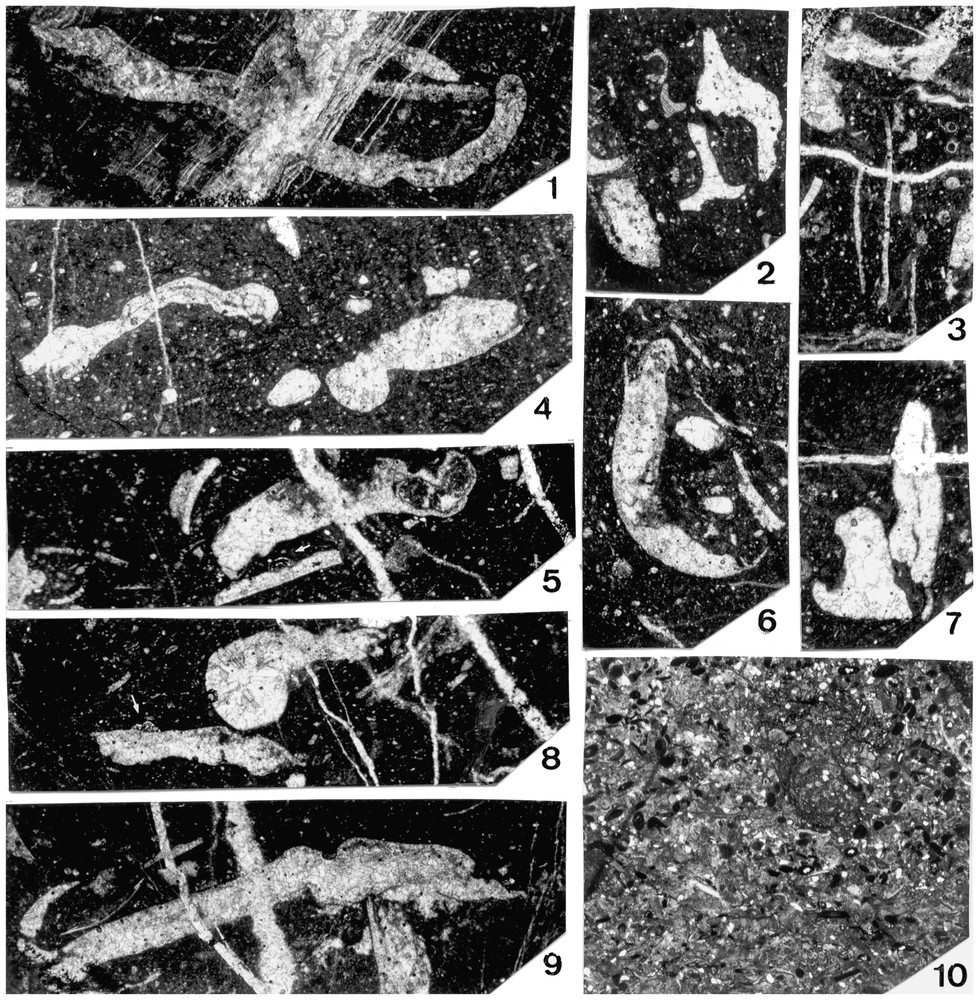

Microfossils (all ×12.5) and microfacies 10 (×7.5) from San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexico). 1–2, 4–9. Petschoria (?) aff. antiqua Berchenko, 1981 [2]. 1. Aspect of algal thallus. 2. Questionable bifurcation. 4. Two specimens looking like ‘Tolypammina’ cyclops Gutschick and Treckman, 1959 (compare with [11, (pl. 36, Figs. 1 and 10)]). 5. A large specimen (top, centre) with an apparent wall (right) passing to a massive sparite (links), and a small fragment (bottom centre; with white arrow), encrusted by Tolypammina (?) bransoni Conkin, Conkin and Canis, 1968 [7]. 6. A Kettnerammina-like section. 7. Characteristic bifurcation and internal microstructure. 8. A ‘tolypamminoid’ specimen (top, centre) (compare with [11, (pl. 36, Figs. 12–14)]) and another one ‘algal’ (bottom) with some whorls of Tolypammina (?) bransoni (white arrow). 9. ‘Algal’ specimen. 3. Kettnerammina grandis (Chuvashov, 1965) [6]. A longitudinal section. 10. Microfacies of marly wackestone with ferruginous oolites.

Microfossiles (×12,5) et microfaciès (×7,5) de San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexique). 1–2, 4–9. Petschoria (?) aff. antiqua Berchenko, 1981 [2]. 1. Aspect de thalle algaire. 2. Bifurcation douteuse. 4. Deux sections apparemment très semblables à « Tolypammina » cyclops Gutschick et Treckman, 1959 (comparer avec [11, (pl. 36, Figs. 1 et 10)]). 5. Un individu assez grand (en haut, au centre), dont la paroi semble s'individualiser à droite, mais passe à une plage de sparite à gauche ; il surmonte un petit fragment encroûté par Tolypammina (?) bransoni Conkin, Conkin et Canis, 1968 [7] (à la pointe de la petite flèche blanche). 6. Une section à allure de Kettnerammina. 7. Bifurcation caractéristique et microstructure interne. 8. Un spécimen « tolypamminoı̈de » (en haut) (comparer avec [11, (pl. 36, Figs. 12–14)]) et un autre d'allure plus « algaire » (en bas), encroûté par un petit Tolypammina (?) bransoni (désigné par la flèche blanche). 9. Spécimen « algaire ». 3. Kettnerammina grandis (Chuvashov, 1965) [6]. Une section longitudinale. 10. Microfaciès de wackestone marneux avec des oolithes ferrugineuses.

Les dépôts de la limite Dévonien–Mississippien n'étaient connus au Mexique que dans les États de Sonora et peut-être de Chihuahua [3,4,21]. Cette rareté a probablement deux explications : (a) les terrains nord-américains et européens se sont tous assemblés et continentalisés, en une sorte d'ébauche de Pangée vers la fin du Dévonien, avec disparition des océans Antler et Iapetus [5,15,16,22,25] ; (b) au sud des États-Unis et au Mexique, les dépôts fini-Dévonien et Tournaisien, qui ont succédé à cette première Pangée, se sont constitués lors d'une phase de rifting, qui a affecté simultanément le bassin de Pedregosa (Nouveau-Mexique, États-Unis) [1], certaines régions du Sonora et du Chihuahua (Mexique) [3,4,10,12,17] et celle de San Salvador Patlanoaya [9,24, cette étude]. Ce rift a dû prendre en écharpe, du nord-ouest vers le sud-est, tous ces sous-bassins, réunis dans un même alignement, ce qui implique qu'à cette époque le terrain Mixteca, de position discutée, jouxtait l'extrémité sud du craton nord-américain et de ses dépendances du Sonora et du Chihuahua. Ce rift, recevant des microfaunes provenant de l'Oural (Russie) et du Donbass (Ukraine), communiquait avec l'océan Rhéı̈que en train de s'ouvrir, parce qu'à cette époque l'océan Antler était déjà suturé [5] et que l'ancienne voie de communication via l'Oural, l'Arctique canadien et l'Alaska [13] était condamnée. Cette communication avec le reste du Rhéı̈que sera encore évidente au Tournaisien supérieur (Osagéen), avec les bioconstructions waulsortiennes semblables à celles de l'Europe occidentale, que nous avons découvertes dans l'État d'Oaxaca [8,24]. Bien que ses séries métamorphiques et sédimentaires paléozoı̈ques soient complexes, le Mexique constitue un domaine favorable aux études géodynamiques, car les océans Iapetus, Antler, Rhéı̈que, Ouachita et Panthalassa y ont fait sentir leurs influences respectives et conjuguées.

1 Introduction

The Late Devonian and Early Mississippian are probably the less known subsystems of the Late Palaeozoic in Mexico. Therefore, we propose in this article two groups of data: (a) the first concerns the microfauna of these ages in San Salvador Patlanoaya; (b) the other one is a reappraisal of the same period in Mexico. Both sets of data allow a palaeogeographic and geodynamic reconstruction of the Mexican plates at the Devonian/Carboniferous boundary, i.e. during the Strunian, an informal and controversial stage or substage, which corresponds moreover for us to the assembly of a first Pangea [22,25], particularly well illustrated in Mexico with the Acatlán Complex.

2 Investigated microfacies and assemblages in San Salvador Patlanoaya

San Salvador Patlanoaya (Fig. 1) is an important section for the Palaeozoic of Mexico [9,23,24,26]. The base of this Formation was first dated as Osagean [26], but this age is in fact Kinderhookian, according to the biostratigraphic criteria of North-American brachiopods Rugauris and Rhytiophora. We discovered, under the Early Mississippian base [sensu 26] of the Patlanoaya Formation, a 100 m-thick sequence (Fig. 2), which was consequently attributed by us to a questionably Late Devonian [9,24]. Lithologically, this sequence is dominated by very fine sandstones with calcareous cements. Fossiliferous beds are very rare. Some wackestones, with ferruginous oolites (Fig. 3, 10), contain questionable fossils. Bioclastic marly wackestones/packstones, rich in ostracods, yield sporadically the studied microfauna/microflora (Fig. 3, 1–9): Petschoria (?) aff. antiqua Berchenko [2], Kettnerammina grandis Chuvashov [6], K. woodi (Berchenko) [2], Kamaena aff. delicata Antropov sensu Berchenko [2], Tolypammina (?) bransoni Conkin, Conkin and Canis [7] (Fig. 3, 5 and 8).

Location sketch map of San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexico).

Carte géologique schématique de San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexique).

Lithological column of San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexico) and location of the fossiliferous beds. Abbreviations: 1 = Strunian smaller foraminifers; 2 = Strunian pseudoalgae; 3 = Kinderhookian brachiopods (e.g., Rhytiophora and Rugauris, see Fig. 4); 4 = Mississippian radiolaria.

Colonne stratigraphique de San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexique) avec l'emplacement des niveaux fossilifères. Abréviations : 1 = foraminifères struniens ; 2 = pseudo-algues struniennes ; 3 = brachiopodes kinderhookiens (ou tournaisiens, en particulier Rhytiophora et Rugauris, mentionnés aussi sur la Fig. 4) ; 4 = radiolaires mississippiens.

This assemblage, which is devoid of dasycladacean algae, corresponds probably to an outer ramp environment (−50 to −200 m deep) similar to that described in the Late Devonian Sonyea Group of New York [18] or in the deep carbonate deposits of Germany [19].

3 Palaeontology and biostratigraphy

Petschoria (?) aff. antiqua [2] is relatively abundant (Fig. 3, 1, 2, 4–9). Generically related to the atypical Petschoria of the Ukrainian Late Tournaisian [2], this taxon differs very much of the true Petschoria of the Late Carboniferous (as illustrated, for example, by [14]). This species is probably new and has a length and a diameter circa three times more than P. antiqua. Although the internal microstructure looks like a recrystallised Petschoria, these microfossils have also some resemblances to the coeval, large ‘Tolypammina’ cyclops Gutschick and Treckman [11].

The other pseudo-algae Moravamminids seem to be more characteristic of the Strunian, and of its equivalents of Ukraine: Ct1a1 and Ct1a2 [2] (Fig. 4): Kettnerammina grandis [6] (Fig. 3, 3), K. woodi [2], Kamaena aff. delicata [2], and are identical to taxa described in Ukraine and Urals [2,6].

Repartition table of the microfossils of San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexico).

Tableau de répartition des microfossiles de San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexique).

A true foraminifer Tolypammina (?) bransoni [7] is characterised by its small size and its attachment type. It is described from the Chouteau Limestone (Late Kinderhookian), but similar forms, attached on conodonts, are known in the Devonian from Europe [19]. The assignment of this foraminifer to the genus Tolypammina remains questionable, due to its wall being apparently silicified and not originally agglutinated.

4 Other Late Devonian/Early Mississippian sequences in Mexico

In Sonora occur several sequences of Late Devonian age, which rest discordantly upon Cambrian or Ordovician deposits. The Murciélagos Formation was already re-dated by us [24] from material of Brunner [3,4], which is of Late Frasnian age, with Proninella ex gr. tamarae Reitlinger, Parathurammina ex gr. paracushmani Reitlinger, Amphipora sp., and of the Famennian with the charophyte Chovanella sp. [3, (pl. 5, figs 1–6)] and the conodont Polygnathus communis Branson and Mehl [4, (p. 84)]. The overlying Represo Formation begins in the Strunian with Laxoendothyra concavocamerata ‘var. 1’ (Conil and Lys) and Laxoendothyra parakosvensis imminuta (Conil and Lys) [24]. Similarly, Mamet [21, (p. 54)] has confirmed in Sonora the Late Frasnian, identified the Famennian with Serrisinella sainsii (Mamet and Roux) and primitive Tournayellidae, and proposed a ‘Late Famennian–Kinderhookian’ age for an assemblage with Paracaligelloides sp., Latiendothyra sp. and Septaglomospiranella sp., which is very probably Strunian in age, because of the abundance of Paracaligelloides in the Strunian parastratotype of the ‘Carrière du Parc’ in France (material B. Mistiaen, unpublished), and in Russia [6].

Other probable Late Devonian Formations summarised in various works [10,12,17] exist in Sonora: Martin Formation and Caliza Cristalina Inferior Formation, and in Chihuahua [17]: lower Monillas, Canutillos and La Percha. All these units must be accurately re-studied, especially the La Percha Formation, apparently very similar in lithology, to the Latest Devonian/Earliest Mississippian member of the San Salvador Patlanoaya Formation (Fig. 2). The deposits attributed to Devonian cherts in Tamaulipas are in fact Pennsylvanian in age and rhyolitic [20].

5 Geodynamic consequences

At the end of the Devonian, many plates collide: Ligerian and Brittany phases in Europe, re-assembly of the central Iapetus [15], the Antler event in western USA [5], and in Mexico there is the assembly of Acatlán Complex [16]. Consequently, a first Pangea may have occurred [22,25]. Nevertheless, an epicontinental seaway remains open in Sonora, especially in the Bisani area (Murciélagos Formation and equivalents [10,12,17]). Concomitantly, the Antler Ocean is probably closing and Rheic Ocean is probably opening.

The Latest Devonian/Earliest Mississippian (i.e., the ‘pre-7 zone’ of [1]) is the beginning of the subsidence of the Pedregosa Basin (New Mexico) [1]. This rifting is also responsible for the opening of the San Salvador Patlanoaya basin. The three basins, Pedregosa, Bisani and Patlanoaya, are possibly linked, due to the occurrence of deposits of the Devonian–Mississippian boundary, absent of the rest of Mexico. These three basins may correspond to a unique rift (Fig. 5). The latter is probably separated of the yet sutured Antler Ocean, but begins its connection with the Rheic. The faunal communications in this case are to the east with the Rheic, extending up to Ukraine, and the Antler does not extend through Alaska and Arctic Canada with the Urals (both ways of communication are theoretically possible). The connection with the eastern Rheic (i.e. western Europa and northern Africa cratons) is evident in the Osagean (late Early Mississippian), as indicated by the identification of Waulsortian mud mounds in Oaxaca [8,24]. The radiolaria-bearing series of San Salvador Patlanoaya (number 5 in Fig. 1) [9,23,24] correspond probably to another phase of the spreading of the Rheic, and to the acquirement of true oceanic environments.

Hypothetical map of Mexico during the Latest Devonian–Earliest Mississippian.

Carte hypothétique du Mexique au passage Dévonien–Mississippien.

6 Conclusions

A Latest Devonian/Earliest Mississippian microfauna discovered in San Salvador Patlanoaya (Puebla, Mexico) contains some microproblematical carbonate micro-organisms and rare encrusting foraminifers: Petschoria (?) aff. antiqua, Kettnerammina grandis, K. woodi, Kamaena aff. delicata and Tolypammina (?) bransoni. This poor assemblage is questionably controlled by two factors: (a) an outer ramp environment in which the foraminifers are rare; (b) the restriction of the seas existing in North America during the Latest Devonian/Earliest Mississippian. The migration of fauna indicates probably a junction between the rift of North America and the opening Rheic Ocean. Many Tournayellids, Endothyrids and Issinellidss migrate during this period: Serrisinella [21], Laxoendothyra [24], Paracaligelloides, Latiendothyra, Septaglomospiranella [21]. No Quasiendothyrids are cited, although they occur in Alaska [13]. This indicates that the migrations along the shelf of the Antler Ocean are impossible during this period.

The Pedregosa Basin, the Bisani Basin (Sonora) and San Salvador Patlanoaya have many stratigraphic similarities. Consequently, the San Salvador Patlanoaya was probably located more to the northwest at this period (Fig. 5).

During the Strunian, the rift Pedregosa/Sonora/San Salvador Patlanoaya constitutes an extremity of the Rheic Ocean. This is probably true until the Late Tournaisian (Osagean), because Waulsortian mud-mounds are well developed in Oaxaca [8,24].

Acknowledgements

This note is a contribution to the programme ‘Ecos-Nord Mexique’ M00U01.