Version française abrégée

0.1 Introduction et cadre géologique

La période Paléocène–Éocène est caractérisée par un réchauffement progressif du globe, après la fluctuation climatique dramatique et relativement brève à la limite du Crétacé/Paléocène, avec des oscillations climatiques régionales humides et arides. Le Paléocène supérieur, en particulier, a été une période critique, pendant laquelle a eu lieu en peu de temps un brusque réchauffement global, le Late Palaeocene Thermal Maximum (LPTM) [41].

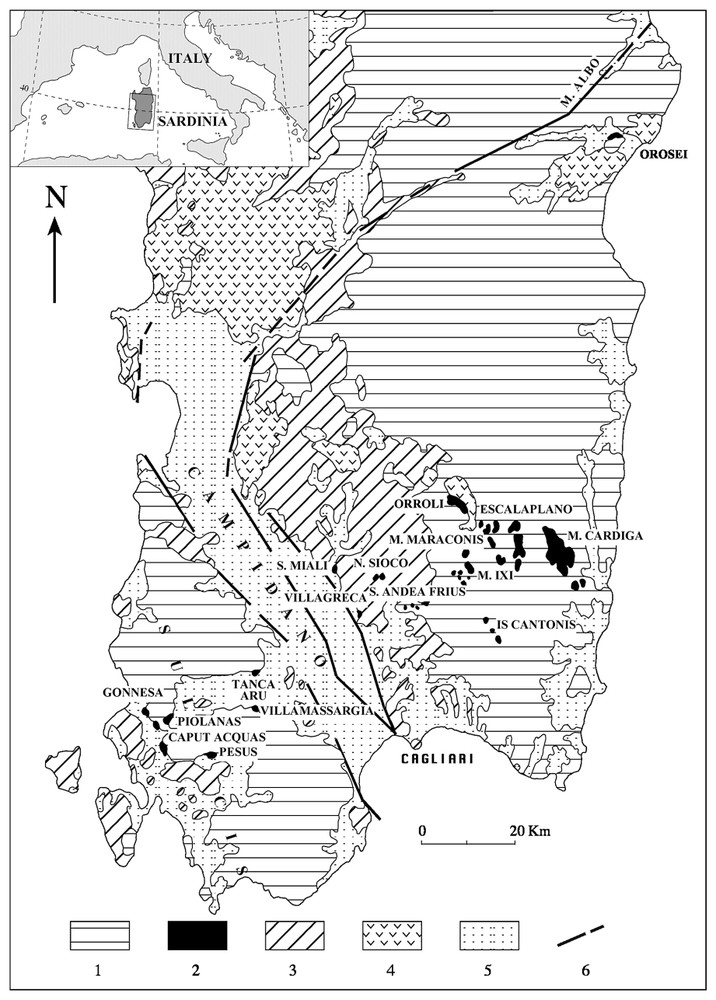

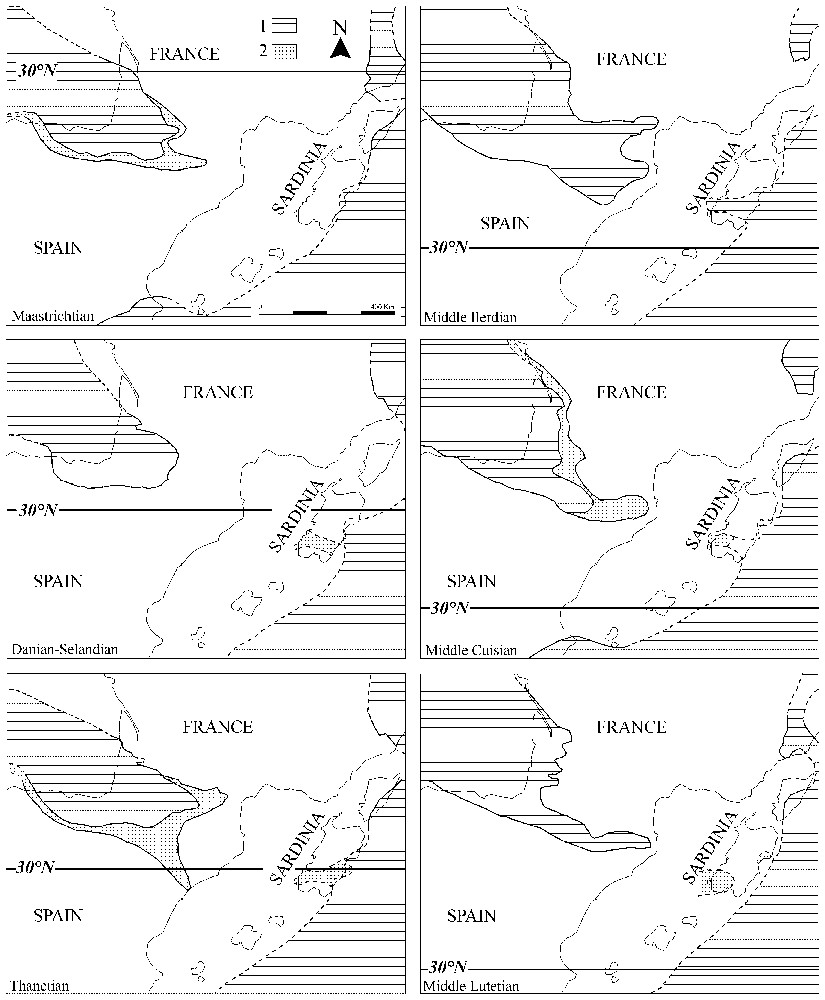

Dans cette étude sont analysées les séquences sédimentaires, continentales et marines, du Paléocène–Éocène moyen de la Sardaigne centro-méridionale (Fig. 1), afin de vérifier la présence d'éventuelles oscillations paléoclimatiques et de les comparer avec celles que présentent des séries de la même époque provenant surtout d'Europe occidentale (péninsule Ibérique et France méridionale), car le bloc sardo-corse (Fig. 2), jusqu'au Burdigalien, faisait partie du bord méridional de la plaque européenne.

Sketch geological map of southern Sardinia: (1) Palaeozoic–Mesozoic basement; (2) Palaeocene-Eocene outcrops; (3) Oligo-Miocene volcanic and sedimentary deposits; (4) Plio-Quaternary basalts; (5) Quaternary sediments; (6) faults.

Carte géologique simplifiée du Sud de la Sardaigne : (1) socle paléozoı̈que-mésozoı̈que ; (2) Paléocène–Éocène ; (3) Dépôts sédimentaires et volcaniques de l'Oligocène–Miocène ; (4) basaltes plio-quaternaires ; (5) sédiments quaternaires; (6) failles.

Generalized palaeogeographic evolution of Sardinia–Corsica, southern France and Spain (after [35], modified): (1) marine sedimentation, (2) continental sedimentation. Palaeolatitude (after [3,39]); the 30°N latitude corresponds to the position of southern Morocco and most Saharan regions today.

Résumé de l'évolution paléogéographique et reconstruction de l'ensemble Sardaigne–Corse, de la France méridionale et de l'Espagne (d'après [35], modifiée) : (1) sédimentation marine, (2) sédimentation continentale. Paléolatitude (d'après [3,39]). La latitude 30°N correspond à la position actuelle du Maroc méridional et de la plus grande partie des régions sahariennes.

0.2 Analyses des affleurements

0.2.1 Paléoaltérites ferrugineuses

Des paléoaltérites ferrugineuses [29,40] sont présentes dans trois affleurements : sur le Monte Maraconis, à Sant'Andrea Frius et à Villamassargia (Fig. 1). Au Monte Maraconis, la composante fine des conglomérats contient de l'hématite, de l'illite, des interstratifiés illite/smectite, de la kaolinite, avec des teneurs en Al de 3,53 % et en Fe de 22,23 %. Dans les lames minces, les caractères pédologiques sont formés exclusivement de marbrures, qui se présentent comme un réseau très dense de revêtements constitués de Fe [6].

À Sant'Andrea Frius, les limons de base rouge-brun contiennent de l'hématite, de l'illite, des traces de kaolinite, avec 6,35 % d'Al et 5,56 % de Fe. Dans les grès rouge clair sommitaux, on trouve de l'hématite et de la kaolinite, de l'illite et interstratifiés illite/smectite, avec des taux de 2,29 % d'Al et de 1,68 % de Fe, tandis que dans les taches de marmorisation rouges prédominent l'hématite et la kaolinite, avec des taux de 1,86 % d'Al et de 4,44 % de Fe %. Les caractères pédologiques sont formés de revêtement d'argile et de Fe sur les grains de quartz et ils occupent les espaces vides, de nodules de Fe, de marbrures.

À Villamassargia, dans les grès silteux, la matrice brun rouge est formée par de l'hématite et de la kaolinite, avec 4,97 % d'Al et 12,73 % de Fe, tandis que les zones sableuses gris clair présentent presque exclusivement de la kaolinite et de l'illite, avec 4,11 % d'Al et 0,24 % de Fe. Les caractères pédologiques sont formés de revêtements d'argile et de Fe sur les grains de quartz et ils occupent les espaces vides.

Actuellement, des altérites présentant des caractéristiques géochimiques (Al=1,36–6,60 % et Fe=0,50–22,20 %) et minéralogiques identiques (prédominance de la kaolinite, smectite subordonnée, abondante gœthite) se forment dans l'état du Maranhão (Nord-Est du Brésil) et sont classés comme des ultisols à plinthites et/ou à ironstones (sols tropicaux ferrugineux dans la classification française) [11,24,25]. En Europe occidentale, des paléoaltérites semblables ont été trouvées uniquement dans les affleurements du Valanginien dans la Meuse, dans l'Est du bassin de Paris [24].

0.2.2 Calcaires à microcodium

Dans la plus grande partie des affleurements, les microcodiums se trouvent dans une « pseudo-brèche » formée par des calcaires micritiques légèrement dolomitisés (5–6 % Mg) parfois à charophytes, ostracodes et gastéropodes pulmonés, probablement d'origine lacustre. Le nom du genre Microcodium Glück est habituellement utilisé dans la littérature géologique, car les processus biologiques relatifs à sa formation n'ont pas encore été éclaircis et le sens du nom formel paléontologique est encore incertain. Pour cette raison, nous écrivons le nom microcodium en minuscule, suivant partiellement les Réfs. [4,13,17]. Les microcodiums se développent comme des revêtements corrosifs de cavités karstiques ou comme une corrosion de sédiments lacustres précédents. Les minéraux argileux sont presque exclusivement constitués d'illite, avec de la kaolinite et un peu de smectite (=montmorillonite). La kaolinite et l'illite sont principalement de type diagénétique. Les affleurements à microcodiums de la France méridionale, qui se situent au Paléocène, sont caractérisés, au contraire, par la présence dominante de la smectite, qui oscille entre 50 et 90 % [4,14,15]. Les niveaux détritiques sardes, avec fragments de microcodium (intra-bioclastes), contiennent aussi une abondante fraction de sable quartzeux (>10 %) à granulométrie variable (60–900 μm), avec des formes principalement anguleuses et plus rarement sub-arrondies. Dans le bassin pyrénéo-provençal [16], ces mêmes niveaux détritiques se trouvent sédimentés, avec une faible quantité d'éléments quartzeux ou argileux. Ceci impliquerait que les aires périphériques étaient protégées par une végétation dense empêchant un apport détritique. En revanche, la présence d'une abondante fraction quartzeuse dans les dépôts sardes pourrait indiquer un dépôt sur des aires proches, ayant une faible couverture végétale [23].

0.2.3 Calcaires à foraminifères ( « Miliolitico »)

Le Sulcis (Fig. 1) possède un ensemble carbonaté qui constitue la succession marine éocène la plus représentative de l'ı̂le. Les premiers sédiments marins sont constitués par des calcaires à macroforaminifères (alvéolines et orbitolitidés), appartenant au Thanétien supérieur–Ilerdien moyen, suivis de calcaires à milioles (faciès « Miliolitico »), appartenant à l'Ilerdien supérieur–Cuisien inférieur [8,30]. Dans les horizons à macroforaminifères, les minéraux argileux sont représentés par l'illite, des interstratifiés illite/smectite et de la kaolinite, tandis que dans ceux à milioles et à rotaliidés sont seulement présentes l'illite et la kaolinite. Ces minéraux, provenant principalement des aires continentales limitrophes, sont essentiellement de type détritique. La palygorskite et la sépiolite, qui sont présentes (30 à 60 %) en Espagne méridionale [20], manquent.

Dans les calcaires à alvéolines et à orbitolitidés, on remarque la présence de grains de quartz, avec des surfaces de fracturation de type éolien, en pourcentages souvent supérieurs à 10 %. La granulométrie indiquerait, plutôt qu'une sélection par des courants, une provenance des zones côtières adjacentes possédant une végétation rare.

0.2.4 Dépôt à charbon ( « Produttivo »)

Dans le Sulcis, les calcaires du « Miliolitico » sont recouverts d'une séquence formée de marnes, argiles et calcaires principalement dulçaquicoles, à ostracodes et à charophytes. On trouve, intercalés dans ces niveaux, sur une épaisseur de 15 à 30 m (faciès « Produttivo »), des bancs de charbon attribués au Cuisien sur la base des associations microfloristiques. Les essences les plus courantes étaient les palmiers, Myricaceae et des fougères tropicales. Dans les derniers niveaux charbonneux, l'association des pollens indique un Lutétien inférieur [33,36]. Dans les niveaux carbonatés, l'étude des minéraux argileux, principalement détritiques, mais localement diagénétiques, a montré la présence prédominante de kaolinite.

0.3 Conclusion

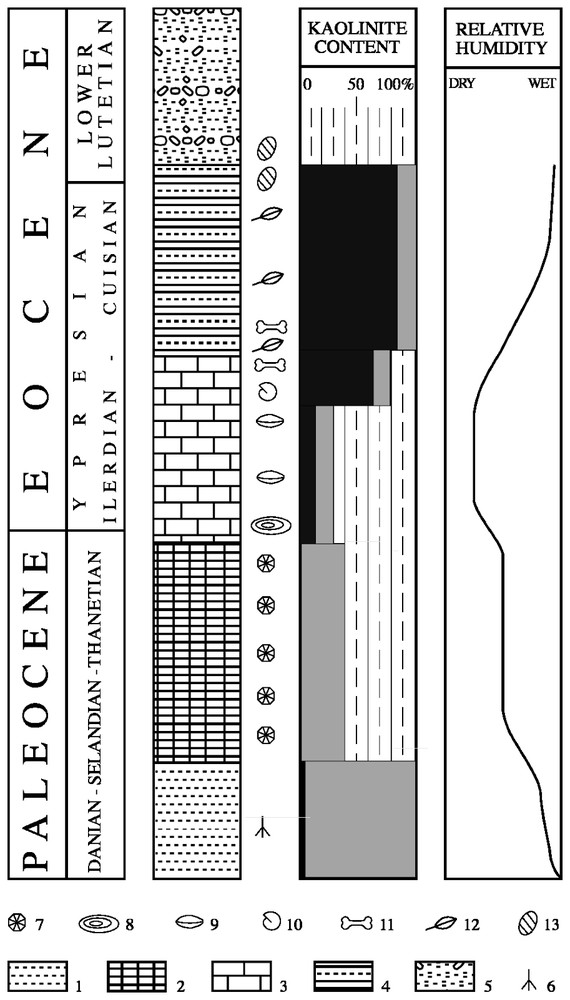

L'évolution climatique que l'on déduit des analyses des différents apports détritiques provenant de l'arrière-pays est interprétée comme suit (Fig. 3) :

- (1) les paléoaltérites ferrugineuses du Paléocène, avec une forte teneur en Al et en Fe, peuvent être comparées à celles qui se forment actuellement dans le Nord-Est du Brésil et celle qui ont été découvertes dans les affleurements du Valanginien dans la Meuse (Est du bassin de Paris) et qui indiqueraient une altération dans un contexte climatique tropical subhumide ;

- (2) les sédiments continentaux détritiques à microcodiums, avec une faible teneur en kaolinite, sont caractérisés par une abondante fraction quartzeuse, qui impliquerait la présence d'une végétation rare qui ne protégeait pas les sédiments clastiques des aires émergées de l'érosion ; ceci pourrait signifier que les fragments de microcodiums se sont déposés dans un contexte climatique semi-aride ;

- (3) les calcaires à macroforaminifères, avec une fraction quartzeuse caractérisée par de surfaces de fracturation de type éolien, une faible teneur en kaolinite et de fortes concentrations de miliolidés, suggèrent un apport sédimentaire des aires littorales couvertes d'une végétation rare durant une phase climatique semi-aride ; l'absence de palygorskite et de sépiolite (indicateurs de climats arides), présents en Espagne méridionale, indiquerait une plus grande aridité dans cette région, qui était assez proche de la Sardaigne ; le remplacement des milioles par les rotaliidés dans la portion sommitale du « Miliolitico » et la présence d'une forte teneur en kaolinite indiqueraient une augmentation de la pluviosité dans l'arrière-pays où était aussi présent un périssodactyle, semblable aux tapirs, qui vivent actuellement dans les forêts humides ;

- (4) dans les niveaux carbonatés du gisement à charbon du « Produttivo », l'absence de quartz indiquerait la présence d'une végétation dense le long des rives du bassin lacustre ; les indications données par l'association pollinique (principalement des palmiers et des fougères tropicales) et la présence d'une importante quantité de kaolinite, indiqueraient une évolution sous un climat tropical humide à subhumide.

Kaolinite content (maximum=grey, minimum=black) and climatic humidity excursions suggested for the southern Sardinia palaeogenic deposits: (1) ferruginous palaeoalterites (ironstones); (2) microcodium units; (3) foraminiferal limestones (‘Miliolitico’); (4) coal series (‘Produttivo’); (5) continental Cixerri Formation; (6) palaeosols; (7) microcodium; (8) alveolinids; (9) miliolids; (10) Rotaliids; (11) vertebrates; (12) pollens and plant debris; (13) charophytes (lithological column not to scale).

Teneur en kaolinite (gris=maximum, noir=minimum) et variations de l'humidité climatique proposées pour les dépôts paléogènes du Sud de la Sardaigne : (1) paléoaltérites ferrugineuses ; (2) niveaux à microcodium ; (3) calcaires à foraminifères (« Miliolitico ») ; (4) dépôts à charbon (« Produttivo ») ; (5) formation continentale du Cixerri ; (6) paléosols ; (7) microcodium ; (8) alvéolines ; (9) milioles ; (10) rotaliidés ; (11) restes de vertébrés ; (12) pollens et débris de végétaux ; (13) charophytes (colonne lithologique sans échelle). Masquer

Teneur en kaolinite (gris=maximum, noir=minimum) et variations de l'humidité climatique proposées pour les dépôts paléogènes du Sud de la Sardaigne : (1) paléoaltérites ferrugineuses ; (2) niveaux à microcodium ; (3) calcaires à foraminifères (« Miliolitico ») ; (4) dépôts ... Lire la suite

1 Introduction

There is a consensus in considering that the Palaeocene–Eocene times were characterized at mid-latitudes by progressive global warming, following the dramatic and relatively short-term perturbation in climate at the Cretaceous–Palaeocene boundary, with regional climatic fluctuations from a humid to an arid regime. In particular, the abrupt global warming of the Latest Palaeocene was a critical time in earth history, the ‘Late Palaeocene Thermal Maximum’ (LPTM) [41].

The sedimentary sequences of the Palaeocene–Middle Eocene of central–southern Sardinia (Fig. 1) have been examined with the intention of ascertaining the local influence of palaeoclimatic oscillations. They are then compared with coeval series from western Europe (Iberian Peninsula and southern France) because, until to the Burdigalian, the Sardinia–Corsica block (Fig. 2) formed an integral part of the southern margin of the European plate.

2 Palaeoclimatic background

During the Early Palaeocene, the subtropical climate of western Europe varied from temperate, up to the palaeolatitudes of N43°, to tropical as far as and including southern Spain [2]. These climatic zones shifted southwards by 5–10° during the Middle–Late Palaeocene, indicating a general warming of western Europe. The presence in the Palaeocene–Early Eocene of the tropical Nypa palm in the Anglo-Franco-Belgian Basin testifies to a warmer climate. However, the abundant rainfall and its periodicity may have been the most important factor underlying local differences in western European regions [35]. Examples of local increasing aridity during Palaeocene–Lower Eocene transition have been documented in southern Spain [20,37]. Furthermore, the pollen and floristic assemblages identified in northeastern Spain in the Latest Cretaceous–Early Eocene are testimonies to an initially unstable tropical climate (Maastrichtian–Danian), with a slow temperature and/or humidity decrease. Then, in the Late Palaeocene, the climate became rainier, cool temperate and oceanic, finally changing gradually to tropical in the Early Ilerdian (=Early Eocene), with a progressive increase in temperature and aridity [23].

3 Regional setting

In NW Sardinia, the Cretaceous marine sedimentation ended in the Santonian–Campanian [9]. In eastern Sardinia, on the other hand, a marine ingression is documented by some deposits of Early Maastrichtian, while the Late Maastrichtian is represented by rudists and larger foraminifers recorded as clasts within Tertiary conglomerates [10]. Palaeocene continental sedimentation is documented in southern Sardinia (Fig. 1), with ironstones [29] followed by microcodium carbonates in numerous outcrops [22].

During the Early Ypresian (=Ilerdian), an extensive and well-documented marine ingression flooded the central-southern Sardinia, persisting up to the Late Ypresian (=Cuisian) in some areas such as central-eastern Sardinia [8,30]. In the Southwest of the island (Sulcis), the main sequence includes basal limestones, containing alveolinids and orbitolinids, followed by the miliolid unit (the ‘Miliolitico’ facies). However, it is only in southwestern Sardinia that this prevalently carbonate sequence is overlain by a succession of marly limestones, marls, limestones and clays containing freshwater ostracods and charophytes. Interbedded are coal layers that are still mined (the ‘Produttivo’) of Late Ypresian (=Cuisian)–Early Lutetian age, on the basis of the microflora assemblage [8,28,33]. Finally, the succession is interrupted by the molassic deposits of the Cixerri Formation, Early Lutetian–Oligocene (?) in age [1,32].

4 Methods

Palaeontological, petrographical, mineralogical and geochemical data have been compared in order to gain a deeper insight into the sedimentary environments and palaeoclimates of central-southern Sardinia during the Palaeocene–Early Eocene times. Clay minerals (fraction <2 μm) from the clay deposits and the insoluble residues of carbonate rocks were analysed using Moore and Reynolds' methods [26]. X-ray powder diffraction data of clay minerals were collected using an automated Philips PW1710 diffractometer with graphite-monochromatized Cu Kα1 radiation (

5 Analysis of the outcrops

5.1 Ferruginous palaeoalterites

The ferruginous palaeoalterites [29,40] present at the base of three outcrops are composed of conglomerates at Monte Maraconis, clayey siltstones and coarse sandstones at Sant'Andrea Frius and silty sandstones at Villamassargia (Fig. 1). The detrital components come from the erosion of Palaeozoic igneous and metamorphic rocks and subordinately from Mesozoic siliciclastic and carbonate sediments and their subaerial weathering. At Monte Maraconis, the conglomerates (0.2–5 cm, 70% clasts) are mainly lithic with unsorted, angular, embayed quartz pebbles and subordinate metasandstone clasts in a reddish-brown (10R4/4 Munsell) clay matrix. They include small lenses, consisting in slightly cemented medium-size light grey quartzose sandstones (5Y6/1) containing around 5% small lithic gravels. No sedimentary structure has been recognised. Their thickness is 0.60 m. The matrix contains hematite and clay minerals: illite (39%), illite/smectite mixed layers (24%) and kaolinite (37%) with 3.53% Al and 22.23% Fe. The sandstones contain: illite (57%), illite/smectite mixed layers (16%), kaolinite (27%); 7.58% Al and 2.00% Fe. The pedofeatures, on thin sections, are represented exclusively by macroscopic mottles, which appear as a very dense network of Fe sesquioxidic coatings [6].

At Sant'Andrea Frius, unfossiliferous, reddish–brown (10R5/2) slightly cemented quartzose clayey siltstones occur in the basal deposits; the reddish siltstones exhibit distinct grey mottling (5Y6/2), and contain quartz grains and 2–5% of metasandstone scattered grains. No sedimentary structures have been recognised; thickness 10 m. The siltstones are overlain by coarse, sandy siltstones slightly cemented, quartzose, light red (7.5Y6/8) with red mottles (2.5YR4) and traces of plane-parallel lamination in a sandy-clay matrix; the contact surface with the underlying lithology is erosional; the thickness is 3 m. In the lower part of the sandstones, a discontinuous layer of light red microconglomerates occurs, up to 30 cm thick and composed of quartz and subordinate sandstone clasts. The reddish-brown clayey siltstones contain hematite and illite (96%), with traces of kaolinite (4%), 6.35% Al and 5.56% Fe. The light red sandstones contain hematite and kaolinite (41%), illite (48%) and illite/smectite mixed layers (11%), with 2.29% Al and 1.68% Fe, while in the red mottles hematite and kaolinite (100%) dominate, with 1.86% Al and 4.44% Fe. The pedofeatures are represented by compound coatings of clay and Fe around quartz grains and voids, nodules of Fe, mottles and coatings of Fe surrounding pores and grains.

At Villamassargia, fine, light grey (5YR8/1), silty quartzose lithic sandstones (4 m) occur with millimetre size quartz clasts and scattered reddish brown (10R3/4) iron nodules. Average size of nodules is 10–20 cm (50%); no sedimentary structures have been recognised. The reddish–brown matrix is composed of hematite and kaolinite (100%), with Al and Fe contents of 4.97% and 12.73%, respectively. The light grey zones are composed almost entirely of kaolinite (98%) and illite (2%) with 4.11% Al and 0.24% Fe. The pedofeatures are represented by compound coatings of clay and Fe around quartz grains and voids. SEM study of the clay minerals reveals a crystalline aspect with the typical booklet structure of diagenetic origin.

All these sediments were deposited in an alluvial environment that has been interpreted as a flood plain (Sant'Andrea Frius and Villamassargia) with channels (Sant'Andrea Frius), whereas the sediments at Monte Maraconis have been interpreted as debris-flow deposits. The contents of Al and Fe are compared with contents of continental alterites formed in the state of Maranhão, northeastern Brazil, %Al ranging between 1.30 and 6.60; %Fe between 0.50 and 26.90, abundant kaolinite, small smectite, abundant goethite, which are classified as ultisols containing plinthite and/or ironstones [11]. Such modern soils (Ferruginous Tropical Soils in the French classification [24]) form in a subhumid tropical climate, with a mean temperature of 26 °C and maximum annual rainfall of 1800 mm. In the West Europe, palaeosols with plinthites have been found only in the Valanginian beds in the Meuse region (East of the Paris Basin), pointing out probable high-temperature climate, with an alternation of humid and dry conditions [24,25].

5.2 Microcodium limestones

These limestones [22,28] have been recognised chiefly in central-southern Sardinia (Fig. 1). The genus name Microcodium Glück is commonly used in the geological literature; nevertheless, as the biological processes underlying its formation have not yet been fully clarified, the significance of the palaeontological formal name is still uncertain. For these reasons, we use microcodium, written in lower case, partly following references [4,13,17]. Clasts of shallow-water marine limestones, of Danian–Montian age [10], were found inside the post-Cuisian conglomerate of Cuccuru'e Flores–Orosei (northeastern Sardinia). Microcodium ‘incrustations’ in these clasts and their absence in clasts of marine limestones referred to the Thanetian-Middle Ilerdian coexisting in the same conglomerate suggest a continental period, which occurred between the Early and Late Palaeocene [10].

In other outcrops of southern Sardinia, the microcodium unit overlies a Palaeozoic or Mesozoic carbonate substratum, being covered by marine deposits with Ilerdian foraminifera, whereas the first microcodium horizons of Sant'Andrea Frius appear in Thanetian dated by charophytes (unpublished).

At Caput Acquas (Fig. 1), the microcodium layer is overlain by a marine transgressive Eocene conglomerate and at Gonnesa and Piolanas by the limestones of the ‘Miliolitico’ of Late Thanetian (?)–llerdian age. Only at Villamassargia are the microcodium deposits directly overlain by the Middle Eocene continental deposits of the Cixerri Formation, with charophytes indicating a basal Lutetian [1].

In the majority of outcrops, microcodium occurs within a ‘pseudo-breccia’ that consists of probably lacustrine, slightly dolomitised (5–6% Mg) micritic limestones containing occasional and scattered charophytes, freshwater ostracods and pulmonate gastropods. Microcodium developed as layered encrustations of pseudo-karstic cavities or by corrosion of previous lacustrine deposits.

The clay minerals of the microcodium beds are composed almost entirely of illite (89–26%), subordinate kaolinite (40–0%) and minor smectite (=montmorillonite) (13–0%). Kaolinite and illite are mainly diagenetic. Conversely, the microcodium limestone outcrops of same age [4,14,15] in southern France contain dominant smectites (50–90%).

The Sardinian microcodium debris (intra-bioclasts) always contain an abundant quartz fraction (>10%) with dominant angular and subordinate sub-rounded grains of variable size (60–900 μm). SEM revealed deep dissolution grooves, due to a previous intense pedogenetic activity and a thick coating of secondary silica. Furthermore, absence of abrasion in the coating suggests a limited transport, probably by ephemeral streams. In the Pyrenees–Provençal Basin, microcodium debris (products of mechanical disintegration of microcodium colonies that were localized initially around the emerged and eroded lake peripheries) is locally abundant in sediment characterized by little amounts of quartz or clay detritus [16]; it implies lateral protection from river supply, probably due to the presence of a filter formed by dense reed vegetation. The occurrence of an abundant quartz fraction in the Sardinian debris might indicate an environment with a sparse vegetation cover, possibly corresponding [7] to a present-day scrubland vegetation (low Mediterranean shrub association interspersed with numerous unvegetated areas) that formed below a semi-arid Mediterranean climate.

5.3 Foraminiferal limestones (‘Miliolitico’)

In the Sulcis region exists a carbonate complex (50–60 m thick), which is the most developed unit of the Eocene marine sequence of Sardinia (Figs. 1 and 2). The first marine sediments are represented by limestones with larger foraminiferal assemblages (alveolinids and orbitolitids) referred to the Late Thanetian–Middle Ilerdian owing to the occurrence of Alveolina (Glomalveolina) cf. primaeva Reichel and of Alveolina cucumiformis Hottinger. These sediments are overlain by limestones with an oligotypical miliolid fauna (‘Miliolitico’) referred to the Late Ilerdian–Early Cuisian [8,30]. The alveolines are gradually replaced upwards by orbitolitids whose modern counterpart Marginopora lives in a protected environment; these limestones were deposited in a shallow coastal basin [21]. Also in the Ilerdian of northern Corbières (France), this foraminiferal assemblage is considered typical of a protected shelf [31]. The dominant miliolids and small trochospiral rotaliids occurring in the upper part of the ‘Miliolitico’, along with the absence of textulariids, suggest a protected lagoonal environment with very shallow depth. Similar faunistic relationships are to be observed in the Ilerdian of Corbières [31] and today in the Burgao Bay in southern Somalia [21], which has a dry tropical climate, sparse vegetation along the shores and maximum annual rainfall of 400 mm. Upwards in the carbonate succession, the dominant miliolids are replaced almost completely by small rotaliids. This also suggests restricted environments with greater freshwater inflow and terrigenous input, similar to those today found in the Aratu Bay at Bahia, in Brazil [21], characterised by a rainy tropical climate and maximum annual rainfall of 1100 mm. The occurrence near the top part of the ‘Miliolitico’ of limestone beds with abundant small rotaliids alternating with miliolid beds would thus indicate an instable period characterised by increased rainfalls. This alternation may well prelude the onset of the subsequent hot and humid climate (‘Produttivo’).

In the alveolinid and orbitolitid limestone unit, angular to rounded monocrystalline quartz grains often exceed 10%, with a size distribution (50–800 μm, up to 1700 μm) poor sorted, excluding current transport. SEM analysis shows that the clasts are coated with a recrystallized silica patina of diagenetic nature, which also covers the carbonate shells. However, where the patina is discontinuous, it is possible to demonstrate that the original surface bears oriented etching pits and dissolution grooves, suggesting a previous corrosion in a pedogenetic environment. Conchoid fracture surfaces locally visible on the larger grains and poorly affected by dissolution, indicate grain rejuvenation. In the modern deposits, such features are observed in beach dune sediments, characterized by high-energy wind conditions. The fossil Orbitolites are usually found in carbonate facies devoid of terrigenous input [18]; the Sardinian association of limestone and quartz grains, characterized by conchoid fracture surfaces, with Orbitolites therefore suggests aeolian transport from sparsely vegetated littoral areas.

Concerning isotopes, δ 13C values range from −1.87 to −3.30 and δ 18O from −5.10 to −7.01; these depleted values with respect to standard values of Lower Eocene marine limestones [38] may be interpreted as a diagenetic modifications [12] and therefore will not be used for a palaeoclimatic reconstruction.

In the Ilerdian limestones containing larger foraminifers, clay minerals are represented by illite (54–76%), illite/smectite mixed-layers (7–9%) and kaolinite (14–30%). Palygorskite and sepiolite (markers of arid conditions), present (30–60%) in southeastern Spain, are lacking [20]. Miliolid and small rotaliid limestones contain illite (21–36%) and kaolinite (64–79%). They are mainly detrital.

At Nuraghe Sioco, the Cuisian beds differ by Ilerdian ones for a lower miliolid/larger foraminifer ratio, while the quartz fraction is nearly absent and the clay minerals are dominated by illite (5–86%), with illite/smectite mixed layers (3–8%) and detrital kaolinite (10–46%).

At the top of the ‘Miliolitico’, in a bed rich in small rotaliids, a half lower jaw of Atalonodon monterinii Dal Piaz, a perissodactyl similar to the modern tapirs, has been discovered [21]. The shape of the upper molars suggests a dominant tendency to nibble marsh plants.

5.4 Coal deposits (‘Produttivo’)

The carbonate unit of ‘Miliolitico’ is overlain, in the Sulcis region, by a sequence of marly limestones, marls, limestones and clays with freshwater ostracods and charophytes. Within these strata are intercalated several coal beds 15–30 m thick (‘Produttivo’). A Cuisian age has been assigned to the lower–middle part of this succession on the basis of the microflora assemblages observed in the lowermost coal beds. The most common plants are palms, Myricaceae, tropical ferns. In the uppermost coal unit, the pollen assemblage suggests an Early Lutetian age [33,36].

The analysis of deep cores from the Sulcis area revealed intercalations of pure lacustrine carbonates with charophytes, ostracods and freshwater gastropods in the ‘Produttivo’ [12]; the absence of in situ evaporites, the limited extent of pseudomicrokarst and desiccation cracks and the fact that the depositional sequences are capped by palustrine coal seams point to subhumid climatic conditions with strong seasonal variations. Furthermore, the limestones are completely devoid of quartz grains, suggesting dense vegetation along the shores of the lacustrine basin. Analysis in the carbonate sediments of the clay minerals, mainly detrital but locally diagenetic (SEM observations), indicate the presence of illite (15–0%) and kaolinite (85–100%).

The Florida Everglades [12,19,34] may be the modern counterpart of the ‘Produttivo’ in terms of both sedimentary environment and tropical–subtropical climate.

Two jaw pieces belonging to another perissodactyl similar to modern tapirs, Lophiodon sardus (=Paralophiodon sardus) Bosco, have been discovered [21] at the base of the ‘Lignitifero’. The complete modification of the upper molars and the large hypoconulid cutting action rather than a crushing action, which suggests a feeding adaptation to the forest environment. Such a lophiodont adapted to hot-humid climates agrees with the teeth of Amphiperatherium sp., a large marsupial of tropical climates found in the ‘Lignitifero’ [21].

6 Discussion and conclusions

The kaolinite content authigenesis depends first upon rainfall. As a matter of fact, high kaolinite abundance is assumed to be indicative of warm, humid climates on well-drained continental areas, because high precipitation accelerates leaching of parent rocks. The analysis of the contents shows that, from the oldest to the youngest deposits: (A) the palaeosoils with ironstones contain up to 100% diagenetic kaolinite; (B) the microcodium debris contain only less than 40% diagenetic kaolinite; (C) the foraminiferal limestones also contain less than 30% detrital kaolinite in the lower strata with larger foraminifers, while the ratio increases up to 79% in limestones rich in miliolids and small rotaliids; (D) the carbonate sediments in the coal deposits contain up to 100% detrital kaolinite.

The quartz grains observed in the detrital sediments containing microcodium and in the foraminiferal limestones, especially in the strata containing larger foraminifers and miliolids, suggest that the surrounding continental sedimentary environments were not densely vegetated.

Today's larger foraminifers are found in shallow marine environments with mean annual temperature over 22–23 °C and optimum temperature around 25 °C. A larger foraminifer assemblage is thus indicative of shallow warm water [27]. The Sardinian Palaeogenic successions (‘Miliolitico’) contain Alveolina and Orbitolites, two larger foraminifer genera always associated with miliolids, on average in percentages of over 50%. The same proportions of miliolids and similar larger foraminifers are today found in the subtropical environments of the Red Sea and the Arabian Gulf, while in Provence they do not exceed 35% [27]. The dominant miliolid assemblages more precisely indicate a high-salinity environment, suggesting a dry tropical climate. The appearance and increase of small rotaliid foraminifera at the top of the ‘Miliolitico’ rather suggest a transition towards a more humid, tropical climate. The mammal remains discovered in the upper part of the Ilerdian sequence are similar to modern tapirs living in humid forests.

The pollens associations of coal layers also indicate an hygrophilic vegetation composed chiefly of tropical palms, Myricaceae and ferns in accordance with a humid tropical climate.

In conclusion, the climatic trend deduced from the analyses of detrital components originating in adjacent continental areas during the Palaeocene–Middle Eocene times may be as follows (Fig. 3):

- (1) Palaeocene ironstone palaeosoils, compared with those forming in northeastern Brazil and Valanginian ones in the Meuse region (East of the Paris Basin) indicate alteration within a climatic context, like subhumid tropical climate;

- (2) the continental debris, poor in kaolinite-containing microcodium, are characterised by an abundant quartz fraction; it could imply a reduction in vegetation cover that protects clastic sediments from physical erosion by winds and also water; this suggests that microcodium debris were deposited probably in an environment with semiarid climatic conditions (Mediterranean climate);

- (3) the large foraminiferal limestones contain quartz grains, characterized by aeolian conchoid fracture surfaces and low detrital-kaolinite, high illite, illite/smectite mixed-layer contents, suggesting sediment source from sparsely vegetated adjacent semiarid littoral areas; palygorskite and sepiolite are lacking; their presence in southern Spain, which was very near to Sardinia, evidences more arid conditions; the appearance in the top of the ‘Miliolitico’ of intercalated layers with abundant small rotaliid foraminifers associated with a higher detrital-kaolinite content, suggests an increase of rainfall in the surrounding areas, where is present a perissodactyl similar to the modern tapirs living in humid forests;

- (4) in the carbonate sediments of the ‘Produttivo’ unit, the absence of quartz suggests dense vegetation along the shores of the lacustrine basin; the pollen assemblages in the coal layers, palms, Myricaceae and tropical ferns and dominating detrital kaolinite, confirm the evolution towards a humid–subhumid tropical climate.

Acknowledgements

This study was carried out with the financial support of the Italian Ministry for Universities and Scientific Research and Technology. The authors are grateful to R. Matteucci, J. Pignatti and J.-C. Plaziat for the critical review of the text and to S. Mameli and R. Sinzula for their technical assistance.