Version française abrégée

Le golfe de Corinthe est une région où l'extension crustale présente des taux élevés de l'ordre de 10–15 mm a−1 durant le siècle dernier [4,5]. La séquence de séismes de 1981 et le séisme d'Aigion de 1995 sont les plus récents événements ayant causé des dégâts majeurs (Fig. 1).

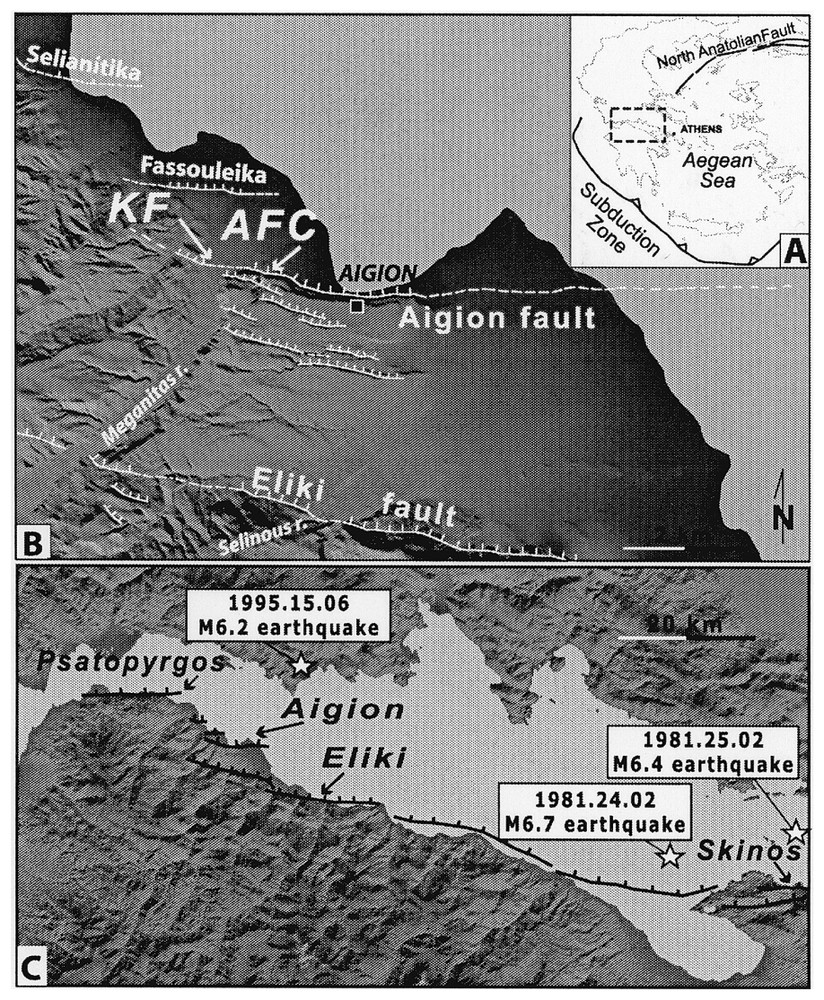

(A) Location of the Gulf of Corinth (dashed rectangle) in Central Greece. (B) Map of the Aigion Fault, dashed when uncertain. Ticks indicate down dip fault direction. Arrows point to the studied sites: AFC and KF. (C) Major normal faults along the southern shore of the Corinth Gulf. Star indicates the 1995 mainshock [2] and the two first 1981 shocks [9].

(A) Position du golfe de Corinthe (dans le rectangle) en Grèce centrale. (B) Trace de la faille d'Aigion, en tireté quand elle est incertaine. Les barbules indiquent le côté affaissé. Les flèches indiquent les sites étudiés : AFC et KF. (C) Failles majeures le long de la bordure sud du golfe. Les étoiles représentent les épicentres des séismes de 1995 [2] et des deux séismes de 1981 [9].

Malheureusement, les informations sur les séismes historiques sont peu nombreuses et l'association d'une faille individuelle avec un séisme a été possible seulement pour les failles d'Eliki et Skinos. Finalement, il y a un fort besoin de caractérisation des failles sismogéniques dans le but de comprendre les mécanismes sismogènes qui existent dans le golfe de Corinthe, afin de faire reposer le risque sismique sur des observations solides. Dans cet article, nous tentons de comprendre le comportement sismique de la faille d'Aigion à travers des investigations paléosismologiques.

La faille d'Aigion est une des failles normales bordant le Sud du golfe, considérées comme les structures majeures responsables de la sismicité de celui-ci. Les séismes de 1748 et 1888 [12] qui ont affecté la région d'Aigion peuvent être associés à la faille d'Aigion, mais cela doit être vérifié. En 1995, un séisme de magnitude 6,2 s'est produit à 15 km au NNE d'Aigion, sur une faille normale à très faible pendage. Les données sismologiques, GPS et SAR montrent que le séisme n'est pas localisé sur la faille d'Aigion, mais qu'il est à l'origine de petites ruptures cosismiques le long du tracé de la faille [2,10]. La faille d'Aigion a une expression morphologique majeure dans sa partie centrale, avec un escarpement abrupt de 150 m (Fig. 1). Les replats, appartenant au stade marin isotopique 5e au sommet de l'escarpement soulevé par la surrection au mur de la faille, suggèrent un taux de surrection de 1,2 mm a−1 [8]. Vers l'est et l'ouest, la faille pénètre dans les sédiments récents ; elle est affectée par des processus sédimentaires alluviaux et elle a par conséquent une expression bien plus faible. Une extension orientale possible offshore de 3 km a été mise en évidence par des études sonar [16]. À l'ouest, les escarpements des failles de Fassouleika et Selianitika peuvent représenter des extensions obliques de la faille d'Aigion. Sur la base de ces observations, la longueur minimum de la faille d'Aigion serait de 14 km.

Afin de dater des paléoséismes sur la faille d'Aigion et d'estimer des taux de déplacement, la présente étude a été menée sur une tranchée, une carotte et un affleurement artificiel localisés sur le tracé de la faille.

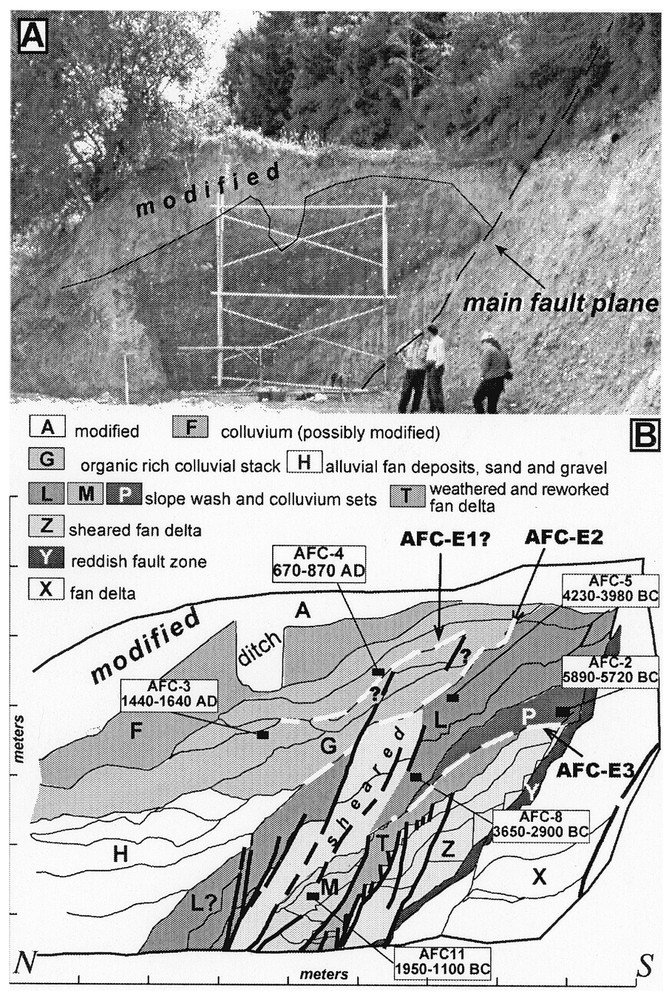

L'affleurement artificiel (AFC), près de la ville d'Aigion (Fig. 1) présente 4 m de colluvions déposées contre le plan de faille majeur (Fig. 2). Le mur de la faille est composé de sables et de graviers d'un fan delta typique. La zone de faille fait 5 m de large et s'exprime par une déformation en escalier de tous les sédiments. Sur la base de l'analyse des dépôts et des structures dans l'affleurement, nous suggérons l'existence d'au moins trois événements, avec des rejets individuels de 0,6 à 1 m durant les derniers 8000 ans (Fig. 2). L'âge de l'événement le plus récent (AFC-E1) reste douteux, à cause des incertitudes sur les âges des échantillons. Il peut être survenu juste avant 670–870 AD ou très près de 1440–1640 AD. Du fait de l'absence de la partie supérieure de l'affleurement, il n'est pas possible de retrouver les traces des ruptures de surface les plus récentes de la faille d'Aigion, comme celles du séisme de 1995. Plusieurs taux de déplacement vertical ont été définis, en considérant différentes corrélations et en prenant en compte les diverses datations réalisées. Ils sont compris entre 0,3 et 4,1 mm a−1.

(A) Photo of AFC site. The fault forms the contact between fan-delta deposits in the footwall and colluvium on the hangingwall. (B) Simplified log of the exposure from a 1:20 scale survey. Black boxes show location of radiocarbon-dated samples, ages are dendro-chronologically corrected [13]. White dashed lines indicate the event horizons (i.e., the ground surface at the time of an earthquake): AFC-E1, AFC-E2 and AFC-E3.

(A) Photo du site AFC. La faille principale met en contact les dépôts de fan-delta du mur de la faille et les colluvions du toit de la faille. (B) Log simplifié de la coupe (levée au 1:20). Les rectangles indiquent la position des échantillons pour les datations 14C ; les âges 14C sont indiqués avec l'intervalle , corrigé d'après les données dendrochronologiques [13]. Les lignes en tiretés blancs indiquent les horizons repères (c'est-à-dire la surface topographique lors des événements sismiques) : AFC-E1, AFC-E2, AFC-E3.

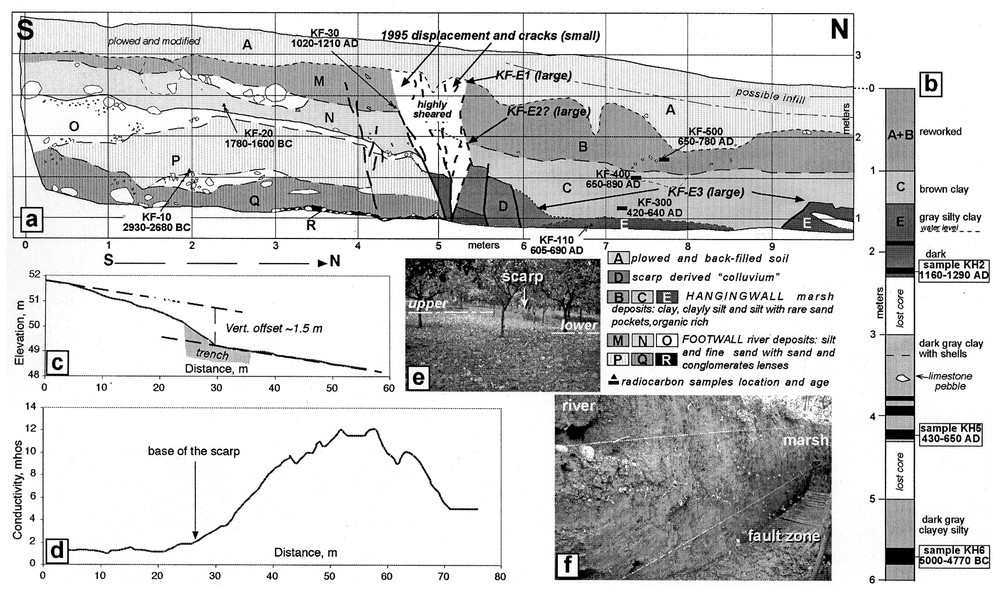

Le site (KF) de la tranchée et de la carotte est localisé à la sortie est du village d'Agios Kostantinos (Fig. 1), où une rupture de surface de quelques centimètres s'est produite lors du séisme de 1995 [10]. À cet endroit, l'expression morphologique de la faille est ténue, en raison de la jeunesse des dépôts et du transfert de l'activité tectonique sur d'autres branches de la faille, vers le nord. Les profils topographiques et électriques réalisés montrent d'importantes anomalies (Fig. 3). Celles-ci coı̈ncident avec les ruptures de surface du séisme de 1995 et avec la zone faillée de 2 m de large mise à jour par la tranchée. La zone de faille met en contact des dépôts alluviaux et de marais. L'interprétation stratigraphique et structurale de la tranchée a permis d'isoler trois événements avec des rejets décacentimétriques plus importants que les déplacements liés au séisme de 1995. Un carottage a été réalisé 2 m au nord de la tranchée dans les dépôts de marais, dont le sommet est corrélé avec les formations de la tranchée.

KF site. Simplified map of the west wall of the trench from a 1:20-scale survey (a) and diagram of the core (b). Black arrows in (a) indicate the location of the event horizons (i.e., the ground surface at the time of an earthquake): KF-E1, KF-E2 and KF-E3. Detailed topographic profile (c) and electrical profile (d) across the scarp; photo view of the scarp (e) and of the west wall of the trench (f). Ages of radiocarbon samples are -dendro-chronologically corrected [13].

Site KF. Carte simplifiée de la paroi ouest de la tranchée levée au 1:20e (a) et log de la carotte de forage (b). Les flèches noirs en (a) indiquent les horizons repères (c'est-à-dire la surface topographique lors des événements sismiques) KF-E1, KF-E2, KF-E3. Profils topographique détaillé (c) et électrique (d) à travers l'escarpement ; photographie de l'escarpement (e) et de la paroi ouest de la tranchée (f). L'âge 14C des échantillons est indiqué selon l'intervalle , corrigé d'après les données dendrochronologiques [13].

En utilisant les âges les plus jeunes obtenus pour les dépôts de marais dans la tranchée et dans la carotte, on conclut à la présence de trois événements après 1160 AD. Selon les descriptions des dégâts des séismes historiques [12], le séisme de 1888 peut s'être produit sur la faille d'Aigion. Cette date peut être considérée comme l'âge minimum de l'événement KF-E1. Cela entraı̂nerait un temps de retour moyen de 360 ans (trois événements entre 1160 et 1888 AD). Les contraintes sur les âges disponibles et les corrélations stratigraphiques fournissent une base pour estimer aussi les taux de déplacements verticaux de 2,4–2,5 mm a−1 durant les huit ou neuf derniers siècles. Des taux de rejets minimaux, basés sur la subsidence relative, peuvent être déduits des âges et de la profondeur de la carotte (2,1–2,5, 2,4–2,8, et 0,7–0,8 mm a−1, en utilisant les âges respectifs des échantillons).

Les taux de déplacement sur la faille peuvent être déduits des taux de subsidence transformés en taux de glissement, en supposant un rapport surrection/subsidence de 1:3, dérivé des modèles classiques de dislocation, et en utilisant un pendage de 60° pour la faille. Sur cette base, on obtient des taux de glissement de 1,6–2,3 mm a−1, avec des maxima jusqu'à 6,3 mm a−1 pour le site AFC et de 2,7–4,3 mm a−1 pour le site KF. Ces valeurs sont considérées comme des minima, car elles sont déduites d'observations de surface sur la faille.

Sur la base de l'ensemble des valeurs de longueur de faille et de déplacements moyens, les relations empiriques de Wells et Coppersmith [17] suggèrent que des séismes de magnitude 6,5 peuvent se produire sur la faille d'Aigion.

1 Introduction

The Corinth Gulf in Central Greece (Fig. 1) is a region of very fast crustal extension with measured rates of as much as 10–15 mm yr−1 in a ∼north–south direction during the past 100 yr [4,5]. Evidence of this high ongoing rate of deformation is the intense seismic activity that characterizes the entire Gulf. The 1981 Corinth earthquake sequence and the 1995 Aigion earthquake are the most recent damaging events (Fig. 1). Major structures responsible for the gulf seismicity are thought to be the several prominent normal faults that bound the gulf to the south: the Aigion Fault is one of these. Unfortunately, because of the limited information on historical earthquakes in the area [1,12] unequivocal association with a specific seismic event exists only for the Eliki and Skinos Faults. The eastern portion of the Eliki Fault ruptured in 1861 producing at the surface a clear, at least 15-km-long scarp, as much as 1 m high [15]. The Skinos Fault ruptured during one of the first shocks of the 1981 Corinth earthquake sequence and surface faulting was observed inland for a distance of about 20 km and had as much as 1.5 m of vertical throw [7,9]. The 1748 and 1888 [12] earthquakes damaged the Aigion area, allowing the possibility that both or one of them occurred on the Aigion Fault. The long-term seismic behaviour of the faults in the Gulf of Corinth is even more obscure: the few existing studies of the Skinos and Eliki Faults show that large-surface-faulting earthquakes repeat with intervals of 300 to 1000 yr on the individual faults and that vertical slip rates do not exceed 4 mm yr−1 [3,7,11]. In 1995, a M6.2 earthquake occurred about 15 km to the NNE of Aigion, on a low-angle normal fault. Although seismological, GPS and SAR data show that the 1995 seismogenic fault is far from and not related to the Aigion Fault, the occurrence of small coseismic ruptures along the Aigion Fault trace raised an important debate [2,10]. Whether the slip at the surface was sympathetic or due to compaction of soft, unconsolidated sediments still remain unsolved.

It is clear that there is a strong need for the characterization of seismogenic faults in order to fully understand the seismogenic processes taking place in the Corinth Gulf and to base seismic-hazard evaluations on solid observations. In this paper, we attempt to understand the seismic behaviour of the Aigion Fault through palaeoseismological investigations. We present the results of the study of a trench, a core and an artificial exposure across the fault in our attempt to date palaeoearthquakes and estimate slip rates.

2 The Aigion Fault

The Aigion Fault is part of a set of large north-dipping normal faults that bound the southern side of the Gulf of Corinth (Fig. 1). These faults form a continuous right-stepping system, with steps between the Eliki, Aigion, and Psatopyrgos faults being the most prominent. On the basis of geomorphic and structural characteristics, these steps represent geometric/structural barriers that control the fault extent and help to define the segmented nature of the system [6,14].

The Aigion Fault has a clear geomorphic expression in its middle part, where it forms a steep escarpment as much as 150 m high (Fig. 1). Marine oxygen isotope stage 5e marine platforms on top of the escarpment are raised because of footwall uplift, suggesting an uplift rate of 1.2 mm yr−1 [8]. Further east, the fault enters young deposits of the Selinous River delta, where it diminishes to a ca. 1-m-high scarp both because of the young age of the delta (not enough time is elapsed to allow the fault to express itself on the topography) and of the competition of fast alluvial processes versus tectonics. A possible 3-km-long extension of the fault offshore to the east is imaged through sonar surveys [16]. West of the Meganitas River, the fault geomorphology becomes subtle and the main fault is paralleled by other minor faults that form a complex step-over. Scarps on young delta sediments along the Fassouleika and Selianitika faults may represent splays of the westernmost portion of the Aigion Fault. On the basis of these observations, the minimum length of the Aigion Fault is about 14 km.

During the 1995 earthquake open cracks were observed along or close to the trace of the Aigion Fault; these cracks had a maximum vertical throw of 3 cm along the central and western part of the fault [10]. Liquefaction occurred along the fault trace, making it even harder to understand the significance of the coseismic ruptures.

The geomorphic, geologic and geophysical studies of the fault in the Aigion area are quite difficult because of intense geographic and cultural modifications due to human activities. This limits substantially the information that can be collected on the most recent history of Aigion Faulting. As a consequence, we found only one favourable site for trenching near the village of Ag. Kostantinos (KF, Fig. 1), but had the lucky chance to use an artificial cut not far from the town of Aigion (AFC, Fig. 1).

3 The Fruit Factory (AFC) site

A large construction excavation for a fruit factory, located just west of the town of Aigion (AFC, Fig. 1B), was studied in detail because it exposed the Aigion Fault (Fig. 2). At this location, the fault's long-term geomorphic expression is very clear: it forms a steep slope with incised V-shaped valleys feeding small alluvial fans (Fig. 1B). Unfortunately, significant modification of the ground surface (unit A), including removal of the upper parts of young fan and colluvial deposits, prevents the complete recording of the most recent fault activity. The section exposes about 4 m of colluvium (units F, G, L, M, P, T) that were deposited against the main fault plane (Fig. 2). This contact is marked by a 10–15-cm-thick layer of reddish oxidized and sheared deposits (unit Y). The footwall of the fault is comprised of typical fan delta gravel and sand (units X, Z). The fault zone is about 5-m-wide and produces a staircase-like deformation of all the sediments. All of the colluvial layers show an uncommon increase of their steepness away from the slope; this is interpreted as an effect of secondary faulting.

The colluvial layers show a high degree of internal complexity and variability, thus correlation and mapping contains large uncertainty. Most of these layers are composed of pebbly sand and silt with sparse gravel, organic matter and common oxidation. Alluvial sand and gravel, probably related to the alluvial fan that was located nearby the excavation, is exposed in the northern part of the section (unit H). Radiocarbon dating of the organic-rich deposits yielded dendrochronologically corrected ages that are reported in Fig. 2. Stratigraphic inversions of ages are a possible result of inclusion of reworked material.

Assuming that colluvial deposition is a direct result of slip on the fault (and not deposition from landscape change), this section appears to have potential mainly for slip-rate estimate. In fact, we may infer a minimum offset rate at this site on the basis of the estimate of the thickness of the colluvial sequence on the hangingwall and its maximum age. We estimated the thickness of the colluvium by projecting its layer's attitude to the main fault plane and by measuring its maximum thickness exposed in the section by excluding the modified portion. Taking the most obvious and oldest wedge-shaped colluvium (unit P) we reconstructed a thickness of 2.5–3.5 m and obtained a minimum offset rate of 0.3–0.4 mm yr−1 using the age determined from sample AFC-2 (5890–5720 BC). This is the lowest minimum rate, because it does not include the record of the slip on the secondary staircase splays. Following the same reasoning but using unit M and sample AFC-11, we obtained a minimum offset rate of 1.0–1.5 mm yr−1. This is in good agreement with the 1.1–1.4-mm yr−1 value obtained for unit G sample AFC-4, whereas much larger value of 2.7–4.1 mm yr−1 was obtained by using sample AFC-3. If no contamination from young material occurred, this latter value should represent the maximum slip rate on the Aigion Fault at this site.

Because of the lack of correlative deposits on both sides of the fault and the high variability in geometry and composition of colluvial deposits, it is very hard to use the AFC section to determine the timing of individual faulting events. However, we made an attempt by using the geometry of layers, their gradation, and comparable amounts of deformation. The oldest event (AFC-E3) is recognized at the base of unit P, because this unit is interpreted as a typical colluvial wedge and because several fault splays seem to terminate in older units (T, Z). A younger event AFC-E2 may have occurred after deposition of unit L, where an important change in the attitude of the beds occurs (the steepening of the colluvium away from the fault is not present in the younger units) and alluvial deposition (unit H) is suggestive of local subsidence attracting the river close to the scarp. A third event horizon (AFC-E1) is tentatively placed within unit G because of warp and sharp contacts that aligned with faults lower in the central zone of shearing. On this basis, we suggest the occurrence of at least three events with 0.6 to 1 m throw each during the past eight millennia (8 kyr). The age of the youngest one (AFC-E1) remains uncertain because of the unresolved ages determined from samples AFC-4 and AFC-3. Considering alternate possibilities, AFC-E1 may have occurred just before 670–870 AD or very close to 1440–1640 AD. Because the upper part of the section was missing, we could not define the most recent surface-faulting event of the Aigion Fault nor observe the 1995 earthquake cracks.

4 The Agion Kostantinos (KF) site

This site is located just east of the village of Agios Kostantinos (Fig. 1), where surface ruptures of a few centimetres height formed during the 1995 earthquake [10]. At this location, the geomorphic expression of the Aigion Fault is subtle (Fig. 3), both because of the youthfulness of the deposits and because part of the deformation has been transferred to parallel fault branches to the north.

Topographic and electrical profiles (Fig. 3c and d) made at the site show evidence of important anomalies. Although some regarding of the scarp was done for agricultural purposes, there is a clear change in conductivity across the west-trending, north-facing, scarp, which is as much as 1.5 m high. We opened a trench across the scarp and exposed a clear 2-m-wide fault zone coincident with the location of the 1995 ground ruptures and of the anomalies shown by the topographic and electric profiles.

This fault zone places alluvial deposits of the Meganitas River on the footwall (units M to R) in contact with marsh deposits on the hangingwall (units B, C, E). There are sheared deposits containing a mixture of both sediments in the fault zone along with scarp-derived deposits (unit D). Based on structural and stratigraphic relations, we have evidence for three surface faulting events with throws of tens of centimetres, substantially larger than the 1995 displacement. Evidence for the older event (KF-E3) is the presence of a scarp-derived deposit (unit D), of marsh infill (unit C), and of offset of unit E by the antithetic fault. A more recent event KF-E2 is shown by faulting of unit D, warping of unit C against the scarp and deposition of a new marsh sequence (unit B). Because the subvertical shear zone continues up to the top of unit B, we infer that one more event occurred after or during deposition of unit B. Coseismic vertical displacement cannot be measured univocally because no correlative layers cross the fault zone. The thickness of the marsh-filling (units B, C) and of the colluvial wedge (unit D) may provide minimum estimates of offset. The colluvial wedge suggests that a minimum of 0.5-m vertical slip occurred during KF-E3, whereas unit C, presumably filling the coseismic depression, indicates a net vertical offset of ca. 0.4 m. Similarly, by using the thickness of unit B, we obtain a vertical offset of ca. 0.7 m in event KF-E2. Because the scarp is strongly modified (see Fig. 3c), a value of ca. 0.4 m for the displacement for the KF-E1 can be inferred only by subtracting the two previous estimates from the net stratigraphic throw.

The core was taken ca. 2 m north of the trench – it reached a depth of 6 m and penetrated a marsh sequence whose upper part is well correlated with the trench exposure (units B, C, and E). Most of the deeper deposits were clayey silt, locally rich in organic matter (Fig. 3b).

We dendrochronologically corrected [13] radiocarbon-dated samples collected from both the trench and core. The alluvial deposits on the upthrown block (units M-R) yielded ages between 2930 BC and 1210 AD. After 1210 AD, limited overbank deposition occurred (unit M). The correlative river deposits on the downthrown block are probably buried under the marsh deposits, but the core did not reach them. The marsh deposits are consistently younger, with ages ranging between 1290 AD and 420 AD with exception for the deepest sample collected in the core, which yielded a problematic age of 4770–5000 yr BC. This dating is likely too old owing to inclusion of old organic material reworked from the scarp. By using the youngest age obtained for the faulted marsh deposits (KH-2), we can conclude that the three events occurred after 1160 AD. According to historical earthquake damage descriptions [12] the 1888 earthquake could have occurred in the Aigion Fault. This date should be thus taken as the minimum age date for KF-E1. This would suggest a maximum average recurrence interval of 360 yr (three events between 1160 and 1888 AD). The available age constraints provide a basis for estimating slip rates. Units containing samples KF-30 and KH-2 show sedimentological similarities; because their ages overlap and they show a ca. 2 m separation across the fault, we can use them to estimate a 2.4–2.5 mm yr−1 vertical slip rate during the past 8–9 centuries. Minimum offset rates, based on relative subsidence can also be inferred by using age and depth of the core samples assuming that the upper 0.5 m may be artificial infilling of the scarp. We obtain 2.1–2.5, 2.4–2.8, and 0.7–0.8 mm yr−1 using the ages from samples KH-2, KH-5 and KH-6, respectively. We suggest the smallest figure is due to a contamination of sample KH-6 instead being evidence of a change in slip rate. In fact, if the age of KH-6 is correct, the core should have penetrated younger river deposits correlative with those exposed in the footwall.

5 Conclusions

Our excavation and studies of a trench, a core and an artificial exposure at two sites along the Aigion Fault (Fig. 1) allow us to place some preliminary constraints on the fault's short-term seismic behaviour. The maximum fault length is about 14 km and it has a 60°N near-surface dip, as measured in the AFC exposure. Net slip rates are derived from estimates of offset rates assuming they represent the subsidence component of the vertical rates, and assuming a uplift: subsidence ratio 1:3, as derived by common dislocation models, and using the 60° dip of the fault. On this basis, and using the most conservative estimates, we obtain slip rates of 1.6–2.3 mm yr−1, with maximum up to 6.3 mm yr−1, and 2.7–4.3 mm yr−1 at AFC site and at KF site, respectively. These values are expected to be minima, because they are derived only from surface observations on the fault. Dating of the most recent surface-faulting earthquake is debatable. From AFC site, it could be as young as 1440–1640 AD, but because of the site modification, it may not represent the true last surface-faulting event of the Aigion Fault. Three events with vertical throws of 0.4–0.7 m each that occurred between 1160 AD and 1888 AD are recognized at KF: they yield a maximum inter-event interval of 360 yr. No evidence for prior 1995-type deformation can be found in this type of sediments, because their small offsets are within the uncertainty of observation and likely were overprinted by the larger events. On the basis of the observed surface fault length and average displacement, the empirical relations of Wells and Coppersmith [17] suggest that the Aigion Fault is capable of M 6.5 earthquakes.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mr K. Fakas (owner of the KF site) and to the AFC site management for granting access to and use of their properties for the palaeoseismological investigations, and, in addition, Dr E. Kollia for releasing the archaeological permit to perform the excavation, G. D'Addezio for field support and discussions, M. Machette, H. Philip and E. Baroux for their thorough reviews that helped improving the manuscript. This work was funded by EC project CORSEIS (EVG1–1999–00002) with additional contributions by INGV and IRSN.