Version française abrégée

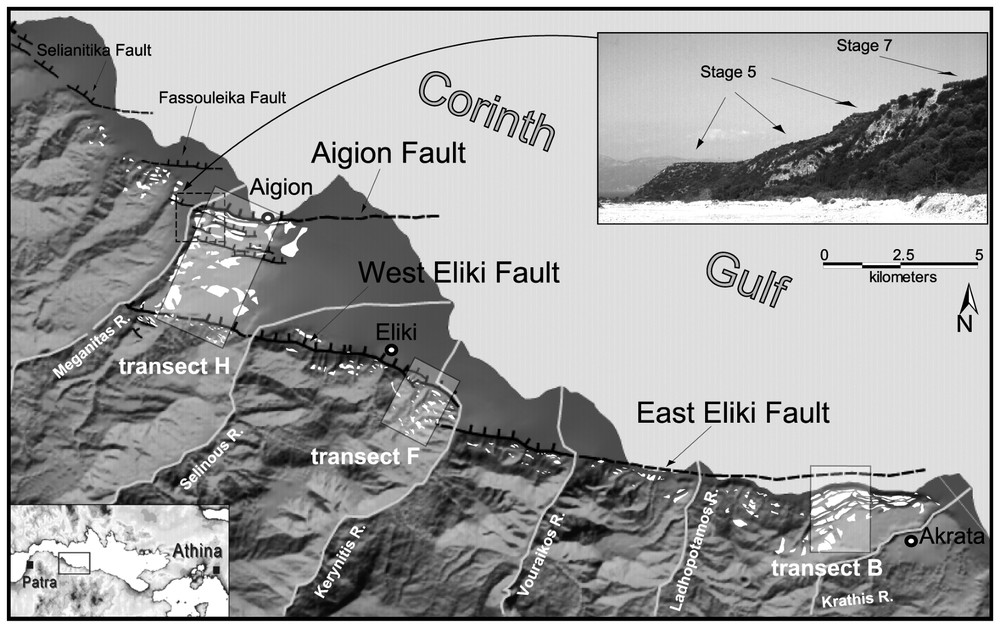

Le golfe de Corinthe (Fig. 1) est caractérisé par une importante sismicité historique et instrumentale [2]. Les déplacements calculés par GPS [4,5] indiquent que la région présente un des taux d'extension les plus rapides dans le monde (10–15 mm an−1). Les données macrosismiques et instrumentales fournissent des valeurs maximales de magnitude de l'ordre de 6,6 à 6,8 [2]. Des ruptures de surface sont mentionnées pour certains séismes majeurs (par exemple, 1861 et 1981). Cette étude porte sur la rive sud du golfe de Corinthe, qui est bordée par des failles majeures est–ouest en échelons, avec plongement nord (Fig. 1). L'activité récente de ces failles est attestée par des signes géologiques et géomorphologiques [3,12], avec un importante surrection indiquée par les terrasses marines du Pléistocène supérieur [3,8,11]. Notre étude est localisée entre Aigion et Akrata, où des restes de terrasses ont été cartographiés dans les compartiments mur des failles d'Aigion et d'Eliki (Fig. 1), dans le but d'obtenir des taux de surrection fiables sur le long terme. L'objectif final de ce travail est de convertir toutes les données provenant d'indicateurs de mouvement vertical durant l'Holocène ou le Quaternaire récent en taux de déplacement à long et moyen terme, par l'utilisation d'un modèle de dislocation.

DEM of the study area and main active faults; the three selected marine terraces transects are also shown. Lower left inset: location of the study area. Upper right inset: view of the terraces on the Aigion Fault footwall, from the Meganitas River valley looking northeast.

MNT de la région étudiée et failles majeures : les trois transects sélectionnés des terrasses marines sont reportés dans les rectangles. Le schéma en bas à gauche montre la localisation régionale. La photo à droite représente les terrasses préservées sur le mur de la faille d'Aigion, à partir de la vallée du fleuve Meganitas, en regardant vers le nord-est.

Le rift du golfe de Corinthe a un allongement général ESE–WNW. Il présente une forme de demi-graben, constitué au sud de plusieurs systèmes de failles normales majeures en échelon plongeant vers le nord. Ces failles sont associées à des escarpements spectaculaires le long de la côte sud du golfe. Une migration générale de l'activité tectonique du sud vers le nord a été montrée par des études géologiques et géomorphologiques [3] et semble confirmée par la distribution de la sismicité [2,7]. Un très bon exemple de migration récente est fourni par le système en échelons des failles d'Eliki et d'Aigion. Le système de la faille d'Aigion, composé des failles d'Aigion, de Fassouleika et de Selianitika (Fig. 1), chevauche la partie occidentale du système de la faille d'Eliki, qui est distant de 4 km.

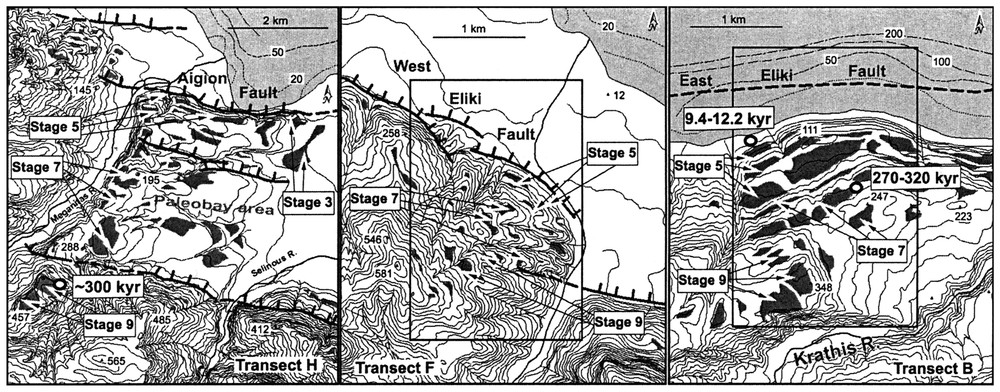

Dans le compartiment mur des failles d'Eliki et d'Aigion, l'existence de restes plus ou moins bien conservés de terrasses, pour la plupart marines, est évidente dans la topographie, où ils correspondent à des surfaces planes légèrement inclinées vers la mer. Le lever de ces surfaces et la détermination des altitudes extrêmes ont été entrepris au moyen de cartes topographiques détaillées, de photos aériennes et d'observations de terrain (Fig. 2). Les terrasses les plus importantes sont présumées s'être formées durant les stades de haut niveau marin, comme cela est le cas à l'est dans la zone de Corinthe–Xylokastro [3,8]. Durant les campagnes de terrain, l'effort a porté sur l'identification des dépôts marins dans les surfaces cartographiées et sur l'échantillonnage de matériel susceptible d'être daté afin d'obtenir un contrôle des âges absolus pour les terrasses. Pour certaines surfaces, une origine fluviale est suggérée par leur environnement morphologique, l'altitude de leur limite interne pouvant être assimilée à un équivalent possible de niveau marin, sous réserve que les hauts niveaux marins soient propices à la formation de terrasses fluviatiles majeures.

Map of marine terraces and fluvial surfaces in three transects on the Eliki and Aigion Fault footwalls. Boxes indicate the tentative correlation of marine terraces with major highstands from the Late-Pleistocene eustatic sea-level curve. The location of the available dating (open circles) discussed in the text has been projected from the original location in transect B, whereas in transect H the dating (open circles) locations are the true ones. Contour interval is 20 m.

Carte des terrasses marines et des surfaces fluviatiles dans les trois transects au travers du mur des failles d'Eliki et d'Aigion. Les indications « stage » représentent les tentatives de corrélation entre les terrasses marines et les hauts niveaux marins des courbes eustatiques au Pléistocène supérieur, pour les trois transects B, F et H. Dans le transect B, on a projeté la position des datations (cercles blancs) sur la terrasse correspondante. Au contraire, les datations (cercles blancs) du transect H occupent la position originale. L'intervalle des courbes de niveau est de 20 m.

L'ensemble des terrasses les mieux préservées est localisé dans le secteur d'Akrata. Jusqu'à sept terrasses ont été distinguées dans le compartiment mur de la faille d'Aigion jusqu'à une altitude de 230 m. La distribution de ces surfaces suggère l'existence d'une paléobaie entre les failles d'Eliki Ouest et d'Aigion (Fig. 2). Les zones où les terrasses marines sont nombreuses et les mieux préservées ont été sélectionnées pour chaque faille. Les contraintes chronologiques disponibles sont rares pour corréler l'ensemble des terrasses avec les courbes de niveau eustatique (Fig. 2).

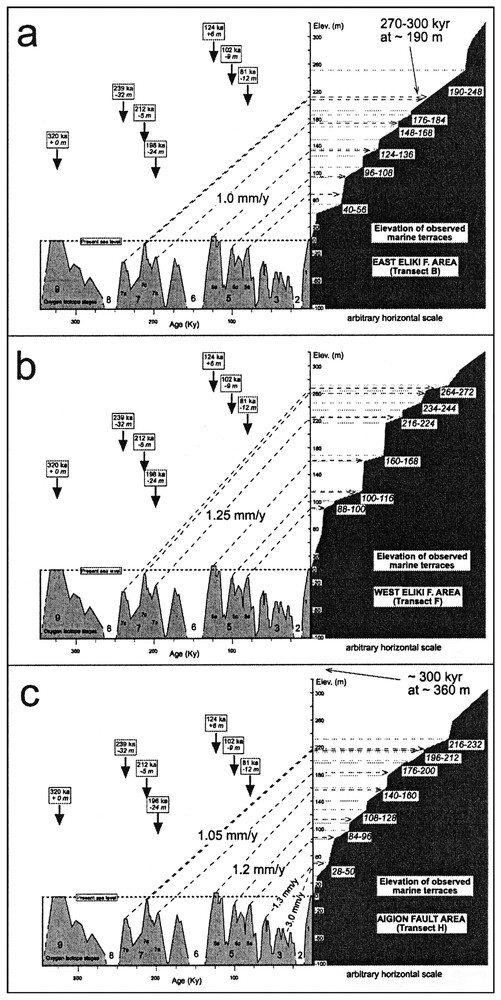

Malgré les incertitudes sur les datations des surfaces, une tentative de corrélation des terrasses a été entreprise avec les hauts niveaux marins des courbes eustatiques du Pléistocène supérieur [9] pour des coupes sélectionnées, dans le but de calculer des taux de surrection des compartiments mur de différentes failles (Fig. 3). Lors de ces corrélations, les éléments suivants sont pris en compte : (a) le faible nombre de datations de bivalves et de coraux échantillonnés à différentes altitudes dans les terrasses d'âges Holocène et Pléistocène supérieur [10,11,15] ; (b) les sous-séquences de terrasses rencontrées à des altitudes de 90–150 m et 180–250 m peuvent être considérées comme des multiples des hauts niveaux marins des stades 5 et 7 [11]. Sur cette base, on obtient des taux de surrection cumulés sur le long terme de 1,0, 1,25 et 1,05–1,2 mm an−1 pour les derniers 200–300 ka, respectivement pour les compartiments mur des failles d'Eliki partie est, partie ouest et d'Aigion. Ces valeurs incluent la composante régionale de la surrection, qui est estimée de l'ordre de 0,2 mm [6], ou au maximum 0,3 mm an−1 [3].

Long-term cumulative uplift rates, calculated along transects B, F and H on the East Eliki, West Eliki and Aigion Faults footwalls, respectively. These are obtained by correlating the elevations of marine terraces with highstands from Late-Pleistocene eustatic sea-level curve [9]. The horizontal scale is arbitrary.

Taux de déplacement cumulés sur le long terme, calculés sur les transects B, F, et H pour les murs des failles d'Eliki est et ouest et la faille d'Aigion. Les taux ont été obtenus par corrélation des altitudes des terrasses marines avec les hauts niveaux marins des courbes eustatiques du Pléistocène supérieur [9]. L'échelle horizontale est arbitraire.

Pour traduire en taux de déplacement les taux de surrection obtenus à différents endroits dans le compartiment mur d'une faille, on utilise un modèle de dislocation basé sur un code développé par Ward et Valensise [17], avec des paramètres prédéfinis pour chaque faille. Pour obtenir ces taux et aussi d'autres portant sur le Quaternaire récent, un calage a été réalisé sur certaines coupes. Pour les derniers 200–300 ka, on obtient des taux maximums de déplacement de 7–11 mm pour les failles d'Eliki est et ouest et de 9–11 mm an−1 pour la faille d'Aigion, avec une hypothèse de surrection régionale de 0,2 mm an−1 [6]. Les résultats obtenus avec ce modèle ont été comparés avec les modèles mécaniques plus complexes proposés par Armijo et al. [3] pour la faille de Xylokastro, dans la partie centrale du golfe. Les failles étudiées semblent donner chacune une contribution de 4 à 7 mm an−1 pour l'extension nord–sud de la partie ouest du golfe de Corinthe. En conséquence, elles peuvent accommoder au maximum 50 % de l'extension calculée par la géodésie dans cette région [4,5].

1 Introduction

The Corinth Gulf in Greece (Fig. 1, inset) is characterised by intense historical and instrumental seismicity [2, and references therein]. Current rates of extension that have been geodetically determined across the Gulf [4,5] suggest this region is one of the most rapidly extending continental areas in the world, with the highest velocity observed at its western end (10–15 mm yr−1 of north–south-oriented) extension. Instrumental seismicity and macroseismic data in the Corinth Gulf area constrain the maximum observed earthquake magnitude in the range 6.6–6.8 [2]. Surface faulting has been reported for some major earthquakes (e.g., 1861 and 1981) in the Corinth Gulf area (see [1,2] for a summary). In this study, we concentrate on the southern side of the Gulf of Corinth, which is bounded by major east–west-striking en-echelon normal faults [3] (Fig. 1). Recent activity of these faults is testified by direct geological and geomorphic evidence [3,12]. In fact, along the southern shore, important coastal uplift is well depicted by raised Late Pleistocene marine terraces [3,8,11]. Our study area is located between Aigion and Akrata, where terrace remnants were mapped on the footwalls of the Aigion and Eliki Faults (Fig. 1), in order to obtain reliable estimates of long-term uplift rates. The final purpose of this work is to translate all the available Holocene and Late-Quaternary indicators of vertical movements into long- and mid-term fault slip rates by means of dislocation modelling.

2 Geomorphology

2.1 Main active faults

The Corinth Gulf Rift has a general ESE–WNW trend and shows an asymmetric shape with an uplifted southern footwall, where a series of main north-dipping en-echelon normal fault systems is associated with spectacular escarpments along the southern coast of the gulf. A general migration of tectonic activity from the southernmost to the northernmost faults has been demonstrated by geomorphic and geologic studies [3, and references therein] and seems to be confirmed by the distribution of seismicity within the Gulf [2,7]. This migration of tectonic activity towards the north is manifested by the inception of new faults a few kilometres to the north of the pre-existing ones, a process occurring together with a progressive northward strain transfer. A very good example of recent migration is the case of the east–west-striking, north-dipping Eliki and Aigion Fault systems.

On the basis of escarpment geometry and the distribution of the 1861 earthquake ruptures as described by [14], the Eliki Fault system (f.s.) can be divided in two main segments, referred to as the East and West Eliki Faults. Both segments are ∼15 km long, and are separated by a right-stepping transfer zone located at the longitude of the Kerynitis River (Fig. 1).

The detailed morphology depicted in maps around the main Aigion escarpment, together with field observations suggest that the Aigion Fault system consists of a set of en-echelon strands, apart from the main Aigion Fault, the largest ones being those of Fassouleika and Selianitika (Fig. 1). The Aigion escarpment – the largest of the Aigion f.s. – is much smaller in length and elevation compared to that of the Eliki Fault, plus, it is developed in younger deposits in the hanging wall of the latter, indicating it is a younger structure. The Aigion f.s. overlaps with the western part of the Eliki f.s., from which it is separated by about 4 km (Fig. 1).

2.2 Marine terraces

On the footwall of the Eliki and Aigion Faults, the existence of flights of more or less preserved marine terraces is evident in the topography, corresponding to flat or gently seaward-dipping surfaces. Mapping of these surfaces and determination of inner and outer edge elevations were undertaken on very detailed 1:5000 topographic maps of the Hellenic Army Geographical Service (HAGS), air photos, and field survey (Fig. 2). The errors in elevation estimates for the surfaces are evaluated as less than ±10 m.

Prominent marine terraces can be assumed to have formed during sea-level highstands, as has been the case with marine terraces farther east, in the Corinth–Xylokastro area [3,8]. During field survey, effort was put to the recognition of marine deposits on the mapped surfaces, and in sampling of datable material in order to obtain absolute age control for the terrace sequence. Littoral deposits were found in relatively few surfaces, firmly establishing these as marine terraces, whose inner edges correspond to highstand shorelines. For some of the surfaces, fluvial origin is suggested by their morphological surroundings, their outer edge elevation being of use as a possible sea-level proxy, under the assumption that the formation of major fluvial terraces was favoured during highstands.

For several surfaces, the available morphological and field data were inconclusive, whereas further uncertainties in terrace mapping are introduced by the existence of small faults that probably fragment larger surfaces into smaller ones at different elevations, e.g., in transect H south of Aigion, or transect F, which is in the step-over between the West and East Eliki Fault, where surface remains are very small and the existence of small faults is suggested by the detailed topography.

On the West and East Eliki Faults escarpments, a maximum of ten marine terraces were mapped up to an elevation of 500 m a.s.l., and as far as 2 km south of the fault [11]. The best-preserved flight of terraces is found in the Akrata area (transect B). Up to seven terraces can be distinguished on the footwall block of the Aigion Fault up to a maximum elevation of 230 m a.s.l. These surfaces are distributed as far as 4 km to the south, in an arrangement suggesting the existence of a palaeo-bay in-between the West Eliki and Aigion Fault escarpments (Fig. 2).

3 Vertical tectonic movements deduced from uplifted marine terraces

The areas where the marine terraces are largest in number and relatively better preserved were selected for each fault (transects B, F, H for the East Eliki, West Eliki and Aigion Fault respectively; Fig. 2).

Only few chronological constraints are available to substantiate a correlation of the terrace sequences with the eustatic sea-level curve. McNeill and Collier [11] have dated coral samples collected from a terrace near Akrata (eastern end of the East Eliki Fault, close to our transect B; Fig. 2) at an elevation of about 190 m a.s.l. Considering measured U-series ages on multiple samples of 270–320 kyr, problems related to diagenetic alteration of the corals and probable reoccupation of the terrace during a later highstand, the authors assigned this surface to Stage 7c. Stewart [15] obtained ages of 9.4–10.0 kyr and 9.8–12.2 kyr from emerged shoreline fauna located on the East Eliki Fault footwall (transect B in Fig. 2) at elevations of 10.3 m and 15.8 m (corrected for sea-level changes), respectively, thus suggesting a Holocene uplift rate of 1.0–1.6 mm yr−1. We obtained a U-series age close to 300 kyr (Stage 9) for marine shells collected at 360 m a.s.l. on the West Eliki Fault footwall (transect H in Fig. 2). Ostrea sp. shells found in some other locations are unfortunately not favourable for U/Th dating.

Even though there are uncertainties involved with surfaces included in the terrace dataset for reasons previously described, a tentative correlation with highstands from the Late Pleistocene eustatic sea-level curve [9] was attempted on selected transects in order to calculate footwall uplift rates for the respective faults (Fig. 3). In doing this correlation, we took into consideration: (a) the few available dating of bivalve and coral samples collected at different elevations on Holocene and Late Pleistocene terraces [10,11,15, and this work] and (b) the observation that two terrace sub-sequences show up at elevations ca. 90–150 m and ca. 180–250 m a.s.l., which, based on the available absolute ages, can be considered to correlate with multiple highstands of Stages 5 and 7 [11].

On this basis, we obtained long-term cumulative uplift rates of 1.0, 1.25 and 1.05–1.2 mm yr−1 over the past 200–300 kyr for the East Eliki, West Eliki and Aigion Fault footwalls, respectively.

We could not get a unique value for the Aigion Fault footwall, the terraces of Stage 5 having clearly emerged more rapidly (1.2 mm yr−1) with respect to those of Stage 7 (1.05 mm yr−1). This discrepancy can be attributed to different factors: (a) changing uplift rate through time, with a recent acceleration; (b) different distance from the fault, Stage 7 terraces being at a distance of 2–4 km, whereas those of Stage 5 are much closer (uplift is known to decrease with distance from a normal fault [17]); (c) activity of the West Eliki segment, which could negatively influence the coeval Aigion Fault footwall uplift (Fig. 1), especially the Stage 7 terraces that are the closest to the West Eliki Fault trace. Unfortunately, we do not have enough information and age control to discriminate between the above three factors and the extent to which they contributed to the observed discrepancy. More absolute dating will help in dealing with this problem in the future.

It should be taken into account that our calculated uplift rates include a component of regional tectonic uplift. Although not well constrained in the whole area of the Corinth Gulf, this is estimated to be in the order of 0.2 mm yr−1 [6] and less than 0.3 mm yr−1 according to [3]. Applying this correction, our best estimates of footwall uplift rates in mm yr−1 for each fault are listed in Table 1.

Best estimates of footwall uplift rates (mm yr−1)

Meilleures estimations du taux de déplacement du mur des failles (mm an−1)

| Fault | Footwall uplift rate (mm yr−1) |

| East Eliki Fault | 0.8 |

| West Eliki Fault | 1.05 |

| Aigion Fault | 0.85–1.0 |

The marked decrease in number and extent of uplifted terraces toward the west, across successive transects of the West Eliki Fault footwall (Fig.1), seems to suggest that its western part (between Selinous and Meganitas Rivers) has a much lower rate of activity. This important change is not seen on the East Eliki Fault footwall, where uplift rates estimated on six terrace transects show little change along strike [11]. Thus, from a morphotectonic point of view, the segment boundary set at the longitude of the Kerynites River mainly on the basis of the 1861 ruptures [14] could be questionable.

The aforementioned slower section of the West Eliki Fault overlaps with the Aigion Fault, suggesting that the inception of the latter deactivated, at least partially, the stretch of the West Eliki Fault located to its southwest. The existence of terraces in this area and the terrace ages that we propose provide a means to constrain the timing of the inception of the Aigion Fault, based on the fact that the oldest surfaces that are found on its footwall are of Stage 7. This suggests that this fault is at least 200–250 kyr old, and perhaps not much older than this figure. This age should also represent the beginning of the strain transfer from the West Eliki Fault to the Aigion Fault, under the assumption of constant amount of extension accounted by the active faults of the area. We do not know how the strain transfer between active faults occurs; more absolute dating of the marine terraces of transect H and integration with other data, such as those presented in [10], will help in dealing with this problem.

4 Cumulative long- and mid-term slip rates on the East–West Eliki and Aigion Faults

To translate the uplift rates obtained at different locations along the fault footwall to fault slip rates, we used dislocation models incorporating fault parameters based on fault mapping in the field, detailed topographic maps and air photos interpretation. A value of 7–8 km was adopted for the seismogenic thickness along the southern side of the Corinth Gulf, as proposed by recent seismological studies [13,16]. Fault parameters used in the calculation are listed in Table 2.

Fault parameters used in the calculation

Paramètres de failles utilisés pour le calcul

| Fault | Length (km) | Width (km) | Top (km) | Bottom (km) | Dip |

| East Eliki | 16.6 | 9.5 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 50° |

| West Eliki | 12.0 | 9.5 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 50° |

| Aigion | 10.0 | 9.5 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 50° |

In order to obtain fault slips, and thus Late-Quaternary slip rates, we adopted a forward modelling procedure to fit the selected transects B, F and H (Tables 3–6). Our calculations assume uniform slip on planar, rectangular faults embedded in an elastic half-space, and were performed with a code developed by Ward and Valensise [17], based on the standard dislocation theory. A summary of these long-term slip rates (over the past 200–300 kyr) for each fault segment, obtained under the assumption of a regional uplift rate of 0.2 mm yr−1 [6] is given in Table 3.

Summary of long-term slip rates in mm yr−1 (over the past 200–300 kyr) for each fault segment, obtained under the assumption of a regional uplift rate of 0.2 mm yr−1

Résumé des taux de glissement à long terme en mm a−1 (sur les derniers 200–300 ka) pour chaque segment de faille, obtenu dans l'hypothèse d'un taux de déplacement régional de 0,2 mm an−1

| Fault | Long-term slip rates (mm yr−1) |

| East Eliki Fault | 7–9 |

| West Eliki Fault | 9–11 |

| Aigion Fault | 9–11 |

East Eliki Fault – Transect B

East Eliki Fault – Transect B

| Terrace | Sea-level | Uplift-rate | Total slip | Slip rate | Slip rate |

| Elevation (m) | high-stand | (mm yr−1) | elastic-half space | (mm yr−1) | (mm yr−1) |

| 10.3 | 9.4–10 kyr BP | 1.0 | 85 | 8.5 | 6.8 |

| 15.8 | 9.8–12.2 kyr BP | 1.3 | 130 | 10.7 | 9.3 |

| average | 9.6 | 8.1 | |||

| 68 | 5a | 0.8 | 570 | 7.0 | 5.3 |

| 120 | 5c | 1.2 | 1000 | 9.8 | 8.2 |

| 132 | 5e | 1.1 | 1100 | 8.9 | 7.2 |

| average | 8.6 | 6.9 | |||

| 190 | 7a | 1 | 1700 | 8.7 | 6.9 |

| 190 | 7c | 0.9 | 1740 | 8.2 | 6.3 |

| 280 | 7e | 1.2 | 2560 | 10.7 | 8.8 |

| average | 9.2 | 7.3 | |||

| 306 | 9 low | 0.9 | 3200 | 9.6 | 7.6 |

| 360 | 9 high | 1.1 | 3760 | 11.9 | 9.7 |

| average | 10.8 | 8.7 | |||

| Corrected for | Based on the | Regional uplift | |||

| sea-level | distance from | of 0.2 mm yr−1 | |||

| changes | the fault |

West Eliki Fault – Transect F

Faille d'Eliki ouest – Transect F

| Terrace | Sea-level | Uplift-rate | Total slip | Slip rate | Slip rate |

| Elevation (m) | high-stand | (mm yr−1) | elastic-half space | (mm yr−1) | (mm yr−1) |

| 112 | 5a | 1.4 | 1070 | 13.2 | 11.3 |

| 125 | 5c | 1.2 | 1190 | 11.7 | 9.8 |

| 162 | 5e | 1.3 | 1540 | 12.4 | 10.5 |

| average | 12.4 | 10.5 | |||

| 248 | 7a | 1.2 | 2360 | 11.9 | 10.0 |

| 250 | 7c | 1.2 | 2380 | 11.2 | 9.3 |

| 304 | 7e | 1.3 | 2900 | 12.1 | 10.2 |

| average | 11.7 | 9.8 | |||

| 316 | 9 low | 1.0 | 3330 | 10.0 | 8.0 |

| 400 | 9 high | 1.3 | 4210 | 13.3 | 11.1 |

| average | 11.7 | 9.6 | |||

| Corrected for | Based on the | Regional uplift | |||

| sea-level | distance from | of 0.2 mm yr−1 | |||

| changes | the fault |

Aigion Fault – Transect H

Faille d'Aigion – Transect H

| Terrace | Sea-level | Uplift-rate | Total slip | Slip rate | Slip rate |

| Elevation (m) | high-stand | (mm yr−1) | elastic-half space | (mm yr−1) | (mm yr−1) |

| 105 | 3a? | 3.0 | 1050 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| 80 | 3e? | 1.3 | 800 | 13.3 | 11.3 |

| 108 | 5a | 1.3 | 1080 | 13.3 | 11.4 |

| 137 | 5c | 1.3 | 1370 | 13.4 | 11.5 |

| 154 | 5e | 1.2 | 1540 | 12.4 | 10.4 |

| average | 13.0 | 11.1 | |||

| 212 | 7a | 1.1 | 2550 | 12.9 | 10.5 |

| 232 | 7e | 1.0 | 2800 | 11.7 | 9.3 |

| average | 12.3 | 9.9 | |||

| Corrected for | Based on the | Regional uplift | |||

| sea-level | distance from | of 0.2 mm yr−1 | |||

| changes | the fault |

We tested this simple modelling procedure by comparing our results with those derived from more complex mechanical models proposed by Armijo et al. [3] for the Xylokastro Fault in the central Corinth Gulf. This comparison shows that, under identical hypothesis of 0.0, 0.2 and 0.4 mm yr−1 of regional uplift rates (see Fig. 20 in [3]), but without correction for erosion and deposition effects, their three models account for only 78, 68 and 64% of our rates calculated for Stage-5 terraces along transect B.

After this test, we are aware that by using a code based on standard dislocation theory [17], we are able to obtain the most conservative results, always representing the maximum slip rates for the modelled fault.

5 Conclusions

We mapped in detail raised Late-Pleistocene marine terraces preserved on the footwalls of the Aigion and Eliki Faults along the southern shore of the Gulf of Corinth. Even though few age controls are available, individual terraces at three sites where the sequences are best preserved have been tentatively correlated with the eustatic sea-level curve. We obtain best-fit cumulative uplift rates over the past 200–300 kyr of 1.05–1.2 mm yr−1 for the Aigion Fault footwall and of 1.0 and 1.25 mm yr−1 for the East and West Eliki Fault footwalls, respectively. From a more detailed analysis of all the uplifted terraces, we note that the western part of the West Eliki Fault shows a lower uplift rate, whereas little change in uplift rate is observed along-strike of the East Eliki Fault. Uplifted marine deposits 10 kyr old on the East Eliki Fault footwall indicate higher uplift rates with respect to those calculated over the past 200–300 kyr, thus suggesting a recent acceleration of the faults activity. A forward modelling procedure was adopted to fit the best preserved terrace transects on the fault footwalls of the three main fault segments. By using a code based on standard dislocation theory and considering the effect of the regional uplift, we obtained maximum slip rates consistently in the range of 7–11 mm yr−1 for the West and East Eliki Faults and of 9–11 mm yr−1 for the Aigion Fault. As a consequence, these faults should give a maximum single contribution to the extension across the western Corinth Gulf of about 4–7 mm yr−1. Given that the north–south-oriented, geodetically determined rate of extension across the western end of the Gulf [4,5] is in the order of 10–15 mm yr−1, about 50% is not accommodated by the activity of the onshore faults studied in the present work.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to D. Sorel and R. Armijo for interesting discussions in the field, to J. Jackson, an anonymous reviewer and E. Baroux for their through reviews that helped improving the manuscript. This work was funded by EC project CORSEIS (EVG1-1999-00002), with additional contributions by INGV and IRSN.