Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Dans les Alpes occidentales, le socle anté-alpin des unités penniques comprend des granitoı̈des plus ou moins déformés et des roches métasédimentaires [20,21,31]. La nature originelle des contacts entre granitoı̈des et roches métasédimentaires (à savoir stratigraphique, tectonique, ou intrusif) peut être difficile, voire impossible, à déterminer. Ce travail a pour objet de résoudre cette question dans le cas de l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet (Grand-Paradis).

2 Situation géologique

La partie nord du massif du Grand-Paradis (Fig. 1) présente deux grandes unités : l'unité du Grand-Paradis et l'unité du Money [19]. L'unité du Grand-Paradis est essentiellement constituée de granitoı̈des d'âge tardi-Hercynien [13,14], plus ou moins déformés, et de métasédiments contenant des reliques d'un épisode métamorphique de haute température, donc anté-alpin. Des reliques de métamorphisme de contact ont été préservées dans quelques paragneiss [12,17]. L'unité du Money (Fig. 2) est constituée d'un orthogneiss leucocrate (orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet) situé sous une épaisse série métasédimentaire. L'absence de reliques de métamorphisme de haute température et l'abondance du graphite dans les métasédiments de cette unité ont permis d'argumenter que cette unité est monométamorphique, et donc d'âge Permo-Carbonifère [19]. La nature du contact entre l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet et les métasédiments du Money est restée jusqu'à présent inconnue.

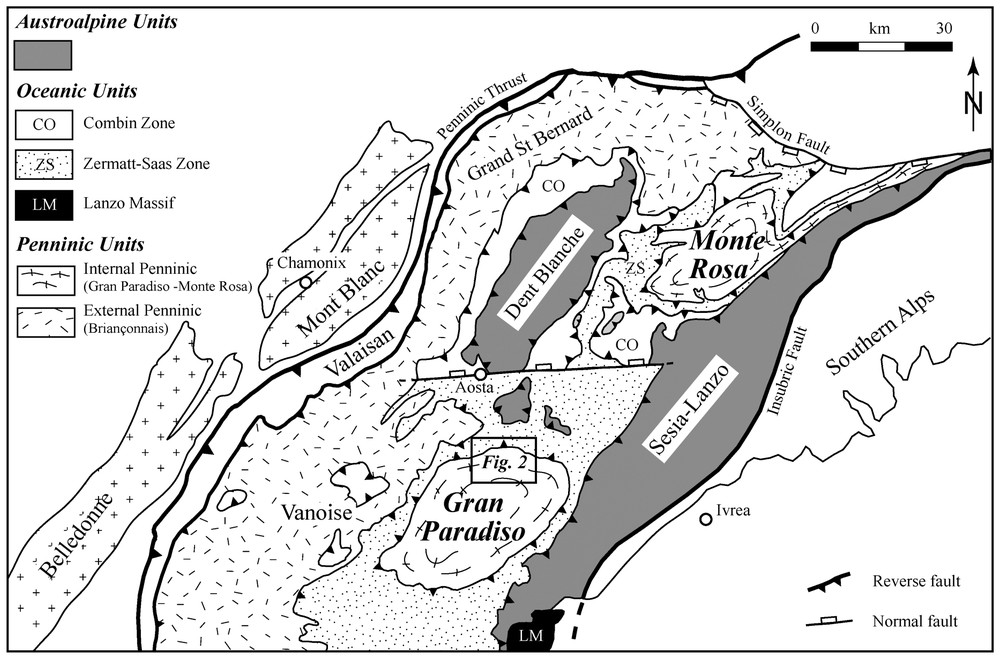

Simplified structural map of the northwestern Alps. The Gran Paradiso massif, like the Monte Rosa massif, is a tectonic window below the eclogite-facies units derived from the Piemont-Ligurian ocean (Zermatt-Saas Zone). Both massifs expose the pre-Alpine basement of the distal part of the palaeo-European margin.

Carte géologique simplifiée des Alpes du Nord-Ouest. Les massifs du Grand-Paradis et du Mont-Rose sont en fenêtre sous les unités éclogitiques dérivant de l'océan Liguro-Piémontais (Zermatt-Saas). Ces massifs montrent le socle anté-alpin de la partie distale de la paléo-marge européenne.

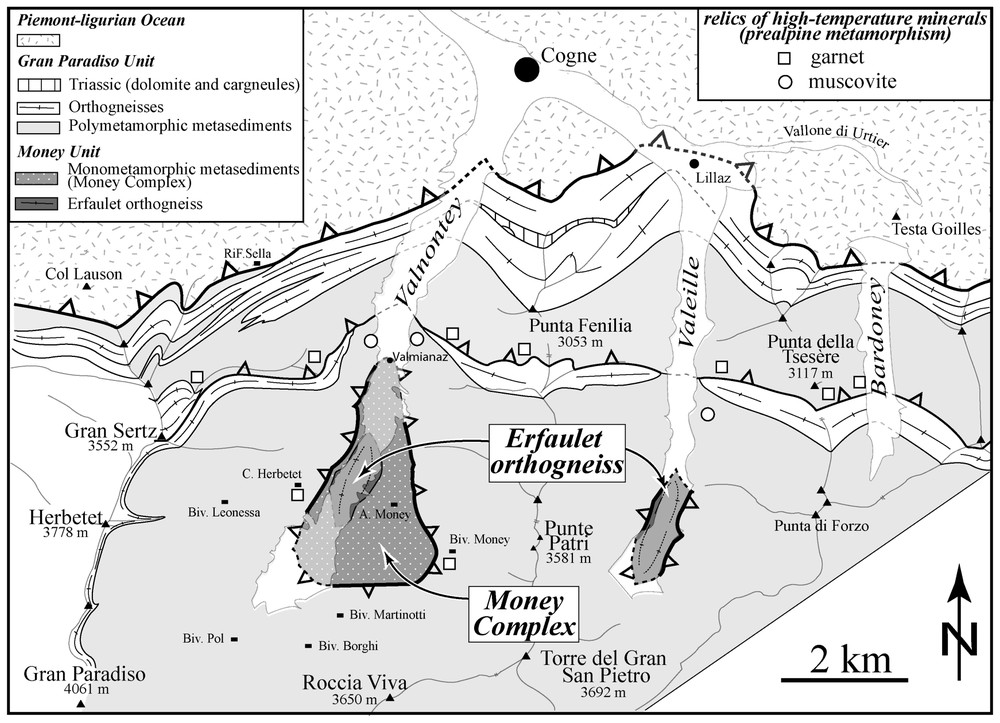

Simplified structural map of the northern part of Gran Paradiso massif (after [4,19] and work in progress). The lowest structural element, i.e. the Money Unit, comprises the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the overlying Money Complex. The latter only outcrops in the Valnontey.

Carte géologique simplifiée du Nord du massif du Grand-Paradis (d'après [4,19] et travaux en cours). L'unité du Money comprend l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet et le complexe du Money. Ce dernier affleure uniquement dans la vallée du Valnontey.

3 Données structurales

La série métasédimentaire du Money est essentiellement constituée de métaconglomérats, de micaschistes quartzeux (anciens grès) et de micaschistes graphiteux (anciennes argilites riches en matière organique). Ces alternances lithologiques permettent de définir la stratification (Fig. 3). L'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet est homogène, leucocrate, à grain fin, essentiellement constitué de quartz, d'albite, de microcline, de biotite et de rare grenat. L'analyse du contact entre l'orthogneiss et les métasédiments permet trois observations significatives.

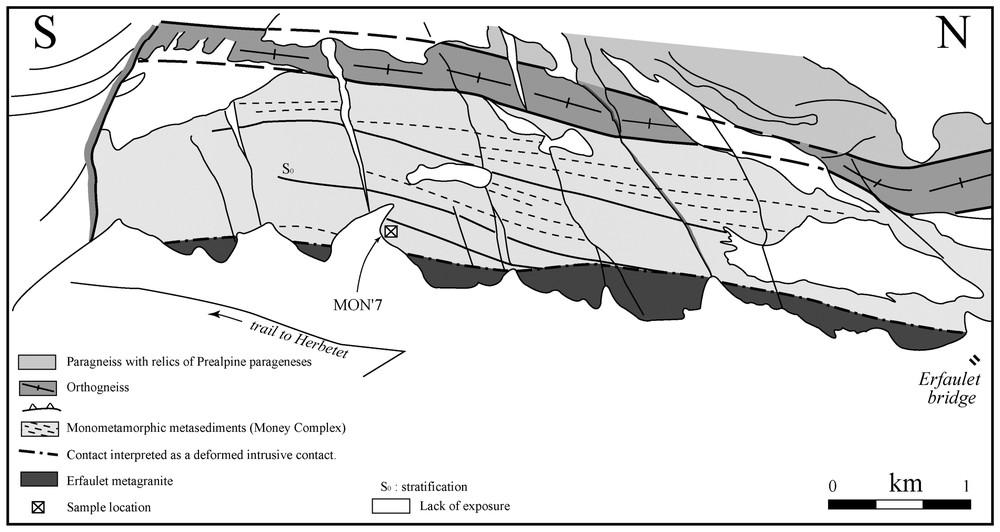

Field sketch of the contact between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the Money Complex in the Valnontey. The drawing (after photographs) represents the lowest part of the cliffs along the left bank of the Valnontey, immediately south of the Erfaulet bridge. The height of the cliff is about 300 m.

Panorama (d'après photos) représentant le contact entre l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet et le complexe du Money dans la vallée du Valnontey. Le dessin représente la partie inférieure de la falaise, le long de la rive gauche du Valnontey, au sud du pont de l'Erfaulet. La hauteur de la falaise est d'environ 300 m.

- – La stratification au sein des métasédiments du Money est oblique au contact avec l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet (Fig. 3). La bordure supérieure de l'orthogneiss est donc en contact avec différents faciès : métaconglomérats, micaschistes quartzeux et micaschistes graphiteux.

- – Des niveaux d'épaisseur décimétrique de gneiss à grain fin, leucocrates, sont localement observés au sein des métasédiments (à côté de l'échantillon MON'7, Fig. 3) et sont interprétés comme des filons aplitiques.

- – Superposées à la stratification dans les métasédiments, deux schistosités sont présentes dans toute l'unité. La première (SA1) est préservée dans les porphyroblastes d'albite ou dans des microlithons. La seconde (SA2), subhorizontale ou faiblement pentée, est associée à une linéation d'étirement est–ouest. L'étude détaillée du contact ne révèle aucune zone mylonitique (c'est-à-dire aucune augmentation de l'intensité de la déformation) en s'approchant du contact.

4 Données pétrologiques

Evolution texturale et composition chimique des minéraux. Un échantillonnage des différents faciès métasédimentaires au contact de l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet a permis la découverte de micaschistes (MON'7) (Fig. 3), dans lesquels les relations cristallisation/déformation suggèrent une histoire métamorphique polyphasée. En effet, trois épisodes de métamorphisme peuvent y être observés. Le GrtV, riche en spessartine et pauvre en grossulaire, est la seule relique (avec le quartz et la pyrite) d'un premier stade de métamorphisme (stade MV). L'assemblage GrtA (riche en grossulaire)–Phg–Ru–Ilm constitue un deuxième stade de métamorphisme (stade MA1). Enfin, la croissance de la biotite aux dépens du grenat et de la phengite, ainsi que la disparition du rutile au profit de l'ilménite, marque le troisième stade de métamorphisme, contemporain de la déformation majeure (stade MA2).

Estimation thermo-barométrique. La composition du grenat V ainsi que l'absence de rutile et/ou de phengite en inclusion dans le grenat V suggèrent que le stade MV soit un stade de métamorphisme de basse pression, et de moyenne à forte température. Le grenat A possède une teneur plus élevée en calcium et plus faible en manganèse que le grenat V. Il présente des inclusions de rutile et de phengite. Le stade MA1 est donc caractéristique d'une pression plus élevée que le stade MV. Le thermomètre grenat–phengite [22] donne, pour le stade MA1, des températures de 550 °C environ (estimées pour des pressions à 10 et 15 kbar). Le thermomètre grenat-biotite utilisant les calibrations de Williams et Grambling [32], ainsi que les thermomètres grenat-phengite et grenat-ilménite [29] indiquent des températures d'environ 450–500 °C pour le stade MA2.

5 Discussion

Différentes observations structurales nous ont amenés à mieux comprendre la nature du contact entre l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet et les métasédiments sus-jacents.

- – Aucune zone mylonitique n'est présente au contact.

- – De rares filons aplitiques ont été observés dans les métasédiments, juste au-dessus du contact avec l'orthogneiss.

- – Le contact recoupe la stratification des métasédiments sus-jacents (Fig. 3).

L'absence de mylonites exclut l'existence d'un contact tectonique. La présence de filons permet de soupçonner un contact intrusif, même si un contact stratigraphique n'est pas à exclure, puisqu'une obliquité de la stratification sur le contact pourrait s'expliquer par la présence d'un biseau stratigraphique.

Des analyses pétrologiques détaillées ont donc été réalisées afin de valider une des deux dernières hypothèses concernant la nature de ce contact. Des reliques de grenat anté-alpin ont été observées dans un micaschiste échantillonné au-dessus du contact (Fig. 4(a), (b)), ce qui suggère une histoire métamorphique polyphasée de ces métasediments. Jusqu'à maintenant, aucune relique anté-alpine (stade MV) n'avait jamais été découverte dans l'unité du Money. N'ayant subi que le métamorphisme alpin s.l (stades MA1 et MA2), cette unité est décrite comme étant monométamorphique.

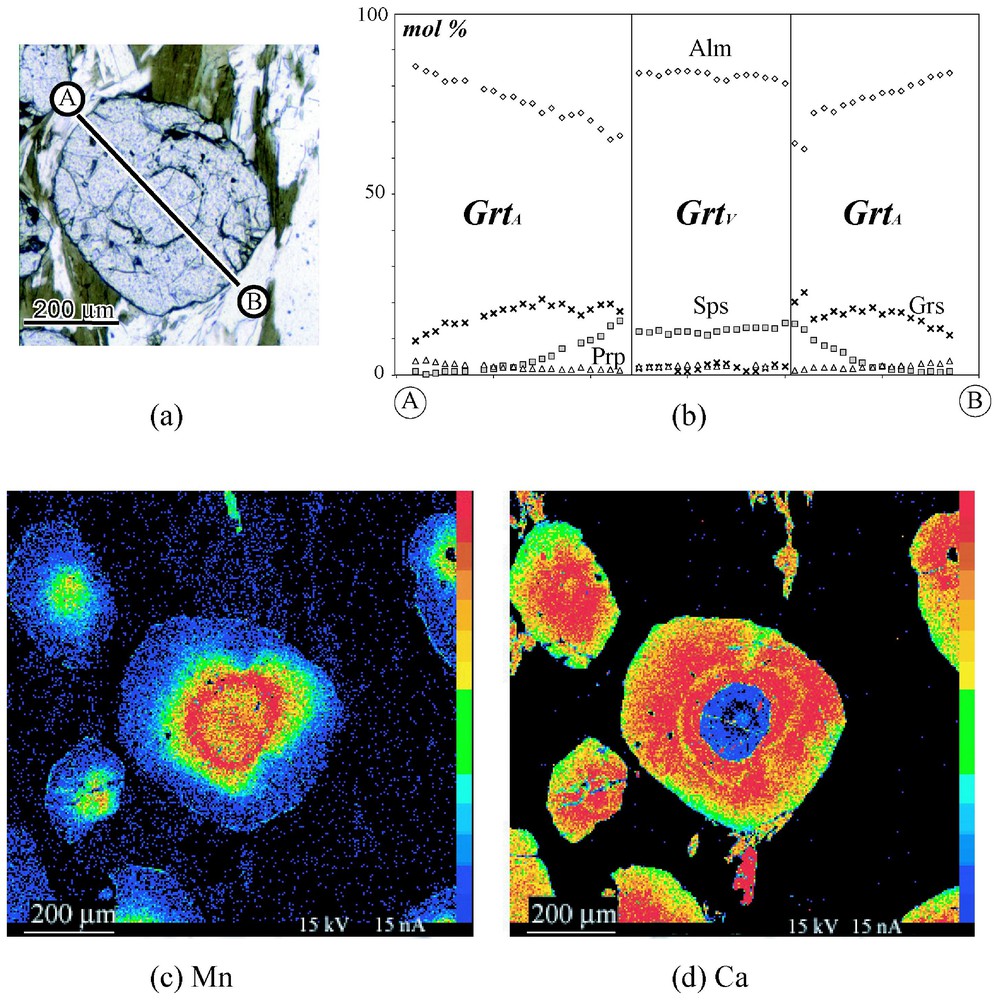

Evidence for pre-Alpine metamorphism in the Money Complex is found in sample MON'7. (a) Photomicrograph of garnet from sample MON'7. Matrix foliation is defined by phengite and biotite. Garnet displays an inner core (GrtV), separated by an optical (and chemical) discontinuity from the peripheral garnet (GrtA). (b) Electron microprobe profile of garnet, with its composition in terms of the end-members almandine (Alm), spessartine (Sps), grossular (Grs) and pyrope (Prp). GrtV is unzoned, and presents a much higher Sps content than Grs. GrtA records a growth zoning, with a strong decrease in Sps content. Note that GrtA is much more Grs-rich than GrtV, which suggests that the latter equilibrated with plagioclase. (c) and (d) X-ray element maps for Mn and Ca, respectively, in the same garnet grain, showing the coincidence of optical and chemical discontinuities.

L'échantillon MON'7 montre l'évidence d'un métamorphisme anté-alpin dans l'unité du Money. (a) Microphotographie d'un grenat de l'échantillon MON'7. La phengite et la biotite définissent la foliation matricielle. Le grenat montre un coeur (GrtV), séparé par une discontinuité optique (et chimique) d'une zone périphérique (GrtA). (b) Profil de grenat obtenu à la microsonde : almandin (Alm), spessartine (Sps), grossulaire (Grs) et pyrope (Prp). GrtV n'est pas zoné, et montre une teneur plus élevée en Sps qu'en Grs. GrtA enregistre une zonation de croissance, avec une forte diminution de la teneur en Sps. GrtA est plus riche en grossulaire que GrtV, ce qui suggère que ce dernier est équilibré avec le plagioclase. (c) et (d) Cartes d'éléments aux rayons X du Mn et du Ca, dans le même grain de grenat. Ces cartes montrent une superposition des discontinuités optique et chimique.

L'hypothèse la plus simple, rendant compte des données structurales, comme des données pétrologiques, est que ce grenat anté-alpin serait une relique de l'auréole de métamorphisme de contact, engendrée pendant l'intrusion du granite de l'Erfaulet au sein du complexe du Money.

6 Conclusion

Nous interprétons la limite entre l'orthogneiss de l'Erfaulet et les métasédiments sus-jacents comme étant initialement (avant la déformation alpine) un contact intrusif. Si nous acceptons l'âge proposé par Compagnoni et al. [19] pour les métasédiments du Money, l'intrusion du granite de l'Erfaulet pourrait avoir eu lieu, soit à la fin du Carbonifère supérieur, soit au Permien. Cette dernière hypothèse est compatible avec les données géochronologiques obtenues récemment dans les unités équivalentes des Alpes occidentales [5,11], ainsi que dans l'unité chevauchante du Grand-Paradis [6].

1 Introduction

In the western Alps, the pre-Alpine basement of the Penninic units includes two main groups of rocks [20,21,30], namely (i) more or less deformed granitoids and (ii) metasedimentary rocks. The original nature of the contacts between granitoids and metasedimentary rocks can be difficult, if not impossible, to identify. The granitoid could represent either an intrusion into the metasedimentary rocks, or the latter could have been deposited on an earlier intrusion. The contact can also correspond to a major shear zone developed during the Alpine orogeny. The aim of this work is to examine, in the Gran Paradiso massif, the contact between an orthogneiss (the Erfaulet orthogneiss) and the overlying metasediments (the Money Complex), in order to solve this question.

2 Geological setting

The Gran Paradiso massif is a large tectonic window below the eclogite-facies oceanic units derived from the Piemont-Ligurian ocean (Fig. 1). The northern part of the Gran Paradiso massif consists of two main units (Fig. 2), namely the Money Unit and the overlying Gran Paradiso Unit [4,19].

The Gran Paradiso Unit consists of abundant augen-gneisses derived from porphyritic granitoids of Late-Variscan age [13,14] and metasediments with relics of high-temperature metamorphism of pre-Alpine age. Relics of hornfelses and intrusive contacts have been found in the Orco valley [12,17], despite an eclogite-facies overprint mainly recorded in metabasites and micaschists [10,15,18,21].

The Money Unit outcrops in two windows in the northern part of the Gran Paradiso massif, and is thought to represent in the Gran Paradiso massif the equivalent of the Sanfront-Pinerolo Unit from the Dora-Maira massif [2,7,30], i.e. the lowest structural unit exposed in the internal Penninic zone. The Money Unit essentially consists of a leucocratic metagranite (Erfaulet orthogneiss), located below a thick sequence of metasandstones with conglomeratic layers [1], metasiltstones and minor metapelites, some of them being rich in graphitic layers, hence their dominant greyish–blackish colour [19]. Because the mineralogical assemblages are exclusively Alpine (i.e. because of the lack of high-temperature, hence pre-Alpine, relics in the detrital sequence), it has been argued that the Money Complex is Permo-Carboniferous in age [19]. The nature of the contact between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the overlying Money Complex has not been determined, and is the main focus of the present study. Specifically, whether the Erfaulet granite intruded the Money Complex, or whether the Money Complex unconformably overlain the Erfaulet granite, is not known. Alternatively, the two formations could eventually be separated by a tectonic contact of Alpine age.

3 Structural data

Steep cliffs on both sides of the Valnontey allow a close examination of the relationships between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the overlying Money Complex.

The Erfaulet orthogneiss (up to 50 m thick) is a medium to fine-grained, homogeneous, leucocratic body, mainly consisting of quartz, albite, microcline, biotite, muscovite and minor garnet. Deformed enclaves have not been found.

The Money Complex (up to 300 m thick) is made of a metasedimentary sequence mainly consisting of metaconglomerates, quartz-rich micaschists (former sandstone layers) and quartz-poor, graphite-bearing micaschists (former mudstones rich in organic matter). The bedding allows determination of the stratification. Graphitic layers (from a few cm up to 0.20 m in thickness) are more easily weathered than the other lithologies, and can be followed in the cliffs along the left bank of the Valnontey (Fig. 3).

A leucocratic orthogneiss (with a maximum thickness of 10–20 m) defines the upper boundary of the Money window and can be traced along both banks of the Valnontey (Fig. 3).

The three following observations are essential for understanding the meaning of the contact between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the Money Complex.

Firstly, in the metasediments of the Money Complex, the stratification is oblique to the boundary with the Erfaulet orthogneiss (Fig. 3), which can be in contact with either metaconglomerates or quartz-rich micaschists or graphitic micaschists.

Secondly, thin folded layers (0.1–0.3 m) of fine-grained leucocratic gneisses are locally observed within the metasediments close to the contact with the Erfaulet orthogneiss. Because the leucocratic gneisses intersect the sedimentary layering (e.g., close to sample MON'7, Fig. 3), they can be interpreted as former aplitic veins.

Thirdly, in the Money Complex, two foliation planes are superimposed on the sedimentary layering. An early fabric (SA1) is occasionally preserved in albite porphyroblats or as folded mica layers in microlithons. The dominant fabric (SA2) is generally subhorizontal, and bears a prominent east–west stretching lineation. A careful examination of the contact does not reveal an increasing strain towards the contact, i.e. a mylonitic zone.

4 Petrological data

4.1 Textural relationships and mineral chemistry

Previous studies on the metamorphic history of the Money Complex have emphasized its monocyclic history [19]. Our observations are fully consistent with this conclusion. Nevertheless, one sample (MON'7), a micaschist which has been taken close to the contact with the Erfaulet orthogneiss (Fig. 3), shows evidence of a polymetamorphic history. Consequently, this paper will focus on this sample.

According to textural observations, three metamorphic stages can be observed in this micaschist (Fig. 4). Most garnet grains show an inclusion-poor central part (quartz, pyrite) (GrtV), and an inclusion-rich outer part (quartz, phengite, rutile, and rare ilmenite) (GrtA). The two parts are separated by an optical discontinuity, defined by the alignment of minute quartz inclusions. Microprobe analyses reveal a major break in chemistry between the two parts of garnet. GrtV is rather homogeneous (almandine 81–88, spessartine 7–15, pyrope 2–4, grossular 1–5). A chemical discontinuity is present at the GrtV–GrtA interface, with a sudden jump in grossular content from GrtV to GrtA (from 1–2 mole% to 9–10 mole%). In addition, garnet A is zoned with an increase in FeO (XAlm=core: 60–65 mole%; rim: 77–86 mol%), and a decrease in MnO (XSps=core: 14–19 mole%; rim: 1–3 mole%), and CaO (XGrs=core: 18–23 mole%; rim: 9–17mole %) contents from core to rim.

In the matrix, no relics of the early foliation SA1 have been found. Phengite, biotite and quartz define the foliation SA2. In most cases, biotite grows in contact with garnet and phengite or along phengite rims. When in contact with garnet, biotite grains impinge within garnet rims, implying some dissolution of garnet rims. This suggests that biotite growth took place after garnet growth ceased. Rutile inclusions within garnet A have been lately replaced by ilmenite in the matrix.

Like garnet (whose composition has been discussed above), the other minerals also show chemical variations (Table 1). Phengitic substitution in white micas is highest in inclusions into GrtA and core of matrix grains (Si=6.9–6.6 pfu). Lower Si contents are found towards the rims of matrix grains (down to 6.3 Si pfu). Biotite compositions are homogeneous with an XMg value ranging from 0.24 to 0.26. The ilmenite composition is characterized by an increasing XMn value from inclusions in garnet A to matrix grains (from 0.02 to 0.05, respectively).

Representative mineral analyses from garnet, phengite, biotite and ilmenite in sample MON'7

Analyses et formules structurales représentatives des minéraux de l'échantillon MON'7 (grenat, phengite, biotite et ilménite)

| Sample MON'7 | ||||||||

| Mineral analysis N° | garnet S3-33p GrtV | garnet S3-38p GrtA-core | garnet S3-58p GrtA-rim | phengite S1-12 incl. in GrtA | phengite S1-14 matrix | biotite S1-25 matrix | ilmenite 90 incl. in GrtA | ilmenite 81 matrix |

| SiO2 | 36.79 | 36.51 | 37.01 | 51.42 | 50.05 | 34.28 | 0.77 | 0.03 |

| TiO2 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 50.56 | 52.35 |

| Al2O3 | 20.51 | 20.80 | 21.03 | 26.08 | 26.86 | 17.81 | 0.28 | 0.00 |

| Cr2O3 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| FeO∗ | 36.07 | 29.10 | 38.52 | 3.36 | 3.77 | 27.25 | 47.22 | 44.63 |

| MnO | 5.31 | 5.99 | 0.44 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 2.21 |

| MgO | 0.59 | 0.37 | 1.00 | 2.83 | 2.80 | 4.85 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| CaO | 0.75 | 6.85 | 3.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Na2O | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0 | 0.04 |

| K2O | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 11.04 | 11.31 | 9.53 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Total | 100.07 | 99.81 | 101.35 | 95.11 | 95.36 | 95.18 | 100.04 | 100.27 |

| Normalized to 24 oxygens | Normalized to 22 oxygens | Normalized to 3 oxygens | ||||||

| Si | 6.04 | 5.95 | 5.97 | 6.92 | 6.76 | 5.46 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Al | 4.01 | 3.97 | 3.97 | 3.34 | 0.01 | 0.00 | ||

| Cr | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Ti | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.96 | 0.99 |

| Fe∗ | 4.95 | 3.96 | 5.19 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 3.63 | 0.99 | 0.94 |

| Mn | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.05 | |||

| Mg | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 1.15 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Ca | 0.13 | 1.20 | 0.57 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Na | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| K | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.90 | 1.95 | 1.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 13.98 | 14.09 | 15.71 | 2.00 | 2.00 | |||

| Almandine | 0 .83 | 0 .65 | 0 .86 | |||||

| Spessartine | 0 .12 | 0 .14 | 0 .01 | |||||

| Pyrope | 0 .02 | 0 .01 | 0 .04 | |||||

| Grossulaire | 0 .02 | 0 .20 | 0 .09 | |||||

| Mg/(Mg+Fe) | 0 .03 | 0 .02 | 0 .04 | 0 .60 | 0 .57 | 0 .24 | ||

| Mn/(Mn+Mg+Fe) | 0 .02 | 0 .05 |

∗ All Fe is assumed to be divalent.

To sum up (Fig. 4), garnet V is the only relic (with quartz and pyrite) of a first metamorphic stage (stage MV). The assemblage made up of garnet A, phengite, rutile, ilmenite and quartz belongs to a second metamorphic stage (stage MA1). Lastly, replacement of garnet and phengite by biotite, and rutile breakdown defines a third metamorphic stage (stage MA2).

4.2 P–T conditions

Estimating P–T conditions for stage MV relies on the presence of garnet and the lack of rutile and phengite in inclusion. The chemistry of garnet V is characterized by a very-low grossular content and a high spessartine content, a feature repeatedly observed for similar bulk-rock chemistries both in contact metamorphic aureoles [25] and in low-pressure, regional metamorphic terranes, e.g., [3,16,23,28]. This suggests that stage MV occurred during a low pressure, medium- to high-temperature metamorphism.

Garnet A, with a higher calcium content compared to garnet V, and a decreasing manganese content from the inner to the outer part, contains phengite and rutile inclusions. This assemblage is characteristic of a high-pressure metamorphism. In metamorphic stage MA1, temperatures are estimated to be around 550 °C (pressure at 10 and 15 kbar), using the FeMg−1 partitioning between garnet and phengite [22,24]. No precise estimate of the pressure can be obtained in the studied sample, because of the lack of a buffering assemblage similar to those used in the experimental studies. The Si content of phengite cores (about 6.90 pfu) can thus only be used for estimating minimum values of the pressure, of the order of 12 kbar [27].

Stage MA2 is mainly characterized by the growth of biotite and ilmenite at the expense of garnet, phengite and rutile. Geothermometers based either on the FeMg−1 partitioning between garnet and biotite [32], garnet and phengite [22,24], or on the FeMn−1 partitioning between garnet and ilmenite [29], indicate temperatures at around 450–500 °C for metamorphic stage MA2.

Similar patterns of garnet zoning have been recorded in a number of metamorphic terranes, not only in the Western Alps [2,8,31], but also in other collision zones [26]. All authors agree on their interpretation as recording two distinct events, an earlier low-pressure event followed by a new growth stage at high pressure. The early event could result from a regional-scale metamorphism, or from a contact metamorphism.

5 Discussion

In a pre-Alpine basement, three kinds of contacts (stratigraphic, intrusive or tectonic) between metagranitoids and metasedimentary rocks are possible. New structural data brought us a better understanding of the nature of the contact between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the overlying metasediments: (i) a mylonitic zone is not present at the contact; (ii) rare aplitic dykes have been found in the metasediments, close to the contact with the orthogneiss; (iii) the boundary is oblique to the bedding in the overlying metasediments (Fig. 3). Thus, structural data are compatible with an intrusive contact (aplitic dykes, lack of mylonites) rather than an unconformity at the base of the Money Complex. Petrological data allow identification of pre-Alpine relics (stage MV) that have survived the Alpine cycle (stages MA1 and MA2) in the Money Complex. Witnesses of the low-pressure (stage MV) metamorphism have been found in only one sample, where they are mainly recorded by garnet cores (GrtV).

Consequently, two hypotheses are to be envisaged for integrating structural and petrological data. Firstly, the Money Complex could be a polycyclic unit rather than a monocyclic unit as previously accepted [19]. Secondly, the pre-Alpine relics would be due to a contact metamorphism associated with the intrusion of the Erfaulet granite into the Money Complex. We favour the second hypothesis because it makes petrological data (pre-Alpine relics only observed close to the contact with the Erfaulet orthogneiss) consistent with the structural data (lack of mylonites, aplitic dykes in the Money Complex, and crosscutting relationships with respect to the sedimentary layering).

6 Conclusion

We interpret the boundary between the Erfaulet orthogneiss and the overlying metasediments as being (before the Alpine deformation) an intrusive contact. Most authors assume that the Money metasediments were deposited during the Upper Carboniferous [19]. Recent re-examination of the palaeontological data from the Zone Houillère in the Briançonnais Zone (i.e. the unmetamorphosed equivalent of the Money Complex) suggests a Namurian B-C to Westphalian A age for deposition of the graphitic and conglomeratic sediments [9]. Consequently, the intrusion of the Erfaulet granite would have taken place either during the Upper Carboniferous or during the Permian. Such an assumption is compatible with recent geochronological data obtained for: (i) granitoids intruding the Zone Houillère in the Aosta valley (Costa Citrin: about 320–325 Ma [5]); (ii) metagranitoids in the Sanfront-Pinerolo Unit (from about 300 to 270 Ma [11]); and (iii) metagranitoids in the overthrusting Gran Paradiso Unit (about 270 Ma [6]).

Acknowledgments

The Ente Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso is thanked for allowing field work and rock sampling in the Valnontey. J.-M. Bertrand and P. Tricart helped improve the content of this article.