Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

Les phénomènes d'ébullition ou de mélange sont considérés comme les principaux processus minéralisateurs dans les gisements épithermaux de type low-sulphidation [19]. Cette constatation résulte d'observations directes dans les systèmes géothermique actuels [31], de la connaissance géochimique des complexes métalliques associés à ces dépôts [27,28], ainsi que de modélisations numériques de ces processus minéralisateurs [12,25,32]. Pour documenter la compréhension de ces processus minéralisateurs, une étude couplée de la minéralogie, des inclusions fluides ainsi que des isotopes de l'oxygène a été menée sur le gisement de Sando Alcalde situé dans le Sud-Ouest du Pérou.

2 Contexte géologique

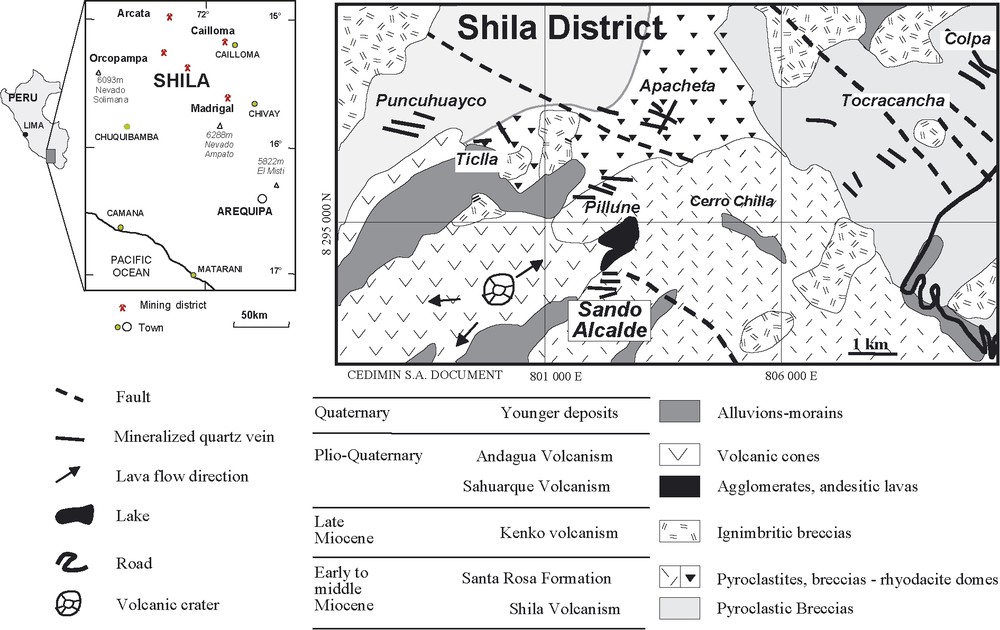

Le système de veines minéralisées de Sando Alcalde fait partie du district de Shila (Fig. 1). Cette région est constituée d'un soubassement de roches sédimentaires, intrudé par des unités complexes de roches volcaniques d'âge Néogène (Fig. 1). Différents gisements d'or et d'argent sont localisés dans les roches volcaniques calco-alcalines d'âge Miocène inférieur à moyen. Des données de terrain montrent que la majorité des corps minéralisés est constituée d'une association entre une veine principale d'orientation est–ouest et des veines secondaires orientées N120–135°E [7–9].

Geological map of the Shila district. The location of the main deposits of the district is indicated (modified from a CEDIMIN SA document).

Carte géologique du district de Shila. Les principaux gisements constituant ce district sont indiqués (modifié d'après un document Cedimin SA).

3 Minéralogie

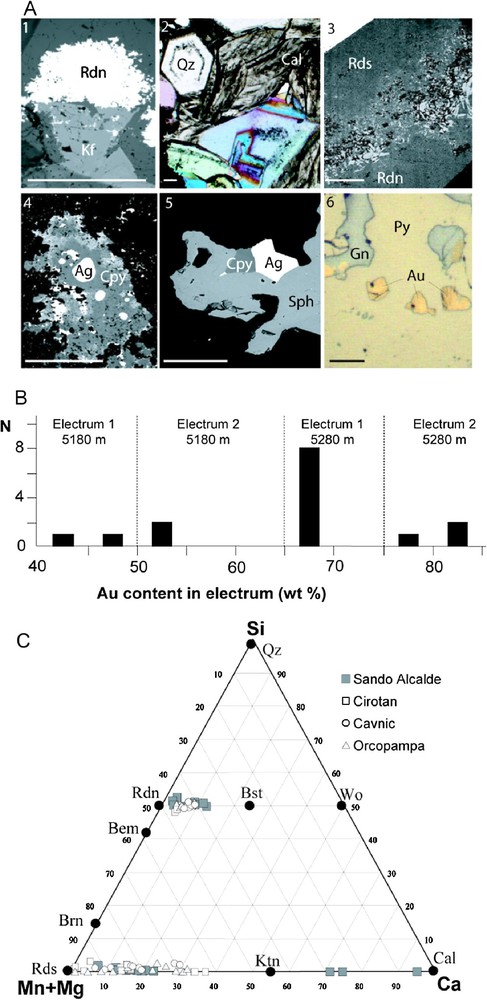

Deux principaux stades de dépôts sont observés. Le premier consiste en un assemblage complexe de quartz, adulaire, pyrite, galène, sphalérite, chalcopyrite, électrum et silicates de manganèse remplissant les veines principales. Le second stade porte l'essentiel de la minéralisation précieuse, avec un assemblage complexe de quartz, sphalérite, chalcopyrite, pyrite, adulaire, galène, tennantite–tetraédrite, polybasite–pearcéite et électrum (Fig. 2). La teneur en Au de l'électrum varie du stade 1 au stade 2, ainsi qu'en fonction de l'altitude de l'échantillon (Fig. 2B). Dans la gangue, les minéraux de manganèse, carbonates et silicates sont abondants (Fig. 2C) et présentent une composition similaire à ceux d'autres gisements épithermaux, Orcopampa (Pérou), Cirotan (Indonésie) et Cavnic (Roumanie) [20,22] (Fig. 2B). De l'adulaire rhombique à aciculaire est observée en association avec la calcite lamellaire (Fig. 2A).

(A) Photomicrographs showing the vein mineralogy of the Sando Alcalde deposit with typical gangue (1 to 3) and ore mineral (4 to 6) assemblages. Microphotographs Nos. 2 and 6 were taken in reflected light, whereas the others result from SEM backscatter analyses. Scale bar is 100 μm. (B) Distribution of Au content in electrum of the stage 1 (electrum 1) and the stage 2 (electrum 2) considering the elevation of samples (5180 and 5280 m). (C) Composition of the silicates and carbonates of manganese constituting the gangue minerals of Sando Alcalde (grey squares). These compositions have been compared with those of Cirotan (Indonesia, white squares), Cavnic (Romania, white circles), and Orcopampa (Peru, white triangles) deposits [20,22]. Qz = quartz, Rdn = rhodonite (Mn[SiO3]), Prx = pyroxmangite, Bem = bementite, Rds = rhodocrosite (Mn[CO3]2), Ktn = kutnahorite (CaMn[CO3]2), Cal = calcite, Wo = wollastonite (CaSiO3), Bst = bustamite (CaMn[SiO3]2), Kf = adularia, Ag = argentite, Cpy = chalcopyrite, Gn = galena, Py = pyrite and Au = gold. Masquer

(A) Photomicrographs showing the vein mineralogy of the Sando Alcalde deposit with typical gangue (1 to 3) and ore mineral (4 to 6) assemblages. Microphotographs Nos. 2 and 6 were taken in reflected light, whereas the others result from SEM ... Lire la suite

(A) Photographies des veines minéralisées du gisement de Sando Alcalde avec des assemblages minéralogiques typiques de la gangue (1 à 3) et du minerai (4 à 6). Les photographies 2 et 6 ont été prises en lumière réfléchie, alors que les autres résultent d'analyses au microscope électronique à balayage. La barre d'échelle représente 100 μm. (B) Teneur en Au de l'électrum observé dans les stades 1 (électrum 1) et 2 (électrum 2) en fonction de leur altitude (5180 et 5280 m). (C) Composition des carbonates et silicate de manganèse qui constituent les minéraux de gangue (carrés gris). Ces compositions ont été comparées avec celles des gisements de Cirotan (Indonésie, carrés blancs), Cavnic (Roumanie, cercles blancs) et Orcopampa (Pérou, triangles blancs) [20,22]. Masquer

(A) Photographies des veines minéralisées du gisement de Sando Alcalde avec des assemblages minéralogiques typiques de la gangue (1 à 3) et du minerai (4 à 6). Les photographies 2 et 6 ont été prises en lumière réfléchie, alors que ... Lire la suite

4 Caractéristiques physico-chimiques des fluides minéralisateurs

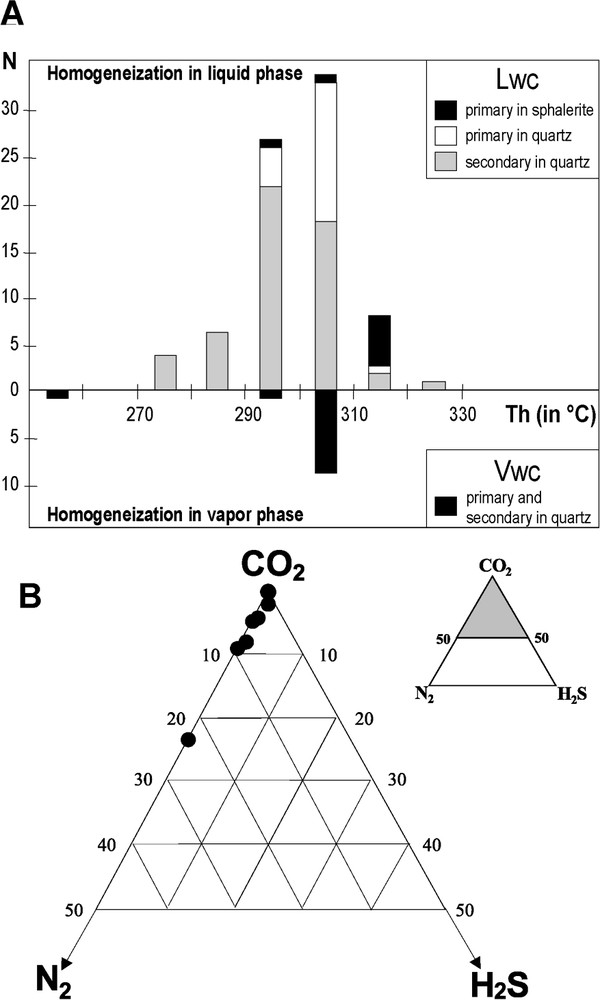

Des études microthermométriques et par spectrométrie Raman ont été réalisées sur les inclusions fluides associées à la minéralisation. Deux types d'inclusion ont été observés : des inclusions aquo-carboniques à phase liquide dominante (Lw-c) et des inclusions aquo-carboniques à phase vapeur dominante (Vw-c). Le détail des analyses microthermométriques est présenté dans le Tableau 1. La Fig. 3A montre une répartition statistique des températures d'homogénéisation de ces deux types d'inclusion. Les deux types d'inclusion s'homogénéisent dans la même gamme de température autour de 300 °C, qui est ainsi considérée comme la température de piégeage de ce fluide en ébullition, même si quelques rares valeurs sont observées en dessous.

Microthermometric data. Abbreviations for the different microthermometric parameters are defined in the text. (n)=number of measurements

Données microthermométriques. Les abréviations des différents paramètres microthermométriques sont indiquées dans le texte. (n)=nombre de mesures

| Inclusion type | Host mineral | Mineralization stage | Type |

|

|

Salinity in wt % NaCl |

|

|

|

| Lw-c | sphalerite | 1 | primary | −2.5 to −4.8 (10) | 285 to 315 (8) | 4.2 to 7.6 | |||

| quartz calcite | 1 and 2 | primary | −3.1 to −6.5 (24) | 305 to 321 (20) | 5.1 to 9.9 | ||||

| 1 and 2 | secondary | −0.1 to −1.7 (63) | 278 to 325 (50) | 0.2 to 2.9 | |||||

| Vw-c | Qz | 1 and 2 | primary and secondary | – | 250 to 300 (10) | – | −58.0 to −59.5 (8) | −4.3 to +2.6 (8) | −1.3 to +7.0 (14) |

(A) Distribution of the homogenization temperatures (

(A) Distribution des températures d'homogénéisation des différents types de fluides rencontrés. (B) Diagramme ternaire CO2–H2S–N2 montrant la composition de la phase gazeuse des inclusions fluides de type Vw-c. Voir texte pour les détails.

5 Les isotopes de l'oxygène

Des analyses isotopiques de

δ18O isotopic data. The last column indicates the calculated δ18O values for related hydrothermal fluids using the fractionation equation for isotopic compounds of oxygen [23]

Données isotopiques δ18O. La dernière colonne indique les valeurs calculées pour le fluide hydrothermal [23]

| Sample name | Height | Mineral |

|

|

| SHS PE62a | 5180 m | adularia | +3.1 | −1.7 |

| quartz | +3.5 | −3.4 | ||

| SHS PE61f | 5230 m | adularia | +3.9 | −0.9 |

| quartz | +5.0 | −1.9 | ||

| SHS PE58e | 5280 m | adularia | +6.3 | +1.5 |

| quartz | +5.7 | −1.2 | ||

| SHS PE59a | 5330 m | adularia | +5.2 | +0.4 |

| quartz | +5.5 | −1.4 |

6 Discussion sur les processus minéralisateurs

6.1 Évidence d'un processus d'ébullition

Un processus d'ébullition semble exercer un contrôle majeur sur le dépôt de la minéralisation. Du point de vue des fluides, la présence de plans d'inclusions vapeur possédant le même rapport liquide/vapeur et de tailles similaires est également un fort indicateur d'ébullition, car un tel remplissage ne peut être lié à des phénomènes d'étranglement [4]. L'homogénéisation des deux types de fluides (l'un à phase vapeur dominante, l'autre à phase liquide dominante) dans la même gamme de température fournit également un argument en faveur de l'hypothèse selon laquelle ces deux fluides résultent du piégeage synchrone de deux phases immiscibles résultant d'un phénomène d'ébullition. D'un point de vue minéralogique, la présence de calcite lamellaire ainsi que celle d'adulaire rhombique sont de forts indicateurs d'un phénomène d'ébullition [11,21,30].

7 Les contraintes isotopiques

En l'absence de données isotopiques et sans connaissance de la composition isotopique des eaux météoriques de cette région à cette époque, deux hypothèses peuvent expliquer la composition intermédiaire des fluides hydrothermaux entre des eaux météoriques et magmatiques : un mélange entre eaux météoriques et eaux magmatiques et/ou un équilibrage des eaux météoriques avec les roches volcaniques encaissantes [14,18,29].

Les données isotopiques de l'oxygène montrent une corrélation entre l'altitude et les valeurs de

8 Conclusion

À Sando Alcalde, les données minéralogiques des inclusions fluides et des isotopes de l'oxygène témoignent qu'un processus d'ébullition est responsable du dépôt de la minéralisation précieuse. Cela corrobore les études réalisées dans ce secteur sur les gisements de même type d'Arcata, Orcopampa et Apacheta [1,2,6,15,20].

1 Introduction

Boiling and mixing appear as the most efficient of many processes that can lead to the deposition of ore- and gangue minerals in a low-sulphidation-type epithermal system [19]. They effectively control compositional changes like pH and mineral solubilities in hydrothermal fluids, thus constraining mineral deposition. This assumption is corroborated by direct observations of geothermal fields [31], geochemistry of metal complexes [27,28] and numerical modelling [12,25,32]. Simple cooling of hydrothermal fluids [12], or dilution by cold groundwater [17,32], or interaction with surrounding wall rock [32] seems to be of less importance in governing ore deposition in such an environment.

A mineralogical, fluid inclusion and stable isotopic study was carried out on the Sando Alcalde vein system, part of the Shila district (southwestern Peru), to document and discuss the mechanisms responsible for the ore deposition in a case-study of an Andean low-sulphidation deposit.

2 Geological framework

The Sando Alcalde vein system is a part of the Shila district hosted by Neogene volcanic rocks (Fig. 1). The area is underlain by a folded sedimentary basement and overlain or intruded by a complex unit of Neogene volcanic rocks. Precious-metal ores are found within Early to Middle Miocene calc-alkaline volcanic rocks that include lava flows and volcanic breccias. The Shila district includes the Apacheta, Pillune, Sando Alcalde, Puncuhuayco, Ticlla, Tocracancha, and Colpa deposits, each consisting of several mineralized veins (Fig. 1). Mining of the Shila veins began in 1990 by the CEDIMIN SA Company. Until 1997, the mine produced more than 400 000 tons of ore, with ca. 10 g/t of gold and ca. 260 g/t of silver from Apacheta, Pillune and Sando Alcalde veins. Field observations have shown that most of the mineralized bodies consist of the systematic association of a main east–west vein and secondary N120–135°E veins, formed during strike-slip tectonics [7–9].

3 Mineralogy

Two main stages of ore deposition have been identified. Stage 1 consists of an assemblage of quartz, adularia, pyrite, galena, sphalerite, chalcopyrite, electrum, Mn-silicates and Mn-carbonates filling the main east–west-trending veins. Stage 2 carries most of the precious mineralization. It consists of quartz, Fe-poor sphalerite, chalcopyrite, pyrite, adularia, galena, tennantite–tetrahedrite, polybasite–pearceite and electrum (Fig. 2A). The distribution of Au content in electrum increases from stage 1 to stage 2 and according to the elevation of samples (Fig. 2B).

The gangue is composed of euhedral quartz crystals, abundant Mn-bearing silicates and Mn-carbonates (Fig. 2). The composition of silicates lies along the rhodonite (MnSiO3)–bustamite (CaMnSiO3) tie line, whereas the composition of carbonates evolves from rhodocrosite to manganiferous calcite, the later often occurring as platy crystals (Fig. 2B). Similar mineralogical compositions were observed in the epithermal low-sulphidation deposits of Orcopampa (Peru), Cavnic (Romania) and Cirotan (Indonesia) (Fig. 2B) [20,22]. Adularia, having a rhombic morphology type [11], is also observed in ore veins.

4 Physicochemical characteristics of the ore fluids

The fluid inclusion microthermometric studies were carried out by using a Chaixmeca heating-freezing stage [24]. Salinity, expressed in wt.% NaCl, was calculated from microthermometric data using equations from Bodnar [3]. The presence and molar fraction of gas (CO2, H2S, N2) were determined in individual fluid inclusions by Raman spectroscopy [13].

4.1 Petrography of fluid inclusions

The fluid inclusions are either primary or secondary in origin, using the criteria of Roedder [26] and Bodnar et al. [4]. Two types have been identified and include, according to Boiron et al. [5]:

- – aqueous-carbonic liquid-rich inclusions (Lw-c), commonly with 10 to 30 estimated vol.% vapour, are observed as primary inclusions in sphalerite (stage 1) or as secondary inclusions in quartz (stages 1 and 2) and calcite (stage 1). Their size ranges from 3 to 120 μm with a majority between 10 and 20 μm;

- – aqueous-carbonic vapour-rich (Vw-c) inclusions, with more than 90 estimated vol.% vapour, occur as primary and mainly as secondary inclusions in quartz (stages 1 and 2). Their size is constant, between 3 to 30 μm.

4.2 Microthermometric and Raman results

Results of the microthermometric and Raman studies are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

4.2.1 The aqueous-carbonic liquid-rich fluids (Lw-c)

In sphalerite (stage 1), primary inclusions present ice-melting temperatures

4.2.2 Aqueous-carbonic vapour-rich fluids (Vw-c)

Freezing and heating experiments were restricted to the largest inclusions with good optical properties because of the small volume of the liquid phase. The Vw-c inclusions show

5 Stable isotopic data

Stable isotopic oxygen (δ18O) data have been obtained on gangue minerals of stage 1 (adularia and quartz) at different levels in the deposit (from 5180 m to 5330-m height). Oxygen was extracted from quartz and adularia and analysed with the method of Clayton and Mayeda [10]. Results are presented in Table 2. The δ18O values are comprised between 3.1‰ and 6.3‰ for adularia and 3.5‰ and 5.7‰ for quartz. The quartz–adularia oxygen fractionation varies between −0.6 to

6 Constraints on ore deposition

6.1 Boiling evidence

Boiling appears to exert a major control on the location of ore. The presence of many fluid-inclusion planes (secondary inclusions) containing only Vw-c inclusions with similar size and liquid/vapour ratio is a strong indicator of boiling as such filling cannot be linked to necking-down phenomena [4]. Moreover, the Lw-c fluid (liquid dominant) and the Vw-c fluid (vapour dominant) have a similar range of homogenization temperature around 300 °C (Fig. 3A). The trapping temperature condition of this boiling fluid should thus be this 300 °C value even if lower values have been observed in some rare fluid inclusions. The coexistence of liquid-rich (Lw-c) and vapour-rich (Vw-c) primary and secondary inclusions in quartz from stage 1 and 2 suggests that boiling is not restricted to one stage, but occurs repeatedly during vein formation.

Presence of platy calcite and rhombic adularia is a strong mineralogical indicator of boiling [11,12,21,30]. The release of CO2 to the vapour phase during boiling leads to a pH increase in the solution, causing a shift from the illite stability domain to that of adularia, and the precipitation of calcite and adularia [30]. For Dong and Morrison, rhombic adularia might also be formed under rapidly changing conditions implying rapid crystallization conditions at low temperature and this most likely happens when violent boiling is further protracted.

6.2 Stable isotopic constraints

Isotopic oxygen values obtained on quartz and adularia minerals and estimated oxygen values deduced for the ore fluids are similar to those described for this type of deposit in such a volcanic environment [14]. In lack of hydrogen isotopes values and without the knowledge of isotopic meteoric water in this region at this time, two assumptions can be made to explain the isotopic compositions of estimated ore fluids: a mixing between meteoric and magmatic water and/or an equilibration of meteoric water with surrounding volcanic altered rocks [14,18,29].

The oxygen isotope data show correlations between sample elevation and δ18Oquartz values. Samples from the lowest elevations (5180 m) have the lightest δ18O

7 Conclusion

At Sando Alcalde, mineralogy, fluid inclusion data and isotopic values give strong arguments for a boiling phenomenon instead of fluid mixing for the ore formation. This conclusion corroborates fluid inclusion studies previously performed in this area, on the low-sulphidation epithermal deposits of Arcata [6], Orcopampa [15,20] and Apacheta [1,2], where boiling is described as the main fluid process for ore deposition.

Acknowledgments

This work has been carried out within the framework of the French Metallogeny research program (GdR Métallogénie and Transmet, gold theme). Two anonymous reviewers are sincerely thanked for their constructive comments. Thanks are due to Cedimin SA for its financial and field support and T. Lhomme for the Raman spectroscopy analyses.