Version française abrégée

1 Introduction

L'intensification des cultures de coton depuis 1960 entraîne et accélère l'assèchement de la mer d'Aral, et provoque une chute de son niveau de 25 m et une augmentation de la salinité de 10 à 40 g l−1, entre 1960 et 1998 [22]. Les seuls apports d'eaux douces proviennent de l'Amu Daria et du Syr Daria, qui prennent leur source dans les montagnes du Pamir et du Tien Chan (Fig. 1) [8,10]. L'histoire sédimentaire de la mer d'Aral est jalonnée par plusieurs épisodes transgressifs et régressifs [1,3,14,16,25,38] ; les hauts niveaux sont marqués par des accumulations de silts, les bas niveaux par des carbonates. Le forage analysé (carotte 48) a été effectué dans la partie centrale du bassin, sous une profondeur d'eau de 25 m. De 4 m de longueur, il a recoupé les alternances les plus récentes (jusqu'à 9000 ans BP). La minéralogie et la géochimie ont été analysées dans les niveaux carbonatés et ont permis ainsi de déterminer les caractères de la sédimentation en période de bas niveau de la mer d'Aral. La carotte étudiée est proche des forages 15 et 86 (Fig. 2), dont les niveaux régressifs ont fait par ailleurs l'objet de datations 14C [9,24,25], ce qui a permis, par assimilation aux horizons carbonatés, de dater les niveaux de la carotte 48 (Fig. 3).

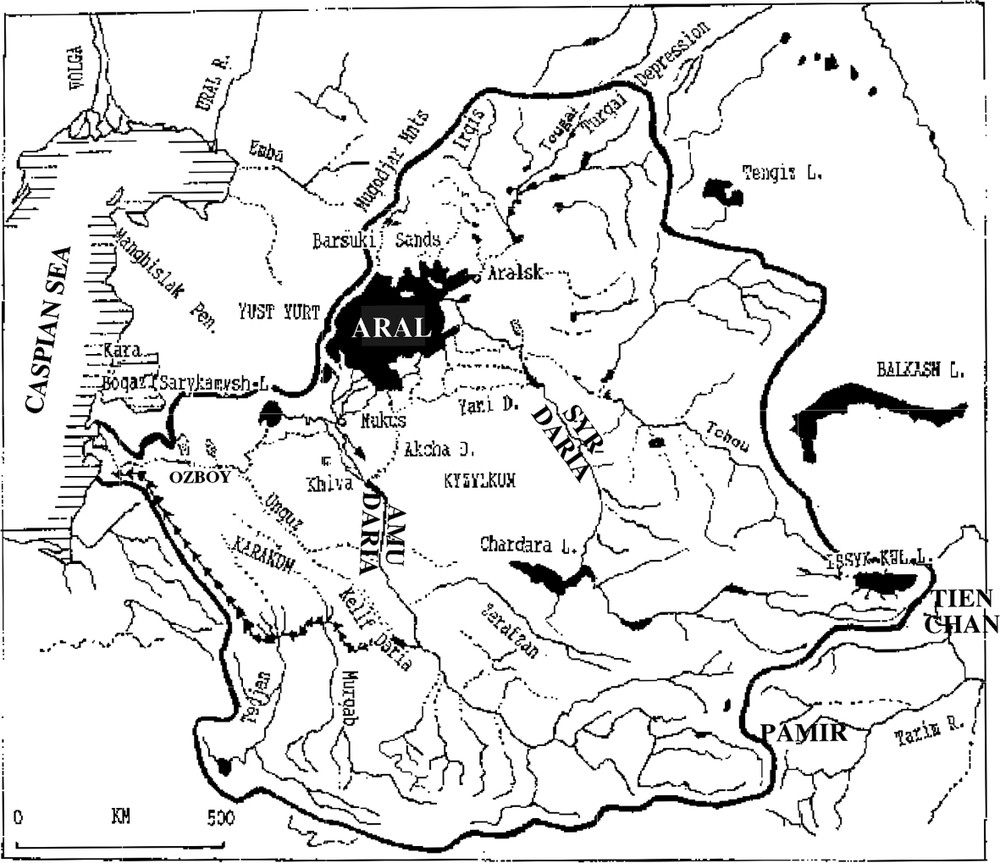

Geographical map and catchment area of the Aral Sea [20]. Dotted lines: palaeochannels; arrowed line: the Great Turkmenian canal; bold line: catchment area limit.

Carte géographique et étendue du bassin d'alimentation de la mer d'Aral [20]. Les lignes en pointillés représentent les paléochenaux, les flèches le grand canal de Turkménie et la ligne en trait gras les limites du bassin versant.

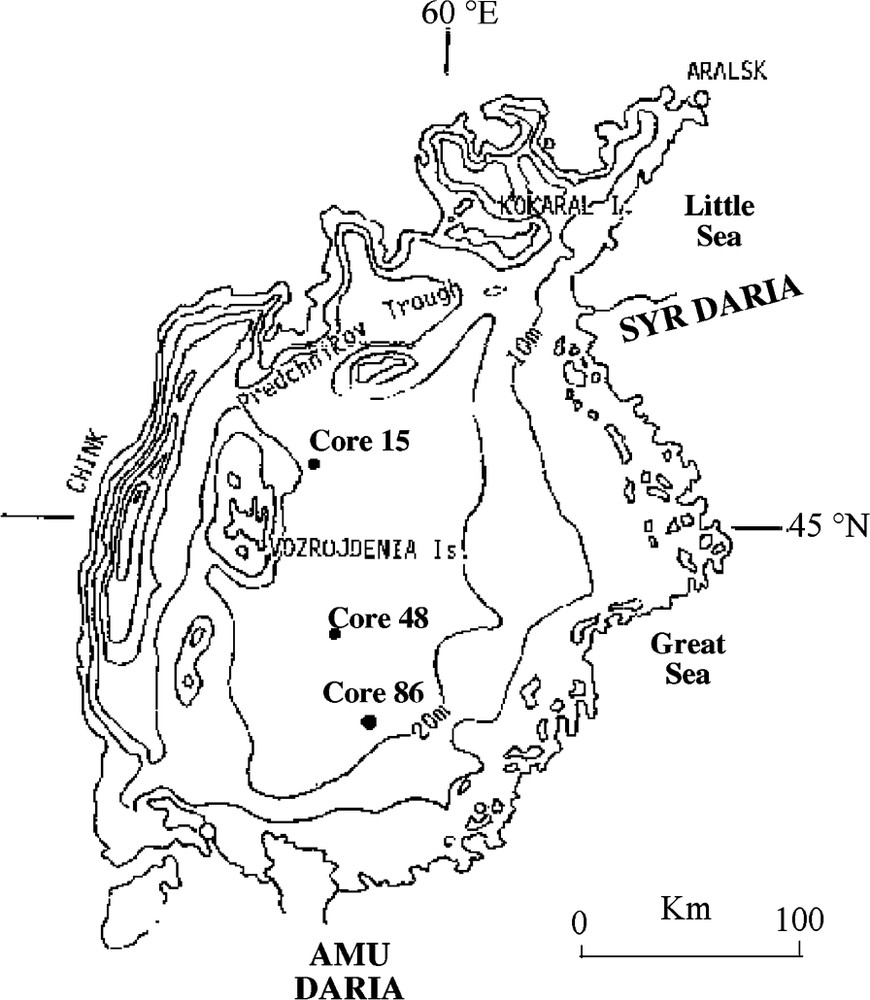

Bathymetric map of the Aral sea (1955 isobaths) and localization of cores 15, 86 and of the studied core 48 (from [21]).

Carte bathymétrique de la mer d'Aral (isobathes de 1955) et localisation des carottes 15, 86 et du sondage étudié 48 (d'après [21]).

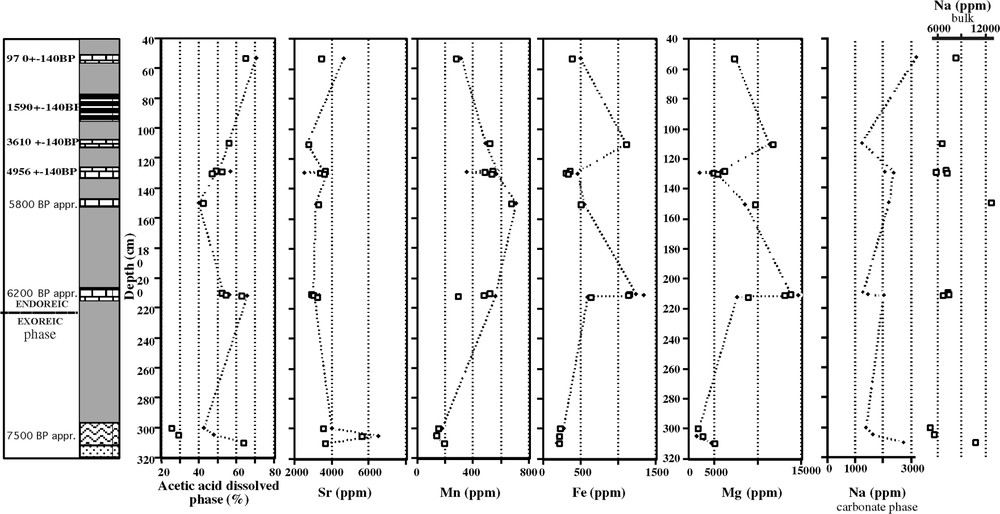

Sedimentologic correlations between dated cores 86 and 15 and the studied section 48. Time scale is based on absolute 14C dates [9,24,25] and approximate dates are estimated from the sedimentary rate and sedimentologic correlations (from [21]).

Corrélations sédimentologiques entre les sondages 86 et 15 qui ont été datés et la carotte étudiée 48. L'échelle des temps est basée sur des datations 14C [9,24,25]. Les âges approximatifs sont déterminés à partir d'un taux de sédimentation moyen et des corrélations lithologiques (from [21]).

2 Résultats et discussion

L'association minéralogique des horizons carbonatés se compose de carbonate de calcium (calcite, calcite faiblement magnésienne et aragonite), de gypse et d'une fraction détritique (quartz, kaolinite et smectite, Tableau 1). Dans certains dépôts carbonatés (échantillons prélevés à 305, 300, 129/128 cm, Fig. 3), le gypse est plus ou moins abondant. La calcite magnésienne est observée dans les sédiments lorsque le gypse est rare (Tableau 1).

Semi-quantitative estimation of carbonate and detritic minerals abundance from the X-ray diffraction analysis

Estimation semi-quantitative de l'abondance des minéraux carbonatés et détritiques à partir des analyses par diffraction des rayons X

| Depth from the top of the core (cm) | Gypsum | Low-Mg calcite | Slightly manganiferous calcite | Aragonite | Quartz | Kaolinite | Smectite |

| 53 | trace | ++++ | +++ | + | ++ | + | ++ |

| 110 | + | ++++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | |

| 128 | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | |

| 129 | ++ | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ | +++ | |

| 150 | + | ++++ | ++ | ++ | |||

| 211 | + | ++ | +++ | + | ++ | trace | |

| 212 | + | ++ | ++ | + | +++ | + | |

| 300 | very high | + | ++ | ||||

| 305 | very high | ||||||

| 310 | + | + | ++++ | ||||

| Sand | ++ | + | very high |

La teneur en chlorures relativement élevée des eaux de la mer d'Aral peut altérer le signal géochimique originel par leur mise en solution, en même temps que la fraction carbonatée lors de l'attaque ménagée à l'acide acétique. Après le broyage des échantillons, une fraction a subi un traitement préalable : plusieurs rinçages à l'eau distillée chaude (90 °C). Le lessivage des chlorures est établi par la mesure de la conductivité des eaux de rinçages. Les deux fractions (lavée et non lavée) sont ensuite mises en solution. Les teneurs en Sr, Mn, Fe et Mg présents dans la phase minérale solubilisée reflètent essentiellement celles de la phase carbonatée, tandis qu'une partie du sodium provient du lessivage des chlorures riches en Na (Fig. 4). Malgré le petit nombre de niveaux échantillonnés, le diagramme SrMg montre deux nuages de points (Fig. 5). Une corrélation négative caractérise un premier ensemble, les sédiments riches en Sr sont pauvres en Mg. Un contrôle minéralogique explique cette observation, étant donné que les échantillons de ce groupe renferment de la calcite et de l'aragonite, dont le coefficient d'incorporation du Sr est relativement élevé [31]. Le diagramme NaSr fait également ressortir les mêmes nuages de points (Fig. 5). En domaine intracontinental, il existe une corrélation positive forte entre les teneurs en Na et Sr dans les carbonates et la salinité des eaux du milieu de précipitation [30,39,40]. Cette corrélation observée dans le diagramme NaSr marque ainsi un contrôle par la salinité des eaux du bassin. Le diagramme MnFe montre aussi les deux mêmes ensembles de points. Dans le premier, une relation positive nette existe entre les deux éléments ; le second est caractérisé par de fortes teneurs en Mn et Fe. La teneur en ces deux éléments dans les carbonates est contrôlée par des variations, soit des apports issus de l'altération chimique au niveau du bassin drainant, soit des conditions d'oxygénation du milieu. Des conditions réductrices favorisent la stabilité en solution de Mn et de Fe. Mais le peu d'indices sédimentologiques et les très faibles teneurs en sulfates [17,32] ne permettent pas de mettre en évidence des changements significatifs des conditions rédox dans les dépôts, ce qui permet d'exclure ce contrôle. En revanche, en supposant que la composition chimique des eaux de chacun des deux tributaires est restée relativement constante durant l'Holocène [20], l'analyse chimique des échantillons permet de déduire que le bassin dans lequel les sédiments se sont accumulés est caractérisé par des apports fluviaux variables. Durant la période considérée, le Syr Daria s'est toujours déversé dans la mer d'Aral, alors que l'Amou Daria a pu être détourné vers la mer Caspienne [4,5,15,19,23]. Lors de périodes régressives, le volume d'eau du fleuve Syr Daria était parfois plus abondant que l'autre [15,20,21]. Lorsque les apports du Syr Daria prédominent, la fraction carbonatée des sédiments est pauvre en Fe (apports négligeables sous forme dissoute et particulaire) et riche en sulfates divers (apports d'environ

Percentage of mineral soluble phase in acetic acid, trace elements contents in the carbonate sediments from core 48 (Aral Sea). Lozenges: washed sample; square: no preliminary treatment. Dating by correlation with the cores 86 and 15 (Fig. 3).

Évolution du pourcentage de la fraction minéral soluble dans l'acide acétique et des teneurs en éléments traces dans la carotte 48. Les losanges représentent les données obtenues sur les échantillons lavés et les carrés celles obtenues sur les échantillons bruts, sans traitement au préalable. Les datations proviennent des corrélations stratigraphiques avec les sondages 86 et 15 (Fig. 3).

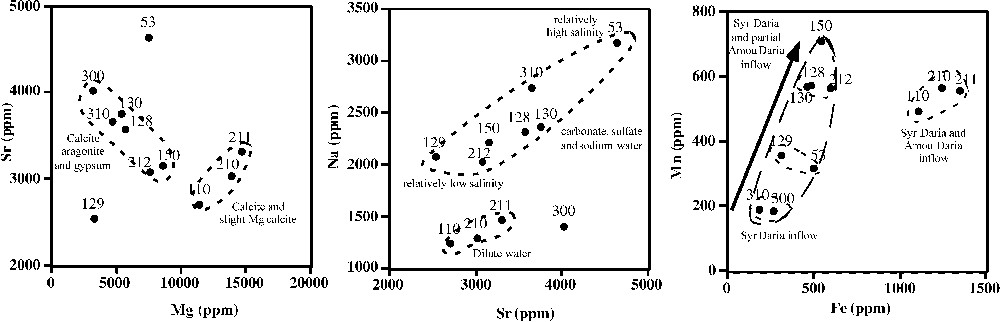

Correlations between Mg, Sr, Mn, Fe and Na from the carbonate phase of the bulk washed sediments in core 48 (Great Sea, Aral Sea).

Corrélations entre les teneurs en Mg, Sr, Mn Fe et Na de la fraction carbonatée de la carotte 48.

3 Conclusion

La régression actuelle observée n'est pas la première subie par la mer d'Aral. De nombreuses autres se sont succédées depuis l'Holocène. Tous les bas niveaux sont marqués par des dépôts carbonatés, les analyses géochimiques établissant le volume relatif de l'alimentation en eau par le Syr Daria et/ou l'Amu Daria. Durant les périodes où l'Amu Daria est détourné en totalité ou partiellement vers la mer Caspienne, les sédiments enregistrent des eaux du bassin riches en sulfates et pauvres en Fe et Mn. Au contraire, au cours des épisodes où une partie plus importante des eaux de ce fleuve peut se déverser dans la mer d'Aral, les dépôts sont plus riches en Fe, Mn et en calcite faiblement magnésienne.

1 Introduction

During the 1960s, since the expansion of intensive irrigation and the river water diversion for cotton cultures, the Aral Sea has been in the process of draining. The sea level has fallen by 25 m and the salinity has increased from 10 to 40 g l−1 in 40 years [22]. As the annual atmospheric precipitation is a minor component of the water balance of the sea (150 mm yr−1), the major flow of fresh water (90%) comes from the Amu and Syr Daria tributaries (Fig. 1) [8,10]. Several high and low levels of the Aral Sea have been induced by high and low fluvial inputs during the Holocene [1,3,4,6,14,16,25,28,33,34,38]. The high level leads to silty deposits and carbonates are observed during low levels. The main goal of this preliminary work is to discern more precisely the origin of the water inputs and the evolution of the hydric balance of the Aral Sea during low-level events using the mineralogy and the geochemistry signatures.

2 Geographical and geological setting

The Aral Sea (Central Asia, longitude 60°E and latitude 45°N) is located in the Turan plain, which is bordered to the southeast by the Tien Shan (7440 m) and the Pamir mountains (7495 m, Fig. 1). Its two main tributary systems are fed by ice melting and flow from these mountains: the Syr Daria across the Kyzyl Kum desert and the Amu Daria across the Kara Kum desert [8,12]. During the Pleistocene, based on geological, geomorphological and archaeological studies, the Syr Daria seemed to be the only constant tributary while the Amu Daria flowed into the Caspian Sea via the Uzboy Valley [4,6,15,16,19,23,25,38]. The Amu Daria has discharged into the Aral Sea only intermittently since 22 000 yr BP [2,15]. To the north, the Irgiz River flowed also in the Aral Sea, but today it is a dry delta. Compared to the main tributaries, this river seemed to have played a minor role in the control of the Aral Sea level during Holocene, but very few data are available [13].

Geomorphological data and the presence of Cardium edule, which penetrated in Aral during its connection with the Caspian Sea, indicate that Aral Sea was exoreic in the Lower Holocene. The progradation of the Amu Daria delta, due to orogenic activity and an increase in the sedimentary inputs, closed the connection with the Uzboy Valley before 7000 yr BP [27]. The natural evolution of the Aral Sea hydric balance has been also complicated by human activity mainly through conflicts and irrigation which began between 10 000–9000 yr BP in the southern part of the basin and around 3000 yr BP to the north [5,6,11,21].

3 Sampling and methodology

The studied core (No. 48, 4-m length) was drilled (piston tube cores) at a water depth of 25 m, in the central part of the Aral Sea (Fig. 2). The deposits mainly correspond to silt and carbonate alternations (3 m) which overlap 1.70-m-thick alluvial sands (Fig. 3). The study has been performed only on seven low-water-level deposits with which we have been provided by Russian colleagues. Sampling corresponds to a sand bed at the base of the core, to a gypsum-rich deposit at 310–300 cm and to five calcium carbonate sediments (from 215 to 210 cm, from 155 to 150 cm, 130 to 128 cm, 115 to 110 cm, and 55 to 51 cm). The chronology is established by lithological correlations with cores 15 and 86 (Figs. 2 and 3 [26,32,33]). Radiocarbon dates (14C) are provided from 13 levels (9 from core 86 and 4 from core 15 [9,24,25]) and from extrapolation between the dated levels.

The mineralogical composition is determined by optic microscope observations and the semi-quantitative estimation by X-ray diffraction.

For the carbonate geochemistry, high chloride and sulfate contents in the Aral Sea sediments can interfere with the analysis. They must be eliminated before carbonate leaching. Two mineralogical and geochemical analyses were therefore performed on the same crush sample. A first portion of the powder has no preliminary treatment and a second one is washed with hot distilled water (90 °C). The conductivity of the leached water and the mineralogical composition of the washed powder have established that, after this preliminary treatment, the major part of soluble chloride and gypsum is removed. All samples (unwashed and washed) have been leached in acetic acid (6%, 1 h) and analysed in HCl matrix solution by AAS on Hitachi Z.8100.

4 Results

4.1 Mineralogy

The carbonate minerals in sediments are low magnesian calcite, slightly magnesian calcite and aragonite that can all be associated with gypsum. The detritic phase contains quartz and clay minerals, mainly kaolinite and smectite (Table 1). Quartz is the major component of the alluvial sand (bottom of the core, Fig. 3) and of the base of the first low-water-level deposit (310 cm). Gypsum and low magnesian calcite have also been determined and are more abundant in the upper part of the level (305 and 300 cm). This mineralogical change reflects the beginning of the lake sedimentation. In the levels 212–210 cm and 150 cm, low gypsum content is observed and the detritic phase (quartz and clay minerals) is associated with slightly magnesian calcite. At the 129–128-cm depth, gypsum is again abundant, with low magnesian calcite, aragonite and detritic minerals. The upper part of the core (110 and 55–51 cm) is poor in gypsum and in detritic minerals, but rich in calcium carbonate.

4.2 Strontium, magnesium and sodium: mineralogical versus salinity control

The soluble acetic acid fraction from all samples ranges from 40 to 70% (Fig. 4). Data are very similar for unwashed and washed samples except for levels at 305 and 300 cm, which are rich in gypsum. For trace-element contents, data from duplicate washed samples and from samples without preliminary treatment are similar (Fig. 4), but not for sodium. Higher contents are observed in unwashed samples (probably remove from NaCl or other evaporitic minerals). The data set shows high values in strontium contents (up to 3000 ppm, Fig. 4). This can reflect the aragonitic composition of the sediments. Sr high incorporation coefficient is observed in aragonite (

The Mg contents are also relatively high, with large fluctuations from 3000 to 15 000 ppm (Fig. 4). As neither dolomite nor protodolomite has been determined by X-ray diffraction analysis, the higher magnesium contents can be linked with the occurrence of magnesian calcite (Table 1).

The SrMg correlation diagram shows two sample sets (Fig. 5). The first one (samples 310–300, 212, 150 and 130–128 cm) with a negative correlation

In the NaSr diagram (Fig. 5), the two same sample sets are observed and each shows a positive correlation. The first one, which is Na- and Sr-rich, defined by levels 212, 130–128, 150, 310 and 53 cm, is correlated with the Mg-poor sample group. The second is Na- and Sr-poor and corresponds to the Mg-rich set. It is defined by samples 110, 211–210, 305 and 300 cm. The comparison of the Na contents for both washed and unwashed samples (Fig. 4) shows that measured sodium in washed samples comes mainly from the carbonate minerals. Sodium is incorporated in the calcium carbonate lattice by calcium substitution [30,39,40]. So, the strontium and sodium content trends mainly reflect the salinity fluctuations. We can conclude that levels 212, 130–128, 150, 310 and 53 cm have recorded relatively more high water salinity.

4.3 Manganese and iron: control by the Aral Sea tributaries

In the MnFe diagram, the samples are also plotted in the two same sets (Fig. 5). In the first one (levels 310–300, 212, 150, 130–128, 53 cm), the Fe content is lower than 600 ppm and a MnFe positive correlation is observed. The second one (samples 211–210 and 110 cm) is Mn- and Fe-rich (respectively 500–600 ppm and 1110 to 1347 ppm).

Carbonate manganese and iron contents reflect the chemical weathering in the catchment basin and/or the redox condition change in the Aral Sea. It is well known that Mn and Fe dissolved contents are higher in reducing conditions, but in the studied part of the sea, no significant lithological redox fluctuation is observed. Sulphur is not present and sulphate interstitial water concentration is high only in the bottom of the core; low values are otherwise measured (from 0 to 3%) in the overlying sediments [17,32].

Related to the chemical weathering, carbonate Mn and Fe contents can therefore reflect different geochemical input with tributaries runoff. The water chemistry of the rivers is very distinct [7,20]. Compare to the one of the Amu Daria (AD), the chemical particulate and dissolved inputs from the Syr Daria (SD) water are enriched in sulphate (dissolved

5 Discussion

Sea level and water chemistry of the Aral Sea are mainly controlled by the partition between inputs from the Amu Daria and the Syr Daria, as atmospheric precipitation is very low. The increase in evaporation due to climate change is relatively negligible in the fluctuations of the sea level and of the salinity [2,36]. Since the beginning of the 1950s, there is no evident correlation between the Syr Daria discharge and the sea-level fluctuations, in contrast to Amu Daria [2,29]. Dynamic models on the recent period also show the influence of the climate change and natural (tectonic) or anthropic withdrawal on the water inflow to the Aral Sea [2,29].

The tectonic control is difficult to estimate. The Aral Sea–Sary Kamysch depression is bordered by up-thrown tectonic blocks to the west and is divided into several subsided fault blocks. Geomorphological study relating to the last 75 years estimates the epirogenic uplift about 0 to

Geological, geomorphological and archaeological studies have specified climate and anthropic influences on the water inflow changes of the tributaries. The present chemical and mineralogical data on low water level deposits lead to distinct more precisely the different water input from the tributaries.

(i) A major environmental change is recorded at the bottom of the core. The levels 310–300 cm (approximately 7500 yr BP) correspond to a transition between the azoic sand and the fossiliferous silts and carbonates. This event is correlated with a major regressive event known as ‘Old Aral’ [16,19]. The Aral Sea water salinity was high and was probably close to the present-day values (around 40‰ [22]). Our geochemical data lead us to conclude that the Syr Daria was the main tributary of the Aral Sea. Archaeological studies support this hypothesis.

(ii) Two other relatively high-salinity periods are observed. For the deposits at 130–128 cm, a part of the Amu Daria water input has been diverted for artificial intensive irrigation worked between 5000 and 4000 yr BP [11]. Around 970 yr BP (53 cm), natural sediment accumulation in the delta from 1600 to 450 yr BP and the devastation of the irrigation channels by Gengis Khan led to the total diversion of this river to the Sary Kamysh. The main source of water was the Syr Daria and it was the major regressive event in the Aral Sea's History [26]. Water was mainly carbonated, sulphated and rich in sodium. Precipitations in the studied part of the Sea corresponded to gypsum, aragonite and calcite with low Fe contents.

(iii) During the other low-water-level events, around 6200 yr BP (212–210 cm) and 3610 yr BP (110 cm), the water was less salty and sulphatic than during the previous studied periods. Water dilution of the Aral Sea was due to water influx from both Syr Daria and Amu Daria. Mineralogy of the deposits corresponded to calcite, Mg slight calcite and high Fe contents. The major source in iron was the Amu Daria.

The 150-cm level (around 5800 yr BP) is an intermediary state. It is contemporaneous with a climate change as determined by palynological studies in the Asiatic area marked by an increase in the atmospheric temperature and rainfall [6,18,28]. The contributions of both tributaries were important and led to a high water level in the Aral Sea.

It is well known that, during the Late Pleistocene and the Holocene, contrary to the Syr Daria, the course of the Amu Daria was more complicated near the Aral Sea, with secondary networks towards the Sary Kamysch via the Uzboy Valley. Climate controlled several reroutings and water losses of the Amu Daria. For example, during pluvial periods, the water level in the Amu Daria was high and the river flowed to the Aral Sea and to the Sary Kamysh [1,35]. But during warmer and much drier conditions, as around 3500 yr BP, the discharge to the Sary Kamysh decreased considerably and the water input from the Amu Daria in the Aral Sea was high [1,35].

6 Conclusion

The present regression of the Aral Sea was not the only one recorded in the sediments since the beginning of the Holocene. The low water level events are mainly defined by carbonate deposits in the central part of the Aral Sea and gypsum or mirabilite near the borders. From the sedimentological and geochemical data of the carbonate sediments, water-chemistry changes have been distinguished. Some low level periods are characterized by high salinity due to more sulphated and sodium-rich water. During others, waters are more diluted but present high Fe contents.

These alternations reflect changes in water inflow of the rivers (Syr Daria versus Amu Daria) during the Holocene. The Syr Daria was a relatively constant tributary of the Aral Sea whereas the Amu Daria was an intermittent one. Archaeological, sedimentological and geomorphological studies agree the geochemical data to confirm the Amu Daria withdrawal events around 7500, 4956 and 970 yr BP. Around 6200 and 3610 yr BP, the two tributaries flowed to the Aral Sea and the sea-level fall was less important.

Vous devez vous connecter pour continuer.

S'authentifier