1 Introduction: Lake evolution, climate change and ecological issues

Observation of the spatial and temporal variability of water resources is crucial for societal and scientific issues. The volume of water stored within lakes and reservoirs is a sensitive proxy for precipitation and may be used to study the combined impact of climate change and water-resource management. A lake system is a complex interaction between the atmosphere, and surface and underground water, responding to climatic conditions, but tempered overall by upstream water uses for agriculture, industry or human consumption. The overall water volume (a function of surface area and lake level) depends then on the balance between the water inputs and outputs. The inputs are the sum of direct atmospheric precipitation over the lake and surface runoff. Underground seepage can also provide inflow. Though this is usually a minor component of the water budget, it can be an important source of chemical transport [49]. Volume outputs are the sum of the direct evaporation from the lake's surface with river outflow and groundwater seepage. Some of these water balance components can be easily measured (river runoff, precipitation, lake level), while others can only be deduced from hydrological or climatic modelling (evaporation, underground water).

1.1 Water-balance components

Change in lake volume is a key parameter of the water budget (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

It requires level variation measurements (available from gauge instruments installed on the lake shoreline or derived from radar altimetry observations), and hypsometric curves or bathymetry maps to transform level into volume. One critical point is the precision of the bathymetry map. Small deviations can lead to large errors in the computation of volume variation [14,49].

The establishment of a hydrological water budget appears simple, but in practice is not so trivial. This needs accurate and continuous measurements, and a broad understanding of physical interactions between the lake and the atmosphere. Lake evaporation is generally an unknown but critical parameter and few methods of determination exist: the most accurate is the method of energy-budget, which requires knowledge of numerous physical parameters (water temperature, radiation, air temperature, saturated and air vapour pressure, wind, etc.). Other ‘empirical’ methods (more than 30 such methods exist in the literature) are more frequently used [24,49]. Groundwater flux between lake and subsurface is also difficult to measure, but can be acquired through the use of seepage minipiezometers [49] or modelling the groundwater flow system. Operation of minipiezometers does not permit continuous monitoring, while modelling requires many tests and complex geological investigations. As a consequence, groundwater fluxes are generally considered as negligible or defined as a constant value in the water budget equation.

Measurement of precipitation via rain gauge presents another large uncertainty. The problem is due to high variability in space and time and the paucity of gauge locations. The problem is generally amplified over lakes because of the inability to measure rain directly over its surface area, and precipitation on the shoreline and on the lake can differ markedly for large lakes. In some cases, lake evaporation can return to the lake as precipitation. Several of the large African lakes have greater direct lake precipitation (Victoria by 30%, Tanganyika by 20%) than over their catchments areas. Global precipitation databases (constructed by meteorological centres such as the ECMWF or the NCEP) do exist and are freely available on the Worldwide Web, though discrepancies with published climatologies are apparent. For example, comparison between NCEP and a climatology published by New et al. [36] for Lake Issykkul (Kirgizstan) and Lake Titicaca (Peru) reveals a factor-2 difference between the annual average precipitation. A large literature database exists for the Aral Sea, but differences of up to 100% exist between different sets of precipitation [14]. Satellite missions such as TRMM and the future GPM may offer precipitation datasets in the future.

Surface water flow, measured by runoff gauge instruments on many river systems is often not available for many rivers entering or leaving lakes. Maintaining such a device is expensive and many rivers in the world are not monitored or the data not released into the public domain. Braided streams are difficult to gauge, and uncertainties can be added to the hydrological water balance when gauges are installed too far upstream (in case of delta like in the Aral Sea [14] or when the gauges ceased to work operationally (Lake Chad [12]). Although no satellite-based instruments can monitor changes in storage volume, there exist now many imaging and altimetric instruments with capabilities to map a real extent and to monitor the variation in lake stage, respectively. This presents new opportunities to better determine the water mass balance, particularly for poorly gauged regions.

1.2 Behaviour of lakes under hydrological condition changes

The volume of stored water will vary with time according to changes in the hydrological budget. Under a constant climate scenario, the volume will tend towards an equilibrium level over a given time period, displaying a perfect balance between inflow and outflow [33]. If one of the components varies, for example, the lake level will change to compensate and reach a steady state. If a further change in water balance occurs before the lake has reached its equilibrium level, then the lake will find a new equilibrium state. Lakes and reservoirs will thus exhibit seasonal changes in surface area and level due to proportional changes in precipitation and evaporation. Mason et al. [33] stated that for the 200 largest lakes, one can use lake level and area variations to monitor climate variation via an ‘aridity index’, which ranges in value from 0, for very arid lakes, to 1, for lakes situated in humid zones. The authors' formalised sets of relations between the equilibrium return time and the lake geomorphology. Through these relations, the lake level records alone could then be used to compute the aridity index variation and therefore note the changing climatic conditions in the lake basin. Note though that there is scope for erroneous interpretation if human activities are the source of the original lake volume perturbation.

Nonetheless, the assessment of lake water balance could provide improved knowledge of regional and global climate change and a quantification of the human stress on water resources across all continents. The choice of the lake is an important factor. Hostetler [24] noted that deep and steep side lakes are good proxies for high-amplitude/low-frequency changes, while shallow water basins are better target for rapid low-amplitude changes. The latter are extremely sensitive for revealing decreased water input and rising evaporation.

Observation of many lakes in different climatic and regional zones can be utilised to discriminate between global and regional climate and anthropogenic phenomena occurring on different time and spatial scales. For example, some lakes located in the Andean Mountains are sensitive to ENSO sequences being more sensitive to precipitation variations in a humid region. Other lakes are more affected by global warming in the form of changing glacier feed. Examples include Lakes Argentino and Viedma, located at the border of Chile and Argentina [13,15,51].

The East African Rift region, covered by a dense network of natural lakes and some regulated reservoirs is also of interest. Here, lakes are not only influenced by global climatic conditions, but affect the regional climate themselves due to their size. Nicholson and Yin [37] have shown that precipitation over Lake Victoria is greater than over its catchment area by more than 30%. However, the main components of water balance (evaporation and precipitation) for the East African lakes are still very uncertain and assessment of water balance and connection to regional climate variability is an ongoing debate [6,37]. Based on seven years of satellite radar altimetry data from the TOPEX/Poseidon mission and the utilisation of precipitation data over East Africa and the Indian Ocean, Mercier et al. [34] showed evidences of hydrometeorological linkages between the Indian Ocean sea-surface temperature (SST) and precipitation effects over the East African continent, and the changes in lake levels. New satellite radar altimetry missions (Jason, GFO, and Envisat) have recently increased the number of lakes observable over East Africa and climate studies continue.

Arpe et al. [5] showed a strong linkage on a decadal time scale between the level variation of the Caspian Sea and the El Niño southern oscillation (ENSO). Because the Volga river discharge (VRD) and the sea evaporation both dictate the evolution of the Caspian Sea level, the authors showed that the equatorial Pacific SST variability could be used to simulate the VRD and via validation exercises showed good correlation with the observed discharge. Other decadal climate fluctuations such as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) and the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) can also significantly change the water circulation in the atmosphere, and so affect lake level changes across large regions. The NAO could prominently influence climate variability over a continental scale affecting the freshwater ecosystems of Europe, Central Asia and the US.

General circulation models (GCM) that have been developed to assess the effect of the so-called ‘greenhouse effect’ have shown that one of the consequences of global warming would be significant changes in precipitation and surface temperature [16,50]. This will have an impact on regional hydrology and ultimately affect lake and reservoir level. For example, the present-day decrease in the Arctic Lake total surface has been highlighted from a set of satellite images over more than 10 000 lakes in Siberia [47]. For some other locations (e.g., the North American Great Lakes), global warming could be accompanied by a drop in lake level or increasing level depending on which GCM is used to determine the effect of global warming [32]. Seasonal variation of the Great Lakes are also affected by global warming, as precipitation and runoff increases in autumn and winter, inducing higher extreme lake level [4]. Apart from the ecological consequences, problems associated with economic expenditure will also arise. Increasing temperatures in mountainous regions will accelerate the thaw of snow and glaciers, affecting both lake level and salinity, while in coastal regions variations in riverine outflow could affect heat exchange impacting thermal stratification and mixing dynamics [38,39]. The effects of climate change are still uncertain however, but the sustainable preservation of lakes worldwide depends on the extensive understanding of the processes that govern their potential evolution and the monitoring of these bodies via remote sensing.

The construction of reservoirs over the last 50 years and the potential effects on sea level rise have been discussed by Shiklomanov et al. [44] and Gornitz [20]. On a global scale, it could be assumed that reservoirs act as simple retainers of water and thus do not contribute to a general increase in elevation. While Shiklomanov et al. [44] estimated that since 1950 reservoir storage has contributed to a sea-level decrease of around 0.3 mm yr−1, Gornitz [20] quoted a water loss of 0.56–0.81 mm yr−1 and stressed that seepage loss, evaporation and sedimentation process are still unknown and associated errors can be high. However, the example of the Aral Sea (see next sections), which dramatically shrank after 1960 due to the building of irrigation channels and reservoirs across its drainage basin, reveals a potential negative effect on global sea-level rise.

1.3 Present-day lake-level monitoring

The systematic, global monitoring of these water bodies is becoming a fundamental objective of the international community (as faced by United Nations' organisations, numerous governments, and other public or private institutions), but the decline in ground-based gauge information has dramatically increased during the last decade [2,3,48]. In many regions, the expense of data collection is restricted due to economic reasons, or the collected data is restricted, being considered as sensitive national information. The physical removal of gauges from many lake domains is a common situation in many parts of the world. Nevertheless observation of the status of lakes and reservoirs and calculation of their water balance can be improved with the help of satellite measurements such as precipitation from the TRMM mission, and inundated surface extent or lake area from missions such as AVHRR, Landsat, and MODIS. While scientists are looking to the GRACE mission to enable estimates of the vertically integrated water mass change over large rivers basins, researchers continue to explore satellite radar altimetry data as a contributor of surface height variability. The techniques are now so well validated that lake and reservoir altimetric measurements can be found via several web sites:

Because water storage variability is mainly driven by a combination of meteorological input (precipitation, evaporation) and human water use, there is the need though to have both in-situ local and global datasets coupled with remote sensing measurements. Radar altimetry has been the dominant technique for lake-level contributions so far although lidar (laser altimetry) also shows promise [10,22,23]. A number of authors have explored the radar application over inland waters, more generally [7,35] or to more specific lake basin case studies [1,8,10,11,14,34]. These studies show that radar altimetry is an effective and powerful technique with many potential applications: assessment of hydrological water balance [11,14], prediction of lake-level variation [12], studies of anthropogenic impact on lake's water storage [1], correlation of interannual fluctuation of lake level on a regional scale with ocean–atmosphere interaction [34].

Here, we will summarise the principle of the altimetry technique and illustrate its potential by reviewing several test case studies on a diverse selection of water bodies.

2 Altimetry: principles and error budget

A full discussion of the derivation of altimetric heights and their associated errors can be found elsewhere [7]. A summary is provided here.

The altimeter transmits a short microwave pulse in the nadir direction, and the resulting echo reflected by the surface is examined in the time domain. The time for the pulse to be reflected back to the altimeter corresponds to the distance (or ‘range’) between satellite and earth surface [19]. The altimetric height H of a non-ocean surface is determined by the difference between the satellite orbit (Alt) and the altimeter range measurement, with a final correction for earth tide effects.

With knowledge of the satellite orbit, the difference between the corrected range and the orbit, reveals the height of the surface above a given reference datum (the reference ellipsoid). Due to the inhomogeneous mass distribution within the Earth, the altimetry measurements can be further corrected for the height of the geoid above the ellipsoid of reference [19]. For continental water bodies, a low-resolution terrestrial geoid like EGM96 can be utilised [31], the data being first averaged across the lake over a given period to remove all periodical and random fluctuations and so reveal a more precise Mean Lake Surface (MLS). However, for small lakes, this computation introduces additional errors due to lack of averaging data to average properly for the geoid slope along and cross track.

The derivation of time series of surface-height variations involves the use of repeat track methods. This methodology employs the use of a mean (reference) lake height profile. This is derived from averaging all height profiles across the lake expanse within a given time interval, effectively smoothing out the varying effects of tide and wind set-up. The height difference between the reference pass and each repeat pass enables the time series of lake-height variation to be created.

To date, a number of satellite radar altimeter missions have been launched. Table 1 lists their temporal coverage, repeat periods, spatial coverage with respect to large lakes and reservoirs. Overall, stage accuracies range from a few to tens of centimetres. Minimum target sizes are dependent on a number of factors, including footprint size, topography complexity and instrument tracking logic. Table 1 gives approximations for each altimetric mission, but note that ongoing altimetric range and radar echo interpretation studies are aiming to improve expected elevation accuracy and minimum target size. Table 2 summarises the estimated rms error budget on a single 10-Hz TOPEX/Poseidon (or T/P) height measurement (taken from [7]). Summing the squares of the individual rms values derives the total height error. The range precision will be improved, as a mean lake height (across the profile) is determined, effectively averaging all valid height measurements (N) from coastline to coastline.

Summary of satellite altimetry general characteristics

Résumé des caractéristiques générales de l'altimétrie satellitaire

| Satellites | Operation period | Orbital cycle | Accuracy | Minimum target area and width |

| ERS2 | 1995–2002 | 35 days | >9 cm rms | |

| ENVISAT | >2002 | 35 days | >9 cm rms | |

| T/P | 1992–2005 | 10 days | >3 cm rms | |

| Jason-1 | >2002 | 10 days | >3 cm rms |

Total error budget for lake height

Erreur totale budgétée pour la hauteur du lac

| Contribution | Root-mean-square (cm) |

| NASA orbit | 3.5⁎ |

| Range precision | (variable) |

| Embias plus skewness | 2+1.2 |

| Earth tide | 1 |

| Dry troposphere | 0.7 |

| Wet troposphere, ECMWF/TMR | 3/1.2 |

| Ionosphere, DORIS | 1.7 |

| Minimum total (TMR/ECMWF) | 4.85/5.57 |

⁎ The removal of geographically correlated orbit error components via the use of repeat track techniques may reduce this value.

The accuracy of a single lake's height measurement then will vary depending on the knowledge of the range, the orbit and the various corrections. Range precision will vary according to the surface roughness and the selected satellite mission, as more complex tracking logic and algorithms try to maximize the quantity of data collected over continental surfaces. In practice then, it is important to note that altimetric height measurements are an average (across the effective footprint and across the lake profile) and in this way differ from a single-spot height at a given location provided by a traditional gauge. Validation exercises with ground-based gauge data give some measure of the expected accuracy for a similar target type and size. Comparison of T/P and Jason results with gauge data for the Great Lakes, for example, shows an accuracy ∼3–5 cm rms [45]. Although this accuracy will reduce for smaller lakes, the derived level variations are generally an order of magnitude higher than the total error budget. Ongoing research is examining the trade-off between minimum target size observable and acceptable height accuracy for the various hydrological applications.

3 Case studies

3.1 The lakes of Central Asia

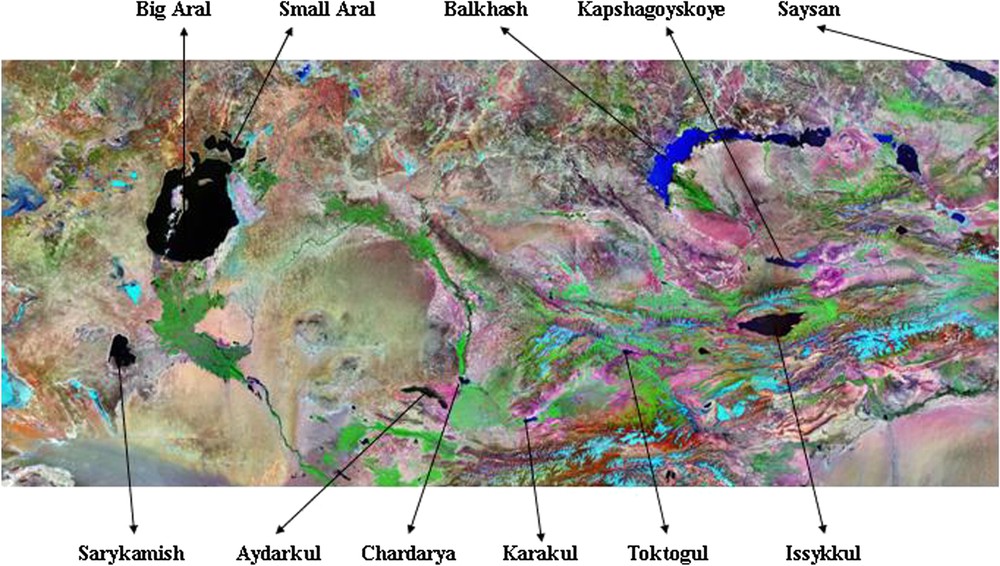

Fig. 1 depicts the lakes and reservoirs of Central Asia that are overpassed by satellite altimetry. Both the larger (Small and Big Aral, Issykkul, Balkhash) and smaller lakes and reservoirs (Sarykamish, Kapshagoyskoye, Toktogul, Chardarya, Aydarkul, Karakul) can be observed with the altimeter.

Central Asian lakes and reservoirs monitored by satellite altimetry (http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/; the image is constituted from a mosaic of Landsat images taken in 1990).

Lacs et réservoirs d'Asie centrale observés par altimétrie satellitaire (http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/ ; l'image est constituée à partir d'une mosaïque d'images Landsat collectées dans les années 1990).

This figure illustrates the potential of altimetry in large basins water monitoring, in particular in regions where in-situ data are lacking, or not available. We are going to show how altimetry can be used to explore various water-resource situations in this Central Asian region.

3.1.1 Aral Sea

The Aral Sea is located in an arid zone, characterised by marked differences between summer and winter temperatures and has low precipitation all year round. Evaporation is approximately ten times greater than precipitation, the sea being maintained at equilibrium by the inflowing waters of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya. These two rivers originally provided around 60 km3 yr−1 of fresh water, roughly half of their total capacity. Around 1960, a decision was made to develop an intensive cotton and rice economy. In such an arid zone, irrigation provided the means to reach the planned agricultural objectives of the Soviet Union government. Large-scale development of ground infrastructure (irrigation channels, reservoirs) began and the extent of the irrigated area increased from 4 billion to 8 billion hectares. The volume of water utilised for irrigation increased up to about 100 km3 yr−1. The effect on the level of the Aral Sea was drastic, dropping from +53 m (above the 0 Baltic sea level) in 1960 to +40 m in 1989. This decrease led to the separation of the sea into two lakes, the ‘Small Aral’ to the north and the ‘Big Aral’ to the south. From 1989 to 2005, Small and Big Aral were separated and evolved in different ways. With the T/P altimeter, which overpasses both new distinct lakes, it was possible to measure precisely the level variations from 1992 until now. The elevation of the Big Aral reached a low of +30 m in 2004 [14]. The corresponding decrease in surface extent and volume was 67 000 km2 and 1083 km3 in 1960 [9] to 16 000 km2 and 100 km3 in 2004 [14]. The difference between evaporation and precipitation for the Big Aral represents an average loss of 25–30 km3 yr−1 over the last decade, while river discharge from Amu Darya have varied from 0 to 15 km3 yr−1 in the 1990s. Overall, the Big Aral shrank during this period at a rate of 60 to 80 cm yr−1.

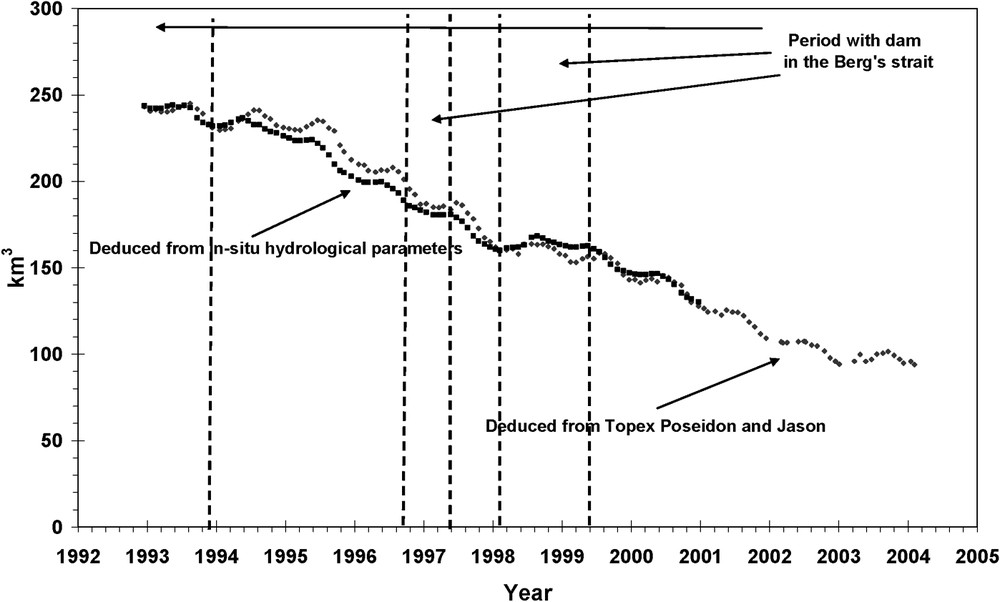

Satellite remote sensing also allowed a method of exploring the complex new hydrology. Using a combination of precise digital bathymetry map (DBM) of the basin with level variation deduced from altimetry, Crétaux et al. [14] computed the resulting volume variation of the Big Aral Sea for the period 1993–2004. They showed that the reduction of the lake volume as measured by T/P, GFO and Jason is smaller than that deduced from examination of the hydrological budget (Fig. 2). There are errors within both methods, but the possibility of an additional positive water inflow to Big Aral (5 km3 yr−1 [14]) via significant underground water inflow cannot be ignored. This conjecture needs to be further assessed by hydrogeological modelling and more accurate data on the evaporation and precipitation rates.

Big Aral Sea volume variations, deduced from in-situ measurements and from altimetry data [14].

Variations de volume de la grande mer d'Aral déduite de mesures in situ et de l'altimétrie [14].

Even if this can be accurately established, the groundwater flow will likely only slow the desiccation of the Big Aral. To reverse the process or even to stabilise the sea level to the level of the mid 1990s would require more underground flow than it could be even supplied in the most optimistic scenarios [14].

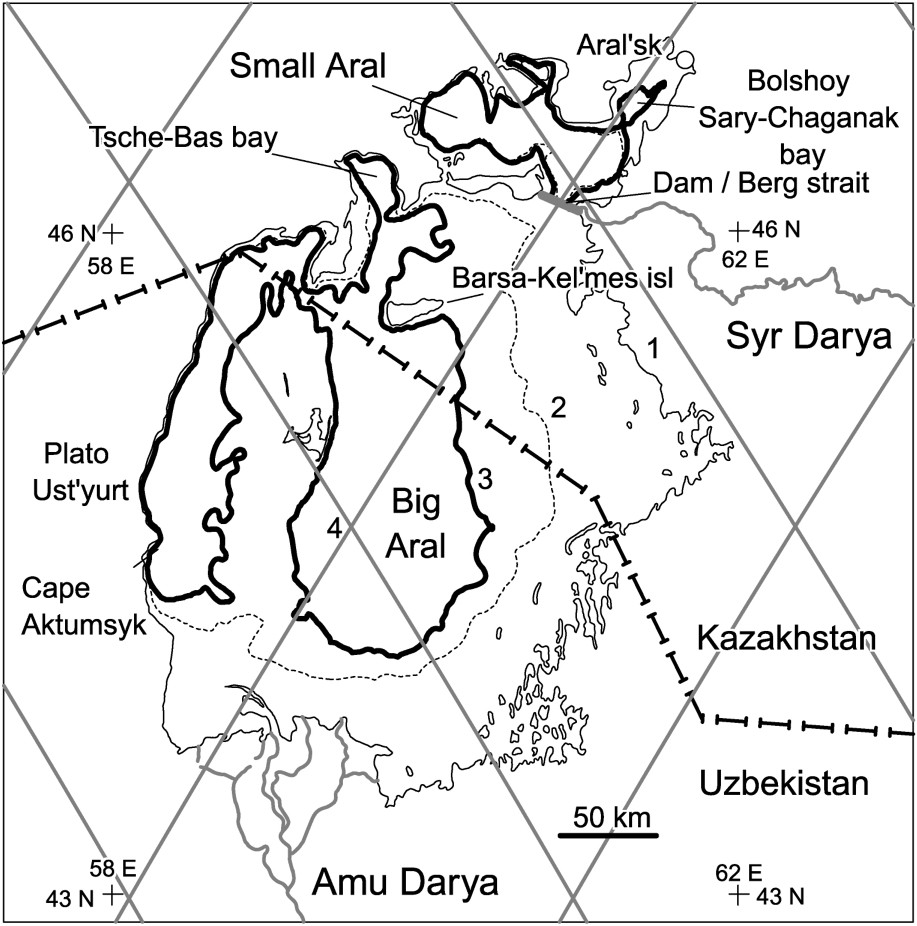

For Small Aral, the situation since 1989 is radically different. It has continued to be fed by the Syr Darya River, and has dried up at a lower rate than its counterpart. There are two main explanations: first the area of the basin is much smaller, which diminishes the effect of evaporation, and secondly, during the years 1992 to 1999 a dam was built in the Berg's strait (see Fig. 3), which stopped the loss of water from the Syr Darya into the desert. This dam was destroyed (and rebuilt) three times during this period.

The Aral Sea. Location of the Aral Sea coastline in 1966 (1), 1992 (2), 2002 (3), and TOPEX/Poseidon ground tracks (4) (from [14]).

Localisation des cotes de la mer d'Aral en 1966 (1), 1992 (2), 2002 (3). Traces TOPEX/Poseidon (4) (d'après [14]).

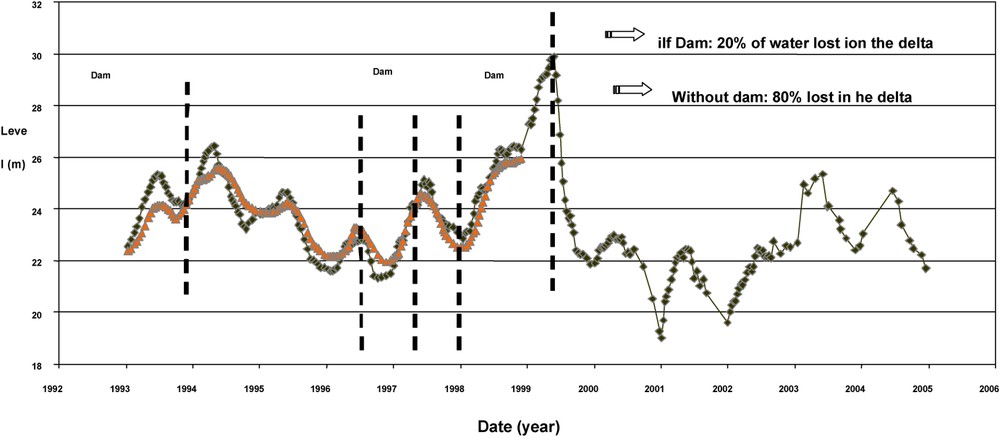

Aladin et al. [1] demonstrated that during the period (1993–1999), the existence of the dam allowed some restoration of the Small Aral. They computed that during periods of dam absence, only 20% of the river runoff as measured at Kazalinsk (Fig. 3) reached the sea. The rest was lost by evaporation in the delta and in the desert, as well as by underground infiltration and probably by some inflow to the Big Aral through the Berg's strait. This computation (with uncertainties ∼20 to 25%) was fully based on comparison of volume variations deduced from a combination of altimetry and bathymetry data with volume variations deduced from the hydrological budget. The same calculation, when the dam was in place, showed that the dam allows water retention of 80% of the river runoff that enters via the Syr Darya delta (Fig. 4). This computation determined the correlation between the amount of water entering into the Syr Darya delta and the level of Small Aral [1].

Volume variations of the Small Aral Sea deduced from satellite altimetry (black stars) and from hydrological in-situ measurements (triangles). Amount of runoff data from the Syr Darya River to the Small Aral Sea have been adjusted considering initial values measured in Kazalinsk (from [1]).

Variations de volume de la Petite Aral déduites de l'altimétrie (étoiles noires) et de mesures in situ (triangles). Les débits totaux du Syr Darya dans la Petite Aral ont été ajustés en considérant les valeurs initiales mesurées à Kazalinsk (d'après [1]).

3.1.2 Other Central Asian lakes

Water resources monitoring and management in Central Asia have to take into consideration aspects of sustainable development, ecological impact of water uses and climate changes, and transboundary water policies. Water management is indeed becoming a political and societal issue that concerns different countries as the drainage basins of the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya, are shared by five different countries: Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kirgizstan and Turkmenistan. A political agreement was signed in the mid-1990s for a rational use of the water resources. Via the use of large reservoirs, both Kirgizstan and Tajikistan agreed to retain upstream water over the winter period for ultimate use by Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, who require a large amount of water downstream for irrigation in the dry season. As compensation, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan agreed to provide gas and electricity to Kirgizstan and Tajikistan. The agreement is a source of contention and is still being contested. This transboundary water management issue is needed to reinforce the collaboration between the water management agencies, and to highlight the maintenance of the water resources monitoring and the sharing of the river runoff, reservoir storage, and hydroclimatologic data. In fact, UNESCO, NATO and other international organisations aimed to strengthen this agreement by providing the framework to enhance the collaboration between political managers, hydrologists, and scientists in general. Both financial and technical tools have been developed to assess water storage evolution in the whole Central Asia, and space technologies have been widely utilised. Optical and radar remote sensing have been used for analysing soils and vegetation cover evolution, while radar altimetry could open up a new mode of lake and reservoir monitoring.

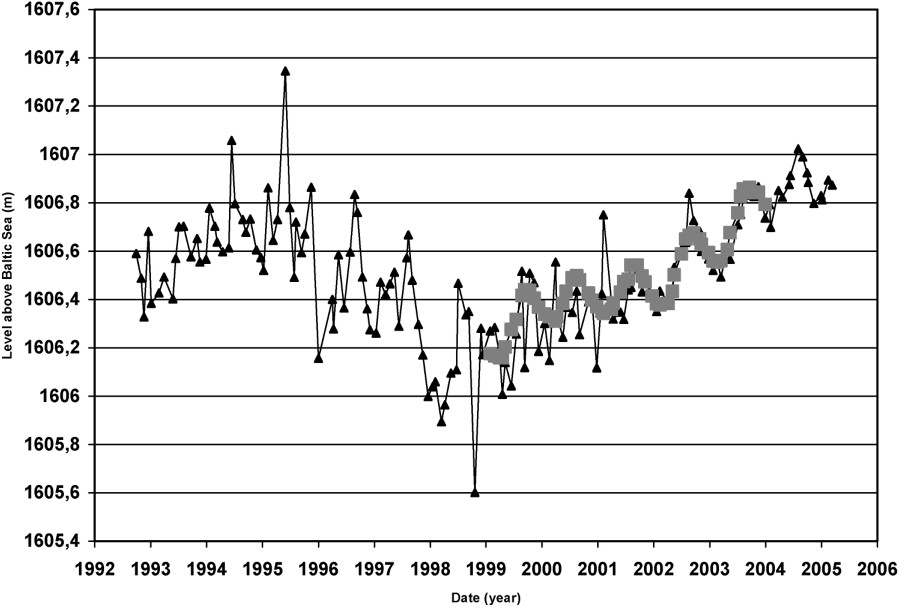

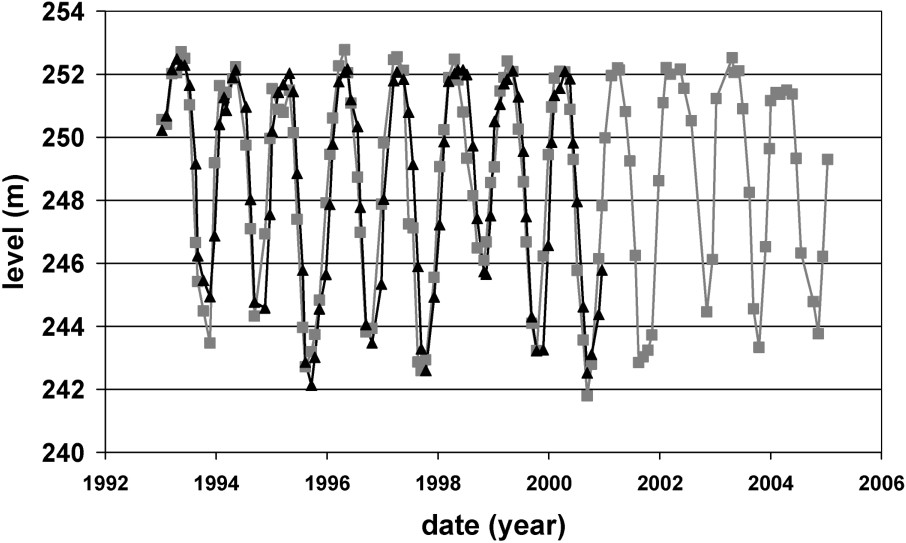

Several of these lakes are monitored by ground-based gauges, though access to current information (post-2001) is still restricted. Where there are overlap periods between gauge and altimeter observation, validation exercises reveal the typical accuracy of the satellite measurements. For example, accuracies of 5 cm rms (Fig. 5, Lake Issykkul), 10 cm rms (Fig. 6, Lake Chardarya, one of the storage reservoirs along the Syr Darya, and used to release water into Kazakhstan for irrigation purposes). In most cases, the radar altimeters continue to provide monthly stage data.

Lake level variations from altimetry on multi-satellite mode (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat & Jason) from http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/, versus in situ gauges provided by the IWP (Institute of Water Problem) of Bishkek for the Issykkul Lake (Kirgizstan).

Variations de niveau du lac Issykkul (Kirgyzstan) par altimétrie satellitaire, calculées en mode multi-satellite (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat et Jason) visibles sur le site http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/, comparées aux mesures in situ fournies par l'IWP (Institute of Water Problem) de Bishkek.

Chardarya reservoirs level variations deduced from in-situ measurements (black triangles: http://water.freenet.uz/) and from altimetry (grey square: http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/).

Variations du niveau du réservoir Chardarya déduits de mesures in situ (triangles noirs : http://water.freenet.uz/) et de l'altimétrie (carrés gris : http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/).

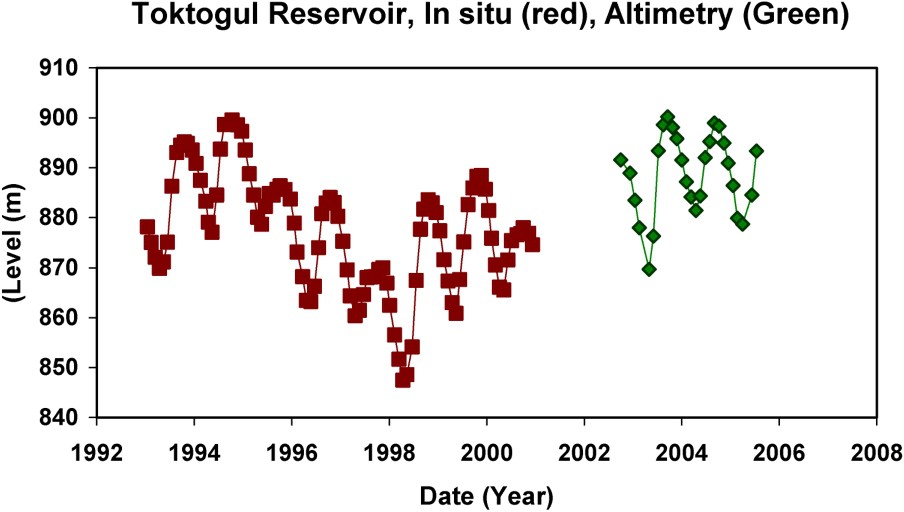

Fig. 7 shows the case of the Toktogul reservoirs, downstream from Lake Issykkul and located in Kirgizstan. In situ data are only available up to 2001, while satellite radar altimetry can only provide measurements from 2002.

Reservoir level variations from Altimetry on multi-satellite mode (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat & Jason) versus in situ gauges for Toktogul (Kirgizstan) (from http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/ and http://water.freenet.uz). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure text, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Variations du niveau du réservoir Toktogul (Kirgyzstan) par altimétrie en mode multi-satellite (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat et Jason), comparées aux mesures in situ (issues des sites http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/ et http://water.freenet.uz).

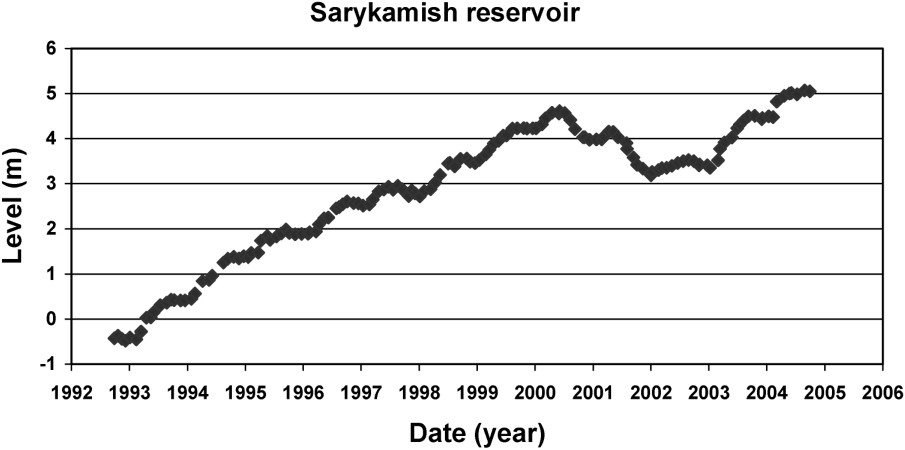

No gauge data is available for the Sarykamish reservoir, but altimetric measurements (Fig. 8) show the consequences of diverting the flow of the Amu Darya River. This political decision, made by the Republic of Turkmenistan in the early 1990s has speeded up the shrinking of Big Aral as the water intake from Amu Darya to fill in the Sarykamish Lake was initially feeding the Big Aral.

Reservoir level variations from altimetry on multi-satellite mode (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat & Jason) for Sarykamish (Turkmenistan) from http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/.

Variations de niveaux du réservoir Sarykamish (Turkménistan) par altimétrie en mode multi-satellite (TOPEX/Poseidon, GFO, Envisat et Jason), issues du site http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/.

3.1.3 Discussion

The results shown here (taken from http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/ for altimetry and http://water.freenet.uz/ for in-situ data of Central Asian reservoirs) highlight the fact that the altimetric accuracy is not homogeneous, but depends on the quantity and quality of the satellite data available on each lake or reservoir. One can see that altimetry is a good complementary source of information to the ground-based networks and can provide new information where gauges are lacking. In this respect, it provides an additional tool for decision-makers in the field of water management. We have seen that the impact of water uses the amount of released water from the big reservoirs, and diverting of the inflowing river has impacts on terminal lakes like the Aral Sea, and one can ignore neither the correlations between stage variations in the Aral Sea or those in its upstream reservoirs (Chardarya, Toktogul, Karakul...).

Monitoring the lake and reservoirs level in these regions also helps to study the impact of climate change on the lakes and reservoirs, though interpretation is complex. Lake levels may drop due to potential increases in evaporation, but levels may increase due to the increase in thaw rates of the surrounding glacier and mountain snow.

The recent increase of the Lake Issykkul level (Fig. 5) with a rate of around 10 cm yr−1 has been confirmed by both in-situ and altimetry data. This abrupt change of level variation could be the consequence of recent higher glacier melting [41].

Studies made by Small et al. [46] showed that global warming has also accelerated the shrinking of the Aral Sea by around 100 mm yr−1 from 1960 to 1990. With altimetry monitoring, it would be possible to quantify the impact of global warming on the Aral Sea during the last 15 years.

3.2 Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the largest inland water body of the world. With a mean salinity of ∼13 g l−1, it is located in a depression bordered by the Caucasian Mountains to the west, the Central Asian plateau and desert to the east, the Russian and Kazak plains in the north, and by the Elbruz Mountains to the south. The total basin catchments cover more than 3 billion square kilometres, and the sea is fed by numerous rivers including the Volga, Ural, Terek, and Kura rivers. The sea can be considered as being comprised of three parts, the northern Caspian, which is a shallow area with a mean depth of 5 m, the central Caspian, with a mean depth of 190 m, and the southern Caspian, with a mean depth of 350 m. The South Caspian is deepest at 1025 m [44].

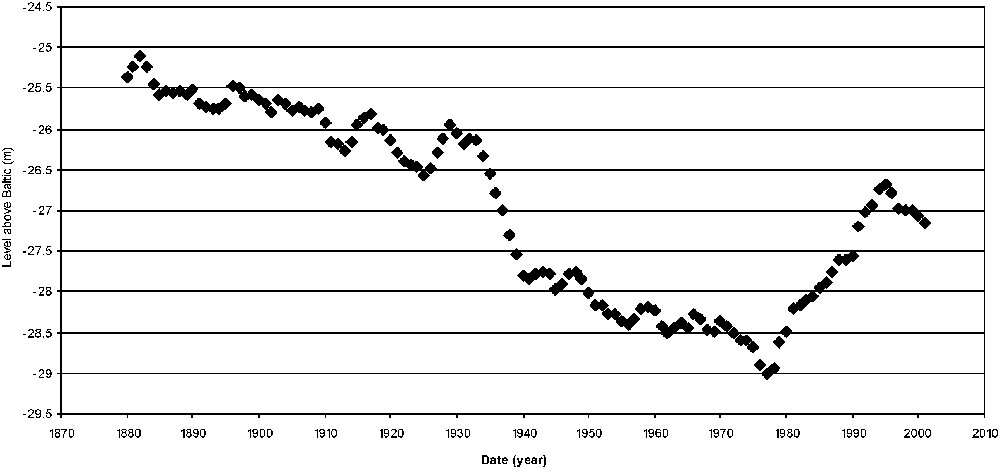

The Caspian Sea has been characterised by cyclic and high-amplitude water-level variations over historical time scales. For the last 2000 years, the sea level fluctuated around 15 m, but it has declined until ∼7 m over the last five centuries. Fig. 8 shows more recent level variations; note the minimum in 1979 and the subsequent rise, with corresponding surface area variations between 360 000 to 400 000 km2 [44]. They have been correlated with height oscillations between −26 and −29 m (with respect to the zero ocean level) during the last hundred years.

Coastal and delta areas are strongly affected by these considerable sea-level changes with subsequent damage on infrastructure and recurrent ecological disasters. The events have led to many investigations of the links between level variability and potential impacts [30]. The Caspian Sea has also provided a unique example to test global sea-level rise models and the possible impacts on coastal zones over a very short time of few dozen of years [30].

Adaptation of human activities, efficient use of water resources, sustainable development and ecosystem protection fundamentally depend on the variations of the Caspian Sea's water level. Water balance investigations can utilise more than a hundred years of ground-based data based on the network of hydrometeorological stations homogeneously scattered along the coast and Islands of the Caspian Sea. Averaged data from four stations (Baku, Makhashkala, port Shevchenko, and Krasnovodsk) provide an ‘official’ Caspian Sea Level (CSL) (Fig. 9), from which uncertainty in the water balance (mainly the evaporation rate) can be explored with a view to predicting the future evolution of the CSL [29,44].

Caspian Sea Level from in-situ data.

Niveau de la mer Caspienne à partir de données in situ.

A detailed description of the water balance components can be found in Shiklomanov et al. [44]. The Volga River provides more than 80% of the total inflow (400 km3 yr−1), and dictates the interannual variability of the Caspian Sea. Underground water inflow is about 3–5 km3 yr−1 and the precipitation rate is ∼250 mm yr−1, with high temporal variability. Evaporation represents the main outflow component (∼730 mm yr−1), without high temporal variability.

Discharge to the Kara Bogaz bay in the east has varied between 0 to 30 km3 yr−1 and depends on the level difference between the Caspian Sea and the bay.

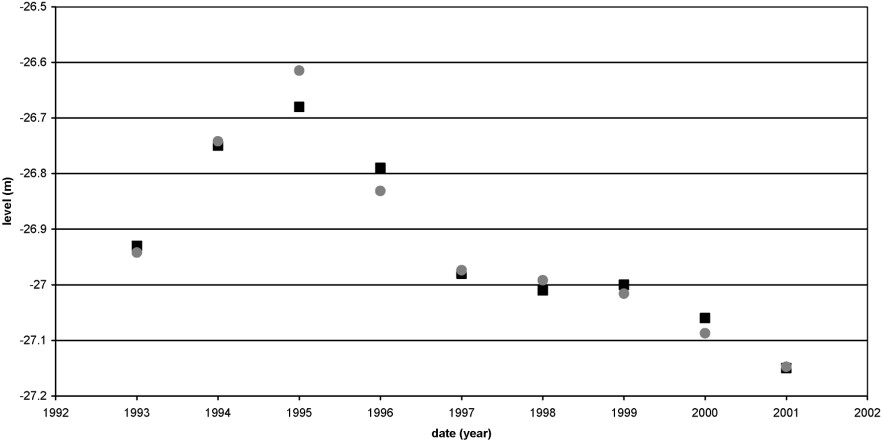

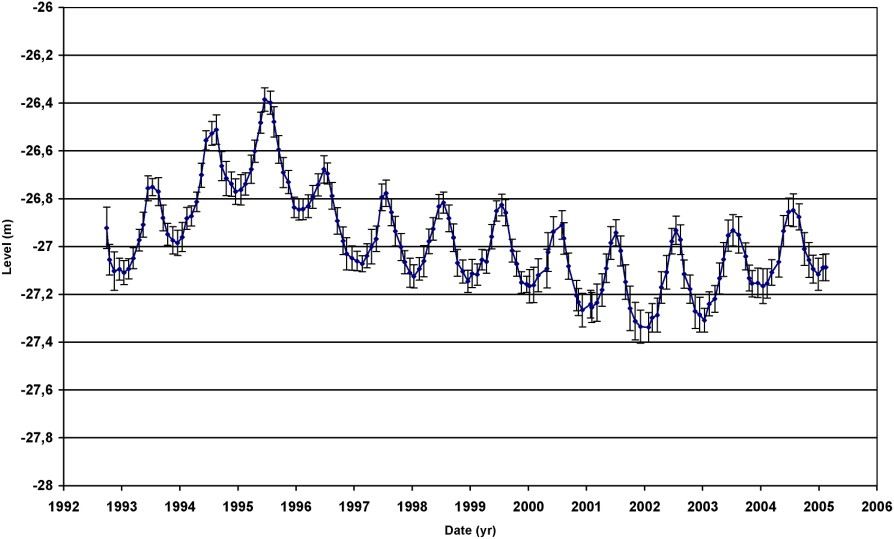

Recent radar altimetry measurements have helped to explore the water balance of the Caspian providing level variations at a time when gauge data is sparse. Comparisons of recent altimetry measurement and in situ gauges measurements are shown in Fig. 10 for the period 1993 to 2001. This figure demonstrates that the general trend of both time series are correlated but some discrepancies, in particular the ∼7-cm level in 1995, can lead to a ∼30-km3 difference in water volume. Fig. 11 shows the Caspian Sea level from radar altimetry up to 2005: http://www.legos.obs-mip.fr/soa/hydrologie/hydroweb/. Note the 60-cm decrease observed during the seven years following the peak in 1995, and ongoing rise after 2002. Seasonal variations of the sea level (∼20 cm) are mainly driven by changes in river runoff, evaporation, and precipitation.

Caspian Sea level variation from altimetry (grey circles) and from in-situ measurements (black square).

Variations de niveaux de la mer Caspienne à partir de l'altimétrie (cercles gris) et à partir de mesures in situ (carrés noirs).

Caspian Sea level variations deduced from altimetry measurements.

Variations de niveau de la mer Caspienne, déduites des mesures altimétriques.

3.3 Lake Chad, Africa – Seasonal prediction and regional vulnerability

Lake Chad lies at an altitude of ∼282 m above sea level in the Sahel region of Central Africa. The catchment area is immense, covering an area of . The climate in the vicinity of the lake is semi-arid in the south and arid in the north, with a dry season occurring between October and April. A short wet season (typically 550 mm yr−1 in the south and 250 mm yr−1 in the north) occurs between May and August. Approximately 90% of the lake's water stems from the Chari/Logone river systems. These rivers have their origins in Cameroon and the Central African Republic, where there are more humid zones with rainfall from May to September. The remaining 10% stems from local precipitation, and from the El Beid and Komadougou Yobé Rivers [17,18,28]. The lake is classed as ‘closed’, referring to zero water outflow, although [28] reports losses as high as 21% via ground water seepage, which occurs in the Southwest of the lake basin. With low humidity, high temperatures, and shallow lake depths (mean ∼5 m), ∼80% of the lake's water is lost through evaporation [40], with associated annual water-level variations of ∼1–3 m and large fluctuations of the surface area [25,26].

During the last 40 years, regional precipitation in the region has been reportedly low and there have been notable droughts between 1968 to 1974 and 1983 to 1985. This led to the drilling of many uncapped boreholes and a large-scale irrigation system was constructed in the south. Both schemes led to high evaporation losses and the irrigation system further failed due to the non-implementation of contingency plans during the drought periods [27]. The reduction in lake surface area, from ∼25 000 km2 in 1960 to ∼2500 km2 in the mid-1980s [21] clearly demonstrates the magnitude of the combined effects. There has thus been a slow desiccation of the lake from the north to the south, and exposed ancient dunes now dominate the northern and eastern boundaries of the original coastline. The only remaining area of permanent open water exists in the southern region of the lake basin, where it is surrounded by densely vegetated swamps and smaller pools. Each year, the Chari/Logone waters flow into the lake basin from the south and gradually move northwards, supplying the permanent open water and seasonally inundating the marsh regions.

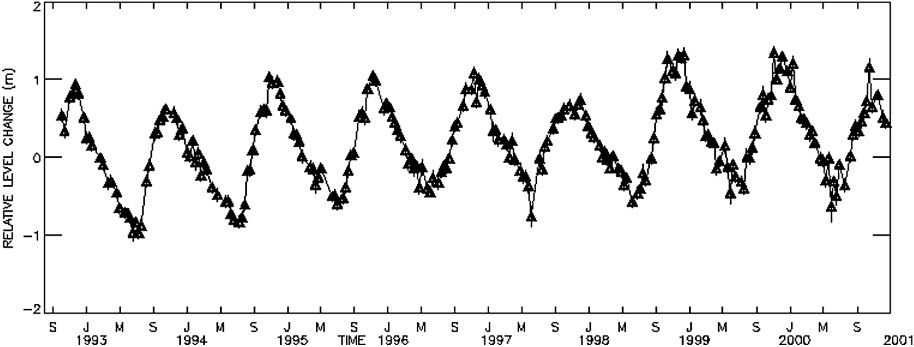

The diminishment of Lake Chad has had adverse effects on both food and water resources. The local population has learned to adapt to the reduced seasonal inundation of the lake basin, but is vulnerable to both droughts and excessive inflows. The lake however remains an important source of water and protein (fish) for both the sedentary and nomadic local people. With a current coastal population of ∼0.75 million, the introduction of flood retreat farming has been employed as one means of coping with the current situation. This practice utilises the moist soil bed revealed by the retreating floodwater to harvest a number of differing crops. As the waters rise, fishing replaces farming until the waters once again decline, and the harvesting cycle commences [42]. Recent studies [8,43] have discussed the plight of Lake Chad and have shown how remote sensing technology can monitor the ever-changing inundation conditions. The areal extent and duration of the floodwaters were observed via image analysis using the NOAA/AVHRR LAC dataset. The variation of the water level, within the permanent lake waters, the inflowing rivers, and the surrounding marsh lands were observed over a 10-year period using data from the TOPEX/Poseidon mission (1992–2002). With an accuracy ⩾10 cm rms, the altimetry revealed seasonal water-level variations of the order of 0.5–6 m and there was a notable rise in minimum levels, 15–35 cm yr−1 within the lake basin (Fig. 13). Peak-level phase lags of 4–5 months were also observed between the headwaters of the Chari/Logone Rivers and the western lake marshes. Image results reveal that the permanent lake area is ∼1385 km2, and that with an accuracy of ∼5% the surrounding regions have been additionally flooding by up to ∼3600 km2 yr−1 (Fig. 12). Despite current basin complexities, the synergistic area/level measurements corroborate the known hydraulic relationship at low water levels. Both measurement sets reflect the poor inundation years of 1993–1994 and 1997–1998 despite the indication of a general recovery in regional precipitation to the Southeast of the lake.

Time series of altimetric lake level variations for the permanent waters of Lake Chad. Data is taken from the TOPEX/Poseidon mission. Time axis is 4-month intervals.

Séries temporelles des variations de niveau pour la partie permanente du lac Tchad. Les données sont issues de la mission TOPEX/Poseidon. L'axe des abscisses représente le temps avec une période de 4 mois.

AVHRR LAC channel-2 noontime images (∼1 km per pixel) of Lake Chad. The permanent lake waters can be clearly seen in the centre of the southern basin. Inundated marsh, revealed by dark grey hues, can be seen on the January, 1996 image marking the dry (but high Chari River inflow) season.

Image AVHRR (canal 2, résolution de 1 km par pixel) à mi-journée du lac Tchad. Les eaux permanentes du lac sont clairement identifiées dans la partie centrale du bassin sud. Les zones inondées en marge (indiquées en grisé) sont visibles sur l'image prise en janvier 1996, qui correspond à la saison sèche, mais avec un fort débit de la rivière Chari.

Coe and Birkett [12] developed the work of Birkett [8] by using a combination of gauge and radar altimetry data, not only to deduce inflowing river discharge, but also to predict in advance the downstream discharge and lake level. In particular, the prediction of the wet season water height on the lake and marshes was of particular interest because the seasonal maximum level determines the success of the farming and fishing people on the southern shore of the basin [43]. The technique used upstream measurements of surface water height from the TOPEX/Poseidon radar altimeter, calibrated through simple empirical regression techniques with ground-based gauge height and discharge data, to estimate the mean monthly river discharge of the Chari River at N'Djamena, Chad (about 500 km downstream of the altimetric measurements). It also aimed to predict the wet season height of the surface waters within the Lake Chad basin (more than 600 km downstream). In the particular case of the Lake Chad Basin, a calculation of water height directly from satellite height was more instructive than a general analysis of volume change, because the local population of the lake basin is more dependent on lake level fluctuations for their livelihood and because the conversion of lake basin volume changes into water height changes is extremely difficult due to the enormous seasonal fluctuations in the complex marsh area.

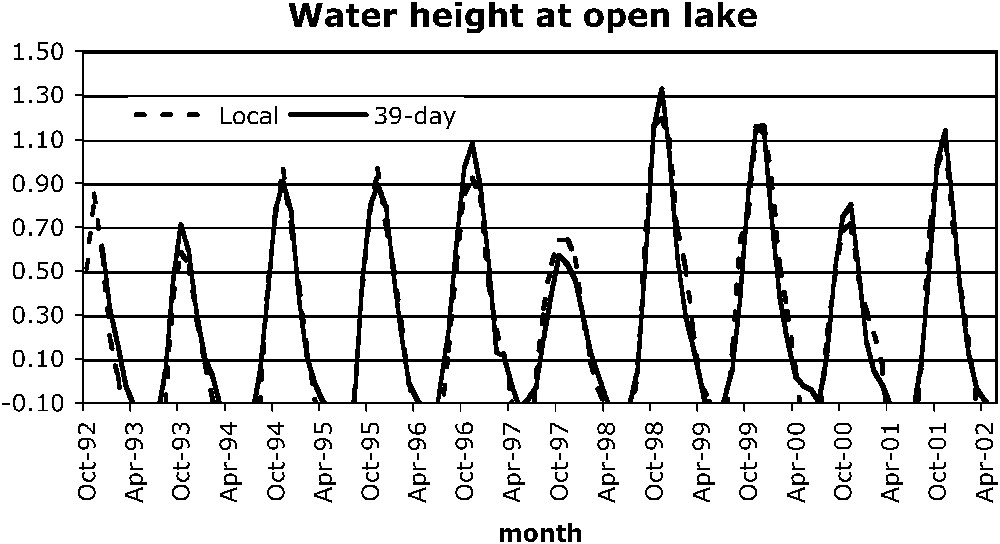

Coe and Birkett [12] found that the altimetric stage measurements, upstream at the Chari/Ohuam confluence could be used to estimate river discharge about 500 km downstream at N'Djamena and do so 10-day in advance (). Via simple linear correlation methods, the stage measurements were also used to estimate the height of the permanent waters of the lake (600-km downstream) 39 days in advance (, Fig. 14). Predicting the water height on the western marshes of the lake-bed though was poorer (), due to a change in response time of the local stage to the seasonal floods. This change may be due to a variation in the hydraulic connectivity of the marshes with the open lake, which coincides with an observed increase in mean water level in the latter half of the 1990s.

Comparison of observed versus predicted water height for the open lake region. The observed (local) height is obtained directly from the T/P radar altimeter observations. The predicted height (with 39-day phase lag) is obtained via observation and correlation of water heights at the Chari location (from [12]).

Comparaison des hauteurs prédites et observées pour les eaux permanentes du lac. Les données observées (locales) de hauteur sont obtenues directement par les observations du radar altimètre de TOPEX/Poseidon. Les hauteurs prédites (déphasées de 39 jours) sont obtenues par corrélation avec les observations faites à Chari (issues de [12]).

The excellent river discharge and lake water predictions show that the altimetry is an additional useful tool where rapid water resource assessment is desirable. In comparison to limited available gauge data, the prediction study found the satellite observations advantageous. Not only the remote sensing data are received continuously, but they are also potentially available to the user within a few days after measurement. This accessibility together with spatial coverage across the basin (i.e. the favourable time-lag between upstream and downstream points) provides an opportunity to predict, as much as 1–2 months in advance, the downstream water resources. Such a general development technique for water resource quantification and prediction from satellite altimetric data may be potentially useful in other regions of the globe.

4 Conclusions

Both lake elevation and storage volume are important parameters for routine monitoring and for studying water balance variations across the catchment basin. Applications can be interdisciplinary, ranging from hazard prediction to environmental and social concerns. Threading through all themes is the influence, control and effect of climate variability. Radar altimetry can contribute to the measurement of lake height variability over the lifetime of the satellite. The measurements can be acquired along the position of the satellite ground track with accuracy of the order of a few centimetres to tens of centimetres rms. Such measurements can be combined with bathymetry and imaging-derived area extent to further deduce changes in storage volume. Case studies of the Aral Sea have shown that estimates of the water mass balance are accurate to ∼3 km3 yr−1, which contributed to solve the issue of underground water flow. For remote lakes, altimetry can be the unique system to determine an accurate water balance.

There are sampling limitations to the technique, but combining datasets from different altimetry missions provides higher temporal and spatial resolution. Compilation of data from the Jason-1 (10-day repeat), GFO (17-day) and ENVISAT (35-day) missions can provide a repeat measurement at a frequency better than a single mission alone. While Jason-1 may only view ∼300 lakes, ENVISAT gains an additional ∼700 targets. Future satellite missions based on a combination of altimetry and interferometry (see [3] for discussions) could provide a promising future for true global lake studies with height and width observation of all targets with centimetre accuracy.