Version française abrégée

Introduction

La position et l’environnement du port romain de Fréjus suscitent, depuis plus de 40 ans, plusieurs points d’interrogation parmi les archéologues et les historiens [1,8–10]. Des opérations archéologiques de sauvetage permettent d’apporter des données nouvelles sur l’environnement littoral de la colonie romaine de Fréjus.

Contexte géomorphologique

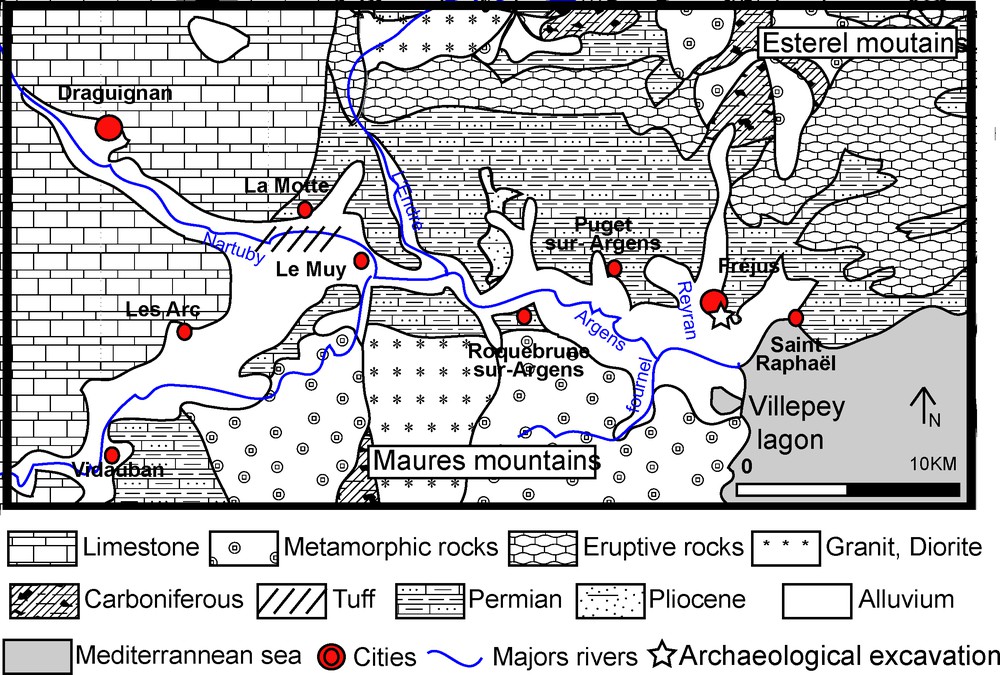

Le fleuve Argens, long de 100 km, traverse les massifs calcaires de Provence, le massif cristallin des Maures, puis la partie occidentale du complexe volcanique de l’Esterel (Fig. 1). La basse vallée correspond à une vaste ria comblée, de 5 km de large et de 11 km de longueur [5,7]. Sous l’effet conjugué du ralentissement de la transgression marine postglaciaire et des forçages climatiques et anthropiques [7,18], les sédiments du prisme de haut niveau ont remblayé la topographie fini-Pléistocène des environs de Roquebrune-sur-Argens à partir de 6000 B.P. cal. [6]. Les mesures du niveau marin holocène révèlent que la région de Giens–Fréjus est très proche du secteur tectoniquement stable de Marseille [13,14,16,17].

Geological sketch of the lower Argens valley.

Fig. 1. Croquis géologique de la basse vallée de l’Argens.

Données géoarchéologiques

Les fouilles du « théâtre d’agglomération » (sous la direction de P. Excoffon) étaient localisées au pied de la butte Saint-Antoine, au sud de la colonie militaire romaine fondée en 49 av. J.-C. (Fig. 1). Les tranchées, d’une profondeur de 3 m, ont révélé la stratigraphie suivante.

- (A) Le substratum est composé de grès siliclastiques. Il présente une forte pente, entaillée de petites rigoles comblées de sables littoraux. La faune fixée sur le rocher est composée de vermets (Vermetus triqueter) dont la limite supérieure de peuplement a été mesurée à −33 cm ±6 cm N.G.F. Cette limite correspond au zéro marin biologique moyen (limite supérieure de la zone infralittorale [12,13,19]. Les vermets sont enfouis sous des sables littoraux contenant des céramiques homogènes, datées entre les années 30–20 av. J.-C. et 20–30 apr. J.-C. Deux dates AMS 14C calibrées [20,21], mesurées sur les vermets, ont donné comme résultat : 300 av. J.-C.–10 apr. J-C. et 160 av. J-C.–80 apr. J.-C. (Poz-14371, 2420 ± 30 yr B.P. et Poz-14372, 2420 ± 30 yr B.P.).

- (B) Durant la seconde moitié du 1e siècle av. J.-C. les apports détritiques de l’Argens transforment la nature, la morphologie et les dynamiques du littoral. Le pied de la butte Saint-Antoine est alors enfoui sous 1,5 m de sables côtiers, bien triés et lités. Le faciès et le pendage de ces couches indiquent la présence d’un cordon exposé au déferlement. Ces plages progradent de 200 m en deux siècles vers le sud. Le sommet de la stratigraphie est composé de sables limoneux ocre, révélateurs d’une sédimentation terrigène en milieu émergé.

Paléogéographie de la basse vallée de l’Argens

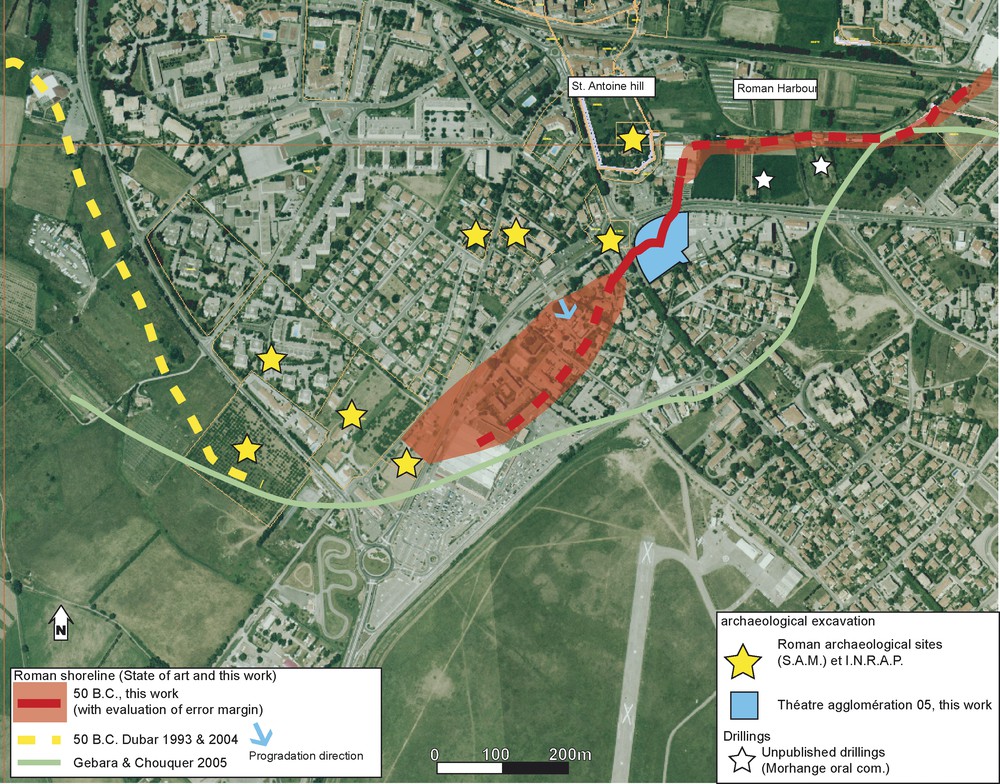

La précision des données acquises permet de dater et localiser le rivage romain de Fréjus, apportant quelques réponses au débat de la connexion entre le bassin portuaire romain et son environnement [1,11,15,20,22]. Ainsi, les murs-quais fermant le bassin baignaient dans la mer lors de leur construction, tandis qu’aucune plaine littorale ne séparait la ville antique du rivage vers le sud (Fig. 4), comme il est encore couramment admis [20]. Le pendage des plages progradantes traduit des apports fluviaux massifs liés à l’avancée du front deltaïque de l’Argens [25].

Proposed Roman shoreline and ancient hypotheses.

Fig. 4. Proposition de localisation de la ligne de rivage romaine et anciennes hypothèses.

La comparaison avec d’autres données acquises dans la partie occidentale de la vallée, près des étangs de Villepey [4], montre une dissymétrie du trait de côte durant la période romaine, le cordon littoral étant plus avancé sur la partie sud-est de la vallée durant les périodes historiques. Les apports sédimentaires du Reyran peuvent expliquer ce phénomène.

Conclusion

Les nouvelles données acquises dans la vallée de l’Argens permettent de préciser la paléogéographie de la colonie militaire de Fréjus et les processus de mutation des environnements de la ria. Toutefois, la précision des résultats est encore hétérogène et cette recherche doit être complétée par de nouvelles études sédimentologiques et une modélisation numérique [6].

1 Introduction

For more than 40 years, scholars [1,8–10] have been involved in relocating the environment of the ancient harbour of Forum Julii on the coastal margin of the Argens valley. In August 2005, a multidisciplinary team comprising archaeologists and geomorphologists discovered a buried palaeo-cliff dated ca. 50 B.C. under the present flood plain of the Argens River. Here we present new geoscience data elucidating the coastal palaeogeography of the Argens ria since the first century B.C., and its implications for future geoarchaeological research in Forum Julii and the surrounding coastal plain.

2 Geomorphological context

The Argens River is a medium-sized watershed of 100-km length. The waterway's headwaters lie in Middle Provence. The river lies in a Permian depression overlooked by the crystalline mountains of the Maures to the east/west and the volcanic hills of the Esterel to the west/east (Fig. 1). The lower valley is a large silted ria, 11 km long, whose maximum flooding surface is dated 6000 yr B.P. [5,6]. This mid-Holocene ria terminates inland around the village of Roquebrune-sur-Argens, coeval with the maximum marine ingression [6]. Thick prograding highstand tracts have accumulated downstream from this point, infilling the valley incised during the last glacial lowstand. Progradation is indicated after 6000 yr B.P. until the medieval period at least [6].

Sediment infill of the ria can be attributed to two factors, namely: (1) valley geometry versus relative sea-level changes, and (2) changes in clastic sediment supply influenced by climate forcings and human impacts since Neolithic times [7,18]. The delta's sediment strata yield insights into the hinterland's palaeoenvironmental influence on fluvial liquid and solid discharges. The Argens delta started to form when the rate of sea-level rise decelerated around 6000 B.P., leading to a positive balance between accommodation space and sediment supply. Increasingly, coarser material accumulated in this base-level depocentre, culminating in alluvial and coastal progradation.

During the Holocene, the Argens area has been isostatically stable. For example, Le Notre [14] has shown that there has been no uplift movement on a centennial timescale. At a millennial time scale, relative sea-level data from Giens show the absence of any crustal mobility between the ‘stable’ region of Marseilles and Fréjus [13,16,17].

Holocene pollen delta from the catchment shows widespread forest development between 7000 and 6500 yr B.P. [7,16]. From a mid-Holocene maximum, this forest cover decreased progressively after 6500 B.P. in response to anthropogenic impacts. Significant modifications in forest cover around 3000 B.P. are consistent with human clearances during the Iron Age.

3 Field data

The studied site is located on the southern border of the Saint-Antoine hill, southwest of the Forum Julii Roman town founded in 49 B.C. This emergency excavation, called ‘théâtre d’agglomération’, took place during the summer of 2005 (Fig. 1). Stratigraphic trenches ca. 3 m deep are characterized by the following data.

3.1 Substratum

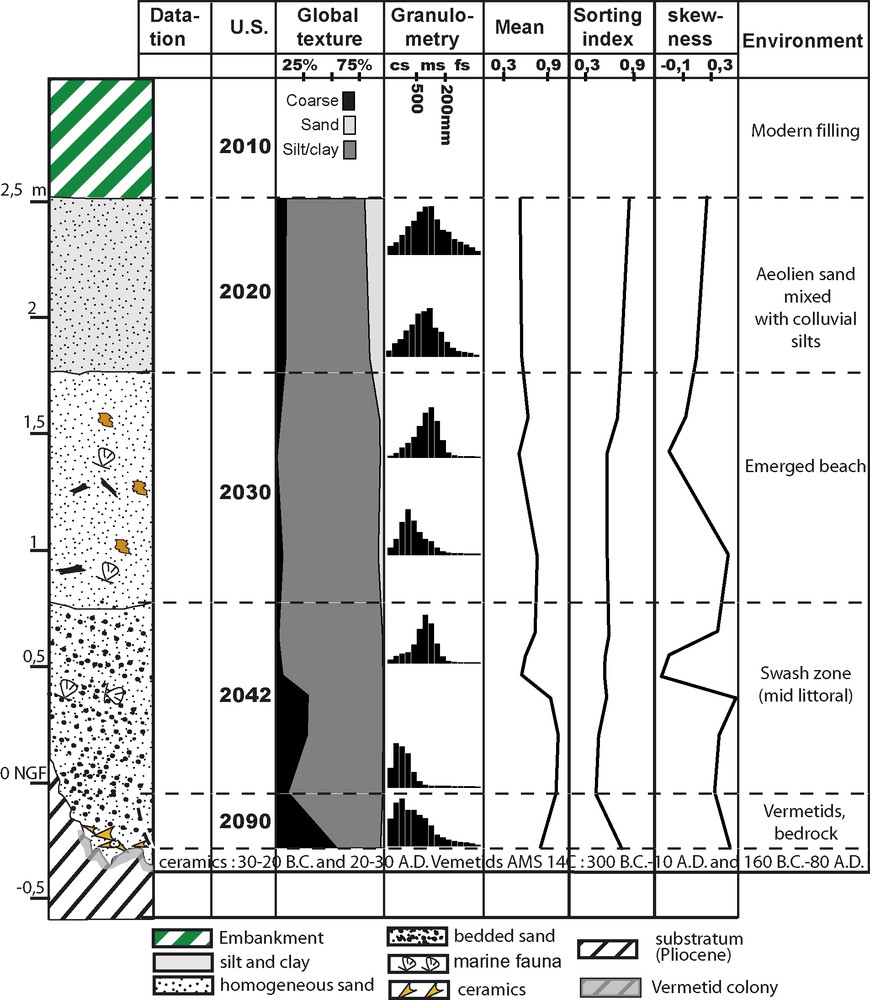

The substratum is composed of siliclastic sandstone with in situ fixed fauna and small gullies infilled with sand deposits (Fig. 2). The sedimentology is typical of the subtidal and mid-littoral zones. The upper limit of fixed Vermetus triqueter molluscs lies at −33 cm ±6 N.G.F., a limit that corresponds to the biological mean sea level (upper limit of the subtidal zone, [12,13,19]). The altitudinal data was measured by a laser triangulation based on an official IGN topographic reference point (error margin < 3 cm). Two samples were dated by AMS 14C; sample Poz-14371 yielded a radiocarbon age of 2420 ± 30 yr B.P. and sample Poz-14372, 2345 ± 30 yr B.P. The calibrated ages of the two samples are 300 B.C.–10 A.D. and 160 B.C.–80 A.D., taking into account the global marine reservoir age curve [23] and shifts in local delta R [22]. All vermetids were sealed by the prograding beach-ridges, and are accurately dated by ceramics to between 30–20 B.C. and 20–30 A.D., which is coherent with the 14C data. Numerous ceramics were found in the palaeo-coast's micro-gullies. Chronologically, this material is homogeneous. The oldest fragments found during the excavation were: (1) an amphora collar from Marseille (type Dressel 7/11) produced around 30 B.C. [3], (2) fragments of Italic Terra sigilata, and (3) Italic culinary ceramics, in particular an Italic caccabus 3C, which was not produced after the end of the first century B.C. The latter comprises the edge of a micaceous dish from the Fréjus area, which could not be later than 20–30 A.D. [20].

Chronostratigraphy of the ‘théâtre d’agglomération’ archaeological site.

Fig. 2. Chronostratigraphie du site archéologique du « théâtre d’agglomération ».

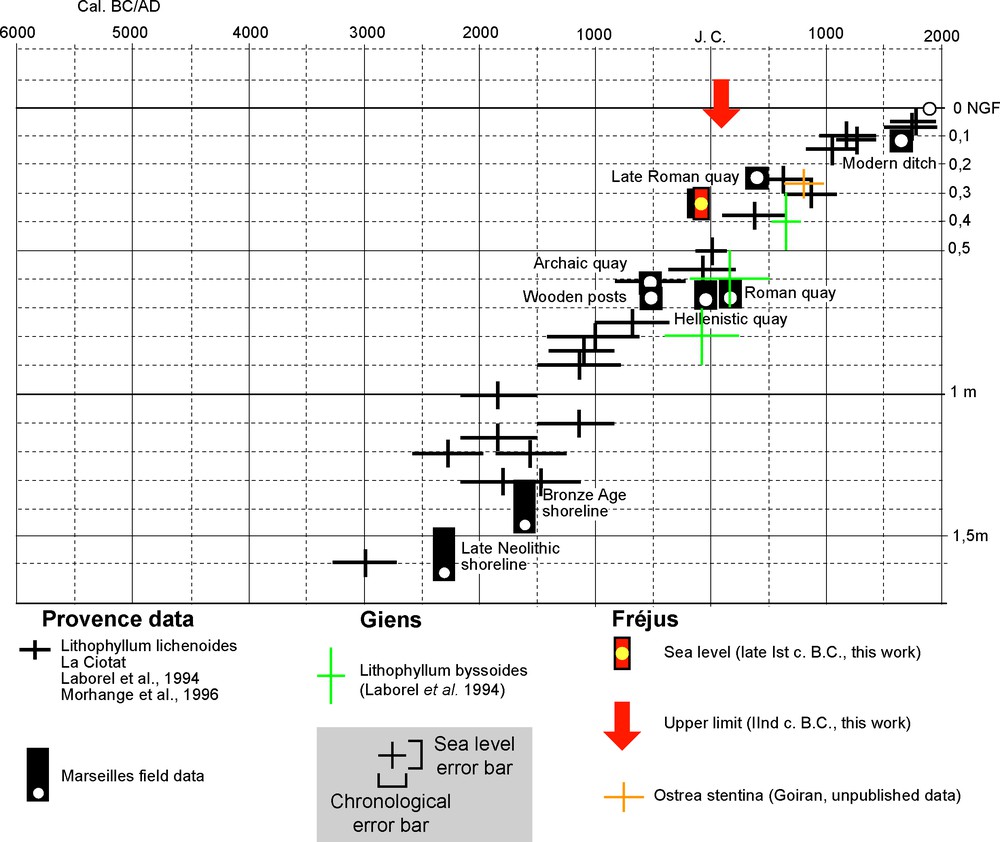

It is important to note that this palaeo-sea level corroborates previous field data. J.-P. Goiran and J.-J. Dufraigne (unpublished data) discovered an upper oyster (Ostrea stentina) limit at −22 cm N.G.F. The error margin is significant for oysters (±25 cm), which grow just above vermetids and are indicative of brackish waters. These shells yielded a radiocarbon age of 1820 ± 30 B.P. (LY-9154), or 548 to 663 cal. A.D. (Fig. 3). Logically, this sea-level index point lies slightly above our data, and is dated to a later period. Laborel et al. [13] reconstructed the relative sea-level history of the nearby Giens peninsula (70 km to the west, on the Maures coastline). The sea-level point discovered in the Agglomeration Theatre is in agreement with the Giens data (Fig. 2). At a regional scale, analogous relative sea-level histories are documented at different sites (Marseilles, La Ciotat, Giens, and Fréjus), and are inferior to the bathymetric error bar (e.g., the Late Holocene crustal mobility is inferior to ca. 10 cm). The relatively high level at Fréjus (Fig. 3) could be explained by its location. On rocky promontories, the wave effect can locally raise the mean biological sea level.

Local and regional sea-level data.

Fig. 3. Données locales et régionales du niveau marin.

Our new data from Fréjus confirm: (a) the absence of any Holocene sea level above the present one along the Provence coast, except in the direct vicinity of the Alps, near Nice [8], and that (b) relative sea-level changes since Roman times have been modest. Their role in coastal deformation is therefore relatively minor in comparison with sedimentary input and morphological characteristics of the Argens’ drowned valley.

3.2 Coastal metamorphosis (rocky versus sandy coasts)

During the second half of the first century B.C., the coastal landscape underwent significant modifications. Important sediment inputs completely transformed the nature and location of the coastline (Fig. 2). For example, more than 1.5 m of well-sorted sand overlies the rocky promontory. These sands comprise homogeneous beds with a strong southern dip (5°). Highly variable mean grain size between the beds is linked to wave exposure and reworking. The stratigraphy therefore concurs with a prograding sand facies system, with a shoreface exposed to energetic wave dynamics. A geomorphological metamorphosis led to transformation of the rocky coast into a deltaic margin characterised by rapidly accreting ridges during the first century B.C. These sediments are typical of the upper subtidal and midlittoral zones (e.g., shoreface and beach deposits). The coastline prograded rapidly southwards, and the sandy deposits buried and fossilised the vermetid colonies.

Sedimentation rates were very high for this natural environment (0.75 cm/yr between the second part of the first century B.C. and the second century A.D.). The sandy shoreline buried the rocky coast and prograded 200 m in ca. two centuries, at an average rate of 1 m/yr. Corresponding macrofaunal assemblages are typical of reworked shoreface sands, with taxa from diverse ecological assemblages.

Finally, the upper part of the stratigraphy is characterised by two facies. The first comprises homogenous sand without any sedimentary structure, while the second is homogeneous silty sand. They point to the transition from a subaqueous environment to an upper beach and a subaerial deltaic plain after the second century A.D.

3.3 Palaeogeographical and geoarchaeological changes

At a local scale, high-resolution analyses of the trench stratigraphy allow us to locate precisely the first century B.C. coastline at the base of Saint-Antoine hill. Since the 19th century, historians have actively debated the landscapes of the ancient Roman basin [1,11,15,21,24]. These results have important geoarchaeological implications in terms of the connection between the ancient Roman harbour and the open sea. Indeed, the southern face of the southern breakwater was washed by seawater when it was built. In light of these data, the topography of ancient Fréjus must be reinterpreted (Fig. 4). Rivet et al.'s [21] coastal reconstruction must be modified, and the southern mole can now be interpreted as a classic breakwater, protecting the Roman basin, which occupied a semi-open lagoon. At the scale of the archaeological site, the position of the shoreline is less accurate, and might fit in with previous research (Fig. 4).

At the ria scale, this study supports present research on the archaeological settlement of the lower Argens valley [2]. It shows that sand spits are mainly driven by fluvial sedimentary inputs, whilst the role of sediment reworking by long-shore drift is relatively minor. This process explains the geometry of the coastal spit, which is best developed longitudinally. The bay of Fréjus was therefore characterised by deltaic frontal progradation during Roman times rather than mid-bay bar mobility [25].

4 Shoreline morphology and comparison with numerical models

An 8-m-deep core, near the Villepey pond, yields more data on the Roman shoreline at the lower valley's scale. The sedimentological and faunal data show the presence of a shallow marine environment between 5800 and 800 yr B.P. cal. at least [4]. These new data also show the dissymmetry of the shoreline during Roman times. Progradation seems to have been faster in the northern part of the valley. Several reasons could affect the geometry of the Holocene shoreline, the first of which is infilling by the Argens’ tributaries, such as the Reyran, which are more important and numerous on the eastern side of the valley. The second one is the marine current, which could promote marine erosion in the southern part of the valley. Henceforth, these kinds of phenomena have to be taken into account in numerical models [6].

5 Conclusion

New data recently acquired in the Fréjus area reveal a high-resolution palaeogeographical reconstruction of the Argens shoreline. Metamorphosis from a rocky coast to a sandy shoreline during Roman times is described. The direction of the reconstructed progradation was unexpected, and it raises the question of the palaeo-shoreline's detailed morphology. These data also show the difficulty in obtaining a precise geography of coastal palaeoenvironments at the ria scale. For this purpose, multidisciplinary data (archaeological excavation and drilling), allied with numerical models, are necessary.

Acknowledgements

M. Pasqualini helped for the archaeological excavation. M. Dubar, N. Marriner, and an anonymous referee significantly improved the manuscript and figures; their help and criticism has been much appreciated.