Version française abrégée

Introduction et cadre géologique

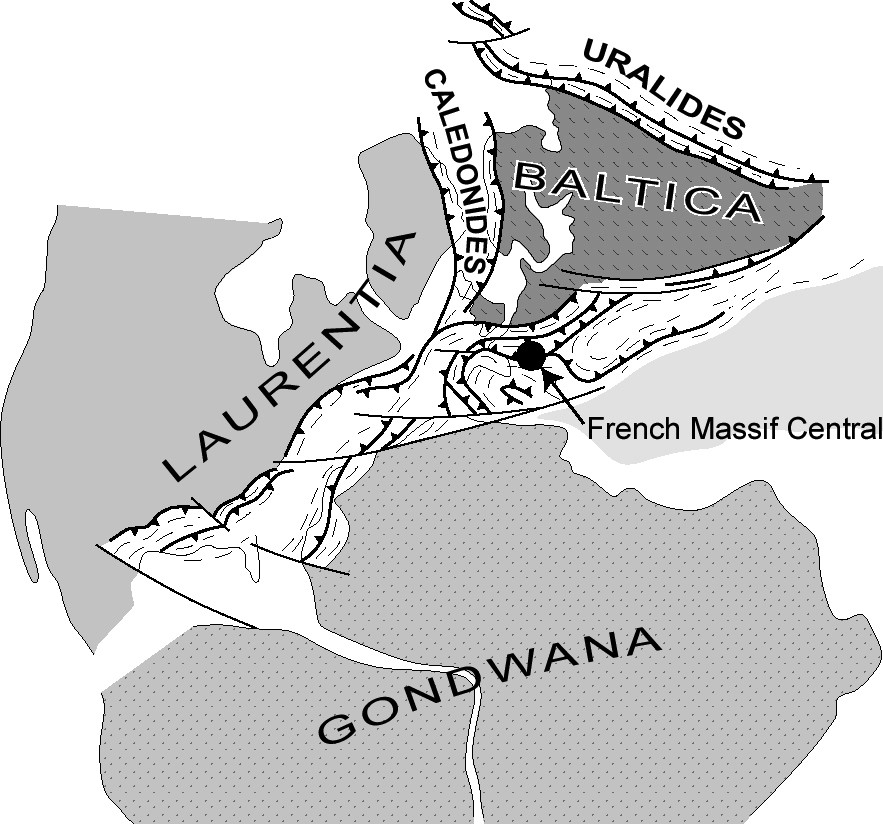

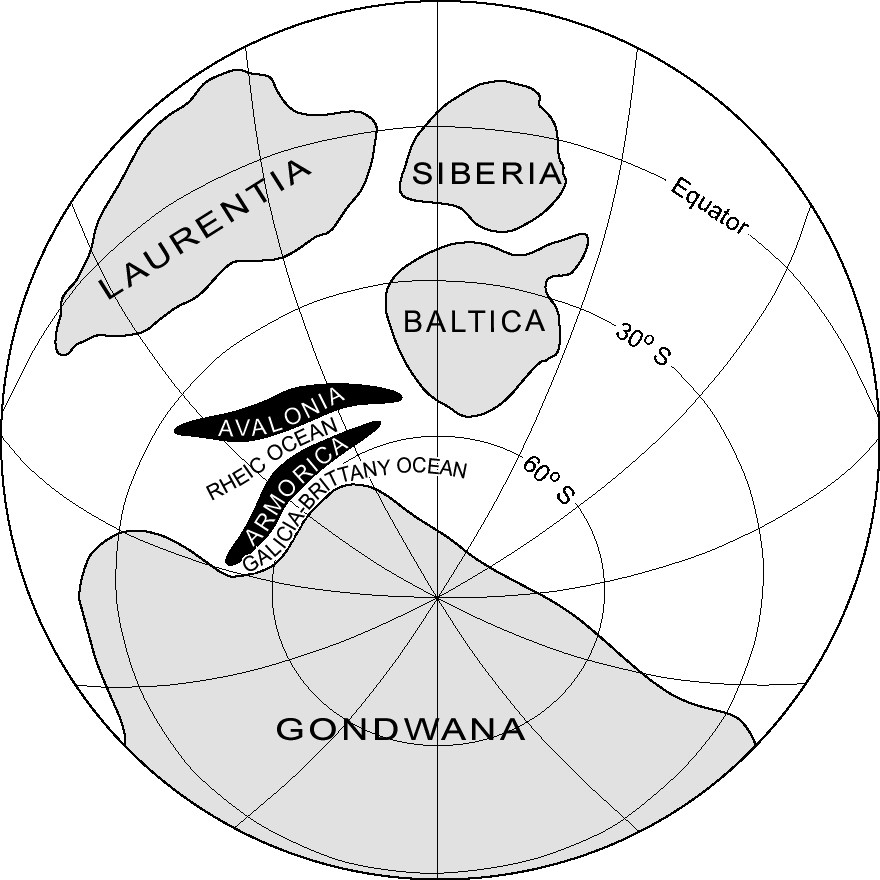

La chaîne Varisque européenne fait partie d’une grande ceinture orogénique, qui s’étend entre le Caucase, à l’est, et les Appalaches, à l’ouest, et est le produit de la collision de deux masses continentales, Gondwana au sud et Laurentia-Baltica au nord (Fig. 1) [18,34]. Entre les deux continents, plusieurs microplaques étaient séparées par des sutures océaniques au Paléozoïque inférieur, avant la collision continentale majeure au Silurien–Dévonien [20]. Le but de cet article est d’améliorer notre connaissance des événements pré-varisques en Europe occidentale, en datant des zircons de l’unité inférieure des gneiss, dans le Massif central. La résistance du zircon à l’altération physique et chimique [14] en fait un minéral particulièrement bien adapté à la datation des protolithes ignés, en particulier en utilisant la microsonde ionique, qui permet d’analyser des domaines relativement petits d’un même cristal.

Position of the French Massif Central in the Variscan Belt between Gondwana in the south and Laurentia–Baltica in the north at ca. 270 Ma (modified from [15]).

Fig. 1. Position du Massif central dans la ceinture Varisque entre le Gondwana au sud et Laurentie–Baltica dans le nord vers 270 Ma (modifié d’après [15]).

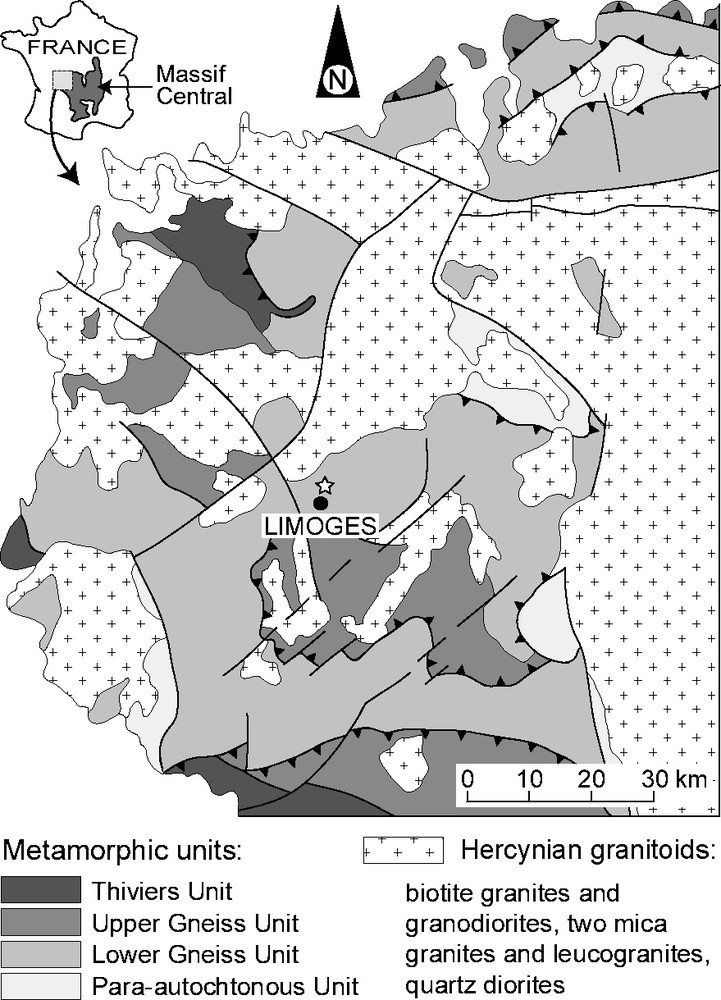

La période pré-Varisque est caractérisée par l’ouverture de domaines océaniques pendant le Cambrien et l’Ordovicien inférieur, associés à un magmatisme bimodal intense [10,19]. Des sutures majeures dans la chaîne Varisque d’Europe occidentale [22] suggèrent la présence de deux petits continents, Armorica et Avalonia, situés près de Gondwana et séparés par l’océan Rhéïque à l’Ordovicien moyen [20]. En France, les océans Rhéïque et Massif central se fermèrent par le biais de deux subductions océaniques de directions opposées [19], entre 450 et 400 Ma [17,24]. La collision continentale principale entre Gondwana et Laurussia vers 400 Ma fut suivie par la mise en place de nappes principales, en conditions de pression moyenne et haute température [24]. Quatre nappes principales ont été décrites [17] : l’unité épizonale supérieure, l’unité supérieure des gneiss, l’unité inférieure des gneiss, et l’unité para-autochtone (Fig. 2). Des intrusions, datées entre 360 et 290 Ma [13], recoupent la plupart de ces unités. Les âges de mise en place des protolithes magmatiques des unités métamorphiques (surtout Rb/Sr sur roche totale) forment deux groupes, 535 ± 12 Ma et 484 ± 14 Ma [2 et références incluses].

Simplified geological map of the northwestern Massif Central, with the main metamorphic units indicated (after [17]). The star represents the position of the sample studied.

Fig. 2. Carte géologique simplifiée du Nord-Ouest du Massif central, avec les principales unités métamorphiques (d’après [17]). L’étoile indique l’échantillon étudié.

Échantillonnage, structure des zircons et résultats analytiques

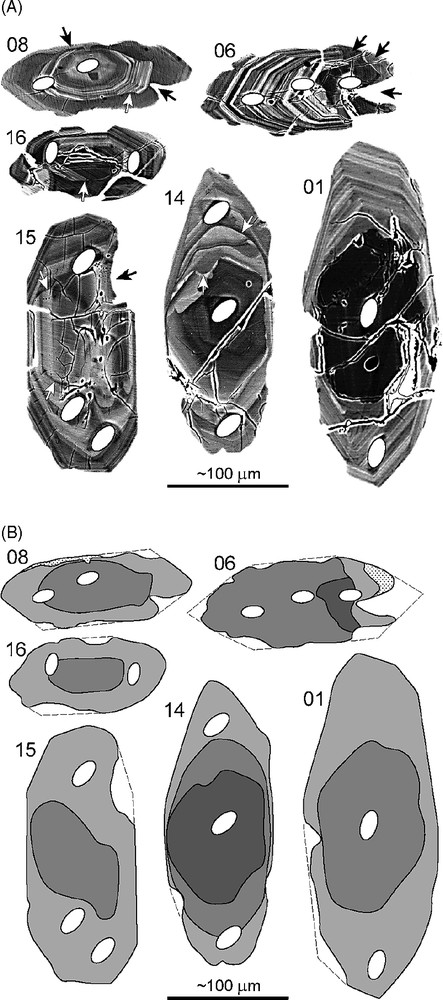

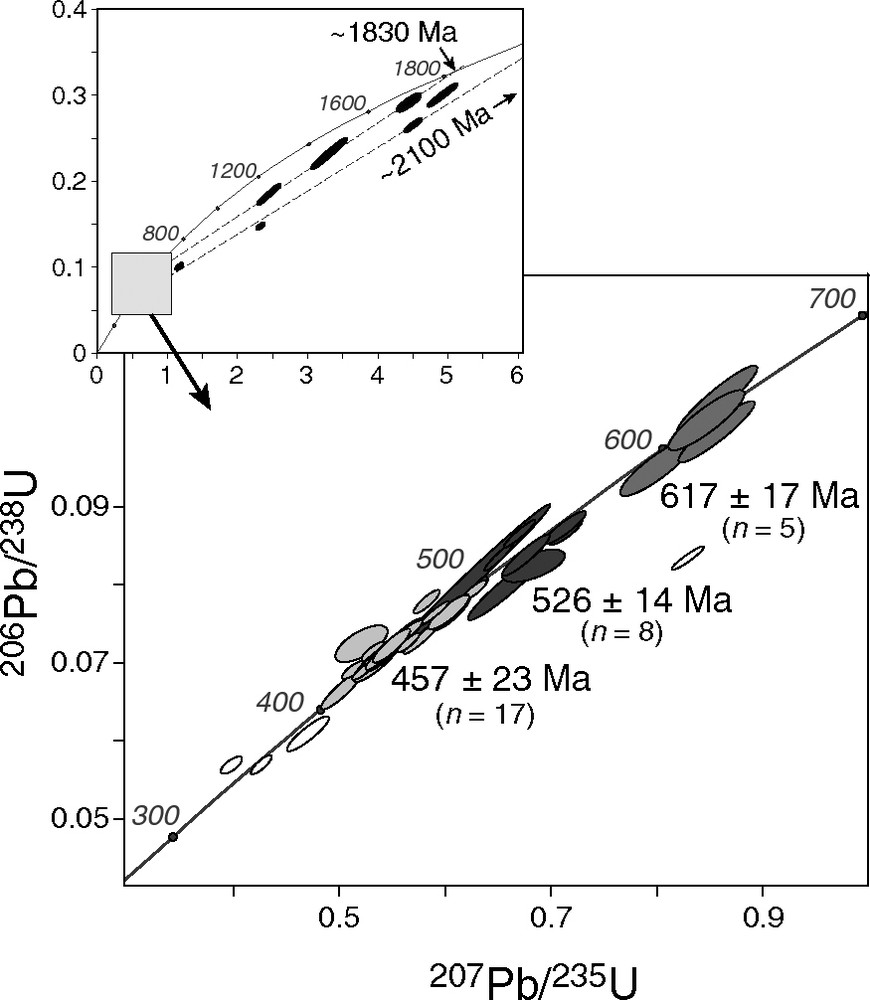

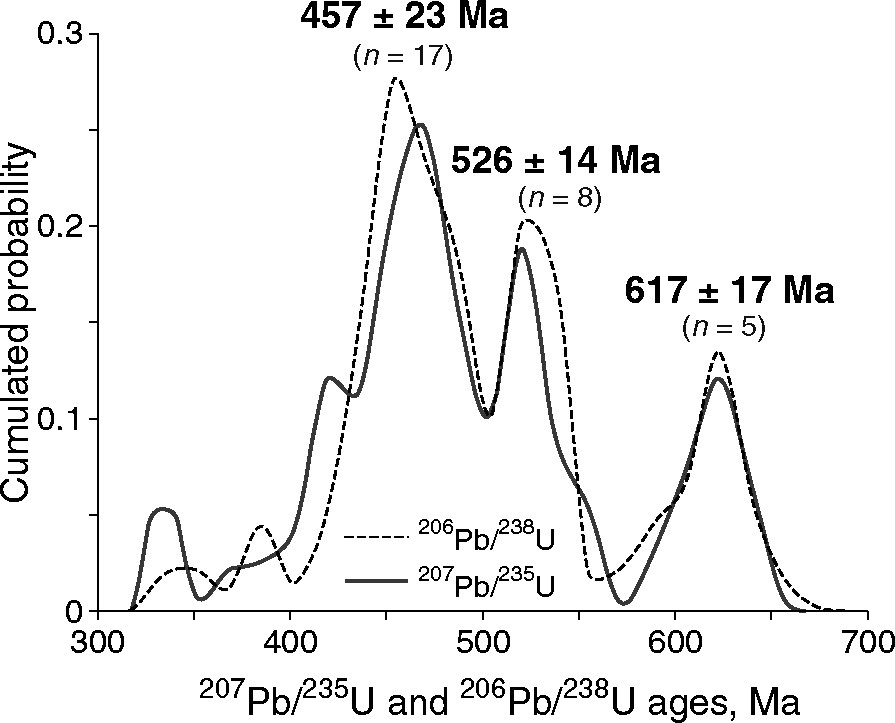

L’échantillon étudié ici provient de l’unité inférieure des gneiss, à quelques kilomètres au nord de Limoges (Fig. 2). C’est un orthogneiss œillé typique (le gneiss de Taurion [17]), composé de quartz, feldspaths, deux micas, avec pour principaux minéraux accessoires monazite, zircon, xénotyme et apatite. Deux faciès du gneiss de Taurion ont été datés à 532 ± 20 Ma et 462 ± 12 Ma (Rb/Sr sur roche totale [12]). Les zircons ont été extraits par les méthodes classiques et analysés à la microsonde ionique au musée d’Histoire naturelle de Stockholm [33]. Les zircons observés en microscopie électronique à balayage (MEB ; électrons rétrodiffusés) montrent des structures internes complexes (Fig. 3), avec des cœurs hérités aux formes irrégulières, au moins deux zones distinctes de surcroissances oscillatoires, séparées par des limites nettes, suggérant des séjours successifs dans des chambres magmatiques [16]. Les surfaces des grains sont souvent corrodées (Fig. 3) et recristallisées, ce qui reflète des conditions métamorphiques [16]. Les âges obtenus varient entre 329 et 1695 Ma (206Pb/238U) et entre 332 et 1799 Ma (207Pb/235U) (Tableau 1) et sont, dans leur majorité, concordants ou subconcordants (Fig. 4). Huit analyses sont situées sur deux discordias mal définies, avec intercepts supérieurs vers 1830 et 2100 Ma (Fig. 4). Les autres analyses forment trois groupes d’âges, visibles aussi dans les diagrammes de probabilité cumulée (Fig. 5), avec des moyennes de 617 ± 17 Ma (2σ ; n = 5), 526 ± 14 Ma (2σ ; n = 8), et 457 ± 23 Ma (2σ ; n = 17) (Figs. 4 et 5).

SEM images (A) and a possible interpretation (B) of typical zircons extracted from the Lower Gneiss Unit in Limousin. The white ellipses correspond to the positions of the primary ion beam. Note the presence of irregularly shaped inherited cores, of multiple zones of oscillatory banding (in grey in (B) separated by rounded and irregular boundaries (white arrows in (A), as well as the effects of metamorphism such as corrosion and in-situ re-crystallisation (black arrows in (A) and dots in (B). See description in text. Masquer

SEM images (A) and a possible interpretation (B) of typical zircons extracted from the Lower Gneiss Unit in Limousin. The white ellipses correspond to the positions of the primary ion beam. Note the presence of irregularly shaped inherited cores, of ... Lire la suite

Fig. 3. Images MEB (A) et leur interprétation possible (B) de zircons typiques de l’unité inférieure des gneiss du Limousin. Les ellipses blanches correspondent à la position du faisceau ionique primaire. À noter la présence de cœurs hérités de forme irrégulière, de zones de croissance oscillatoires multiples (gris en (B)), séparées par des contacts irréguliers (flèches blanches en (A)), ainsi que les effets de métamorphisme, comme corrosion et recristallisation in situ (flèches noires en (A) et points en (B)). Voir le texte pour une description détaillée. Masquer

Fig. 3. Images MEB (A) et leur interprétation possible (B) de zircons typiques de l’unité inférieure des gneiss du Limousin. Les ellipses blanches correspondent à la position du faisceau ionique primaire. À noter la présence de cœurs hérités de forme ... Lire la suite

Results of the U–Th–Pb ion-microprobe analyses of zircons from the Lower Gneiss Unit in the northwestern Massif Central

Tableau 1 Résultats des analyses U–Th–Pb à la microsonde ionique de zircons de l’unité inférieure des gneiss, dans le Nord-Ouest du Massif central

| Concentrations, ppm | Corrected ratios | Calculated ages, Ma | ||||||||||||||

| Grain | U | Pb | Th | 206 Pb/204 Pb | 207 Pb/206 Pb | ±2σ | 206 Pb/238 U | ±2σ | 207 Pb/235 U | ±2σ | 207 Pb/206 Pb | ±2σ | 206 Pb/238 U | ±2σ | 207 Pb/235 U | ±2σ |

| 1 | 532 | 48 | 46 | 4190 | 0.0562 | 0.0009 | 0.0830 | 0.0062 | 0.6435 | 0.0484 | 460.6 | 36.3 | 514.2 | 36.8 | 504.5 | 29.9 |

| 1 | 628 | 52 | 51 | 700 | 0.0523 | 0.0035 | 0.0726 | 0.0019 | 0.5240 | 0.0209 | 300.6 | 150.8 | 451.8 | 11.5 | 427.8 | 13.9 |

| 2 | 1330 | 85 | 76 | 340 | 0.0536 | 0.0013 | 0.0524 | 0.0007 | 0.3870 | 0.0053 | 353.6 | 54.1 | 329.1 | 4.1 | 332.2 | 3.9 |

| 2 | 741 | 70 | 545 | 2620 | 0.0566 | 0.0006 | 0.0729 | 0.0010 | 0.5684 | 0.0088 | 475.1 | 23.2 | 453.4 | 6.3 | 457.0 | 5.7 |

| 3 | 502 | 34 | 70 | 1510 | 0.0562 | 0.0020 | 0.0610 | 0.0017 | 0.4734 | 0.0153 | 462.0 | 79.2 | 382.0 | 10.5 | 393.6 | 10.6 |

| 3 | 655 | 51 | 123 | 6490 | 0.0553 | 0.0012 | 0.0701 | 0.0019 | 0.5350 | 0.0174 | 426.1 | 49.8 | 436.9 | 11.6 | 435.2 | 11.5 |

| 5 | 545 | 43 | 192 | 2130 | 0.0549 | 0.0015 | 0.0665 | 0.0019 | 0.5033 | 0.0158 | 407.6 | 61.5 | 415.1 | 11.4 | 413.9 | 10.7 |

| 5 | 1927 | 202 | 1618 | 980 | 0.0575 | 0.0012 | 0.0766 | 0.0018 | 0.6077 | 0.0157 | 511.4 | 47.5 | 476.0 | 10.9 | 482.1 | 9.9 |

| 6 | 1004 | 135 | 770 | 1250 | 0.0622 | 0.0017 | 0.0999 | 0.0032 | 0.8575 | 0.0302 | 682.4 | 56.8 | 613.9 | 19.0 | 628.8 | 16.5 |

| 6 | 1672 | 181 | 208 | 240 | 0.0601 | 0.0055 | 0.0826 | 0.0018 | 0.6843 | 0.0241 | 606.0 | 197.7 | 511.7 | 10.5 | 529.3 | 14.6 |

| 6 | 699 | 92 | 437 | 6930 | 0.0598 | 0.0010 | 0.1040 | 0.0035 | 0.8573 | 0.0313 | 596.6 | 36.6 | 637.6 | 20.7 | 628.6 | 17.1 |

| 7 | 559 | 63 | 61 | 25040 | 0.0822 | 0.0009 | 0.1011 | 0.0018 | 1.1461 | 0.0230 | 1250.5 | 20.5 | 620.9 | 10.3 | 775.4 | 10.9 |

| 7 | 857 | 80 | 88 | 1800 | 0.0565 | 0.0007 | 0.0838 | 0.0016 | 0.6526 | 0.0126 | 471.8 | 26.3 | 518.6 | 9.2 | 510.1 | 7.8 |

| 7 | 165 | 56 | 3 | 32430 | 0.1177 | 0.0007 | 0.3007 | 0.0105 | 4.8800 | 0.1725 | 1921.4 | 10.2 | 1695.0 | 52.0 | 1798.8 | 29.8 |

| 8 | 307 | 42 | 372 | 0.0610 | 0.0011 | 0.0952 | 0.0029 | 0.8006 | 0.0288 | 639.2 | 39.9 | 586.2 | 17.3 | 597.2 | 16.2 | |

| 8 | 387 | 44 | 570 | 10990 | 0.0598 | 0.0010 | 0.0798 | 0.0035 | 0.6586 | 0.0298 | 597.8 | 34.7 | 495.0 | 20.6 | 513.7 | 18.2 |

| 11 | 1368 | 96 | 110 | 310 | 0.0509 | 0.0028 | 0.0571 | 0.0008 | 0.4009 | 0.0080 | 237.3 | 127.1 | 357.9 | 4.9 | 342.3 | 5.8 |

| 11 | 387 | 44 | 293 | 2060 | 0.0586 | 0.0009 | 0.0840 | 0.0022 | 0.6781 | 0.0186 | 551.0 | 33.0 | 519.8 | 13.0 | 525.6 | 11.3 |

| 13 | 465 | 42 | 135 | 24310 | 0.0574 | 0.0005 | 0.0795 | 0.0011 | 0.6291 | 0.0096 | 507.4 | 18.5 | 493.0 | 6.3 | 495.5 | 6.0 |

| 13 | 270 | 30 | 154 | 5950 | 0.0592 | 0.0007 | 0.0876 | 0.0017 | 0.7147 | 0.0156 | 573.3 | 27.3 | 541.4 | 10.2 | 547.5 | 9.2 |

| 13 | 350 | 31 | 104 | 3690 | 0.0543 | 0.0008 | 0.0781 | 0.0012 | 0.5847 | 0.0104 | 384.0 | 31.6 | 484.7 | 7.3 | 467.5 | 6.7 |

| 14 | 449 | 38 | 42 | 6630 | 0.0561 | 0.0006 | 0.0766 | 0.0011 | 0.5927 | 0.0097 | 457.5 | 21.9 | 475.7 | 6.7 | 472.6 | 6.2 |

| 14 | 99 | 13 | 70 | 9410 | 0.0606 | 0.0012 | 0.1014 | 0.0031 | 0.8474 | 0.0296 | 626.5 | 41.7 | 622.3 | 18.3 | 623.2 | 16.3 |

| 14 | 513 | 43 | 36 | 4360 | 0.0572 | 0.0006 | 0.0772 | 0.0013 | 0.6089 | 0.0111 | 498.8 | 25.0 | 479.5 | 7.6 | 482.9 | 7.0 |

| 15 | 577 | 49 | 135 | 8050 | 0.0572 | 0.0006 | 0.0745 | 0.0025 | 0.5876 | 0.0201 | 500.0 | 23.4 | 463.1 | 14.9 | 469.3 | 12.9 |

| 15 | 1069 | 102 | 859 | 13630 | 0.0556 | 0.0005 | 0.0724 | 0.0026 | 0.5554 | 0.0205 | 436.8 | 20.6 | 450.8 | 15.7 | 448.5 | 13.4 |

| 15 | 802 | 65 | 55 | 38450 | 0.0565 | 0.0004 | 0.0753 | 0.0012 | 0.5869 | 0.0100 | 472.5 | 15.5 | 468.2 | 7.1 | 468.9 | 6.4 |

| 16 | 787 | 51 | 69 | 890 | 0.0545 | 0.0012 | 0.0571 | 0.0008 | 0.4286 | 0.0075 | 390.5 | 51.2 | 357.8 | 5.2 | 362.2 | 5.3 |

| 16 | 545 | 42 | 85 | 2010 | 0.0549 | 0.0008 | 0.0690 | 0.0009 | 0.5225 | 0.0080 | 410.0 | 33.4 | 430.0 | 5.4 | 426.8 | 5.3 |

| 19 | 622 | 61 | 90 | 1860 | 0.0719 | 0.0007 | 0.0837 | 0.0012 | 0.8298 | 0.0126 | 984.2 | 18.8 | 517.9 | 7.1 | 613.5 | 7.0 |

| 20 | 526 | 41 | 104 | 2630 | 0.0541 | 0.0010 | 0.0694 | 0.0011 | 0.5178 | 0.0101 | 376.9 | 40.1 | 432.3 | 6.4 | 423.7 | 6.8 |

| 20 | 600 | 138 | 325 | 1870 | 0.0945 | 0.0012 | 0.1730 | 0.0079 | 2.2538 | 0.1059 | 1518.2 | 24.9 | 1028.5 | 43.4 | 1198.0 | 33.0 |

| 22 | 885 | 319 | 311 | 5760 | 0.1093 | 0.0015 | 0.2921 | 0.0075 | 4.4041 | 0.1271 | 1788.5 | 25.2 | 1652.1 | 37.3 | 1713.1 | 23.9 |

| 22 | 223 | 61 | 65 | 20710 | 0.1016 | 0.0010 | 0.2332 | 0.0156 | 3.2682 | 0.2208 | 1654.2 | 19.1 | 1351.3 | 81.5 | 1473.5 | 52.6 |

| 22 | 976 | 91 | 60 | 13710 | 0.0562 | 0.0004 | 0.0867 | 0.0015 | 0.6716 | 0.0123 | 459.0 | 15.9 | 536.1 | 8.9 | 521.7 | 7.5 |

| 40 | 533 | 44 | 104 | 4120 | 0.0554 | 0.0007 | 0.0731 | 0.0024 | 0.5582 | 0.0189 | 429.2 | 30.1 | 454.5 | 14.4 | 450.4 | 12.3 |

| 40 | 669 | 56 | 198 | 26240 | 0.0556 | 0.0004 | 0.0733 | 0.0009 | 0.5619 | 0.0078 | 435.0 | 15.1 | 456.3 | 5.5 | 452.8 | 5.1 |

| 41 | 267 | 29 | 271 | 710 | 0.0572 | 0.0019 | 0.0769 | 0.0014 | 0.6058 | 0.0135 | 498.2 | 72.8 | 477.3 | 8.3 | 480.9 | 8.5 |

| 41 | 960 | 92 | 65 | 2820 | 0.0596 | 0.0007 | 0.0870 | 0.0014 | 0.7148 | 0.0130 | 589.9 | 26.4 | 537.5 | 8.4 | 547.6 | 7.7 |

| 42 | 296 | 105 | 227 | 21530 | 0.1217 | 0.0005 | 0.2658 | 0.0055 | 4.4595 | 0.0947 | 1981.0 | 7.2 | 1519.5 | 28.3 | 1723.5 | 17.6 |

| 43 | 1320 | 237 | 86 | 640 | 0.1121 | 0.0008 | 0.1485 | 0.0018 | 2.2954 | 0.0295 | 1834.4 | 13.1 | 892.3 | 9.9 | 1210.9 | 9.1 |

Concordia diagram for the zircons analysed, with the average ages of the three main groups. Inset: discordia lines pointing to inherited Palaeoproterozoic zircon fragments.

Fig. 4. Diagramme concordia pour les zircons analysés et la moyenne des trois principaux groupes d’âges. En cartouche : les discordias indiquant des zones paléoprotérozoïques héritées.

Cumulated probability diagram for the 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U ages, based on all individual analyses and their error margins. The three main age groups are clearly visible in both isotopic pairs.

Fig. 5. Diagrammes de probabilité cumulée pour les âges 206Pb/238U et 207Pb/235U, basés sur les âges individuels et leur marge d’erreur. Les trois principaux groupes d’âges sont clairement visibles dans les deux systèmes.

Signification des âges obtenus pour l’évolution tectonique pré-varisque

Les âges paléoprotérozoïques de 1,8 et 2,1 Ga correspondent à des cœurs hérités de zircons (Fig. 3) et sont très similaires à ceux observés dans le Massif central [1,9], et ailleurs dans la chaîne Varisque [5] ; ils reflètent le recyclage de matériel birrimien de l’Ouest africain [4]. Les âges néoprotérozoïques et paléozoïques concordants et subconcordants, obtenus sur des domaines à zonation oscillatoire (Figs. 3 et 4), correspondent à l’âge des protolithes granitiques des gneiss. Il est important d’observer que des âges différents ont été souvent obtenus sur le même grain (Tableau 1), ce qui suggère que les zircons analysés se sont trouvés au moins deux fois en conditions de production de magma, possiblement en contexte de magmatisme intraplaque en environnement géodynamique en extension [23,25]. Ces mêmes événements magmatiques ont, par ailleurs, probablement affecté les microcontinents au nord de Gondwana [11,19], ce qui souligne le caractère cyclique du tectonisme pré-varisque en Europe occidentale. De ce point de vue et en suivant la reconstruction de Stampfli et al. [30], les zircons datés ici proviennent (en excluant les cœurs paléoprotérozoïques) de l’orogenèse cadomienne (correspondant à l’âge de 617 ± 17 Ma ; voir aussi [11]), et ont été ensuite repris lors de la mise en place de corps granitiques dans des blocs issus de Gondwana (l’âge de 526 ± 14 Ma et possiblement l’âge de 457 ± 23 Ma). Une reconstruction plus détaillée serait trop spéculative, mais ce scénario souligne la complexité et le dynamisme de la marge nord de Gondwana au Cambrien et l’Ordovicien. Les événements métamorphiques liés à la mise en place des nappes au Dévonien inférieur [17] ne sont pas observés dans les âges obtenus, puisque les structures correspondantes dans les zircons sont trop fines pour être datées (Fig. 3). Les trois âges entre 350 et 400 Ma (Figs. 4 et 5) pourraient correspondre à l’anatexie tardi-dévonienne, datée à environ 375 Ma [26].

1 Introduction

The Variscan belt of central and western Europe is part of a large mountain belt, extending between the Caucasus in the East to the Appalachians in the West, and resulting from the collision of two continents, Gondwana to the south and Laurentia-Baltica to the north (Fig. 1) [18,31,34]. Between the two main continents, small microplates became separated by oceanic domains and drifted during the Early Palaeozoic before colliding with Laurentia-Baltica prior to the Devonian continental collision [20]. In the French Massif Central, the 420-to-380-Ma collision resulted in a HT/HP, then HT metamorphism [17,18], and was followed by a suite of magmatic events, with ages between 360 and 290 Ma [13]. While the post-collision tectonic events are relatively well understood, as there is direct evidence for their physical conditions and age [26], the pre-Variscan events are sometimes subject to debate [24]. In particular, the age of the individual pre-Variscan events is often obscured by subsequent events, the physical conditions of which provoked partial or full resetting of the isotopic systems in most minerals. The present work aims to advance our knowledge in this domain, by dating zircons contained in the Lower Gneiss Unit in the French Massif Central. Its particularly high resistance to physical and chemical alteration [14] makes zircon a particularly suitable mineral for protolith dating, in particular when the ion-probe method is used, which permits the analysis of relatively small individual domains within the same zircon crystal.

2 Geological setting

The pre-Variscan period is characterised by the opening of oceanic domains during the Cambrian and Early Ordovician, with which is associated an intense bi-modal (tholeiitic and calc-alkaline) and basic to ultra-basic magmatism [10,19,23,25]. Major suture zones in the western European Variscan chain, underlined by eclogites with MORB affinities [22], suggest the presence of two small continents, Avalonia and Armorica, situated close to Gondwana and separated by the Rheic Ocean in Middle Ordovician times [20]. In the French Variscides, the Rheic and Massif Central Oceans were closed through two ocean crust subductions of opposite directions [19] between 450 and 400 Ma [17], closing the ocean domains and responsible for the development of HP metamorphism [24]. The main continental collision between Gondwana and Laurussia occurred at ca. 400 Ma [24], and was followed by the emplacement of the main nappes in conditions of moderate pressure/high temperature metamorphism [24 and references therein]. Four main nappes have been described in the western Massif Central [17] (Fig. 2): (1) the Upper Epizonal Units, represented in the western Massif Central by the Thiviers Unit and situated in the green schist–lower amphibolite facies; (2) the Upper Gneiss Unit, mostly Barrovian metasedimentary (metapelites and meta-greywacke) and metacrystalline (metagranites and metabasalts) lithologies, with high-pressure remnants; (3) the Lower Gneiss Unit, predominantly metasedimentary, with rare gneisses; and (4) the Para-autochthonous Unit, comprised mostly of mica schists with quartzite, meta-greywacke, and rare orthogneiss bands. All of these metamorphic units are intruded by granitoids between ca. 360 Ma and ca. 290 Ma [28]. Several ages are available for the metamorphic units in the French Massif Central, the majority obtained by Rb/Sr whole-rock dating and a few by U/Pb zircon dating. A synthesis of Cambrian–Ordovician ages here reveals the presence of two age groups, 535 ± 12 Ma and 484 ± 14 Ma [2 and references therein].

3 Sampling, zircon structures, and analytical results

The sample studied comes from a borehole situated a few kilometres to the north of Limoges (Fig. 2) and is a typical banded augen-gneiss from the Lower Gneiss Unit, known as the Thaurion Orthogneiss [17]. Previous dating of the Thaurion metagranite gave ages of 532 ± 20 Ma and 462 ± 12 Ma (whole rock Rb/Sr [12]), and 328 ± 6 Ma (biotite K/Ar, Cheilletz, personal communication). It comprises quartz, potassic feldspar, plagioclase, biotite, and muscovite, with accessory monazite, zircon, xenotime, and apatite. After crushing and sieving, zircons were extracted following the classical procedure of heavy liquids and magnetic separation, followed by handpicking under the binocular microscope. More than 50 zircon grains were mounted in epoxy together with the standard zircon 91500 (1065 Ma [32]), polished, and coated with a ca. 30-nm gold film prior to analysis. The zircons are typically small (100 to 200 μm), shaped in stubby prisms with pyramidal tips with length/width ratio of ca. 2.5.

When examined in back-scattered electrons using the scanning electron microscope (SEM), they exhibit complex internal structure (Fig. 3), often consisting of an irregularly shaped inherited central core, a suite of oscillatory banding overgrowths, and surface corrosion and wearing. The distinct oscillatory zonations domains (e.g., grains 8, 14, and 15; Fig. 3), divided by curved and irregular boundaries, are indicative of consecutive stages of growths in a magmatic chamber, separated by periods of partial zircon destruction [16]. Furthermore, the edges of the grains are often corroded (e.g., grains 6, 8, 15, and 16; Fig. 3) or present thin layers crosscutting the oscillatory zoning (e.g., grains 6 and 8; Fig. 3), suggesting metamorphic conditions resulting in loss or re-deposition of zircon material. The SEM observation of the zircons dated (Fig. 3) indicates the succession of several events: initial crystallisation (inherited cores), partial re-melting of the host-rock and residence in a magmatic chamber at least twice (distinct individual oscillatory zones), then metamorphism (corrosion and in situ re-crystallisation [16]).

U–Th–Pb analyses of zircons were performed using a Cameca IMS1270 ion microprobe located at the Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm (Nordsim facility). Analytical procedures are described in detail by Whitehouse et al. [33]. Forty-one analyses were performed on the best 18 crystals (Table 1), with one standard analysis intercalated between every three sample analyses. The results are given in Table 1 and Fig. 3. The 206Pb/238U ages vary from 329 to 1695 Ma and the 207Pb/235U ages from 332 to 1799 Ma (Table 1). Eight analyses are strongly discordant, situated along two insufficiently well-defined discordia lines with upper intercepts of ca. 1830 and ca. 2100 Ma, and lower intercepts of ca. 615 and ca. 543 Ma, respectively (Fig. 4). All other results are concordant to sub-concordant (Fig. 4). The cumulative probability plots of the 206Pb/238U and 207Pb/235U ages indicate the presence of three distinct and well-defined age groups for the period 700–400 Ma (Fig. 5). The average ages are 617 ± 17 Ma (2σ; n = 5), 526 ± 14 Ma (2σ; n = 8), and 457 ± 23 Ma (2σ; n = 17) (Figs. 4 and 5). Interestingly, the lower intercepts of the two discordia lines are ca. 615 and 543 Ma, very close to two of those average ages. Three analyses give ages lower than 400 Ma and do not form a particular age group (Fig. 4).

4 Significance of the ages obtained for the pre-Variscan tectonic evolution

The upper intercept Palaeoproterozoic ages (1.8 and 2.1 Ga; Fig. 3) are similar to ages of inherited component documented in the Massif Central [1,9] and elsewhere in the Variscan Belt [5,7]. These ages are obtained in the inherited cores of the grains analysed and probably indicate the recycling of Birrimian material from West Africa [4]. The concordant and subconcordant Neoproterozoic and Palaeozoic ages, obtained in the oscillatory banding zones of the zircons analysed (Fig. 4), reflect conditions of granitoid magma production. Importantly, distinct ages are often found in the same zircon grain (Table 1), indicating that some of the zircons analysed were involved at least twice in conditions of magma production, resulting in the growth of significant and distinct oscillatory banding zones (Fig. 3). The distinct magma production episodes thus evidenced probably occurred in the context of intraplate magmatism in extensional conditions [23,25]; they likely affected other microcontinents on the northern Gondwana margin as well, as seen in the zircon age of 610 ± 2 Ma, obtained in the Channel Islands [11] and identical to the age of 617 ± 17 Ma from this study, suggesting a similar evolution for other microplates between Laurussia and Gondwana at that time [21,30].

Ages similar to those obtained here have been found throughout the French Massif Central, with two main age groups, Early–Middle Cambrian and Middle Ordovician [2 and references therein, 5 and references therein, 6,13]. That the same ages are found throughout the Massif Central has been interpreted as indicating a similar evolution for separated tectonic blocks according to a Himalayan model [13]. However, the fact that ages belonging to distinct age groups and found elsewhere in the Variscan Belt are seen in a single zircon grain points out to a cyclic evolution of the protolith in a succession of tectonic events also affecting the various microplates between Laurussia and Gondwana. Following the reconstruction of Stampfli et al. [30] and ignoring the inherited Palaeoproterozoic cores, the zircons from the Lower Gneiss Unit in the French Massif Central originated in the Cadomian orogenesis (corresponding to the age of 617 ± 17 Ma), and were subsequently involved in granitoid recycling and reworking in Gondwana-derived basement blocks (the age of 526 ± 14 Ma), followed by granitoid re-working related to the Ordovician ocean crust subduction (the age of 457 ± 23 Ma). It would be difficult to suggest a more detailed sequence of events affecting the protolith of the Lower Gneiss Unit without speculating excessively, but the proposed summary underlines the complexity and dynamism of the northern Gondwana margin in Cambrian and Ordovician times (Fig. 6).

A possible reconstruction of the position of the microplates in the Middle Ordovician. Modified after [19,27,29].

Fig. 6. Une reconstruction possible de la position des microplaques au milieu de l’Ordovicien. Modifié d’après [19,27,29].

The metamorphic events related to the Early Devonian continental collision and the emplacement of the nappes [17] are not well recorded by the ages of the zircons analysed here. The SEM observation reveals that the metamorphic conditions are recorded in the structure of the zircon grains with, in particular, corrosion and in situ re-crystallisation of thin superficial layers, too thin to be analysed, even by the ion microprobe (e.g., grain 8, Fig. 3). Three analyses give ages of ca. 350–400 Ma (Figs. 4 and 5), which would rather correspond to the anatectic conditions of rapid uplift at ca. 375 Ma [26] than to the Early Devonian collision. Finally, the K–Ar age of 328 ± 6 Ma obtained on biotites from the Lower Gneiss Unit (Cheilletz, personal communication) represents Late Variscan exhumation and corresponds well to exhumation ages found in the western Massif Central [3].

5 Conclusions

With the exception of the 617 ± 17 Ma age, the ages obtained in the Lower Gneiss Unit zircons (526 ± 14 and 457 ± 23 Ma) are very similar to those found in the same unit [13] or elsewhere in the western French Massif Central [2]. However, the ages being found in the same zircon grain or population of grains (Table 1) underline the complex pre-Variscan evolution of the oceans and microplates between Gondwana and Laurentia–Baltica during Cambrian–Ordovician times (Fig. 6). It is emphasized that the same zircons were involved consecutively in at least three igneous events, during which new and distinct oscillatory banding domains were formed in a silicate magma chamber [16] (Fig. 3). It is possible that the zircons analysed were not exposed to significant surface alteration in the periods between the igneous events, as the boundaries between the oscillatory banding zones do not seem to indicate important physical weathering [8] (Fig. 3), consistent with the relatively small size of the pre-Variscan microcontinents [21,30].

Comments by Alain Cheilletz1, Michel Cuney2 and Martin Whitchouse3

The results presented in this paper are part of the PhD thesis of Paul Alexandre, defended in Nancy (France) at the ‘Institut national polytechnique de Lorraine’ (INPL) in July 2000, under the supervision of Alain Cheilletz1. The sample analysed in this study, referenced as 98Z1, is located within the Lower Gneiss Unit. It has been selected in the freshest part of a geotechnical drill hole performed in the northern industrial zone of the Limoges city (France) by Pascal Pastier and Michel Cuney2. The U/Pb analytical data were obtained at the joint Nordic ion microprobe facility (NORDSIM) at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, with the assistance of S. Claesson and M. Whitehouse3 during spring 1998; this is NORDSIM contribution No. 186. This study was supported by several scientific grants to Alain Cheilletz and Michel Cuney from the Geofrance 3D program and ANDRA. This is CRPG contribution No. 18604.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful to the two reviewers for their constructive and thorough comments. The analytical support provided by S. Claesson and M. Whitehouse from Nordsim (Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm) is acknowledged. M. Cuney is acknowledged for providing the sample studied. J. Ludden is gratefully acknowledged for providing financial support. The ‘Centre de recherches pétrographiques et géochimiques’ (Nancy, France) is acknowledged for providing logistic support and mineral separation facilities.

1 Nancy University, ENSG–INPL, BP 20, 54501 Vandœuvre-les-Nancy, France; cheille@crpg.cnrs-nancy.fr.

2 Nancy University, UMR G2R CREGU, BP 239, 54506 Vandœuvre-les-Nancy, France; michel.cuney@g2r.uhp-nancy.fr.

3 Swedish Museum of Natural History, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden.

4 Additional reference : E. Deloule, P. Alexandrov, A. Cheilletz, B. Laumonier, P. Barbey, In-situ U–Pb zircon ages for Early Ordovician magmatism in the eastern Pyrenees, France: the Canigou orthogneisses, Int. J. Earth Sci. (Geol. Rundsch.) 91 (2002) 398–405).