Version française abrégée

Introduction

Dans le Nord-Togo, la chaîne panafricaine des Dahomeyides a enregistré quatre épisodes de déformation post-collisionnels, dont résulte une intense fracturation polyphasée. Jusqu’à présent, cette fracturation n’a fait l’objet que de travaux ponctuels [4,7]. Il nous a donc paru utile d’effectuer une analyse systématique du réseau de fractures, dans un secteur où la structure est bien connue, afin d’en confronter les résultats à ceux de l’étude des autres éléments structuraux.

Dans la pile de nappes du Nord-Togo, la tectogenèse panafricaine se décompose en cinq épisodes dénommés Dn, Dn + 1, Dn + 2, Dn + 3 et Dn + 4 [5,34]. À chacun des quatre épisodes post-collisionnels (Dn + 1 à Dn + 4) sont associées des fractures conjuguées. La phase Dn + 1 correspond à l’épisode majeur de structuration des Dahomeyides, avec la mise en place de nombreuses nappes et écailles, entre 608,1 ± 1,2 Ma et 579,4 ± 0,8 Ma [12]. Elle se traduit par la foliation régionale Sn + 1. Les trois phases de déformation post-nappes (Dn + 2, Dn + 3 et Dn + 4) correspondent à des reprises successives de la foliation ou schistosité principale Sn + 1. Il en résulte des plis Pn + 2, centimétriques à métriques et d’axes subméridiens à NE–SW, des antiformes et synformes Pn + 3, hectométriques à kilométriques et d’axes NE–SW, et des virgations Pn + 4, plurikilométriques et d’axes NE–SW à ENE–WSW.

Les images satellitaires et les photographies aériennes

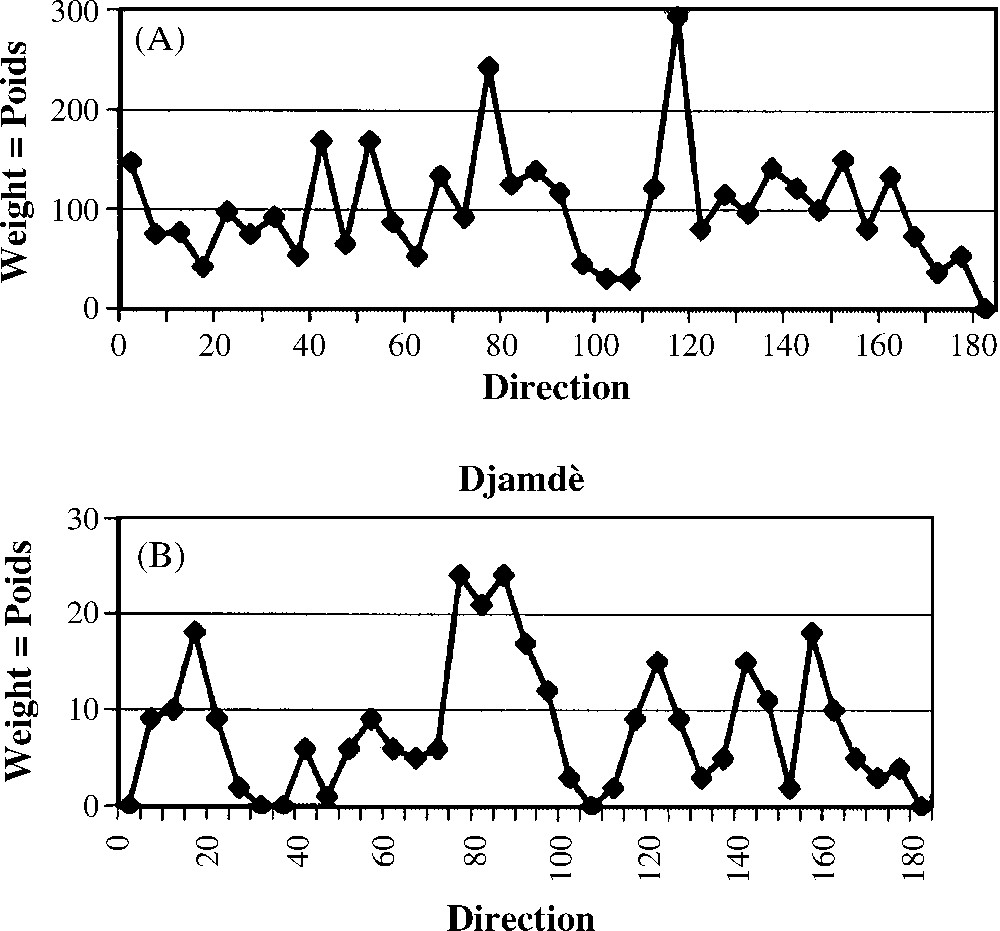

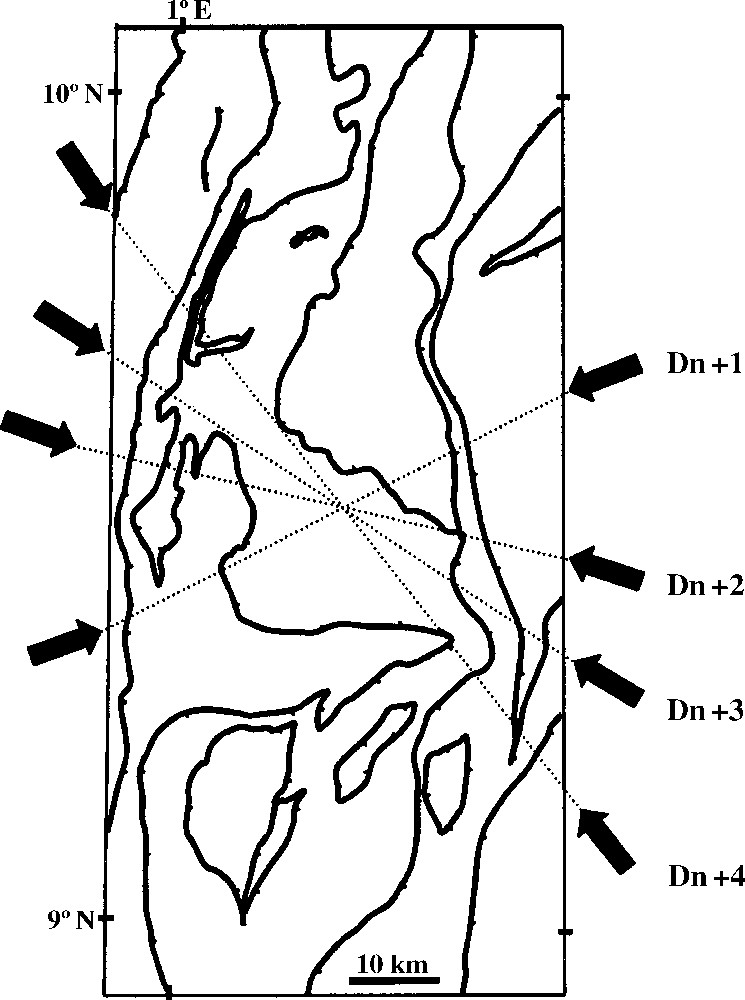

Elles montrent un très dense réseau linéamentaire. Le relevé des linéaments identifiés sur des images satellitaires (Fig. 2) suggère qu’ils résultent de plusieurs épisodes de fracturation superposés. Les directions majeures relevées sont N50, N80, N120 et N150. On y observe de nombreux linéaments plurikilométriques, avec une prévalence des directions N80 et N120 (Fig. 3A). Comme le montre la Fig. 2, ces linéaments sont relativement indépendants des plans de charriage ou de chevauchement qu’ils recoupent fréquemment. L’allure rectiligne de ces linéaments traduit leur caractère subvertical. Il s’agit de fractures ayant valeur de fentes de tension ou de décrochements. Dans le secteur de Djamdè (à l’ouest de Kara), l’étude des fractures reconnues sur des photographies aériennes et sur le terrain permet d’interpréter une partie du diagramme de répartition (Fig. 3B) : les fractures dextres, N75 à N85, et senestres, N135 à N145, sont interprétables comme des décrochements conjugués liés à la phase de déformation Dn + 2 (voir plus bas), alors que les pics N15 et N120 coïncident avec des décrochements conjugués de la phase Dn + 4. L’analyse microtectonique détaillée éclaire ces observations.

Map of kilometric lineaments or fractures statement from the satellite coverage of northern Togo. 1 = Major thrust plane; 2 = strike of main or regional Sn + 1 foliation; 3 = lineament or fracture (K = Kara, A = Aleheride, S = Sokode).

Fig. 2. Carte de relevé des linéaments ou fractures kilométriques à partir de la couverture satellitaire du Nord-Togo. 1 = contact de chevauchement majeur ; 2 = trace de foliation principale ou régionale Sn + 1 ; 3 = fracture (K = Kara, A = Aléhéridè, S = Sokodé).

Diagrams of graphic representation of the distribution of lineaments from satellite image interpretation (A) and aerial photographs covering the Djamde area (B). Weight = accumulated photo-interpreted lineaments or fractures length in a given direction.

Fig. 3. Diagrammes de représentation graphique de la distribution des linéaments de l’interprétation de l’image satellitaire du Nord-Togo (A) et des photographies aériennes couvrant le secteur de Djamdè (B). Poids = longueur cumulée des linéaments ou fractures photo-interprétées dans une direction donnée.

L’analyse microtectonique

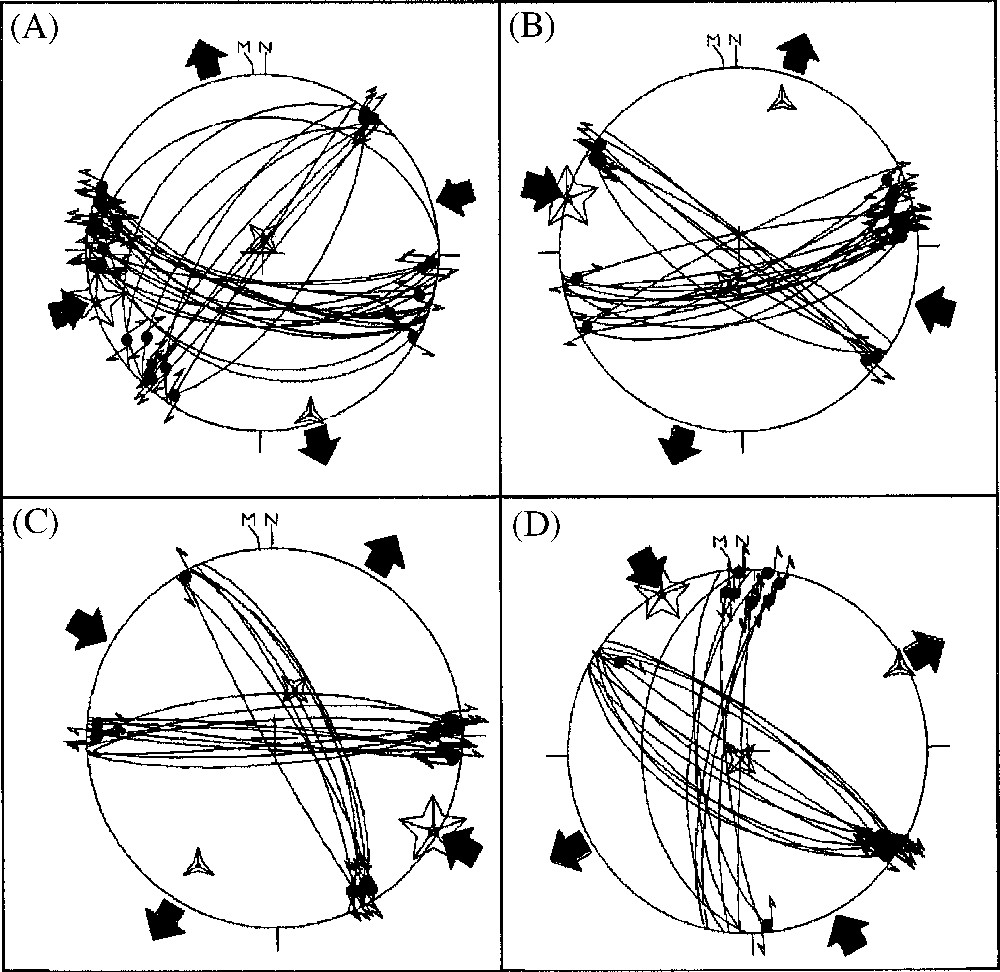

L’analyse microtectonique s’est appuyée sur environ 1500 plans de microdécrochements, étudiés sur 29 sites répartis sur toute la chaîne au Nord-Togo. La chronologie relative entre les différentes familles de fractures a été établie sur le terrain, grâce aux critères de recoupement et de superposition de stries incompatibles [14]. Les données recueillies ont permis de construire une cinquantaine de stéréogrammes. Le traitement des données a été fait par la méthode de J. Angelier [8,9], à l’aide de la version 2000 du programme de calcul des tenseurs de contrainte (R4DT). Cette méthode n’exige que la connaissance des orientations de chaque plan et de sa strie, et du sens du mouvement. La Fig. 4 donne, pour chaque épisode, un exemple des stéréogrammes obtenus.

Examples of stereograms resulting from microtectonic analysis in northern Togo (lower hemisphere projection). (A): Dn + 1 strike-slip microfaults (σ1 N67–02, σ2 N332–66, σ3 N158–04); (B): Dn + 2 strike-slip microfaults (σ1 N288–00, σ2 N197–74, σ3 N18–16); (C): Dn + 3 strike-slip microfaults (σ1 N121–03, σ2 N23–67, σ3 N212–22); (D): Dn + 4 strike-slip microfaults (σ1 N332–01, σ2 N226–87, σ3 N62–02).

Fig. 4. Exemples de stéréogrammes résultant de l’analyse microtectonique au Nord-Togo (projection hémisphère inférieur). (A) Microdécrochements Dn + 1 (σ1 N67–02, σ2 N332–66, σ3 N158–04) ; (B) microdécrochements Dn + 2 (σ1 N288–00, σ2 N197–74, σ3 N18–16) ; (C) microdécrochements Dn + 3 (σ1 N121–03, σ2 N23–67, σ3 N212–22) ; (D) microdécrochements Dn + 4 (σ1 N332–01, σ2 N226–87, σ3 N62–02).

Les microdécrochements Dn + 1

Les familles de fractures attribuables à la phase tangentielle Dn + 1 se distinguent facilement dans les unités externes où la superposition des différentes phases de déformation panafricaine est limitée. Il s’agit des microdécrochements à stries principales nettes, appartenant à une famille dextre, N40 à N50, conjuguée à une famille senestre N100 à N110 (Fig. 4A). Ces microdécrochements définissent le plus souvent une paléocontrainte majeure σ1, ENE–WSW (N65 à N80) et subhorizontale. Dans les nappes frontales ou occidentales du massif Kabyè, les microdécrochements dextres Dn + 1 sont subméridiens à NNE–SSW (N05 à N20), alors que les microdécrochements sénestres sont NE–SW (N60 à N75). On en déduit une paléocontrainte majeure σ1, NE–SW (N40), comparable aux paléocontraintes déterminées dans les quartzites atacoriens de Bafilo et les granulites de Kpaza. La compression Dn + 1 est donc compatible avec de nombreux plans de charriage ou d’écaillage, à valeur de failles inverses, reconnus au Nord-Togo [34]. L’ensemble de la fracturation liée à la phase Dn + 1 suggère un transfert de nappes et un écaillage à vergence WSW.

Les microdécrochements Dn + 2

La phase Dn + 2 correspond à la première déformation post-nappes. Il s’agit d’un serrage discret, dont les microdécrochements sont souvent repris par les fracturations postérieures. Dans les sites internes, ces microdécrochements semblent être du premier ordre. En revanche, dans les sites plus externes, on observe presque exclusivement des fractures de première génération (Dn + 1) recoupées par des fractures Dn + 2. Ces dernières se définissent comme des plans de décrochement, dextres ENE–WSW (N70 à N80) et sénestres NW–SE (N130 à N140), résultant d’une paléocontrainte principale σ1 N100 à N115 (Fig. 4B). Les divers tenseurs de contrainte liés à la déformation Dn + 2 sont homogènes sur l’ensemble du segment de la chaîne au Nord-Togo.

Les microdécrochements Dn + 3 et Dn + 4

Aux fractures Dn + 3 et Dn + 4 appartiennent des plans majeurs, parfois allongés sur plusieurs dizaines de kilomètres (Fig. 2) et structurant les paysages chaotiques des quartzites de l’Atacora. Grâce à quelques superpositions de stries, on parvient à séparer des microdécrochements Dn + 3, sous forme de plans dextres N90 à N100 et de plans sénestres N150 à N165. Ces microdécrochements Dn + 3 résultent d’une compression à paléocontrainte majeure σ1 N120 à N130 (Fig. 4C). C’est dans le chaînon quartzitique d’Aléhéridè que s’observe la meilleure illustration de cette compression Dn + 3. En effet, ce chaînon correspond à un pli hectométrique Pn + 3, légèrement déversé vers le nord-ouest et d’axe subhorizontal (N30–03NE). Ce pli est recoupé par des microdécrochements syn- à tardi-tectoniques, dextres (N95 à N105) et sénestres (N150 à N160). Ces microdécrochements conjugués indiquent des paléocontraintes principales σ1 N124 et σ3 N32, subhorizontales et parfaitement cohérentes avec l’orientation du pli.

Les microdécrochements Dn + 4 sont matérialisés par des plans à tectoglyphes uniformes, sénestres et subméridiens (N170 à N190), ou dextres ESE–WNW à SE–NW (N110 à N130). Ce système de microdécrochements résulte d’une compression à paléocontrainte majeure σ1 généralement N140 à N150 (Fig. 4D).

Discussion

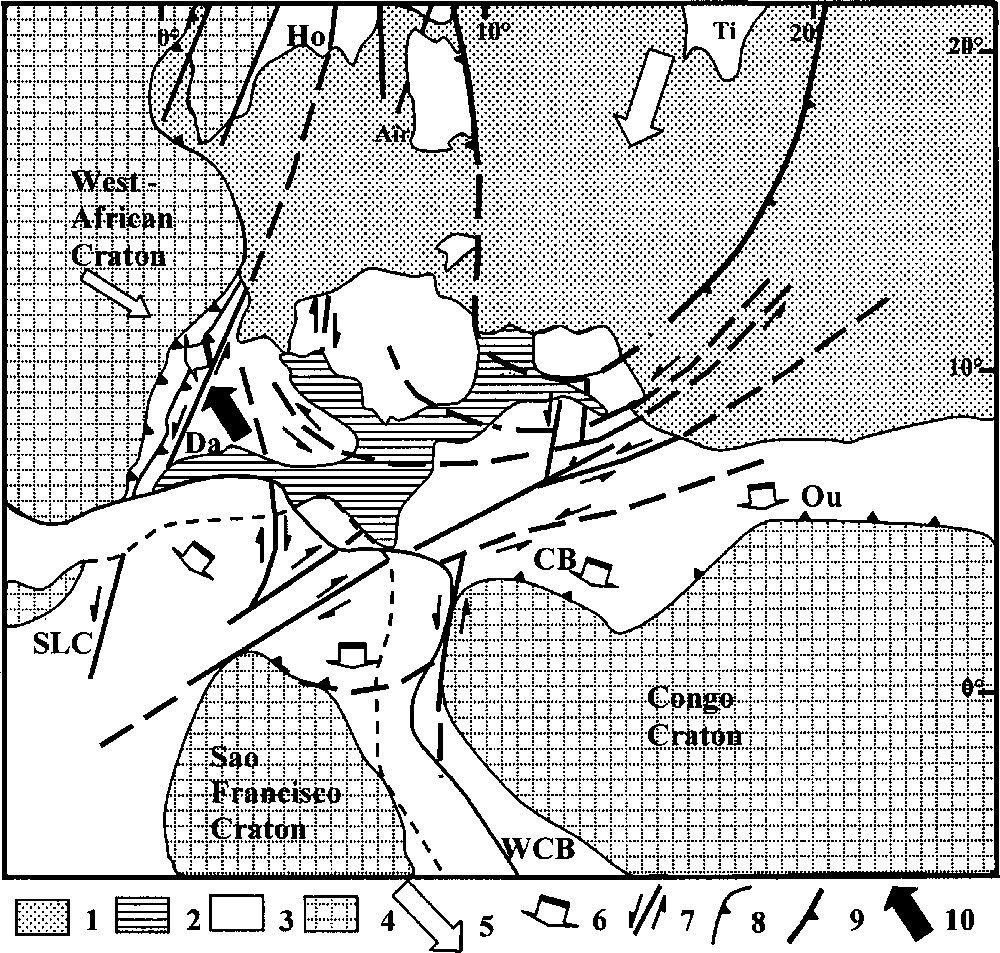

De cette analyse microtectonique ressortent quatre principales directions de compression horizontale, que l’on peut corréler avec les quatre épisodes panafricains de déformation post-collisionnels bien connus et responsables de la plupart des éléments structuraux relevés au Nord-Togo [34]. Par ailleurs, ces directions de paléocontraintes dessinent une rotation horaire, progressive et d’environ 90° (Fig. 5), qui n’était pas connue. Il est à noter que d’éventuels rejeux phanérozoïques des fractures panafricaines ne sont pas pris en compte dans cette analyse.

Evolution of the compressive regime σ1 during the four post-collisional Panafrican phases in northern Togo.

Fig. 5. Évolution du régime compressif σ1 au cours des quatre phases post-collisionnelles panafricaines au Nord-Togo.

À l’échelle de l’orogène trans-saharien, la phase Dn + 2 du Nord-Togo est comparable à la phase D3 définie dans le rameau pharusien et le Hoggar où celle-ci est à l’origine des grandes zones mylonitiques ou de cisaillement subméridiennes [4,13,15,17].

Pour tenter d’expliquer la rotation horaire des paléocontraintes mises en évidence dans le Nord-Togo (Fig. 5), il convient de replacer l’ensemble de la zone mobile trans-saharienne dans le cadre régional du système de poinçonnement de type himalayen, qui a été le moteur de l’édification des chaînes panafricaines d’Afrique centrale et occidentale (Fig. 6). C’est probablement une expulsion de matière vers l’ouest ou le nord-ouest qui est à l’origine de la rotation horaire des paléocontraintes.

Panafrican shear zones device linked to the indentation of the East-Saharan Metacraton (according [24], slightly modified). 1 = Cambrian to Quaternary deposits; 2 = Mesozoic to Cenozoic deposits of the Benoue Graben and the Guinea Gulf Basin; 3 = Panafrican domains (Da, Dahomeyides; Ho, Hoggar; Ou, Oubanguides; CB, Cameroonian Belt; WCB, West-Congolese Belt); 4 = cratonic domains (SLC, Sâo Luis Craton); 5 = direction and sense of convergence and collision; 6 = direction and sense of motion of the Panafrican nappes; 7 = sense of the Late Panafrican motion in the shear zones; 8 = thrust planes; 9 = suture of Aïr-Massenga Ounianga bounding the East-Saharan Metacraton indentation; 10 = direction of the Late Panafrican compression in the Dahomeyide Belt.

Fig. 6. Dispositif de zones de cisaillement panafricaines liées au poinçonnement du métacraton est-saharien d’après [24], légèrement modifié. 1 = Dépôts cambriens à quaternaires ; 2 = dépôts mésozoïques à cénozoïques du fossé de la Bénoué et du bassin du golfe de Guinée ; 3 = domaines panafricains (Da, Dahomeyides ; Ho, Hoggar ; Ou, Oubanguides ; CB, chaîne camerounaise ; WCB, chaîne ouest-congolaise) ; 4 = domaines cratoniques (SLC, craton de Sâo Luis) ; 5 = direction et sens de convergence et de collision ; 6 = direction et sens de déplacement des nappes panafricaines ; 7 = sens de déplacement fini-panafricain dans les zones de cisaillement ; 8 = contact de chevauchement ; 9 = suture de l’Aïr-Massenga Ounianga, délimitant le poinçon du craton est-saharien ; 10 = direction de compression tardi-panafricaine dans les Dahomeyides.

1 Introduction

In northern Togo, the Panafrican Dahomeyide Belt displays four major post-collisional deformation episodes, with four intense brittle deformation phases [2,5,33]. Up to now, this important brittle deformation underwent only brief and local studies [4,7]. Hence, it would be useful to analyze systematically the fault network in an area where the structural characteristics are well known. The results of such analysis may be compared with those from other structural studies. The present paper is based on these results of microtectonic analysis, and it proposes the most reliable correlations.

2 Geological setting

The Panafrican Dahomeyide Belt corresponds to the southwestern part of the Trans-Saharan orogen (Fig. 1). It is of collision type, and it is overthrust directly on the West-African craton (WAC) or on its cover, represented by the Volta Basin. The frontal part of this belt is dominated by important gravimetric anomalies linked to the nappe stacking [23,35]. Its suture zone is materialized by a series of basic to ultrabasic massifs located between the external units, in the West, and the internal ones, in the East. In northern Togo, this belt was recently subject of cartographical, petrological, and structural studies [22,32,34].

Schematic geological map showing the Volta Basin and the Benino-Togolese front of the Dahomeyide Belt (according to [1]), with 1 = Eburnean basement of the Leo-Man shield; 2 = Neoproterozoic cover of the Volta Basin; 3 = gneisso-migmatitic internal and external units; 4 = kyanite- and mica-bearing quartzites; 5 = basic and ultrabasic massifs of the suture zone; 6 = Atacora Structural Unit; 7 = Buem Structural Unit; 8 = Meso-Cenozoic basin of the Guinea Gulf; 9 = overthrusting plane; 10 = mylonitic zone of the Kandi Fault.

Fig. 1. Carte géologique schématique montrant le bassin des Volta et le front bénino-togolais de la chaîne des Dahomeyides (d’après [1]). 1 = socle éburnéen de la dorsale de Léo-Man ; 2 = couverture néoprotérozoïque du bassin des Volta ; 3 = unités gneisso-migmatitiques internes et externes ; 4 = quartzites micacés à disthène ; 5 = massifs basiques et ultrabasiques de la zone de suture ; 6 = unité structurale de l’Atacora ; 7 = unité structurale du Buem ; 8 = bassin méso-cénozoïque du golfe de Guinée ; 9 = contact de charriage ; 10 = zone mylonitique de la faille de Kandi.

The northern Togo is constituted by varied lithostructural assemblages resulting from a collision and a nappe stacking, with vergence to the west. These nappes were structured during four major Panafrican tectonic episodes. The external zone includes nappes and slices of tectono-metamorphic equivalents of the lower and middle megasequences of the Volta Basin [3,33]. The polycyclic basement (2064 ± 90 Ma and 608 ± 17 Ma) is represented in places [5,19]. The basic to ultrabasic granulitic nappes of the Kabye and Kpaza Massifs materialize the suture zone. They took part to the crustal growth due to post-collisional exhumation [6]. Moreover, most of the internal zone units are made up of polycyclic basement rocks such as meta-volcanosedimentary complexes, various gneisses, and migmatites [2,34].

3 Main features of the Panafrican deformation in northern Togo

Within the nappes of northern Togo, the Panafrican tectogenesis is materialized by five kinematic phases defined as Dn, Dn + 1, Dn + 2, Dn + 3 and Dn + 4 [5,34]. Each one of the post-collisional phases (Dn + 1 to Dn + 4) includes at least conjugated faults.

The collision between the WAC passive margin and the Benino-Nigerian plate took place during the Dn phase. The Sn foliation and the granulite or amphibolite metamorphic peak, registered mainly in the internal and suture zones, resulted from this Dn phase.

The Dn + 1 phase corresponds to the major structuring episode of the Dahomeyide Belt, with the setting up of numerous nappes and slices, between 608.1 ± 1,2 and 579.4 ± 0,8 Ma [12]. The Dn + 1 event involves also the oriental part of the lower and middle megasequences of the Volta Basin and develops the regional Sn + 1 foliation.

The three post-nappes kinematic phases (Dn + 2, Dn + 3 and Dn + 4) are successive reworking phases of the main Sn + 1 foliation. They are represented respectively by centimetric to metric Pn + 2 folds, with submeridian to NE–SW axes, hectometric to kilometric Pn + 3 antiforms and synforms, with NE–SW axes, and the multikilometric Pn + 4 virgations, with NE–SW to ENE–WSW axes.

4 The lineamentary network

Satellite images and aerial photographs representing northern Togo display a very dense network of lineaments. The directions of the lineaments identified on satellite images (Fig. 2) suggest that they resulted from several brittle deformation episodes, with four major directions (N50, N80, N120, N150). Many multikilometric lineaments show preferential N80 and N120 directions (Fig. 3A). Moreover, the Fig. 2 indicates that these lineaments are not related to the thrust planes they cut. It also shows that the rectilinear behaviour of these lineaments must be due to their subvertical character. Therefore, these lineaments would be extension or strike-slip faults. Many lineaments of Djamde area (west of Kara, Fig. 3B), well identified on aerial photographs and on the field, are N75 to N85 and N135 to N145 conjugated faults, dextral and sinistral respectively, related to Dn + 2 deformation phase (see below). In addition, the N15 and N120 lineaments coincide with the conjugated strike-slip faults of the Dn + 4 phase.

5 Microtectonic analysis

In northern Togo, about 1500 strike-slip microfault planes were analyzed on 29 outcrops of various rocks (quartzites, gneisses, granulites, and metasilexites). All the planes taken into account display movement markers interpretable with a high confidence degree. The relative chronology between different fault families was established based on crosschecking criteria and superposition of incompatible striae [14]. Most of the study areas of the external zone, such as those of the eastern part of the Buem structural unit, recorded mainly early deformation episodes (Dn + 1 and Dn + 2), whereas the more internal sites, e.g. the quartzites of Atacora, registered mainly late episodes (Dn + 3 and Dn + 4). The available data led us to construct fifty stereograms. Data processing was made by the method of J. Angelier [8,9], with the help of the 2000 version of tensor calculation programs (R4DT). This method requires only the plane and its stria orientations, and the sense of fault movement. The Fig. 4 gives an example of stereograms obtained for each deformation episode.

5.1 The Dn + 1 strike-slip microfaults

The fracture families related to this tangential Dn + 1 phase can be easily distinguished in the external zone, where the superposition of the different Panafrican deformation phases is limited. They are strike-slip microfaults, with sharp main striae, representing a dextral N40 to N50 family conjugated to a sinistral N100 to N110 family (Fig. 4A). These strike-slip microfaults define a major subhorizontal palaeostress σ1 ENE–WSW (N65 to N80). In the frontal or western nappes of the Kabye Massif, dextral Dn + 1 strike-slip microfaults are submeridian to NNE–SSW (N05 to N20), while the sinistral ones are NE–SW (N60 to N75). The major palaeostress σ1 NE–SW (N40), which resulted from this conjugated system, is comparable to those from the Bafilo Atacorian quartzites and the Kpaza granulites.

The whole brittle deformation due to the Dn + 1 phase suggests a nappe and slice transfer towards a WSW direction. Therefore, the Dn + 1 compression is compatible with numerous overthrusting or scaling planes, with reverse fault values, defined in northern Togo [34].

5.2 The Dn + 2 strike-slip microfaults

The Dn + 2 phase corresponds to the first post-nappe deformation. It is a compression event, whose strike-slip microfaults were often reworked during later fracturation episodes. In the internal sites, these strike-slip microfaults seem to be of first order, while in the externalmost sites, the Dn + 1 fractures are generally intersected by the Dn + 2 fractures. These ones are defined as dextral ENE–WSW (N70 to N80) and sinistral NW–SE (N130 to N140) strike-slip planes, corresponding to a major palaeostress σ1 N100 to N115 (Fig. 4B). The Dn + 2 palaeostress tensors are homogeneous within the whole belt segment of northern Togo.

In the kyanite- and sillimanite-bearing quartzites of the southwestern part of the studied area, the Dn + 2 strike-slip microfaults are associated with N55 to N65 reverse faults. These faults suggest a main palaeostress σ1 N105, which can be correlated with those indicated by N100 tension gashes and N95 to N105 vertical joints.

5.3 The Dn + 3 and Dn + 4 strike-slip microfaults

Multidecakilometric fault planes represent the Dn + 3 and Dn + 4 fractures in the chaotic landscapes of the Atacora quartzites (Fig. 2). Criteria of stria superposition contribute to distinguish the Dn + 3 strike-slip microfaults as dextral N90 to N100 planes and sinistral N150 to N165 planes, indicating a major palaeostress σ1 N120 to N130 (Fig. 4C). The best illustration of this Dn + 3 compression can be observed in the Aleheride quartzitic hill. In fact, this hill corresponds to a hectometric Pn + 3 fold slightly overturned towards the northwest and with subhorizontal axis (N30–03NE). This fold is intersected by syn- to late-kinematic dextral (N95 to N105) and sinistral (N150 to N160) strike-slip microfaults. These conjugated microfaults suggest main subhorizontal palaeostresses σ1 N124 and σ3 N32, in perfect agreement with the fold orientation.

The Dn + 4 strike-slip microfaults are materialized by planes with uniform tectoglyphes, sinistral and submeridian (N170 to N190) or dextral and ESE–WNW to SE–NW (N110 to N130). This strike-slip microfault system resulted from a compression related to a major palaeostress σ1 generally N140 to N150 (Fig. 4D).

6 Synthesis and discussion

In northern Togo, the Dahomeyide Belt segment displays a dense network of brittle deformation features due to the Panafrican tectogenesis. At all scales, the distribution of lineaments and fractures reveals several brittle deformation episodes. A detailed analysis of successive strike-slip microfaults leads to determine the main palaeostress fields that built the Dahomeyide belt. Four successive post-collisional and subhorizontal compression episodes are defined and their specific directions are: (1) NE–SW to ENE–WSW, (2) ESE–WNW, (3) ESE–WNW to SE–NW and (4) SE–NW to SSE–NNW, respectively (Fig. 5). From the Dn + 1 episode until the Dn + 4 one, these palaeostress directions determine a progressive clockwise rotation of about 90°.

These different compression directions are materialized in the geometry of many structural elements recorded in northern Togo [34]. One should note that the Ln + 1 mineral or stretching lineations are not generally found in the direction of the minimal palaeostress σ3 determined for Dn + 1 phase. This is due to the reworking of the Sn + 1 foliation by later folding phases.

The Pn + 2 fold axes, in spite of their dispersal, are subparallel to the NNE-SSW orientation of the minimal palaeostress σ3 of Dn + 2 phase. Moreover, the mean axis (NE-SW) of the Pn + 3 folds is in agreement with the geometry of Dn + 3 compression. Finally, only the Dn + 4 compression can justify the NE–SW to ENE–WSW axial directions of the Pn + 4 virgations.

At the scale of the whole Trans-Saharan orogen, the Dn + 2 phase of northern Togo is comparable to the D3 phase defined in the Pharusian Branch and the Hoggar, where this D3 phase resulted in large submeridian mylonitic or shear zones [5,13,15,17]. The late fracturing, linked to the Dn + 4 compression, would be generalized to the whole orogen. Therefore, it is probable that the Wilson Cycle (divergence–convergence) evolution, in the case of the Trans-Saharan Belt, was controlled by the same Panafrican palaeotress fields [16,18,31]. However, it is not excluded that the geometry of the eastern border of the WAC could have influenced these palaeostress fields.

To explain the clockwise progressive rotation of the palaeostresses determined in northern Togo, one must replace the Trans-Saharan Belt in a much more regional frame, with an indentation system of Himalayan type that was the mainspring of Panafrican orogenesis in central and western Africa (Fig. 6). In fact, the device proposed by Ngako et al. [30] involves the East-Saharan Metacraton, serving as a punch point to the south or the SSW.

This results in the individualization of nappes, their thrusting on the northern border of the Congo–São Francisco craton, and their subsequent folding between 630 and 610 Ma. The punching between the Congolese craton and the Benino-Nigerian plate justifies the collision in the Dahomeyide Belt around 610 Ma [6,11,12]. Like European Hercynian and especially Himalayan Orogens [21,27,29], the indentation finally led, by accommodation, to a lateral eviction of material by a lithospheric transverse fault system [30]. This westward or northwestward material eviction would be the possible cause of the progressive clockwise rotation of palaeostresses, mainly during the last phases of the Dahomeyide belt structuring.

Let us note that brittle and ductile Phanerozoic deformations are known in many parts of Panafrican Trans-Saharan orogen: Late Hercynian deformation in the Sahara [26], Cretaceous brittle deformation in West Africa, related to the opening and evolution of the Atlantic Ocean and Benue trough [24], and Eocene compression in the West of the ‘Adrar des Iforas’ [26]. However, such deformations are not well defined in the Dahomeyide Belt, where Panafrican fractures underwent weak Phanerozoic reactivations [10,25,28,20]. Incompatible striae, resulting from these reactivations, are not used in the present study.