Version française abrégée

Introduction

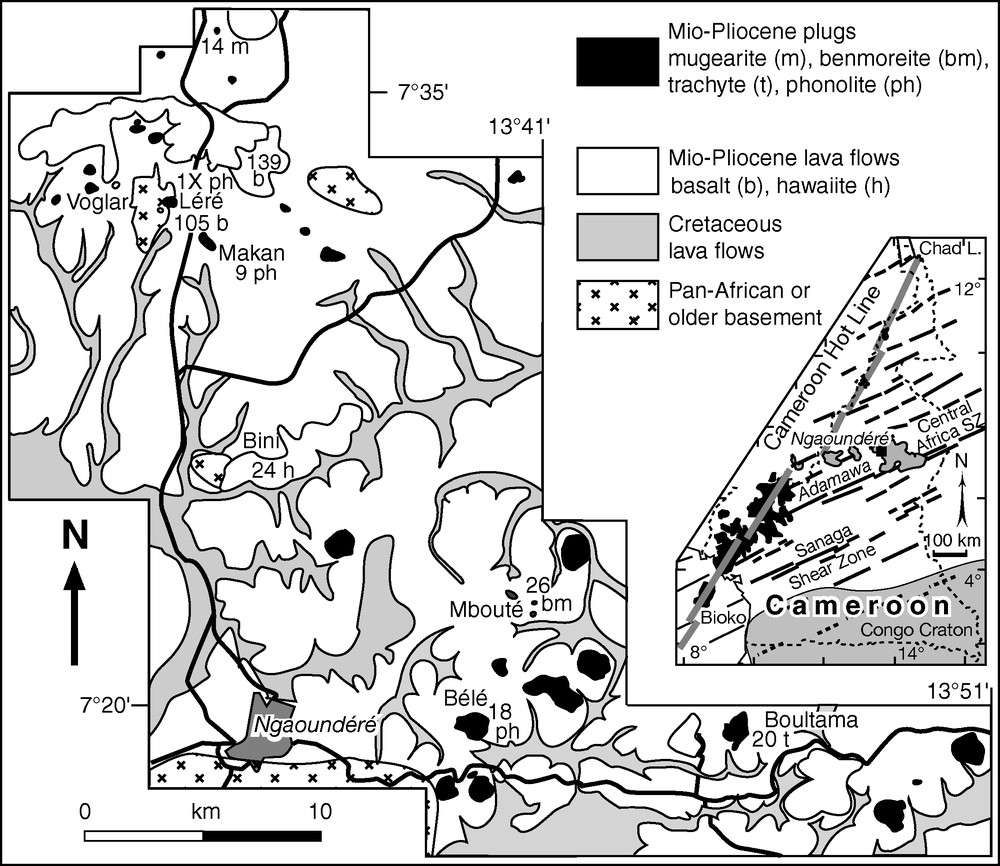

La zone étudiée couvre environ 400 km2 sur le plateau de l’Adamaoua, un horst orienté N70°E ([6], Fig. 1). La croûte continentale est peu épaisse (23 km [24]) et la lithosphère amincie (80 km [5]) sur un manteau asthénosphérique de faible densité [24]. Le socle est constitué de roches métamorphiques et de granitoïdes liés à l’orogénèse panafricaine ou antérieurs [20,27,28]. Il est partiellement couvert de laves basaltiques (coulées et rares necks), trachytiques et phonolitiques (35 necks). Un basalte a été daté (K–Ar) à 7,8 ± 1,4 Ma, et quatre laves felsiques entre 8,3 ± 0,5 et 10,9 ± 0,4 Ma, en conformité avec les données régionales [9,17]. Une série basaltique fortement latéritisée, d’âge Crétacé terminal [15], et une série basaltique récente (inférieur à 1 Ma [29]), avec cônes stromboliens et coulées associées (au sud de Ngaoundéré) sont aussi présentes sur le plateau de l’Adamaoua, où culminent deux stratovolcans alcalins miocènes : Tchabal Djinga [7] et Tchabal Nganha [21].

Geological sketch map of the Ngaoundéré area. Inset: the ‘Cameroon Hot Line’ (grey lines) and the Adamawa horst (after [4]).

Fig. 1. Carte géologique des zones nord et est de Ngaoundéré. En cartouche, l’Adamaoua et la « ligne chaude du Cameroun » (lignes grises) (d’après [4]).

Pétrographie et minéralogie

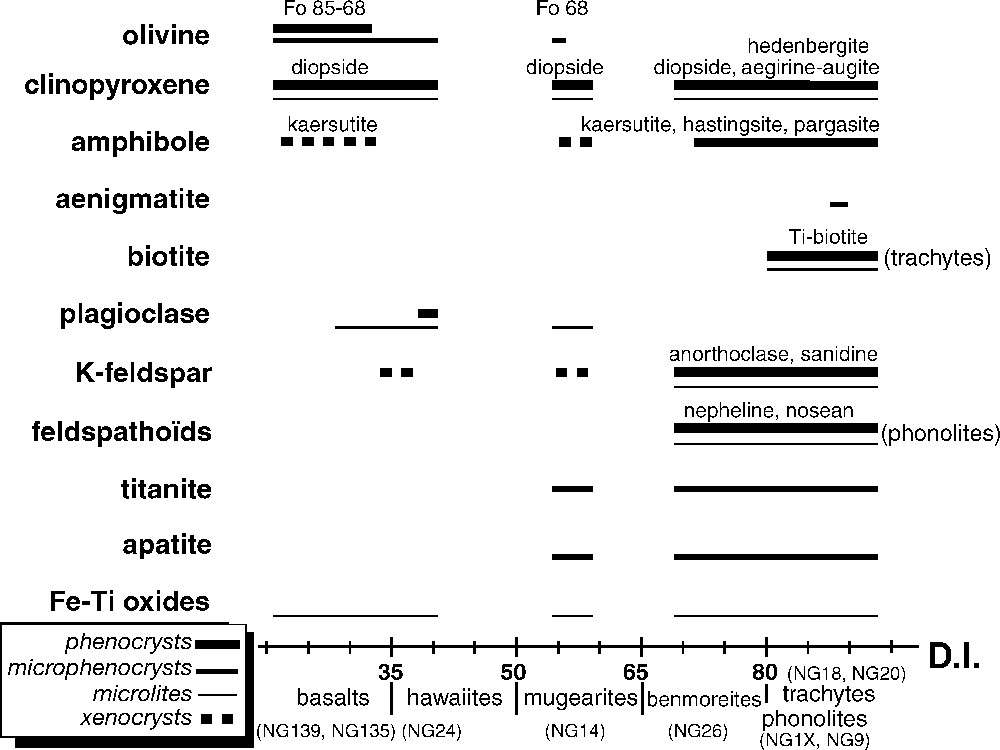

La nomenclature repose sur la valeur de l’indice de différenciation (I.D. [30]) et la distribution des phénocristaux pour les phonolites et trachytes (voir Fig. 2). Les laves basaltiques (basaltes, hawaiites) et intermédiaires (mugéarites) ont une texture microlitique porphyrique plus ou moins fluidale. Les xénocristaux arrondis (inférieurs à 4 mm) de kaersutite sont déstabilisés en diopside et Ti-magnétite. Les laves felsiques (benmoréites, trachytes, phonolites) ont une texture trachytique. Le pyroxène des benmoréites est un diopside alumineux. Les phonolites (I.D. > 78) contiennent des phénocristaux de diopside à bordure d’hedenbergite sodique et accessoirement d’aenigmatite. Les trachytes (I.D. > 80) sont à phénocristaux de diopside et de hornblende brune (kaersutite, Mg-hastingsite et Fe-pargasite). Les phonolites et trachytes hyperalcalins contiennent de l’augite aegyrinique et de l’aegyrine.

Distribution of minerals in the Ngaoundéré lava series according to the D.I. [30] of the host lavas.

Fig. 2. Distribution des phénocristaux, microphénocristaux, microlites et xénocristaux des laves de Ngaoundéré en fonction de l’indice de différenciation I.D. [30].

Le plagioclase des hawaiites a cristallisé entre 925 et 1025 °C et à 0,1 GPa [23]. L’évolution de la composition des clinopyroxènes (nomenclature : [18]) est continue, des benmoréites (diopside) aux phonolites et trachytes (augite aegyrinique, aegyrine), dans lesquelles les microlites sont riches en Na2O (13,0 %) et en TiO2 (6,0 %), témoignant d’une basse température (inférieure à 600 °C, [8]) et d’une faible

Géochimie

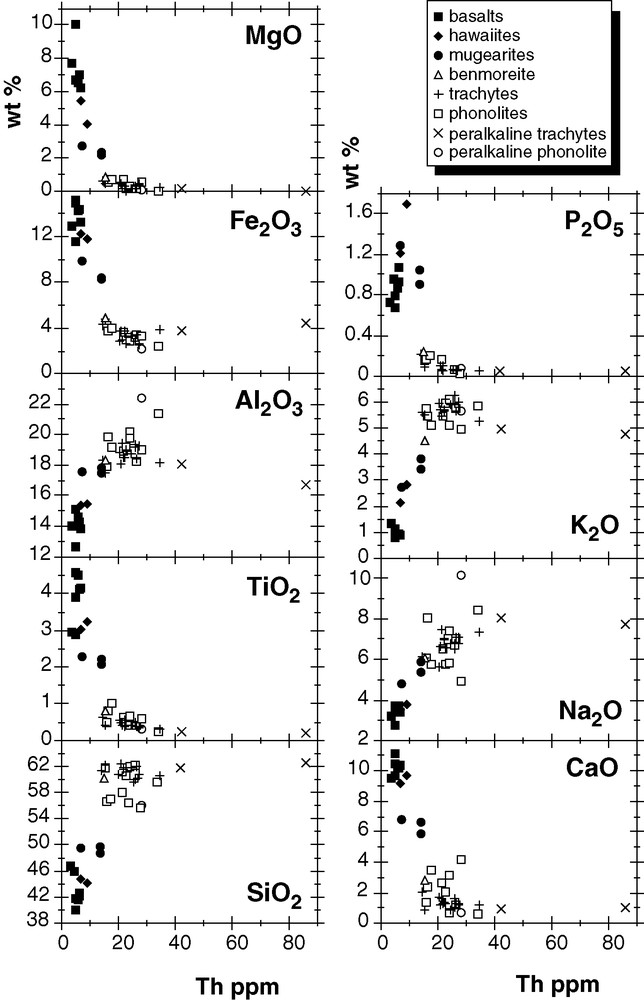

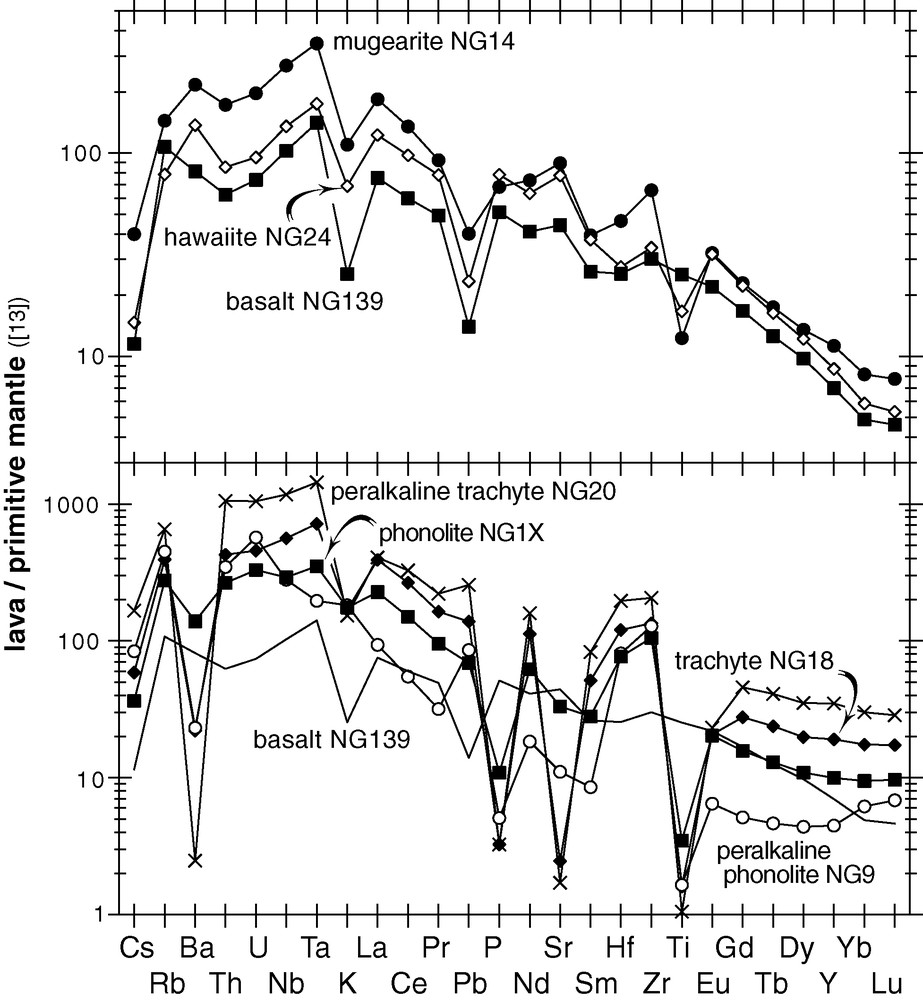

Les variations des teneurs en éléments majeurs et en traces sont représentées en fonction des teneurs en Th qui a été choisi comme indice de différenciation (Figs. 3 et 4). Dans un diagramme normalisé au manteau primitif, de fortes anomalies négatives en K et Pb caractérisent les basaltes (Fig. 5), et des anomalies négatives en Ba, P, Sr et Ti les laves felsiques. La phonolite hyperalcaline NG9 a un spectre de terres rares en forme de cuillère.

Major-element distribution diagrams vs. Th for the Ngaoundéré lavas.

Fig. 3. Diagrammes Th (ppm)–éléments majeurs (en% masse) pour les laves de Ngaoundéré.

Trace-element distribution diagrams vs. Th for the Ngaoundéré lavas.

Fig. 4. Diagrammes Th (ppm)–éléments en traces (ppm) pour les laves de Ngaoundéré.

Primitive mantle-normalized multi-element diagrams for the Ngaoundéré lavas; primitive mantle data after [13].

Fig. 5. Spectres multiéléments normalisés des laves de Ngaoundéré ; manteau primitif selon [13].

Les compositions isotopiques initiales (recalculées à 9 Ma) du Sr et du Nd des laves, 0,7031 < (87Sr/86Sr)i < 0,7041 et +5,0 >

Discussion et conclusions

Évolution de la série par cristallisation fractionnée

Les laves basaltiques et les laves felsiques appartiennent vraisemblablement à la même suite évolutive, malgré la présence d’un hiatus (Daly gap) entre 47 et 55 % de SiO2 (Fig. 3), comme en témoignent l’évolution progressive des compositions des phases minérales, les corrélations linéaires passant par l’origine (ou s’écartant peu de la linéarité) entre éléments incompatibles, la forte décroissance des teneurs en éléments de transition au cours de la différenciation (Figs. 3 et 4) et la modélisation du fractionnement des éléments majeurs (bilan de masse), avec des sommes des carrés des résidus, très faibles pour les laves basaltiques (inférieures à 0,07) et faibles pour les évolutions mugéarite–phonolite et trachyte–trachyte hyperalcalin (inférieures ou égales à 0,3). Le fractionnement de l’ensemble kaersutite + apatite + titanite + clinopyroxène + feldspath potassique a contribué à la forme en cuillère du spectre de terres rares de la phonolite hyperalcaline NG9, qui contient toutes ces phases (Fig. 5).

Mélanges magmatiques lors de la genèse des mugéarites

Les mugéarites (NG14) se situent dans le hiatus entre laves basaltiques et felsiques (Figs. 2 et 3 : Th–SiO2) et la présence simultanée de phases minérales typiques des laves basaltiques (olivine, plagioclase) et des laves felsiques (kaersutite, feldspath potassique, titanite, apatite), comme on l’a observé à Djinga [7], atteste des mélanges magmatiques lors de leur genèse.

Caractéristiques de la source et fusion partielle

Les faibles teneurs en Ni (124 ppm) et MgO (10,5 %) des basaltes révèlent le caractère évolué de magmas parents issus de la fusion partielle d’une source mantellique lherzolitique. Pour les basaltes alcalins, le déficit en Pb (Fig. 5) peut résulter de l’altération hydrothermale de la croûte océanique et/ou de sa déshydratation lors d’une subduction [3], et les anomalies positives en Nb et Ta [32] peuvent provenir d’un enrichissement mantellique lors d’une subduction. La subduction vers l’est, le long du craton congolais, durant l’orogenèse panafricaine, entre 800 et 630 Ma [20,31], a pu fertiliser le manteau et être à l’origine du caractère enrichi du magma parental des laves de Ngaoundéré. Cette hypothèse est confirmée par les données isotopiques Sr–Nd–Pb de ces laves, en particulier les rapports 206Pb/204Pb élevés (19,0–20,2). Une modélisation de la fusion partielle (valeurs des coefficients de partage selon [10]) a été réalisée : les basaltes de Ngaoundéré pourraient provenir de la fusion partielle (1 à 2 %) sous la lithosphère (profondeur supérieure à 80 km), dans le champ de stabilité du grenat, d’une source de type FOZO [25], de composition : manteau primitif [13]: 79 % + MORB altéré [14]: 20 % + sédiments pélagiques [14]: 1 %.

1 Geological setting

The Adamawa plateau is a N70°E horst bordered by the Djérem–Mbéré fault to the south and the Adamawa fault to the north. These faults belong to the Central Africa shear zone (CASZ). The CASZ, the Sanaga shear zone, and their extensions into the South-American continent (Patos, Pernambuco) before the opening of the South Atlantic Ocean are major shear zones in Cameroon [6] inherited from the Pan-African [20] or Eburnean orogenies [27]. These shear zones and their extensions crosscut both the continental crust and the upper mantle down to a depth of 190 km [5]. They belong to the numerous N70°E shear zone swarms of the central Atlantic ocean and central Africa that segment the ‘Cameroon Hot Line’ (CHL), the unique example on Earth of an active intraplate alkaline tectono-magmatic alignment simultaneously developed into both oceanic and continental domains [4]. The CHL is oriented N30°E and crosses the Gulf of Guinea and Cameroon on more than 2000 km, from Pagalu Island to Lake Chad (Fig. 1). The CHL is a geostructure distinct from the central Africa and Sanaga shear zones and from the Adamawa horst.

The studied area covers about 400 km2 on the Adamawa plateau. A large negative Bouguer gravity anomaly on the Adamawa plateau combined with seismic data suggests a thin (23 km) continental crust and a thin lithosphere (80 km) on an abnormally low-density asthenospheric mantle [5,24]. North of Ngaoundéré, the basement is composed of metamorphic rocks and granitoids related to the Pan-African orogeny (615 ± 27 to 652 ± 10 Ma) or older (880 ± 44 to 1008 ± 65 Ma) [28]. It is partially covered with basaltic lavas (flows and rare necks) and by thirty-five plugs of trachytes and phonolites, which are presently studied (Fig. 1). K–Ar dates have been obtained for one basalt (7.8 ± 1.4 Ma) and four felsic lavas (8.3 ± 0.5–10.9 ± 0.4 Ma), in agreement with regional data [9,17]. A highly lateritised basaltic series of Upper Cretaceous age [15], two alkaline stratovolcanoes of Miocene age (Tchabal Djinga [7] and Tchabal Nganha [21]) and recent basaltic Strombolian cones and associated lava flows (less than 1 Ma, [29]) south of Ngaoundéré are also exposed on the Adamawa plateau.

2 Petrography and mineralogy

The lava series includes basalts, hawaiites, mugearites, benmoreites, phonolites, and trachytes. Nomenclature is based upon the D.I. [30] and the phenocryst distribution (see Fig. 2). Basaltic (basalts: NG105, NG139; hawaiites: NG24) and intermediate (mugearites: NG14) lavas display a microlitic porphyritic texture. They contain kaersutite xenocrysts (less than 4 mm) that are often destabilized into diopside and Ti-magnetite. Al-rich diopside is present in benmoreites. The benmoreites (NG26) and phonolites (NG1X, NG9) commonly show trachytic flow or microlitic porphyritic textures. Diopside phenocrysts in phonolites are rimmed by a Na-hedenbergite ± aenigmatite corona. Aegyrine–augite and aegyrine may occur in peralkaline phonolites (NG9). Trachytes (NG18, NG20) have the classical trachytic texture.

Olivine (Fo85-Fo68), diopside, Ti-magnetite (47 < Usp% < 73) and ilmenite (37 < TiO2 wt.% < 50) in basalts are similar to the corresponding phases in the basalts from the CHL [4]. The clinopyroxene composition (nomenclature after [18]) of the felsic lavas ranges from diopside (benmoreites) to aegyrine–augite and aegyrine (phonolites and trachytes). The Na2O (13.0 wt.%) content of the aegyrine microlites in phonolites and trachytes is noteworthy. High TiO2 (6.0 wt.%) contents in aegyrine microlites indicate low crystallization temperatures (less than 600 °C, [8]) and low oxygen fugacity [19]. Kaersutite crystals equilibrated at 900–1050 °C at 0.42 GPa [22]. Mg-hastingsite (nomenclature after [16]) is rich in fluorine (4 wt.%) and crystallized under low oxygen fugacity in a late magmatic (subsolidus) stage [26]. Biotite is Ti-rich and crystallized at approximately 1000 °C [12]. The most calcic (An 62–38) plagioclases occur in basalts and hawaiites and crystallized at 925–1025 °C and 0.1 GPa [23]. In mugearites, the Ab content of the K-feldspar evolves progressively from Ab58 to Ab71. Benmoreites, phonolites and trachytes contain anorthoclase (Or50 to Or10). Nepheline crystallized below 700 °C, according to [11]. Nosean (3.1 Cl and 14.0 SO3 wt.%) contains numerous inclusions of pyrite. Apatite is rich in fluorine (3.5 wt.%) and LREE (La2O3: 0.7 and Ce2O3: 1.1 wt.%). Titanite is enriched in Zr (4200–17,000 ppm) and Nb (6500–13,500 ppm).

3 Geochemistry

Major- and trace-element contents are represented vs. Th content (used as differentiation index) (Figs. 3 and 4). MgO, Fe2O3, TiO2, CaO contents decrease, whereas SiO2, Al2O3, Na2O and K2O contents increase from basaltic to felsic lavas. P2O5 contents first increase from basalts to hawaiites, then strongly decrease to very low values in trachytes and phonolites. Transition element contents (Ni, Cr, V, Fig. 4) strongly decrease from basalts to felsic lavas. Rb contents increase from basalts (26 ppm) to peralkaline trachytes (350 ppm). Sr and Ba contents first strongly increase from basaltic lavas to mugearites, then strongly decrease in the felsic lavas. Zr (and Hf) contents increase regularly from basalts to trachytes and phonolites and Zr/Hf ratios are high (38 to 57); peralkaline trachyte NG20 has a very high Zr content (greater than 2000 ppm). Ta (and Nb) contents increase regularly for basaltic lavas, but the correlation is poorly defined for felsic lavas and some phonolites plot off the trend. La and Yb contents increase from basalts to peralkaline trachytes; however, some phonolites and trachytes do not plot on the correlation trend. Compared to other felsic lavas, peralkaline phonolite has a high Nb/Ta ratio (25; felsic lavas ≈ 13–15) and low MREE contents. In a primitive-mantle multi-element normalized diagram (Fig. 5), basalts display strong negative K and Pb anomalies.

The initial (recalculated at 9 Ma) Sr isotopic composition of most Ngaoundéré lavas (0.7031 < (87Sr/86Sr)I > 0.7041) is roughly comparable to that of the basalts of the oceanic and continental sectors of the ‘Cameroon Hot Line’ [4], whereas the initial Nd isotopic composition is slightly lower (+5.0 <

4 Discussion and conclusions

4.1 Differentiation of the lava series by crystal fractionation

Basaltic and felsic lavas are probably co-magmatic, despite a small compositional ‘Daly gap’ (47 < SiO2 wt.% < 55) observed between these two lava groups (Fig. 3). Mineralogical data (progressive evolution of mineral compositions with increasing differentiation) and geochemical data (regular and progressive major and trace element evolution) suggest that fractional crystallization had a major role in the differentiation of the Ngaoundéré lava series. Mass balance modelling for major elements gave results that are consistent with the distribution of mineralogical phases present as phenocrysts in the lavas. For example, basalt NG139 → hawaiite NG24 (ol: 5.1; cpx: 15.2; pl: 16.0; ox: 9.0; Σr2 = 0.01) → mugearite NG14 (ol: 1.4; cpx: 15.6; pl: 6.3; ox: 6.3; Σr2 = 0.07) → benmoreite NG26 (cpx: 8.3; K-felds: 12.0 ox: 0.8; Σr2 = 0.17) or → phonolite NG1X (cpx: 0.8; hb: 20.0; pl: 9.1; ox: 3.2; apatite: 2.7; Σr2 = 0.56) → peralkaline phonolite NG9 (K-felds: 39.0; ox: 12.0; titanite: 0.1; Σr2 = 0.06) and phonolite NG1X → trachyte NG18 (cpx: 8.0; K-felds: 6.0; ox: 1.0; haüyne: 8.0; Σr2 = 0.06) and trachyte NG18 → peralkaline trachyte NG20 (cpx: 1.0; K-felds: 10.0; ox: 0.2; Σr2 = 0.31). The least-square mass-balance values are low for basaltic lavas and acceptable for the evolutions to benmoreite NG9. The evolution in felsic lavas suggests that magma mixing and/or interaction with fluids were of minor importance during the magma differentiation. Fractional crystallization involving titanite is the most likely explanation for the increase of Nb/Ta ratio and the low MREE contents in peralkaline phonolite NG20. Fractionation of kaersutite + apatite + titanite + clinopyroxene + K-feldspar during the differentiation of felsic lavas (the peralkaline phonolite NG9 contains all these phases as phenocrysts or microphenocrysts) contributed to the spoon shape of their REE patterns and to the negative anomalies in Ti, P, Sr and Ba (Fig. 5) (Table 1).

Chemical analyses of representative lavas from Ngaoundéré area by ICP-AES (major elements) and ICP-MS (trace elements) at CRPG, Nancy, France. Analytical precision: see [2]; Sr, Nd and Pb isotope: mass spectrometry (VG Sector 54 TIMS), ‘université libre de Bruxelles’, Brussels, Belgium [1]

Tableau 1 Analyses chimiques (majeurs et traces) et compositions isotopiques Sr–Nd–Pb des laves représentatives des zones nord et est de Ngaoundéré. Les analyses ont été réalisées par ICP-AES (majeurs) et ICP-MS (traces), au CRPG, Nancy, France ; procédure analytique : voir [2]. Les rapports isotopiques du strontium, du néodyme et du plomb ont été déterminés par spectrométrie de masse (VG Sector 54 TIMS) à l’université libre de Bruxelles [1]

| Lava type | Basalt | Basalt | Hawaiite | Mugearite | Benmoreite | Phonolite | Peralkaline phonolite | Trachyte | Peralkaline trachyte |

| Sample nb | NG139 | NG105 | NG24 | NG14 | NG26 | NG1X | NG9 | NG18 | NG20 |

| SiO2 wt.% | 41.76 | 41.66 | 44.74 | 48.78 | 60.20 | 57.99 | 56.01 | 60.63 | 62.58 |

| TiO2 | 4.58 | 4.50 | 3.01 | 2.23 | 0.79 | 0.63 | 0.30 | 0.29 | 0.19 |

| Al2O3 | 14.00 | 14.59 | 15.39 | 17.51 | 18.35 | 18.90 | 22.43 | 18.19 | 16.75 |

| Fe2O3* | 14.94 | 14.23 | 12.20 | 8.40 | 4.85 | 3.59 | 2.13 | 3.86 | 4.43 |

| MnO | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.57 |

| MgO | 6.72 | 6.57 | 5.42 | 2.21 | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.03 |

| CaO | 10.41 | 10.20 | 9.17 | 6.60 | 2.85 | 2.68 | 0.72 | 1.17 | 1.02 |

| Na2O | 3.60 | 3.55 | 3.53 | 5.87 | 6.07 | 6.50 | 10.16 | 7.38 | 7.71 |

| K2O | 0.79 | 0.92 | 2.14 | 3.42 | 4.53 | 5.45 | 5.66 | 5.25 | 4.76 |

| P2O5 | 0.79 | 0.87 | 1.21 | 1.05 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

| I.L. | 1.31 | 1.78 | 2.44 | 3.01 | 1.26 | 2.07 | 1.39 | 1.62 | 1.48 |

| Sum | 99.12 | 99.07 | 99.45 | 99.31 | 100.25 | 98.97 | 99.14 | 99.08 | 99.57 |

| D.I. | 27.7 | 29.2 | 37.4 | 58.3 | 78.1 | 80.4 | 93.1 | 87.9 | 90.1 |

| Be (ppm) | 1.5 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 19.0 |

| Rb | 58 | 45 | 42 | 77 | 111 | 148 | 240 | 210 | 350 |

| Sr | 806 | 967 | 1413 | 1623 | 1140 | 604 | 201 | 45 | 31 |

| Cs | 0.31 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 1.07 | 1.01 | 0.98 | 2.25 | 1.57 | 4.45 |

| Ba | 493 | 564 | 830 | 1314 | 1834 | 840 | 140 | 133 | 15 |

| V | 318 | 319 | 163 | 95 | 7 | 17 | 11 | ||

| Cr | 86.4 | 25.5 | 41.0 | < D.L. | < D.L. | ||||

| Co | 47.9 | 43.1 | 30.3 | 11.5 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Ni | 45.8 | 23.6 | 50.9 | < D.L. | < D.L. | ||||

| Cu | 28 | 31 | 30 | 5 | 4 | < D.L. | < D.L. | ||

| Zn | 143 | 159 | 154 | 158 | 161 | 157 | 141 | 245 | 406 |

| Y | 27.5 | 32.1 | 34.3 | 44.4 | 39.7 | 39.2 | 17.6 | 75.1 | 137.5 |

| Zr | 293 | 435 | 333 | 638 | 748 | 1021 | 1244 | 1307 | 2004 |

| Nb | 63 | 87 | 84 | 166 | 175 | 180 | 172 | 347 | 725 |

| Hf | 6.8 | 9.3 | 7.4 | 12.4 | 14.4 | 20.5 | 21.7 | 32.1 | 52.4 |

| Ta | 4.95 | 5.86 | 6.14 | 12.16 | 11.93 | 12.33 | 6.88 | 25.16 | 50.51 |

| Th | 5.08 | 6.12 | 6.93 | 14.04 | 15.36 | 21.56 | 28.19 | 34.66 | 85.86 |

| U | 1.50 | 1.77 | 1.93 | 4.00 | 4.13 | 6.70 | 11.57 | 9.27 | 21.29 |

| Pb | 2.4 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 7.0 | 11.3 | 12.1 | 15.0 | 24.2 | 44.9 |

| La | 46.3 | 53.1 | 75.4 | 113.0 | 128.9 | 139.5 | 57.4 | 239.7 | 249.8 |

| Ce | 96 | 115 | 157 | 216 | 240 | 240 | 88 | 426 | 524 |

| Pr | 11.9 | 12.8 | 18.9 | 22.3 | 23.9 | 23.0 | 7.7 | 39.6 | 53.5 |

| Nd | 49 | 56 | 75 | 87 | 89 | 74 | 22 | 133 | 189 |

| Sm | 10.1 | 11.4 | 14.5 | 15.3 | 13.9 | 10.9 | 3.3 | 19.8 | 32.1 |

| Eu | 3.20 | 3.56 | 4.63 | 4.70 | 4.23 | 2.96 | 0.94 | 3.01 | 3.38 |

| Gd | 8.60 | 9.67 | 11.40 | 11.76 | 10.20 | 8.07 | 2.63 | 14.20 | 23.49 |

| Tb | 1.18 | 1.31 | 1.54 | 1.64 | 1.43 | 1.22 | 0.44 | 2.24 | 3.85 |

| Dy | 6.22 | 6.88 | 7.78 | 8.63 | 7.67 | 6.95 | 2.79 | 12.64 | 22.37 |

| Ho | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.30 | 1.53 | 1.37 | 1.30 | 0.58 | 2.44 | 4.29 |

| Er | 2.55 | 2.91 | 3.19 | 3.90 | 3.71 | 3.77 | 1.85 | 7.02 | 12.29 |

| Tm | 0.33 | 0.37 | 0.40 | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.33 | 1.07 | 1.89 |

| Yb | 2.03 | 2.29 | 2.43 | 3.38 | 3.54 | 3.93 | 2.56 | 7.24 | 12.46 |

| Lu | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.55 | 0.62 | 0.44 | 1.10 | 1.82 |

| (87Sr/86Sr)9Ma | 0.70312 | 0.70331 | 0.70400 | 0.70317 | 0.70434 | 0.70685 | |||

|

|

+5.03 | +4.39 | +2.20 | +3.80 | +2.16 | +2.38 | |||

| 206Pb/204Pb | 19.976 | 19.985 | 19.502 | 20.235 | 19.038 | 19.296 | |||

| 207Pb/204Pb | 15.686 | 15.706 | 15.681 | 15.726 | 15.686 | 15.695 | |||

| 208Pb/204Pb | 39.563 | 39.777 | 39.700 | 39.805 | 39.011 | 39.423 |

4.2 Evidence of magma mixing for mugearites

Mugearites (∼49 ± 1 wt.% SiO2; i.e. NG14) plot inside the gap between basaltic and felsic magmas. Magma mixing between these two magmas is attested by the occurrence of mineral phases characteristic of both basaltic (olivine, plagioclase) and felsic (kaersutite, K-feldspar, titanite, apatite) lava groups. Similar mugearites from Djinga have been interpreted [7] as products of mixing between basaltic and trachytic magmas.

4.3 Characteristics of the source and partial melting

Rather low Ni (124 ppm) and MgO (10.5 wt.%) contents attest to the evolved character of the parental magmas generated by partial melting of a lherzolitic mantle source. Negative K and Pb anomalies (Fig. 5) have been interpreted as resulting either from hydrothermal alteration of oceanic crust or from dehydration at great depth (∼110 km) during subduction [3]. The Nb and Ta positive anomalies presumably result from the enrichment of these elements in the mantle source during subduction [32]. Subduction towards the east along the Congo craton (northern Cameroon–southeastern Chad) occurred between 800 and 630 Ma [20,31] during the Pan-African orogeny or earlier [28], and could have fertilized the mantle, generating a FOZO-type reservoir as sources of the Ngaoundéré parental magma. This hypothesis is confirmed by Sr–Nd–Pb isotope data of lavas from Ngaoundéré, in particular the high (19.0–20.2) 206Pb/204Pb ratios. Modelling points out that the magmas from which the Ngaoundéré basalts are issued could result from 2% partial melting (partition coefficients after [10]) of a FOZO-type [25] source composed of 79% primitive mantle [13] +20% altered MORB [14] +1% pelagic sediments [14]. Melting should have taken place below the lithosphere, at great depth (>80 km) in the garnet stability field.

Acknowledgements

The French ‘ministère de la Coopération’ is acknowledged for providing a grant to O.N. for a nine-month stay in France in the ‘Laboratoire de magmatologie et de géochimie inorganique et expérimentale, université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie’, Paris, and to B.D. for financial support to field work in Cameroon. Stay of B.D. in Ngaoundéré has been substantially supported by the University of Ngaoundéré. The isotopic measurements at Brussels (ULB) were financially supported by FNRS grants to D.D. This article is contribution IPGP No. 2283.