1 Introduction

The existence of saliferous structures as well as the timing of halokinetic movements has been the subject of numerous controversies in Tunisia. Many surface studies consider central Tunisia's mountains as anticlines and reject the existence of salt domes and diapirs in this area. Moreover, different authors have suggested several epochs (Jurassic, Aptian, and Upper Cretaceous) as the beginning of salt movements based on surface [11,15,17,23] and subsurface [4,5,12,18,30] data. The seismic expression of such complex salt structures can be difficult to interpret, with perhaps little or no signal of the salt body level. However, it is precisely in these complex geological environments that the gravity and magnetic fields can be better tested and are most meaningful. The bodies with no signal on the seismic lines can be interpreted as anticlines, overthrust strata, volcanic intrusions, faults, mud mounds… The gravity method measures density lateral changes. Similarly, the magnetic method measures lateral changes in magnetic mineral content. Bouguer and susceptibility anomalies along with the velocity analysis and the seismic interpretation allowed us to identify the nature of these structures and define their geometry.

In this study, we intend to analyze subsurface structuring and complex salt features in central Tunisia from the west (Souinia) to the east (Mezzouna) across the Majoura and Kharrouba domains by integrating potential field methods (gravity–magnetic) and seismic reflection data. We further propose to deduce the geodynamic implication during Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous extension periods.

2 Geological setting

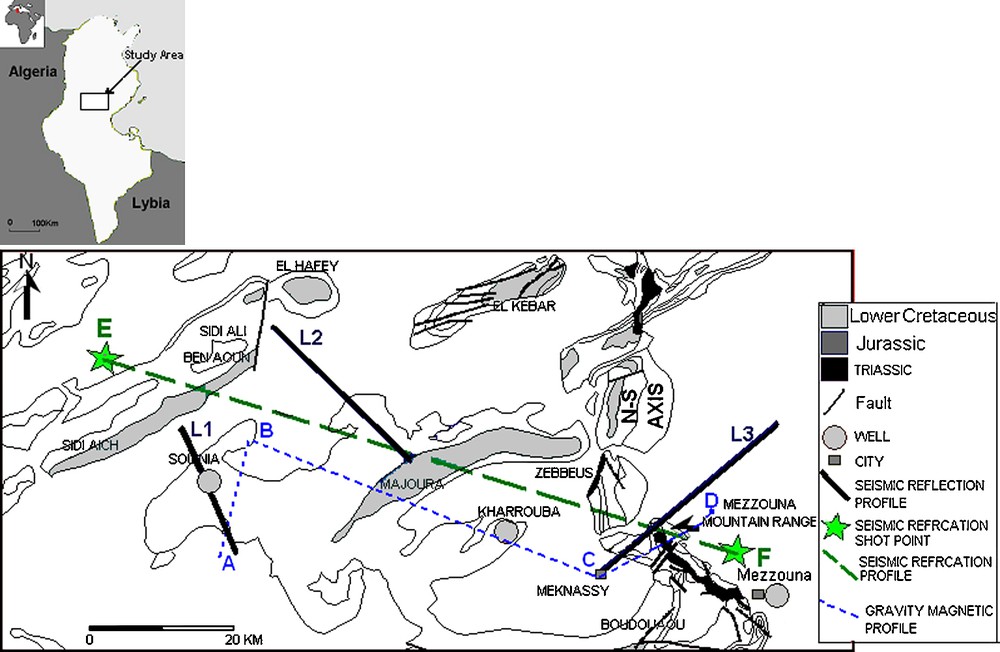

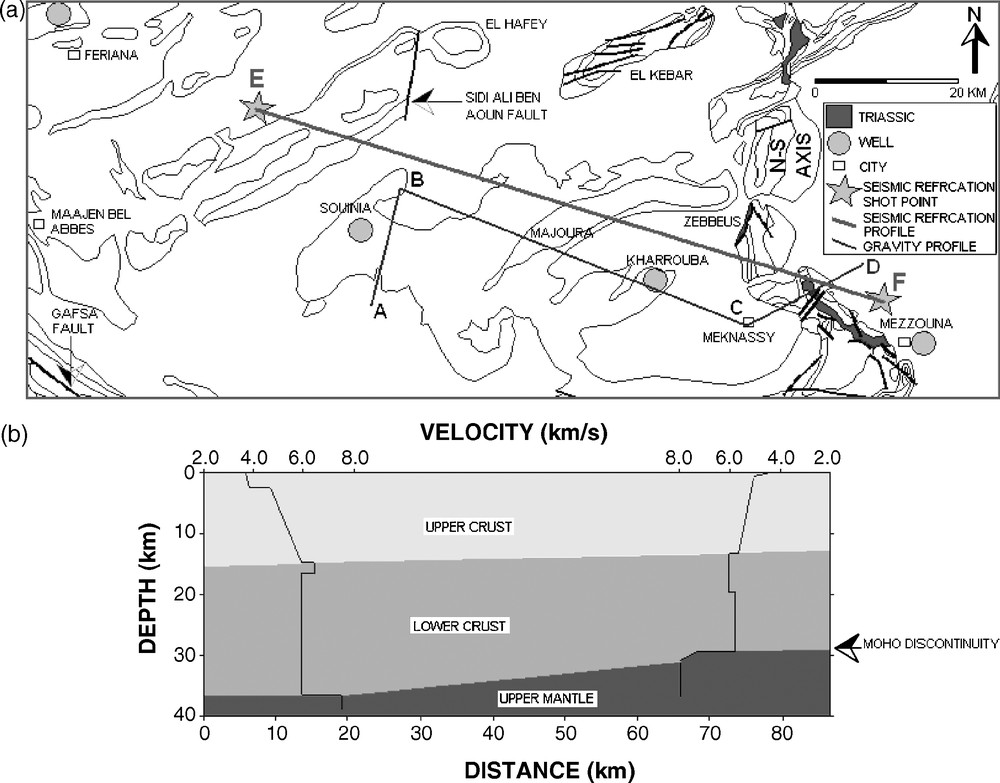

The study area is located in the central Atlas of Tunisia (Fig. 1) and is characterized by NE–SW to east–west-trending anticlines (Fig. 1). Lower Cretaceous sediments outcrop as anticline cores of Sidi Aïch, Sidi Ali Ben Aoun, El Hafey, Majoura-Meloussi, Kebar, Boudouaou mountains, and in the North–South Axis. However, the Jurassic deposits only outcrop along the North–South Axis [1,14,24,25]. The particular NW–SE-oriented structure of the Mezzouna Mountain range shows neither Lower Cretaceous nor Jurassic deposits [9,10,19] (Fig. 1). These mountains present abnormal outcropping Triassic deposits that follow NW–SE faults [9,10]. In this structure, the Campanian–Maastrichtian Abiod Formation directly overlies the Upper Triassic salt. Indeed, unconformities and lack of some stratigraphic levels have been noticed [9,19].

Study area location map and used seismic lines.

Fig. 1. Carte de localisation du secteur d’étude et de la maille sismique utilisée.

From the Late Triassic to the Early Aptian, the Tunisian margin seems to be characterized by submeridian and east–west extensional periods [1,5,7,8,17,28,33]. This extension reactivated reghmatic deep faults mainly oriented NE–SW, WNW–ESE and north–south [1].

Subsurface studies in this region demonstrated NE–SW, NW–SE, east–west, and north–south deep-seated flower faults, interpreted as strike-slip faults that have been reactivated since the Upper Triassic–Lower Jurassic rifting [4,18,30]. These faults bound different tectonic blocks of the region and are often associated with Triassic salt pillows and domes that are responsible for high-zone and syncline basin structuring [3–6,27,30,31].

3 Seismic analysis

The area of interest is well covered by 2D seismic lines from the Gafsa–Sidi Bouzid Permit, acquired by the AGIP (Tunisia) LTD in 1982 and 1983. However, these seismic profiles have average quality and some of them are not migrated, so care must be taken in interpreting them. Previous studies that used and analyzed these data [3–6,18,30] indicated probable salt dome existence. A recent study took interest in the geometry evolution of the salt bodies from west to east in this region.

Reflection seismic lines across the main structures of the study area have been analyzed. Seismic and sequence stratigraphic analysis, petroleum well control and surface data studies in the central Atlas of Tunisia led us to identify and to calibrate Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous horizons. We selected three migrated seismic sections crossing the main structures in this area: L1, L2, and L3.

The L1 seismic section is oriented NW–SE across the Souinia structure. It shows asymmetric anticline with large curve range affected by a flower fault system, which is associated with chaotic reflectors in the deep and apparent detachment level of the Upper Triassic (Figs. 2 and 3). The chaotic seismic facies is interpreted as Upper Triassic evaporite levels mobilized by deep faults. This movement began at least since the Lower or the Middle Jurassic [27]; it expressed itself through pinching out and onlapping into the salt pillow flank (Fig. 4). Below this structure, the correspondent iso-stacking velocity section shows a pull-up velocity anomaly that we associate with the high velocity of Triassic ascendant evaporites (Fig. 5). This configuration has been described in the Shib Mountain deep structure, situated in the southern part of this area [32].

L1 seismic section showing the Souinia well above a salt pillow.

Fig. 2. Ligne sismique L1, montrant le puits de Souinia à l’aplomb d’un coussin de sel.

Detailed portion of the L1 section, showing the detachment level in the Upper Triassic salt.

Fig. 3. Portion détaillée de la section sismique L1 montrant le niveau de décollement dans le salifère du Trias supérieur.

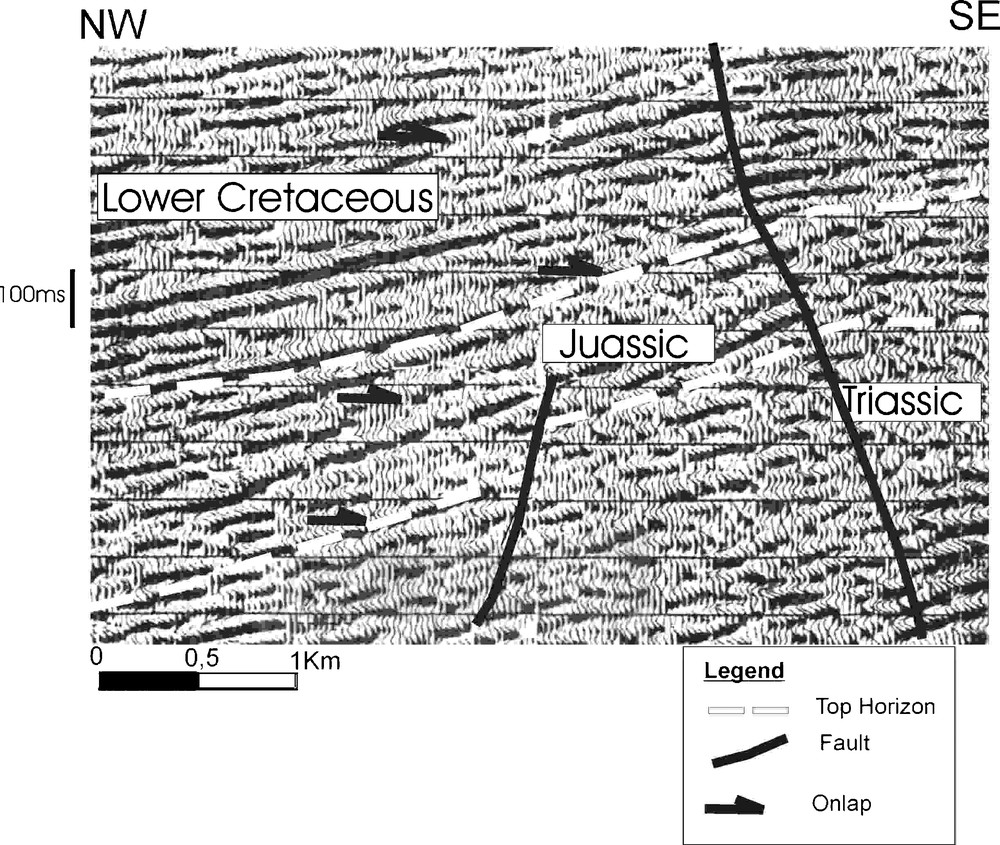

Detailed seismic section, showing pinching-out and onlapping on the dome flank.

Fig. 4. Portion détaillée d’une section sismique, montrant le biseautage et les configurations en onlap sur le flanc du dôme.

L1 iso-stacking velocity section, showing a pull-up anomaly below the Souinia structure.

Fig. 5. Section d’isovitesse de sommation de la ligne sismique L1, montrant une anomalie en pull up associée à la structure de Souinia.

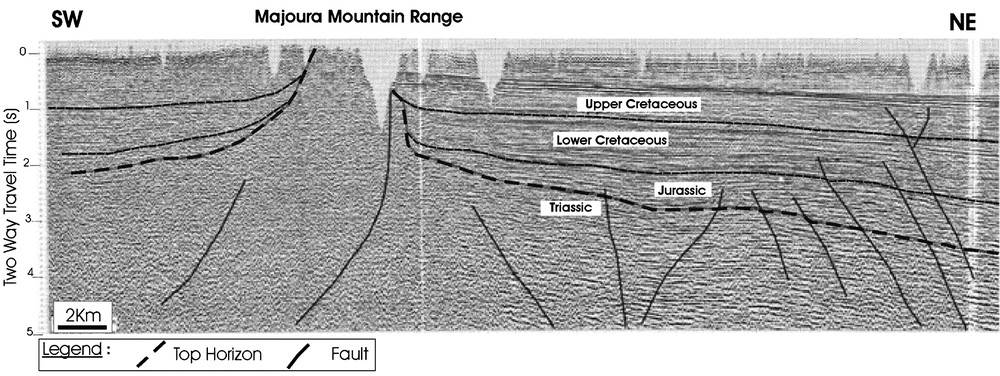

The seismic line L2, trending NW–SE, between the Majoura and El Hafey structures, (Fig. 1) shows a basin structuring as a rim-syncline depocenter to the northwest of the Majoura structure and a high platform zone extending towards the Jebel Majoura and Meloussi outcrops. The section shows chaotic seismic facies under platform highs. This facies has been interpreted as a Triassic upward-narrowing salt dome limited by major deep-seated faults (Fig. 6). These faults have a sub-vertical structure that becomes listric in the deeper horizons. The Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous seismic sequences show lateral thicknesses and seismic facies variations from the Majoura rim syncline (Fig. 6) towards the Majoura–Meloussi platform [3,27]. These sequences are bounded by eustatic and tectonic sedimentary unconformities, which are expressed by aggradational and retrogradational onlap, toplap configurations and erosional truncations [3,4,6,27,30]. Below the gutter, the Upper Triassic deposit's thickness is reduced. Thus, we can relate all this to the salt creep that was carried out towards the fault corridors since the Jurassic rifting and has continued during the Lower Cretaceous extension period.

L2 seismic line, showing the Majoura Dome and the subsequent rim-syncline.

Fig. 6. Ligne sismique L2, montrant le dôme de Majoura et la gouttière synclinale associée.

The seismic line L3, oriented SW–NE across the Mezzouna area, shows a large chaotic reflector to the southwest, interpreted as ascendant evaporitic material under the Mezzouna Mountain range. Towards this structure, we noticed variations in the thickness of Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous sequences between subsiding and high blocks with aggrading and retrograding onlap and pinching-out horizons towards the high block border (Fig. 7). This has been interpreted as consequent to salt movements during these periods. The high block in Mezzouna is seen as a horst bordered by deep faults that probably facilitated salt creep and intrusion, inducing diapir formation.

L3 seismic line across the Mezzouna mountain range, showing Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous thickness reduction towards the salt wall.

Fig. 7. Section sismique L3 passant par la chaîne de Mezzouna, montrant la réduction de l’épaisseur des séries du Jurassique et du Crétacé inférieur en allant vers la ride salifère.

These analyses and studies of seismic data across the whole area show differentiated structuring into highs and depocenter blocks limited by deep-seated NE–SW, north–south, east–west, and NW–SE faults interpreted as intruded by Upper Triassic salt. The early salt migration seems to have started with the platform fracturing during the Lower Liassic rifting event [27]. The salt migration is also attested to by Middle Jurassic, Upper Jurassic, and Neocomian space depocenter migrations [3,4,6,26,27,30].

4 Potential gravity and magnetic analysis

The analysis of seismic reflection profiles in central Tunisia, from the Souinia to the Majoura–El Hafey and Mezzouna zones, shows a hazy expression of complex geology. We interpret it as salt bodies, even though many geologists are still sceptical about these interpretations and about the existence of dome in this area. In such a case, the lateral changes in density (gravity method) and in magnetic mineral content (magnetic method) are of special interest, since they provide valuable information to complete and to strengthen the seismic data interpretation. Gravity and magnetic data (Fig. 9) were analyzed along an east–west profile, crossing the North–South Axis to add insights into:

- 1) the deep structural architecture characterizing central Tunisia;

- 2) the complex salt features.

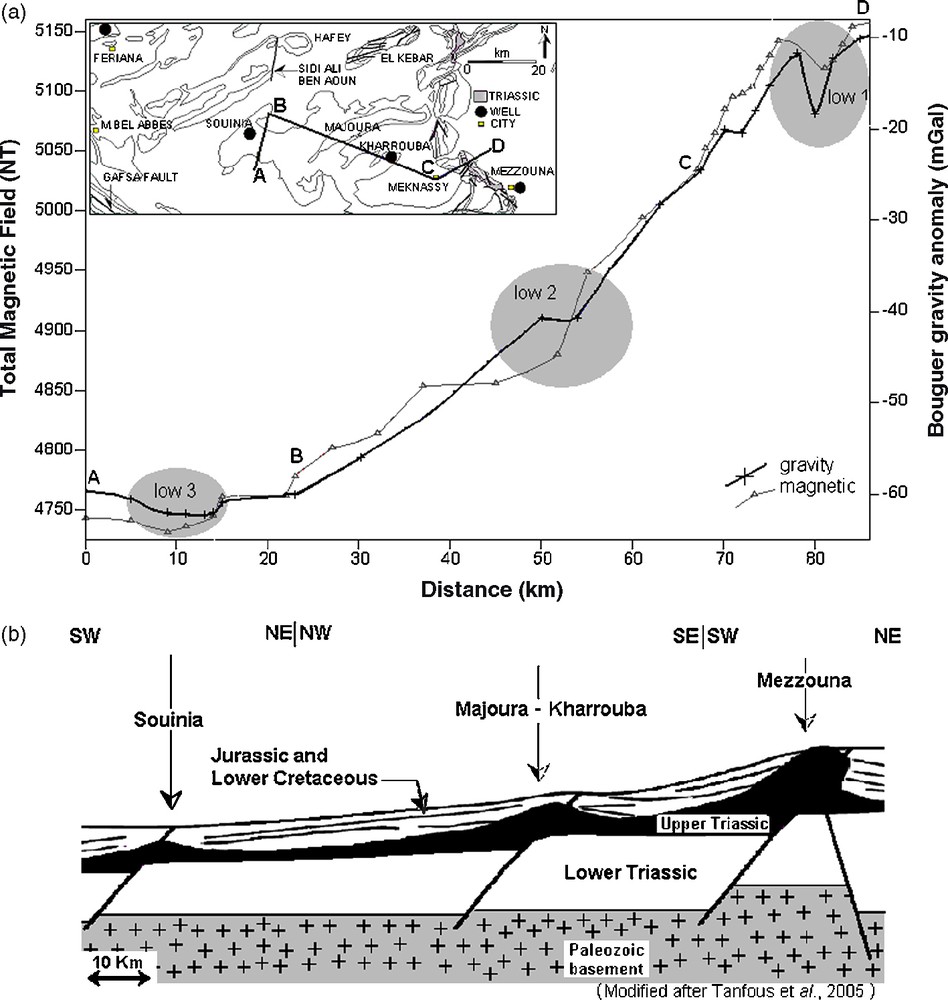

(a) Bouger gravity anomaly and total magnetic field profiles across the Souinia, Majoura–Kharrouba, and Mezzouna areas. (b) Corresponding model, showing the evolution, from the west to the east, to salt pillow, then salt dome, and salt wall.

Fig. 9. (a) Variations de l’anomalie gravimétrique de Bouguer et du champ magnétique total à travers les structures de Souinia, Majoura–Kharrouba et Mezzouna. (b) Modèle correspondant, montrant une évolution, d’ouest en est, vers des structures en coussin de sel, dôme de sel et ride salifère.

Gravity data, tied to the 1971 International Gravity Standardization Net [22], were merged and reduced using the 1967 International Gravity formula. Free-air and Bouguer gravity corrections were made using sea level as data and 2.67 g cm−3 as a reduction density. On the Bouguer gravity and magnetic profile covering central Tunisia, we can notice a regional variation from the east to the west. This variation represents the regional gravity field that is determined from crustal thickness variations [13] (Fig. 8). Fig. 8 illustrates a refraction seismic profile elaborated [16] after the seismic refraction data of Geotraverse EGT’85 [13]. This profile shows a crustal thickness reduction from the northwest to the southeast. The Moho depth in this region varies from the Atlasic basin to the Sahel domain. This explains the regional gravity anomaly and the total magnetic field variation in this direction (Fig. 9a).

Refraction seismic profile (EF, drawn by Gabtni [16], based on Geotraverse shooting points [13]), showing a crust thickness reduction from the northwest to the southeast.

Fig. 8. Profil de sismique réfraction EF (dessiné par Gabtni, 2006 [16], en se basant sur les données des points de tir de Geotraverse [13]), montrant un amincissement crustal en allant du nord-ouest vers le sud-est.

However, other anomalies that come off the Moho effect are noticeable in Fig. 9a.

The shape and amplitude of the residual gravity and magnetic variations are represented by some anomalies resulting from basement shape and its sedimentary cover variations (Fig. 9a) [13]. Three anomalies (1, 2 and 3) have specifically been noticed. Moderately low-gravity anomalies 2 and 3 confirm that in the Souinia and Majoura-Kharrouba zones, the Triassic salt movement reaches salt pillow and salt dome stages without piercing the cover, whereas the important low-gravity and magnetic anomaly 1 in the Mezzouna area proves that the Triassic salt that outcrops in this structure is implanted as salt diapir that pierced its cover. According to the seismic analyses, this must have occurred during the Upper Cretaceous and Cenozoic compression periods.

5 Conclusion

Reflection seismic sections as well as gravity and magnetic profiles interpreted in the Souinia, Majoura–Kharrouba, and Mezzouna areas (central Tunisia) confirm the existence of buried Triassic salt bodies characterized by chaotic reflection, high-velocity propagation and negative gravity, and magnetic anomalies.

Aggrading and retrograding onlaps and pinching-out of the Jurassic and the Lower Cretaceous horizons towards these structure borders illustrate the halokinetic movements of these bodies during these periods.

The Triassic salt intrusion reached stages of salt pillow and salt dome in the Souinia and the Majoura–Kharrouba, whereas in the Mezzouna mountain range, it had pierced its cover during the Upper Cretaceous and Tertiary, reaching a more advanced stage as a salt diapir marked by important gravity and magnetic anomalies.

In this study area, the Liassic rift faulting has induced a tilted block structuring of the initial Jurassic platform [27]. This is associated with the posterior compression tectonic phases and the sedimentary loading that induced Triassic salt creep and halokinetic movements and moulded the geometry of the salt diapir along the normal faults. Such phenomena have been described in the Algerian Sahara Atlas [2,29] in the Portuguese margin [21], and in the Alps [20].